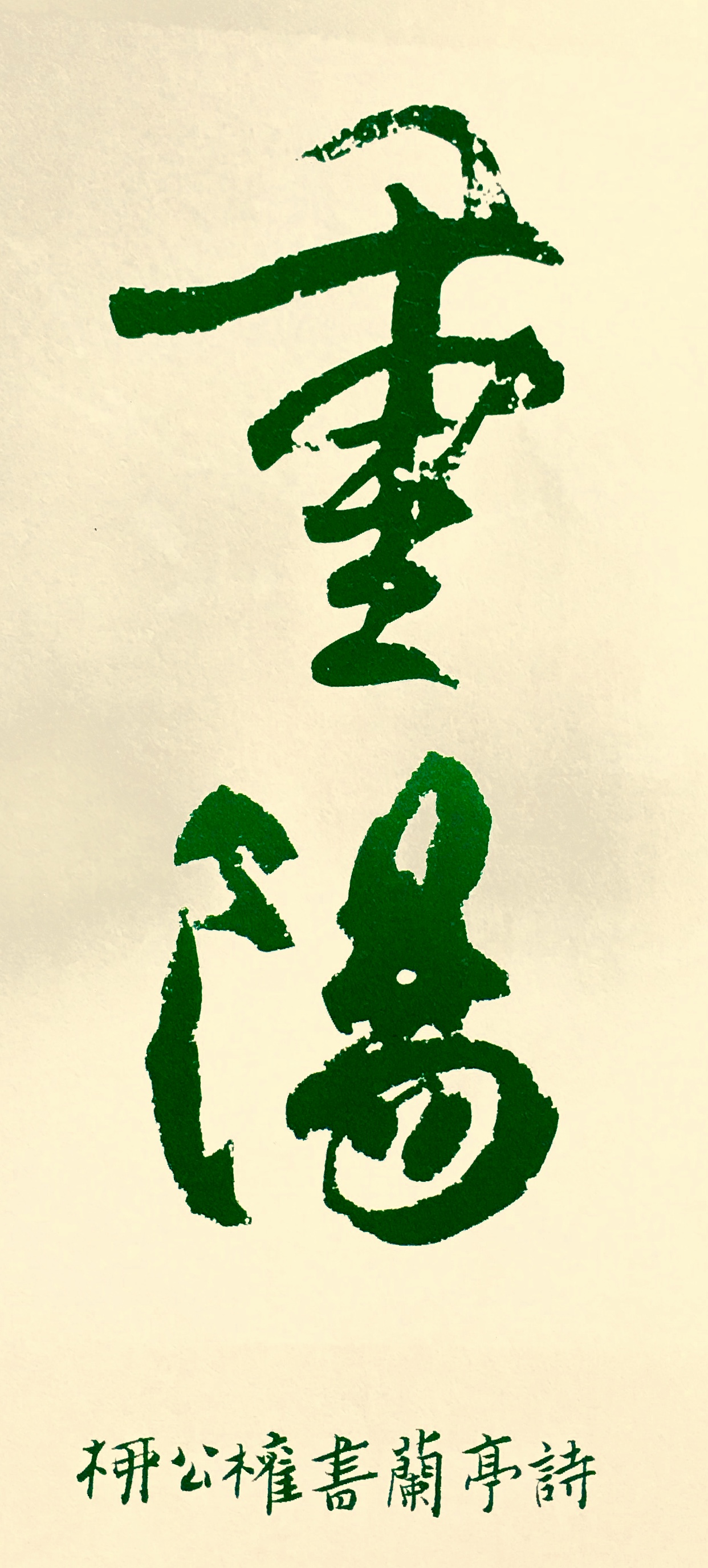

The 28th of October 2017 is the Ninth Day of the Ninth Month in the traditional lunar calendar 農曆九月初九. It marks the Double Ninth or Double Brightness Festival 重陽節. The Double Ninth, which follows shortly after the Harvest or Mid Autumn Festival 中秋節, is a celebration of the autumn, a season of late bounty, seasonal change, lingering beauty and finality.

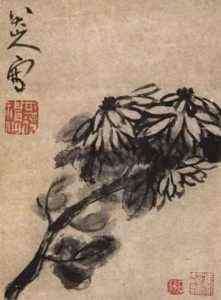

The Double Ninth is the autumnal counterpart to the Qingming Festival on the Eighth Day of the Third Month (see In the Shade 庇蔭 in New Sinology Jottings) which, apart from the commemoration of ancestors and sweeping of family graves, is also a time for spring outings (called 郊遊 or 踏青) to celebrate the season. Now, in the autumn once more it is time to climb a height to enjoy the spectacle of the season, to celebrate the passage of time with relatives and friends and to enjoy the fruits of the season, including dogwood berries 茱萸 and chrysanthemums 菊花, the petals of which were traditionally macerated in wine to encourage longevity (or at least to help numb the pain of existence); moreover, ‘nine’ 九 is a homophone for ‘long’ or ‘continuous’ 久. This is why the day is related to long life and the agèd; it is also known as the Chrysanthemum Festival 菊花節.

Yellow Flowers

The chrysanthemum has been cultivated in what is known today as Henan province 河南省 since the Song dynasty: the northern Song (960 to 1127 CE) had its capital at Bianliang 汴梁 or 汴京, modern-day Kaifeng. In 1983, the authorities in Kaifeng named the chrysanthemum the city flower and declared the Double Ninth to be the Chrysanthemum Cultural Festival. But the flower has older, and more ethereal, associations.

The recluse-poet Tao Yuanming (陶淵明 or 陶潛, 365–427 CE) has long been celebrated for his association with the chrysanthemum. A number of his poems are among the most often quoted, and over-interpreted, in the literary tradition. Famed for having given up service to the state for a life of leisure, writing, drinking, and occasional agricultural pursuits, Tao Yuanming is the archetype of a man who has rejected the onerous demands of the day to pursue instead the cultivation of the self. This quest for quietude, one also tinged with worldly concerns and fears, is recorded in poems that, for over 1600 years, have inspired artists and writers alike.

Even today, some who are encumbered by the demands of work, family and a myriad of obligations may think they are but ‘recluses at court’ 朝隱, biding their time in onerous employment in the hope of one day seeking out greener pastures. Others sidelined by political fate may strike a superior pose and pretend regardless to be otherworldly aesthetes while all the time yearning for a place in the hierarchy of the state; it is a mindset summed up in the expression ‘although one may physically be in the mountains, the heart is obsessed with the court’ 人在山林心在朝.

In our commemoration of the Double Ninth Festival we recall Tao Yuanming, as well as the modern artist Feng Zikai (豐子愷, 1897-1975) whose retreat from the chaotic world of 1930s was in part inspired by the ancient poet.

Deathly Air

The autumn also signifies decline and the approach of winter, the end of the year. In dynastic China executions — referred to in the expression ‘beheadings following autumn’ 秋後問斬 — were carried out as the season came to an end and winter approached; it was literally a time suffused with death 肅殺之氣. In North China, with only one growing season that concluded with the autumn harvest, it was time to settle debts, or to seek a reckoning for perceived slights and injustices. The practice is neatly summed up in the expression 秋後算賬, ‘to settle scores after autumn [harvest]’. Settling scores has also been a major feature of Chinese revolutionary life. It was the case with the violent failure of the Autumn Harvest Uprising 秋收起義 in 1927 when landlords and local officials were murdered, and, in recent times, since Communist Party congresses are convened in October, it remains so today. Each congress sees byzantine behind-the-scenes maneuvering and cloaked political payback.

A Place for the Old

In the past, the Double Nine was also a time when parents and the elderly were to be accorded particular respect. In 1988, the Ninth Day of the Ninth Month was officially gazetted as ‘China Seniors’ Festival’ 中國老年節; the commemoration of the day was formally included in the new ‘Law for the Protection of the Rights and Interests of Elderly People’ 老年人權益保障法, which went into effect on 1 July 2013.

On the Double Ninth Festival of 2016, as the Communist Party-engineered groundswell of adulation for Xi Jinping, China’s primus inter pares, heaved upward, the state media extolled Xi’s ethos of ‘respecting the old’ 尊老. It was reported that the first article the leader published in the People’s Daily under his own name in December 1984 called for younger Party cadres to respect and support their seniors. One year later, on the eve of the Double Ninth Festival in 2017, Xi Jinping Thought now overshadowed the contributions of his elderly predecessors, Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao. Few people familiar with the machinations of Xi and his entitled generation of Red Successors will have been surprised by these developments. As for the Chairman of Everything, over thirty years ago he had expressed himself, and given voice to his ambition, in no uncertain terms:

Of course, when we promote ‘respect for the old’ among young and middle-aged cadres it does not mean that we are encouraging people simply to copy what the elders have done, or to be hesitate in finding new work methods and styles, or indeed be fearful of breaking new ground. 當然,提倡「尊老」決不是要中青年幹部只能對老幹部一味效法,全盤照搬,甚至比貓畫虎,去適應一些已經陳舊的工作形式和方法,不敢越雷池一步。

Younger cadres must utlise their strengths to pursue reform, to dare to innovate and rely on their devotion to the cause and the sweat of their brow to forge a path forward. 中青年幹部要敢於發揮自己的優勢,銳意改革,大膽創新,用心血和汗水,去開拓新局面,闖出成功路。

With no successor in sight, the not-so-young Chairman of Everything Xi, as head of the Communist Party is now also Chairman of Everyone (黨政軍民學), as well as Chairman of Everywhere (東南西北中). His omnivalence was formalised in the 2017 Party Constitution, revised on the eve of the Double Brightness Festival.

The Burden of Memory

New Sinology Jottings introduce readers to aspects of culture, history and politics that resonate with the modern world; at the same time, they (re)introduce works integral to the mytho-poetic realm of China. For some, such musings are fustian and irrelevant, an affront to today’s neophilia, a drag on the relentless urge to escape from the past. However, as Lu Xun observed in his habitually scathing manner: ‘you can’t leave the earth by simply tugging at your own hair’ 人不能拽著自己的頭髮離開地球. Our terrestrial musings point to more eternal moments.

In New Sinology Jottings we feature well-know works not to replicate the cliché-festooned echo chamber either of Chinese state culture or its mass media; rather, we do so in a way that may help readers contemplate the old with new eyes. The following poetic meditation on the Double Ninth offers our perspective on what A.R. Davis, a noted translator of Tao Yuanming, called ‘the burden of memory’ in Chinese culture.

As Official China continues a decades-long enterprise to delineate, codify and interpret the totality of Chinese cultural expression in terms of its dialectical materialist analysis of humanity, the sensibility of New Sinology — one that complicates and lauds the diversity of China’s multiverse — is more relevant than ever.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Ninth Day of the Ninth Month of the

Dingyou Year of the Rooster 2017

丁酉雞年九月初九重陽節

Gramercy Park, NYC

***

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to John Minford for permission to quote from David Hawkes’ The Songs of the South, as well as from The Story of the Stone. We are also grateful to John for translating two poems from the Tang dynasty on the theme of this festival, and for providing his version of Li Qingzhao’s Double Ninth ci-lyric.

Annie Ren has contributed to these reflections in many ways, in particular with the Crab-Flower Club’s chrysanthemum poems from The Story of the Stone; she has selected and translated material from Cai Yijiang on the novel, as well as having located A.R. Davis’ essay on poetry and the Double Ninth. Christina Sanderson suggested one of the passages from Wanggiyan Lincing’s Tracks in the Snow which she edited on the basis of the translation by Yang Tsung-han 楊宗翰, and Callum Smith helped with the layout.

Lois Conner introduced me to the Chrysanthemum Festival at the Longwood Gardens in Pennsylvania, and has allowed us to reproduce some of the work she made there, as well as providing an earlier photograph made at Lu Shan, Jiangxi province. Lois was also my host at Gramercy Park in New York, where I worked on this latest New Sinology Jotting.

In the mornings I drank the dew that fell from the magnolia:

At evening ate the petals that dropped from chrysanthemums.

朝飲木蘭之墜露兮,

夕餐秋之落英。

— Qu Yuan, ‘Encountering Sorrow’,

translated by David Hawkes

***

Contents

- Autumnal Lament

- The Origins of Double Ninth

- Two Tang Poems

- The Ninth of the Ninth in Old Peking

- On the Chrysanthemum

- Tao Yuanming Gazing at South Mountain

- Chrysanthemums in Kaifeng

- Double Brightness by Li Qingzhao

- Chrysanthemums in The Story of the Stone

- A Bannerman’s Double Ninth

- Two Poems by Mao Zedong

- An Impromptu Verse

- The Late-chrysanthemum Flower

- Pines and Chrysanthemums Remain

Autumnal Lament

悲哉秋之為氣也

Song Yu 宋玉

Alas for the breath of autumn!

