Viral Alarm

The following poem was composed by Li Xueyuan, a calligrapher based in Wuhan, Hubei province. It started circulating online in the early hours of Saturday, the 19th of September, a week after the Beijing police had announced that Geng Xiaonan and her husband Qin Zhen had been taken into custody and were being questioned in relation to what they called ‘illegal business activities’.

In this poem the author amplifies on a theme that we noted in Ai Xiaoming’s poetic lament for Geng Xiaonan (see ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Dance of Defiance’). Here the poet directly addresses those — mostly men — who have for years enjoyed the unstinting hospitality, support and activities organised by Geng Xiaonan. By means of a range of historical, literary and political references, the poet asks why have all of those celebrated public figures fallen silent now that Geng is in need of their support.

Allow me to repeat the observation Ai Xiaoming made in the interview she gave to Ian Johnson in 2016:

‘…in the past perhaps I believed in the goodness of human nature. I believe this is naïve. Actually, human nature in this totalitarian society has become very vile. This power has changed Chinese people’s psychological makeup. Most people, very many people, are really terrible; they’re afraid of losing things. I don’t mean ordinary people. In fact, ordinary people are often quite clear about the system. I mean, a lot of people in universities, a lot of intellectuals, they know. But the pressure is so great. A lot of people don’t want to sacrifice because being inside the system has a lot of advantages. Why would they want to give up such a comfortable life?’

As I noted in January 2010, following the sentencing of Liu Xiaobo for his participation in the Charter 08 calls for political reform in China:

‘… leading Chinese thinkers condemned a decision that was obviously politically motivated, an abuse of legal norms and another indication that the Party-state is fearful of reasoned and legitimate opposition to autocratic rule. The Chinese media could not report their views, but they are available on Twitter. In January 2010, for instance, an unofficial (and in China unpublishable) poll of leading thinkers, rights activists, lawyers and writers, was unanimous in condemning the absurd charges against Liu and the harsh sentence meted out to him by the Party-dominated legal system. …

‘I would note in passing that in Cui [Weiping]’s list of some ninety Chinese thinkers, it would appear that those with a more avowedly “left-leaning” cast (that is those who generally provide some kind of academic and intellectual rationale for Party-state dominance albeit in the guise of Euro-American neo-Marxism), seem uncharacteristically at a loss for words. Indeed, even the most enthusiastic advocates of the regnant Party-state blather inanities and bromides when confronted with the kind of pitiless political and intellectual censorship as evinced in the case of Liu Xiaobo.’

— from Geremie R. Barmé, ‘China’s Promise’

China Heritage Quarterly, March 2010

Over the years, and in particular since the irresistible rise of Xi Jinping and the quelling of intellectual, media and social activism, support for those who would speak out, like Xu Zhiyong and Xu Zhangrun, to name but two prominent figures, has dwindled.

The reasons for such reticence are understandable, but here our poet takes issue with the cowardice of what in China are known as ‘wine-and-meat buddies’ 酒肉朋友, that is those who repeatedly enjoyed her largesse in the past, in other words fair-weather friends. One of their number, when pressed to show some support for the detained publishers, offered gnomically: 吉人自有天相, ‘I’ll leave it up to Fate’. It’s a statement somewhat akin to saying: ‘Let them jail whomsoever they want; God will work it out.’ This is a recasting of the famous declaration made during the Albigensian Crusade in 1209: ‘Caedite eos. Novit enim Dominus qui sunt eius’ (Kill them all. The Lord knows those who are his own).

Charter 08 was a high-point in the story of post-1989 collective and principled opposition to the one-party state. Xu Zhangrun’s rebellion from 2016, the support he garnered along the way, and the recent fate of Geng Xiaonan, are a further phase in the recurrence and repression of direct civic resistance to Xi Jinping’s ‘New Epoch’. There is no telling when further outbreaks of independent action, collective protest or rebellion may occur. One thing, however, is certain: they are inevitable.

John Minford and I named our collection of contemporary Chinese writing published in Hong Kong in 1986 Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience. The title was inspired by a line from Lu Xun, written in December 1935:

‘As long as there shall be stones, the seeds of fire will not die.’

石在,火種是不會絕的。

As we noted in our introduction to that volume, Lu Xun observed that:

‘good literature always refuses orders from outside—it never cares about the consequences, it springs spontaneously from the heart’… He summed up the relationship between the writers and the revolution (he was talking of the Soviet experience) in the following words: ‘During the era of revolution, writers have a dream in which they imagine how beautiful the world will be after the success of the revolution. But when the revolution has succeeded, they find things entirely different from their dream. Hence they have to suffer again. They cry out but will not succeed in their protests. They cannot succeed by going either forward or backward. It is their destiny to witness the inconsistency between ideal and reality.’

