The Tower of Reading

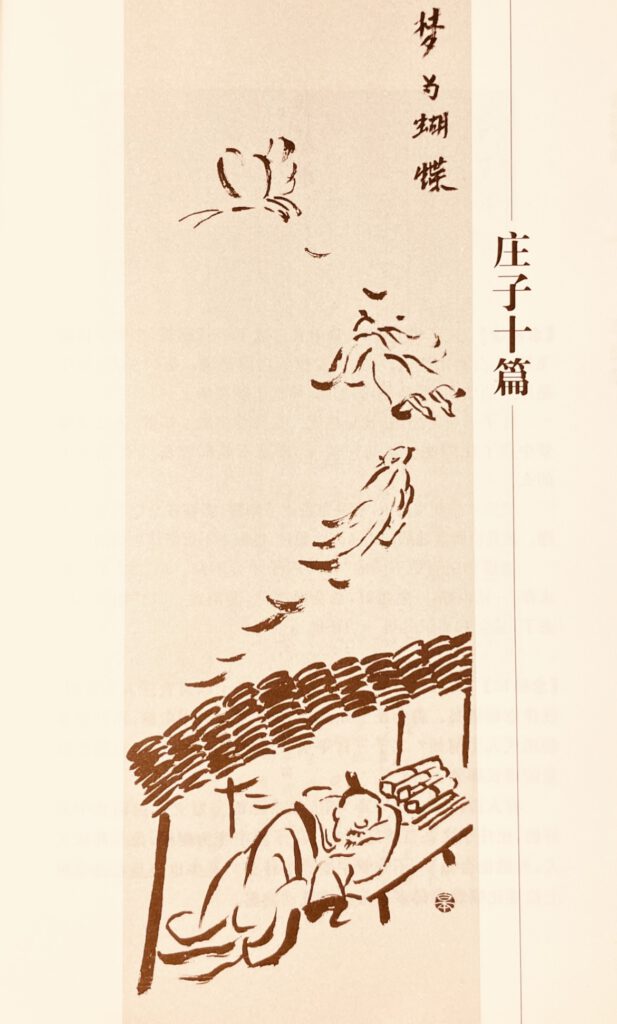

夢為蝴蝶

This is the first of ten chapters devoted to Zhuangzi in Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts by Zhong Shuhe 鐘叔河著《念樓學短·莊子十篇·篇首》。The title of Zhong’s selections from Zhuangzi 莊子, one of most entrancing works in the Chinese tradition, is ‘Butterfly Dreaming’ 夢為蝴蝶。

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

Preface

The Tower of Reading is a China Heritage series focussed on the work of Zhong Shuhe (鐘叔河, 1931-), one of the most influential editors and publishers in post-Mao China and a writer celebrated in his own right both as a prose stylist and as an interpreter of classical Chinese texts.

The full title of the series — ‘Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with The Master of The Tower of Reading’ — is our translation of 念樓學短 niàn lóu xué duǎn, the enticingly lapidary name under which Zhong Shuhe published over five hundred newspaper columns over three decades (see 念樓學短2002年 and 念樓學短2020年).

Each selection features a short text of under 100 characters which Zhong translated into modern Chinese. To these Zhong appended ‘A Comment from the Master of the Tower of Reading’ 念樓曰 niàn lóu yuē, ‘casual essays’ — 小品文 xiǎopǐnwén or 雜文 záwén, modern terms for such works, akin to the traditional terms 筆記 bǐ jì, ‘jottings’ or 劄記 zhá jì, ‘miscellaneous literary notes’ — that expanded on the theme of the chosen text, or a particular historical figure or a particular incident.

For more on the background to this project, see Introducing The Tower of Reading.

***

The seventh section of Studying Short Classical Texts with The Master of the Tower of Reading consists of ten selections from Zhuangzi 莊子. We introduce this material with two observations about Zhuangzi, the historical figure and the book, by the translators Burton Watson (1925-2017) and A.C. Graham (1917-1991). We take a detour by reprinting a comment that Graham made on the butterfly dream (his Inner Chapters of Zhuangzi 莊子·內篇 remains essential reading) which is followed by two English-language versions of the text and a pointed short essay by Zhong Shuhe. We conclude with Zhuangzi’s butterfly reimagined by Xi Xi, the celebrated Hong Kong writer.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

14 February 2024

***

Note:

Hanyu Pinyin is used for the romanisation of Chinese names, words and terms, including in quoted material.

