Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

戴晴與1989

The focus of this two-part commemoration of the June Fourth Beijing Massacre of 1989 is Dai Qing, reporter, novelist and China’s first post-Mao historical investigative journalist.

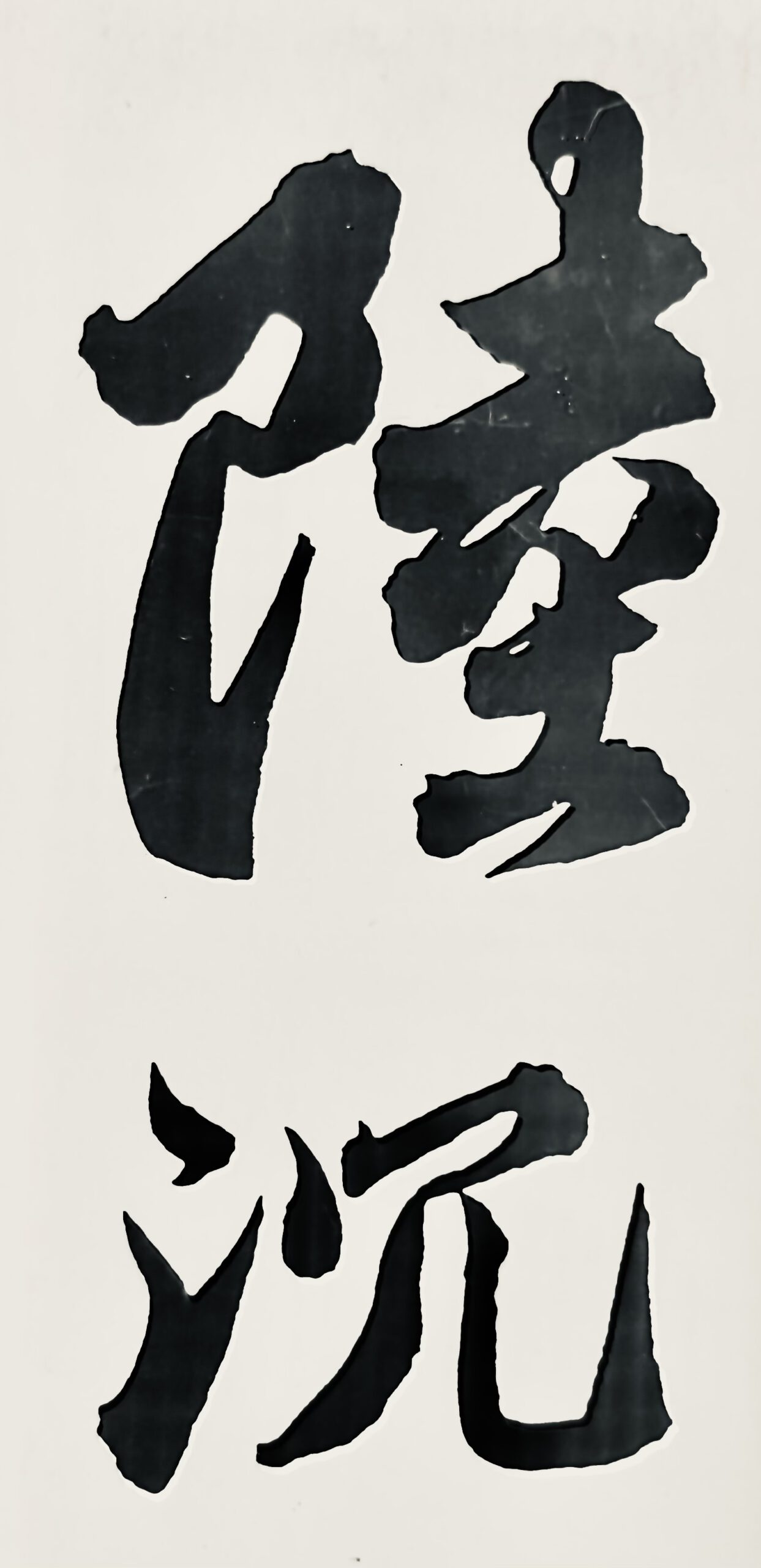

In Part One, ‘Swallowed Up’ 陸沉, we feature Dai Qing’s defense of her work in the face of criticisms made of Tiananmen Follies, a collection of her post-1989 essays, published by Jonathan Mirsky in the pages of the New York Review of Books in 2005. Part Two, ‘At Eights & Nines’ 不如意事常八九,可與言者無二三, introduces Deng Xiaoping in 1989 鄧小平在1989, a revised edition of Dai Qing’s account of the tumultuous events of 1989 and the mindset of Mao’s successor, published by Bouden House 博登書屋 in New York in April 2024.

We are grateful to Dai Qing and Wang Xiaojia for their contribution to this commemoration and to Samuel C. George, a China Heritage Research Fellow, for editing and translating material related to Dai Qing’s new book. My thanks, as ever, to Reader #1, for looking through the draft of this piece. All remaining errors are my own.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

4 June 2024

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

Part One 陸沉

Part Two 八九

- At Eights & Nines

- Spectres of Chinese Communist Culture

- Deng Xiaoping Addresses the PLA

- Deng Xiaoping in 1989

- Deng & His Legacy — an Iron Fist in a Velvet Glove

Appendix

***

Dai Qing in China Heritage:

- Celebrating Dai Qing at Eighty, 1 October 2021

- Commemorating a Different Centenary — Dai Qing on the 1911 Revolution, 12 October 2021

- On China’s “Rise” and the Environment’s Decline — Celebrating Dai Qing at Eighty, 22 October 2021

- Dai Qing, Stefan Zweig & the Victory of the Defeated, China Heritage, 30 December 2021

Select Material from 1989 to 2023:

- On the Eve — China ’89 Symposium, Bolinas, California, 27-29 April 1989

- Simon Leys, After the Massacres, The New York Review of Books, 12 October 1989

- He Xin, A Word of Advice to the Politburo, The Australian Journal of Chinese Affairs, January 1990

- Beijing Days, Beijing Nights, May 1989, 1991

- Using the Past to Save the Present: Dai Qing’s Historiographical Dissent, East Asian History, vol.1 (June 1991): 141-181

- Geremie Barmé & Linda Jaivin, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992

- The Gate of Heavenly Peace, Boston: Long Bow, 1995

- Chai Ling Sues the Long Bow Group, 2009-2013

- 1989, 1999, 2009: Totalitarian Nostalgia, China Heritage Quarterly, June 2009

- The Gate of Darkness, 4 June 2017

- Mourning Liu Xiaobo, 30 June 2017

- Memory Holes, old & new, 29 May 2017

- Geremie R. Barmé, Supping with a Long Spoon — dinner with Premier Li, November 1988, 10 December 2018

- Liu Xiaobo, Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, 24 January 2019

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, et al, In Memoriam — 4 June 2021, 4 June 2021

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Jeremy Brown, June Fourth: The Tiananmen Protests and Beijing Massacre of 1989, Cambridge University Press, 2021

- Julian Gewirtz, Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s, Harvard, 2022

- Geremie R. Barmé, A Decade of Telling Chinese Stories, 1 May 2022

- Back When the Sino-US Cold War Began, 1 June 2023

- Mike Chinoy, Covering Tiananmen, an excerpt from ‘Assignment China’, ChinaFile, 2 June 2023

Material Related to June 1989 published in June 2024:

- Jianying Zha, The Habit of Hoping, China Books Review, 30 May 2024

- ChinaFile, 35 Years Later: A Retrospective of Our Work on the 1989 Tiananmen Protests and Crackdown, ChinaFile, 3 June 2024

- 最後的秘密——中共十三屆四中全會「六四」結論文檔,香港:新世紀出版及傳媒有限公司,2019年5月, re-released in May 2024

- Yangyang Cheng, Grieving Tiananmen as US Cops Crush Campus Protests, The Nation, 3 June 2024

- 江雪,六四35年的紀念:從六四紀念館到白紙運動,歪腦 WHYNOT,2024年6月3日 (for a translation of this material, see Alexander Boyd, Memories of a Massacre: Recollections of June Fourth Beyond Beijing, China Digital Times, 5 June 2014)

- William Farris, On How Internet Companies Censor 1989, X, 4 June 2024

- Lingua Sinica, Keeping the Memory of June Fourth Alive, Substack, 4 June 2024

- Alex Colville, Talking Tiananmen with a Chinese Chatbot, China Media Project, 4 June 2024

***

Swallowed Up

陸沉

Former People, Бывшие люди (Byvshiye lyudi), is the title of a novella by Maxim Gorky published in 1897. Known in English translation as Creatures That Once Were Men, Gorky’s story would inspire the Bolsheviks to employ the term ‘Former People’ when speaking about survivors of the defunct ancien regime. Their number included members of the aristocracy, the clergy, the Tsarist military and bureaucracy. As individuals whom the progress of history had cast aside, Former People were treated as ‘has-beens’ in every regard.

