‘Master Wei’ 韋公子 — ‘A Rake’s Progress’ — translated by John Minford from Pu Songling’s (蒲松齡, 1640-1715) Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異 is the latest addition to Nouvelle Chinoiserie 奇趣漢學 and Wairarapa Readings 白水札記 in China Heritage. These selections celebrate the variety and vibrancy of China’s literary heritage.

In Nouvelle Chinoiserie we introduce literary texts and translations aimed at students of traditional Chinese letters who are interested in the world that lies beyond the narrow confines and demands of contemporary institutional pedagogy. They also reflect the long-term interest of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology in ‘cultivation’ 修養. Henceforth, Wairarapa Readings will be included in ‘Nouvelle Chinoiserie’ under Projects on the China Heritage site.

The translation is followed by a parallel text.

— The Editor

China Heritage

18 June 2018

***

Reading Strange Tales:

- John Minford and Tong Man 唐文, ‘Whose Strange Tales?’, East Asian History, Nos.17/18 (June/December 1999): 1-48

- Pu Songling, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異, translated and edited by John Minford, Penguin Classics, 2006

- The Tiny Bird-Track, in The Year of the Rooster, On Reading, China Heritage, 15 January 2017

- John Minford, Herbert Giles (1845-1935) and Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, a lecture in the series ‘A Lineage of Light’, China Heritage, 25 May 2017

- Weird Accounts 志怪, in Spectres in the Seventh Month, China Heritage, 4 September 2017

- P.K.’s Strange Tales 也斯聊齋, China Heritage, 6 September 2017

- Pu Songling, The Dog Lover (Dog Days II), trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 24 February 2018

- Pu Songling, The Midget Hound 小獵犬 (Dog Days VI), trans. John Minford, China Heritage, 11 May 2018

- John Minford, Nouvelle Chinoiserie & the Obsessions of Master Pu, China Heritage, 1 June 2018

Introductory Note

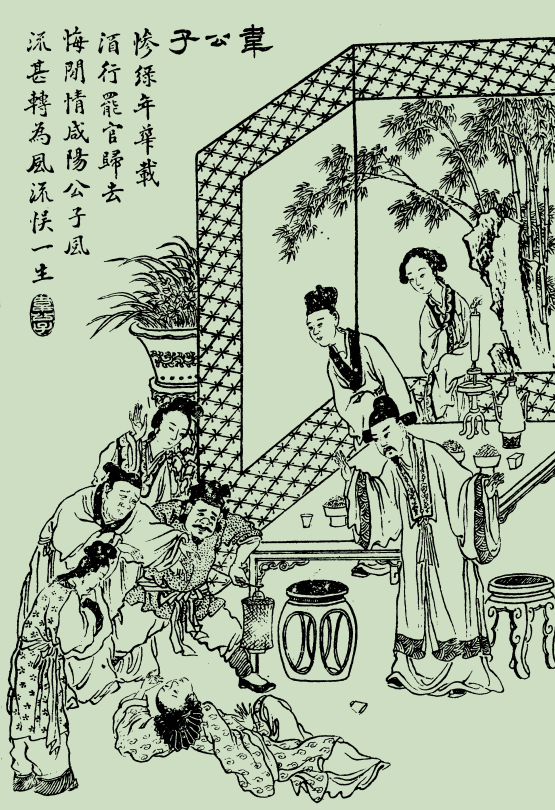

This is a characteristic medium-length Pu Songling tale, with a well-developed plot and carefully studied characterisation. One of the late-nineteenth-century commentators, (in the much reprinted Xiangzhu Liaozhaizhiyi tuyong 詳注聊齋誌異圖詠, popular mainly for its excellent illustrations) advises the reader, in a brief interlinear note, to compare this story with the longer and more famous ‘Lotus Fragrance’ 蓮香 (included in my 2006 selection, Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio, no. 54, pp.211-228).

‘Lotus Fragrance’ deals at greater length with a triangular relationship, though in that case it involves a man and two women, one of whom is a fox-spirit/singsong girl, the other a seductive ghost. The three of them are ultimately united in ‘a harmonious bigamous relationship’. The modern commentators tend to interpret ‘A Rake’s Progress’ 韋公子 as a simple moral tale, which surely does an injustice to Pu Songling.