***

Further Reading:

- 鍾叔河著, 《念樓學短》,長沙:岳麓書社,2020年

- Burton Watson, Early Chinese Literature, New York: Columbia University Press, 1962

- A.C. Graham, Chuang-tzu: The Inner Chapters, London/ Boston: Allen & Unwin, 1981

- Xi Xi, The Teddy Bear Chronicles, New York, Columbia University Press, 2021

On Zhuangzi

The Zhuangzi, a work in thirty-three chapters, was said to have been written by Zhuang Zhou [莊周], a philosopher whose dates are tentatively given as 369-256 BC. The Zhuangzi is unique in early Chinese literature for two reasons. One is that it is the only prose work of the ancient period which does not, at least in part, deal with questions of politics and statecraft. Zhuangzi has little advice for the rulers of his time…. He is concerned only with the life and freedom of the individual. Freedom is the central theme of the work — not political, social, or economic freedom, but spiritual freedom, freedom of the mind…

The second thing which makes the Zhuangzi unique is the remarkable wit and imagination with which this philosophy is expounded. Other works of Chinese history and philosophy abound in anecdotes that are obviously based on no more than myth or legend, but are always put forward in a solemn, pseudo-historical manner. The Zhuangzi, on the contrary, deals in deliberate and unabashed fantasy… . Nowhere else in early Chinese literature do we encounter such a wealth of satire, allegory, and poetic fancy. No single work of any other school of thought can approach the Zhuangzi for sheer literary brilliance.

— Burton Watson, Early Chinese Literature, 1962, p.160

***

We know very little about the life of Zhuang Zhou (commonly called Zhuangzi), who wrote the nucleus of what Arthur Waley described as ‘one of the most entertaining as well as one of the profoundest books in the world.’ The book is the longest of the classics of Taoism, the philosophy which expresses the side of Chinese civilisation which is spontaneous, intuitive, private, unconventional, the rival of Confucianism, which represents the moralistic, the official, the respectable. The Historical Records of Sima Qian (c. 145 -c. 89 BC), in a brief biographical note, date Zhuangzi in the reigns of King Hui of Liang or Wei (370-319 BC) and King Xuan of Qi (319-301 BC). They say that he came from the district of Meng in the present province of Henan, and held a minor post there in Qiyuan (‘Lacquer Garden’, perhaps an actual grove of lacquer trees) which he abandoned for private life. For further information we have only the stories in the book which carries his name, a collection of writings of the fourth, third and second centuries BC of which at least the seven Inner chapters [內篇] are generally recognised as his work.

Whether we take the stories about Zhuangzi as history or as legend, they define him very distinctly as an individual. In this he is unique among Taoist heroes, of whom even Laozi, the supposed founder of the school, never in anecdote displays any features but those of the Taoist ideal of a sage.

Most of the tales about Zhuangzi fall into three types: we find him mocking logic (always in debate with the sophist Hui Shi), or scorning office and wealth, or ecstatically contemplating death as part of the universal process of nature. Only the second of these themes belongs to conventional Taoist story-telling, and even here he strikes a distinctive note, at once humorous and deep. Whatever the historical worth of the stories, in reading the Inner chapters one has the impression of meeting the same very unusual man. It is not simply that he is a remarkable thinker and writer; … he gives that slightly hair-raising sensation of the man so much himself that, rather than rebelling against conventional modes of thinking, he seems free of them by birthright. In the landscape which he shows us, things somehow do not have the relative importance which we are accustomed to assign to them. It is as though he finds in animals and trees as much significance as in people; within the human sphere, beggars, cripples and freaks are seen quite without pity and with as much interest and respect as princes and sages, and death with the same equanimity as life. This sense of a truly original vision is not diminished by familiarity with other ancient Chinese literature, even that in which his influence is deepest. …

The more closely one reads the disconnected stories and fragmentary jottings in the Inner chapters, the more aware one becomes of the intricacy of its texture of contrasting yet reconciled strands, irreverent humour and awe at the mystery and holiness of everything, intuitiveness and subtle, elliptical flights of intellect, human warmth and inhuman impersonality, folkiness and sophistication, fantastic unworldly raptures and down-to-earth observation, a vitality at its highest intensity in the rhythms of the language which celebrates death, an effortless mastery of words and a contempt for the inadequacy of words, an invulnerable confidence and a bottomless scepticism. One can read him primarily as a literary artist, as Confucians have done in China. However, one cannot get far in exploring his sensibility as a writer without finding one’s bearings in his philosophy.