I had the good fortune to be befriended by a number of China’s Former People from just after the death of Mao Zedong in late 1976. As many of those men and women were gradually recognised as now being members of ‘The People’ during the early post-Mao years, I would also come to know others who were well on the way to joining the ranks of a whole new category of China’s Former People.

— G.R. Barmé, from the introduction to Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People, 13 July 2020

***

Dai Qing, reporter, civilian historian, novelist, editor, is a major figure in China’s pantheon of Former People. The Beijing Massacre of June Fourth 1989 and the nationwide purge that followed in its wake saw her relegated to obscurity. Cast into China’s Memory Hole, her best-selling work on the Communist Party’s hidden history, her feminist activism and her outspoken advocacy in support of China’s then nascent environmental movement, were all swept away by state-engineered forgetfulness. Long banned from speaking to the international media and discriminated against by overseas Chinese political activists and commentators alike because of her family connections and controversial views, Dai Qing is one of China’s most annoying non-people. Now in her eighties, she refuses to keep quiet.

***

I arrived in Beijing on 7 May 1989. A newly minted PhD with a postdoctoral fellowship at The Australian National University in Canberra, I was on something of a Pacific tour. It had started in late April, when I attended China ’89 Symposium in Bolinas, California, from 27-29 April. Organized by Orville Schell, Liu Baifang, and Hong Huang with the support of The New York Review of Books, the Symposium was envisaged as providing a forum for a number of leading Chinese intellectuals and cultural figures, both from Mainland China and Taiwan, to discuss the state of the state and their view of China’s future with academics and journalists from the United States (plus one rogue academic/ writer from Australia). As things turned out, the Symposium took place during one of the early high points of the student protests of 1989.

After Bolinas I participated in a conference marking the seventieth anniversary of the May Fourth Movement of 1919. The theme of my paper was China’s Velvet Prison, a topic that I had first written about in 1988, and my presentation opened with a discussion of Washing in Public 洗澡, a novel by Yang Jiang 楊絳 published in late 1988 that tells a story of unrequited love against the backdrop of the ideological reeducation of Chinese intellectuals in the early 1950s.

I had known Yang since the early 1980s and, after Taipei — where, on 4 May I celebrated my thirty-fifth birthday — I travelled to Beijing via Hong Kong to present her with a new and expanded edition of my translation of her Cultural Revolution memoir that had just been published in Australia under the title Lost in the Crowd (Melbourne: McPhee Gribble, 1989). I had chosen the ancient expression ‘swallowed up by the earth’ 陸沉 lù chén as the Chinese title of the book and, at my request, Qian Zhongshu 錢鍾書, Yang’s scholar husband, had written the two characters of the title for the book’s cover.

[Note: 陸沉 lù chén occurs in Zhuangzi: 方且與世違而心不屑與之俱,是陸沈者也。(《莊子·則陽》), which Guo Xiang 郭象 glosses as 人中隱者,譬無水而沈也。]

In visiting Beijing I planned both to ask Yang Jiang to grant me permission to translate Washing in Public and to seek out another Chinese writer to discuss a research project based on her historical work. That writer was Dai Qing and I hoped to interview her about the celebrated, and controversial, political portraits that she had written of Liang Shuming, Wang Shiwei and, most recently, Chu Anping (see The Party Empire).

By the time I arrived in Beijing, the city was in open revolt. Although I managed to discuss my plans with Yang Jiang, Dai Qing was embroiled in the protests. Over the years, her interviews and research had led her to be wary of clamorous political activism and, although she was sympathetic with the popular rebellion, she was also convinced that anti-reformist elements in the Party were actively manipulating the protests not only to shut down the economic reforms but to block any chance that China might embark upon a course of systemic and political reform that, like their authoritarian brethren in Taiwan, might enable the country finally to transition towards a more open and equitable future. Her efforts to convince protesters to leave the square before it was too late were, as she knew all too well, doomed to be futile, just as her warnings about the dark future were ignored. In a phone conversation we had on the first day of the mass student hunger strike, she observed that youthful firebrands would play into the hands of the conservatives and make compromise with more conciliatory members of the government impossible. Events proved that she was right to be fearful and her fateful predictions proved to be more correct than even she could have imagined.

Although we remained in contact until early June, we did not manage to sit down to discuss her work on excavating Party history until August 1990, some months after she was released from custody (for details, see Using the Past to Save the Present: Dai Qing’s Historiographical Dissent). By then, Dai Qing herself had been ‘swallowed up by the earth’.

***

Banned and ignored in China for 35 years, Dai Qing, a best-selling author of non-official history in the 1980s, is even overlooked today by those who work on China’s frustrated civil society and its underground historians. Falling between competing narratives and ideologies, her voice has been effectively lost. Even so, she has refused to remain silent and despite constant police intimidation and threats she has managed over the decades to write, speak out and challenge the system when and where she can.

We should be mindful of the fact that for nearly two decades, Liu Xiaobo was also a non-person, not only in the People’s Republic, but also among many international Chinese commentators and pro-democracy activists. He had been despised by many of their number even before he returned to Beijing in April 1989, and he was hated for having gone on the record to say that, as one of the last people to leave Tiananmen Square on the morning of 4 June, he had not seen anyone killed on the Square itself. This should have put paid to student leader Chai Ling’s tearful confection about ‘rivers of blood’ in Tiananmen, but only his activism in 2008, his subsequent jailing and his status as a Nobel Laureate could redeem Xiaobo’s reputation.

[Note: For more on this topic, see the details of Chai Ling’s attempts to sue the Long Bow Group, of which I am a member, over the documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace, as well as Totalitarian Nostalgia, China’s Promise and ‘Ironic Points of Light’ — acts of redemption on the blank pages of history.]

One of the ironies of 1989 is that, for all the talk of democracy, free speech and openness, individuals who expressed views that dissented both from the official Chinese mainstream and the collective wisdom of oppositionists, derision, denial and displeasure tended to be the order of the day. It brings an old expression to mind: everyone is allowed to be different, in exactly the same way.

On this the thirty-fifth anniversary of the Beijing Massacre, I recall the injustices meted out to Dai Qing and to Liu Xiaobo, both in- and outside of the People’s Republic of China.

[Note: See also Dai Qing, Stefan Zweig & the Victory of the Defeated, China Heritage, 30 December 2021.]

***

International journalists, diplomats and some academics offered crucial accounts of the events of 1989 both at the time and in retrospect. Some of their number interpreted what they saw and heard in ways that were in stark contrast to my own understanding of the unfolding events and their ‘deep structure’ in Chinese politics and culture.

Jonathan Mirsky (1932-2021) was an energetic chronicler of events in Beijing which, added to his long-term involvement with China, gave him a strong sense of being on ‘the right side of history’. Many people in many climes and at many times have a similar appreciation of themselves. My own understanding is based more on doubt and skepticism, both of what Official China says about itself, as well as of the claims of Dissident China.

By all rights, I should have been a fan of Mirsky’s writing. I enjoyed many of the reports, reviews and essays that he wrote; but in the 1990s and early 2000s, as a member of a clutch of writers who tended to dominate the pages of the The New York Review of Books, The New Yorker, The New York Times and various other publications, his single-minded and often reductionist views were less appealing.

I first met Jonathan in Torino, Italy, when I was working with my old classmate Marco Müller on his retrospective of Chinese cinema in February 1982. I encountered Dai Qing in Beijing the following year. Nearly a quarter of a century later, we enjoyed a moment of triangulation. The details of that ‘encounter’ follow below.

— GRB

***

See also:

- Ian Buruma, The Beginning of the End, New York Review of Books, 21 December 1995; and,

- Carma Hinton and Richard Gordon (with Geremie Barmé), Response to The Beginning of the End, 9 May 1996, and Buruma’s reply

Tiananmen Follies: An Exchange

Dai Qing, with Geremie R. Barmé,

and a reply by Jonathan Mirsky

April 27, 2006

In response to:

China: The Uses of Fear from the October 6, 2005 issue (for Mirsky’s original review, see the Appendix below)

To the Editors:

In his review of the English translation of my prison writings, Tiananmen Follies, Jonathan Mirsky [NYR, October 6, 2005] makes a number of claims in relation to my work and my public stance both prior to, and since, the Beijing Massacre of June 4, 1989, that call for some comment.

Based on his reading of Tiananmen Follies, Mr. Mirsky reaches two conclusions. The first is that the Communist Party authorities employed the same methods of emotional torture and terror in dealing with those incarcerated as a result of the 1989 Tiananmen incident as they did during the Yanan “rescue movement” of the 1940s. Secondly, he avers that in 1990s China such methods were still effective, or at least they proved to be so in the case of the author of that book, that is to say, myself. As a result Mr. Mirsky claims that while I wrote some worthy things in the past, following my imprisonment I was cowed into abandoning my former beliefs.