Wan and drear:

flower and leaf fluttering fall and turn to decay;

Sad and lorn: as when on journey far

one climbs a hill and looks down

on the water to speed a returning friend;

Empty and vast: the skies are high and the air is cold;

Still and deep:

the streams have drunk full and the waters are clear.

Heartsick and sighing sore:

for the cold draws on and strikes into a man;

Distraught and disappointed:

leaving the old and to new places turning;

Afflicted:

the poor esquire has lost his office and his heart rebels;

Desolate:

on his long journey he rests with never a friend;

Melancholy:

he nurses a private sorrow… .

悲哉秋之為氣也。

蕭瑟兮草木搖落而變衰。

憭栗兮若遠行,

登山臨水兮送將歸。

泬寥兮天高而氣清;

寂漻兮收潦而水清。

憯淒增欷兮薄寒之中人。

愴怳懭悢兮去故而就新。

坎廩兮貧士失職而志不平。

廓落兮羈旅而無友生,

惆悵兮而私自憐。

— from Song Yu 宋玉 ‘Nine Changes’ 九辨,

translated by David Hawkes in The Songs of the South

The translator remarks that this is a

magnificent threnody to dying nature… . We encounter, perhaps for the first time (in Chinese poetry), a fully developed sense of … the pathos of natural objects, which was to be the theme of so much Chinese poetry throughout the ages.

The Origins of Double Ninth

By the last century of the Six Dynasties period of the Double Ninth Festival had been given a precise origin. The Xu Qixie ji 續齊諧集 of Wu Jun (吳均, 469-520) has the following account, widely accepted in popular tradition:

Huan Jing 桓景 of Runan 汝南 was a companion of Fei Changfang 費長房 in his studies for many years. Changfang once said to him: ‘On the ninth day of the ninth month there will be a great disaster on your household. You should hurry and order the persons of your household each to make Red bags, fill them with dogwood 茱萸 and hang them on their arms. If you climb a hill and drink chrysanthemum wine, this disaster can be dispelled.’ Jing did as he said, and with all his household climbed a hill. In the evening they returned home and saw that the field and dogs, the oxen and sheep had died violently, all at once. Changfang said: ‘They took your place.’ This is why men of the present day always on the Ninth Day climb a hill and drink chrysanthemum wine, and the women carry dogwood bags.

Wu Jun’s account which thus places the origin of the festival in the later Han period is no doubt apocryphal, but it brings in all the basic associations of the Double Ninth — dogwood, the climbing of a height, the drinking of chrysanthemum wine, and the idea of the preservation of life.

— A.R. Davis, ‘The Double Ninth Festival in Chinese Poetry: A Study of Variations Upon a Theme’, in Wen-lin: Studies in the Chinese Humanities, ed. Chow Tse-tsung, Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968, pp.45-46.

Two Tang Poems

Remembering my Brothers on Double Brightness

Wang Wei

Alone in a strange land,

More homesick than ever on this festive day,

While my brothers are carrying dogwood up the mountain,

Each of them a branch — and one branch missing.

九月九日憶山東兄弟

王維

獨在異鄉為異客,

每逢佳節倍思親。

遙知兄弟登高處,

遍插茱萸少一人。

— translated by John Minford, after Witter Bynner

***

Celebrating white chrysanthemum blooms

at a Double Brightness party

Bo Juyi

In the garden filled with rich chrysanthemum gold

Stands one solitary clump of frosty white blooms.

Even so at today’s gathering, mid the wine and song,

A white-haired old man is tasting the joys of youth.

重陽席上賦白菊

白居易

滿園花菊鬱金黃,

中有孤叢色似霜。

還似今朝歌酒席,

白頭翁入少年場。

— translated by John Minford

Ninth Day of the Ninth Month

燕京歲時記 · 九月九

The ninth day of the ninth month is called in Peking the Double Yang 重陽. [Note: The number nine is used to designate the unbroken, that is the yang or male, lines in the hexagram of the I Ching (Book of Changes), which is the reason why the ninth day of the ninth month should be called the Double Yang.]

On this day people of the Capital take a kettle and winecups, and go out to the suburbs to climb some high spot. In the south they go to such places as the Temple of Heavenly Peace 天寧寺, Joyful Pavilion 陶然亭, and the Dragon-claw Locust Tree 龍爪槐. In the north are such places as the Density of Trees Surrounding the Gate of Ji 薊門煙樹 and the Wall of Pure Metamorphosis 清淨化城. Farther away are the Eight Buddhist Temples in the Western Hills 西山八剎. Reciting poetry and drinking wine, roasting meat and distributing cakes — truly this is a time of joy. 京師謂重陽為九月九。每屆九月九日,則都人士提壺攜榼,出郭登高。南則在天寧寺、陶然亭、龍爪槐等處,北則薊門煙樹、清淨化城等處,遠則西山八剎等處。賦詩飲酒,烤肉分糕,洵一時之快事也。

Flower Cakes

There are two kinds of flower cakes. One of these is made of sugar and flower, with pressed dainty fruits inside, and may be in two or three layers. This is the best kind of flower cake. The other is a steamed cake, the top of which is dotted with dates and prunes, this being a cake of the second grade. Every year at Chongyang time the shops make these to be used at this festival. 花糕有二種:其一以糖麵為之,中夾細果,兩層三層不同,乃花糕之美者;其一蒸餅之上星星然綴以棗栗,乃糕之次者也。每屆重陽,市肆間預為製造以供用。

According to the Account of the [Yuan] Capital 析津志, the people of the Capital would make cakes on the ninth day of the ninth month out of flour and give presents of them of the occasion of the Chongyang festival. Also they would be shouted and vended along the streets in bamboo baskets, in the same way as today. Again, according to the [late-Ming] Summary of Sights in the Imperial Capital 帝京景物略, there used to be wheat-flour cakes, the surface of which was sprinkled with dates and prunes, called flower cakes. Cake shops would advertise these with a blue flag, and fathers and mothers would invite their married daughters to come to eat them (at the parental home), this being called the ‘festival for daughters’ 女兒節. 按,《析津志》:九月九日,都人以麵為糕,饋遺作重陽節,亦於闤闠中笟筴席叫賣,與今同。又《帝京景物略》:麵餅麵種棗栗星星然曰花糕。糕肆標綠旗。父母迎其女來食,曰女兒節。

But cake shops to-day do not have advertising flags, nor is there any of this inviting of the daughter to come home and eat. This goes to show the differences in customs. 今糕肆無標旗者,亦無迎女來食者。蓋風尚之不同也。

Chrysanthemum Hillocks 九花山子

The chrysanthemum is also called the ‘ninth flower’ (because it flowers during the ninth month). At every coming of the Chongyang festival rich and noble families take several hundred pots of chrysanthemums and place them on a framework high in front and low in the rear, in the middle of a large room, so that they look like a hill. These are called ‘chrysanthemum hillocks’, while when the four sides are raised to a point they are called ‘chrysanthemum pagodas’ 九花塔. 九花者,菊花也。每屆重陽,富貴之家以九花數百盆,架庋廣廈中,前軒後輊,望之若山,曰九花山子。四面堆積者曰九花塔。

Peking’s variety of chrysanthemums are extremely numerous. They are divided into stalks of last year and stalks of this year, course stalks and fine stalks. 蓋京師之菊種極繁。有陳秧、新秧、粗秧、細秧之別。[Here we offer the names of chrysanthemums listed in the text — Ed.:]

如蜜連環、銀紅針、桃花扇、方金印、老君眉、西施曉妝、瀟湘妃子、鵝翎管、米金管、燈草管、紫虎須、灰鶴翅、平沙落雁、杏林春燕、朝陽素、軟金素、青山蓋雪、硃砂蓋雪、白鶴臥雪、青蓮子、青河蓮、朱瓣湘蓮、玉池桃紅、玉筍長、玉樓春曉、寶剎浮圖、落紅萬點、泥金萬點、藕色霓裳、伽藍袈裟等,皆陳秧中之細種也。如大紅寶珠、金連環、金霞環、大金葵、滲金葵、金盤獻露、金毛獅子、金鳳翎、紫鳳舒翎、紫鳳雙疊、紫龍開爪、紫蟹爪、真紫鉤、徐家紫、黃鶴毛、鷺鶴毛、蒼龍須、蒼龍訓子、雲龍煥彩、二色蓮、三季秋荷、映日荷花、旱地金蓮、芙蓉秋豔、玉扇銀針、紫鬆針、水紅針、玉匙調羹、粉屏、白牡丹、紫牡丹、粉牡丹、星光在水、楓林落照、夕陽斜照、鴉背夕陽、曉天霞、藍翎九等,皆陳秧中之粗種也。如銀虎須、墨虎須、朱墨雙輝、金卷硃砂、金鳳含珠、鳳梧添線、漢宮春曉、浣花溪水、天半朱霞、秋水明霞、秋水芙蓉、漢皋解佩、二喬爭豔、天女散花、桃花人面、鳥爪仙人、黃鶴仙人、羔裘大夫、仙人掌、醉太白、南極仙翁、文經武緯、鳳管鸞笙、洋蝴蝶、羚羊掛角、香白梨、金如意、水晶如意、沉香貫珠、一斛珠、碧玉搔頭、黃繡球、珊瑚鉤、金帶風飄、慈雲點玉、慈雲萬點、柳線垂金、重陽居住等,皆新秧中之細種也。如金佛座、金鉤掛玉、金邊大紅、玉堂金馬、紫綬金章、紫袍金帶、紫電青霜、綠柳黃鸝、楊妃醉舞、西施粉、六郎面、墨麒麟、鸚哥抱子、蜜蜂窩、合家歡樂等,皆新秧中之粗種也。

This makes a total of one hundred and thirty-three kinds, all of which I remember. But for those who can think of them, there are still more than two hundred other kinds among these four classes. Some day when I have leisure, I certainly intend to compile a list of flowers. 共一百三十三種,皆予所記憶者。其餘新陳粗細之類,尚有二百餘種,他日得暇,當為黃花訂譜也。

Fruits and Foods of the Season

糟蟹、良鄉酒、鴨兒廣、柿子、山裏紅

At the Chongyang festival time, pickled crabs 糟蟹 eaten together with Liangxiang wine 良鄉酒 are very sweet and delicate. Liangxiang wine is produced in the district of Liangxiang (which is near Peking, west of the Marco Polo Bridge or Lugouqiao), but in recent times Peking itself has also been able to make it. Its taste is pure and rich, and when one drinks it one has a feeling of well-being. It only fears the heat, so that it cannot pass through the summer. ‘Duckling Yellow’ 鴨兒廣 are a kind of pear, shaped like a quince, and like the yellow of ducklings in colour … . Persimmons 柿子 and red hawthorns 山裏紅 have uses even more numerous and are both Peking products of the season. 重陽時以良鄉酒配糟蟹等而嘗之,最為甘美。良鄉酒者,本產於良鄉,近京師亦能造之。其味清醇,飲之舒暢,但畏熱不能過夏耳。鴨兒廣,梨屬,形如木瓜,色如鴨黃,廣者黃之轉音也。柿子、山裏紅,其用尤多,皆京師應序之物也。

According to the Jiyuanjisuoji, during the time when Taizu (1368-1398), founder of the Ming dynasty, was still obscure, he was once passing through Shengchai Cun, having already gone two days without food. Walking slowly alone, he reached a place which had once been some family’s garden. But now the wall was gone and the trees were hacked down, having been cut up for the fires of soldiers. His Majesty gave a sigh of sorrow, and paced slowly, looking about him the while. In the north-east corner was a single tree, the frost-bitten persimmons on which were just ripe. His Majesty took some and ate them, consuming ten until he reached repletion. Then, after yet grieving a long time, he went away. 按,《寄園寄所寄》:明太祖微時過剩柴村,已經二日不食矣,行漸伶仃。至一所,乃人家故園。垣缺樹雕,是兵火所戕者。帝悲歎之,緩步周視,東北隅有一樹霜柿正熟,帝取食之,食十枚便飽,又惆悵久之而去。

In the summer of the Yiwei year [1355], when he seized Taiping by means of Caishi, he passed here again, and found the tree still standing. His Majesty pointed it out, and described to his followers what had once taken place. Then he dismounted and wrapped the tree with a red robe saying: ‘I hereby invest you with the title “Marquis of Ice and Frost”.’ 乙未夏,帝拔採石,取太平,道經於此,樹猶在。帝指樹,以前事語左右,因下馬加之赤袍,曰:封爾為淩霜侯。

This was indeed a persimmon tree able to be of service to a ruler of men! And why then should the record of it be more fragmentary than the records of other things? For to have met this persimmon tree was good fortune indeed. 是柿曾有功於人主矣,則記之豈瑣瑣哉?他物之記,亦邀柿之幸也。

— from Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking,

as recorded in the Yanjing suishiji 燕京歲時記,

by Tun Li-Ch’en, translated and annotated by Derk Bodde,

Peip’ing: Henri Vetch, 1936, p.69ff.

