Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXXIV, Part V

池魚堂燕

Chapter Thirty-four of Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, the penultimate chapter in the collection, consists of a series of essays related to China’s intellectual life and its stillborn public sphere. Four of the five sections in this chapter were published over the years leading up to the Xi Jinping era. Given that most of this material was not previously available in digital form, I decided to digitise and publish them as background to the final chapter in Tedium, the title of which is ‘An Irrealis Mood’. A version of that concluding chapter was drafted for ‘Knowledge, Ideology and Public Discourse in Contemporary China’, a conference organised by Sebastian Veg and held at L’École des hautes études en sciences sociales (EHEES) in Paris on 13-14 June 2024.

This chapter consists of the following sections:

- Time’s Arrows

- The Revolution of Resistance

- Have We Been Noticed Yet?

- Chinese Visions: A Provocation

- On China’s Editor-Censors

- Ethical Dilemmas — notes for academics who deal with Xi Jinping’s China

The first three of these works, written between 1998 and 2001, were a continuation of a series of commentaries, academic analyses, translations and books that I published from 1978 that include: records of my encounters with Ai Qing and Ding Ling in 1978 and 1979 respectively, The Wounded (1979), my contributions to Trees on the Mountain (1983), an overview of the 1983 Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign (1984), Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience (1986, rev. ed. 1988), the Chinese-language essays on culture and politics published in The Nineties Monthly (1986-1991), extended studies of Liu Xiaobo (1990) and Dai Qing (1991), New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices (1992), my contribution as lead academic adviser and writer to the documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace (1995), as well as the books Shades of Mao: the Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (1996) and In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture (1999). Two other works in this series — A Provocation and Ethical Dilemmas — relate to China’s relative openness at the time of the 2008 Beijing Olympics and the lengthening shadow of the Gate of Darkness 黑暗的閘門, yet again, from 2012. ‘On China’s Editor-Censors’ is one of Xu Zhangrun’s Ten Letters from a Year of Plague. Today, its message is more resonant than ever.

***

Xu Zhangrun’s A Letter to My Editors and to China’s Censors — 許章潤《致知編輯同人》— was published by ChinaFile on 18 May 2021. As I noted in the translator’s introduction:

Over the years, a number of writers have directly addressed China’s censors, a vast and lavishly funded system of disparate individuals and groups that ranges from high-level ideologues in Beijing like Politburo Standing Committee Member Wang Huning to lowly Internet invigilators in the provinces.

In January 2021, Xu Zhangrun, perhaps China’s most famous dissident legal scholar, released a letter addressed not only to China’s censors but also to the editors and publishers with whom he had worked for decades. That essay, translated below, is Letter Eight in his Ten Letters from a Year of Plague (庚子十劄), a collection that, read as a whole, is an account of the persecution he has suffered since he published a fierce point-by-point appraisal of the Xi Jinping era and warned of the calamities that lay ahead. The letters also comprise an agonized farewell both to his former life and to China’s short-lived era of progressive reform.

In the weeks following the appearance of Xu’s jeremiad in late July 2018, all evidence of his existence was gradually and meticulously scrubbed from the Chinese Internet. In response to what amounted to an official act of damnatio memoriae, Xu issued another critique in which he asked, “do you honestly believe you can simply make me evaporate and disappear entirely from the ranks of humanity?” Despite being reduced to the status of what in the Soviet Union was known as a “former person,” Xu has continued to circulate his writings as best he can in China as well as in the international Chinese media. A bilingual archive of his “rebellion in writing” is also available.

As a result of his ongoing defiance, Xu Zhangrun was stripped of all of his professional duties and rights as well as repeatedly harassed by both the police and other state security organs. While detained by police for a week in July 2020, Tsinghua University, one of China’s most prestigious institutions where Xu had worked for nearly two decades, sacked him and confiscated his pension fund. Ever since, he has survived on his savings and a meagre unemployment benefit. Living in relative isolation and under constant surveillance, he is forbidden from receiving any support from friends or admirers.

The following letter was written after an encounter that Xu Zhangrun had with a number of his former editors in late December 2020. In a record of that occasion, he noted that “my remaining friends are as few as the scattered stars at dusk” and that “here I was, an unemployed nobody who, having come into town to buy groceries, had happened to encounter a gathering of ‘somebodies’ celebrating their latest academic achievements.” It was a painful affair for all involved. At the end of the reverie that he composed that night, Xu mused: “In Heaven’s Will there is perhaps a sense of decency. Humankind, too, may boast some saving grace. Regardless, the tortuous beauty of this moonlit night leaves me feeling as though my soul has been rent asunder.”

Below, Xu invokes the philosopher Hannah Arendt, who wrote: “Truth, though powerless and always defeated in a head-on clash with the powers that be, possesses a strength of its own: whatever those in power may contrive, they are unable to discover or invent a viable substitute for it. Persuasion and violence can destroy truth, but they cannot replace it.”

Arendt also observed that: “Where everybody lies about everything of importance, the truth-teller, whether he knows it or not, has begun to act; he, too, has engaged himself in political business, for, in the unlikely event that he survives, he has made a start toward changing the world.”

Xu Zhangrun is just such a truth-teller.

***

A Note on the Translation

This is an edited translation of “Letter Eight” 致知編輯同人 in Xu Zhangrun’s Ten Letters from a Year of Plague 庚子十劄, the Chinese original of which was published in New York in July 2021. Deletions and annotations have been made with the author’s permission. The editorial style of the original publication in ChinaFile has been retained and I am grateful to Susan Jakes and Sara Segal-Williams for their meticulous care.

My translation is followed by the edited text of the original.

—Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

12 June 2024

***

Related Material

- The Editor & Xu Zhangrun, Introducing Xu Zhangrun’s Ten Letters from a Year of Plague, 11 February 2021

- Xu Zhangrun, A Farewell Letter to My Students, ChinaFile, 9 September 2021

- Xu Zhangrun, Xi’s China, the Handiwork of an Autocratic Roué, The New York Review of Books, 9 August 2021

- Xu Zhangrun, Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear, 24 February 2020

- Xu Zhangrun, Cyclopes on My Doorstep, 22 December 2020

- Composed of Eros & of Dust — Xu Zhangrun Goes Shopping, 31 December 2020

- Murong Xuecun, An Open Letter to the Nameless Censor, China Story Yearbook 2013: Civilising China

- Xu Zhiyuan, Elephants & Anacondas, 28 June 2017

- A View on Ai Weiwei’s Exit, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 26 (June 2011)

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage

- Great Fire (English); Great Fire (簡中), anonymous activist anti-censorship website

- Censorship in China, Reading the China Dream, 3 June 2024; also Reading and Writing under Censorship in China

***

Even though everyone in the publishing industry is a victim of the system as a whole, most of them also collaborate with and profit from censorship itself. Ultimately, no one is an innocent bystander. …

The system doesn’t stop with imposing its will from the outside, for it has long since inveigled its way into every heart, mind, and relationship. It penetrates your being in such a fashion that you are no longer aware of its discreet operations. It generates anxiety and excites terror in such subtle ways that you can never feel truly alone or be entirely at peace. It can do so because it inculcates an awareness of the danger of transgressing its “red lines.” Even when you just want to get on with life, it makes you hesitate before you dare take a step.

— Xu Zhangrun

***

A Letter to My Editors and to China’s Censors

Xu Zhangrun

Translation and annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

‘The Lost Poetry of Our Talk’

My Dear Former Editors,

I hope you’ll indulge me by finding time to read this letter. Apart from my fellow educators and students, those I had the most to do with over the years were you, my editors.

[Note: See A Farewell Letter to My Students, ChinaFile, 9 September 2021.]

While for me the bond between teacher and student fostered a sense of “being at home,” publishing houses and editors were akin to a courtyard that was attached to the spacious main building of my true vocation. You have all been part of the intimate world of loved ones and friends that provided a haven from the outside world, although you also determined the outer limits of our self-imposed confinement.

My academic home offered me a contemplative environment in which to work, and the courtyard you provided was like an open space in which I could perambulate. The inner dwelling and your inviting courtyard were connected and air circulated freely between the two. When the skies were clear I could see the distant mountains or, when necessary, I might limit my gaze to the courtyard, occupying myself by following the twists and turns of its paths. At times, I might linger for a moment and contemplate the wisteria trailing along the walls as it was buffeted by a soft breeze or that glistened with drops of water from a recent shower. It’s hard to express the myriad of pleasures that I experienced there.

Within the confines of that courtyard, I would also encounter beguiling individuals who found pleasure in the blossoms that they cultivated. Although they readily took fright when some petals fell without warning, they would soon adjust to the changed climate; henceforth, they would speak in a whisper and tread more carefully.

Educators like me devoted themselves to teaching as well as to writing—the latter is both a personal pleasure and a professional requirement. It was essential that we were published, and that our work appeared frequently. So it was inevitable that people like me had a lot to do with people like you; we needed you and so we were in constant contact. However, as you well know, due to the dramatic change in my circumstances we have recently drawn apart. In fact, I’ve lost contact with all of you, and the people with whom I had been in constant communication have long since fallen completely silent. Given that I was all but drummed out of academia, it is hardly surprising that my former colleagues haven’t been in touch. Although, now that all of the editors with whom I’d previously worked so closely have also gone quiet, it really does feel as though the walls are closing in on me. To put it another way, it feels like dusk on a gloomy winter’s day. Now I wander aimlessly up and down the noisy streets of a northland that is cloaked in a suffocating smog-haze. I’m surrounded by flitting shadows and robbed of all human warmth.

Over the years, you inundated me with the academic books and journals you published, even if I hadn’t ordered or subscribed to them. Since 2018, that reliable tide gradually receded until it has now disappeared entirely. Of course, in the grander scheme of things it’s hardly worth mentioning even if, quite frankly, I’m left feeling abandoned and with a bitter taste in my mouth. It’s funny now to remember that I used to think those waves of books and journals were an annoyance; now I realize that they were as much a part of my life as the main sites of my work: my study at home, the library, and the lecture halls of Tsinghua University. Moving between those three places was the all-engrossing itinerary as well as being the rhythm of my daily round. Now I’m barred from the libraries and I’m even forbidden from entering a lecture hall; express deliveries of the latest publications no longer appear on my doorstep, and I’ve been reduced to relying entirely on my personal library. It’s stultifying.

When, upon occasion, I do venture into the city to browse the bookstores, although I’m relieved to see that both old friends and relatively recent acquaintances are still publishing lavishly produced tomes, I can’t help feeling resentful that my name is banned from appearing in print. It brings to mind that famous line by the great historian Chen Yinque, who said: “Though I’ll be dead soon enough, who knows when my work will ever appear?”