The truth about me is quite the contrary. Even though I had been on a list in prison of people slated to be executed, I remained determined throughout that ordeal to stick to my convictions. When I was released from prison in 1990 I gave an interview to a foreign journalist in which I declared, for publication around the world, that “you could say about my release that they’ve let me out of a small prison into a massive jail.” I have continued to speak and write in a forthright fashion ever since my release—on the environmental dangers China faces, on the sensitive issue of repression in the Chinese Communist Party’s history, and on a wide range of equally sensitive topics. As a consequence, at one point I was placed under house detention, and at another I was exiled to Hainan Island in the extreme south of China.

In his response to the letter to the editors from Geremie R. Barmé and Jonathan Unger published by The New York Review [November 17, 2005 [see below]], Mr. Mirsky repeats his earlier claims against me and expresses a wish to hear directly from me. Well, I have the following to say:

In his response Mr. Mirsky remarked that “the Three Gorges essays, as I pointed out, were excellent, but were written before her time in prison.” He attempts to demonstrate that I have been frightened into silence. Surely, this is at odds with the facts.

Prior to my imprisonment I produced only one book related to the Three Gorges Dam, the edited volume Changjiang, Changjiang (Nanning: Guizhou Renmin Chubanshe, 1989). Following my release from jail, I edited another work, Shuide Changjiang (literally, “Who Owns the Yangtze?”), a book that appeared in Chinese in 1993 through Oxford University Press in Hong Kong. The English version of that work was published in 1996 under the title The River Dragon Has Come.

In relation to my public opposition to the Three Gorges project, for example, I would have thought that any reader of Chinese with an interest in my work, or for that matter a concern for the environmental fate of China, would have easily been able to find the numerous essays that I have published in the mainstream international Chinese press and on the Internet since 1992.

Furthermore, for over a decade I have given speeches, keynote addresses, and talks relating to the Three Gorges Dam in many countries, although on one such occasion, in Vietnam, my speech was canceled at the last minute due to official Chinese government pressure. My most recent engagement with this issue was in October 2005. I was able to make a public speech in Beijing for the first time in some fifteen years at Sanwei Bookstore on Chang’an Avenue, Central Beijing. My talk was entitled “The Three Gorges and the Environment.” The Chinese transcript of that speech was posted on the Web for a week before being deleted by the authorities. However, both the English and Chinese versions of my remarks are readily accessible internationally on the Internet.

In regard to my engagement with other controversial issues of moment, I repeat here what I said on the tenth anniversary of Tiananmen at a commemorative symposium held at the John King Fairbank Center of Harvard University on May 13, 1999. I told my audience that:

I have lost my voice in China; I have lost my true audience, my supporters and critics in China; and I have been deprived of a chance for open and direct public engagement with my world. Yet although I have been thus diminished, I have not given up hope. Nor have I given in to the fashionable opinions and simplistic caricatures of China that prevail, both in China itself and here in America.

In China I have refused to mouth the government lies about 1989; I will not uncritically sing the praises of the power-holders and what they have done during these ten years.

And here, in America, I won’t parrot the simple slogans and extreme rhetoric that so much of the US media delights in. I refuse to play the simple-minded dissident; I refuse to give in to the thoughtless stereotypes that so many public figures in this country pursue when talking about China; I won’t follow the crude claims of some critics that unless you mount a direct and provocative challenge to the Communist Party, you are nothing less than a toady to the power-holders.

In my own limited way I want still to write and speak of the vast, complex, and rapidly changing realities of China.

In his response to Barmé and Unger’s letter to the editors, Mr. Mirsky expressed some regret that the editors of Tiananmen Follies had failed to ask me whether I still stood by “some of the things she said in the book.” I presume he is referring to passages that I wrote in prison such as the following:

Would it have been possible with a certain timely control to keep the Beijing student movement from turning chaotic in the streets between April and June of 1989? The answer is yes. If, at any time during the end of April, early May, mid-May (when the hunger strike began), and late May (once martial law was established), the government in power had really intended to put an end to the movement and had ordered the students and city residents to leave the streets, it would not have been difficult. But without such action, it is quite natural that matters escalated rapidly, because two kinds of people wanted the protest to escalate in the hope that some people would die and the protest might then turn into an “incident” of some magnitude.

Do I still hold to these views? Yes. I maintain the view that by declaring a hunger strike on May 13, 1989, the student leaders contributed to a precipitous escalation of a situation that, until then, might have been defused. The relatively open-minded faction of power-holders who were in the public eye and who had been charged with dealing with the protests were now put in a very difficult position. From the perspective of Deng Xiaoping, the paramount power-holder, these developments were proof that the “reformist faction” was incapable of containing the situation, and therefore it would no longer enjoy his confidence.

Mr. Mirsky is convinced that any talk of there being a “black hand working behind the scenes” is nothing more than a repetition of a government calumny, one aimed against the intellectuals who supported the students. He hasn’t managed to work out what I, writing in jail and faced with the prospect of death, was saying in my prison writings: that the people who hoped that the situation would spiral out of control were the factional opponents of Zhao Ziyang. As for the student leaders themselves, I believe that their problem was their youthful rashness.

Seventeen years have passed since the events of 1989, and it is clearly evident today how profoundly the value system and thought processes inculcated by Mao Zedong have beguiled generation after generation of China’s young people. Take Chai Ling for example, the activist who famously said that what her group of student leaders were “actually hoping for is bloodshed” on the eve of June 4, 1989 (yes, Mr. Mirsky, the word Chai Ling uses in Chinese, qidai [期待], does mean “look forward to” or “hope for”). People show their true colors in extreme situations, and Chai Ling proved to be a good student of Chairman Mao’s. Furthermore, there were others who really did hope that the hunger-striking students would stay in the square. Various factions among the power-holders reasoned that if they did so they could be used as political pawns during the National People’s Congress that was soon to be held.

As to my evaluation of the question “Who benefited and who lost out?” as a result of the massacre of June 4, 1989, I would say that perhaps even Deng Xiaoping himself did not want to see such an outcome. This is because there were indications in China at the time that he was actually planning to speed up the process of political reform, a process that had long been bogged down. Indeed, shortly before the Tiananmen demonstrations erupted, I was present when Wang Feng, the head of the Taiwan office of the Party’s Central Committee and one of Deng Xiaoping’s intimates, remarked that “Comrade Xiaoping is actively considering removing the Four Basic Principles from the Constitution and having them limited to the Party Constitution.” The Four Basic Principles, it should be recalled, were introduced in February 1979 at the time of de-Maoification, and they were used to maintain ideological rectitude during the years of economic reform that followed. They were like a Sword of Damocles that hung over the heads of people, forcing people to conform to the Party’s norms. Such a decision to remove the Four Basic Principles from the Constitution would have augured a major development in the political reform of China, just as a similar act by Mikhail Gorbachev in the Soviet Union had signaled a major political transformation in that country.

Those who got the most out of the situation were the political opponents of Zhao Ziyang, who hoped to force him and his associates from power, as well as those members of the nomenklatura, that is, the Party gentry, who enjoyed all the privileges afforded by the monolithic state created under the conditions of the “proletarian dictatorship.”

To this day I say, as I wrote then in prison, that I “support the martial law order issued on May 20, 1989, and support the army implementing it immediately.” I would emphasize to Mr. Mirsky that martial law was declared on May 20, but it was not implemented immediately. Indeed, the weeks between the declaration and the final tragedy of June 3–4 saw the further unfolding of a complex political drama involving internal Party factions and the manipulation of restive mass and student opinion.

The question I ask in Tiananmen Follies is: Weren’t the authorities willfully allowing the situation to get out of hand? Weren’t they manipulating things so that they could undermine the reformers who were in favor of using martial law as a way of restoring order, reformers who were anxious that things not spiral out of control? If martial law could have been imposed quickly, the power-holders in favor of democratization would have been able to shepherd their forces and make a comeback at some time in the future.

In his review, Mr. Mirsky was also particularly disdainful of my remark that the students should have been satisfied with the government’s concession that henceforth the authorities would no longer hold party meetings at the seaside resort of Beidaihe, or avail themselves of imported luxury vehicles. I still believe that squeezing such a concession out of the Party at the time was a big victory for the protesters. Over the years, the Party had proved itself to be extraordinarily reluctant to relinquish any of the perquisites of power. And, after all, Mr. Mirsky may recall that in my work on the early Yanan-era dissenter Wang Shiwei, which he avows to admire, I outlined that one of the reasons for the denunciation (and the eventual beheading) of Wang was that he had the temerity to question the special food and clothing allowances the Party leaders gave themselves at a time of supposed egalitarian frugality.

