The writer and translator Linda Jaivin gave the opening speech at an exhibition of photographs of hutong 衚衕, the unique (and all-but-disappeared, or destroyed by restoration) alleys of Beijing, by the artist Xu Yong 徐勇 at the Vermilion Gallery in Sydney on the 4th of May 2017. Linda, a long-term collaborator and a frequent contributor to Heritage projects, has kindly given us permission to publish her remarks. Vermilion has provided images of Xu Yong’s haunting work.

As Linda notes on the day she gave her speech, May Fourth — the anniversary of student demonstrations in 1919 — was only a month away from the twenty-eighth anniversary of the crushing of another patriotic student-led uprising in the Chinese capital in 1989. To continue our commemoration of that event (see The Gate of Darkness), we reproduce below an essay by Zhang Langlang about one particular hutong next to Tiananmen Square, and the fate it suffered.

***

The hutong of Old Peking and the life they nurtured have been under threat and in decline for over a century. With the end of the imperial era and the collapse of the economy, social order and civilisation of Manchu-dominated Beijing, the vicissitudes of modern Chinese history have constantly buffeted the fabric of hutong life. In the 1940s, the influx of refugees and further economic deprivation created tenement hutong 大雜院. With the arrival of the Communists and their vision for a socialist city, a mass resettlement of non-Beijing workers led to further crowding and the displacement of the original residents, or at least their sidelining. Following more than a decade of urban stagnation, from the late 1970s official policy was to destroy all but a few ‘model hutong‘ and the rehousing of the dislodged inhabitants in high-rise buildings. Then came the tide of commercialisation in the 1990s and with it developers, speculators and phoney heritage conservation. All the while Beijing has been ruled over by outsiders who, at best, encourage the mummification of Old Peking culture for the sake of their own aggrandisement and profit.

***

Linda Jaivin is herself familiar with the remains of Beijing hutong life: when she visits and works in the city, which is frequently, she lives in a courtyard house near Zhonggu Lou 鐘鼓樓. The old city’s hutong were a feature of work in China Heritage Quarterly. In China Heritage we will return to this topic in the future.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