***

Here we offer Li Xueyuan’s original poem, followed by a bilingual version which in turn is followed by an annotated version of the text.

The draft of Li’s poem was titled ‘Mulan’ 木蘭 and the first line read: ‘古之木蘭,奏凱而還’ (Of yore Mulan returned to celebrated victory). Even though the version of the poem that Li Xueyuan decided to circulate was untitled, in light of the international media kerfuffle surrounding the Disney film Mulan in September 2020, and the rekindled interest in that legendary female warrior, I have chosen to call this chapter in Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020 ‘Geng Mulan — reading a poem for a hero’. It is also offered as another ‘Lesson in New Sinology’.

Readers interested in the ‘Ballad of Mulan’ 木蘭辭, written in the Northern Wei period (386-535 CE), and the treatment of the story of Mulan in the eponymous Disney film, may wish to consult:

- James Millward, ‘Mulan: More Hun than Han’, China Channel, 25 September 2020

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

26 September 2020

***

On Geng Xiaonan:

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Xu Zhangrun: I Am Compelled to Speak Out in Defence of Geng Xiaonan’, China Heritage, 24 September 2020

- The Editor & Bei Ming 北明, ‘The Kafkaesque Trials of Geng Xiaonan’, China Heritage, 20 September 2020

- Ai Xiaoming 艾曉明, ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Dance of Defiance’, China Heritage, 16 September 2020

- Bei Ming, 北明, ‘A Chinese Decembrist and Professor Xu Zhangrun’, China Heritage, 10 September 2020

Other Annotated Translations in the Xu Zhangrun Archive:

- ‘And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!’, China Heritage, 10 November 2018

- ‘To Summon a Wandering Soul’, China Heritage, 28 November 2018

- ‘Humble Recognition, Boundless Possibility — Part I’, China Heritage, 31 January 2019

- ‘The State of a Civilisation — Humble Recognition, Boundless Possibility, Part II’, China Heritage, 8 March 2019

***

A Prefatory Note

The following poem is written in a modern semi-literary ‘Book of Songs style’ 詩經體. Each line is made up of eight character-words and a relatively consistent rhyme pattern is used throughout. Among other devices employed herein, the poet plays on the meanings of the syllables of Geng Xiaonan’s name:

- 耿 gěng: decent; concerned, perturbed, glistening;

- 瀟 xiāo: the rustling of wind or susurration; and,

- 男 nán: male, man, masculine, forthright.

