Hong Kong Apostasy

This is the latest chapter in ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’, a feature of ‘The Best China’ section of China Heritage that is devoted to the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill Protest Movement. Its author, the veteran journalist Lee Yee 李怡 (李秉堯), was the founding editor of The Seventies Monthly 七十年代月刊 and he has been a prominent commentator on Chinese, Hong Kong and Taiwan politics, as well as the global scene, for over half a century.

This essay is translated from ‘Ways of the World’ 世道人生, a column that Lee Yee writes for Apple Daily 蘋果日報.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

31 July 2019

***

Note:

- Explications added by the translator are generally marked by square brackets [].

***

Other Essays by Lee Yee on the 2019 Hong Kong Protests:

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Endgame Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 5 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Young Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 16 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Hong Kong Goes Grey for a Day’, China Heritage, 20 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘This is Who We Are — We Are Hong Kong’, China Heritage, 22 July 2019

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Hong Kong Cannot Lose’, Apple Daily, 26 July 2019 (in Chinese)

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Living and Learning in Hong Kong 2019’, China Heritage, 29 July 2019

See also:

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Playing by Peking’s Rules’, Asian Wall Street Journal, 11-12 July 1986

***

Back in the Year

當年

Lee Yee 李怡

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

At the end of my essay the other day, I wrote:

‘if, in the past, we had had the courage that Young Hong Kong has today, we would not be in the present predicament.’

— [Lee Yee, ‘Living and Learning

in Hong Kong 2019’, 29 July 2019]

Perhaps I should say a few words about exactly what I meant by ‘in the past’ [當年, or ‘back in the year’]? More to the point, what was it about that era that meant we did not demonstrate the kind of courage evinced by Young Hong Kong today?

前天拙文末段說:「如果當年我們有現在年輕人這樣的勇氣,香港不會變成這樣。」也許需要回顧一下,「當年」是指甚麼時候?那時是怎樣的社會氣候使我們沒有現在年輕人的勇氣?

When writing he words ‘back in the year’ I was thinking of the year 1984 — it is probably no coincidence that this also happens to be the title of George Orwell’s famous dystopian novel Nineteen Eight-Four. It was in that year, on 20 April 1984 to be precise, that Geoffrey Howe, the British Foreign Secretary, formally announced that the United Kingdom would cede suzerainty over Hong Kong in 1997.