The Hutong Photographs of Xu Yong

Linda Jaivin

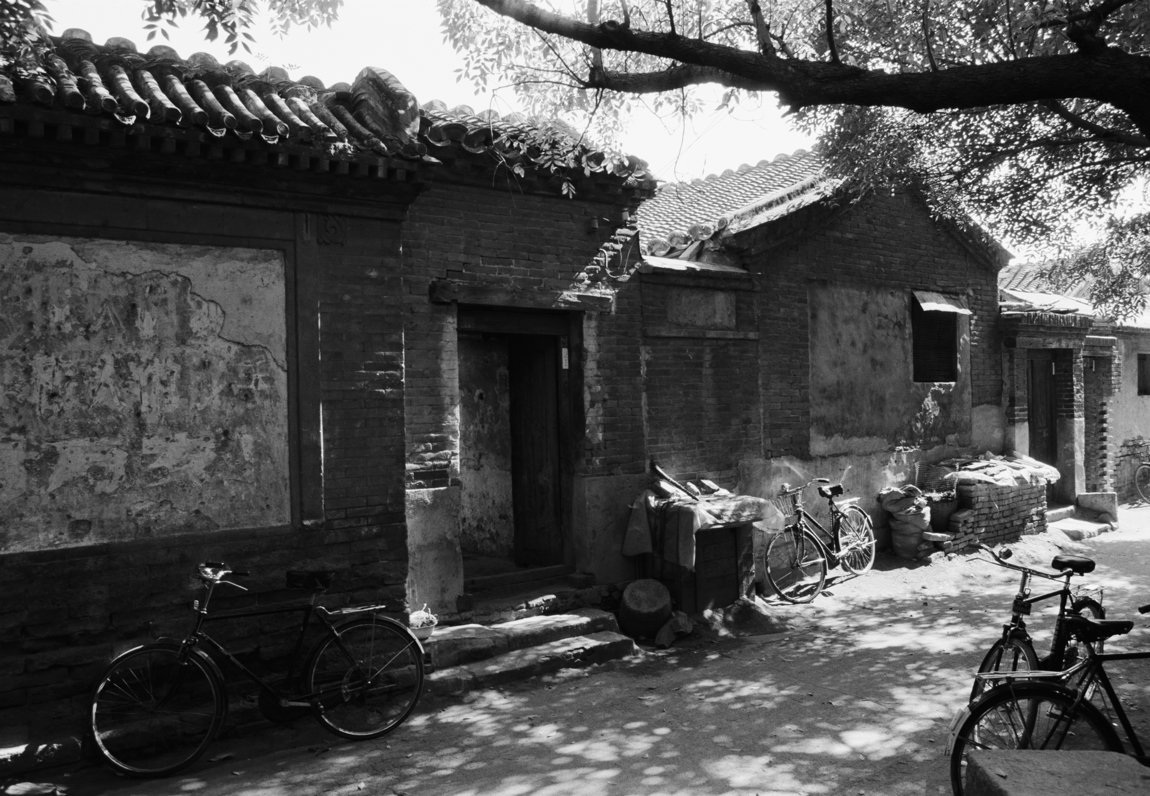

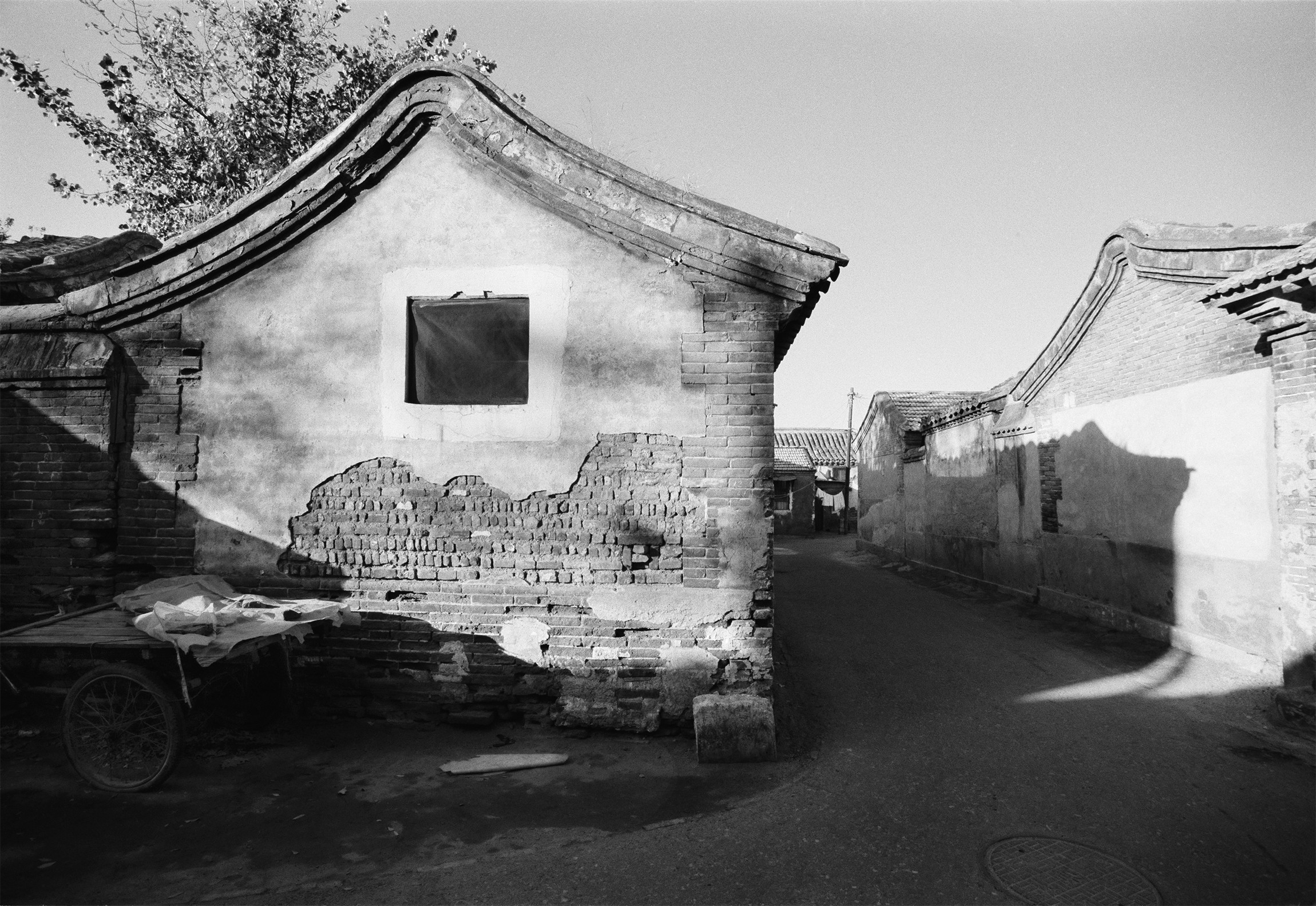

I’m delighted to have been asked to open this exhibition of Xu Yong’s photographs of Beijing hutong, the narrow, grey-walled alleys and lanes that are as much a part of the historical identity of China’s capital as the imperial palaces, temples and parks.

I’m going to speak to you about the history and character of the hutong, and tell you some stories about the people who have lived in the ones photographed here. But before we talk about these 700 year old alleyways, I want to acknowledge that we are standing on a land that has 60,000 years of history and culture — Aboriginal land. I wish to pay my respects to the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation and to their elders past and present.

***

The hutong are the connective tissue of the unique organism that is the traditional Beijing lifestyle, a mix of the ceremonial and the familial, the public and the private, the hidden and the communal.

On the one hand, the long grey walls of hutong hide people’s homes from view. On the other, they are a space where neighbours meet, children play, and gossip travels. There is a unique Beijing slang for bearer of news and gossip: hutong chuanzi 胡同串子. Chuanzi is the up-tempo percussion that accompanies an actor in Peking Opera who is racing around the stage in circles — a stylized action representing great distance.

Speaking of walking in circles, everyone who knows Beijing has had the disorienting experience of searching for a place you once knew well that has suddenly disappeared. The wrecking ball of greed and corruption and official indifference or collusion has collapsed countless hutong walls and homes into rubble. So many places, quirky, unique, are now simply the landing sites of anonymous towers of glass and steel.

Xu Yong made his hutong photographs almost three decades ago. Today hutong homes, especially intact courtyard houses, are much coveted. At the time, however, it has to said, locals had no romantic illusions about hutong life.

Homes once intended for a single extended family now housed many. Heating came from coalbrick-fired stoves. Electricity and water supplies were a bit of a crapshoot. Kitchens were makeshift lean-tos in the courtyard and the toilets were outside, public and foul. (They still are.)

But Xu Yong was from Shanghai and the hutong fascinated him; he saw beauty where residents saw slums.

***

The contemporary destruction of the hutong began, slowly at first, about four or five years after Xu Yong shot these photographs and about seven hundred years after the first ones were laid out.

Hutong first came into being in the thirteenth century as part of Khubilai Khan’s Khanbaliq. Cities had existed on this patch of China’s northern plains for more than two thousand years by the time Khubilai Khan’s urban planners laid out the chessboard grid of the city with its nine straight north-south and east-west avenues wide enough for nine chariots to travel side by side; minor streets half as wide, and finally, the hutong, twenty-nine in all. (Later, as Beijing grew, the hutong grew in number to over 1,200.)

From the thirteenth century to the present day, Beijing has been home to countless military and civilian officials — making it a bit like Canberra, I suppose.