— GRB

***

《無題》

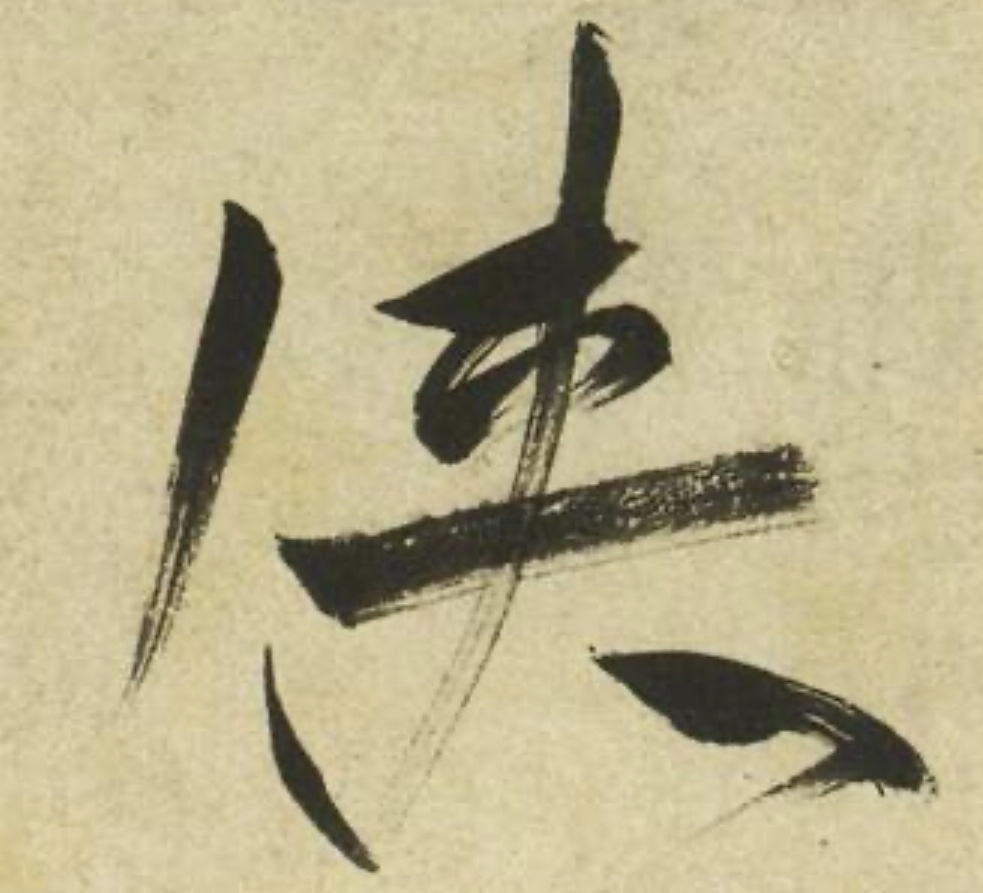

李雪原

耿介之士,出自梨園

瀟瀟劍氣,折煞兒男

家國有事,豈可旁觀

塵埃一粒,其重如山

有彼君子,不懼危安

直言捅天,俠肝義膽

又有俠女,牽馬扶鞍

亦步亦趨,挺身擋彈

眾聲消歇,怒不敢言

川女血性,焉做寒蟬

歲月靜好,不過裝酣

心系蒼生,一往無前

為眾抱薪,今遭風雪

嗟爾士子,嚅嚅囁囁

便車常搭,汝心可安

君子落難,圍觀聲援

撐我雨傘,遮君風寒

耿耿星河,曙光在前

瀟瀟秋雨,漫漫長夜

男兒奮起,齊討兇頑

***

***

Untitled

《無題》

Li Xueyuan

李雪原

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

This principled person may come from the ‘Pear Garden’ of theatre

But the swathes described by her steely actions outrage those imposter men

耿介之士,出自梨園

瀟瀟劍氣,折煞兒男

With the nation beleaguered thus, how could she stand idly by?

Every mote of trouble pressed down on her, weighty as a mountain

家國有事,豈可旁觀

塵埃一粒,其重如山

And that gentlemen, too, undaunted by any fear for his weal or woe

Unleashed his pointed works shaking the very heavens; valor true, cause righteous

有彼君子,不懼危安

直言捅天,俠肝義膽

Supported by this woman warrior, she leading steeds and offering comfort

Following closely in his wake, using her body to shield against outrageous fortune

又有俠女,牽馬扶鞍

亦步亦趨,挺身擋彈

The clamorous have suddenly fallen silent, swallowing their anger

Confronted by this spirited Sichuan Lady, how can they flinch in winter’s cold

眾聲消歇,怒不敢言

川女血性,焉做寒蟬

Your pretend security and heedless comfort is but a counterfeit pose

Those ones devoted to vast humanity’s cause continue on, determined

歲月靜好,不過裝酣

心系蒼生,一往無前

You enjoyed her generous support, but now she is battered by the tempest

Yet you, Fine Gentlemen — you hold back in obnoxious cowardice

為眾抱薪,今遭風雪

嗟爾士子,嚅嚅囁囁

You long enjoyed the free ride, can you really live with yourselves now?

Those outstanding are in trouble, gather round and raise your voices

便車常搭,汝心可安

君子落難,圍觀聲援

I will hold high my umbrella, may it shield her against the bitter gales

Hers is shining example amidst a multitude of stars revealing the dawn ahead

撐我雨傘,遮君風寒

耿耿星河,曙光在前

The autumn rains are relentless and a long night lies ahead

But those possessed of macho valor must surely stir

And together challenge those obdurate dementors

瀟瀟秋雨,漫漫長夜

男兒奮起,齊討兇頑

***

***

Annotated Translation

The following notes offer an explanation of the most obvious meanings of the words and expression used in Li Xueyuan’s poem. Many are well known, others are slightly more oblique, references to the living ‘literary-historical-intellectual’ traditions with which students of the Chinese world should seek to become acquainted. Annotated words or phrases are underlined.