Romanised words have been converted to Hanyu pinyin.

On the Chrysanthemum

Cao Pi 曹丕

曹丕與鐘繇書

The year goes, the months come. Suddenly it is again the ninth day of the ninth month. Nine is the number of the Light Force 陽, and day and month correspond with one another. Common people delight in its name and believe it appropriate to long life. Therefore on it they give banquets and meet together on heights. This month is in the pitch-pipes 無射; that is to say, of the mass of trees and many plants there are none which shoot from the ground and grow. 歲往月來,忽復九月九日。九為陽數,而日月並應,俗嘉其名,以為宜於長久,故以享宴高會。是月律中無射,言群木庶草,無有射地而生。

Yet the fragrant chrysanthemums abundantly bloom by themselves. If they did not contain the pure harmony of Heaven and Earth and embody the clear essence of fragrance, how could the do so? Therefore Qu Yuan grieved at his steadily growing old and thought of eating the fallen blossoms of the autumn chrysanthemums. For supporting the body and prolonging life nothing is as valuable as these. I respectfully offer a bunch to aid in the art of Pengzu 彭祖 [i.e., longevity]. 至於芳菊,紛然獨榮。非夫含乾坤之純和,體芬芳之淑氣,孰能如此。故屈平悲冉冉之將老,思飧秋菊之落英,輔體延年,莫斯之貴。謹奉一束,以助彭祖之術。

—Emperor Wen of Wei (Cao Pi 曹丕, 186-226) to Zhong You (鐘繇, 151-230),

translated by A.R. Davis.

Editor’s Note: Cao Pi was a member of a talented but notorious family. He plotted the end of the Eastern Han dynasty and proclaimed himself ruler of Wei 魏, one of the fractious Three Kingdoms in an era that ushered in centuries of political strife and social disorder. It is that world of anomie from which Tao Yuanming, as well as the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove, chose to withdraw. The political chicanery of the Cao’s lives on in present China, as does the ineffable state of those who would seek an untrammeled realm.

Tao Yuanming Gazing at South Mountain

…an Inspector was sent by the commanders to Tao’s district. Tao’s subordinates told him that he ought to tie his girdle and call on the Inspector. Tao said with a sigh: ‘I cannot for five pecks of rice bow before a country bumpkin.’ The same day he untied his seal-ribbon and gave up the post… . 郡遣督郵至,縣吏白應束帶見之,潛嘆曰:吾不能為五斗米折腰,拳拳事鄉里小人邪。義熙二年,解印去縣。

— from ‘Biography of Tao Yuanming’, c.488 CE, translated by A.R. Davis

***

The poetry of Tao Yuanming (Tao Qian, 365-427), a reclusive gentleman who quit his official post to live obscurely on a small private farm, is the classic body of writing on life in retirement. …

Tao had made a choice between political and social engagement on the one hand, and withdrawal and self-cultivation on the other. Though most lives, of course, are lived along the continuum between these poles, in traditional Chinese discourse engagement and withdrawal are seen as the two basic orientations for a thinking person. Confucian teachings encouraged the former course, looking after one’s family and serving society and the state. The choice of withdrawal, on the other hand, implied a preoccupation with more spiritual and abstract values: recluses dedicated themselves to philosophical or religious pursuits, artistic activities, and attunement to nature. Eccentric and independent, they turned their back on worldly concerns — advancement, honors, power, wealth, conventions of all sorts. Recluses might be faulted for self-indulgence and irresponsibility, but the reverberations of their personal virtue were a contribution, too; indeed, they might eclipse the deeds of statesmen and generals as a legacy to the world at large. Theirs was seen as, ultimately, the loftier way.

— Susan E. Nelson, ‘Revisiting the Eastern Fence:

Tao Qian’s Chrysanthemums’, Art Bulletin,

vol.lxxxiii, no.3 (September 2001): 440

***

I built my house near where others dwell,

And yet there is no clamor of carriages and horses..

You ask of me ‘How can this be so?’

‘When the heart is far the place of itself is distant.’

I pluck chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge,

And gaze afar towards the southern mountains.

The mountain air is fine at evening of the day

And flying birds return together homewards.

Within these things there is a hint of Truth,

But when I start to tell it, I cannot find the words.

結廬在人境,

而無車馬喧。

問君何能爾。

心遠地自偏。

採菊東籬下,

悠然見南山。

山氣日夕佳,

飛鳥相與還。

此中有真意,

欲辨已忘言。

***

At Leisure on the Ninth Day

九日閑居

When I was living in retirement, I delighted in the name of the Double Ninth. The autumn chrysanthemums filled my garden but I had no means of taking wine. So in want for it, I partook of the Ninth Day flowers and put my feelings into words. 余閑居,愛重九之名。秋菊盈園,而持醪靡由,空服九華,寄懷於言。

Life is short but desires are always many;

We men delight in living long.

The day and month come at due time;

Every common man delights in the day’s name.

The dews are chill, the genial breezes cease;

In the clear air the heavenly signs are bright.

Of the departed swallows not a shadow remains,

From the arriving geese there is abundance of noise.

Wine can drive out manifold cares,

Chrysanthemums may arrest declining years.

How is it with the rustic hut scholar?

in want, he watches the season passing.

The dusty cup shames the empty wine-jar;

The cold flowers vainly display themselves.

Adjusting my robe, alone I sing a song of leisure;

In my brooding arise deep feelings.

At rest, truly there are many joys:

My lingering is surely not without achievement?

世短意常多,

斯人樂久生。

日月依辰至,

舉俗愛其名。

露淒暄風息,

氣澈天象明。

往燕無遺影,

來雁有餘聲。

酒能祛百慮,

菊解制頹齡。

如何蓬廬士,

空視時運傾。

塵爵恥虛罍,

寒華徒自榮。

斂襟獨閒謠,

緬焉起深情。

棲遲固多娛,

淹留豈無成。

***

Written on the Ninth Day of the

Ninth Month of the Year Jiyou [409 CE]

己酉歲九月九日

Slowly, slowly,

the autumn draws to its close.

Cruelly cold

the wind congeals the dew.

Vines and grasses

will not be green again —

The trees in my garden

are withering forlorn.

The pure air

is cleansed of lingering lees

And mysteriously,

the Heaven’s realms are high.

Nothing is left

of the spent cicada’s song,

A flock of geese

goes crying down the sky.

The myriad transformations

unravel one another

And human life

how should it not be hard?

From ancient times

there was none but had to die,

Remembering this

scorches my very heart.

What is there I can do

to assuage this mood?

Only enjoy myself

drinking my unstrained wine.

I do not know

about a thousand years,

Rather let me make

this morning last forever.

靡靡秋已夕,

淒淒風露交。

蔓草不複榮,

園木空自凋。

清氣澄餘滓,

杳然天界高。

哀蟬無留響,

叢雁鳴雲霄。

萬化相尋繹,

人生豈不勞。

從古皆有冇,

念之中心焦。

何以稱我情。

濁酒且自陶。

千載非所知,

聊以永今朝。

— translated by William Acker

***

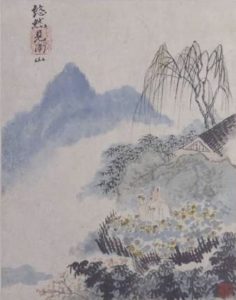

Su Shi’s Lu Shan

Su Shi (蘇軾, 蘇東坡, 1036-1101), a scholar-bureaucrat of the Song dynasty, and one of the great writers of his age, found solace in Tao Yuanming’s poetry when he was himself forced into exile. An unwilling recluse, Su nonetheless paid homage to Tao in a series of poems. He also wrote about what was even then an immortal line:

採菊東籬下,

悠然見南山。

He noted that rather than using ‘to look out towards’ 望, a purposeful contemplation, the poet had chosen ‘to catch sight of’ 見, a glancing and spontaneous poetic gaze. Su’s interpretation, and speculation about the line has been debated ever since.

Their most famous anachronistic, and accidental, collaboration, however, came about as a result of Lu Shan 廬山, the South Mountain itself and the place near where Tao lived in retirement. At the beginning of this section we quoted Tao Yuanming’s poem related to the mountain, we will end it with a famous quatrain by Su:

Written on the Wall at West Forest Temple

Su Shi

From the side, a whole range;

from the end, a single peak:

Far, near, high, low, no two parts alike.

Why can’t I tell the true shape of Lushan?

Because I myself am in the mountain.

題西林壁

蘇軾

橫看成嶺側成峰,

遠近高低各不同;

未識廬山真面目,

只緣身在此山中。

— translated by Burton Watson

The Temple of the Meeting of the Seas 海匯寺 faces Lake Poyang 鄱陽湖. Laid waste during the tumultuous years of the Xianfeng 咸豐 reign in the mid-nineteenth century, the temple was rebuilt in the Guangxu 光緒 era. The main temple building originally bore the words ‘Lotus Land and Sea City’ 蓮邦海城, the secondary building still carries the inscription ‘True Mien’ 真面目, words made famous by Su Dongpo’s poem quoted above. The Peaks of the Five Ancient Ones of Lushan looms behind the temple.

***

‘When the heart is far the place of itself is distant’ 心遠地自偏 — Tao Yuanming’s sentiment is in keeping with the spirit of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology. It accords also with the ethos of China Heritage as described in the essay On Heritage 遺.

As we will see below, the image and work of Tao Yuanming has also been used to excoriate those who would look beyond the ‘dusty world’ and reject service to the state. Others cloak themselves in the garb of the nonchalant recluse while devoting themselves to venal pursuits. None of this detracts from the Tao’s singular voice, which for those who have the ear to hear it is as resonant today as it was 1600 years ago.

Chrysanthemums in Kaifeng

An annual Chrysanthemum Festival 菊花節 (orignally called the Kaifeng Chrysanthemum Flower Show 開封菊花花會) has been held every October in Kaifeng, Henan province, since 1983.Floral displays are arranged at five local sites: Dragon Pavilion 龍亭, Iron Pagoda 鐵塔, Support the Dynasty Temple 大相國寺, Master Bao’s Temple 包公祠 and at the Platform of King Yu 禹王台.

As with other such promotional and marketing activities, the party-state works closely with local business as well as cultural and educational institutions to focus tourist attention, sponsorship opportunities and official largesse on the city. In the process, the local tradition of cultivating the delicate autumn flower, something that last flourished in the Northern Song dynasty some seven centuries ago, has been turned into a kitsch celebration of rococo-style flowers along with a debasing of literary and artistic traditions in a bid to attract ever more numbers of local and international tourists.

From 1982, a similar sorry fate has befallen the peony in Luoyang 洛阳, another city in Henan with a long dynastic history. Originally cultivated in the city during the Sui dynasty in the sixth century, in recent times the association between the city and the flower has been cemented in the form of the Luoyang Peony Cultural Festival 中國洛陽牡丹文化節, which is held every spring.