In the Yuan, Ming and Qing there were strict rules about who could live where. Strict regulations prescribed the size of your home and even the exact depth of your doorway. You could tell, for example, if a highly ranked military official lived there: the entryway would be deep and there’d be stone wardrums on either side of the door. Today, you look for the grand entryways, of course, but also the CCTV cameras and the luxury cars with military license plates.

But a hutong is not a gated community, and anyone can enjoy its pleasures: Wild grasses grow from even the grandest of the sweeping ceramic tile roofs and spring breezes can share peach blossom petals from hidden gardens with the street.

Peddlers and itinerant craftsmen still work the hutong, although they are neither as numerous or as colourful as in the past. You hear them singing out their wares: quilts for winter, potted plants for spring, cold sour plum soup for summer and the fat grapes called tizi in autumn. They collect your old bottles and your old microwaves. Almanac peddlers once bounced piles of string-bound books on the ends of shoulder poles, today vendors of the Beijing Daily stack tabloids in the baskets of their bicycles, advertising them with a recorded squawk: 北京日報! 北京日報!

***

The names of hutong often tell you something of their history. Take Zhanzi Hutong 氈子衚衕, for example. A zhanzi is a felt rug. This hutong was once home to workshops that produced rugs and blankets to help insulate the palace and keep the emperor and his entourage warm in the harsh Beijing winter.

Nearby is Qianjing Hutong 前井衚衕, or ‘Front Well’ Alley, where an eighteenth-century Manchu general lived. He served the Qianlong Emperor well, and Qianlong married his ninth daughter to the general’s son. Their home on Qianjing Hutong became a 公主府, the official residence of a princess. By the Republican period, their descendants were still living there, but the family fortune was in decline and the home was divided and in disrepair. It was completely destroyed in the Cultural Revolution, and replaced with another building though I believe you can still find a small part of the old family temple there if you look hard enough.

Number 23 北溝沿衚衕 — North Ditch Hutong, meanwhile was for a time the home of Liang Qichao 梁啟超, a radical thinker who in 1898 was part of a group who persuaded the Guangxu Emperor to adopt a program of reform aimed at turning the Qing into a constitutional monarchy with modern government and education. One hundred days later, Guangxu’s powerful aunt put the emperor under house arrest, where he remained for the rest of his life. Liang escaped to Japan. Other reformers were executed on the site of what is now a Walmart, incidentally. Another One Hundred Days Reform Fun Fact: Liang visited Australia at the time of Federation, met Sir Edmund Barton and thought the Australian model of federation might work for China.

His son, Liang Sicheng 梁思成, became an architect devoted to the documentation and preservation of Old Peking. He advised the Communists to build their monumental buildings away from the Forbidden City, to leave the historic hutong neighbourhoods there intact. They didn’t. The memory of those neighbourhoods lies crushed beneath such structures as the Great Hall of the People. Distressed, persecuted and now dead, Liang Sicheng is one of the great heroes to China’s contemporary urban conservationists.

The last hutong I’ll talk about tonight is 豐盛衚衕. Fengsheng means ‘sumptuous’ or rich and is either a reference to the name of a Ming general or the wet nurse of a Ming emperor, no one knows for sure. Fengsheng Hutong is today best known as the home of one of twentieth-century China’s greatest and most beloved writers, Lao She 老舍, the author of such classics as Rickshaw Boy 駱駝祥子and Tea House 茶館. On 23 June 1966, Red Guards beat and abused Lao She, then sixty-seven years old, for hours alongside other Beijing artists and intellectuals. The following day his body was found in Taiping Lake (which like many hutong, no longer exists). You can visit his old home. The calendar on the desk remains open to the date of his death: 24 August 1966.