[Note: An internationally renowned scholar, Chen had chosen to stay in China after 1949 and was courted by Mao, who offered him a leading role in the reconstituted Academia Sinica. Chen said he would only take the position if Mao promised that neither he nor his colleagues would be required to study Marxist-Leninist dogma. In 1962, Mao’s powerful secretary, Hu Qiaomu, visited Chen at his university in Guangzhou. During their conversation, Chen made the remark quoted here by Xu Zhangrun. In reply, Hu declared:“Your work will be published soon and you’ll be with us for years to come.” In reality, Chen remained an isolated independent academic and died a broken man at the height of the Cultural Revolution. His unpublished works only appeared well after Mao’s demise. By comparing himself to Chen Yinque, Xu Zhangrun is saying in effect that he will not be published again until Xi Jinping is dead and buried.]

What’s to be done? At least I’ve finally been able to get another WeChat account, so I have access to a relatively wide range of material. I can even follow the goings on in academia; I suppose that’s something. Still, it’s somewhat like a window into a foreign land: there they all are, my former academic friends as well as the present intellectual stars, the businesspeople, and the retired bureaucrats. I follow their discussions and debates, as well as all the intellectual grandstanding; why, I can even learn all about their lavish recent trips around the country and their new ventures. Then there’s all the photos and the video clips that they post of themselves. All of it affords me a momentary escape from my sequestered courtyard; it’s as though I can take a stroll in the raucous streets outside. Thankfully, there are some decent types among them and, no matter how constrained the overall atmosphere is right now, I think to myself: surely some worthwhile things will still be produced that will leave a meaningful legacy for the future. After all, not everyone will be sentenced to social death like me! Frankly, the only things flourishing in my ongoing intellectual isolation are at best banal and mediocre. Or, to put it more plainly, once your academic life has been assassinated, as your mind atrophies, it is inevitable that your spirit will also wither. Those lines from “Temptation of the Poet” by the Welsh writer R.S. Thomas hold true:

“The temptation is to go back,

To make tryst with the pale ghost

. . . there to renew

The lost poetry of our talk

Over the embers of that world

We built together. . .”

They reflect both my present situation and my mental state.

To return, however, to the topic at hand, as editors and publishers I imagine that you now find yourselves in a harsh new era of “Qin Rule” [of the kind praised by Mao Zedong, who said of himself that he was Marx plus a modern-day version of the first emperor of the Qin dynasty]. You are in the sights of an odious regime that shores itself up by silencing dissenting voices. Although each publishing house is dealing with the situation in its own way, I know that you are all faced with an impossible dilemma and subject to all kinds of overt control as well as covert pressure.

China’s present totalitarian order has imposed a regime of censorship the likes of which has never been seen before. Under it, editing has become a particularly fraught occupation and shepherding anything through to publication a hazardous process. Everyone involved in the industry is hesitant. Authors feel that they are treading on thin ice. They still have to appeal to the good offices of publishers who may now respond in any number of ways. Those who contribute to what are presently deemed to be “core ideological publications” enjoy considerable state largesse, even if it means dealing with editors whose professionalism is at best a joke. The worst of them squeeze everything out of the system that they can while barring access to others. Such editors can constantly indulge themselves with well-lubricated banquets and frequent official trips to scenic spots. They cream money off the funds allocated for the various symposiums that they organize and rationalize it all by thinking they simply have to rip off the system to get by. Even though I’m no longer involved in the scene, I know that every law journal produced in China has such scumbags working for it. But those “core publications” are the worst.

Forgive my ranting: It’s been so long since I’ve seen any of you, and I have no one with whom to share my outrage, so I get quite emotional whenever I think about what’s going on. So, here I am, blurting out far more than I should.

I would hasten to add, however, that I remain extremely grateful that, throughout my own publishing career, I rarely encountered any editors who were motivated by such personal avarice. For the most part, they were all pretty much down to earth and quite a few of them were themselves really decent bookish types. Only now can I truly appreciate how lucky I was to have enjoyed such amicable working relationships. Then again, publishing tends for the most part to attract good people even though, like teaching, it isn’t a particularly popular career path.

As I’m writing this late at night, the faces of all of you—the editors I’ve worked with over the years—appear in my mind’s eye. I think back to all the times we agonized over a particular word or expression and how, sometimes, we ended up in heated arguments. Since it’s not possible to share my reminiscences with you over a drink, I am forced to savor these agreeable memories alone; never again will we wrangle over the minutiae of producing and printing my work, though I do remember an observation made by one particular editor-in-chief:

“Oh, that Xu Zhangrun, he’s just a drain on our resources. Do your best to avoid getting mixed up with his projects.”

Since all that’s left to me is the freedom to commit my thoughts to paper, my mind roams like an untethered horse and I’m writing down as many details here for you as I can so I don’t forget. . . As I embark upon my autumn years, my mind is often crowded with past memories, my heart sunk in the lost courtyard that I once shared with you all. I also increasingly recall details from my youth and, as my memory speaks, I’m doing my best to make sense of things and find thereby some meaning and solace. It’s a welcome respite from my present predicament; for a moment, the warm glow of the past dispels the encroaching chill of winter. I may well be alone, but I refuse to be lonely.

So, this is how you find me today, wandering around my virtual courtyard, chanting poems to myself and engaging with you in what Parisian leftists [like Gilles Deleuze and Claire Parnet in Dialogues] called a “conversation that is a double capture” [that is, an “a-parallel evolution of two beings who have nothing whatsoever to do with one another”]. It’s a form of mental exercise that keeps me from going completely stir-crazy. After all, a series of precipitous events suddenly thrust me into old age, the presumed summit of a person’s life and it’s rather knocked the wind out of me.

In a collection of enigmatic aphorisms titled All Things Are Possible, the Russian philosopher Lev Shestov wrote:

“To be irremediably unhappy—this is shameful. An irremediably unhappy person is outside the laws of the earth. Any connection between him and society is severed finally. And since, sooner or later, every individual is doomed to irremediable unhappiness, the last word of philosophy is loneliness.”

Aristotle spoke of the world “beyond the polis,” one in which only beasts and god could exist. As I have been exiled from the “polis,” I have therefore become, to all intents and purposes, beast-like and a “former person.”

Actually, this letter will be included in a book that I’ve been writing. It will be in a collection that is something of a psychological account of my recent travails. This effort, too, is part of my ongoing struggle to fend off loneliness. I fear, however, that even before my words have run their course, the well of my inspiration will run dry, my soul will freeze and my solitude increase as I’m reduced to abject solitude.

Perhaps countless others who have been “irredeemably unhappy” at other times and in other climes will one day open my account of solitude while reading by a window and join me in a spirit of understanding. Perhaps they will smile knowingly, lost in some inebriated state and, in that instant, they might be able to dispel for a moment the profound sense of isolation that all of us confront. Together, we can be like Shestov’s “unhappy ones.”

Now, as the gengzi lunar year [of February 2020-February 2021] draws to a close, I’m revealing myself to you here in an effort to express what I can only presume is a shared sense of misery and, by communicating with you in this way, also to seek some consolation in fellowship. . . These are, at best, self-absorbed musings, recorded as I contemplate the emptiness that has enveloped me. Even though I seek hereby your companionship, I can hardly expect you to embrace me with bear hugs.

An Editorial Education

My Dear Readers,

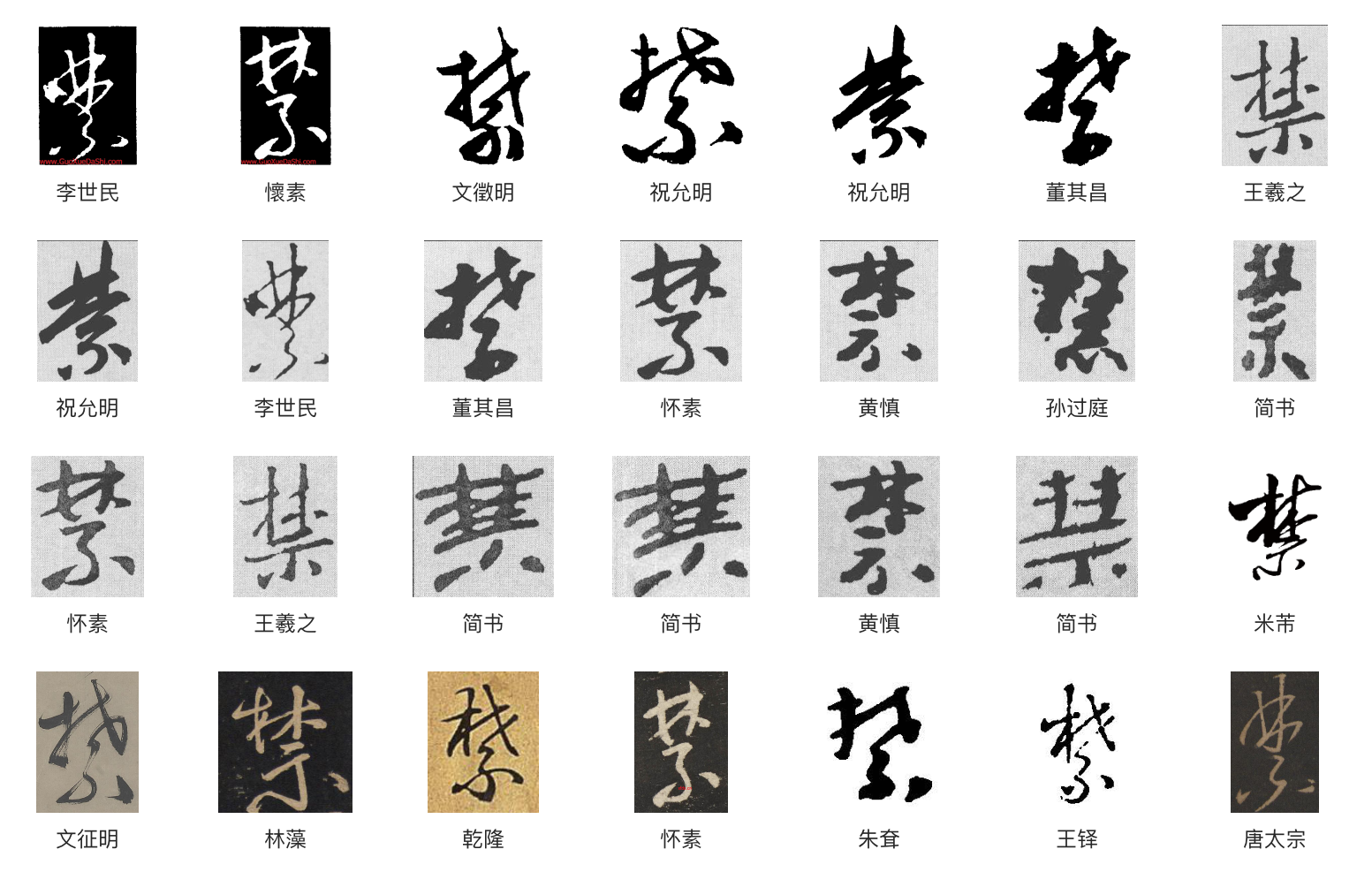

Over the years, I’ve been something of a part-time editor myself. You probably don’t know that in my callow youth I was very much taken with editing. [In the mid-1970s,] I compiled and wrote out the school paper that we regularly posted [written out in calligraphy on large sheets of paper and glued up on a dedicated wall]. In the process of editing, I’d add my own crude illustrations, do curlicues around the titles of articles, and play around with formatting. I even became fairly adept at selecting different character fonts and colors. I didn’t have much of a clue and pretty much did whatever I pleased; my aspirations were only limited by the fact that paper itself was in short supply.