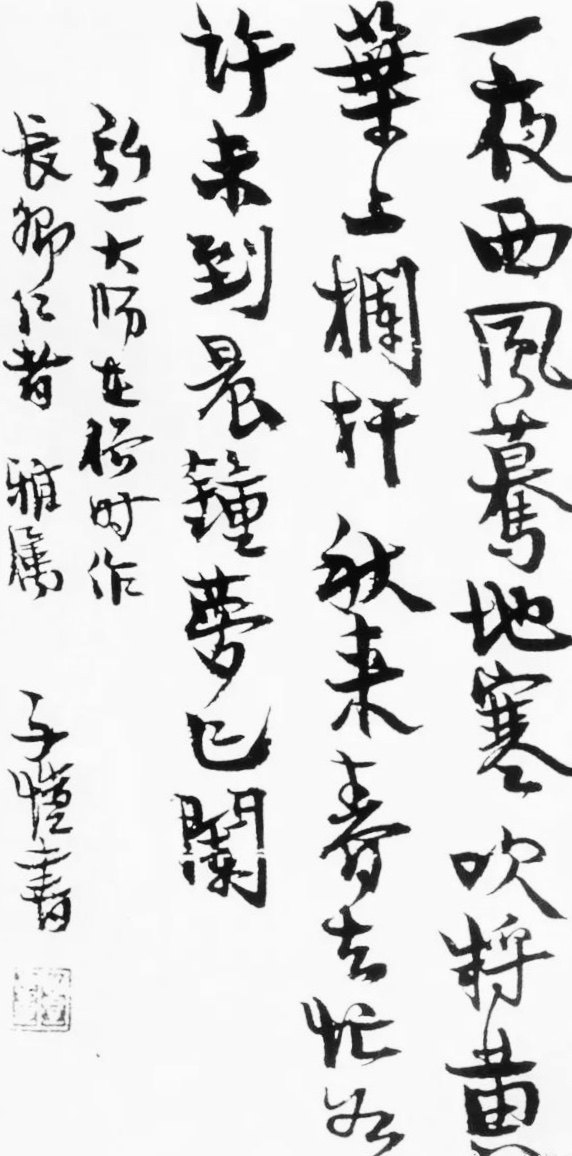

Double Brightness 重陽

Li Qingzhao 李清照

— to the tune Drunk in Flower Shadows 醉花陰

light mists and heavy cloud

a day of sorrow that would never end

jui-nao incense oozing

from the censer’s maw.

another fine festival

Double Brightness

come and gone

First chill of midnight steals

in my silken-netted cage

touches

my jade pillow

by the eastern hedge, wine in hand,

in the golden aftermath of dusk

I stood

perfume darkly blowing in my sleeve

Vain to deny grief:

See, when the west wind stirs the blind

this visage

than the golden flower more frail

薄霧濃雲愁永晝,

瑞腦消金獸。

佳節又重陽,

玉枕紗廚,

半夜涼初透。

東籬把酒黃昏後,

有暗香盈袖。

莫道不銷魂,

簾卷西風,

人比黃花瘦。

— translated by John Minford

As the translator notes:

The one specific reference in this poem is to the Double Brightness Festival. But there has never been any doubt in the minds of Chinese readers that Li Qingzhao is here expressing, in the oblique manner of the ci-lyric form her grief at separation from her husband. She uses the festival to counterpoint this grief, and in the second stanza conjures up the shade of Tao Yuanming and his famous ‘chrysanthemums under the eastern hedge’. Tao’s detachment and repose are in stark contrast to the poetess’ all-too-human emotion. That emotion is none the less potent for being so understated.

On one level, the whole poem can be read as the woman lyricist’s response to the Double Brightness tradition in poetry, of which Tao the Hermit was the founding father.

Chrysanthemums in The Story of the Stone

Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹

Two Episodes translated by David Hawkes

The inhabitants of Prospect Garden create the Crab-Flower Club 海棠詩社, the members of which are named after the buildings which they occupy in the garden. These two episodes, selected by the Stone scholar Annie Ren, are from chapters 37 and 38 of the novel. The English translation is from David Hawkes, The Story of the Stone, Volume II: The Crab-flower Club.

— The Editor

***

The poetry club, where the young residences of Prospect Garden can come together and compose verse to a set theme or rhyme, is similar to the kind the literary gatherings favoured by the Manchu aristocracy and Bannermen elite. For instance, [Aišin-Gioro 愛新覺羅] Duncheng 敦誠, a friend of the novel’s author, included pages of linked verse written by his circle of friends at drinking parties in his Writings from Four Pine Studio 四松堂集. Such literary games are a feature of The Story of the Stone; linked verse competitions appear twice [once in Chapter 50 and again in Chapter 76]. Cao Xueqin could easily have substituted the names of his friends with the names of his fictional characters.

The twelve chrysanthemum-themed poetic titles may be presented as having been invented by Bao-chai and Xiang-yun on a whim, however, a group of eight poems with almost identical titles can be found in the poetry collections of two members of the imperial clan: those of Yongen 永恩 and Yonghui 永㥣. In the discussions about poetry by the book’s characters, expressions such as ‘not letting the words harm the meaning’ and ‘samādhi’ 三昧 are also used in many Qing works on poetry. So, contrary to what the author calls ‘a faithful record of the females from my youth’ 閨閣昭傳, The Story of the Stone is actually a depiction of Qing men of letters.

— Cai Yijiang 蔡義江, An Explication of the Poetry in The Dream of the Red Chamber

紅樓夢詩詞曲賦全解, 香港中和出版社, 2017, 第235頁, translated by Annie Ren.

***

From Chaper 37

An ingenious arrangement enables Bao-chai

to settle the chrysanthemum poem titles

蘅蕪苑夜擬菊花題

‘Yes’ said Xiang-yun, without much conviction; but presently smiled as a new idea occurred to her. 湘雲只答應著,因笑道:

‘I’ve just thought of something. Yesterday’s theme was “White Crab-blossom”. The flower I’d like to write about is the chrysanthemum. Couldn’t we have “Chrysanthemums” as our theme for tomorrow?’ 我如今心裏想著,昨日作了海棠詩,我如今要作個菊花詩如何。

‘It is certainly a very seasonable one,’ said Bao-chai. ‘The trouble is that so many people have written about it before.’ 釵道:菊花倒也合景,只是前人作的太多了。

‘Yes,’ said Xiang-yun, ‘I suppose it is rather a hackneyed one.’ 湘雲道:我也是如此想著,恐怕落套。

Bao-chai thought for a bit. 寶釵想了一想,說道:

‘Unless of course you somehow involved the poet in the theme,’ she said. ‘You could do that by making up verb-object or concrete-abstract tides in which “chrysanthemums” was the concrete noun or the object of the verb as the case might be. Then your poem would be both a celebration of chrysanthemums and at the same time a description of some action or situation. Such a treatment of the subject has been tried in the past, but it is a much less hackneyed one. The combining of narrative and lyrical elements in a single treatment makes for freshness and greater freedom.’ 有了,如今以菊花為賓,以人為主,竟擬出幾個題目來,都是兩個字:一個虛字,一個實字,實字便用『菊』字,虛字就用通用門的。如此又是詠菊,又是賦事,前人也沒作過,也不能落套。賦景、詠物兩關著,又新鮮又大方。

‘It sounds a splendid idea,’ said Xiang-yun. ‘But what sort of verbs or abstract nouns had you in mind? Can you give me an example?’ 湘雲笑道:這卻很好。只是不知用何等虛字才好。你先想一個我聽聽。

Bao-chai thought for a bit. 寶釵想了一想,笑道:

‘What about “The Dream of the Chrysanthemums” ?’ 《菊夢》就好。

‘Yes, that’s a good one,’ said Xiang-yun. ‘I’ve thought of one too. Couldn’t we have “The Shadow of the Chrysanthemums”?’ 湘雲笑道:果然好。我也有一個,《菊影》可使得。

‘Ye-e-es,’ said Bao-chai, doubtfully. ‘The trouble is, it’s been used before. Still, if we had a lot of titles we could probably slip it in. I’ve thought of another.’ 寶釵道:也罷了。只是也有人作過,若題目多,這個也算得上。我又有了一個。

‘Well, come on then!’ said Xiang-yun. 湘雲道:快說出來。

‘What about “Questioning the Chrysanthemums”?’ 寶釵道:《問菊》如何。

Xiang-yun slapped the table appreciatively. 湘雲拍案叫妙。

‘That’s a lovely one!’ Presently she added: ‘I’ve thought of another. What do you think of “Seeking the Chrysanthemums”?’ 因接說道:。我也有了,《訪菊》如何。

‘That should be interesting,’ said Bao-chai. ‘Let’s start making a list. We’ll write down up to ten titles and then see what we think of them.’ 寶釵也贊有趣,因說道:越性擬出十個來,寫上再定。

The two of them busied themselves for some minutes grinding ink and softening a brush. Xiang-yun then proceeded to write down the titles at Bao-chai’s dictation. Soon they had ten. Xiang-yun read them over. 說著,二人研墨蘸筆,湘雲便寫,寶釵便念,一時湊了十個。湘雲看了一遍,又笑道:

‘Ten doesn’t make a set,’ she said. ‘We need two more to make a round dozen, then we shall have just the right number for a little album.’ 十個還不成幅,越性湊成十二個便全了,也如人家的字畫冊頁一樣。

Bao-chai supplied two more without too much difficulty. 寶釵聽說,又想了兩個,一共湊成十二。

‘If we’re thinking in terms of a sequence of poems,’ she said, ‘we may as well, while we’re about it, arrange these titles in some sort of order.’ 又說道:既這樣,一發編出它個次序先後來。

‘That’s it!’ said Xiang-yun. ‘Then they will be all ready for making our “Chrysanthemum Album” with afterwards.’ 湘雲道:如此更妙,竟弄成個菊譜了。

“‘Remembering the Chrysanthemums” should come first,’ said Bao-chai. 寶釵道:起首是《憶菊》。

‘Now, let’s see. When you remember them, you realize you haven’t got any, so you go and look for some. So “Seeking the Chrysanthemums” will be the second title. 憶之不得,故訪,第二是《訪菊》。

‘Well, having found some, you will want to plant them; so “Planting the Chrysanthemums” will be the third title. 訪之既得,便種,第三是《種菊》。

‘After you’ve planted them and the flowers have come out, you’ll want to stand and look at them; so the fourth title will be “Admiring the Chrysanthemums”. 種既盛開,故相對而賞,第四是《對菊》。

‘You won’t be able to have enough of them by just standing and admiring them, so you’ll naturally want to pick some and arrange them in a vase so that you can enjoy them indoors. That means “Arranging the Chrysanthemums” for Number Five. 相對而興有餘,故折來供瓶為玩,第五是《供菊》。

‘But however much you enjoy them, you will feel that they somehow lack their full lustre without words to grace them, and so you will want to celebrate them in verse. That means “Celebrating the Chrysanthemums” will be the sixth title. 既供而不吟,亦覺菊無彩色,第六便是《詠菊》。