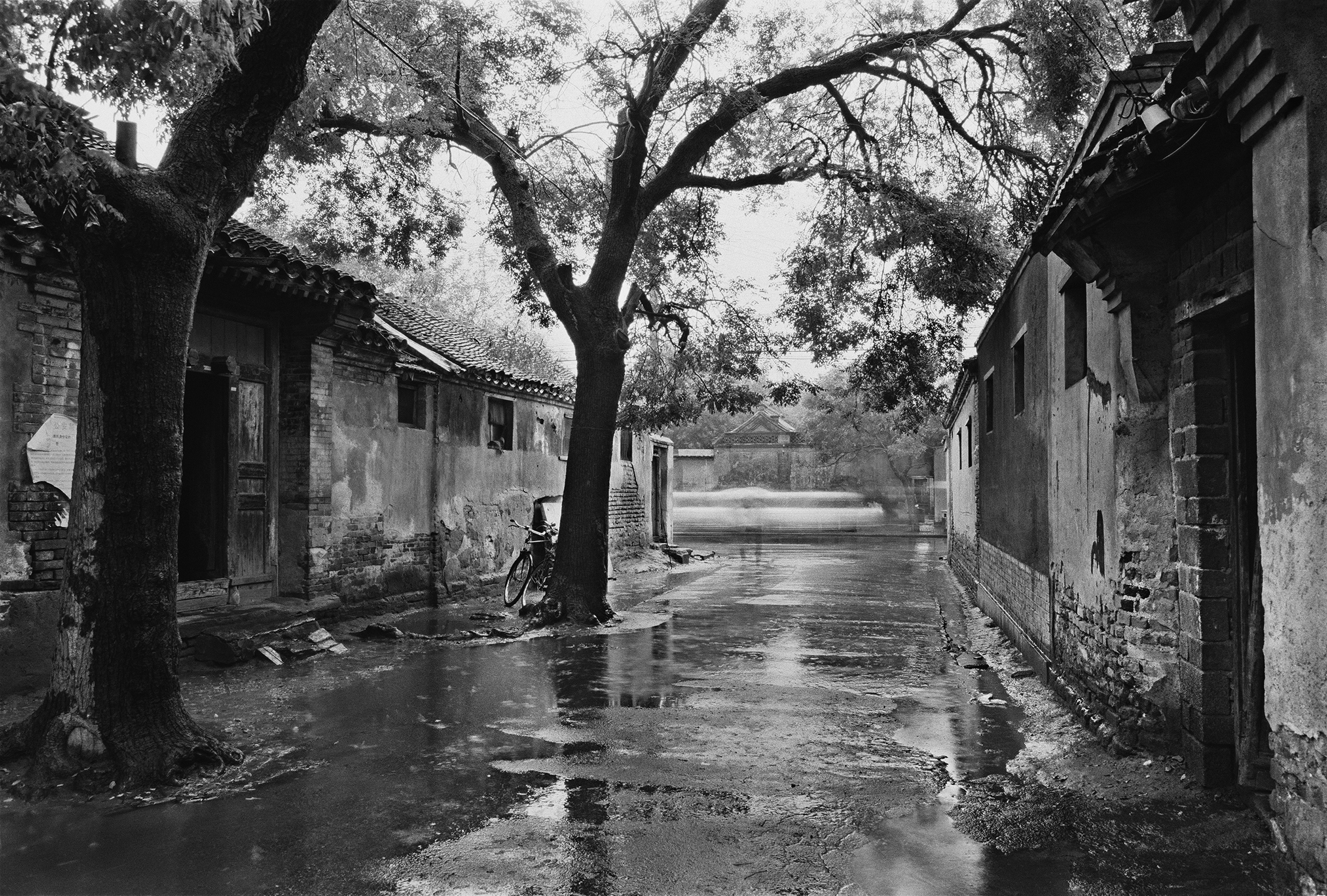

Behind each of these quiet photographs is a tumult of history. Not all of the stories can be openly discussed in China itself. Consider the period when Xu Yong documented these hutong: from June 1989 to the northern spring of 1990, in other words, right after the massacre of hundreds and perhaps thousands of unarmed protesters by the People’s Liberation Army under orders from Deng Xiaoping and Li Peng. [See also Xu’s book Negatives 底片, a collection of his work on the 1989 protests. — Ed.]