He has given us a subtle study of a libertine from a wealthy family brought face to face with the tragic consequences of his insatiable philandering in the course of two incestuous encounters, one with a pretty young actor (and his equally pretty wife), one with a glamorous singsong girl. He pays the price of his pleasure and on his death-bed expresses remorse. It is in some ways reminiscent of the great late-Ming novel of sexual mores Golden Lotus 金瓶梅, but written in a more subtle and restrained manner (and of course in pithy Classical Chinese).

A delightfully humorous touch occurs towards the end of the story, when the puritanical uncle refuses his childless nephew permission to adopt one of his grandsons, for fear that the boy will be led astray. The ageing Rake’s immediate response to this (I suppose nowadays we would call it a relapse) is to think of inviting his former lover (and illegitimate son), the handsome female impersonator Luo Huiqing, to come and join his menage (by now he has five or six wives). His womenfolk understandably draw the line at this proposal. Pu Songling comments with his usual brevity: ‘So he dropped the idea.’

In his concluding comment as Chronicler of the Strange, after lamenting the young man’s vicious life (he is a beast with a human face 人頭而畜鳴者耶), Pu Songling remarks wrily that despite everything, at least his unfortunate children (the actor and the singsong girl) had become distinguished members of the demi-monde:

雖然風流公子所生子女,在風塵中亦皆擅場。

— John Minford

A Rake’s Progress 韋公子

Pu Songling 蒲松齡

Translated by John Minford

There was a young man named Wei, of a well-to-do family in the town of Xianyang, in the north-western province of Shaanxi.[1] He was a thoroughly dissolute fellow, a libertine who enjoyed sexual relations with every one of the attractive maidservants and serving-women employed in his family establishment. He set off one day with several thousand taels of silver on a personal Grand Tour, intending to visit every pleasure-quarter and sample all the famous singsong-girls of the land. If he came across a girl who was even moderately attractive, he spent a night or two with her; if a girl pleased him greatly, he stayed three months.

Meanwhile his uncle, a prominent official, had reached retirement and returned to live in the family home. He was extremely indignant at his nephew’s depraved way of life, and proceeded to hire a scholar of some repute to take him in hand, setting them up in a separate compound, where his nephew was closeted with various other cousins for the purposes of uninterrupted study. But Young Wei simply waited till nightfall, by which time his tutor was sound asleep, and then climbed out of the compound, not returning until dawn the following day. This continued for quite some time. One night, however, he slipped and broke his arm, and his escapade came to the tutor’s notice. His uncle, being informed, gave his nephew such a thrashing that he was quite unable to stand up and had to be confined to bed, where gradually his wounds healed. When he was recovered, the uncle entered into an agreement with him: if the young man was willing to work diligently, excel his cousins in their studies, and acquire a certain skill at prose composition, he would give him back his freedom; but if he ever tried to escape again, he would receive another thrashing.

Young Wei was an extremely intelligent lad, and so far as his studies went, he was easily able to surpass his uncle’s expectations. After a few years of this routine, he succeeded in passing out with honours in the Provincial Master’s Examination, the second of the steps on the ladder towards officialdom. He suggested that now might be the time to revoke the terms of their agreement, but his uncle was unrelenting. Later he went up to the Capital to prepare for the Metropolitan Examination, and his uncle sent an old family servant with him to act as chaperone, with instructions to keep a daily record of his activities. In this way several years went by without Wei being free to commit any of his former misdemeanours. Finally he passed the Doctorate, and the old uncle relented, whereupon the young man returned at once to his old ways. But this time, since he was still nervous of being discovered by his uncle, when frequenting the pleasure-houses he always assumed another name.

One day, he was passing through the provincial capital Xi’an, when he encountered a young actor, a female impersonator by the name of Luo Huiqing, a pretty lad of some sixteen or seventeen years, as beguiling as any girl. Wei took a great fancy to him. They spent the night together, and with time he grew greatly attached to Luo, and showered him with gifts. He heard tell that Luo had recently married a comely young wife, and intimated to him that he would like to meet her as well. Luo had no objections, and that night he brought along his wife, and they all shared the same bed. This menage continued for several days, and a deep bond of affection grew up between the three of them. Wei even suggested taking them both home with him to Xianyang, and enquired what other family they had.