— A.C. Graham, Chuang-tzu: The Inner Chapters, 1981, pp.3-4

***

Butterfly Dreaming

two translations

Chapter One in Section Seven of

Studying Short Classical Chinese Texts with

The Master of The Tower of Reading

念樓學短

夢為蝴蝶

Version One:

Once Zhuang Zhou dreamt he was a butterfly, a butterfly flitting and fluttering around, happy with himself and doing as he pleased. He didn’t know he was Zhuang Zhou. Suddenly he woke up and there he was, solid and unmistakable Zhuang Zhou. But he didn’t know if he was Zhuang Zhou who had dreamt he was a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming he was Zhuang Zhou. Between Zhuang Zhou and a butterfly there must be some distinction! This is called the Transformation of Things.

Version Two:

Last night Zhuang Zhou dreamed he was a butterfly, spirits soaring he was a butterfly (is it that in showing what he was he suited his own fancy?), and did not know about Zhou. When all of a sudden he awoke, he was Zhou with all his wits about him. He does not know whether he is Zhou who dreams he is a butterfly or a butterfly who dreams he is Zhou. Between Zhou and the butterfly there was necessarily a dividing; just this is what is meant by the transformations of things.

夢為蝴蝶

昔者,莊周夢為蝴蝶,栩栩然蝴蝶也。自喻適志與,不知周也。俄然覺,則蘧蘧然周也。不知周之夢為蝴蝶與。 蝴蝶之夢為周與,周與蝴蝶。則必有分矣。此之謂物化。

—《莊子·齊物論》

***

The Dreaming Argument

We cannot name the undifferentiated, since names all serve to distinguish, and even to call it ‘Way’ reduces it to the path which it reveals to us. However, since that path is what one seeks in it, the ‘Way’ is the most apposite makeshift term for it. According to the Outer chapters, the term ‘Way’ is ‘borrowed in order to walk it’. Laozi sometimes calls it the ‘nameless’, and also says ‘I do not know its name, I style it the “Way”‘. As for Being and Reality, the existential verbs in Classical Chinese are you [有], ‘there is’, and wu [無], ‘there is not’, nominalisable as ‘what there is/something’ and ‘what there is not/nothing’; the words used for pronouncing something real or illusory are shi [實], ‘solid/full’, and xu [虛], ‘tenuous/empty’. Only differentiated things may be called ‘something’ or ‘solid’; as for the Way, it may be loosely described as ‘nothing’ or ‘tenuous’, but in the last resort it transcends these with all other dichotomies, since the whole out of which things have not yet divided will be both ‘without anything’ and ‘without nothing’. In so far as we can coordinate the Chinese concepts with our own, it seems that the physical world has more being and reality than the Way. However it is only by grasping the Way that we mirror the physical world clearly, and our illusory picture of a multiple world is compared with a dream from which the sage awakens. The famous story of Zhuangzi’s dream of being a butterfly seems, however, to make a different point, that the distinction between waking and dreaming is another false dichotomy. If I distinguish them, how can I tell whether I am now dreaming or awake?

— A.C. Graham, Chuang-tzu: The Inner Chapters, pp.21-22

[Note: See also Descartes’ Dreaming Argument.]

A Comment from The Tower of Reading:

Zhuangzi was the first to describe death as ‘the transformation of things’ [物化]. Zhuangzi investigates the big questions of life through parables and anecdotes. The style is audacious and full of bravado. No computers were involved, so how does his wisdom stand up in this day and age? Is the only standard by which we can judge the evolution of writing that of sheer quantity? Is the bloating and proliferation of the way people have come to express themselves over the last 2,300 years [since the time of Zhuangzi] really a sign of progress?

Some claim that modern vernacular Chinese is superior to the literary language of the past. Those who make this claim naturally think they are the most outstanding writers of the vernacular. It goes without saying, therefore, that they must regard themselves as being far superior to Zhuangzi.

Zhuang Zhou only dreamed of being a butterfly. You wonder what the elite writers of today turn into in their dreams? Whatever it is daresay occupies a far superior branch of the evolutionary tree than a butterfly — some species of mammal perhaps?

— Zhong Shuhe, translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Original Chinese Text

學其短:The selected Classical Chinese text, with notes;

念樓讀:Zhong Shuhe’s translation into Modern Chinese; and,

念樓曰:Zhong Shuhe’s comment.