In one month from today, on the 4th of June, it will be the twenty-eighth anniversary of the Beijing Massacre. Joy and life but also pain and sorrow run through these narrow lanes. The bulldozers can knock down walls and homes and the hutong themselves, and they do, but I like to believe, anyway, that nothing can destroy the spirit of the city that lives within them, a spirit captured wonderfully in the haunting works here.

Author’s Note: I would like to thank the editor of

China Heritage for his suggestions and revisions to this text.

***

My Home Is Next to Tiananmen Square

Zhang Langlang

張郎郎

Translated by Geremie Barmé with Linda Jaivin

Our small courtyard house is just off Nanchizi Road, right next to Tiananmen. Everyone agrees it’s a very special place.

It the tiniest courtyard imaginable, but somehow there’s room enough in it for a big tree of heaven, with a trunk as thick as a washbasin. Our friends envy us; the whole courtyard is shaded by the leafy parasol of the tree. And it gives us fruit every year… .

Friends and relatives who came visiting could find us just by following the scent of the tree. They came in groups — well, packs really — armed with their baskets and bags. They walked straight in and went clambering up the tree without a by-your-leave. There were always people around at that time of year, up in the tree or gathered beneath, talking or playing, joking and laughing. The fruit rained down on the courtyard. Nobody ever went away empty-handed, dissatisfied. But they always left a dish of the best fruit, saving us the trouble of picking it ourselves. A grand tree, that. This was in early spring, when the weather can turn hot and cold without warning.

When the real spring came, our lilac tree stole the limelight. A few white flowers would permeate the whole alley with their fragrance, so sweet it would follow you down the street, filling your lungs. You could never get too much of it. I suppose that’s why they put it into medicine. The fragrance itself is like a tonic.

***

In the early morning we’d go out to do our exercises. The old people and kids living along the alley would all be up and about as well, calling out a greeting and smiling as you walked past. In Peking they say neighbours are closer than relatives.

Every day, regardless of the weather, there’d be groups of young and old men by the red walls of the old palace, brandishing their spears and cudgels, practicing with as much conviction as if they were really fighting. Even the old man in the white jacket, who used to stay behind closed doors for the rest of the day, would be out there doing his tai chi, convinced he was every bit as good as Grand Master Zhang Sanfeng. You couldn’t help admiring him for his total dedication. He didn’t think much of us joggers — too newfangled and Western for him. But to give him his due, he’d always give us the thumbs-up anyway, just to encourage us. We’d smile back, and that’d make him happy. To him we’d always be kids.

The Cultural Palace is just a short run from our place. We call it ‘our backyard’; it really is the cheapest imperial garden in the world: three cents a head to get in. I won’t bore you by listing all the types of trees and plants in the park; there must be a hundred of those massive pines, the ones that take several people with outstretched arms to reach around. There’s no other place that can compare with it. It’s very special; worth every cent.

In the morning haze, gaggles of old men and women gather to practice the mysteries of qigong. They belong to every school and sect, and they each think they’re the best. Just eavesdrop on any one of the groups talking among themselves for a few minutes, and I guarantee you’ll go away in hysterics.

By the imperial canal just outside the palace, you’ll find people doing voice training; nowadays fewer of them practice Peking opera, they all do bel canto. Fattening their tongues to sing foreign songs, warbling away like nobody’s business. By the time the sound reaches the imperial yellow tiles on the turrets or the emerald leaves of the willows by the red palace walls, you can be sure it will have warbled itself out of key. This must rate as one of the new ‘sights’ of Peking.

In the evening we’d go out for a stroll with my younger brother’s family — they’ve just had a baby girl, so they push her along on a bike. The pack of us would go clomping down the street in our thongs and have a ‘spin’ around the square. The silken evening breeze seemed to summon everybody out of doors: the old and the young, many of them charging around flying kites: ‘paired swallows’, ‘black woks’, ‘split pants’. Some people are only happy flying massive things: great big ‘centipedes’, huge ‘flying hexagrams’, or ‘double dragons’. A bobbing flotilla filled the sky. The high flyers stood there looking very proud of themselves, while the spectators added their tuppence, commenting on each of them. If by accident a couple of kite strings got twisted, there’d always be people ready to help get them untangled; there’d be people waiting to start a fight; and there’d be others to smooth things over… . The whole business is all very good for you, really: gets rid of bile, keeps the juices running, quenches your thirst… . An evening stroll on the square was an essential part of our daily life.