‘My mother passed away years ago,’ replied Luo. ‘But my father is still alive. In fact, Luo is not my real name. My mother used to work for the Wei family of Xianyang, but was later sold to the Luo family. Four months later she gave birth to me. If I were to go to Xianyang with you, I could make some enquiries about my father.’

Wei asked in some consternation what his mother’s name had been. When the boy told him it was Lü, Wei was visibly shaken and broke out in a cold sweat. She had indeed been one of his family’s maidservants. He said nothing further, but at dawn he gave his young friend a generous present and urged him to seek a new profession. Then he invented a pretext and went on his way, promising to return and make contact with them again.

Subsequently Wei was made Prefect of the city of Soochow, and there he met a beautiful young singsong-girl by the name of Shen Weiniang. He was utterly captivated by her charms, and in the course of a night spent making love to her,[2] he asked her in a playful tone:

‘Does your name Weiniang come from that famous line by the poet: “Oh Du Weiniang! Song of a sweet spring breeze!”?’

‘No,’ she replied. ‘It has nothing to do with that. When my mother was seventeen years old, she herself was a famous singsong-girl, and a young gentleman from Xianyang with the same name as yourself, a Mr Wei, stayed with her for three months.[3] He even promised to marry her. Then he went away, and eight months later she gave birth to me. She called me Weiniang, Miss Wei, after my real father’s family name. When he left he gave her a mandarin duck made of solid gold, which I still have in my possession. Afterwards we heard nothing more of him. My poor mother was heart-broken and died of grief. When I was three years old, Madame Shen took me in and trained me up, so I took her family name instead.’

Hearing her story, Wei was overwhelmed with shame and remorse. He was silent for a while. Then he conceived of a desperate scheme. Rising from bed, he trimmed the lamp, and invited the girl to drink with him, secretly slipping a quantity of poison into her cup. She had no sooner swallowed the wine than she began screaming in agony. Members of the household came rushing in, but she was already dead.

Wei sent for the bawd and handed over the girl’s body, together with a substantial bribe. But Miss Wei’s regular clientele had included several local gentlemen of prominent families, and when they heard of her untimely death, they were not content to leave things as they were but themselves paid the bawd handsomely to take the matter to court. Wei panicked and spent all he had in an effort to save himself from a charge of murder. In the end he was dismissed from his post for nothing more serious than dissolute conduct, and returned home to Xianyang.

By this time, he was thirty-eight years old, and had come to feel a degree of remorse for his past misconduct. He had five or six wives and concubines, but none of them had borne him a child. He wished to adopt one of his uncle’s grandsons, but the uncle, fearing that the boy would be contaminated by his nephew’s debauched character, insisted on delaying the adoption until Wei had reached an advanced old age.

Wei was incensed at this, and proposed to send for Luo Huiqing, the actor, instead. But his womenfolk would not hear of this, and so he dropped the idea.

Several years later, he was afflicted with a sudden illness, during which he kept pounding his chest and crying out:

‘To ravish maid-servants and frequent singsong-houses — such behaviour is unfit for any human being!’

When his uncle heard tell of this he sighed:

‘He must surely be close to death now!’

He sent over one of his grandsons, the son of his second son, to tend to the dying man as if he were his own father. A month later Wei died.[4]

Notes

[1] The city of Xianyang, on the northern bank of the River Wei, some twelve miles from the provincial capital city of Xi’an was, from 250 BCE, the capital of the draconian north-western state of Qin, and it was from here that the infamous First Emperor of Qin directed his conquest of China. He later moved the capital across the river to Xi’an (or, as it was then known, Chang’an).

[2] Xia 狎 is the key-word so often used by Pu Songling for sexual intimacy, as Zhu Yixuan comments in his excellent Liaozhai Dictionary (Tianjin 1991), p.502.

[3] Presumably by this time, Wei, having become a high-ranking official, no longer felt the need to conceal his real name.

[4] In an interesting textual variant, the printed editions have Wei committing suicide, 尋卒, in place of 果死.

- The commentator He Shouqi says this story is a warning — 殷鑑 — against the evil consequences of carnal desire 漁色. — Trans.