Working on the school paper was one of the ways that helped me get through the harsh years of my youth [during the Cultural Revolution; the author was born in 1962]: all that dedicated concentration and the long hours of selfless industry helped dispel the feeling of desolation outside; added to that was my determination to overcome the limits of my frail and easily exhausted body. . . Hah, you’ll laugh if I dare suggest that those activities fired a maturity beyond my years.

After a night of toil, I’d set off in the faint light of dawn only to be subjected to the daily round of derision, contempt, and isolation at school. In class, I’d be called out and shamed in front of everyone, my work held up as a “negative teaching example”. . . During those years, school was a daily stint in purgatory. It’s ironic, but that’s how my lifelong dedication to teaching really began—and also how it has ended, with me now having been stripped of the right to teach at all. Fate can play such cruel jokes.

I often wondered what my teachers were really trying to teach. As intellectuals, they had been classified as the lowest of the low and had been subjected to the thought reform campaigns of the Communists and forced to endure frequent humiliation. Yet, here they were, imposing the [Mao-era politicized] education system on us. To a greater or lesser extent, they were the willing accomplices of the power holders. That the oppressors were also oppressed, or that those who had been wronged did wrong in turn, was, of course, hardly unique to that time. It was a reflection of the human condition itself; yet another example of the tragic nature of our existence and further evidence of the slavish underbelly of so many human relationships.

So-called social and political progress—if, indeed, “progress” as a substantive and meaningful concept is still desirable—should surely be about reducing and eliminating all kinds of enslavement while in the pursuit of greater, albeit invariably unattainable, freedom. Human beings are inherently free, just as they are also born enslaved and bound in the shackles of master-slave relationships. Freedom demands the breaking of those bonds so that the individual can enjoy autonomy and seek self-realization. It allows for the fullest expression of the self: our lusts, our enthusiasms and dynamism. Our innate sense of freedom is the closest thing we have to divinity. Our sense of transcendence is the means by which the world can truly be a place where human potential can be realized.

In the time of Jesus, this was the kind of salvation offered to people who were living in an irredeemable age; it is the same spirit that motivated the classical Confucians to pursue a positive role in the world. Without such possibilities, all of us are but adrift in an unprincipled realm of opportunism. If that is all there is, then people may just as well indulge in boundless hedonism and all kinds of craven behavior. Such individuals may like to think that they have broken free of convention and from their subjugation to others. In reality, however, they have only managed to enslave themselves in another way: they have sacrificed meaningful free will on the altar of mindlessness.

Maybe that’s why, as a university lecturer, I was always more interested in teaching my students how to think than in just expecting them to regurgitate the cut-and-dry formulas in the textbooks. I wanted to introduce them to the whole gamut of ideas and opinions regarding whatever the topic was under discussion. I was confident that was the best way for them to pursue the ideas in their own way and reach their own conclusions. Naturally, in the process, I’d share my views and idées fixes with them, but I was always keenly aware of the need not to hinder their intellectual curiosity. That’s why I never presented my take on things as being some kind of ex cathedra truth.

I suppose you could say that my pedagogical philosophy was typical of someone with a liberal mindset. After all, pronouncements like “the only possible conclusion is that. . .” are suited to law courts; monolithic approaches have no place in a university environment. Perhaps this is the basic difference between the kingdom of free thought and the mindset of the engineers, and from them come two completely different approaches, both in regard to social and political issues. You may well respond by claiming that society itself is a university and, in the “real world,” you’ll find yourself so embroiled in practicalities that you’ll soon forget most of what you’ve previously learned.

Of course, I acknowledge that school doesn’t result in a “finished product” as such, and that it is the life you have after your school years that really teaches you about how the world works. But a person’s school years have a crucial impact on their world view and their understanding of the meaning of life. In particular, as it was in my case, you learn a great deal about good and evil. You learn how to respond to failure. Most of all, you realize how you will react to inequality and injustice. You also learn how to deal with the peers who betray you and how people in positions of power can make life hard for you. School tempers you in ways that help you better cope with the abuses that you might suffer, say, at the hands of a malicious police force, or the insults hurled at you by strangers. Among other things, it taught me how to deal with the fact that, in a society like ours, you’re completely powerless. Of course, on top of all of that is the inescapable reality that our political system denigrates you and discriminates against you at every turn.

It’s during your school years that you learn a whole set of social and political responses so that you can deal with all of these things, although it also encourages you to blame everything on an unjust fate or your lack of awareness. But, then again, learning how to make excuses for yourself is also part of your education. Once you’re out of school, regardless of whether things go your way, or even when you end up suffering one disaster after another, the manner in which you respond to whatever hand you’re dealt is very much determined by the things you have learned actively or passively during your early years.

Forgive me: I’ve let myself get carried away again. Maybe I should illustrate my point by saying a little more about my own experience. You see, I was tainted from birth because I grew up in a reactionary family [according to the strict Maoist era class system. Xu’s father was classified as unredeemable because he had been a member of the Nationalist Party’s Youth Corps before the Communist conquest of 1949]. Being congenitally politically suspect, I was shunned by society and so I sought a refuge in art and drawing. That’s how I ended up editing the paper at school. Although I was regarded officially as being little better than social detritus, my school was quite happy to exploit my talents—I proved to be useful, like recycled trash. Even though they pretty much left me alone and despite my ongoing sense of displacement, despite a sense of hopelessness, I somehow harbored a vague hope for the future. I was determined at the same time as being all but paralyzed by indecision. I dreamed of getting into art school, but after having repeatedly flunked the entrance exams, I realized that my future lay elsewhere. Eventually, I got into university [where I studied law] and, despite my continued impoverished circumstances, I also did my best to keep up my interest in art. Gradually, time whittled away my old motivation and I gave up on it entirely.

It was only when I became a university lecturer that I realized that some of my old interests were also relevant to my new. That’s how I got back into editing. I initiated a series of books and became involved in setting up new academic journals. I particularly enjoyed commissioning articles and putting together thematic issues of my journals. For six years, I edited Tsinghua Legal Studies, confident that I could use it to elucidate some key legal principles [that were a feature of contemporary debates]. I also established Historical Jurisprudence, a book series that ran for over 10 years [and which is described in Letter Seven, addressed to my former students], in the hope that it would make a contribution to legal reform in China. As both an author and an editor, I came to appreciate the laborious yet exciting processes involved in editing and publishing. That’s why I can well understand the situation that now confronts you. I long ago learned that it doesn’t matter how enthusiastic you might be about something; I also learned that frustration and outrage are useless. Initially, you might feel generally hopeful about things but, over time, you come to realize that it’s best to be cautious even as you do your best to nurture a fragile sense of possibility and even as you strain to keep that deep-seated sense of despair at bay.

A Censoring Regime

All that means that I’ve had a lifelong involvement in editing and publishing; it also means that I’ve also been subject to constant censorship. Ah, the censoring eye: it’s a painstakingly cultivated form of vision, a kind of tireless invigilation trained to penetrate obfuscating skeins of words and divine dangerous intent lurking in the minutiae of ideas. As it sifts through mountainous haystacks in search of tell-tale needles, the censoring eye is always in a state of alert trepidation. Nothing escapes its scrutiny.

The fact of the matter is that, in China, one way or the other just about everyone works for the censorate—there’s the Party leaders, of course, but the regime also enlists the services of the broad masses and readers themselves. As you know all too well in your professional activities, there’s the kind of censorship that kicks in before something even gets published as well as post-production censorship. These are two aspects of a highly developed system that features such things as special-purpose censorship, routine censorship, emergency censorship, run-of-the-mill censorship, and task-focused censorship. Before any of that even comes into play, however, there’s a crucial internal, individual mechanism of self-censorship. [As the classic Tao Te Ching puts it:] “The myriad things are born from being and being is born from non-being.” Authors are so afraid of being “off message” from the get-go that, by and large, they are generally quite neurotic.

That’s why, if you want to identify the defining feature of the regime that has held sway in China for over 70 years, without a doubt it would be censorship, the tireless and boundless desire to shut people up and cripple their minds.

Why? Ours is a political system that was founded on lies and violence, and it can only maintain itself by telling more lies and pursuing ever greater violence. It is so afraid of the truth that it suppresses information, perverts people’s souls, and does everything it can to eliminate independent and free thought. To keep people safely cordoned off from the truth, it must plaster over every single crack in its edifice of falsehood. This is the modus operandi of all totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, be they in the East or in the West.

Being from a “reactionary family” I was, of course, congenitally tainted. That meant that, when I did something that didn’t measure up, it was never regarded as being due to a lack of ability, rather it was because my “bad attitude” had been bred in the bone. A “bad attitude” reflected a flawed “ideological orientation” that, it only stood to reason, meant that I had, and was, a “political problem.”

You didn’t need very much talent or skill to put together a high-school paper. My job was pretty formulaic. The devil was quite literally in the detail. Policing the contents of each issue of the newspaper demanded a very particular skill set. In the first instance, your class monitor and the head of your year’s study committee had to approve every item that might appear in the paper even before it was formally screened by the year’s student propaganda cadre and your own teacher. After they had all had a say, the head class monitor would have to make doubly sure that not even the slightest “potential problem” had eluded the various layers of vigilance. Sometimes, they’d call on the class committee to participate in the discussion and maybe even invite some relevant classmates, in particular the hyper-active Party types, so that they too could cast an eye over things. What kind of “potential problems” were they looking for? Something, anything, that might be construed as being sensitive or politically questionable, of course.

China’s “Red Dynasty” is a brilliant self-promoter, and over the years it has evolved numerous ways to celebrate itself. When you boil it all down, however, ultimately all the overblown rhetoric is really just about the “great, glorious, and infallible” leader [now shortened in Chinese to 偉光正]. So, the real art of avoiding political problems was about, first and foremost, making sure that you had the correct political perspective on things and, secondly, honing your abilities so you could identify and uncover enemies of the revolution. You had to do so with unwavering conviction and resolute application; there was no room for prevarication or fuzzy thinking. The Party-state was by nature flawless and must not be undermined in any way. That’s why the censors at my school were on the lookout for sly insinuations and underhanded remarks, while scanning everything in search of negative political messages that might have been hidden between the lines or expressed via rogue discordant notes. Even if they failed to detect such covert criticisms, they still had to be alert to the slightest hint of sarcasm or, perhaps, some oblique reference that constituted a cunning attack on the Party. When they had finally ascertained beyond the shadow of a doubt that there was no evidence of sarcastic intent or content, the possibility still remained that a coded hint in the text might in some way throw shade on the authorities. You see, sarcasm and snide allusions were powerful poisonous arrows, ones that could only ever be aimed at the enemy.