One turn around the square with us, and friends from Hong Kong and Taiwan were converted. They praised it to the skies, each in their own unbearable out-of-key attempt at a Peking accent. They weren’t joking, either: Who else had a massive courtyard like Tiananmen Square right on their front doorstep? That the way we are : Peking people are used to space, and lots of it. Our hearts are bigger than most, can never get use to the small-minded.

Our lives have been linked with those streets, that huge garden, the square; they are all part of us.

***

Then the students came. When we heard them sing their songs, our hearts beat faster. Tears filled our eyes when we heard them speak to the crowds, their voices growing hoarse. We felt sick at heart when we heard they were going on a hunger strike.

What did they want? It was something for us; they wanted something more for all of us. Each of us could judge in his own heart; no one could deny the justness of their cause. They’ll win for sure, we thought. Our fathers and grandfathers had always been so submissive, they’d never had the courage of the students. Even though they’d wanted the same things.

People said they were all from outside Peking, but we treated them like they were our own children. They were polite, a little shy, just kids. We’d drag them into our courtyard and give them a drink. They’d always say: a glass of cold water would be fine. But we’d always prepare some jasmine tea; too hot for them, they’d say, then we’d add some cold boiled water to the cup. Sometimes they wouldn’t even wait for it to cool off.

When the people from our alley, men and women, old and young, went out to keep the army from getting to the square, none of them were scared in the least. They didn’t give a thought to the danger. All we knew was: ‘We are Peking people, we can’t let the army beat up the students on our own doorstep, can we?’

Later … but I can’t go on. What use is what I have to say? They didn’t just beat up the student, they killed them. They murdered our neighbours too. Remember that old man who did tai chi every morning? The old boy never bothered anyone in his whole life, all he ever wanted to do was practice his shadowboxing in peace. Well, he’s gone. Just like that.

And what about those kids who came up our alley for a drink of water? Which of them survived? No one knows. And the road outside our alley. All torn up by the tanks. And the square… Words aren’t enough. But we’re not sad, not now. Now we understand. It’s too late for talk.

One day the road will be repaired, the square resurfaced, hosed down, cleaned up. But how can we go out for our morning exercise as though nothing had ever happened? How can we take a stroll around the corner to the square or go flying kites? … How can we ever be happy here again?

I’d never seen such a thing before, never even thought it possible. No one in that city could ever have imagined it.

We shouldn’t have had to witness so much. But one day, one day…

This translation originally appeared in Barmé and Jaivin, New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, New York: Times Books, 1992, pp.111-115. The Chinese original was published in the July 1989 issue of the Hong Kong journal The Nineties Monthly 九十年代月刊.

Zhang Langlang was born in the wartime Communist base at Yan’an in 1943, the son of Zhang Ding 張仃, a famous painter and a veteran Yan’an cadre, and Chen Buwei 陳布偉, a writer. (Zhang Ding was one of the principal designers of the national emblem of the People’s Republic that hangs on the Gate of Heavenly Peace overlooking Tiananmen Square.) In his twenties, Langlang was imprisoned for various counterrevolutionary activities (joking about Party leaders; nonconformist poetry and spreading satirical stories about the Party). He later became a successful businessman and publisher, as well as writing a column for The Nineties. Following the 4th of June 1989, Langlang quit Beijing and thereafter held various teaching positions in North America and Europe. His account of growing up in a famous hutong, Memories of Yabao Alley 大雅寶舊事, appeared in 2004.

The linked commemorative essays related to the 4th of June in China Heritage are:

- Memory Holes, old & new

- The Double Fifth and the Archpoet

- Child’s Play — 1st of June

- The Gate of Darkness