As for my “confessions” in jail, Mr. Mirsky declares himself to be particularly offended by my references to “Chairman Mao” and “ideological method,” as well as my confession’s promise not to get involved in political issues in the future. Of course, I wrote this in my confession; my life was at stake. It is ironic that having weathered the interrogations of the Communists, years later I am subjected to the intemperate declamations of a reviewer who has so obviously misread my book. Well, Mr. Mirsky, I’d like to spell it out for you: I was using my “confessions” to explicate my position, and to announce my innocence. The vast majority of these written statements were laden with diversionary tactics, or commonplace irony, “slipping away under the cover of a big coat,” as we say. These are all devices with which the average Chinese reader is completely familiar. I also used the Party’s language to make fun of it.

Of course, I should acknowledge Mr. Mirsky’s detestation of communism and note his sympathy for the Chinese people. However, if he presumes to have anything of value to say regarding the complex and confusingly intricate realities of China, I would suggest that he’ll have to work quite a bit harder. All right, if his Chinese isn’t quite up to the task, he could always have spared a few minutes Googling my name in English. At least in that way he could have avoided making the most elementary mistakes regarding my work. Or, if his Chinese was equal to it, over these many years he could have read at least a few of the many dozens of articles I have written for a worldwide Chinese-language audience, essays that touch on a wide range of subjects related to his own interests in contemporary Chinese politics, culture, society, life, and civil liberties.

Anti-Communist sloganizing does nothing so much as mirror the kind of mentality favored by Mao and Kang Sheng during the 1942 rectification campaign. Mr. Mirsky praised me for exposing the horrors of that campaign to the world. The mentality of that campaign has played an invidious role in Chinese politics and life ever since the 1940s. It is, I’m afraid, a mentality that has been shared by many others. In the end, extremist and simplistic ideologies express themselves in the same strident fashion, only the wording differs. While one chants “Chairman Mao is our savior!,” the other shouts “Mao Zedong is a monster!”

Dai Qing, with Geremie R. Barmé

Beijing

***

Jonathan Mirsky replies:

In Dai Qing and Geremie Barmé’s letter criticizing my review of Ms. Dai’s book, Tiananmen Follies, there is much material on what she has done since her release from prison in 1990. My review, however, was of her book, which is devoted to her arrest and her time in prison. She thought well enough of these materials to publish them under her name.

When I was preparing my review I sent a list of questions to the editors. Did she still stand by what she had written? Were there, for example, “black hands” behind Tiananmen? Ms. Dai still says flatly that there were. Does she really believe that the Beijing “black hands” were behind the other four hundred uprisings throughout China that spring? She says I should have been able to “work out” what she really meant. She could easily have made this plain in her book, but, one of her editors explained, “while a general reader might need a longer introduction I don’t think this book calls for one. Anyway, Dai Qing didn’t want one.”

I sent the editors a final draft of my review to check for factual errors. This was the response: “review looks good, reads well, no surprises…Sullivan team [i.e., the book’s editors] not unhappy or displeased.”

The key matter here is her confession. I asked the editors, “Is the confession real or just something she was forced to say. In the introduction it says she is no ‘snitch’ but she is, and she shows plenty of remorse, though it is said she doesn’t.” So was it real or was it staged, and if staged is this obvious? Ms. Dai now says: “I was using my ‘confessions’ to explicate my position, and to announce my innocence. The vast majority of these written statements were laden with diversionary tactics, or commonplace irony, ‘slipping away under the cover of a big coat,’ as we say. These are all devices with which the average Chinese reader is completely familiar. I also used the Party’s language to make fun of it.”

Does that mean that the—rare—footnote in Ms. Dai’s book on her confession is false? In it she says, “I had told the truth and nothing but the truth, mainly because this would make things much easier and more convenient. This, I believe, was something that left a profound impression on the minds of the comrades of the special case group [her interrogators].”

On the book jacket, in words I presume were approved or written by Dai Qing or the editors, it says of her confession that it is “at times quite unflattering to the author…. She begins to accept the government’s view on certain matters, ending up fingering others in a manner that suggests previous collaborationist actions in China.”

So whether the confession is true, as she emphasizes in the book, or was really “slipping away under the cover of a big coat,” Ms. Dai misled her publisher, her editor, and me. She must take responsibility for her text, which contains the words about which I wrote my review.

***

Source:

- Tiananmen Follies: An Exchange, NYR, 27 April 2006

The Case of Dai Qing

To the Editors:

In a review of the prison memoirs of the Chinese writer and dissident Dai Qing [“China: The Uses of Fear,” NYR, October 6 [2005]], Jonathan Mirsky wrote that after her post-Tiananmen release Dai Qing’s “writing about the regime then took a different turn” and that “fear seems to explain the sad transformation in her writing,…jettisoning a lifetime’s convictions.”

We would like to set the record straight. As China specialists who have personally known Dai Qing for a long time and who keep abreast of her prolific writings, we can affirm that she did not jettison her convictions. Indeed, she remains one of the most courageous, controversial figures on the Chinese cultural and intellectual scene today.

In the years since her release from prison in 1990, Dai Qing has been a persistent proponent of freedom of speech and a critic of censorship. She has also gained an international reputation as one of China’s staunchest environmentalists. Her energetic work against China’s gigantic Three Gorges Dam has deservedly won her awards from environmental organizations around the world. For this and other courageous public efforts, she has been under house arrest more than once.

She has kept up a constant flow of writing, translating, and editing on a wide range of topics despite her work being banned in China. Under a variety of pen names (and also through essays published in Hong Kong and Taiwan and on the Chinese Internet), she continues to lambast cant and political hypocrisy in a uniquely powerful writing style that uses delicate sarcasm and irony to withering effect. Jonathan Mirsky is an admirer of her earlier writings, and he will be happy to know that she has lost none of her polemical vigor.

On an important point, both Mirsky and we ourselves disagree with a political view held by Dai Qing. She does not believe that China is ready for democracy—that is, multiparty elections to select China’s leadership. She has long been convinced that without a lengthy period of independent publishers, a decent education system, and a large, well-educated middle class, any democratic vote in China would be fatally undermined by demagoguery and corruption. She believes that until the conditions for democracy are ripe, China would be better off under an increasingly relaxed Party rule. She expressed such sentiments in her prison writings—which Mirsky presumed was a sell-out of her convictions. What he does not realize is that Dai Qing expressed such a view in writings published prior to the Tiananmen protests, just as (consistent to a fault) she holds fast to such an opinion in conversations and in her essays today.

This does not make her a toady or friend of the Party. What Dai Qing above all will be remembered for is her well-researched, truly extraordinary studies of the darker side of Communist Party history. Mirsky admiringly notes her writings in this vein from the 1980s. Again, he will be glad to know that Dai Qing continues to write and when possible publish major essays and books that dissect and confront important past episodes of Party repression, with scarcely concealed lessons for today.

In short, Dai Qing has not been scared into submission and has not betrayed her ideals. She has remained a true, effective, courageous dissenter, contrary to the impression Mirsky gained from her prison memoirs. She deserves to have this erroneous impression corrected in The New York Review’s pages.

Geremie Barmé

Jonathan Unger

The Australian National University

Canberra, Australia

***

Jonathan Mirsky replies:

I did not say Dai Qing had sold out. I said she was terrified into making the statements she includes in her book. I was also, as they say, careful to write at some length that until 1989 she did great work for freedom of expression. The Three Gorges essays, as I pointed out, were excellent, but were written before her time in prison. Neither in the book’s introduction nor in the edited material is this made nearly as plain as I wrote in my review.

I said that Dai Qing’s editors should have asked her if she still believed some of the things she said in the book. She called the Tiananmen demonstrations a conspiracy caused by a mastermind, “the one,” whom she never names, while also saying he had used as a mouthpiece the admirable dissident Wang Dan, who served seven years in prison after Tiananmen. She said she regretted condemning the troops for entering the square and stated that “I support the announcement of martial law and propose that the martial law troops carry out the order immediately.” This is precisely what happened.

Mr. Unger and Mr. Barmé, both well-respected China specialists, do not deal with what Dai Qing actually says in her book. They have told me they were unable to read it because almost all the copies were destroyed in a fire at the publisher’s. I am happy to learn that Dai Qing has resumed her libertarian work, but she has done herself a great disservice in Tiananmen Follies and would do well to write to the Review herself and say what she now believes. Does she still claim, as she does in the book, that she wrote “recklessly without much real thought or careful consideration…. It was exactly the kind of erroneous style of thinking that our Chairman Mao once criticized…”? Does she still promise “never again [to] involve myself with political issues nor express opinions on important matters, especially since I am no longer a Party member”?

Does she still say she acted “out of pure emotion and irrationality” and that “deep down in my heart I had forgotten all the responsibility [of being a Party member]…to protect the reputation of the government above anything else”?