Even when The Leader was celebrated in the most fawning prose there was still a possibility that a phrase might be out of place or that the rote formulas of adulation had been ill-expressed. On top of that, you had to be particularly careful that the illustrative material you’d chosen to accompany the hosannahs or the design motifs were absolutely message-appropriate. To get something like that wrong would be seen as further proof that you “had a bad attitude” and simply weren’t up to the job.

Being from a “reactionary family” I was, of course, congenitally tainted. That meant that, when I did something that didn’t measure up, it was never regarded as being due to a lack of ability, rather it was because my “bad attitude” had been bred in the bone. A “bad attitude” reflected a flawed “ideological orientation” that, it only stood to reason, meant that I had, and was, a “political problem.”

If you happened to get caught up in the vicious cycle of their logic, you’d inevitably be punished if for no reason other than that you simply weren’t “people like us.” Instead, you were part of what they dubbed “the ongoing struggle with the enemy.” According to the rhetoric of the time, that meant you had to be “denounced, cast out, and stamped underfoot into eternal submission.” Such hyperbolic overkill inevitably meant that anything you did, no matter how trivial, could become a major political problem, one that also demanded punishment for anyone else associated with the transgression. In fact, this remains the default mode of Communist rulership today and it can be deployed at a moment’s notice and in every case, just as it can be modified to suit all contingencies. In practical terms, this means that a Party functionary at any level in the system can accuse you of a political crime, frame you, and have you jailed or even eliminated. Over the decades, countless lives have been destroyed by local cadres who have simply exaggerated minor misdemeanors and turned them into major cases of “premeditated political rebellion.” Who knows how many brilliant minds or devoted hearts have been undone by the nebulous requirement that “revolution must erupt in the depths of your soul like a spiritual atom bomb” [as Mao’s fawning courtier Lin Biao declared of Mao Zedong Thought in the early stage of the Cultural Revolution]?

Over the past 40 years [since the dawn of the era of economic reform in 1978], although China has enjoyed periods of relative liberalization, these have been matched by equally harsh political clampdowns. In the case of 1989, it resulted in tanks being sent into the streets of Beijing and the People’s Liberation Army firing on student protesters. Since then, politically things have been on a generally downward trend with the result that, today, we find ourselves in a suffocating iron cage, one that looks increasingly similar to that of the Mao era. That is why the nerves of publishers and editors like you are shot and why you find yourselves frozen in crippled hesitation. Today, the state of censorship in China is the worst it’s been since 1978. From the moment an idea takes shape in the mind of a writer right up to the time that, after a long and drawn out gestation, a book or article actually appears in print, it is more likely than not that it has been completely eviscerated, or distorted beyond recognition.

If we put the issue of self-censorship to one side for the moment, you as editors know all too well that when a manuscript is finally accepted for publication an author will have to deal with the following:

- An initial stage of pruning at the hands of the designated editor, something that invariably results in a slew of cuts and changes; following which

- The head of the editorial department will review the manuscript along with the suggested alterations, adding another round of nitpicking in the process; after which

- An external editor will go over it all again with the equivalent of an ideological magnifying glass; before,

- A final round of oversight and editing takes place at the hands of the editor-in-chief and the head of the publishing house, both of whom will examine the text with their acute, microscopic vision.

At any point in the process, the General Administration of Press and Publication may call the manuscript in for a “spot check.” Then there’s the Ministry of Education to think of. It has oversight over all of the academic publications produced by the universities in its bailiwick. The ministry has its own dedicated censorship committees empowered to carry out further “spot checks” relating to any topic, theme, or work that falls within its particular purview. Its paraphernalia is not limited to the editorial magnifying glasses and microscopes mentioned above, for it is able to marshal the equivalent of radio telescopes and night-vision goggles.

It’s said that these new dedicated censorship committees are made up of veteran propaganda cadres who have been invited out of retirement so that they can bring their long years of experience as cultural assassins to the task of keeping today’s academics in line. It is also observed that these revivified hacks pursue their duties with the ruthless energy of voracious ideological zombies. Are these the new “Experts”? Or should they be seen as rank “Outsiders”? [Note: Xi Jinping has revived the Mao-era requirement that academics, scientists, and professionals of all kinds be “Both Red and Expert” (又紅又專), that is, first and foremost they must study and internalize Party ideology so they can become “Red,” while constantly striving to excel in their particular fields of expertise, that is to be “Expert.” In the 1950s, academics and intellectuals decried these political invigilators as unqualified “Outsiders.”] There are numerous stories about the absurdity of this situation, and things are said to be in quite a mess. Of course, I can’t help feeling some sympathy for editors who are constantly being dragged over the coals and for all the stressed-out authors. However, the real victims of this renewed cultural hooliganism are the Chinese people and our nation as a whole.

Political interference of the kind I’ve described here both reflects and licenses an unlimited expansion of power as well as constant new rounds of wasteful “ideological rent-setting.” The thought-police enjoy extraordinary latitude and the most powerful of them all are the heads of what are known as the “Departments of Periodical Publication” [which are constituted under the Party’s central and local Publicity Departments and have oversight over all academic journal publication]. These people have a bloated sense of entitlement as well as extraordinary power. They chair virtually every meeting related to publishing and feel free to pontificate on whatever the subject under discussion happens to be, no matter how clueless they are. Although they merely mouth the latest Party nostrums in their frequent key-note addresses, they are nonetheless invited to attend every event and occasion and they are showered with gifts. They travel hither and yon on the public purse and enjoy the scenic spots of the nation, all in the guise of undertaking official duties. They also put the squeeze on their underlings and rake in the ill-gotten rewards of cloaked corruption. So, let me ask you this: Would any of them ever miss a banquet? How can they get away with all of this? How in Heaven’s name can this be happening? But, of course, the answer is simple: they are both wholesalers and retailers who enjoy a monopoly right over “The Truth.”

As you all know, editors-in-chief have a habit of treating both aspiring young writers as well as established authors anxious for their patronage with particular hauteur. Now witness how these same editors fawn over and cower before the all-powerful propaganda bureaucrats. They are little better than lap dogs and submissive curs. The relationship between these empowered ideological bosses and the editors disgusts me. They perform for each other in a way that reflects an unspoken complicity and a kind of self-serving magnanimity. It’s people like this who prosper in particular under a regime of systemic censorship.

Even though everyone in the publishing industry is a victim of the system as a whole, most of them also collaborate with and profit from censorship itself. Ultimately, no one is an innocent bystander.

- First, as for the victims of the system: every publisher, including those who only produce academic journals, relies for their continued existence on the propaganda organs of the Party-state.

- Then, it is all but impossible to start a new publishing enterprise or publish a new journal outside the state system, including academia, which itself is dominated by the Communist Party.

- Also, it is now forbidden for anyone to set up a non-official newspaper or magazine. Even those that still manage to survive are subject to annual reviews during which their content is scanned and sample material is scrutinized.

- Editorial inspections are followed up by rounds of awareness training, formal interviews with editors, as well as exacting ways to ensure compliance, which include the imposition of miscellaneous levies and taxes. The upshot is that it’s all but impossible for quasi-independent operators to survive.

Editors and employees alike, regardless of their rank, age, or gender, now live in constant trepidation for they never know what might cause offense. When something does go wrong, at the very least they’ll be subjected to a damning formal reprimand circulated throughout the industry, along with a hefty fine. At worst, a publishing license will be revoked—the equivalent of a death sentence for the journal in question will be banned and all of its employees will lose their jobs and benefits. The mere possibility of this scares everyone into compliance.

This kind of top-down pressure means that individual writers end up bearing the brunt of it all, the result of which is that they end up as the best censors of their own work. A system that keeps people in check like this guarantees that only the most irredeemably mediocre works gets published.

Friends, you’ve seen the results for yourselves and you know that the stuff being churned out by academic journals these days is second-rate at best. The smart operators who have given up their editorial independence and act as the handmaidens within the heavily policed publishing industry are also willing to exploit writers for profit. Since the government controls the certification of all publications, publishers avail themselves of their near-monopoly-control over an industry which enjoys constant and high demand. The censors and publishers benefit from artificial shortages created by the system that they control. So what they do produce is like food during a famine year, drinking water in the desert, or a vaccine during the plague. For their part, academics have to deal with a system based on the principle of publish or perish, one that is even more onerous in the case of younger scholars. That’s why publishers like you now find yourselves in a highly advantageous position.

Of course, there’s no dearth of stuff being published: such-and-such a bureau chief or director, no matter how artless their poetry or risible their prose, can always get their underlings to ghostwrite reams of material that appears regardless of quality. Some characters with impressive official titles actually have the wherewithal to instruct publishing houses to produce their books; the key to the whole operation is the magical word “power.” Others allocate state subsidies so they can be published, enabling the publisher to make a killing no matter how the book sells. Here, the key to the whole operation is that other magical word, “money.” Why, they might even celebrate some provincial prison governor for churning out a veritable library of “academic works,” even though the fellow is a renowned booze-soaked bureaucrat. Nowadays “productivity” of this kind is commonplace. In an environment in which systemic corruption is the leading ideology, those who benefit the most are the same people who are also victims of the system.

Censoring the Self

As a systemic form of coercion underwritten by a pervasive propaganda apparatus, censorship is embedded in every aspect of China’s cultural, educational, and public life. It is ever-vigilant and primed to pounce on, sequester, and eliminate aberrant information. The censoring system alone can truly represent The Truth; it holds sway over The Truth and it monopolizes The Truth. It is a system that has, in fact, become The Truth against which all else is measured. Nothing escapes its universal purview, be it thoughts lurking in the unique complexities of the human mind or the gossamer potential for our souls to delight in beauty or respond to sorrow. Why, even the scale of the sun and the brightness of the moon, the fluid movements of fish, the transformation of silkworms into moths, the irrepressible energy of children—all can and must be gauged and evaluated according to its Truth.

The system doesn’t stop with imposing its will from the outside, for it has long since inveigled its way into every heart, mind, and relationship. It penetrates your being in such a fashion that you are no longer aware of its discreet operations. It generates anxiety and excites terror in such subtle ways that you can never feel truly alone or be entirely at peace. It can do so because it inculcates an awareness of the danger of transgressing its “red lines.” Even when you just want to get on with life, it makes you hesitate before you dare take a step.

This is how all of you to whom I am addressing this letter—be you an editor or an author, or even one of the slavish intellectual courtiers riding high for the moment—are enmeshed in the system. Only someone like the jailer I mentioned above can really feel at ease. He’s a true player for he knows full well that all the books he’s “published” are just for show. He doesn’t even have to bother reading them.

The system reaches its apogee when the repression previously imposed externally has been completely internalized. By then, it has transformed our anxieties and fear of error into our most effective policemen. It’s what that familiar old expression “revolution erupting in the depths of the soul like a spiritual atom bomb” means in China today.