— Geremie R. Barmé

***

耿介之士,出自梨園

瀟瀟劍氣,折煞兒男

This principled person may come from the ‘Pear Garden’ of theatre

But the swathes described by her steely actions outrage those imposter men

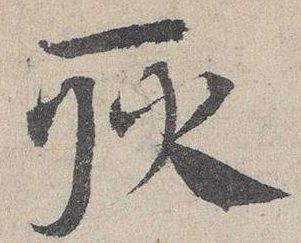

耿介 gěng jiè: ‘outstanding and unwavering’, ‘glorious and great’, ‘honest and upright’. This term appears in ‘Li sao: On Encountering Trouble’, attributed to Qu Yuan, where it is used to extol the legendary emperors Yao and Shun:

Glorious and great were those two, Yao and Shun,

Because they had kept their fee on the right path.彼堯、舜之耿介兮,既遵道而得路。

— 屈原《离骚》, trans. David Hawkes

The Songs of the South, 1985, p.69

士 shì: a decent person or someone of principle. In his essays, Xu Zhangrun has frequently quoted or referred to the line ‘The refusal of one decent man outweighs the acquiescence of the multitude’ 千人之諾諾,不如一士之諤諤。It comes from ‘The Biography of Lord Shang’ in Sima Qian’s Records of the Grand Historian《史記 · 商君列傳》。The line features as the untranslated epigraph of The Chairman’s New Clothes, the famous critique of the Cultural Revolution published by Simon Leys in 1971.

Geng Xiaonan herself summed up Xu Zhangrun’s personality with the words: ‘he is, above all, a 士 shì, a “literatus” ‘. She went on to say:

‘Chinese people are familiar enough with the word 士 shì, after all everyone comes across it from an early age. But, let me ask you and your listeners: you may have heard about the 士 shì of the past, but have you ever actually encountered one in the present? My guess is that the vast majority of Chinese people simply have no idea what a living 士 shì might really be like. But I can proudly say that I do, and that’s because I know Xu Zhangrun. He answers to the definition of 士 shì in that, for me, in his person he combines “intellectual excellence” with the accomplishments of a “public intellectual” and the virtues of a “model citizen of the Republic”.’

— Bei Ming, ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Insights into The World of Xu Zhangrun (Part I)’

For more on the word-concept 士 shì as it relates to Xu Zhangrun, see:

- Bai Xin 白信, ‘Tsinghua’s War with Tradition — How a Chinese University Decoupled Itself from its Better Angels, Again’, China Heritage, 6 August 2020; and,

- Feng Chongyi 馮崇義, ‘A Scholar’s Virtus & the Hubris of the Dragon’, China Heritage, 22 May 2019

梨園 Lí Yuán: a garden favoured by Ming Huang (Emperor Xuanzong) of the Tang dynasty where he is said to have enjoyed various entertainments. Over time, the Pear Garden — known for its numerous fruit trees — became the site of theatrical diversions supported by imperial patronage. Since that time, ‘Pear Garden’ has referred to various entertainments, in particular opera, and those associated with the theatre. We would note that, thereafter, those started out in the ‘Pear Garden’ were often regarded contemptuously as mere theatricals.

瀟瀟 xiāo xiāo: here ‘xiao xiao’ refers to the swoosh of a sword wielded by a martial arts hero. Below this metaphor is taken up when Geng is referred to as a ‘woman warrior’ 俠女 or 女俠. The theme of the brave woman putting men to shame runs through the poem, something emphasised by the use of the word 男 nán, as in 兒男, 男兒, 瀟男。

劍氣 jiàn qì: an expression used in martial arts fiction that refers to the particular ‘energy of the sword’, something that, when the sword is wielded by a righteous person reflects the 真氣 zhēn qì or ‘primal energy’ that courses through the universe. 劍氣 jiàn qì makes the weapon one of devastating force that can smite enemies at a distance.

折煞 zhé shà: to frustrate, undo . It also refers back to the ‘Pear Garden’ in that it also means to ‘pick’ or ‘take down’, as in picking fruit.

兒男 ér nán: a term that can mean either a male possessed of macho power, or a young boy. The poet returns to this term, by inverting it as 男兒 nán ér in the last line of the poem where it conveys a pointed meaning (see the relevant note below). We previously also noted in Ai Xiaoming’s poem that Geng Xiaonan is someone who ‘hardy yang in yin embodied’ 雌雄同體. See Ai Xiaoming 艾曉明, ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Dance of Defiance’, China Heritage, 16 September 2020.

This couplet embraces Geng Xiaonan’s name: it starts with her surname 耿 gěng; the second line starts with the first part of her personal name 瀟 xiāo and it ends with the second part of her personal name 男 nán. The poet returns to this acrostic device in the last three lines of the poem.

家國有事,豈可旁觀

塵埃一粒,其重如山

With the nation beleaguered thus, how could she stand idly by?