I wrote that few people would have been able to stand up to what happened to her in Qin Cheng prison; any critical comment on her book should be seen in that light. But her statements in Tiananmen Follies are all the more in need of clarification following the letter of Mr. Barmé and Mr. Unger.

***

Source:

- The Case of Dai Qing, NYR, 17 November 2005

***

When Dai Qing and I met up again at her apartment at Furongli near Peking University, in April 1991, to continue the conversation the we had begun in May 1989, she handed me a thick envelope. It contained dozens of name cards; they belonged to China’s new Former People — men and women, in the Party, the government, academia, publishing, the arts and business — who had been variously jailed, demoted, persecuted or forced into exile as a result of June Fourth 1989. Of course, the pile also included Dai Qing’s own defunct name card and her job title: ‘Guangming Daily journalist’.

For details of our ensuing conversation, see Using the Past to Save the Present: Dai Qing’s Historiographical Dissent, East Asian History, vol.1 (June 1991): 141-181.

— GRB

***

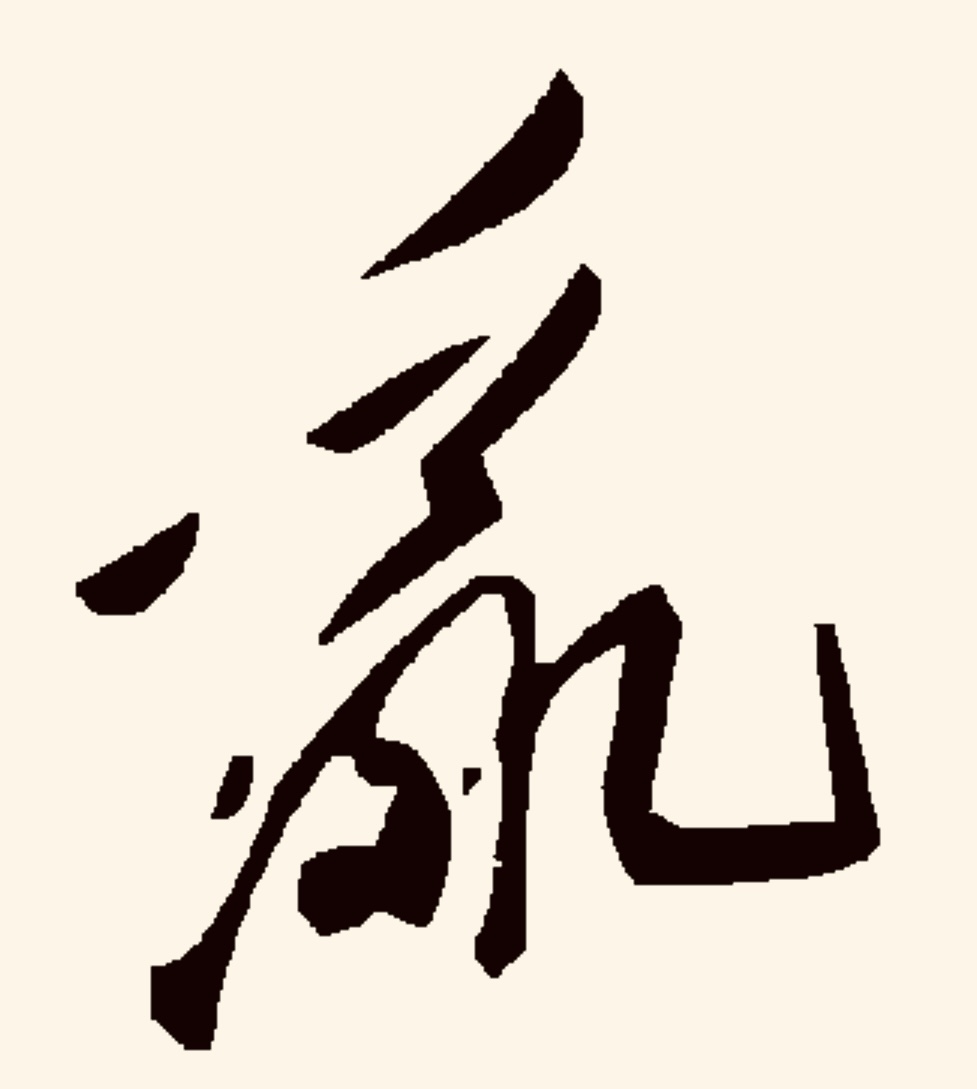

At Eights & Nines

不如意事常八九

可與言者無二三

Some of the following material previously appeared in Back When the Sino-US Cold War Began, 1 June 2023.

***

This storm was bound to come sooner or later. This is determined by the major international climate and China’s own minor climate. It was bound to happen and is independent of man’s will. It was just a matter of time and scale.

這場風波遲早要來。這是國際的大氣候和中國自己的小氣候所決定了的,是一定要來的,是不以人們的意志為轉移的,只不過是遲早的問題,大小的問題。

Deng Xiaoping made this statement when addressing leaders of the PLA five days after they had imposed martial law by force of arms on the Chinese capital on 4 June 1989.

Deng’s speech reaffirmed the message of the front-page Editorial published by the People’s Daily on 26 April 1989, at the beginning of what would be six weeks of unrest in Beijing and dozens of other Chinese cities. That editorial, written on the basis of the directives of Deng and his elderly comrades, had been broadcast on the evening of 25 April and was published the following day.

The Editorial declared that student-led protests sparked by the death of former Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang were actually led by a secretive group — ‘an extremely small number of people’ — who were fomenting ‘turmoil’ 動亂 dòngluàn ‘to sow dissension among the people, plunge the whole country into chaos and sabotage the political situation of stability and unity. This is a planned conspiracy and a disturbance. Its essence is to, once and for all, negate the leadership of the CPC and the socialist system.’

Talk of a secretive cabal engaged in a conspiracy to ‘once and for all negate’ the Party harked back to dark warnings about foreign interference in Chinese affairs that dated back to 1949 and which had been repeated on numerous occasions, not only during the Mao-Liu era (1949-1978) but throughout the first decade of the Open Door and Economic Reform (1978-1988).

In his remarks on 9 June 1989, Deng reiterated and expanded on the message of the 26 April Editorial when he said that:

The incident became very clear as soon as it broke out. They have two main slogans: One is to topple the Communist Party, and the other is to overthrow the socialist system. Their goal is to establish a totally Western-dependent bourgeois republic. The people want to combat corruption. This, of course, we accept. We should also take the so-called anticorruption slogans raised by people with ulterior motives as good advice and accept them accordingly. Of course, these slogans are just a front: The heart of these slogans is to topple the Communist Party and overthrow the socialist system. …

In declaring that the aim of the backstage managers of the 1989 protests was to overthrow the Communist Party and turn China into ‘a totally Western-dependent bourgeois republic’ 一個完全西方附庸化的資產階級共和國, Deng acknowledged a decades-long conflict. By publicly identifying the plot against China, first on 26 April and again on 9 June 1989, Deng Xiaoping warned of the scale and significance of China’s clash with the US-led Western order. (For more on the historical context of this contestation, see We Need to Talk About Totalitarianism, Again.) And, when years later, China was encouraged to become ‘responsible stake-holder’ in the ‘international rules-based order’ under the aegis of America, Deng’s remarks about the danger of the People’s Republic ending up as a ‘Western-dependent bourgeois republic’ resonated again.

Deng had repeatedly warned against Western values, political ideas and cultural infiltration since early 1979. Advised by Party thinkers like Hu Qiaomu and with the support of a coterie of Mao-era colleagues, in 1979 Deng declared that ‘to achieve the Four Modernizations it is imperative to adhere to the Four Cardinal Principles in the realm of ideology. These principles are:

- Adherence to the socialist road;

- Adherence to the dictatorship of the proletariat;

- Adherence to the leadership of the Communist Party; and

- Adherence to Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.’

‘As you all know,’ Deng told Party members, ‘none of these principles are new; our Party has been resolutely adhering to them all along.’ In June 1989, Deng would remark:

There is nothing wrong with the Four Cardinal Principles. If there is anything amiss, it is that these principles have not been thoroughly implemented: They have not been used as the basic concept to educate the people, educate the students, and educate all the cadres and Communist Party members.

The nature of the current incident is basically the confrontation between the Four Cardinal Principles and Bourgeois Liberalization. It is not that we have not talked about such things as the Four Cardinal Principles, work on political concepts, opposition to Bourgeois Liberalization, and opposition to Spiritual Pollution. What we have not had is continuity in these talks, and there has been no action — or even that there has been hardly any talk.

Although the Four Principles had been written into the Chinese constitution in June 1979 and were imposed during a series fitful of ideological and cultural purges (see, for example, The View from Maple Bridge, Part I, 5 February 2023), Deng and his colleagues were also cautious not to let the pursuit of ideological purity interfere with their desperately ambitious economic policies.