Aware that under no circumstances should we transgress the invisible barrier around us, we gag ourselves, deceive ourselves, repress ourselves so much that the habit of self-repression turns into a physiological addiction, an unconscious reflex in our everyday life.

The system knows all too well that people are hard-wired to want to try new things and question the world around them. It also knows that individual inspiration can be like gusts of wind under our pinions, raising our spirits to ever-new heights of human endeavor. That’s precisely why it focuses its attention on our innermost inspirations. When you open your heart and mind to its Truth, your soul must forswear all other possibilities and extirpate doubt. You need to banish independent hope and give up on the idea that you can truly think for yourself. As for all that talk about human potential or intellectual and cultural diversity—it can all go to hell! Under a regime such as this we are expected to live unremarkable lives, merely to survive and to shrink the rich array of life itself. They deny and forbid; they want to staunch and suffocate; they would rather throttle you than let you sing your song of freedom. To them, all swans are black and threatening. [Xi Jinping is obsessed with “black swan” events.] Over time, their invasive regime becomes second nature, or what the émigré Russian political philosopher Ivan Ilyin called a process by which “self-imposed compunction” (самопoнуждение) ends up as “psychological compunction” (психическое понуждение).

A soul thus imprisoned, a will thus perverted, leaves the heart open to an all-encompassing anxiety that can actually induce illness. It is as though we are always afraid of a police raid in the dead of night and fearful that some nameless punishment is awaiting us at dawn. Aware that under no circumstances should we transgress the invisible barrier around us, we gag ourselves, deceive ourselves, repress ourselves so much that the habit of self-repression turns into a physiological addiction, an unconscious reflex in our everyday life. The internalized coercion domesticates and disciplines us; their sadism becomes our masochism. We see the results all around us:

- The most daring will offer a pathetic gesture of resistance, though they’d never dare to confront the system;

- The vast majority of people become canny operators. They ignore the realities of the Party-state and let off steam by decrying the backward nature of the Chinese national character. They offer feeble excuses about things and blame it on the overall state of the civilization. At best, these people add a pinch of MSG to this Chicken Soup for the Soul; and,

- The most deplorable are the people who simper and hang around the entrance of the Ministry of Truth in the hope of being thrown some scraps.

This all-embracing culture of censorship dominates the country in two ways:

- First, there’s the brainwashing—a constant stream of distorting propaganda, brazen lies as well as the relentless banning of knowledge—starting at birth. It’s extraordinarily effective in darkening the windows of the soul; and,

- Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, is the salutary effect on the public of the harsh punishments meted out to anyone who dares transgress. Absurd charges are leveled at free-thinking people and, since the laws of the Party-state are based on a presumption of guilt, and because there’s a strict demarcation between “friend and enemy,” everyone is scared into compliance. After all, they know how merciless the system can be and they are further intimidated by the ever-present threat of guilt by association. As a result, the spirit surrenders and the mind shuts down.

. . . To survive you must submit, and submission is rewarded. Resistance, however, is futile and it leads to penury, or worse.

That’s why people readily chose to identify with the Leader, to go along with his peerless instructions and to applaud his sense of historical destiny. It’s also why people end up identifying with their oppressors and the thicket of rules and regulation that they impose. They learn to ingratiate themselves with the Great Storehouse of Truth and wait for the next clearance sale of discounted reality; it’s how people have grown accustomed to their straightjackets. In China, everyone is “a man in an iron mask”—though the catch is that each of us learns to forge the iron for our own mask.

What’s more, after people have internalized the self-censorship, the “victims” may all too readily repackage their ideas in the guise of patriotism or political realism so they can hawk them to the official media; they may even end up defending the official line or celebrating the leadership. Such illusory “self-realization” is like a pas de deux between the power holders and their subjects. The Internet age allows for an empire of illusion in which a welter of mindless entertainment distracts everyone from matters of substance.

Everywhere we see the kinds of “cultural courtiers” that the Hungarian dissident writer Miklós Haraszti described [in his 1988 book The Velvet Prison: Artists Under State Socialism] when talking about Bertolt Brecht [a renowned leftist playwright who had worked in Hollywood; remained silent about the Soviet purges, was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1954, and ended up in East Germany]. We all adjust and become ideological minions. As Haraszti says, “The state need not enforce obedience when everyone has learned to police himself.” We adapt and become executive engineers in the system or, worse, mere filing clerks. The huge machine spins on regardless like a whirligig. It doesn’t require real authors or editors; in fact, both the author and the editor are dead, and the only books produced are little better than user’s manuals. Meanwhile, the thought police continue to prowl with handcuffs and shackles at the ready. The only individual with real volition is those few men and women like that Dopey Doughy Autocrat. Although in reality, they too, my friends, are brain-dead creatures in this stark ideological age.

In our Velvet Prison, Alexander Solzhenitsyn could have been appointed president of the Writers’ Union. [And, as Haraszti goes on to say in The Velvet Prison: “. . . given time. And then no one would have written The Gulag Archipelago; and if someone had, Solzhenitsyn would have voted for his expulsion.”]

So this is what they mean when people talk about this being the Promised Land!

Before, I had been a P.O.W. in China’s Velvet Prison, nowadays I’m just a common criminal.

Intoxicated Together at the Cup of Tyranny

Hasn’t the present situation come about in part because for far too long we have grown accustomed to accepting the outrageous fortune meted out to us? Have we not chosen to make intellectual eunuchs of ourselves and drunk deep of the cup of humiliation? Through our compliance haven’t we encouraged the errant behavior of our oppressors? Are we not conjoined in a mutually reinforcing cycle that encourages their belief that “all things are lawful for me” [a line from 1 Corinthians 6: 12]?

My friends, it is a truism to say that, in certain respects, all tyrannies and all tyrants are empowered by the slavishness of their subjects. Although Agamemnon famously declared [in that eponymous tragedy by Aeschylus]: “no one freely takes the yoke of slavery.” The blindness, weakness, and cupidity of people, in particular the cunning of the so-called elites, all too often permits authoritarian behavior. [As the Marquis de Custine said of Russian autocracy:] “Sovereigns and subjects become intoxicated together at the cup of tyranny . . . Tyranny is the handiwork of nations, not the masterpiece of a single man.”

Also, as Ivan Ilyin observed, a person does not do evil in isolation, or merely because they are themselves thugs. Their victims have failed to resist the humiliations heaped upon them; indeed, they grow accustomed to thinking that repression is the natural order of things. Both the repressor and the repressed are corrupted by tyranny and, in turn, this leaves them both open to ever more extreme abuse. Only a greater good may possibly be able to resist the force of evil. Although by its very nature, when faced with implacable wickedness good all too often proves to be impotent. That is why some argue that evil can only be overcome by an even greater evil.

As I have said, tyranny maintains its sway by demanding the intellectual and spiritual castration of its subjects; by the ongoing and insidious corruption of people’s will to resist. The history of spiritual and intellectual independence, however, is not just a story about a few isolated individuals, for it also reflects a more general spirit of the age. Of course, there are always exceptionally independent people who appear in the world and their advent often encourages others to emulate them, to aim for a kind of transcendent sense of self. It is thereby that the few may have an impact on society as a whole. Those isolated individuals may thus inspire countless others who, through their support, further encourage more independent-minded individuals.

The crucially important link between such starkly independent individuals and those that they would inspire is the freedom of expression and a publishing industry that is its outlet. For these two encourage conversations and the evolution of public sociality; they allow for a form of resistance that shatters the silence imposed by autocracy. Freedom of expression and publishing are the very things that can bolster independence of the spirit; the republic of letters they foster nurtures in turn what can well flourish as a republic of ideas. But freedom exists only insofar as a space for public participation in politics exists in reality. In the process of participating in public power and the right to do so, citizens evolve, not merely as private individuals cloistered in solitary freedom, but as people who are both at home in their society and also part of the broader world. Their existence offers practical resistance to the kind of politics that is dominated by one family, one party, one faction, as well as all those things that would deny our commonality.

As Hannah Arendt has observed, “the raison d’être of politics is freedom, and its field of experience is action.” The key is that the individual self can find expression in the political arena, a place where the polis and the unique individual are at one. Private life, the retreat into an inward space, may allow for an inner freedom that lets people escape from external coercion and feel free, but Arendt was of the view that the individual can only truly find expression in the public sphere. Only when the individual is engaged with social organization in such a way that reflects both political ideals and model aspiration can a meaningful and positive modern political environment become possible. That is, [to quote a scholar of Arendt’s work,] that “politics is a vehicle for people’s self-expression and collective endeavors within the framework of civic life.” It is through society, then, that the individual can embark on something new: the joy of beginning something with one’s peers by means of debate, discussion, and the creation of “happiness.” These make it possible to share a stable world in common, one comprised of those public experiences in which all present can partake.

Thus, rather than the abstract dictum “I think therefore I am,” one’s existence is expressed through engagement with and action within the public arena. This allows for “my thinking” to be part of everyone else’s possibility. . . What then of the perpendicular pronoun “I”? According to my understanding, friends, that is existence itself. It is the “human spirit” that is truly imperishable. It is from this perspective that we can best appreciate what Arendt said about “rational truth” and “factual truth,” the roundedness of the former allowing it to outlast the latter.

Taking it a step further, I affirm that freedom can only truly be realized when equality is a universal value. Equality in turn proscribes excessive freedom—the dangers inherent in excessive equality can indirectly undermine freedom. The two are inextricably bound together.

China is still in the throws of monumental changes that require a great deal from all of us, in particular a collective refusal to be slaves. The situation brings to mind the Japanese novelist Kawabata Yasunari’s view that a true artist doesn’t simply appear out of nowhere, “they are a blossom that unfolds in the wake of generations of cultural ancestors.” What counts most is to remain steadfast in protecting every advance that has been made; what matters is allowing every work we produce to be available to all. Only through accumulated effort and wisdom can our joint endeavors over time irrigate the flowers of freedom so they may burst into boisterous blooms.

It’s been so long since any of us met. I wonder if you share these hopeful sentiments?

It’s been a long day and I’m coming to the end of what I wanted to say to you. Rising from my desk, I turn away from the window: I’m afraid that the setting sun will only serve to make my heartache all the more unbearable. Of late, I’ve really started to feel my age; it’s as though I’ve become an old man who has witnessed the passing cavalcade. But, then again, I’m nearly 60 and the season of decline is upon me.

The years ahead may pass peaceably enough. I may, as the old poem says, well enjoy “a dwelling with a hibiscus fence, plum trees growing by the stone steps on which to welcome the distant mountains and listen to the orioles.” But the rush of blood in my veins still denies me such placid vistas; my heart races yet and my mind is ill at ease. No matter how much I commune with the past, I still dwell constantly in present-day realities. My mood may exalt the lyrical, but it is a poetry that speaks of the awe of engaging with the prosaic. As the past swirls around me, my burning concerns are for the here and now. What does the future hold in store?—the unknown, sober resignation, and melancholy.