Every mote of trouble pressed down on her, weighty as a mountain

家國有事: a reference to the Gengzi Year of 2020. As Geng herself remarked:

Geng Xiaonan: The year 2020 is indeed a crucial time and, although I’m only a minor figure in all of it, I too feel the need to answer the question: What have you contributed? So,I will do whatever I can to offer you my assistance and support. I’ll also undertake whatever ‘homework’ you might assign me. I’m not just talking about Professor Xu Zhangrun. Because of the work I have done over the years organising and participating in various discussion groups, symposiums and seminars, I’ve been in frequent contact with a range of China’s independent public intellectuals, as well as significant artist-activists. They included not only prominent champions of Chinese law and legal reform like the rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang and Professor He Weifang [of Peking University], but also many other engaged public intellectuals, both in Beijing and Shanghai. I am happy to help in any way I can regarding contacts and organising things at my end.

As I’ve said, I am particularly aware of the importance of the critical year, 2020, although my more active involvement in things actually dates from 2018 [when Xi Jinping became effectively China’s ‘ruler for life’, resulting in a widespread sense of a looming political crisis]. Moreover, the roots of my hopes for these crucial few years were sparked over ten years ago. It was then [around the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games], that I was more focussed in thinking and working for China in the belief that we would see some significant changes within the decade, by 2018. I thought, surely by then enough will have happened [socially, economically, politically and culturally] for the county to be ready [for significant progressive political change]. China would be on the cusp. It was inevitable. But the years passed and things simply dragged on. I have no idea how long the Chinese people are fated to go on like this. Regardless, that’s why, Dear Ms Bei Ming, I am well equipped to respond readily to any ‘homework’ that you might chose to assign. I’ll undertake it to the very best of my abilities.

— from ‘The Kafkaesque Trials of Geng Xiaonan’

塵埃一粒, 其重如山 chén’āi yī lì, qí zhòng rú shān: from the line 時代的一粒灰,落在個人頭上,都是一座山, or ‘When only a single ash in an age of conflagration alights on the head of a single person it feels as though the whole weight of a mountain is bearing down on them.’ This is a line from Fang Fang, the pen name of Wang Fang, a well-known writer based in Wuhan, Hubei province, the epicentre of the outbreak of the coronavirus. See: 方方, ‘時代的一粒灰,落在個人頭上,就是一座山’, 10 February 2020. On 14 February, inspired by Fang Fang, a writer published the following poem online:

七絕 寄哀思

蒼天啊,還有多少塵埃尚未落下?

可有神功冠毒掃,江城重現艷陽天!

有彼君子,不懼危安

直言捅天,俠肝義膽

And that gentlemen, too, undaunted by any fear for his weal or woe

Unleashed his pointed works shaking the very heavens; valor true, cause righteous

彼君子 bǐ jūnzǐ: ‘there is that particular man of distinction’, in other words, Xu Zhangrun. For more on the word 君子 jūnzǐ, and the ‘jūnzǐ ideal’ in the context of Xu Zhangrun, see Feng Chongyi 馮崇義, ‘A Scholar’s Virtus & the Hubris of the Dragon’, China Heritage, 22 May 2019. The 彼君子 bǐ jūnzǐ used that opens this stanza is contrasted with 又有俠女 yòu yǒu xiá nǚ, literally, ‘then there is that woman warrior’, that is, Geng Xiaonan, the first words of the first line of the following stanza.

直言 zhí yán: a reference to Xu Zhangrun’s pointed polemical essays, which he started publishing in early 2016. The most famous of these is his July 2018 Jeremiad. ‘Imminent Fears, Immediate Hopes’ 我們當下的恐懼與期待. They are collected in《戊戌六章》 China’s Ongoing Crisis: Six Chapters from the Wuxu Year of the Dog (New York: Boden Books 博登書屋, June 2020). See ‘Six Chapters — One Hundred and Twenty Years’, China Heritage, 1 January 2020.

捅天 tǒng tiān: unsettle or strike out at Heaven. Here one recalls Geng Xiaonan’s evaluation of Xu Zhangrun’s post-January 2016 essays:

Blows directed at their Achilles Heel;

A sword pointed at the very Heart of Power. 直擊七寸, 劍指廟堂。

俠義 xiá yì: chivalry, to act on the basis of principle and a code of conduct, conveying a sense of righteous support for society at large no matter what the cost personally. It also conveys a sense of courage and rugged independence. Here the term 俠義 xiá yì is intermixed with 肝膽 gān dǎn, literally ‘liver and pancreas’, indicating someone who is brave and true to their beliefs on a visceral level. 俠 xiá, valiant spirit; independent, honourable and gallant person; a free agent. Traditionally, a knight-errant, as in 游俠 yóu xiá, was a ‘wandering knight’ or ‘freelance fighter’. The personalities and activities of 俠 xiá are the mainstay of martial arts, or Kungfu, literature and cinema.