Following the destructive Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign of late 1983, Deng had even called for an embargo on ideological wrangling for three years. However, student protests in Shanghai, calls for media freedom and democracy in late 1986, put a momentary end to that spate of liberalisation. The subsequent purge of Party leader Hu Yaobang and prominent Party members presaged the denouement of 1989.

In Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, a culture-focussed account of post-Mao China published in 1986 and expanded in 1988, we chronicled Deng’s repeated warnings and suggested that further clashes between Party ideology and the social forces encouraged by China’s open door and reform policies were inevitable. Our account was also informed by the skepticism of leading Hong Kong critics of Beijing, independent thinkers in China itself and famously insightful writers like Simon Leys. Nonetheless, I found my own bleak view of events repeatedly dismissed by a raft of diplomats, journalists and academics who preferred a narrow and simplistic view of Deng Xiaoping’s economic pragmatism instead of undertaking the hard work to appreciate the ways in which Party ideology not only shaped policy but offered a holistic worldview and means by which China’s power holders made sense of themselves and the world.

In November 1988, between courses at the state dinner held for Chinese Premier Li Peng by the Australian Prime Minister Bob Hawke, I suggested that the power struggle between Li and Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang — a topic of white-hot speculation both in- and outside China — was, for all intents and purposes, resolved. All that remained was social upheaval and the denouement. Before long, Zhao would indeed take the fall for Beijing’s economic missteps, the Party’s ideological drift and even China’s social anomie. (See Supping with a Long Spoon — dinner with Premier Li, November 1988). The consequences of Zhao Ziyang’s fall proved to be cataclysmic and we are still living with the aftermath of those momentous events.

***

In June 1989, Deng had unerringly identified the reason why, with the exception of Zhao Ziyang and some of his younger colleagues, the Communist Party’s leaders had been unified in their approach to the ‘turmoil’ of 1989. ‘What is most advantageous to us’, Deng said,

is that we have a large group of veteran comrades who are still alive. They have experienced many storms and they know what is at stake. They support the use of resolute action to counter the rebellion. Although some comrades may not understand this for a while, they will eventually understand this and support the decision of the Central Committee.

It was this group of elders — the Eight Gerontocrats 八大元老 — a coterie of Mao-era Party bosses who had ruled China from 1949 up to the mid 1960s with draconian ferocity, who proved to be the key to the Communist Party’s post-Mao political stability and systemic intransigence. Even as China had launched an ambitious program of reform from 1978, the Party gentry, which had tentacles and connections of fealty that extended to every corner of China, jealously protected the privileges of their caste and the vision that justified it. Having reluctantly contemplated late-Soviet-like constitutional reform (see Dai Qing, 《鄧小平在1989》 and Dai Qing at Eighty), the Elders remained true to form in framing 1989 as part of a decades-long Cold War. They felt further justified by the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991 (when, as Xi Jinping put it decades later, no ‘real man’ had defended the cause in Moscow) and they were reassured that the Cold War had never really ended. Soon, the threat of ‘peaceful evolution’ — a multi-pronged strategy of ‘The West’ dating from the 1950s to white-ant Party rule — was back on the agenda, and everything from ideas to colour revolutions would be framed as inimical. As we argued in Prelude to a Restoration, Xi Jinping is heir to the legacy of the Eight Gerontocrats.

[Note: For more on this topic, see:

- Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold;

- You Should Look Back; and,

- 1978-1979, Year One of the Xi Jinping Crisis with the West.]

***

Was there a coordinated attempt to stir up public discord and manipulate mass unrest to overthrow the Communist party-state and replace it with a western-style economic satrapy in 1989? The widespread sense of anomie in Chinese society, frustrations arising from rampant corruption, influence peddling and the secretive activities of the Party gentry, along with anxieties among workers about the influence of quasi-capitalist reformist policies were the handiwork of the Communist Party itself. If and how others hoped to take advantage of a national mood of disquiet and restlessness, and to what end, remains a matter for speculation. There seems little doubt that the on-again/ off-again ideological Cold War of post-Mao China coupled with economic policies that benefitted all parties worked well enough until Xi Jinping, a real Cold Warrior born of the Maoist era, took the helm. (See ‘Ξ — The Xi Variant’ in You Should Look Back.)

Spectres of Chinese Communist Culture

Following the banquet with Mikhail Gorbachev during which a dumpling slipped through Deng Xiaoping’s chopsticks and he seemed disoriented, some demonstrators depicted Deng as an addled ruler akin to the Cixi Empress Dowager who ‘ruled from behind the bamboo screen’ 垂簾聽政 chuí lián tīng zhèng during of the late-Qing dynasty.

***

On the Eve — China ’89 Symposium was held in Bolinas, California, on 27-29 April, 1989. Organized by Orville Schell, Liu Baifang, and Hong Huang with the support of The New York Review of Books, the Symposium was envisaged as providing a forum for a number of leading Chinese intellectuals and cultural figures, both from Mainland China and Taiwan, to discuss the state of the state and their view of China’s future with academics and journalists from the United States (plus one rogue academic/ writer from Australia).

As things turned out, the Symposium took place during one of the high points of the student protests of 1989. The lengthy recorded tapes of the discussions at the symposium were transcribed. The editorial process was completed during 1991 and the material was published on the website of The Gate of Heavenly Peace, a documentary film released in 1995.

I made the following observations during the first session of the Symposium on the morning of 27 April 1989. (See also You Can Get Here from There — Soviet historian Stephen Kotkin on Xi Jinping’s China — Watching China Watching (XL), China Heritage, 9 May 2023.)

***

On Chinese Communist Culture

Geremie Barmé

27 April 1989

I would like to raise the question of “communist culture”, this is, the special culture created under communist rule. It is a matter of world-wide relevance, and much has been written on the subject, especially in Eastern Europe, touching on Soviet, Hungarian, and Polish communist culture. But Chinese intellectuals have a predilection for talking about their traditional culture and are loath to discuss the phenomenon of Chinese communist culture. Perhaps they have yet to appreciate that it exists.

Just now Ge Yang commented on China having emulated the Soviet model. Similarly, Wang Ruowang wrote after being expelled from the Communist Party two years ago that the problem confronting China is not one of traditional culture, nor a dilemma about how to “take the best from both East and West”, but a problem of Sovietization.

The fact remains that today China’s political culture is primarily Stalinist. This is a question that has not received the attention it deserves. At our forum several people have repeated a sentiment seen often in the Chinese press: political reforms have made little headway. Why? Because the Stalinist model remains in place. The nature of Deng Xiaoping’s rule, the rhetoric of the People’s Daily, and so many other things all attest to this fact. The machinery of the Proletarian Dictatorship is still intact and can be put into operation at any time. Yesterday the government refrained from unleashing this machine, but this is not proof that the students have won. Deng, being the practiced politician that he is, doesn’t want to let the students capitalize on the anniversary of May Fourth or on Gorbachev’s visit. Deng will feign tolerance until Gorbachev leaves Beijing, and will then use force to clean up the mess. He would be a patent fool to do otherwise.

In recent years, Chinese intellectuals have made little effort to study Eastern Europe with an eye to comparisons with their own situation. Instead much attention is paid to the countries that, in their eyes, represent “modern international standards” — in particular the United States and then France and Japan. To try to emulate such nations is a pipedream. China would do much better to look to the Eastern Bloc, for example the Soviet Union or Hungary, for a solution to its predicament. It would be a tremendous achievement if China could emulate Hungary; if China were now to “learn from the Soviet Union”, as it did in the 1950s, it might indeed have a “radiant future”.

Equally, it is futile for China to attempt to revive “traditional culture”, as if its communist history had never occurred. Communist culture is a fact of life, whether you like it or not. But there is a new interpretation of things in China.

Recently, at a meeting held for some Hungarian delegation, Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang said that China cannot emulate the democratization process that is proceeding in the Soviet Union, because this would not be in keeping with China’s “national characteristics” (guoqing). Isn’t that marvelous! According to the People’s Daily, Li Peng made a similarly absurd remark just a few days ago. But just what are China’s “national characteristics”? A central feature of Chinese reality is its domination by a Soviet-style machine. If the Eastern European style of reform doesn’t suit China, what ever will? But then the Chinese are only interested in discussing “democracy” with Americans or Frenchmen. They don’t want to have a dialogue with Poles or Hungarians. They don’t even know what’s going on in those countries. The head of Solidarity recently said he would not run for the presidency of the country. What a luxury! Who in China — which head of which union — could be so magnanimous? Why doesn’t China care to learn from them?

[At this point the moderator, Liang Congjie, interjected: “Don’t forget that the students named their organization ‘Solidarity Students’ Union’. This shows at least some Eastern European influence!”]