Parallel Text

A Rake’s Progress 韋公子

Pu Songling 蒲松齡

Translated by John Minford

There was a young man named Wei, of a well-to-do family in the town of Xianyang, in the north-western province of Shaanxi. He was a thoroughly dissolute fellow, a libertine who enjoyed sexual relations with every one of the attractive maidservants and serving-women employed in his family establishment. He set off one day with several thousand taels of silver on a personal Grand Tour, intending to visit every pleasure-quarter and sample all the famous singsong-girls of the land. If he came across a girl who was even moderately attractive, he spent a night or two with her; if a girl pleased him greatly, he stayed three months. 韋公子,咸陽世家。放縱好淫,婢婦有色,無不私者。嘗載金數千,欲盡覓天下名妓,凡繁麗之區無不至。其不甚佳者信宿即去,當意則作百日留。

Meanwhile his uncle, a prominent official, had reached retirement and returned to live in the family home. He was extremely indignant at his nephew’s depraved way of life, and proceeded to hire a scholar of some repute to take him in hand, setting them up in a separate compound, where his nephew was closeted with various other cousins for the purposes of uninterrupted study. But Young Wei simply waited till nightfall, by which time his tutor was sound asleep, and then climbed out of the compound, not returning until dawn the following day. This continued for quite some time. One night, however, he slipped and broke his arm, and his escapade came to the tutor’s notice. His uncle, being informed, gave his nephew such a thrashing that he was quite unable to stand up and had to be confined to bed, where gradually his wounds healed. When he was recovered, the uncle entered into an agreement with him: if the young man was willing to work diligently, excel his cousins in their studies, and acquire a certain skill at prose composition, he would give him back his freedom; but if he ever tried to escape again, he would receive another thrashing. 叔亦名宦,休致歸,怒其行,延明師置別業,使與諸公子鍵戶讀。公子夜伺師寢,逾垣歸,遲明而返。一夜失足折肱,師始知之。告公,公益施夏楚,俾不能起而始藥之。及愈,公與之約:能讀倍諸弟,文字佳,出勿禁;若私逸,撻如前。

Young Wei was an extremely intelligent lad, and so far as his studies went, he was easily able to surpass his uncle’s expectations. After a few years of this routine, he succeeded in passing out with honours in the Provincial Master’s Examination, the second of the steps on the ladder towards officialdom. He suggested that now might be the time to revoke the terms of their agreement, but his uncle was unrelenting. Later he went up to the Capital to prepare for the Metropolitan Examination, and his uncle sent an old family servant with him to act as chaperone, with instructions to keep a daily record of his activities. In this way several years went by without Wei being free to commit any of his former misdemeanours. Finally he passed the Doctorate, and the old uncle relented, whereupon the young man returned at once to his old ways. But this time, since he was still nervous of being discovered by his uncle, when frequenting the pleasure-houses he always assumed another name. 然公子最慧,讀常過程。數年中鄉榜。欲自敗約,公鉗制之。赴都,以老僕從,授日記籍,使志其言動。故數年無過行。後成進士,公乃稍弛其禁。公子或將有作,惟恐公聞,入曲巷中輒托姓魏。

One day, he was passing through the provincial capital Xi’an, when he encountered a young actor, a female impersonator by the name of Luo Huiqing, a pretty lad of some sixteen or seventeen years, as beguiling as any girl. Wei took a great fancy to him. They spent the night together, and with time he grew greatly attached to Luo, and showered him with gifts. He heard tell that Luo had recently married a comely young wife, and intimated to him that he would like to meet her as well. Luo had no objections, and that night he brought along his wife, and they all shared the same bed. This menage continued for several days, and a deep bond of affection grew up between the three of them. Wei even suggested taking them both home with him to Xianyang, and enquired what other family they had. 一日過西安,見優僮羅惠卿,年十六七,秀麗如好女,悅之。夜留繾綣,贈貽豐隆。聞其新娶婦尤韻妙,私示意惠卿。惠卿無難色,夜果攜婦至,三人共一榻。留數日眷愛臻至。謀與俱歸。問其家口。

‘My mother passed away years ago,’ replied Luo. ‘But my father is still alive. In fact, Luo is not my real name. My mother used to work for the Wei family of Xianyang, but was later sold to the Luo family. Four months later she gave birth to me. If I were to go to Xianyang with you, I could make some enquiries about my father.’ 答雲:母早喪,父存。某原非羅姓。母少服役於咸陽韋氏,賣至羅家,四月即生余。倘得從公子去,亦可察其音耗。