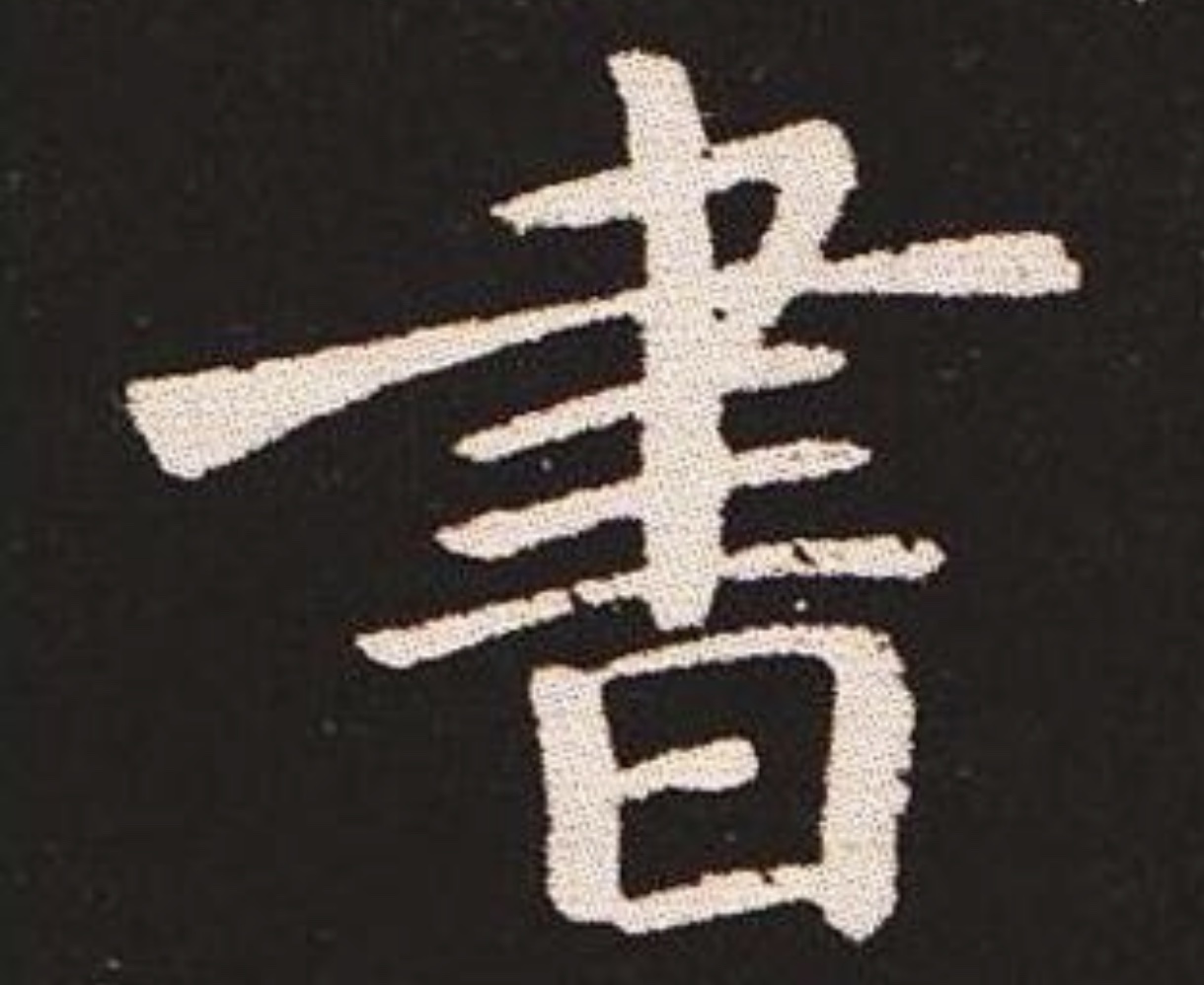

‘Well now, let’s suppose you’ve just finished writing some verses about them. You’ve got the ink ready-made and the brush is still in your hand and you feel like paying the chrysanthemums a further tribute. What should you do but paint them? That’s Number Seven. “Painting the Chrysanthemums”. 既入詞章,不可不供筆墨,第七便是《畫菊》。

‘Now in spite of these silent tributes, you still don’t know the secret of the chrysanthemums’ mysterious charm and you can’t resist asking them. Which brings us to Number Eight “Questioning the Chrysanthemums”. 既為菊如是碌碌,究竟不知菊有何妙處,不禁有所問,第八便是《問菊》。

‘And if the chrysanthemums could really reply, it would be so delightful that you would want to have them near you all the time — and how better than by “Wearing the Chrysanthemums”? That’s Number Nine. 菊如解語,使人狂喜不禁,第九便是《簪菊》。

‘That brings us to the end of the verb-object titles which involve the poet himself as the understood subject of the action. But there remain other kinds of treatment, in which we consider the flowers by themselves without postulating the presence of the poet. So we have “The Shadow of the Chrysanthemums” and “The Dream of the Chrysanthemums” as Numbers Ten and Eleven. 如此人事雖盡,猶有菊之可詠者,《菊影》《菊夢》二首續在第十第十一。

‘And of course “The Death of the Chrysanthemums” at the end of the album to round off on a suitable note of melancholy. 末卷便以《殘菊》總收前題之盛。

‘There you are! All three months of autumn condensed into a single sequence of a dozen poems!’ 這便是三秋的好景妙事都有了。

Xiang-yun recopied the twelve titles in the order that Bao-chai had indicated, then, after running her eye rapidly over them, she asked Bao-chai what rhyme-scheme they should set. 湘雲依言將題錄出,又看了一回,又問:該限何韻。

‘I have always disliked set rhymes,’ said Bao-chai. ‘If you have a good poem in the making, why shackle it with the constraints of an arbitrary rhyme-scheme? Let us leave set rhymes to vulgar pedants; all we need do is give out the titles and let the others choose their own rhyme-schemes for themselves. After all, the object of the exercise is to give people enjoyment — the enjoyment gained by producing an occasional felicitous line. We aren’t out to make things difficult for them.’ 寶釵道:我平生最不喜限韻的,分明有好詩,何苦為韻所縛。咱們別學那小家派,只出題,不拘韻。原為大家偶得了好句取樂,並不為此而難人。

‘I entirely agree,’ said Xiang-yun. ‘And I am sure that in this way we shall get better poems. There’s just one thing, though: we have twelve titles now but only five people writing poems. Presumably we aren’t going to ask each of them to produce a poem for every one of the titles?’ 湘雲道:這話很是。這樣大家的詩還進一層。但只是咱們五個人,這十二個題目,難道每人作十二首不成。

‘Oh no, that would be much too difficult,’ said Bao-chai. ‘Make a fair copy of the list of titles, merely indicating that the poems are to be octets in Regulated Verse, put it up on the wall where everyone can see it, and then simply let them choose whichever titles they like. If anyone has the energy to do them all, they are welcome to try. If they can’t manage more than one, let them do just one. Skill and speed are what we shall be looking for. As soon as all of the twelve titles have been covered, we shall call a halt, and anyone who goes on writing after that will be made to pay a penalty.’ 寶釵道:那也太難人了。將這題目謄好,都要七言律詩,明日貼在牆上。他們看了,誰作那一個就作那一個。有力量者,十二首都作也可;不能的,一首不成也可。高才捷足者為尊。若十二首已全,便不許他後趕著又作,罰他就完了。

Xiang-yun did not see that this last stipulation was necessary, but otherwise agreed with her, and the two girls, having satisfied themselves that their plans for the morrow were now complete, put out the light and composed themselves for sleep. 湘雲道:這倒也罷了。二人商議妥貼,方才息燈安寢。

As to the outcome of their plans: that will be told in the following chapter. 要知端的,且聽下回分解。

***

From Chapter 38

River Queen triumphs in her treatment of chrysanthemum themes

林瀟湘魁奪菊花詩

Then [Xiang-yun] took the list of poem-titles and pinned it to the inside wall of the pavilion. 湘雲便取了詩題,用針綰在牆上。

‘Very original!’ the others commented when they had finished reading the titles, but went on to express the fear that they might find them difficult to write on. 眾人看了都說:新奇固新奇,只怕作不出來。

Xiang-yun explained what they had decided about rhymes: viz. that there should be no set rhyme-scheme and everyone should be free to choose their own. 湘雲又把不限韻的原故說了一番。

‘Now that’s what I call sensible!’ said Bao-yu. ‘I can’t stand set rhymes.’ 寶玉道:這才是正理,我也最不喜限韻。

Dai-yu had a barrel-shaped porcelain tabouret moved up to the verandah’s edge, and having selected a fishing-rod for herself, sat leaning on the railing, fishing. Bao-chai sat for some time silently contemplating a spray of cassia she had picked, then, leaning over the railings and idly plucking off the flowerets, dropped them one by one into the water and watched the fish swim up from below and nibble at them with plopping noises as they floated on the surface. Xiang-yun for the most part sat quietly musing, occasionally getting up to look after Aroma and the other maids at the table outside, or to make sure that the people sitting on the carpets were getting enough to eat and drink. Tan-chun stood with Li Wan and Xi-chun in the shade of a weeping willow, watching the water-fowl. Ying-chun sat apart from the rest beneath a flowering tree, stringing jasmine blossoms into a flower-chain with a needle and thread. 林黛玉因不大吃酒,又不吃螃蟹,自命人掇了一個繡墩倚欄杆坐著,拿著釣竿釣魚。寶釵手裏拿著一枝桂花玩了一回,俯在窗檻上掐了桂蕊擲向水面,引得游魚浮上來唼喋。湘雲出一回神,又讓一回襲人等,又招呼山坡下的眾人只管放量吃。探春和李紈、惜春立在垂柳陰中看鷗鷺。迎春又獨在花陰下拿著花針穿茉莉花。

Bao-yu watched Dai-yu fishing for a bit, then went over and leaned on the railings and talked with Bao-chai for a bit, and finally, after watching Aroma and the other maids eating and drinking at their table, ended up by drinking with them himself while Aroma shelled a crab for him. 寶玉又看了一回黛玉釣魚,一回又擠在寶釵旁邊說笑兩句,一回又看襲人等吃螃蟹,自己也陪她飲兩口酒。襲人又剝一殼肉給他吃。

Presently Dai-yu put down her fishing-rod, went over to the central table, took up a silver ‘self-service’ wine-kettle whose surface was carved with a nielloed plum-flower pattern, and, having selected a little shallow, rose-quartz winecup, was just about to pour herself a drink, when a maid observed her and came hurrying up to do it for her. 黛玉放下釣竿,走至座間,拿起那烏銀梅花自斟壺來,揀了一個小小的海棠凍石蕉葉杯。丫鬟看見,知她要飲酒,忙著走上來斟。

‘No, let me pour it myself,’ said Dai-yu. ‘That is half the fun. You get on with your party.’ 黛玉道:你們只管吃去,讓我自己斟才有趣兒。

So saying, she proceeded to half-fill the tiny receptacle with liquor from the silver kettle. But it proved to be yellow rice-wine, whereas what she wanted was spirits. 說著便斟了半盞,看時,卻是黃酒,因說道:

‘I only ate a small amount of crab,’ she said, ‘but it has given me a slight heart-burn. What I really need is some very hot samshoo.’ 我吃了一點子螃蟹,覺得心口微微的疼,須得熱熱的吃口燒酒。

‘We have some,’ said Bao-yu, and quickly ordered a kettle of special mimosa-flavoured samshoo to be heated for her. 寶玉忙道:有燒酒。便命將那合歡花浸的酒燙一壺來。

Dai-yu took only a sip of it before putting the wine cup down again. 黛玉也只吃了一口,便放下了。

Presently Bao-chai strolled up and helped herself to the samshoo. She, too, put her cup down after taking only a tiny mouthful of it. Then she moistened a brush with ink, and going over to the list of titles, put a tick over the first one, ‘Remembering the Chrysanthemums’, and wrote the word ‘Allspice’ underneath it. 寶釵也走過來,另拿了一只杯來,也飲了一口放下,便蘸筆至牆上把頭一個《憶菊》勾了,底下又贅了一個「蘅」字。

‘Please leave Number Two for me, Chai,’ said Bao-yu anxiously. ‘I’ve already thought of four lines for it.’ 寶玉忙道:好姐姐,第二個我已經有了四句了,你讓我作罷。

Bao-chai laughed. 寶釵笑道:

‘I’ve had a hard enough job thinking of lines for this first one. You’ve nothing to worry about as far as I’m concerned.’ 我好容易有了一首,你就忙得這樣。

Dai-yu, without saying a word, quietly relieved Bao-chai of the brush, ticked first ‘Questioning the Chrysanthemums’ and then the eleventh title, ‘The Dream of the Chrysanthemums’, and wrote ‘River’ underneath each of them. 黛玉也不說話,接過筆來把第八個《問菊》勾了,接著把第十一個《菊夢》也勾了,也贅上一個瀟字。

After her, Bao-yu took up the brush and ticked ‘Seeking the Chrysanthemums’. He signed himself ‘Green’. 寶玉也拿起筆來,將第二個《訪菊》也勾了,也贅上一個怡字。

Tan-chun now drifted over and looked at the list. 探春走來看看道:

‘Oh, hasn’t anyone chosen “Wearing the Chrysanthemums” yet?’ she said. ‘Let me do that one.’

She turned, smilingly, to Bao-yu and pointed a warning finger at him. 竟沒人作《簪菊》,讓我作這《簪菊》。又指著寶玉笑道:

‘We’ve just made a new rule, by the way. No naked ladies this time, please. You have been warned!’ 才宣過總不許帶出閨閣字樣來,你可要留神!