But to return to the topic of today’s panel, “What is worth retaining from traditional or Maoist culture?” It is interesting that this issue is so often posed as a question. The implication seems to be that someone — or some social class or group, perhaps — can actually decide what China should retain or discard. But is this possible? Mao Zedong appears to have tried and failed. Can any of the present political incumbents, or even the intellectuals, do any better? I feel we should question the way this topic itself is conceived.

I would like to conclude with what I think is a revealing little anecdote. It’s a story that touches on something which we in the West have drummed into us from youth: the relationship between means and ends.

My wife, who is in Beijing, tells me that a friend of ours observed an incident that occurred among the serried ranks of students marching toward Tiananmen Square. They were in neat columns, having organized themselves according to school, department and class. Their very organization exhibited “communist culture” — the same patterns initially used by Red Guards in the early stages of the Cultural Revolution. They even chorused the same slogans and sang the same theme song — “The Internationale”. They carried posters with a uniform message. Their stated goal was “democracy”, but they hardly appeared to be an army marching for democracy. Behind this force trailed a scruffy crowd of long-haired arty types and others from art and film schools. This slovenly bunch didn’t march in line, nor did they sing the prescribed songs or chant the proper slogans. Embarrassed by this unseemly eyesore, the student leaders angrily demanded that the mob of stragglers either conform or not march at all.

It’s food for thought, isn’t it?

[Note: A decade later, I expanded on these ideas in Totalitarian Nostalgia, the twelfth and final chapter in my book In the Red: on contemporary Chinese culture, New York: Columbia University Press 1999, pp.316-344.]

***

Deng Xiaoping Addresses the PLA

9 June 1989

Deng Xiaoping’s ‘Speech Made While Receiving Cadres of the Martial Law Units in the Capital at and Above the Army Level’, read by an announcer during the Chinese evening news on 27 June 1989.

Comrades, you have been working very hard. First, I express my profound condolences to the commanders and fighters of the People’s Liberation Army [PLA], commanders and fighters of the armed police force, and public security officers and men who died a heroic death; my cordial sympathy to the several thousand commanders and fighters of the PLA, commanders and fighters of the armed police force, and public security officers and men who were injured in this struggle; and cordial regards to all commanders and fighters of the PLA, commanders and fighters of the armed police force, and public security officers and men who took part in this struggle. I propose that we all rise and stand in silent tribute to the martyrs.

I would like to take this opportunity to say a few words.

This storm was bound to come sooner or later. This is determined by the major international climate and China’s own minor climate. It was bound to happen and is independent of man’s will. It was just a matter of time and scale. It is more to our advantage that this happened today. What is most advantageous to us is that we have a large group of veteran comrades who are still alive. They have experienced many storms and they know what is at stake. They support the use of resolute action to counter the rebellion. Although some comrades may not understand this for a while, they will eventually understand this and support the decision of the Central Committee.

The April 26 Renmin Ribao editorial ascertained the nature of the problem as that of turmoil. The word turmoil is appropriate. This is the very word to which some people object and which they want to change. What has happened shows that this judgment was correct. It was also inevitable that the situation would further develop into a counterrevolutionary rebellion.

We still have a group of veteran comrades who are alive. We also have core cadres who took part in the revolution at various times, and in the army as well. Therefore, the fact that the incident broke out today has made it easier to handle.

The main difficulty in handling this incident has been that we have never experienced such a situation before, where a handful of bad people mixed with so many young students and onlookers. For a while we could not distinguish them, and as a result, it was difficult for us to be certain of the correct action that we should take. If we had not had the support of so many veteran party comrades, it would have been difficult even to ascertain the nature of the incident.

Some comrades do not understand the nature of the problem. They think it is simply a question of how to treat the masses. Actually, what we face is not simply ordinary people who are unable to distinguish between right and wrong. We also face a rebellious clique and a large number of the dregs of society, who want to topple our country and overthrow our party. This is the essence of the problem. Failing to understand this fundamental issue means failing to understand the nature of the incident. I believe that after serious work, we can win the support of the overwhelming majority of comrades within the party concerning the nature of the incident and its handling.

The incident became very clear as soon as it broke out. They have two main slogans: One is to topple the Communist Party, and the other is to overthrow the socialist system. Their goal is to establish a totally Western-dependent bourgeois republic. The people want to combat corruption. This, of course, we accept. We should also take the so-called anticorruption slogans raised by people with ulterior motives as good advice and accept them accordingly. Of course, these slogans are just a front: The heart of these slogans is to topple the Communist Party and overthrow the socialist system.

In the course of quelling this rebellion, many of our comrades were injured or even sacrificed their lives. Their weapons were also taken from them. Why was this? It also was because bad people mingled with the good, which made it difficult to take the drastic measures we should take.

Handling this matter amounted to a very severe political test for our army, and what happened shows that our PLA passed muster. If we had used tanks to roll across [bodies?], it would have created a confusion of fact and fiction across the country. That is why I have to thank the PLA commanders and fighters for using this attitude to deal with the rebellion. Even though the losses are regrettable, this has enabled us to win over the people and made it possible for those people who can’t tell right from wrong to change their viewpoint. This has made it possible for everyone to see for themselves what kind of people the PLA are, whether there was a bloodbath at Tiananmen, and who were the people who shed blood.

Once this question is cleared up, we can seize the initiative. Although it is very saddening to have sacrificed so many comrades, if the course of the incident is analyzed objectively, people cannot but recognize that the PLA are the sons and brothers of the people. This will also help the people to understand the measures we used in the course of the struggle. In the future, the PLA will have the people’s support for whatever measures it takes to deal with whatever problem it faces. I would like to add here that in the future we must never again let people take away our weapons.

All in all, this was a test, and we passed. Even though there are not very many senior comrades in the army and the fighters are mostly children of 18 or 19 years of age — or a little more than 20 years old — they are still genuine soldiers of the people. In the face of danger to their lives, they did not forget the people, the teachings of the party, and the interests of the country. They were resolute in the face of death. It’s not an exaggeration to say that they sacrificed themselves like heroes and died martyrs’ deaths.

When I talked about passing muster, I was referring to the fact that the army is still the People’s Army and that it is qualified to be so characterized. This army still maintains the traditions of our old Red Army. What they crossed this time was in the true sense of the expression a political barrier, a threshold of life and death. This was not easy. This shows that the People’s Army is truly a great wall of iron and steel of the party and state. This shows that no matter how heavy our losses, the army, under the leadership of the party, will always remain the defender of the country, the defender of socialism, and the defender of the public interest. They are a most lovable people. At the same time, we should never forget how cruel our enemies are. We should have not one bit of forgiveness for them.

The fact that this incident broke out as it did is very worthy of our pondering. It prompts us cool-headedly to consider the past and the future. Perhaps this bad thing will enable us to go ahead with reform and the open policy at a steadier and better — even a faster — pace, more speedily correct our mistakes, and better develop our strong points. Today I cannot elaborate here. I only want to raise a point.

The first question is: Are the line, principles and policies adopted by the third plenary session of the Eleventh CPC Central Committee, including our three-step development strategy, correct? Is it the case that because of this rebellion the correctness of the line, principles, and policies we have laid down will be called into question? Are our goals leftist ones? Should we continue to use them as the goals for our struggle in the future? We must have clear and definite answers to these important questions.

We have already accomplished our first goal, doubling the GNP. We plan to take twelve years to attain our second goal of again doubling the GNP. In the next fifty years we hope to reach the level of a moderately developed nation. A 2 to 2.9 percent annual growth rate is sufficient. This is our strategic goal.

Concerning this, I think that what we have arrived at is not a “leftist” judgment. Nor have we laid down an overly ambitious goal. That is why, in answering the first question, we cannot say that, at least up to now, we have failed in the strategic goals we laid down. After sixty-one years, a country with 1.5 billion people will have reached the level of a moderately developed nation. This would be an unbeatable achievement. We should be able to realize this goal. It cannot be said that our strategic goal is wrong because this happened.

The second question is: Is the general conclusion of the Thirteenth Party Congress of one center, two basic points correct? Are the two basic points — upholding the four cardinal principles and persisting in the open policy and reforms — wrong?

In recent days, I have pondered these two points. No, we have not been wrong. There is nothing wrong with the four cardinal principles. If there is anything amiss, it is that these principles have not been thoroughly implemented: They have not been used as the basic concept to educate the people, educate the students, and educate all the cadres and Communist Party members.

The nature of the current incident is basically the confrontation between the four cardinal principles and bourgeois liberalization. It is not that we have not talked about such things as the four cardinal principles, work on political concepts, opposition to bourgeois liberalization, and opposition to spiritual pollution. What we have not had is continuity in these talks, and there has been no action — or even that there has been hardly any talk.

What is wrong does not lie in the four cardinal principles themselves, but in wavering in upholding these principles, and in very poor work in persisting with political work and education.