我是誰

夢為蝴蝶 《莊子》

昔者,莊周夢為蝴蝶,栩栩然蝴蝶也。自喻適志與,不知周也。俄然覺,則蘧蘧然周也。不知周之夢為蝴蝶與。 蝴蝶之夢為周與,周與蝴蝶。則必有分矣。此之謂物化。

【學其短】

•本文錄自 《莊子·齊物論》。《莊子》三十三篇,分內篇、外篇和雜篇,篇下再分章(本書統一稱篇)。

•蝴:通「胡」。

•莊子,名周,戰國時宋國蒙地(今河南商丘)人。

•昔:可通「夕」。

•喻:通「愉」。

• 本文中的前三個「與」字均通「歟」。

【念樓讀】 莊子晚上做夢,夢中自己成了一隻蝴蝶,在空中翩翩飛舞,十分自由快樂,一點也沒想到莊周是誰。霎時夢醒,卻還是原來的莊周,手是手,腳是腳,伸直了躺在床上。

莊子於是乎想道:我是誰呢? 是我夢中成了蝴蝶,還是蝴蝶中成了莊周呢?這兩種情況,難道不是同樣都有可能發生的麼?

我剛才感到很快樂,是因為我成了蝴蝶,能夠在空中自由地飛翔。這是兩腳落地的莊周從未體驗過,也根本不可能體驗到的。

蝴蝶和莊周是不同的「物」,感受才會不同。但「物」不可能永存,一覺也好,一生也好,總會要變化,要消亡。「物」如果「化」去了,感覺和意識等等一切還能不變嗎?

【念楼曰】 稱死亡日物化,自莊子始。莊子以寓言述人生哲理,汪洋怒肆極矣。嘗謂子如能復活,肯定不會用電腦,而其智慧較現代人為何如?二千三百年來文章的進化,難道只表現在數量的增長膨脹上麼?

有人說白話文比文言文好,他自己的文章叉是白話文中最好的,比莊子之文自然好得多。莊子夢中變為蝴蝶,他是高級文人,當然也會做夢,不知夢中變成了什麼?至少也該是在進化樹上位置比蝴蝶高得多的某種哺乳動物罷。

***

Source:

- 鍾叔河著, 《念樓學短》,上冊,長沙:岳麓書社,2020年,第126-127頁。

***

Xi Xi’s Zhuangzi

Xi Xi 西西 was the pen name of Cheung Yin (張彥, 1937-2022), an acclaimed Hong Kong writer. Her work is a delicate admix of the naïve and the absurd. Regarded as a pioneer of experimental filmmaking and screenwriting in the 1960s, Xi Xi went on to publish two collections of poetry, seven novels, twenty-one short story and essay collections and one stand-alone novella. Her essays also frequently appeared in the popular press, as did her translations.

In 1989, Xi Xi was diagnosed with breast cancer. Post-operative treatment damaged the nerves in her right hand, but she taught herself to write with her left and, in 1992, she published Elegy for a Breast 哀悼乳房 (adapted for the screen as 2 Become 1). Later on, in an effort to regain movement in her affected hand, Xi Xi focussed on handicrafts. Over the years, she crafted dolls houses, puppets and stuffed animals, and eventually teddy bears. Her bears started out within the familiar tradition of the Western teddy — the toy bears inspired by Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt in the 1900s and Winnie-the-Pooh in the 1920s — but over time Xi Xi developed her own, uniquely Chinese breed.

Xi Xi’s The Teddy Bear Chronicles 縫熊志 appeared with Joint Publishing HK in 2009. It consists of short essays influenced by the biographical style, or 列傳, of Sima Qian (司馬遷, 206 BCE-220 CE), the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty. Xi Xi paired her biographical sketches with images from her ursine pantheon of handmade teddies.

The following excerpt appeared in China Heritage with the translator’s permission in 2017. The Teddy Bear Chronicles was published in English translation in Hong Kong and New York in 2021, shortly before Xi Xi’s death in 2022. The teddy bears had been donated to the library of Chinese University of Hong Kong in 2018.

— GRB

***

Zhuangzi

Zhuangzi was a fascinating individual with more stories up his sleeve than anybody else in the world. Some of his stories are long, others are short; but they’re all interesting and superbly imaginative. They’re also full of paradoxes — to use a favourite expression of his (even though it’s become a terrible cliché). In one instance, a gigantic bird capable of flying ninety thousand li in one flap of the wing turns out to be the transformation of a minuscule fish. In another, a massive gourd that was hopeless as a water jug could well serve as a sailing boat. Then there’s that huge, useless tree, which delights in being considered useless. Since nobody wants it for anything, it can come to no harm. Why wouldn’t it be happy about that?