What, then, is to be done? Let us sing and dance:

“The support for the aging sage is

Not philosophical inquiry, but a walking stick from an ancient tribe

Encrusted with patterns that blur as he waves it in the air“You can hear the phoenix’s call long after that tribe disappeared and

Joined the civilized world, busy directing his disciples and pointing out the faults of society

Still capable of changing shape, suddenly one day dissolving in the flowing water”[— from the poem “Walking Stick for a Different Age” (“異代手杖記”), by Wang Ao (王敖)]

But I am no sage. I am a solitary old man and but part of the vast stream of becoming. All I have is my collection of poems in hand; they are my crutch. In the darkness beyond, there is sure to be a tribe whose numbers will swell; there, too, the phoenix will sing and the golden snake dance. Perhaps one may find that idyllic scene described in the ancient Book of Songs:

“There is a young lady like a gem

how well the black robes will befit her;

There too is a young lady with thoughts natural to the spring

a fine gentleman would lead her astray.”

Where might that be? Far from here, of that I am sure. How might one get there? By traveling the course and by forging the way. This brings to mind those verses in The Bible:

“And now, behold, I go bound in the spirit unto Jerusalem, not knowing the things that shall befall me there:

“Save that the Holy Ghost witnesseth in every city, saying that bonds and afflictions abide me.

“But none of these things move me, neither count I my life dear unto myself, so that I might finish my course with joy.”

My collected poems are banned, so, for the moment, there is no way that I can “finish my course with joy.”

“The Minor Cold,” The Gengzi Lunar Year

January 5, 2021, at dusk by the Old River Bed

***

Source:

- Xu Zhangrun, A Letter to My Editors and to China’s Censors 許章潤《致知編輯同》, ChinaFile on 18 May 2021.

***

Chinese Text:

致知編輯同人

許章潤

《庚子十劄》之八

一

如是我聞,平生交遊,除開師生,便是諸君。師生蔚為家園,諸君是家園的院子,她們和親情友愛合起來,組成了完整的家園,讓人生有了屏障,也畫地為牢。家中靜坐冥思,院中小徑徘徊,裏外連通,間架豁朗,透氣清明。天氣晴好的日子裡,要是還能望見遠山,或者踟躕於小街拐彎處,在微風蕩漾青磚院牆上藤蘿披掛如雨時發會兒呆,那該多麼愜意。

也許,院牆裡佳人如玉,正凝眸賞花,一霎時,落葉驚心,還不趕緊緩步輕聲。

當今之勢,做個教書匠,寫字作文,既是一己之私,也是職務之公,因而總想發表,總須發表,於是便聯絡於諸位,有求於諸位,而打交道,不得不打交道了。奈何因我之故,三年來漸行漸遠,此時此刻,竟至於悉數再無往來,音消響絕,也是諸君。此前同事早無來往,學界亦已主動將我逐出,這再加上出版編輯同人一去無音訊,便頓感窒礙,徬彿冬日裡暮色蒼然,踟躕於北國塵霾籠罩、噪聲轟隆的街道,雖人影瞳瞳,而人煙稀少矣。

許多年裡,承蒙諸君定期不定期寄贈書刊,這兩年漸漸少了,而今全無,雖說小事一樁,但好像心中還是有那麼一丁點兒失落感呢。過去收到贈閱的書刊多了,每覺累贅,甚而不勝其煩,而幾十年裡,書齋、圖書館和教室三點一線的生居作息早成規律,如今失去教室,又進不了任何圖書館,再也見不到「新刊速遞」,只靠家中有限藏書餵養,便覺得徬彿無所依徬,因而更感窒息。有時進城逛書店,看到陳列架上舊友新著,新人舊籍,洋洋灑灑,巍巍煌煌,在為他們欣慰的同時,難免爲自己連名字都不準見諸字紙的遭際心酸,迴響腦海的便是寅老的感喟,所謂「蓋棺有日,出版無期」。

怎麼辦呢?終於又能使用微信了。現在的中文微信公號,提供了許多便利,天涯海角若比鄰,乃不時掃描公號信息,盡量追蹤學界動態,勉力跟隨,聊以自慰。看到昔日學界友朋,以及成功學人商賈與退休高官,在此地講論辯學,於彼處致思敘事,更兼悠遊名山大川,他們的進路學理,他們的音容笑貌,乃至於他們的癖好偏向,宛在目前,便總是要打開看看聽聽,這彷彿另外一個世界的景象,庶幾乎算是從院子裡溜達到大街上去了。「有匪君子,文質彬彬」,哪怕人世再酷烈,也總得要留下點兒讀書種子,不能都象我這樣社死呀!畢竟,長期孤立的最好結果只能是平庸,或者,進一步平庸。這句話翻譯成大白話就是,伴隨著學術生涯終結與心靈萎頓的,是精神死亡。威爾士詩人R.S.托馬斯在《一首詩的誘惑》中曾經感詠:「誘惑是返回,與早年自己蒼白的靈魂幽會……那裡將恢復我們談話的詩意,在我們共同建立的世界餘燼之上」,概亦描摹我此刻的處境,而道盡我此刻的心境。

話題收回來。是啊,秦制之下,編輯和書商位處箝口惡政鋒芒所向之當口,各有自家的難處,都面臨著不得已,也都可能收到了種種明示暗示的指示,感受到處處直接間接的壓力。在一個書報審查嚴苛前無古人的極權國家,出版匪易,編事難為,令出書人步履蹣跚,讓寫書人如履薄冰。於是,不得不有求於人了。被求之人,本無感覺,這下便施施然儀態萬方了。從作者眼中來看,尤其是所謂官定「核心期刊」的大小主編們,佔據有利地形,手握重型武器,更是集萬千寵愛於一身,不少沐猴而冠,醜態百出。其中,貪婪無度的敗類,藉體制以逞威,挾公器以斂財,設關卡以騙色。至於吃吃喝喝,索煙要酒,安排旅遊,藉口講座潤資以行索賄之實,更是家常便飯,卻大言不慚:「做咱這個活兒,就是這點兒好處嘛。」以我寡聞,諸法學類雜誌,均有此種渣滓存焉。而且,越是核心,越發墮落。——此刻在下獨學無友,而又不見諸君久矣,每每念及,今夜想起,往事如煙,不免感喟潮湧,竟至於擴展為胡思亂想,而有上述怪力亂神,扯遠了,扯遠了,見諒。

此生幸運,往來過從的老少編輯,少勢利之輩,多平實之士,更不乏純良書生,可謂天地嘉惠,人和吉祥,不亦樂乎。本來,如同教書匠,這也是個冷清行當,招募吸引的多為素心男女。因而,此刻夜深,往事歷歷,諸君的音容笑貌,女娉男俊,老莊少諧,如在目前。過去為一字躊躇,交互釋證,彼此印證,乃至於爭執不下的情景,此刻想起,唯剩溫馨。既然已無資格和你們同桌舉杯嘆東風,亦無機緣再跟你們如往日般斟酌付梓瑣屑憐秋水,甚至於如一位編輯主任所言,「章潤已是負資產,能不沾邊最好就不要沾邊」,可在我一方,心中念念,不忍忘卻,便只好訴諸筆端,也只能託付字紙,任思緒紛飛,縱情感如悍馬脫繮。——暮年常想往事,心思沈浸故園,情絲溯蹤少小,用回憶連綴心意,藉心意安撫人生,於今昔往來中溫暖當下,冬天就不冷了,人雖然孤獨,但似乎也就不孤單了。而在我這邊,算是模擬性地小院徘徊,一番沈吟,幾度呢喃,操練一把巴黎左派所謂「對話就是相互捕獲」的腦力體操,以緩心腦衰竭。由此看來,我真的是一步跨進老年了,人生登頂,噫嘻。

當年俄國哲學家列夫·捨斯托夫年少輕狂,所作《無根據頌》天馬行空。格言體,形式不拘,正好盡性揮灑,任情瓢潑。其中一段,平靜而恣肆,是這樣説的:

做一個無可輓回的不幸者是一件可恥的事。一個無可輓回的不幸者往往得不到塵世法則的庇護。他與社會之間的所有關係,都被永遠打斷了。可是,由於或遲或早每個人都命定成為無可輓回的不幸者,所以,哲學所能說的最後一句話,就是孤獨。

在下非哲思中人,更非所謂「哲學工作者」,於上述文字只以生活經歷為憑,來理解,來品鑑,來消受,來感念。所得結論是,既然孤獨是「人類問題」,一個地球級別的問題,是我們的命運,我們的終極生存狀態,那就承受吧,反正無人得能倖免!大家碌碌,源於孤獨,為的是擺脫孤單。人心惶惶,本於生存,道出的卻是存在的孤絕本相。是啊,你看這浩茫宇宙,只有地球上有人,左無鄰捨,右缺街坊,多麼孤單,多麼寂寞,又是多麼無助。幸有其他動物作伴,可它們是生物鏈的一環,終究風月同天,而人獸異域,所謂「城邦之外」矣。在此,恰恰在此,好在有書,辛虧有書,書是人類發明用來消解孤獨的,書是用來抵抗躲避不開的孤獨的,書也常常是在孤獨中孕育出生的。可能,書還能夠讓我們抵抗孤獨而又倍感孤獨,因倍感孤獨而愈發求助於書,離不開書了。此刻在下致書諸君,也是書的事業,本來就打算將來輯集成書、留下一段心史的,則舞文弄墨,同樣旨在抵抗孤獨,徬彿也是言未盡而心已枯,神傷之際,倍感孤獨,又或,孤單。也許,萬千同樣的「不幸者」,異時異代,天南海北,將來有一天晴窗展卷,說不定讀來會心,醉後莞爾,而稍得排遣孤獨於片刻,再更深地陷入孤獨。就此刻我們而言,既然都是捨翁筆下的「不幸者」,那麼,歲聿雲暮,倩函托紙,聊作同病相憐,亦為抱團取暖也。——當然,此為一己我之心思,以一己之我為中心,由此四顧蒼茫,邁步尋覓,單相思,總不能強迫你們跟我熊抱呀。

二

諸位,說起來我也是個編輯呢。這不,少年章潤熱衷編輯板報牆報,畫兩筆,配個題圖邊花,把玩版式,變換字體和色彩。少年懵懂,任心緒翻飛;尺紙有限,而憧憬無邊。那埋首伏案的辛勞,焚膏繼晷的忘我,以專注填充暗夜的空寂,用疲憊驅散時光的戰慄,均發生在飢寒交迫的舞勺之年。——哈,我成熟得早啊。一燈如豆,心思沈斂,物我兩忘,醜惡的人世便退隱於無形,身心在匍匐傋僂中反得舒展。待到天光熹微,又將上學,遭受預料中的孤立、白眼和奚落,尤其是想到課堂上作為「反面教材」,突然冷不丁就被老師現場點名提將起來之赤裸裸、孤零零與無地自容,心裡反倒踟躕,腳步遂亦沈重。——許多年裡,上學成為每日的煉獄,而此生以教書匠始,以剝奪教師資格終,竟然幹的是陪童子讀書的勾當,造化弄人若此,亦堪訝異者也。