In my CPPCC talk on New Year’s Day in 1980, I talked about four guarantees, one of which was the enterprising spirit in hard struggle and plain living. Hard struggle and plain living are our traditions. From now on we should firmly grasp education in plain living, and we should grasp it for the next sixty to seventy years. The more developed our country becomes, the more important it is to grasp the enterprising spirit in plain living. Promoting the enterprising spirit in plain living will also be helpful toward overcoming corruption.

After the founding of the People’s Republic, we promoted the enterprising spirit in plain living. Later on, when life became a little better, we promoted spending more, leading to waste everywhere. This, together with lapses in theoretical work and an incomplete legal system, resulted in breaches of the law and corruption.

I once told foreigners that our worst omission of the past ten years was in education. What I meant was political education, and this does not apply to schools and young students alone, but to the masses as a whole. We have not said much about plain living and enterprising spirit, about the country China is now and how it is going to turn out. This has been our biggest omission.

Is our basic concept of reform and openness wrong? No. Without reform and openness, how could we have what we have today? There has been a fairly good rise in the people’s standard of living in the past ten years, and it may be said that we have moved one stage further. The positive results of ten years of reforms and opening to the outside world must be properly assessed, even though such issues as inflation emerged. Naturally, in carrying out our reform and opening our country to the outside world, bad influences from the West are bound to enter our country, but we have never underestimated such influences.

In the early 1980s, when we established special economic zones, I told our Guangdong comrades that they should conduct a two-pronged policy: On the one hand, they should persevere in reforms and openness, and the other they should severely deal with economic crimes, including conducting ideological-political work. This is the doctrine that everything has two aspects.

However, looking back today, it appears that there were obvious inadequacies. On the one hand, we have been fairly tough, but on the other we have been fairly soft. As a result, there hasn’t been proper coordination. Being reminded of these inadequacies would help us formulate future policies. Furthermore, we must continue to persist in integrating a planned economy with a market economy. There cannot be any change in this policy. In practical work we can place more emphasis on planning in the adjustment period. At other times, there can be a little more market regulation, so as to allow more flexibility. The future policy should still be an integration of a planned economy and a market economy.

What is important is that we should never change China into a closed country. There is not [now?] even a good flow of information. Nowadays, do we not talk about the importance of information? Certainly, it is important. If one who is involved in management doesn’t have information, he is no better than a man whose nose is blocked and whose ears and eyes are shut. We should never again go back to the old days of trampling the economy to death. I put forward this proposal for the Standing Committee’s consideration. This is also a fairly urgent problem, a problem we’ll have to deal with sooner or later.

This is the summation of our work in the past decade: Our basic proposals, ranging from our development strategy to principles and policies, including reform and opening to the outside world, are correct. If there is any inadequacy to talk about, then I should say our reforms and openness have not proceeded well enough.

The problems we face in the course of reform are far greater than those we encounter in opening our country to the outside world. In reform of the political system, we can affirm one point: We will persist in implementing the system of people’s congresses rather than the American system of the separation of three powers. In fact, not all Western countries have adopted the American system of the separation of three powers.

America has criticized us for suppressing students. In handling its internal student strikes and unrest, didn’t America mobilize police and troops, arrest people, and shed blood? They are suppressing students and the people, but we are quelling a counterrevolutionary rebellion. What qualifications do they have to criticize us? From now on, we should pay attention when handling such problems. As soon as a trend emerges, we should not allow it to spread.

What do we do from now on? I would say that we should continue to implement the basic line, principles, and policies we have already formulated. We will continue to implement them unswervingly. Except where there is a need to alter a word or phrase here and there, there should be no change in the basic line and basic principles and policies. Now that I have raised this question, I would like you all to consider it thoroughly.

As to how to implement these policies, such as in the areas of investment, the manipulation of capital, and so on, I am in favor of putting the emphasis on basic industry and agriculture. Basic industry includes the raw material industry, transportation, and energy. There should be more investment in this area, and we should persist in this for ten to twenty years, even if it involves debts. In a way, this is also openness. We need to be bold in this respect. There cannot be serious mistakes. We should work for more electricity, more railway lines, more public roads, and more shipping. There’s a lot we can do. As for steel, foreigners think we’ll need some 120 million metric tons in the future. We are now capable of producing about 60 million metric tons, about half that amount. If we were to improve our existing facilities and increase production by 20 million metric tons, we would reduce the amount of steel we need to import. Obtaining foreign loans to improve this area is also an aspect of reform and openness. The question now confronting us is not whether or not the reform and open policies are correct or whether we should continue with these policies. The question is how to carry out these policies: Where do we go and which area should we concentrate on?

We must resolutely implement the series of line, principles, and policies formulated since the third plenary session of the Eleventh CPC Central Committee. We should conscientiously sum up our experiences, persevere with what is correct, correct what is wrong, and do a bit more where we have lagged behind. In short, we should sum up the experiences of the present and look forward to the future.

***

Source:

- Beijing Domestic Television Service, 27 June 1989; FBIS (Foreign Broadcast Information Service), 27 June, pp.8-10. For the Chinese text, see 在接見首都戒嚴部隊軍以上幹部時的講話

***

Deng Xiaoping in 1989

戴晴著《鄧小平在1989》,2024年版

Below, Dai Qing introduces her book on the events of 1989. This is followed by a short note by Wang Xiaojia, her daughter and academic collaborator, edited and translated by Samuel George, a Research Fellow at China Heritage.

***

On my book

Dai Qing

This is a long-considered text that draws both on my personal experience of the events of 1989 as well as subsequent investigation as an investigative journalist. Although I have had limited access both to archival and other published material, I have been able interview participants in those events who, after three decades, were finally willing to speak about them. The second edition of the book, published five years after the first edition in 2019, contains further relevant material and even the names of some of my interview subjects who were willing to ‘go public’. Others preferred to retain their anonymity.

What is, I believe, novel about my approach is that my narrative is not driven by the activities of the protesting students or events on Tiananmen Square. I also avoid the simple black-and-white dichotomies common in many [predominantly Chinese-language] works on the period published over the decades in which autocracy is pitted against democracy and the authorities are lumped together in a stand off with the students. Neither group was homogeneous.

Deng Xiaoping in 1989 tells of a ‘red China’ that, in the ongoing process of its transformation into a modern nation, remained riven by factional strife and ideological contestations. This ultimately led to the tragic and bloody denouement of 4 June 1989.

Tragedy, I must observe, has been a wind that has long filled the sails of Chinese civilisation. Be it in the imperial era, or under Mao, repeated tragedies have marked our history. New tragedies marked the era of Deng Xiaoping, be they of the leaders, or of new historical actors in the realm of intellectual life, among business people and within the student protesters, among whom at ever turn, radicals won out over moderates.

I am confident that Deng Xiaoping in 1989 will be of some use to future generations who will continue the quest to explore and understand our past and China’s place in the world. It offers the material that I have amassed here as well as an endless series of questions.

— trans. GRB

***

Deng & His Legacy — an Iron Fist in a Velvet Glove

Wang Xiaojia on Dai Qing &

Dai Qing on Deng Xiaoping

edited and translated by Samuel C. George

Thirty-five years have passed since the massacre of 4 June 1989. Although Dai Qing enjoyed a celebrated career during the 1980s, during which time she rose to become China’s most famous, and controversial, investigative journalist, the Beijing protest movement of April-June 1989, and the fateful day of 4 June have determined the course of her life ever since. Over the decades, she has been subject to the Party’s control, endured ‘social death’ and been forced to live with the total negation of her public role. Aware that her efforts are in vain, she has continued to write undaunted. She has told me that unless she persisted in exposing the Party’s hidden truths and finding ways to express her anger at the injustices inflicted on China under its rule she simply would not be able to face herself.

One result of her efforts is Deng Xiaoping in 1989, a revised edition of which appeared with an independent Chinese-language publishing house in New York in May 2024.

In Deng Xiaoping in 1989, Dai Qing disentangles two intertwined threads from the messy skein of events leading up to 4 June. One is a visible, more immediately obvious thread — the timeline leading up to June Fourth and the Beijing Massacre itself which has been a focal point for scholars and commentators for years. The other thread, one hidden and obscure, is the story germane to Communist Party rule. Central to this is the character of Deng Xiaoping himself.

As Dai Qing observes, the blood-soaked mechanism of a revolutionary system such as that of China presents us with a paradox and the obvious often obscures darker realities. This is as true for the Communist rulers as it is for their avowed opponents. During the 1989 protests, for example, even as the call for freedom, democracy and the rule of law resonated with countless protesters, a revolutionary zealotry that mirrored that of the Communists was willing to use whatever means, even the most violent, to achieve its ends. Some even believed that only when Tiananmen Square itself was awash in blood would people then awaken to the true nature of the Communist Party.