又有俠女,牽馬扶鞍

亦步亦趨,挺身擋彈

Supported by this woman warrior, she leading steeds and offering comfort

Following closely in his wake, using her body to shield against outrageous fortune

俠女 xiá nǚ: As we noted in ‘The Kafkaesque Trials of Geng Xiaonan’, Bao Tong (鮑彤, 1932-), the most prominent and long lived persecuted liberal Party bureaucrat in China, used an oblique reference to celebrate Geng’s ‘chivalrous spirit’. In a piece of calligraphy presented to the publisher, Bao wrote that, in Geng Xiaonan, ‘The heroic spirit of Mirror Lake lives on’, 鑒湖英氣在, a reference to Qiu Jin (秋瑾, 1875-1907), the famous activist and revolutionary martyr who called herself ‘The Woman Warrior of Mirror Lake’ 鑒湖女俠. Qiu was executed in 1907 for her involvement in a planned uprising against the Qing government.

牽馬扶鞍 qiān mǎ fú ān: ‘lead a horse and hold the saddle [for the rider to mount]’. This a reference to Geng’s comment on the role that she saw herself playing as a supporter of China’s embattled independent thinkers:

‘If I could not be a hero, at least I could offer garlands to the heroic few and cheer on their endeavours. I could help them on their way or perhaps even take a bullet for them. Or, then again, I might serve by helping retrieve their fallen bodies from the battlefield… …’

我做不了英雄,但可以為英雄獻花和歡呼,為英雄牽馬,為英雄擋槍子兒,為英雄收屍……十二月黨人的女人已經深深烙刻進了我的骨髓,她們在青史上閃耀著獵獵英姿。

— ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Insights into the World of Xu Zhangrun (Part II)’

亦步亦趨 yì bù yì qū: to keep pace, to shadow someone, or to follow someone every step of the way. This fixed expression usually has a negative connotation, but not here.

挺身 tǐng shēn: literally ‘stand erect’, or ‘stand up straight [and with purpose]’, an abbreviation of the set expression 挺身而出 tǐng shēn ér chū, to straighten one’s back and take heroic action.

擋彈 dǎng dàn: ‘to take a bullet (for someone)’.

眾聲消歇,怒不敢言

川女血性,焉做寒蟬

The clamorous have suddenly fallen silent, swallowing their anger

Confronted by this spirited Sichuan Lady, how can they flinch in winter’s cold

眾聲消歇 zhòng shēng xiāo xiē: the question of sound, voice, speech and 噤聲 jìn shēng and ‘keep quiet’ or ‘fall silent’ 失聲 shī shēng in the face of tyranny and oppression.

怒不敢言 nù bù gǎn yán: ‘choked with silent fury’, 敢怒而不敢言 gǎn nù ér bù gǎn yán. As we noted in ‘The Heart of The One Grows Ever More Arrogant and Proud’ (China Heritage, 10 March 2020), a chapter in ‘Virtual Alarm’ devoted to Chen Qiushi 陳秋實, the lawyer and citizen-journalist supported by Geng Xiaonan detained for his online reports from Wuhan in February:

‘Du Mu’s famous poetic line “The folk of All Under Heaven/ Cannot voice their rage” 天下之人, 不敢言而敢怒 was reformulated as 敢怒而不敢言 gǎn nù ér bù gǎn yán, that is, ‘to choke with silent fury’. These words have given voice to popular outrage protesting autocratic behaviour, corruption and misrule for centuries. It is an expression that has resonated throughout the history of the People’s Republic of China. While it is all too common for people to ‘keep quiet’ 失聲 shī shēng in the face of repression, there are always those who ‘dare to speak out’ 敢言 gǎn yán.

For Du Mu’s poem — 《阿房宮賦》 — quoted both by dissidents and by Xi Jinping himself, see ‘The Great Palace of Ch’in — a Rhapsody’ and Ai Xiaoming’s poem of support for Geng which contains the line: ‘Witness, too, the impotent muted anger/ Vainglorious men averting their gaze’ 敢怒者無言以對/ 男子漢多是垂目低眉, a reference to those otherwise voluble men — many of whom have enjoyed Geng’s generosity in the past — though outraged by her arrest proved to be reluctant to protest or speak out on her behalf.’

川女 chuān nǚ: ‘a woman from Sichuan’. Geng Xiaonan is originally from Chongqing in Sichuan province.

血性 xuè xìng: paired with 俠女 xiá nǚ, courageous, gutsy, upright and loyal, to form the compound ‘formidable woman’. The expression is commonly used in 血性漢子 xuè xìng hànzi, that is, a man who is a solid friend and tough, although the English expression ‘red-blooded male’ hints at the darker aspect of the term. These terms, like 俠 xiá are heavily gendered due to the abiding chauvanistic nature of social practice and linguistic tradition. During the High Maoist era, some traditional terms were reinterpreted and applied across the gender divide, but long years of market-obsessed reforms have reinforced both old stereotypes and new commodified identities.

寒蟬 hán chán: ‘winter cicada’, that is a cicada, though raucous in the summer months, falls silent in the winter. One of its earliest occurrences is in the line: ‘Knowing what the good is but not advancing it; to hear of evil things but remain silent, hiding ones feelings to protect oneself, acting just like a cicada in winter’ 知善不薦, 聞惡無言, 隱情惜己, 自同寒蟬。See ‘Biography of Du Mi’ in History of the Latter Han Dynasty《後漢書·杜密傳》。

歲月靜好,不過裝酣

心系蒼生,一往無前

Your pretend security and heedless comfort is but a counterfeit pose

Those ones devoted to vast humanity’s cause continue on, determined

歲月靜好 suì yuè jìng hăo: from 歲月靜好, 現世安穩, ‘pleasantly while away one’s time and enjoying unperturbed peace in the now’. It also appears in the expression 時光未央, 歲月靜好: The good times keep rolling, so enjoy an untroubled life.

裝酣 zhuāng hān: ‘pretend to be satisfyingly drunk’, although it is also a homonym for 裝憨 zhuāng hān, ‘make a presence of stupidity’, that is to avoid trouble by putting on a show of ignorance or by pretending to be unaware of one’s environment.

蒼生 cāng shēng: literally ‘the growing grasses’, originally referring to the idea that the imperial ruler held sway over all life, including the most miserable tufts of grass. By extension it came to mean the common people as a whole.

一往無前 yī wǎng wú qián: to continue onwards without giving any thought to possible problems or obstacles. One of the obsessions of Chinese history and politics for over a century — advancing, moving forward, progress, a future-oriented approach as opposed to a backward looking restoration. The Xi era is one of reversals or an advance through reaffirming the past.

為眾抱薪,今遭風雪

嗟爾士子,嚅嚅囁囁

You enjoyed her generous support, but now she is battered by the tempest

Yet you, Fine Gentlemen — you hold back in obnoxious cowardice

為眾抱薪 wèi zhòng bào xīn: ‘to carry [provide] firewood for everyone else’, a reference to an epigram by the writer Murong Xuecun 慕容雪村 in May 2014:

‘We cannot let someone who has given us firewood freeze to death in the bitter winter cold. We cannot let someone who has forged a path of freedom be snared by a thicket of thorns.’

為眾人抱薪著者, 不可使其凍斃於風雪。

為自由開路者, 不可使其困頓於荊棘。

Murong’s line was quoted frequently during the mass online protests that broke out following the death of Dr Li Wenliang in February 2020.

嗟爾士子 jiē ěr shì zǐ, from ‘嗟爾君子, 無恒安息’ in the classic Book of Songs. ‘嗟爾君子, 無恆安息。靖共爾位, 好是正直。神之聽之, 介爾景福’, translated by James Legge as: ‘My honored friends, O do not deem/ Repose that seems secure from ill/ Will lasting prove./ Your duties quietly fulfill./ And hold the upright in esteem,/ With earnest love./ So shall the spirits hear your prayer,/ And on you happiness confer,/ Your hopes above.’ 士子 shì zǐ refers to those with prominent positions or social standing. Here it is used as a negative kind of 士 shì.

嚅嚅囁囁 niè niè rú rú: instead of simply being quiet they ‘don’t dare speak clearly’, simply prevaricate and mumble nonsense.

便車常搭,汝心可安

君子落難,圍觀聲援

You long enjoyed the free ride, can you really live with yourselves now?

Those outstanding are in trouble, gather round and raise your voices

便車常搭 > 搭便車 dā biàn chē: ‘hitch-hiker, free-loader, free-rider’. This is a dig at those who enjoy benefits without any thought for what it might cost. Also known as 酒肉朋友 jiǔ ròu péng yǒu, literally friends who only hang around to take advantage of free booze and food meals. In this case the expression means ‘fair-weather friends’.

君子 jūnzǐ: see the note on jūnzǐ in the third stanza.

撐我雨傘,遮君風寒

耿耿星河,曙光在前

I will hold high my umbrella, may it shield her against the bitter gales

Hers is shining example amidst a multitude of stars revealing the dawn ahead

撐我雨傘 chēng wǒ yǔ sǎn: ‘I open my umbrella’, ‘use my umbrella to support’. Readers would immediately associate the verb 撐 chēng and the noun 雨傘 yǔ sǎn with the 2014 Umbrella Movement in Hong Kong and the resistance in 2019-2020. See the background to the protest song ‘撐起雨傘’.