Xiang-yun strolled up while she was saying this and ticked Numbers Four and Five — ‘Admiring the Chrysanthemums’ and ‘Arranging the Chrysanthemums’ — in rapid succession. She signed herself ‘Xiang’ underneath them. 說著,只見湘雲走來,將第四、第五《對菊》《供菊》一連兩個都勾了,也贅上一個「湘」字。

‘You ought to have a pen-name like the rest of us,’ said Tan-chun. 探春道:你也該起個號。

‘There are various pavilions and studios at home, of course,’ said Xiang-yun, ‘but I don’t live in any of them. It would be rather pointless to call myself after a building like the rest of you.’ 湘雲笑道︰我們家裏如今雖有幾處軒館,我又不住著,借了來也沒趣。

‘What about that water pavilion “Above the Clouds” that Lady Jia was telling us about?’ said Bao-chai. ‘You could call that yours. Even if it doesn’t exist any more, you can pretend that it would have been yours. You should call yourself “Cloud Maiden”.’ 寶釵笑道:方才老太太說,你們家也有這麼個水亭叫『枕霞閣』,難道不是你的。如今雖沒了,你到底是舊主人。

‘Yes, yes,’ said the others; and before Xiang-yun herself could do anything, Bao-yu had crossed out the ‘Xiang’ and substituted the word ‘Cloud’ beneath it. 眾人都道有理,寶玉不待湘雲動手,便代將湘字抹了,改了一個霞字。

In less time than it would take to eat a meal, poems had been completed for each of the twelve titles. The young poets then wrote out their poems and handed them in to Ying-chun, who copied them out, each with the full pen-name of its author, on to the finest Snow Wave notepaper. 又有頓飯工夫,十二題已全,各自謄出來,都交與迎春,另拿了一張雪浪箋過來,一並謄錄出來,某人作的底下贅明某人的號。

Li Wan then read them all through, the others overlooking her. 李紈等從頭看起:

Remembering the Chrysanthemums 憶菊

Lady Allspice 蘅蕪君

The autumn wind that through the knotgrass blows

Blurs the sad gazer’s eye with unshed tears;

But autumn’s guest, who last year graced this plot,

Only, as yet, in dreams of night appears.

The wild geese from the North are now returning;

The dhobi’s thump at evening fills my ears.

Those golden flowers for which you see me pine

I’ll meet once more at this year’s Double Nine.

悵望西風抱悶思,

蓼紅葦白斷腸時。

空籬舊圃秋無跡,

瘦月清霜夢有知。

念念心隨歸雁遠,

寥寥坐聽晚砧痴。

誰憐為我黃花病。

慰語重陽會有期。

Seeking the Chrysanthemum 訪菊

Green Boy 怡紅公子

The crisp day bids us go on an excursion —

Resistant to the wineshop door’s temptation —

Some garden, where, before the frosts, was planted

The glory of autumn, being our destination:

Which after weary walk having found, we’ll sing

An autumn song with unsubdued elation.

And you, gold flowers, if all the poet told

You understood, would not refuse his gold!

閑趁霜晴試一遊,

酒杯藥盞莫淹留。

霜前月下誰家種。

檻外籬邊何處愁。

蠟屐遠來情得得,

冷吟不盡興悠悠。

黃花若解憐詩客,

休負今朝掛杖頭。

Planting the Chrysanthemums 種菊

Green Boy 怡紅公子

Brought from their nursery and, with loving hands,

Planted along the fence and by the door—

A shower last night their wilting leaves revived,

Opening the morning-buds all silver-hoar.

Sweet flowers! a thousand autumn songs I’ll sing

To praise your beauty, and libations pour,

And water you, and ridge with earth around.

No dust on my wet well-path shall be found!

攜鋤秋圃自移來,

籬畔庭前故故栽。

昨夜不期經雨活,

今朝猶喜帶霜開。

冷吟秋色詩千首,

醉酹寒香酒一杯。

泉溉泥封勤護惜,

好知井徑絕塵埃。

Admiring the Chrysanthemums 對菊

Cloud Maiden 枕霞舊友

Transplanted treasures, dear to me as gold —

Both the pale clumps and those of darker hue!

Rare-headed by your wintry bed I sit

And, musing, hug my knees and sing to you.

None more than you the villain world disdains;

None understands your proud heart as I do.

The precious hours of autumn I’ll not waste,

But bide with you and savour their full taste.

別圃移來貴比金,

一叢淺淡一叢深。

蕭疏籬畔科頭坐,

清冷香中抱膝吟。

數去更無君傲世,

看來惟有我知音。

秋光荏苒休辜負,

相對原宜惜寸陰。

Arranging the Chrysanthemums 供菊

Cloud Maiden 枕霞舊友

What greater pleasure than the lute to strum

Or sip wine by your delicate display?

To hold the garden’s fragrance in one vase,

And see all autumn in a single spray?

On frosty nights I’ll dream you back again,

Brave in your garden bed at close of day.

Since with your shy disdain I sympathize,

’Tis you, not summer’s gaudy blooms I prize.

彈琴酌酒喜堪儔,

几案婷婷點綴幽。

隔座香分三徑露,

拋書人對一枝秋。

霜清紙帳來新夢,

圃冷斜陽憶舊遊。

傲世也因同氣味,

春風桃李未淹留。

Celebrating the Chrysanthemums 詠菊

River Queen 瀟湘妃子

Down garden walks, in search of inspiration,

A restless demon drives me all the time;

Then brush blooms into praises, and the mouth

Grows acrid-sweet, hymning those scents sublime.

Yet easier ’twere a world of grief to tell

Than to lock autumn’s secret in one rhyme.

That miracle old Tao did once attain;

Since when a thousand bards have tried in vain.

無賴詩魔昏曉侵,

繞籬欹石自沉音。

毫端蘊秀臨霜寫,

口齒噙香對月吟。

滿紙自憐題素怨,

片言誰解訴秋心。

一從陶令平章後,

千古高風說到今。

Painting the Chrysanthemums 畫菊

Lady Allspice 蘅蕪君

The brush that praised them, eager for more tasks,

Would paint them now for painting’s no great cost

When cunning black-ink blots the flowers’ leaves make,

And white the petals, silvered o’er with frost.

Fresh scents of autumn from the paper rise,

And shapes unmoving by the wind are tossed.

No need at Double Ninth live flowers to pluck:

These living seem, upon a fine screen stuck!

詩餘戲筆不知狂,

豈是丹青費較量。

聚葉潑成千點墨,

攢花染出幾痕霜。

淡濃神會風前影,

跳脫秋生腕底香。

莫認東籬閑採掇,

粘屏聊以慰重陽。

Questioning the Chrysanthemums 問菊

River Queen 瀟湘妃子

Since none else autumn’s mystery can explain,

I come with murmured questions to your gate:

Who, world-disdainer, shares your hiding-place?

Of all the flowers why do yours bloom so late?

The garden silent lies in frosty dew;

The geese return; the cricket mourns his fate.

Let not speech from your silent world be banned:

Converse with me, since me you understand!

欲訊秋情眾莫知,

喃喃負手叩東籬。

孤標傲世偕誰隱。

一樣花開為底遲。

圃露庭霜何寂寞,

鴻歸蛩病可相思。

休言舉世無談者,

解語何妨片語時。

Wearing the Chrysanthemums 簪菊

Plantain Lover 蕉下客

Just to admire and not for our adornment

Were these reared and arranged with so much care;

Yet young Sir Fop, with whom flowers are a passion,

And drunk old Tao both dote on flowers to wear.

One’s head-cloth reeks of autumn’s acrid perfume;

Chill dew of autumn pearls the other’s hair

The vulgar crowd, which nothing understands,

Stops in the street and, jeering, claps its hands.

瓶供籬栽日日忙,

折來休認鏡中妝。

長安公子因花癖,

彭澤先生是酒狂。

短髪冷沾三徑露,

葛巾香染九秋霜。

高情不入時人眼,

拍手憑他笑路旁。

The Shadow of the Chrysanthemums 菊影

Cloud Maiden 枕霞舊友

The autumn moonlight through the garden steals,

Filtered in patches variously bright.

Flowers by the house as silhouettes appear;

Flowers by the fence are flecked with coins of light.

In the flowers’ wintry scent their souls reside,

Not in those frost-forms, than a dream more slight.

Even the gross vandal, squinting through drunken eyes,

Can, by their scents, the crushed flowers recognize.

秋光疊疊復重重,

潛度偷移三徑中。

窗隔疏燈描遠近,

籬篩破月鎖玲瓏。

寒芳留照魂應駐,

霜印傳神夢也空。

珍重暗香休踏碎,

憑誰醉眼認朦朧。

The Dream of the Chrysanthemums 菊夢

River Queen 瀟湘妃子

Light-headed in my autumn bed I lie

And seem to chase the moon across the sky.

Well, if immortal, I’ll go seek old Tao,

Not imitate Zhuang’s flittering butterfly!

Following the wild goose, into sleep I slid;

From which now, startled by the cricket’s cry,

Midst cold and fog and dying leaves I wake,

With no one by to tell of my heart’s ache.

籬畔秋酣一覺清,

和雲伴月不分明。

登仙非慕莊生蝶,

憶舊還尋陶令盟。

睡去依依隨雁斷,

驚回故故惱蛩鳴。

醒時幽怨同誰訴。

衰草寒煙無限情。

The Death of the Chrysanthemums 殘菊

Plantain Lover 蕉下客

The feasting over and the first snow fallen,

The flowers frost-stricken lie or sideways lean,

Their perfume lingering, but their gold hue dimmed

And few poor, tattered leaves bereft of green.

Now under moonlit bench the cricket shrills,

And weary goose-files in the cold sky are seen.

Yet of your passing let me not complain:

Next autumn equinox we’ll meet again!

露凝霜重漸傾欹,

宴賞才過小雪時。

蒂有餘香金淡泊,

枝無全葉翠離披。

半床落月蛩聲病,

萬裏寒雲雁陣遲。

明歲秋風知再會,

暫時分手莫相思。

Each poem was praised in turn, and the reading of the whole twelve concluded amidst cries of mutual admiration. 眾人看一首贊一首,彼此稱揚不絕。

‘Now just a moment!’ said Li Wan, interrupting their encomiums. ‘Let me first try to give you an impartial judgement. I think there were good lines in all of the poems, but comparing one with another, it seems to be that one is bound to place “Celebrating the Chrysanthemums” first, with “Questioning the Chrysanthemums” second and “The Dream of the Chrysanthemums” third. The titles themselves were original, and particularly in their treatment of the subject these are three highly original poems. So I think that today the first place must undoubtedly go to River Queen. After those first three I would place “Wearing the Chrysanthemums”, “Admiring the Chrysanthemums”, “Arranging the Chrysanthemums”, “Painting the Chrysanthemums” and “Remembering the Chrysanthemums” in that order.’ 李紈笑道:等我從公評來。通篇看來,各人各人的警句。今日公評:《詠菊》第一,《問菊》第二,《菊夢》第三,題目新,詩也新,立意更新,惱不得要推瀟湘妃子為魁了;然後《簪菊》《對菊》《供菊》《畫菊》《憶菊》次之。

Bao-yu clapped his hands delightedly. 寶玉聽說,喜得拍手叫:

‘Absolutely right! A very fair judgement!’ 極是,極公道。

‘I’m afraid mine aren’t really all that good,’ said Dai-yu. ‘They are a bit too contrived.’ 黛玉道:我那首也不好,到底傷於纖巧些。

‘There’s nothing wrong with a bit of contrivance,’ said Li Wan. ‘One doesn’t want the structure of a poem to stand out too ruggedly.’ 李紈道:巧得卻好,不露堆砌生硬。

‘I very much like that couplet of Cloud Maiden’s,’ said Dai-yu: 黛玉道:據我看來,頭一句好的是

‘On frosty nights I’ll dream you back again,

Brave in your garden bed at close of day.