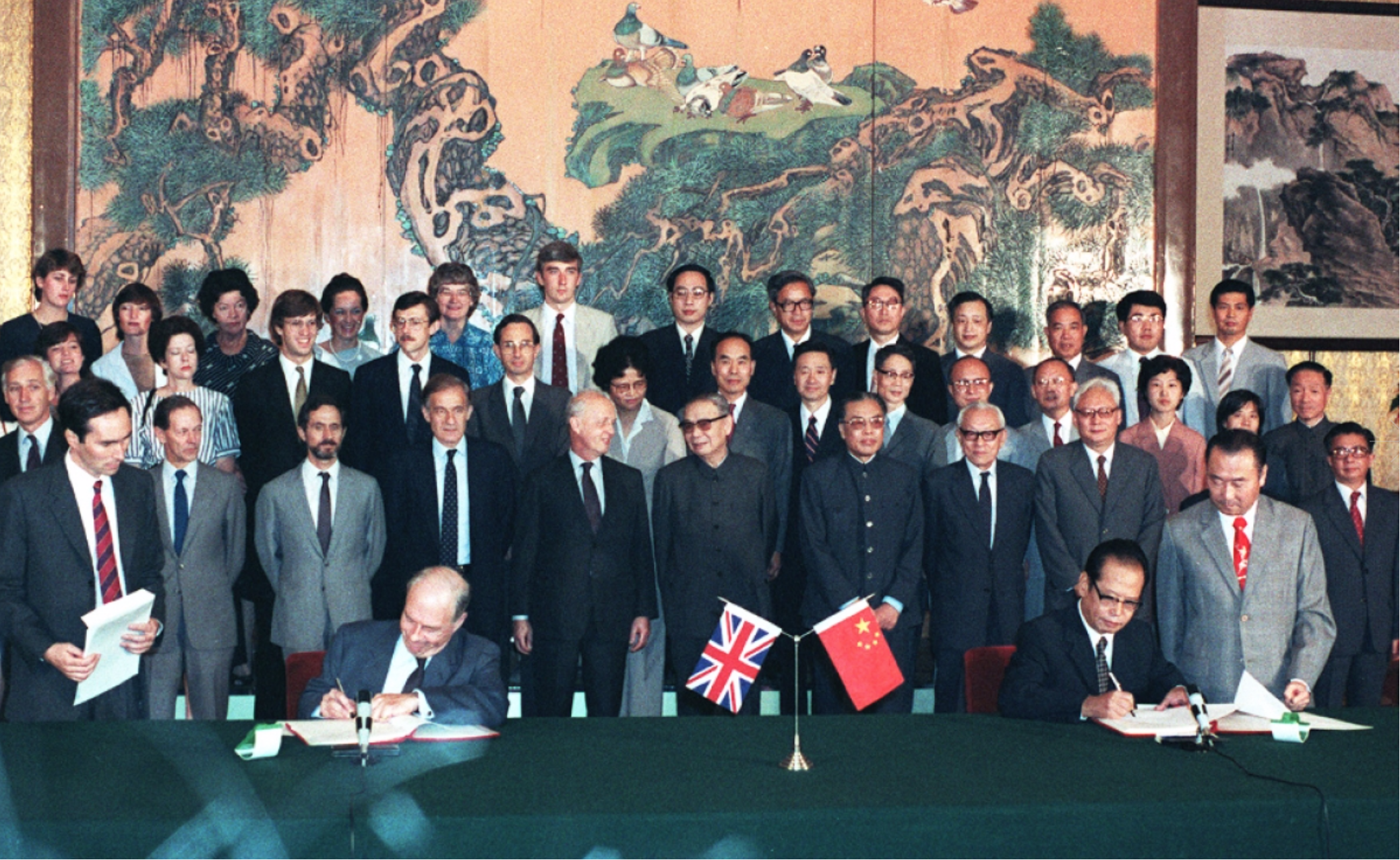

To be even more precise, ‘back in the year’ is about those five months between Howe’s 20 April announcement and the 26th of September that same year. On that later date, the People’s Republic of China and the United Kingdom initialled the draft agreement of the Sino-British Joint Declaration [which was the product of two years of negotiation].

[Note: In Hong Kong on 20 April Sir Geoffrey Howe made a statement on the approach of Her Majesty’s Government to the negotiations. He said that it would not be realistic to think of an agreement that provided for continued British administration in Hong Kong after 1997: for that reason Her Majesty’s Government had been examining with the Chinese Government how it might be possible to arrive at arrangements that would secure for Hong Kong, after 1997, a high degree of autonomy under Chinese sovereignty, and that would preserve the way of life in Hong Kong, together with the essentials of the present system. He made it clear that Her Majesty’s Government were working for a framework of arrangements that would provide for the maintenance of Hong Kong’s flourishing and dynamic society, and an agreement in which such arrangements would be formally set out.

— from the White Paper ‘A Draft Agreement between

the Government of the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Northern Ireland and

the Government of the People’s Republic of China

on the Future of Hong Kong’, 26 September 1984]

我指的當年,是1984(奧威爾以這個年份為小說名是巧合嗎?)。那一年的4月20日,英國外相賀維在香港宣佈放棄1997年以後對香港的主權與治權。從這一刻,到同年9月26日,中英雙方草簽《中英聯合聲明》,這幾個月就是我所指的「當年」。

If, during those five months, the people of Hong Kong had reacted en masse to the negotiations about the territory’s future in a manner similar to the Anti-Extradition Bill Protests of today, and had they thereby attracted a corresponding level of international attention, the British may well have felt obliged to reconsider their approach to ceding control. Even then, they it is highly unlikely that they would have changed course entirely, surely such an outpouring would at least have pressured them to raise the stakes in the negotiations with Beijing.

For example, they could have argued a case favouring the implementing political democracy prior to the 1997 handover; they also could have pressed for the establishment of an effective mechanism of international oversight that could monitor the status of Hong Kong’s political autonomy after 1997.

Back in the year, however, people in Hong Kong just did not evince any substantive opposition to the way in which the British were selling out their long-term interests without consultation.