現在回頭一看,他們是老師,可又哪裏只是老師,或者,算哪門子老師呢!長時期裡,他們本身是「改造對象」,位列「臭老九」,慘遭羞辱,可他們同時又在規馴受教育者,許多時候,其實也是幫兇啊!此種受害人與加害者的角色錯位,特別是受害人的自我錯位,並非始於彼時彼地,實乃「人類問題」,道出的同樣是世界的悲劇性,彰顯了人際奴役關係的本相。所謂的社會與政治進步——如果進步依然是真實無欺的並且是可欲的概念,那麼,其旨意,其目標,正在於儘量減少並力爭掙脫奴役,指向那個可望而不可及的自由之境啊。人類天賦自由,一如生來便受奴役,深陷主奴枷鎖,所以自由在於衝決主奴關係,自作主宰,而有那個自我授受、自我正當化的自由意志之熠熠生輝也。正是這個自由意志,一種基於愛慾的生命意志,奔放熱烈,動感深沈,允許人類於灑掃應對的踐履中獲得神性,也就是具有超越性的人性,而令世界恰為人世。每個生命意志的獨立發育滋長,都生成於並意味著一種主體間性,從而賦予人世以人世性。此為基督時間裡對於不可救藥的人世勉力拯救的光明心態,也是激勵古典儒家入世精神的世界預設。否則,不如放達江湖,悠遊歲月,抑或,自劊以下,沈淪於酒色財氣、貪嗔痴執也。可縱便如此,它們也是掙脫主奴陷阱而又深陷其中的別樣形態,同樣基於一個委委屈屈的生命意志而已矣!

可能因此之故,我自做教師以後,呈示課程基本知識,梳理所涉基本理論,當然均不在話下。但授課不求提供結論,毋寧重在展示歧異觀點,陳列多元視角,讓受教者於比較中自己尋覓答案,一種可能與可欲的、而且必然是階段性的定見,概為一貫的態度。肯定會談自己的看法或者定見,但並不代表真理在握,原因就在於生怕形成智識屏障,妨礙受教者心靈自由馳騁。也許,這就是自由主義的教育觀,也是一種自由主義的致思方式吧。「唯一正確答案」可能出現在法庭,但無法壟斷於辟雍。此為思想王國與工科定律的差異所在,從而構成了此後兩種心智及其行動主體的社會政治適應性差異的精神原因。你可能會說,社會是所大學校,人世是個大染缸,一旦入身社會,不免人世浮沈,學校裡的教育便都還給老師了。

是的,學校只是提供一個初級產品,畢業後的生活靠自己,討生活的生活本身才是最佳教員,是我們的終生教員。但別忘了,怎麼討生活,如何生活得有意義,特別是如何看待生活的意義與人性的正邪,怎樣應對挫折,特別是如何應對一旦遭遇而且必然會遭遇的不公不義,包括同儕的傾扎、上司的為難、惡警的欺壓、路人無端的叱罵、面對社會苦難時的無力無助,當然,還有躲不了的體制的偏狹與歧視。——凡此種種,都需要一套社會政治觀念來應付,總不能只歸結爲「命運不濟」或者「鬼迷心竅」啊。縱便如此作結,其實也給予了一種社會政治觀念,而表達了一種社會政治觀念。這樣,人在江湖,無論長安得意馬蹄疾,抑或屋漏偏逢連夜雨,那時節,深蘊於心、蓄積腦海的一整套義理結構,平時隱而不彰,此刻便會砰然應急而出,替你拿方案,為你出主意。…..

而它們,正是它們,林林總總,千頭萬緒,可都是教育的結晶喲。遠的不說,什麼「垮掉的一代」、「民國範兒」或者「新保守主義的信徒」,自然都是特定時代教育與風尚的產兒,自己本身反過來又蔚為師範與風尚。謂余不信,諸位,你只抬頭看看今日眼面前正在上演的所謂「知青學術」與「知青政治」,便悉數一目瞭然矣。所以凱恩斯才會喟言,管理經濟的官僚們可能瞧不起經濟學教授們的理論,可他們此刻的所作所為正在實踐老師教授的那一套呢。是啊,每一個生都一樣,可每一次死都不一樣,當然別樣的死也是一種奢求。但縱便如此,哈,朋友,其實詩人早說了,「沒有什麼現在正在死去,今天的雲抄襲昨天的雲」。

又扯遠了,說我自己吧。因爲家庭成份不好,自己不及弱冠亦入另冊,早已棄絕於社會,因而,畫兩筆,編寫板報,此間幫閒,猶譬廢物利用,卻讓我獲享孤獨,憂傷而怔忡,無望複嚮往,堅定還徬徨。此後夢想考入美院深造而屢試不第,緣份在此,而命定如此,夢破之際,無情歲月早已千百遍輪迴於青石日晷。熬到青春當頭,缺衣少食,大學校園裡繼續這份勾當,卻已然無趣了,終至不合甩手。逮至上庠執鞭,公益私趣輻輳,徬彿一拍即合,終又重拾舊業,不得已,樂滋滋,遂略微遊走坊間。編刊叢書,搗鼓刊物,組稿約稿,小打小鬧,正所謂「知之不如好之,好之不如樂之」。主編《清華法學》,六載心血,著意於法意以明理為己任;組織《歷史法學》,十多年裡,孜孜在學術乃天下之公器。如此這般,既是作者,也是編者,兩邊做學徒,兩邊跑龍套。因而,對於兩邊的辛勞,雙方的為難,從心中靈光一現到爬格子蔚然成篇的崎嶇心路,自案頭文稿錯落至書香氤氳繚繞的困頓歷程,均有所體會,都能夠諒解。從而,有時候著急上火,而終至於半點兒火氣也無,原是不抱希望方懷指望,以微茫希望抵抗心底深處的絕望矣。

三

說來有意思,此生跟編事糾纏,自少及長,而中年出局,最先的感受是審查,最大的感受也是審查。層層疊疊的審查,深刻周納的審查,戰戰兢兢地審查,雞蛋裏挑骨頭地審查。不僅領導審查、群眾審查、讀者審查,事先審查、事後審查,例行審查、特別審查,常規審查、突擊審查,一般審查、專項審查,而且,首先是自我審查,神經質般地自我審查。有中生無,無中生有,荒腔走板,歇斯底里。若謂幾十年紅朝精神世界惡質荼毒,以何標格,當以箝口審查、扼殺思想為最矣。因為這個政體建立在謊言與暴力之上,只能倚恃謊言與暴力才能維持,所以必須封鎖信息,禁錮心靈,阻止一切可能讓真相露出水面的自由思想,堵塞一切揭穿謊言、有助於接近真理的絲絲縫隙。這也是一切極權暴政的通則,東西皆然。

猶記編輯板報,中學生的玩鬧兒,不外照葫蘆畫瓢,但文稿與配圖,卻也要班長和學習委員、宣傳委員審查,老師再審,最後班主任定稿,生怕出現一星半點兒「問題」。有時候甚至會讓班級小組長參與審查,請其他同學,如積極份子,從旁監督。「問題」者何?政治問題也。紅朝政治,說起來花哨,講起來冠冕堂皇,總是大言儻儻,其實核心就是領袖的「偉光正」,一心著意於黑白分明的敵我意識和同仇敵愾的敵我立場,尤其是「對敵人如秋風掃落葉」,在此不得出現一星半點兒差池,也絕不容忍任何模稜兩可與含混不清。因而,「惡攻」雖無,但不可不防「影射」,字裡行間的弦外之音。「影射」沒有,卻須嚴查譏諷,指桑罵槐的所指與能指。明確的譏諷雖無,但隱蔽的暗嘲必防。譏諷與暗嘲是投槍匕首,是明槍暗箭,只針對敵人,也必須投向敵人。可縱便歌頌,若措辭不當,或者配圖與紋飾不妥,也是「態度問題」,而非「水平問題」。家庭成份不好,本人「政治上有污點」,則「水平問題」就是「態度問題」,而「態度問題」就是「立場問題」,也就是「政治問題」。一旦歸入此檔,懲罰臨頭,則屬於「敵我矛盾」,打倒在地,再踏上一隻腳,永世不得翻身也。所謂「上綱上線」,紅朝政治整人的殺手鐧,運用自如,伸縮之間,端看需要與否。只要拉此大旗作虎皮,一個基層幹部也能讓你坐班房掉腦袋的啊。多少冤假錯案,便發生於此層層審查「上綱上線」的顯隱發微的流程之中;無數文思心火,就被這「靈魂深處爆發革命」的重重誅心之論所無情澆滅。

晚近四十年,雖說時鬆時緊,乃至於坦克上街向學生開火,但總體趨向是日益趨緊,終至於今日之鐵桶一塊,幾近毛魔時代也。這才有大家神經緊繃,在審查與自我審查中蹣跚趑趄。若在四十年縱深比較,則此刻箝口為最,一本書稿或者一篇文稿,從作者心中起念,到變成鉛字,路途漫漫,更不用說胎死腹中,或者,強迫流產了。拋開自我審查,若果書稿幸蒙納入審核流程,則大致情形是:首先責編過濾一遍,刪刪減減。其次編輯室負責人再過濾一遍,挑挑撿撿。然後外審加入,拿著放大鏡。最後主管之主編與社長終審,擺上顯微鏡。期間,政府新聞出版主管機構還要「抽審」,教育部對於下屬大學出版和期刊,居然設立專門審查機構,同樣可以隨時抽審。他們手拿的不僅是放大鏡和顯微鏡,可能還有射電望遠鏡與紅外夜視鏡。據說一幫子立場堅定的離退休文宣老人「反聘」歸來,專職此活,人人火眼金睛,個個文章殺手,抽風般如同打了雞血。內行耶?外行乎?笑話多多,攪成一鍋粥,為難的是責編,揪心的是作者,而承受斯文掃地災難的是全體國民和整個國族。

尤有甚者,一旦權力介入,卻又不受限制,則設租尋租便為順水之舟。你看看那些主管機關的官員,包括什麼莫名其妙的「期刊處處長」,人人理直氣壯,個個頤指氣使。坐主賓席,開口咿呀,不知所云;致開幕詞,閉口哼唧,等因奉此。到處接受吃請饋贈,遊山玩水,乃至於索賂受賄。單問一句:他們哪天不在酒席上?!他們為何如此?他們為何竟能如此?答案是他們是壟斷真理的批發商和零售商。而平時對作者尤其是對有求於他們的年輕作者端架子甩臉子的主編大人們,在這個叫做莫名其妙的期刊處的處長面前,扮小獻媚,作乖巧狀,作香甜狀,作哈巴狀,而乖得如狗,甜得膩人,哈得噁心,卻又彼此心照不宣,落落大方,正為這個邪惡書報審查制度所導致的人格悲劇與精神破產之絕佳樣本也。