Wei asked in some consternation what his mother’s name had been. When the boy told him it was Lü, Wei was visibly shaken and broke out in a cold sweat. She had indeed been one of his family’s maidservants. He said nothing further, but at dawn he gave his young friend a generous present and urged him to seek a new profession. Then he invented a pretext and went on his way, promising to return and make contact with them again. 公子驚問母姓,曰:姓呂。生駭極,汗下浹體,蓋其母即生家婢也。生無言。時天已明,厚贈之,勸令改業。偽托他適,約歸時召致之,遂別去。

Subsequently Wei was made Prefect of the city of Soochow, and there he met a beautiful young singsong-girl by the name of Shen Weiniang. He was utterly captivated by her charms, and in the course of a night spent making love to her, he asked her in a playful tone: 後令蘇州,有樂伎沈韋娘,雅麗絕倫,愛留與狎。戲曰:

‘Does your name Weiniang come from that famous line by the poet: “Oh Du Weiniang! Song of a sweet spring breeze!”?’ 卿小字取春風一曲杜韋娘耶。

‘No,’ she replied. ‘It has nothing to do with that. When my mother was seventeen years old, she herself was a famous singsong-girl, and a young gentleman from Xianyang with the same name as yourself, a Mr Wei, stayed with her for three months. He even promised to marry her. Then he went away, and eight months later she gave birth to me. She called me Weiniang, Miss Wei, after my real father’s family name. When he left he gave her a mandarin duck made of solid gold, which I still have in my possession. Afterwards we heard nothing more of him. My poor mother was heart-broken and died of grief. When I was three years old, Madame Shen took me in and trained me up, so I took her family name instead.’ 答曰:非也。妾母十七為名妓,有咸陽公子與公同姓,留三月,訂盟婚娶。公子去,八月生妾,因名韋,實妾姓也。公子臨別時,贈黃金鴛鴦今尚在。一去竟無音耗,妾母以是憤悒死。妾三歲,受撫於沈媼,故從其姓。

Hearing her story, Wei was overwhelmed with shame and remorse. He was silent for a while. Then he conceived of a desperate scheme. Rising from bed, he trimmed the lamp, and invited the girl to drink with him, secretly slipping a quantity of poison into her cup. She had no sooner swallowed the wine than she began screaming in agony. Members of the household came rushing in, but she was already dead. 公子聞言,愧恨無以自容。默移時,頓生一策。忽起挑燈,喚韋娘飲,暗置鴆毒杯中。韋娘才下嚥,潰亂呻嘶。眾集視則已斃矣。

Wei sent for the bawd and handed over the girl’s body, together with a substantial bribe. But Miss Wei’s regular clientele had included several local gentlemen of prominent families, and when they heard of her untimely death, they were not content to leave things as they were but themselves paid the bawd handsomely to take the matter to court. Wei panicked and spent all he had in an effort to save himself from a charge of murder. In the end he was dismissed from his post for nothing more serious than dissolute conduct, and returned home to Xianyang. 呼优人至,付以尸,重賂之。而韋娘所與交好者盡勢家,聞之皆不平,賄激优人訟于上官。生懼,瀉橐彌縫,卒以浮躁免官。

By this time, he was thirty-eight years old, and had come to feel a degree of remorse for his past misconduct. He had five or six wives and concubines, but none of them had borne him a child. He wished to adopt one of his uncle’s grandsons, but the uncle, fearing that the boy would be contaminated by his nephew’s debauched character, insisted on delaying the adoption until Wei had reached an advanced old age. 歸家年才三十八,頗悔前行。而妻妾五六人,皆無子。欲繼公孫;公以門無內行,恐兒染習氣,雖許過嗣,必待其老而後歸之。

Wei was incensed this, and proposed to send for Luo Huiqing, the actor, instead. But his womenfolk would not hear of this, and so he dropped the idea. 公子憤欲招惠卿,家人皆以為不可,乃止。

Several years later, he was afflicted with a sudden illness, during which he kept pounding his chest and crying out: 又數年忽病,輒撾心曰:

‘To ravish maid-servants and frequent singsong-houses — such behaviour is unfit for any human being!’ 淫婢宿妓者非人也。

When his uncle heard tell of this he sighed: 公聞而歎曰:

‘He must surely be close to death now!’ 是殆將死矣。

He sent over one of his grandsons, the son of his second son, to tend to the dying man as if he were his own father. A month later Wei died. 乃以次子之子,送詣其家,使定省之。月余果死。