如果在那幾個月裏,香港有現在反送中那樣大規模的民意反彈,引起像現在那樣廣泛的國際關注,很難說英國在香港民眾和國際壓力下不會重新檢視放棄香港的立場,即使不改變,至少也會提高對中國的要價,比如達致在97前就在香港實現完全民主的機制,以及設定更有效的對97後香港自治的國際監督。但那時的香港人並沒有展現這樣強的反對英國出賣香港人的意志。

It goes without saying that this lack of awareness among average people had a great deal to do with the fact that Hong Kong did not have a democratic system; but you can’t entirely blame the British for this. That, however, is a topic for another day.

這當然也跟香港一直以來缺乏民主有關,但香港沒有發展民主,並不能完全怪英國。對這問題,我日後再詳述。

Having never enjoyed the benefits of democracy, Hong Kong people had not evolved any substantive sense of political autonomy nor, in relation to that deficiency, had they developed a particularly strong sense of belonging. For this crucial reason — the lack of democracy and all that pertains to it — that Sze-yuen Chung [appointed by the British as] the Senior Member of the Hong Kong Executive Council ended up shuttling impotently between Beijing and London in a strenuous lobbying effort on behalf of Hong Kong people. Neither side ever accorded his views any particular weight. As he remarked when I later interviewed him, Chung simply did not have the wherewithal to oppose effectively the various proposals that were being advanced either by the British or by the Chinese side. Or, as he put it to me, ‘I had no real standing; it’s because I wasn’t appointed democratically’.

[Note: For more on Sze-yuan Chung in this context, see 李怡, ‘昔人已乘黃鶴去’,《蘋果日報》, 2018年11月16日]

Indeed, at the time, there were no legitimate representatives of Hong Kong popular opinion at the negotiating table; furthermore, throughout the negotiations the Chinese side was adamant in its refusal to countenance Hong Kong people having any say in the matter. They rejected out of hand all suggestions that the discussions should be a ‘three-legged stool’, that is, three-way negotiations.

[Note: The Hong Kong Chinese-language media at the time decried the situation as being akin to ‘盲婚啞嫁’ — an arranged marriage in which the bride has no say over arrangements made by patriarchs.]

由於從來沒有民主,因此絕大部份香港人並沒有作主精神,和由此產生的對香港的歸屬感;由於沒有民主,因此當時即使有行政局首席議員鍾士元這樣的人為香港人的權益奔走於倫敦與北京,卻不被中英雙方重視,他在跟我的訪談中表示,他不能和中英對抗,因為「我沒有後盾,沒有選民」。香港那時確實沒有民意授權的代表,而中共在與英國談判香港前途問題時,也堅決否定香港人應有一個角色,即否定所謂「三腳凳」。

Most Hong Kong people came to this place to escape tyranny on the Mainland.

[Note: ‘to escape tyranny on the Mainland’ is our transition of 避秦, literally, ‘to flee the Qin’. In his depiction of an idyllic world of peace and contentment, the fourth-century writer Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 said that people had come to the Peach Blossom Spring 桃花源 ‘to flee the Qin’, that is, they sought (and found) a refuge from the harsh rule of the Qin dynasty and its infamous First Emperor 秦始皇, a figure to whom Mao Zedong compared himself.]

Many just wanted a place where they could enjoy the ‘Freedom From Fear’. Over time, the British system with its traditions and protections instilled in Hong Kong people a belief that freedom and the rule of law were a natural state of affairs, something that was theirs to enjoy without them having to exert any particular effort. They had grown so accustomed to this environment that it seemed as natural as breathing the air around us; they did not give it a second thought. It simply was; it was a given; it wasn’t something for which you had to fight.

Back in the year 1984, although the majority of Hong Kong people opposed to the territory being handed over to the People’s Republic — something reflected in the media at the time — there was no widespread support for organised protest. In fact, there were hardly any demonstrations against what was going on at all, let alone any violent resistance.

香港人大部份是從大陸避秦而來。許多人到香港也只是求有一個免於恐懼的地方,由於英國帶來的法治傳統,使香港人覺得自由與法治是毋須付代價而自然得到的,因此也就如同呼吸空氣那樣不覺得珍貴,也不覺得需要抗爭才會得到。當年儘管反對把香港交給中國的市民佔絕大多數,輿論也如此顯示,但社會卻缺乏為此抗爭的意識。連示威遊行都缺缺,遑論勇武啦。

Added to all of that was the political situation in China.