在此,編輯出版行業及其從業者既是受害者,又是同謀,還是受益者,他們並非全然無辜嘛。就受害一面而言,所有的出版機構,包括各類期刊在內,其運行,其生滅,尤其是出生,都掌控在黨政文宣部門手中。除開黨政機構,包括大學在內,你想辦個出版社或者期刊,難乎其難,難於上青天嘛!至於民間辦報辦刊,一律禁止,絕無可能。好不容易出生運行了,什麼年檢年審咯,什麼抽查抽驗咯,以及被培訓、被約談咯,形如雞毛令箭,例同苛捐雜稅,可謂社不聊生,刊不聊生。主編也好,編輯也罷,男女哆哆嗦嗦,老少戰戰兢兢,生怕出事。一旦有事,輕則通報罰款,重則撤職停業。如若取消執照,意味著判決刊物死刑,頓時一大家子飯碗沒了,看你怕不怕。於是,層層施壓,最後轉化成作者的自我審查,造就了普遍平庸。

朋友,看看所有官辦刊物,尤其是各類大學學報之普遍平庸,垃圾成堆,便可一目瞭然矣。另一方面,就上述具體不良編輯來看,他們是利用嚴格書報審查體制敲詐作者、從中漁利、不折不扣的同謀。國朝體制,因為實行書號刊號政府壟斷體制,嚴禁民辦出版社和刊物,致使出書難,發表難。出版社和期刊編輯,其中又主要是掌有一定行政資源的權力者,遂成緊俏物資和緊俏人物,如同災荒年月的糧食,如同沙漠裡的飲水,如同瘟疫當頭時的疫苗,如同光棍村裡的寡婦,在此出現了不折不扣的短缺經濟現象。而無論是出版發表,論公論私,都是學人的生存必需,尤其是剛出道的青年學人之必需。如此這般,便有求於他們了,他們就抖起來了。那邊廂,這個局長,那個主任,他們的爛詩爛文,他們令手下炮製的爛書,卻照出不誤也。有的是官職當頭,出版社奉命照出不誤,關鍵是個權字。有的是用公款補貼,出版社獲利照出不誤,利害在個錢字。有個省的監獄局長,十來年裡,居然一邊做官喝酒,一邊出版了二十七部「學術著作」。考諸古今中外,可有此等醜事?!因而,不妨說,惡政之下,除開那些什麼期刊處一類管制機構的雜七雜八,他們和他們,是唯一的受益者,也是自覺不自覺的加害者。

四

是的,審查是外力強制,意味著以高度組織化的國家暴力為後盾的龐大文宣機器,密織羅網,晝夜伺服,隨時準備張網捕獵。它們代表真理,高居於真理,也壟斷真理,而成唯一真理。個體的無限豐富性及其心智的多樣可能性,人類心靈見花落淚的顫顫巍巍,太陽的大小和月亮的明暗,魚兒游走的姿勢和蠶蛾脫繭的次數,一家生幾個孩子,都必須整齊劃一於這個真理,或者,真理的化身。外力強制不僅落諸人身,旁及親友,加諸一切社會關係,更且滲入人心,打進魂靈,讓你知所戒懼卻又常常摸不著頭腦。於是,叫你張惶,令你恐懼,為手足無措而整日價兒踹踹不安,因懼怕動輒得咎而左右為難、趑趄不前卻又不得不往前挪步。如此這般,所有的作者和編者,包括那些春風得意的御用文人在內,其實遭受的是審查與自我審查的內外夾擊。只有「監獄局長」坐待春風,身後書架上滿佈他的署名、可既非他所撰作、他也從來不看的書。

在此,審查的成功之處,也是它所追求的效能,就在於將外力強制轉化成施壓對象的內在狀態,讓你在戰戰兢兢中時刻不忘自我審查,所謂「靈魂深處爆發革命」。換言之,除了膜拜服膺那個真理或者真理的化身,接受他們關於真理的批發或者零售,你必須將心靈之門主動鎖閉,令一切疑慮和嘗試的衝動消弭殆盡,讓多樣性和豐富性見鬼去吧。而懷疑精神與嘗試衝動,他們和我們其實一樣知道,是人類心智的發動裝置,也是托舉人類精神展翅翱翔之疾風;對於多樣性和豐富性的容忍與追求,在拓展形而上學的可能性之際,其實做實的——如果不說改善提升的話——是生活世界存在主義生存狀況的真實性,而賦予淒涼人世中輾轉求生的我們——飲食男女,人之大慾存焉——以在世性也。無此在世性及其所賦予的在世感,我們便飄飄蕩蕩,我們雙腳緊縛大地卻居無定所,我們為油鹽柴米生活著而無親歷生命的歡愉。但是,就是不准,偏要堵塞,掐住那個想要引吭高歌的喉嚨,將所有的天鵝一律塗成黑色。至此,規訓成型,終於成型,而規馴並非從天而降,實則早已轉化為自我審查狀態,正是俄羅斯流亡哲學家伊萬·亞歷山德洛維奇·伊里因所言靈魂自我強制之「自我逼迫」самопoнуждение 與「心理逼迫」психическое понуждение。它們令心靈鎖閉,它們讓心志萎靡,它們逼迫著心魂顫慄,它們甚至會同時造成生理創傷,在時刻擔憂深夜警察破門而入、黎明懲罰自天而降的恐懼中,在步步提醒自己不可越雷池一步的警示心態下,自我束縛,自我欺騙,自我壓迫,乃至於讓自縛、自欺與自我壓迫,成為身體慣性,內化成心理需求,以及每一個無意識下意識的日常動作。因此,它是外在暴力強制所造成的自我暴力,也是一種他虐促成的自我心理暴虐現象也。其最佳者,至多敢不修邊幅,而怯於對強權怒目;中位者,雞賊兮兮,痛心疾首什麼國民性,悲天憫人於文明優劣,熬雞湯加味精;其下焉者,則匍匐於真理部的台階,等候著門裡往外扔骨頭呢。

在此,外在的強暴轉化為自我施暴,「自我逼迫」和「心理逼迫」之所以成為現實,不僅在於經年洗腦、累月宣教的意識形態灌輸、欺騙、公然說謊以及信息封鎖,凡此種種,厥功至偉。而且,更主要的是經由逾矩即罰,自由心證下的欲加之罪何患無詞,有罪推定,在敵我定性的格局中施行殘酷無情的鐵拳鎮壓,無數次殘酷無情的鎮壓之重複所造成的普遍的大眾恐懼,並且不惜廣泛株連,這才令心靈慢慢鎖閉,這才讓心智逐漸萎頓,從而,叫心志終於徹底繳械的。——服從就能活命,甚至擁有一切你想擁有的;抗命就是這樣的下場,你將一無所有,甚至連命也沒了。於是,認同領袖,認同領袖的精神導師位格和偉大抱負,認同暴政所劃定的一切條條框框,皈依匍匐在那個偉大真理倉庫的門口等候批發零售。緊身衣就這樣不知不覺地穿上身了,鐵面人的鐵面原是自己幫著戴上的。

尤有甚者,受害人經此內化,可能將實實在在的理念包裝成啟示,貼上現實主義和愛國主義的商標,然後在官媒兜售,實現對於既有政治的辯護,對於領袖的讚頌,也讓自己華麗轉型,挾風登場,造成虛幻的「自我實現」,恰為一種意識形態受害人轉身而為幫兇跟班之小步舞曲也。置身此刻網絡時代,它還加上了無情帝國的文化沙塵暴,以愚樂之奶嘴樂,成功轉移視線,消弭一切可能的、哪怕只是一絲一毫的懷疑。歲月靜好,原是一種多麼美好的寧怡狀態,平常日子的平常陽光,院子裡樹蔭下的餐布上疏影橫斜,一縷茶香裊裊,兩隻蜜蜂嗡嗡,就這樣不幸變成了殭屍的活命哲學。更不用說,此間閃爍著布萊希特式的「御用背後的個人意願」——如米克洛什· 哈拉茲蒂所言——之心眼兒。如此這般,大家變成了具備適應性和執行力的工程師,或者更糟,辦事員也。龐大機器飛速旋轉,作者死了,編者也死了,所有的圖書自然更是悉數成為工具使用說明書,依舊神氣活現的是手執真理寶典和手銬腳鐐的思想警察,唯一器宇軒昂的是那個思想警察所層層疊疊環繞著的腦中風的癡肥僭主。其實,他或者她,朋友,也是殉葬於這個意識形態的殭屍而已矣。此時此刻,相較而言,那個「天鵝絨監獄」,說不定能讓索爾仁尼琴當個作協主席呢,哈,簡直就是福地了。

在此,我曾經是戰俘,此刻是囚徒。

[The following section is not included in the translated text:

五

其實,朋友,這個叫做「審查」的玩意兒,或者說文字獄,伴隨著文字而來,真所謂古已有之呢。如同立法旨在阻遏違法,預防違法,但卻同時意味著違法之必然性,違法乃是立法的伴生物或者副產品一般,這箝口審查的勾當,是文字本身惹來的。從秦始皇焚書坑儒,到康雍乾三朝喪心病狂株連十族,再至酷烈紅朝空前大規模戮心戮身,造成天下肅殺,惟我獨尊,全都圍繞著字紙縱橫,而意在扼殺人心。淫威之下,天下葸葸,士林隳頹,「避席畏聞文字獄,著書都為稻粱謀」。另一方面,敬天惜字,尊重文士,可憐文脈,乃至民間街巷顯豁專設「字庫」,洵為傳統,恰為反證。蓋因文字描摹世事,承載心事,溝通神鬼,牽連生死,是這地上的屬靈,是人心之通靈,非現世權力所能掌控,全然逸出了此在權威的範圍,這便令其懊惱,也可能讓它恐懼。肉身沈重,此在有限,可折疊扭曲,可囹圄囚禁,可斧鉞砍斫;唯獨心靈無形,奈何精神超越,其得出生入死,總能穿雲破霧。故而,欲控天下者必先控制其心靈,欲控萬眾心靈者必先控制其文字,一如欲滅其國者,必先滅其文字,這才有對於字紙之格外看守,而於字紙之傳播公示嚴防死守也。

於是,這便不能不說到人類是一個歷史的存在,也是政治的生物。歷史連結今古,載諸典籍,以董狐直筆為尚;政治施行於城邦,概以理念武裝制度,藉利益動員大眾,而必訴諸口號,宣示於典章。而無論直筆還是曲筆,理念還是利益,口號抑或典章,凡此皆需形諸字紙以宣示,必公示方始奏效。其間,褒貶臧否,揚抑月旦,史有史義,政歸政治,而世道自在,人心自現。而這就是思想,也就是人類精神之自我檢視,思想在公共對話中獲得了最可寶貴的反思性。換言之,思想天然具有公共性,也必以宣諭於眾之公開性,兌現自己的公共性,而獲得現實性,從而造就並進入公共空間和公共進程。

Translator’s reference: