Translatio Imperii Sinici &

a Lesson in New Sinology

‘The Revenant Han Fei’ is Part III of ‘China’s Heart of Darkness’, Jianying Zha’s coruscating reflections on the legacy of the ancient thinker Han Fei and the Legalist school in Xi Jinping’s China. It follows on from ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, ‘The Dark Prince’ and ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’.

***

‘China’s Heart of Darkness’ is presented here as a ‘Lesson in New Sinology’, one of a series focussed on the kinds of ‘literary-historical-intellectual’ 文史哲 usage and allusions that are a central feature of contemporary Chinese politics and culture. It is also a chapter in Translatio Imperii Sinici, a series which is concerned with the ideas, habits, cultural expressions and aspirations of empire that have marked China’s modern history, and which continue to influence the Chinese world in a myriad of ways.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

20 July 2020

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Part III: The Revenant Han Fei

Jianying Zha

查建英

Keeping Pace With the Times!

In retrospect, it’s more than evident that Xi’s early pledges to ‘rule by law and the constitution’ were little better than doublespeak, although I’d note that it was easy enough to think of 法治 fǎ zhì as ‘the rule of law’, where in fact it really means ‘rule by law [as determined and administered by the Communist Party]’. All the lofty and obfuscating utterances basked in the sun of public approval were masking relentless and clandestine action that crept around in the dark. In fact, as we have noted in the above, these are actually two sides of the same coin; this is 勢 shì and 術 shù in operation.

Mao Zedong was an undeniable master of the ancient art of treachery — the thrust and parry of struggle, the feints of political pugilism, the deflections of discourse. Operating with ruthless opportunism, he ‘flashed, flipped and flopped’ his words with breathtaking aplomb; his unpredictability and volatile political shifts often left his enemies (as well as many of his devoted followers) completely disoriented. For Mao politics was a blood sport, a forever war; only a simpleton would think it necessary to honour a promise on principle or play by the rules when it was in his interest to indulge his talent to ‘bait-and-switch’.

At this juncture, it is interesting to recall that Mao expressed particular disdain for a noble if hide-bound king in the pre-Qin era. Duke Xiang of the Kingdom of Song 宋襄公 was defeated by an unprincipled enemy because he conducted war according to what proved to be an outmoded code of honour. As Mao remarked in ‘On Protracted War’, a famous series of lectures delivered in 1938:

‘We’re not Duke Xiang and we have no use for such asinine ethical considerations.’

我們不是宋襄公,不要那種蠢豬式的仁義道德。

Mao’s unsentimental utilitarianism was deeply rooted in ideas related to 勢 shì and 術 shù discussed above, in which military tactics, statecraft, diplomacy, as well as commerce and trade, are seen as being interconnected and complementary domains. All human activities are included in an amoral calculus of needs, wants and proclivities. To skillfully manoeuvre and leverage such forces to one’s advantage is a high art, and in the pursuit of strategic goals anything and everything can come into play.[13]

[Note 13] See Mao Zedong ‘On Protracted War’ 論持久戰, May 1938. Another example of the Party’s tactics had a momentous influence. During the Civil War of 1946 to 1949, the Communists repeatedly pledged that when in power they would fulfill the original promise of the Republican revolution of 1911-1912 by making China a modern democracy in which citizens would enjoy universal suffrage and guaranteed human rights in regard to freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and so on. As victory loomed Mao changed tack and announced the Party’s true ‘original intention’ as being the creation of a ‘people’s democratic dictatorship’. See Mao Zedong, ‘On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship’ 論人民民主專政, 30 June 1949. For details of this excruciating volte-face, see an anthology of the promises that the Communists betrayed compiled by Xiao Shu 笑蜀 (陳敏), Forgotten Voices of History: Solemn Promises Made Half a Century Ago 歷史的先聲: 半個世紀前的莊嚴承諾, Shantou: 1999.

The barefaced genius of 勢 shì and 術 shù is alive and well today; it is pursued assiduously both by specialists and by members of the interested public who have long been trained to think and act strategically. It is updated and rejigged to suit contemporary conditions, and it is pursued in every realm of life by those who believe that it offers a time-honoured, and historically tested, key to survival and success. The ‘flying dragon’ that first appeared in ‘Qian 乾’, the first hexagram in the I Ching, the ancient Book of Change used for millennia as a tool of prognostication — that same dragon mentioned in the quotation from Hanfeizi above, having vaulted into the sky still beats its wings as it navigates a path forward through light and shadows, its sinuous body constantly buoyed and roiling in the currents of air, always partially obscured by the clouds. This dragon never fully reveals its form — and its occluded promise and threat inspire awe, as well as dread. Down the ages strategists have known: words are one thing, what really counts is action. To play a long game successfully requires patience and artifice; ofttimes the canny protagonist is smart enough to play dumb. It is perhaps misguided to think of Xi Jinping as a reckless strongman; this is a crude exaggeration. Similarly, his bureaucratic rivals and systemic opponents have learned at their peril: it is unwise to underestimate either his intelligence or his cunning. People have made that mistake for far too long.

As he patiently climbed the career ladder over the decades, Xi cultivated the bland image of a competent official possessed of an unassuming and respectful manner; in particular, he was noteworthy for a solid if lacklustre record of achievement. He patiently ingratiated himself with Party elders and was eventually selected by the chosen few as a successor to the ultimate position. Then and only then did he reveal himself. By then it was too late and once he had assumed the mantle of party-state-army leader in early 2013 he proved that when required he could be as bold as he was stealthy. His public utterances were forceful and brimming with righteous purpose; although if necessary his loquaciousness could be confoundingly ambiguous.

Over the past eight years, Xi Jinping has given China and the world something of a masterclass in the ‘propensity of power’ 勢 shì showing just how the audacity of Han Fei can play out in contemporary politics. And he knew just how to maximise its potential. Advancing with guile and gumption, Xi has proven that he has long prepared for this moment. Power politics is his home turf. As for some of his apparently heavy-handed overplays and miscalculated moves in the geopolitical arena, just exactly how severe their adverse consequences will prove to be remains an open question.

Going Low from the High Ground

‘Ensure that power operates in the sun.’

‘No organisation or individual is above The Law and the Constitution.’

By deploying such modern and reformist dicta, Xi sought the moral high ground for himself as part of his signature anti-corruption campaign. Such high-minded vagueries encouraged wishful thinking and self-delusion among those who were hopeful that under his rule China would finally see substantive new economic and political reforms. Ears delighted by such dulcet tones, heads clogged by the fog of verbiage, these people were easily, even willingly, misled. At that point — from 2013 until relatively recently — how many people were willing to pause or deign to focus on a few dusty and oblique lines that the new ‘Chairman of Everything’ chose to quote from some two-thousand-year-old pre-Qin Legalist classic?

But the signposts were there, albeit in a language that few were equipped to decode. As we argue here: the key to understanding what Xi really means by ‘rule of law’ lies in Hanfeizi and the Chinese Legalist tradition. So let’s recall that line Xi quoted from Han Fei in the context of what followed:

‘No country is permanently strong, nor is any country permanently weak. If those who impose The Law 法 fǎ are strong, the country will be strong; if they are weak, the country will be weak.’

國無常强,無常弱。奉法者强則國强,奉法者弱則國弱。—《韓非子 · 有度 》

Who are those who ‘impose The Law’ here, and what Law, exactly, is being enforced? Who controls the legislature that frames and approves The Law, and what precisely does the word ‘permanent’ really mean now? As Chairman Mao knew all too well: it is all about power. Although Xi prefers a more modern and ostensibly reasonable formulation: ‘constrain power within the cage of the governance system’. Today, as in the past, the crucial thing is not the cage itself — that’s a given — or, indeed, who ends up being caged. What really counts is who holds the key to the cage? Remember the leash around the dog’s neck? As an observation current among Chinese economists puts it: in the West the invisible hand is that of the market; in China the hand belongs to the state. When the controlling hand is that of a strong leader and the law is his to manipulate, well, as Han Fei warned long ago: nothing is permanent. Keep pace with the times!

The Revenant Han Fei

The spectre of authoritarianism is casting a long shadow. It’s identified in various ways, popular terms for it include Yascha Mounk’s ‘illiberal democracy’ and John Keane’s ‘new despotism’ (although this term was first used as a title of a book on British politics in 1929). The spectre has taken shape as all that seemed normal has melted into air. Zygmunt Bauman famously described ‘liquid modernity’ and in recent years the dubious concept of Zeitgeist seems to be enjoying a new lease on life.

In China, however, there is nothing particularly new about despotism. Moreover, every despot in that country’s history, from Qin Shihuang to Mao Zedong, has taken a shine to Prince Han. His return to the political arena in the twenty-first century under the aegis of Xi Jinping is no accident, and it certainly doesn’t bode well for the enemies of the state, be they on Mainland China, in Hong Kong or, for that matter, in Taiwan.

The second Hanfeizi quote in Xi Jinping’s Top Ten Favourites reads as follows:

‘As to the subordinates employed by an All-seeing Sovereign, the chancellor must have risen from the ranks of district-magistrates and brave generals must have emerged from among the common legions of soldiers.’

故明主之吏,宰相必起於州部,猛將必發於卒伍。—《韓非子 · 顯學》

Xi has quoted this line no fewer than five times, though out of faux modesty he omits the first part of the sentence related to ‘the intelligent sovereign’ 明主 míng zhǔ, and talk of ‘subordinates’ 吏 lì would smack of un-comradely elitism.[14] But the core message remains: officials should be evaluated and promoted on the basis of grass-roots practical experience rather than according to their previous rank or theoretical knowledge. This would appear to be sage advice and it conforms with Xi’s own trajectory: his formal education was cut short and his official career, one could argue, kicked off with a modest county-level position.[15] Thus, it is hardly surprising that he embraces this hoary dictum from Hanfeizi. Yet Han Fei’s counsel conveys a more cunning message: promoting practical-minded, soldier-like officials obedient to orders from above will limit the power and prestige of Confucians, the existing nobility and entrenched groups — those smug, morality-spewing lobbyists with a mind of their own and independent values should never be trusted. Han Fei knew exactly what type of men would be better suited to serving the supreme ruler.

[Note 14] Such telling omissions are a common feature of the way Xi selectively quotes classic wisdom. For example he has repeatedly employed a truncated line from Xunzi:

‘When policies keep pace with the times, the people unite as one and the virtuous comply.’

政令時,則百姓一,賢良服。

Tellingly, Xi always omits the extended first part of this quotation which is taken from Xunzi’s admonition in ‘The Rule of the King’ 王制 which advises the ruler to treat his subjects with benevolence and equality:

君者,善群也。群道當,則萬物皆得其宜,六畜皆得其長,群生皆得其命。故養長時,則六畜育;殺生時,則草木殖;政令時,則百姓一,賢良服。—《荀子 · 王制》

[Note 15] This claim, regularly made in official propaganda about Xi, is actually tendentious. Xi’s first official post was as a secretary for Geng Biao 耿飈, an old subordinate of Xi Zhongxun, Xi’s father, and a man who was by then vice-premier, minister of defence and secretary-general of the Central Military Commission of the PLA. Xi’s inexorable rise through the ranks was unquestionably related to his status as a ‘Princeling’, or member of the Party gentry.

So does Xi Jinping. The best servants of the state that Xi envisages are those who are unquestioningly loyal. Locally bred men and women who are thoroughly rooted in their indigenous experience are less likely to be swayed by fancy ‘big city’ notions or corrupting foreign values. Promotions thus focus on this cadre so as to ensure fealty to the great leader. As a result the individual’s social status, as well as their prospects for material gain, can effectively be aligned with the agenda of the state and its ultimate embodiment: the leader. Since 2012, Xi Jinping has promoted Party officials, military generals and bureaucrats along precisely these lines. After the hard-won professionalisation of the system and the rise of competent technocrats over the preceding decades, now loyalty often counts more than talent and education.

In a recent exchange with a Shanghai-based veteran observer of party-state politics who has been tracking and analysing official promotion patterns under Xi, I remarked on the precipitous rise to prominence of men who had for the most part previously served under Xi during his years as a provincial administrator, individuals who shared his grounding in Marxism-Leninism and the study of Party-ordained political thought. ‘Sure, but it goes further than that,’ my interlocutor smiled:

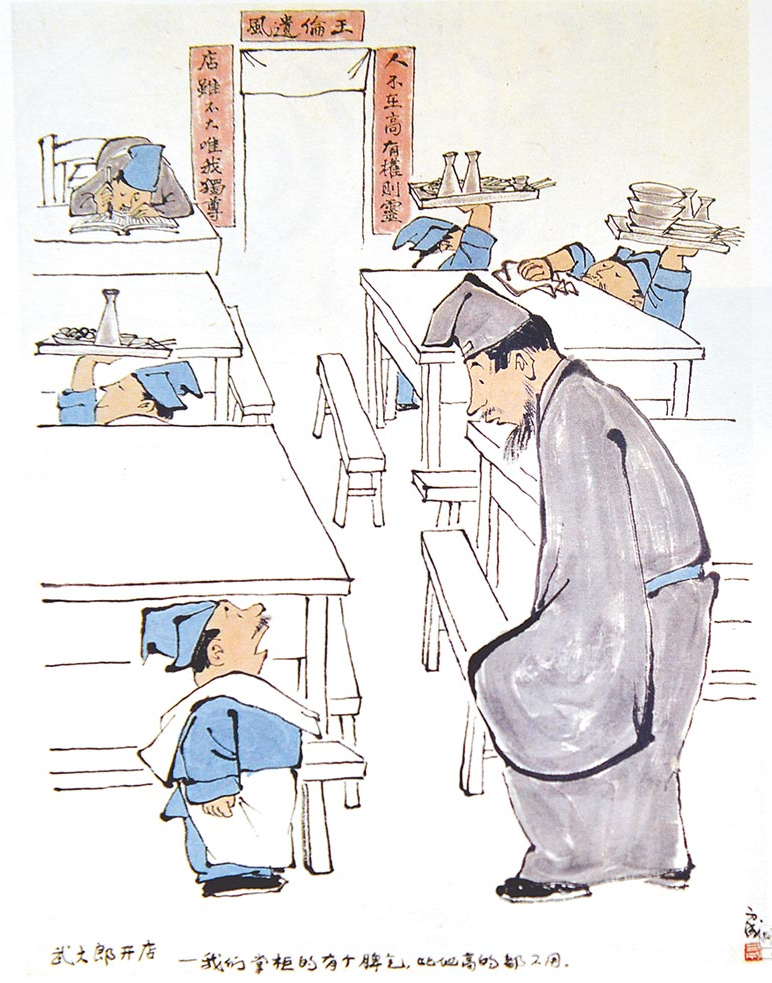

‘In a lineup of, say, six or seven candidates ranked according to ability, Xi has routinely endorsed not the first or the second in the running; rather he’s opted for the sixth or even the seventh. The successful candidate is achingly aware that they’ve been promoted over the heads of more qualified people so, as a result, they are obsequiously grateful and feel absolutely duty-bound to Xi personally. In the past, Party leaders like premier Zhou Enlai had pursued a policy of “turning the talented into the servant” 把人才變成奴才; today, Xi Jinping’s approach is rather that ‘being a servant makes you a talent’ 奴才就是人才. This, added to the reactivation of Party committees and cells at every level of government and business makes the mechanism of control and command particularly effective.’

But, surely this begs the question: effective for what?

***

***

Another Great Teacher

A question of the utmost importance for Han Fei is the manner in which rulers deal with something known by the shorthand expression 賞罰 shǎng fá — rewards and punishments. In Hanfeizi they are known as the ‘Two Handles’ 二柄 èr bǐng, a grip on which is crucial to establish and maintain control. The interconnected rods are, in fact, somewhat akin to the caduceus, the wand in which two intertwined serpents symbolise balance. Similarly, a ruler is assured of success if they know how to apply policies of reward, or promotion, and punishment, or demotion, judiciously. The mismanagement or delegation of powers crucial to firm rulership could, Han Fei warns, undermine the ruler’s authority over time and may well ultimately cost him his throne.[16]

[Note 16] 賞罰 shǎng fá, rewards and punishments, is a subject treated at length in other Legalist works, in particular in The Book of Lord Shang 商君書. There Shang Yang demonstrates yet again his trademark cruelty and mercilessness — ‘awards and promotions should be given out sparingly, thus people will strive after them; however, punishments and fines should be frequently apportioned and they must be severe so that people will be too scared to commit any misdemeanors or crimes.’ Han Fei’s approach is more refined, although he does combine meticulous calculation with hardheaded pragmatism. While it is noteworthy that Xi Jinping has chosen to quote Han Fei on the subject, elsewhere he also praises Shang Yang.

There is no doubt that Xi Jinping has established a firm grip on the Two Handles. But is he keeping them in balance?

As I have argued in the above, the work of Han Fei offers an insight into the evolution of China’s party-state, but there is more to Xi Jinping’s doctrine of governance than the tradition of brute Legalism, for just as the fulcrum of rewards and punishments is in the hands of the ruler, so too are the dual aspects of Law and Morality. This dyad also features prominently in Xi’s public statements and it is evolving not only in the context of modern Chinese government, but also within the hoary tradition of Dong Zhongshu of the Han dynasty when, as we will recall, the unsparing Legalist tradition of Shang Yang, Han Fei et al was married to the high-minded ideas of Confucius and Mencius. Again, as we have observed, a measure of quasi-spiritual abstraction from the Taoists was also thrown into the mix.

Time and again, Xi Jinping returns to the nexus between Law (or political power) and Morality (that is Party ordained social virtues). Here he is building on a post-Cultural Revolution doctrine originally articulated by Deng Xiaoping and then reformulated by Jiang Zemin, that holds that the Communist Party’s dominion over China is one that ‘adheres both to the Rule of Law and the Rule of Virtue’ 堅持法治與德治并舉. As is the case in regards to other aspects of Party dogma, Xi Jinping is taking things much further than his predecessors and articulating them at great length. Let me give you a sample of his ex cathedra remarks:

‘Law is morality in written form while morality is the inner law of the heart-mind. Together they contribute to regulating social behavior and maintaining social order.’

法律是成文的道德,道德是內心的法律,兩者都具有規範社會行為、維護社會秩序的作用。

‘There are two ways to governing a country … the rule of law and dominion of virtue are complementary and indispensable. They are like the two wheels of a cart or the two wings of a bird. While law safeguards the realm, virtue nourishes the heart-mind.’

法治和德治作為兩種不同的治國方式 … 相輔相成、缺一不可,猶如車之兩輪、鳥之雙翼。法安天下,德潤人心。

‘The rule of law and the rule of virtue must be grasped with both hands, and our grip must be equally tight over both.’

法治和德治两手抓,两手都要硬。

Such sentiments are repeated ad nauseam in China’s official media.

For a student of Chinese history, talk about the indivisible nexus between Law and Morality is familiar for it has long been regarded as a central feature of China’s paternalistic style of ‘good governance’. Once the uprising, war and the overthrow of the existing order are done with, newly ensconced rulers would seek to replace ‘the chaotic age’ 亂世 luàn shì, of which they had taken advantage to advance their own cause, with an ‘era of order and stability’ 治世 zhì shì. They kept a steady eye on ushering in ‘a prosperous world’ 盛世 shèng shì, or at least they acquiesced when sycophantic courtiers hailed their reign as a new golden age. Hence for some two millennia rulers have repeatedly relied on a similar governing axiom, one which has been expounded on at length from ancient times, initially by pre-Qin thinkers like Guanzi and Xunzi, and then from the establishment of State Confucianism during the Han dynasty. Thereafter, the Confucian-Legalist mantra of Law-Morality has been something of a constant.

A related discourse regarding the two contrasting approaches to rule — by salient virtue and wisdom, 王道 wáng dào, literally, ‘The Kingly Way’, versus rule by force majeure, 霸道 bà dào, ‘The Path of Domination’ — also dates back to a pre-Qin debate between the Confucians and the Legalists. Confucius and Mencius were the principal advocates for 王道 wáng dào, while Han Fei and others argued in favour of 霸道 bà dào. The fence-straddling Xunzi suggested a third option: rule by melding force with virtue 霸王道雜用. A common view holds that rulers since the Han dynasty tended to adopt Xunzi’s form of amalgamation. Today people still readily refer to this pre-Qin debate when discussing hegemony, be it hard power versus soft power within China or in discussing the fortunes and strategies of nations on the international scene.

Xi is versed in these ideas. If we put his personal role, and individual quirks to one side, we should also appreciate his contribution to a long-term process of historical change within tradition. This is in part the subject of the series Translatio Imperii Sinicii produced by China Heritage to which the present essay is a contribution.

***

***

The Pole Star

Quoting The Analects Xi Jinping has also observed that: ‘He who rules by virtue is like the Pole Star. It is a fixed point in the firmament to which all lesser lights pay homage.’ (We should note that, in the Maoist heyday, the Great Helmsman was also referred to as the Pole Star/ Big Dipper 北斗星.)

The aspirations of the Chairman of Everything are not limited by his titular role as head of China’s party-state-army, for he also sees himself as the exemplar, mentor-guide and teacher of the entire nation. No leader since Mao has harboured such a grandiose pedagogical-transformative ambition and Chairman Xi has an opinion on and guidance for just about every issue and situation in life, politics, society, culture and what have you. His voluminous bloviations are published and repeated with dutiful reverence by the media and at mandatory study sessions and via online apps. While tedious party-speak remains the mainstay of his unfailingly ‘important directives’, references to the tradition and to dynastic-era classics also come thick and fast. As we have indicated in the above, the bibliography of his citations is something like a ‘Reader’s Digest Library of Chinese Knowledge’: there’s things from Confucians, Neo-Confucians, Legalists and Taoists, as well as lines from various Buddhist sutras, a phalanx of military strategists, as well as gleanings from scholar-bureaucrats and statesmen from various points in Chinese history. Freighted with a certain high-culture mystique and exuding an aura of intellectual authority, such terse and eloquent morsels are a garnish that embellishes Xi’s otherwise lacklustre speeches. As Mao said: ‘The past should serve the present’ and in Xi’s world the luminaries of all ages are press-ganged into service, lining up to sanctify the Xi Vision and Xi’s Mission; their borrowed authority consecrates Xi’s mandate.

Xi and the Party thinkers — the collective ‘imagineers’ of ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ — constantly draw on the tradition as they advance the adaptation of modernising Western ideas to Chinese reality. More broadly, it is a process that has been under way for over a century. One of the landmark moments in that history was the publication in 1939 of Liu Shaoqi’s On the Self-cultivation of Communist Party Members 論共產黨員的修養, also known as How to be a Good Communist. It is a work to which Xi Jinping has referred, but more importantly it is a tract that offered the first clear articulation of how indigenous Chinese ideas were being harnessed for the Communist cause.

In addressing a motley crew of zealots and discontents who had just completed the Long March, Liu used the power of the lectern, and his position in the Party hierarchy, to temper and mould his audience into a more disciplined, unified fighting force. In what remains a crucial text for appreciating Chinese Marxism, Liu’s Cultivated Communist lectures fused citations from The Analects on Confucius’s own lifelong journey of self-cultivation (and quest for political influence) with Mencius’s celebrated and stirring reflections on noble suffering and heroic sacrifice of the individual for the sake of a higher spiritual mission; a mission, we would hasten to add, that combined good governance with individual fulfillment. Liu’s might not have been the earliest attempt by a Party leader to appropriate elements of the Confucian tradition, but it remains to this day the locus classicus of all subsequent permutations of what is a crucially important ‘cultural turn’. In his lectures, and the subsequent pamphlet published on the basis of his talks, Liu aimed to curb various forms of unruly, selfish and individualistic tendencies then prevalent among the revolutionary cadre — men and women from diverse backgrounds who had inchoate, and often unrealistically idealistic, aspirations.

***

***

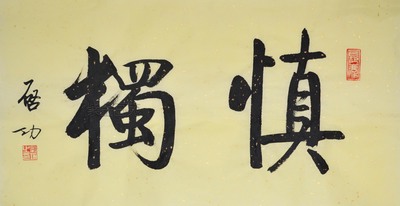

For his part some seventy years later, Xi Jinping singled out Liu Shaoqi’s advice to Party members that they should practice 慎獨 shèn dú, or ‘solitary contemplation’ (also known as ‘Confucian-style meditation’), that is, ‘the quiet contemplation of virtue and value pursued alone in a meditative state of mind’.[17] However, for Xi such lofty appeals to Party members are always articulated so as to strike a balance between the ‘Kingly’, or politically virtuous, with the ‘Hegemonic’, that is relentless domination. Thus, even when Xi appeals to the higher goals of Communist ideology time and again he will preface his remarks with talk about iron discipline and submission. That is why Han Fei repeatedly finds favour in service of yet another Chinese autocrat:

‘Those who pursue the personal will but invite chaos, while those who cleave to 法 fǎ “Law” will usher in orderly rule.’

道私者亂,道法者治。—《韓非子 · 詭使》[18]

Elsewhere Xi’s speeches are full of this age-old see-sawing between Confucian high purpose and uncompromising Legalist manipulation and control.

[Note 17] From Xi Jinping, ‘In Pursuit of the High Goal of “Solitary Contemplation” ’ 追求「慎獨」的高境界, New Words from the Zhi River《之江新語》, 25 March 2007.

[Note 18] From Xi Jinping, ‘A Speech on the Occasion of Drawing Lessons from the Party’s Campaign on the Practical Implementation of Mass Line Education’ 在黨的群眾路線教育實踐活動總結大會上的講話’, 8 October 2014.

End of Part III

***

China’s Heart of Darkness

Prince Han Fei & Chairman Xi Jinping

Jianying Zha 查建英

Contents

- Prologue: ‘Qin Shihuang + Marx’, 14 July 2020

- Part I: ‘The Dark Prince’, 16 July 2020

- Part II: ‘Mao’s Abiding Legacy’, 18 July 2020

- Part III: ‘The Revenant Han Fei’, 20 July 2020

- Part IV: ‘The End of the Beginning’ & ‘Chairman Xi Jinping’s New Clothes, an editorial postscript’, 22 July 2020