Back in the year 1984, the Mainland was still recovering from the disastrous Cultural Revolution and Beijing had launched policies in favour of economic openness and systematic reform. Superficially at least, the party-state was being run by an enlightened faction led by Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang and Premier Zhao Ziyang. Although the majority of Hong Kong people shared a generally negative view of the Communists, at the time things seemed to be moving in a positive direction and that gave them reason to be cautiously optimistic about the future.

另外就中國局勢而言,當年正從文革的災難走出來,開始實行改革開放路線,在枱面上主政的是開明派的胡耀邦和趙紫陽。儘管香港多數人對中共的印象不佳,但對當時的大陸局面仍然抱一點希望。

There were, of course, other factors also at play, including the activities of the advocates of Hong Kong democracy. These people argued that, following the end of British colonial rule and under the umbrella of Chinese national sovereignty, the people of Hong Kong would finally be able to rule themselves independently.

At the time, Premier Zhao Ziyang even responded to questions about this posed by Hong Kong university students by declaring in writing that:

‘It is self-evident that Hong Kong will be run democratically’.

Back in the year, many students at tertiary institutions were lulled into a state of quiescence by all of this; they were complacent and they believed that once Hong Kong ‘returned’ to China true democracy could be realised.

當然,還有另一個因素,就是香港那時有一些民主回歸派,認為在擺脫英國殖民地統治之後,可以在中國主權下實現真正的港人民主治港。總理趙紫陽也以「民主治港,理所當然」來回覆港大學生會。當年的大專學生,有不少是在這種民主幻覺中接受回歸的。

That’s why — back in the year 1984 — it was simply impossible for there to be what I described earlier as ‘the courage that Young Hong Kong has today’.

And, back in the year, just like now, I was involved in the media, as well as being a writer. When the Sino-British negotiations started in the early 1980s the magazine I edited — The Nineties Monthly — had already severed itself from the Leftists Camp. In 1979 [when the Governor of Hong Kong, Murray MacLehose, made his first official visit to the People’s Republic and raised the question of Hong Kong’s sovereignty with Deng Xiaoping], right up to 1984, and then during the lead up to 1997, both in my work as an editor and as a writer, I consistently expressed my opposition to the Mainland takeover and my support for democratisation in Hong Kong.

In my view, once under Chinese sovereignty Hong Kong had scant hope of enjoying any meaningful kind of democratisation. But I was only a magazine editor, and a writer. All I could do — and did do — was to make my opinions heard. I was not a social activist; nor did I have the wherewithal to have any major impact on the situation.

因此,「現在年輕人這樣的勇氣」在當時的環境下不可能存在。我當時以至現在,都是一個傳媒人,一個寫作者。在香港前途談判開始時,我主編的雜誌已經脫離左派陣營。從1979年九七問題出現,到1984,到1997,我一直反對回歸,支持民主。我認為在中國主權之下,實現民主的機會極渺茫。但我只是編雜誌,只是為文,只是發聲,沒有涉足社運,也沒有能力左右大局。

Nonetheless, I have no regrets about the views I expressed and have maintained since leaving the Leftist Camp [in 1981], and I certainly do not think that they have been nugatory.

儘管如此,我對自己脫離左派以來的寫作沒有後悔,也不會妄自菲薄。

Back in the year, however, people like me were creatures with but limited understanding. In particular, we didn’t appreciate the importance of resistance; we should have openly fought against the looming threat of authoritarianism.

Over the past two months, people like me have learned many things from Young Hong Kong. In the struggle for the future of this place, although we might not be able to protect the young from the onslaughts they are enduring, at least we should not cast brickbats as they stand on the front line.

但由於當年的歷史處境,帶給我們的認識局限,這種局限主要就是對專制強權缺乏抵死抗爭的意識,這兩個月來,我們從年輕人身上學到很多。為了香港的未來,我們即使不能站在年輕人身旁遮風擋雨,至少不要在他們身後丟石頭。

***

Source:

- 李怡, ‘當年’, 《蘋果日報》, 2019年7月31日