莊子真是世界上最多故事的妙人。他的故事大大小小,有趣,充滿想像,充滿,用他的詞匯雖然這詞匯已濫得有點肉麻:弔詭。例如有時是很大很大的鳥,一飛九萬里,可這大鳥是從一尾很小很小的魚變成的。有時是很大很大的葫蘆,可不要用來盛水,而是最好當遊船﹔有時呢是一棵沒用的大樹,你說它沒用,它可高興了,你就不會打它的主意,損害它,它豈不悠哉游哉。

Zhu Guangqian, who founded the study of aesthetics in modern China, wrote an essay discussing three ways to look at ancient pine trees. It’s interesting enough. But aeons before this, Zhuangzi had already introduced another, completely different point of view: that of the tree itself. Once we can imagine a tree with its own point of view, then we won’t go around thinking ourselves better than trees, or imposing our will upon them. From then on, we will respect trees. Starting from a sense of respect for trees, we can go on to respect other things.

朱光潛以往寫過篇三種角度看一棵古松的文章,很有意思﹔不過三種角度都把樹木對象化,莊子老早告訴我們,其實還有另外一種角度﹕樹木自己的角度。如果想到還有這麼一個樹木本身的角度,你就不會看輕樹木,不會對樹木強加自己的主觀意志,從而尊重樹木。從尊重一棵樹木出發,你就會懂得尊重其他。

Zhuangzi is constantly teaching us how to see things differently: from the opposite angle; from the contrary point of view. The idea is to reveal how not to be stubborn, biased, or prejudiced. In one case, he asks: How can a summer-born bug whose life spans just a single season, ever hope to understand ice or snow? He goes on to explain why the summer bug has no way of understanding such things. It should be aware of its limitations, and accept the possibility of other points of view. It shouldn’t go around judging things related to other seasons from its own limited perspective, that of a summer bug. Humans perpetuate the error made by the summer-born bug, and have been doing so for more than two thousand years.

莊子總是教我們用不同的角度看物事,相反的角度,逆向的角度,不要偏執成見。試想想,生長一季的夏蟲,如何明白冰雪是什麼。這是夏蟲沒有辦法的事,但牠至少要知道自己的局限,其他角度的可能,不要死抱夏蟲之見去判斷另一個季節的物事。二千多年來,我們人類的社會,仍然犯著夏蟲的毛病。

They say that a certain monarch once offered Zhuangzi the post of Prime Minister. He refused. Now that is an earnest renouncement of fame and fortune. His stories were certainly not idle chit-chat. He practised what he preached.

據說某某國君想請他做宰相,他拒絕了,這是對名利真正的捨棄。他的故事,可不是說說就算。

***

***

Sometimes Zhuangzi himself becomes the protagonist of his stories. The most famous is about a dream he once dreamed. He dreams of a butterfly, then imagines himself as the butterfly; until he no longer knows whether he is Zhuangzi dreaming of a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming of a man called Zhuangzi. It has to be the best dream in history. Since when did we stop having wonderful dreams like that? Since when did our dreams become nothing more than objects for psychopathology?

有時,莊子連自己也成為故事的主人翁,最著名的是他一次做夢,夢見蝴蝶,於是從蝴蝶設想,到頭來不知是莊周夢見蝴蝶,抑或是蝴蝶夢見莊周。這夢,真是人類最甜美的夢。什麼時候,我們失去了這種美夢呢?什麼時候,我們的夢,成為病態心理學分析的對象?

The Zhuangzi bear I’ve made is most likely dreaming of butterflies in his sleep, too. You’ll see he has a wawa pillow, with a doll’s face at either end. Where is he sleeping? Under a big tree? On the grass? Just as a butterfly would, he has perched himself on top of a hedge for a nap.

我縫的莊子在睡覺時夢見蝴蝶了吧。他枕的是「娃娃枕」,兩頭各有一張娃娃臉。他睡在哪裡?大樹下,草地上?原來他一如蝴蝶,睡在一叢樹籬的頂端。

— translated by Christina Sanderson, revised by John Minford

***

Source:

- Rings, Tracks, Bears in A Wairarapa Miscellany (Rings, Tracks, Bears), China Heritage, 2017

***