圃冷斜陽憶舊遊。

‘It’s a technique that painters call “white-backing”. That marvellous couplet that comes before it:

To hold the garden’s fragrance in a vase,

And see all autumn in a single spray

‘already sums up all there is to be said on the subject of flower arrangement. You feel that she’s left herself nothing else to say. So what does she do? She goes back to the time before the flowers were arranged—before they were picked, even. That going back in her “frosty nights’ couplet is a very subtle way of throwing the main theme into relief, just as the artist’s white-backing sharpens the highlights on the other side of the painting.’ 這句背面傅粉。拋書人對一枝秋已經妙絕,將供菊說完,沒處再說,故翻回來想到未折未供之先,意思深透。

Li Wan smiled. 李紈笑道:

‘That may be so; but your own “acrid-sweet” couplet is more than a match for it.’ 固如此說,你的口齒噙香一句也敵得過了。

‘I think Lady Allspice dealt with her subject most effectively,’ said Tan-chun. ‘That couplet of hers:

But autumn’s guest, who last year graced this plot,

Only as yet in dreams of night appears

‘seems to bring out the idea of remembering so vividly.’ 探春又道:到底要算蘅蕪君沉著,秋無跡,夢有知,把個憶字竟烘染出來了。

‘Well, your “head-cloth reeking of autumn’s acrid perfume” and “chill dew of autumn pearling the hair” give a pretty vivid image of wearing chrysanthemums,’ said Bao-chai with a laugh. 寶釵笑道:你的短鬢冷沾,葛巾香染,也就把簪菊形容得一個縫兒也沒了。

‘And River Queen’s “who shares your hiding place?” “why do you bloom so late?”,’ said Xiang-yun, smiling mischievously, ‘make so thorough a job of questioning them, that one feels the poor things must have been quite tongue-tied!’ 湘雲笑道:偕誰隱,為底遲,真真把個菊花問的無言可對。

‘For that matter,’ said Li Wan, entering into the spirit of the thing, ‘your persistent haunting of the chrysanthemums — “sitting bare-headed by their wintry bed” and “hugging your knees and singing to them”—makes one suspect that if the chrysanthemums really had consciousness, they might, in the end, have grown just a tiny bit tired of your company!’ 李紈笑道:你的科頭坐,抱膝吟,竟一時也捨不得別開,菊花有知,也必膩煩了。

The others all laughed. 說得大家都笑了。

‘I seem to be bottom again,’ said Bao-yu ruefully. ‘Though I must say I should have thought that

… to go on an excursion—

Some garden where… was planted

The glory of autumn being our destination

‘and so forth was a perfectly satisfactory exposition of “seeking the chrysanthemums”; and that

A shower last night the wilting leaves revived,

Opening the morning-buds all silver-hoar

‘dealt with the theme of transplanting chrysanthemums rather successfully. Heigh-ho! I suppose it’s just that I couldn’t produce anything quite as good as River Queen’s “acrid-sweet” line, or Cloud Maiden’s “bare-headed by your wintry bed”, or Plaintain lover’s “reeking head-cloth” or “few poor, tattered leaves”, or Lady Allspice’s “autumn guest in dreams of night appears”. 寶玉笑道:我又落第。難道誰家種,何處秋,蠟屐遠來,冷吟不盡,都不是訪,昨夜雨,今朝霜,都不是種不成。但恨敵不上口齒噙香對月吟、清冷香中抱膝吟、鬢、葛巾、金淡泊、翠離披、秋無跡、夢有知這幾句罷了。

‘Well, never mind,’ he went on, after a moment’s reflection. ‘Perhaps tomorrow or the day after, if I’ve got the time, I’ll try to do all twelve of them again on my own.’ 又道:明兒閑了,我一個人作出十二首來。

‘Your poems were perfectly all right,’ said Li Wan consolingly. ‘It’s simply as you yourself have just said that they didn’t have anything quite as good as the lines you have mentioned.’ 李紈道:你的也好,只是不及這幾句新巧就是了。

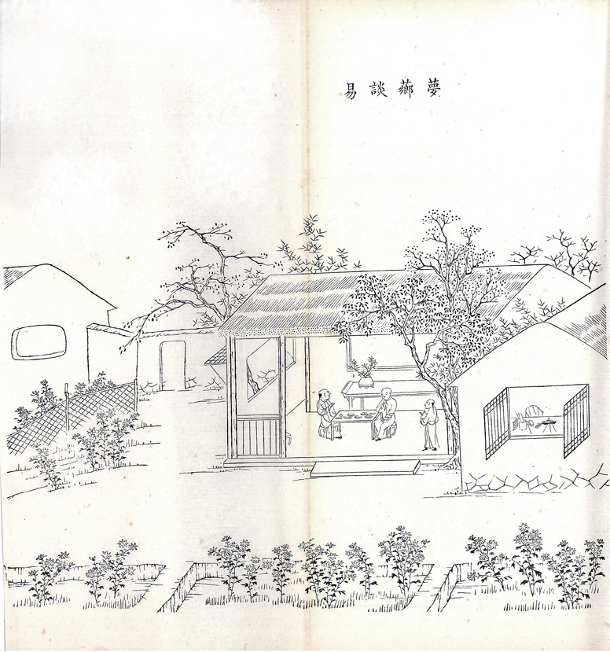

A Bannerman’s Double Ninth

Two Episodes from Lincing’s Tracks in the Snow

This first episode is from Mengxiang Discoursing on the I Ching 夢薌談易, Episode 44 in Tracks in the Snow 鴻雪姻緣圖記, Wanggiyan Lincing 完顏麟慶, translated and annotated by Yang Tsung-han 楊宗翰, edited by John Minford with Rachel May. The indented annotations are by Lincing, Yang Tsung-han and John Minford respectively. The full text was published in China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 21 (March 2010). This, and the second episode below, also translated by Yang and edited by Christina Sanderson, are part of the Tracks in the Snow project of the Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology.

— The Editor

Mengxiang’s Chrysanthemums

In the Imperial Capital, it is universally agreed that Wo Futang, the Supervisory Censor,

Lincing: A Manchu, named Kejinga 克精額.

and Zhao Xiang’an

Lincing: Prospective heir of a hereditary military title. His name was Shi 鉽, and a native of Zhili 直隸. Yang Tsung-han: Another example of the absurd and exasperating pseudo-literary style whereby an ancient or obsolete official title is used to indicate a modern official post, or just as a flattering term with no actual post. The title sheren 舍人 began with the Qin 秦 dynasty but continued in various forms indicating various duties until the Qing 清 dynasty, when it was definitely abolished altogether! In the Song 宋 and Yuan 元 dynasties it was used as a courteous appellation for the scions of exalted families; in the Ming 明 dynasty it was used to designate the prospective heirs to a hereditary military title.

are the true experts among those who devote themselves to the cultivation of chrysanthemums. It was through the good offices of my friend the Master of Leisure

LC: A Manchu bondservant named Huilin 惠林. YTH: filius terrae. John Minford: Yang adds the Latin, to emphasize that he was a person of lowly origin.

that I had the privilege of calling on both of them to study and admire their flowers.

One day, in the Office of Imperial Historiography, I was talking about the various species of chrysanthemum, when Wen Mengxiang 文夢薌

LC: A Manchu whose personal name was Tong 通, member of the Imperial Bodyguard, participated in the work of compiling the Manchu version of the Veritable Record 實錄 by special recommendation, and was appointed as one of the official compilers; later serving as Lieutenant-General 總兵 [of the Chinese or Green Banner Army 綠營].

said that in his family garden there were some unusual varieties and invited me to go and see them for myself. I did so, and I found it a most delightful experience. He had sumptuous food and drink prepared and invited me to stay, expatiating all the while on the symbols 象 and numbers 數 of the I Ching.

YTH: To divine卜 by scorching the shell of a tortoise is to get the images 象; to divine 筮 by the stalk of a particular plant is to get the numbers 數: Cf. 物生而後有象…而後有…數 (左傳僖公十五年) — in other words, the essential doctrine and function of I Ching — 龜以象示,筮以數告 … 所以知吉凶。

***

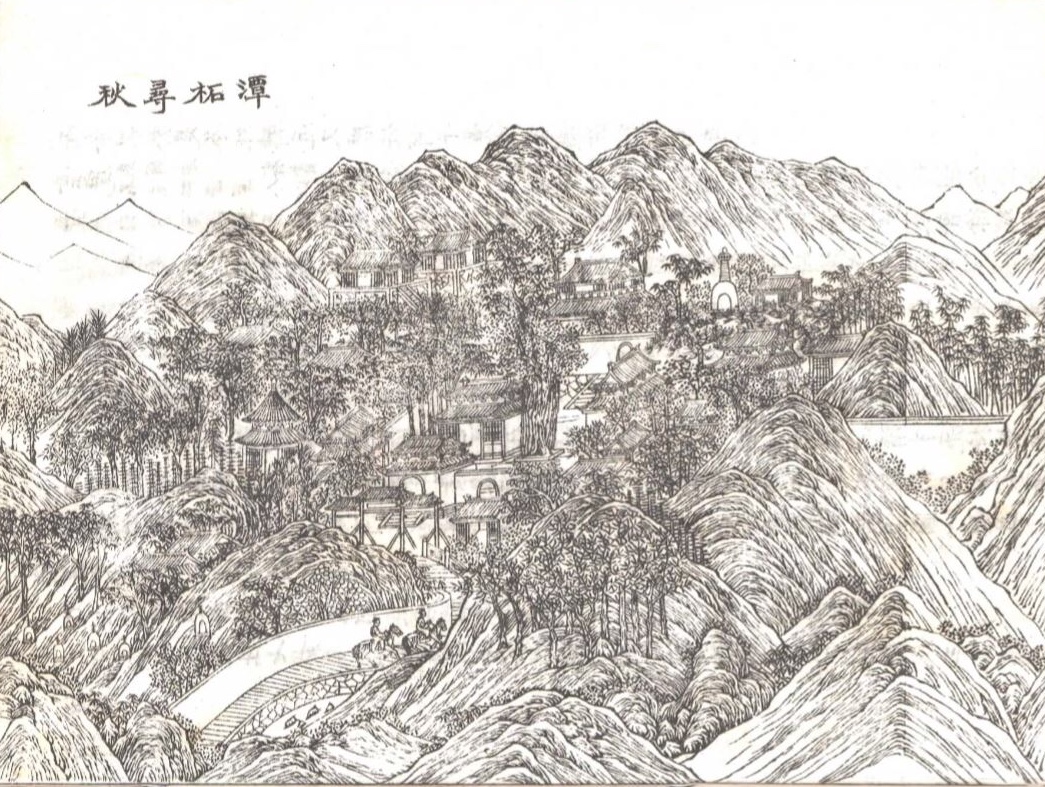

Autumn at the Temple of the Limpid Pool and Wild Mulberry

This second selection is from ‘Autumnal Outing at Tanzhe Temple’ 潭柘尋秋, Episode 43 of Lincing’s Tracks in the Snow, translated by Yang Tsung-han and edited by Christina Sanderson.

At the time the trees on the hill diffused fragrance and the autumnal forest appeared richly and fascinatingly coloured. Meanwhile the splendid buildings interspersed with the plain dull stone pagodas created a scene that combined extravagant beauty with bare simplicity: a fairyland in world of red dust 紅塵仙境. We all sat down in front of the temple gate and told each other stories about climbing up to a high place on the Double Ninth Festival. We came up with over forty anecdotes that day, which was coincidentally the Ninth Day of the Ninth Month.

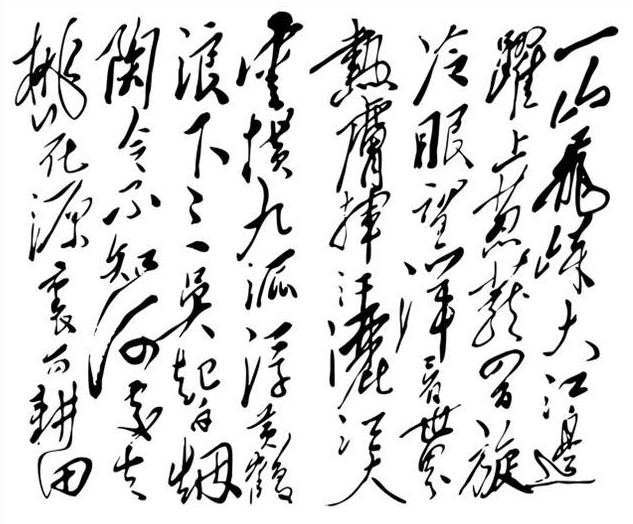

Two Poems by Mao Zedong

The Double Ninth 重陽

— to the tune of Cai sang zi 採桑子

October 1929

Man ages all too easily, not Nature:

Year by year the Double Ninth returns.

On this Double Ninth,

The yellow blooms on the battlefield smell sweeter.

Each year the autumn wind blows fierce,

Unlike spring’s splendour,

Yet surpassing spring’s splendour,

See the endless expanse of frosty sky and water.

人生易老天難老,

歲歲重陽,

今又重陽,

戰地黃花分外香。

一年一度秋風勁,

不似春光,

勝似春光,

寥廓江天萬里霜。

菊香书屋;康熙题联“庭松不改青葱色,盆菊仍靠清净香”的菊香书屋。

Throughout much of the twentieth century Tao Yuanming, his poetry and image, were attacked by left-leaning writers, educators and revolutionaries. Although he was fascinated by the Wei-Jin period and its unfettered writers, Lu Xun allowed his always-prickly superiority to chide Tao’s modern admirers as being ignorant of the productive realities behind the ethereal recluse’s lifestyle. After all, it was argued, the poet would have had servants and laborers working hard to support his lifestyle of leisure and self-indulgent otherworldliness.