耿耿 gěng gěng: there the repeated term 耿 gěng alludes to being suffused with meaning, profoundly concerned with, strictly adhering to or to be faithful. This term also occurs in the set expression 耿耿於懷 gěng gěng yú huái, to be deeply concerned with, unsettled or perturbed.

曙光 shǔ guāng: ‘morning light’, a metaphor with strong resonances related to, but here opposed to, Communist Party rhetoric about a better future. The Milky Way is bristling with intense meaning and ahead lies the dawn light of possibility.

瀟瀟秋雨,漫漫長夜

男兒奮起,齊討兇頑

The autumn rains are relentless and a long night lies ahead

But those possessed of macho valor must surely stir

And together challenge those obdurate dementors

瀟瀟 xiāo xiāo: another meaning of 瀟 xiāo, as in 風雨瀟瀟, 雞鳴膠膠 ‘the wind whistles and the rain patters, far travels the cock’s crow’ (that translation after James Legge), which occurs in ‘Wind and Rains’, a poem in ‘Odes of the State of Zheng’ in the classic Book of Poetry《詩經·鄭風·風雨》。

秋雨 qiū yǔ: This recalls a famous line in the poem that Qiu Jin wrote shortly before she was executed in 1907: 秋風秋雨愁煞人 ‘Autumnal winds and rain — such sorrowful companions’

漫漫長夜 màn màn cháng yè: inversion of 長夜漫漫 cháng yè màn màn, ‘the long dark night’, which features in the ‘Ox-feeding Song’ 飯牛歌: ‘I have not been born at a time of wise rulers, and I am but a simple person in plain short clothes. Tending to my ox as the evening passes, ahead the long dark night stretches out. When will it ever be dawn?’ 生不逢堯與舜禪,短布單衣才至骭,從昏飯牛薄夜半,長夜漫漫何時旦。See 《淮南子·甯戚 〈飯牛歌〉》。

男兒 nán ér: here the poet recalls the first stanza of the poem, which featured the expression 兒男 ér nán. Here, however, he offers a somewhat different interpretation of the term, and hints at a well-known story. During his first Tour of the South in December 2012, the just-appointed Secretary General of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping is said to have referred to the reasons behind the collapse of the Soviet Union. In so doing, he supposedly quoted a famous line of poetry: ‘No real man among their number’ 更無一個是男兒. The line comes from a verse attributed to Madam Flower Bud 花蕊夫人, a concubine of Meng Chang 後主孟昶, the last ruler of the kingdom of Later Shu 後蜀, written as she witnessed dynastic oblivion:

君王城上竪降旗,

妾在深宮哪得知;

十四萬人齊解甲,

更無一個是男兒。

Flags of surrender on the ramparts

Deep in the palace how can I know:

140,000 lay down their arms,

No real man among their number.

In effect, Xi was saying that now China had just such a ‘real man’ 男兒 nán ér: that is, himself.

— from ‘The Real Man of the Year of the Dog 戊戌男兒‘

China Heritage, 2 March 2018

In this poem, however, the poet is exhorting the true 男兒 nán ér – that is the valiant women and men of China — to rise up to oppose The One, a man bloated with self regard.

奮起 fèn qǐ: to rise up forcefully or in a determined manner, to be roused into action to fight.

討 tǎo: ‘to attack’ here it has a double meaning of ‘to speak up and denounce’ 聲討 while hinting at the idea of ‘collectively mounting a campaign against the unrighteous’ 討伐。

兇頑 xiōng wán: an abbreviation of 兇暴愚頑 xiōng bào yù wán, a ‘vicious, wrong-headed and recalcitrant’ (person or group). Previously, we translated 邪魅 xié mèi as ‘abhuman dementor’. (See the concluding paragraph of Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘A Letter to the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University’, China Heritage, 19 August 2020.) Here we retain the word ‘dementor’, a neologism coined by the novelist J.K. Rowling, and preface it with the adjective ‘obdurate’, for (愚)頑 (yù) wán.

***

This last couplet contains an acrostic, the first line starting with 瀟 xiāo and the second with 男 nán, thus forming Geng’s personal name ‘Xiaonan’. This links with the previous line, which begins with the word 耿 gěng, which is Geng Xiaonan’s surname. By taking the first character in each of the last five lines of the poem we get the sentence:

君撐耿瀟男

You (君, or ‘people of any decency’ should) support Geng Xiaonan

***