Later critics would argue that the ‘field-and-garden poetry’ 田園詩 of the era was actually the product of an intimate involvement of writers like Tao Yuanming in tilling the soil. Regardless, the ancient recluse was excoriated for being a dangerous exemplar for young people in modern China who might be encouraged by his charismatic personality and artistic achievement to eschew politics and nation building in favour of self-cultivation and artistic creativity. Among their number was Cao Juren 曹聚仁, an often-brutal literary figure who, after 1949, was an agent of influence based in Hong Kong.

Cao was particularly dismissive of Feng Zikai, a popular artist and writer who, as we noted earlier, actively cultivated a lifestyle modelled on that of Tao Yuanming during his ‘retirement from the world’ in the 1930s. Feng also wrote in praise of Tao Yuanming’s famous ‘Record of the Peach Blossom Spring’ 桃花源记 as, he said, reading it gave one a ‘temporary escape from the dusty world’ 暫時脫離塵世.

The tensions between withdrawal from or engagement in the realm of the party-state 黨天下 persist in the twenty-first century.

Ascent of Lu Shan

登廬山

The most grotesque abuse of Tao, however, was authored by none other than the Communist Party leader Mao Zedong. As the Great Leap Forward swept the nation in the late 1950s, Mao convened a meeting at the former KMT summer retreat on Lu Shan in Jiangxi province, the same mountain that Tao Yuanming had ‘suddenly seen’ some 1400 years earlier.

On 1 July 1959, Mao, ‘dizzy with success’ as he contemplated China’s premature leap into communism, wrote a poem of self-congratulation at Lu Shan in which he dismissed Tao Yuanming’s dated view of utopia as expressed in his parable, ‘The Peach Blossom Spring’ 桃花源記. For, Mao-as-poet claimed, it was the Communists who had finally realized the dreams of the ancient writer. And this just as the policies championed by Mao were already leading to widespread rural poverty and starvation. By the early 1960s the Great Leap into the future had created the largest man-made famine in human history.

Perching as after flight, the mountain towers over the Yangtze;

I have overleapt four hundred twists to its green crest.

Cold-eyed I survey the world beyond the seas;

A hot wind spatters raindrops on the sky-brooded waters.

Clouds cluster over the nine streams, the yellow crane floating,

And billows roll on to the eastern coast, white foam flying.

Who knows whither Prefect Tao Yuanming is gone

Now that he can till fields in the Land of Peach Blossoms?

一山飛峙大江邊,

躍上蔥蘢四百旋。

冷眼向洋看世界,

熱風吹雨灑江天。

雲橫九派浮黃鶴,

浪下三吳起白煙。

陶令不知何處去,

桃花源里可耕田?

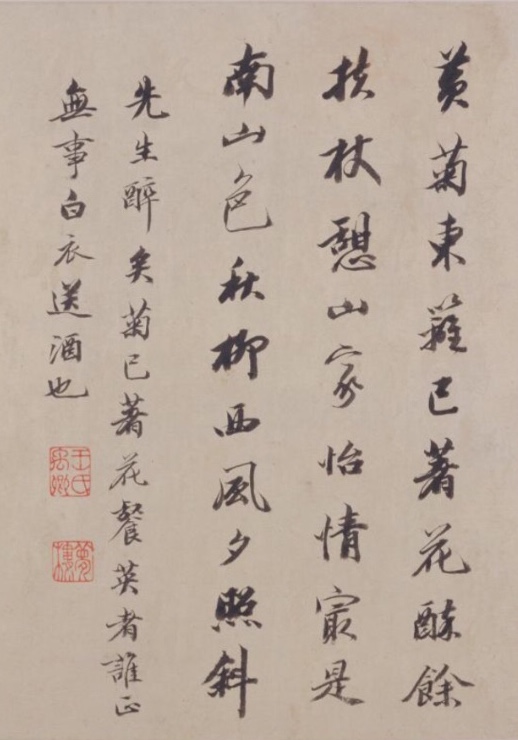

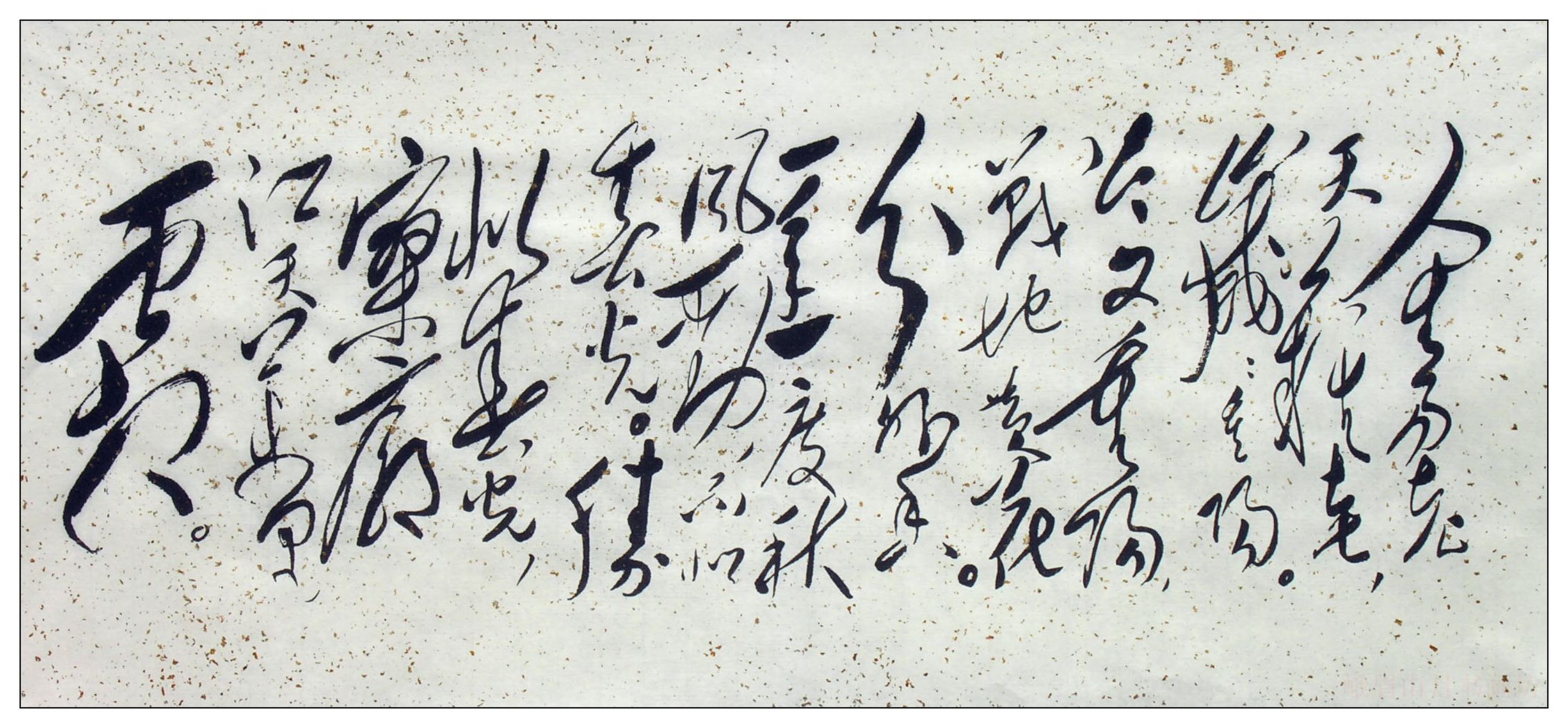

An Impromptu Verse by Li Shutong

A poem by Li Shutong 李叔同 (1880-1942, later Dharma Master Hongyi 弘一法師) in the hand of his student Feng Zikai 豐子愷, written at the behest of [Peng] Changqing 彭長卿, a noted collector of letters and calligraphic inscriptions. —Ed.

***

An impromptu poem composed after visiting the Small Orchid Pavilion and written on a wall. The scene was unchanged but my mood was dark, this on the First Day of the Ninth Month (1904). 重游小兰亭,风景依稀,心绪殊恶,口占二十八字题壁,时九月望一日也。

Night and the west wind turns cold

Blowing the yellow flowers around the balustrade

So fleeting the spring and autumnal change

Before morning watch I rouse from my dreams.

一夜西風驀地寒,

吹將黃葉上欄乾。

春來秋去忙如許,

未到晨鐘夢已闌。

***

Not long after composing this poem in 1904 Li Shutong went to live in Japan where, among other things, he helped found a theatrical troupe called the Spring Willow Society 春柳社. After returning to China he taught in Hangzhou. He later took the tonsure and became a monk. As a prominent advocate of a form of disciplinary Buddhism he is remembered as a stern but otherworldly figure.

The Late-Chrysanthemum Flower

The Chrysanthemums in the Eastern Garden

Bo Juyi

The days of my youth left me long ago;

And now in their turn dwindle my years of prime.

With what thoughts of sadness and loneliness

I walk again in this cold, deserted place!

In the midst of the garden long I stand alone;

The sunshine, faint; the wind and dew chill.

The autumn lettuce is tangled and turned to seed;

The fair trees are blighted and withered away.

All that is left are a few chrysanthemum-flowers

That have newly opened beneath the wattled fence.

I had brought wine and meant to fill my cup,

When the sight of these made me stay my hand.

I remember, when I was young,

How easily my mood changed from sad to gay.

If I saw wine, no matter at what season,

Before I drank it, my heart was already glad.

But now that age comes,

A moment of joy is harder and harder to get.

And always I fear that when I am quite old

The strongest liquor will leave me comfortless.

Therefore I ask you, late chrysanthemum-flower

At this sad season why do you bloom alone?

Though well I know that it was not for my sake,

Taught by you, for a while I will open my face.

東園玩菊

白居易

少年昨已去,

芳歲今又闌。

如何寂寞意,

復此荒涼園。

園中獨立久,

日澹風露寒。

秋蔬盡蕪沒,

好樹亦凋殘。

唯有數叢菊,

新開籬落間。

攜觴聊就酌,

為爾一留連。

憶我少小日,

易為興所牽。

見酒無時節,

未飲已欣然。

近從年長來,

漸覺取樂難。

常恐更衰老,

強飲亦無歡。

顧謂爾菊花,

後時何獨鮮。

誠知不為我,

借爾暫開顏。

— translated by Arthur Waley

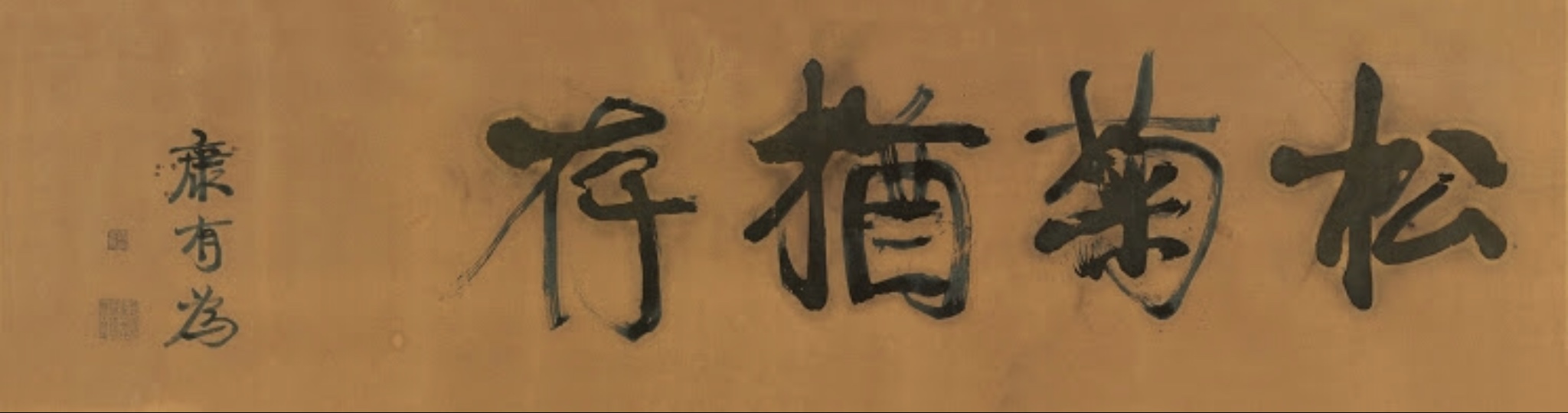

Pines and Chrysanthemums Remain

‘The three paths are almost obliterated/ But pines and chrysanthemums are still here’ 三徑就荒,松菊猶存 is from Tao Yuanming’s ‘The Return: A Rhapsody’ 歸去來辭, a work inspired by the poet’s retirement from office in 405 CE.