The Rings of Beijing

Sang Ye 桑曄 and Geremie R. Barmé (GRB), The Rings of Beijing, Inside China’s Global Aura, an oral history account of China and the Chinese capital. The book is organised spatially and thematically around the six ring roads (and the seventh ‘nimbus of garbage’) of Beijing.

To date, the following translations, with introductory material, have been published online:

- Wang Dan: Accounting for 111 Years, GRB

- Bai Jian: The Torchbearer, GRB

- Teacher Zhang: A Window on the Forbidden City, translated by Linda Jaivin, with GRB

- Yang Zhiyuan: Huang Shan, Selling Scenery to the Bourgeoisie, GRB

- Zhai Quan’an: The Han Supremisist, GRB

- The Taxi Driver: Driving in Circles, GRB

- Zhao Hang: 1949-2009, Sixty Years Under the Radar, GRB

- Lü Shunfang: Fifty-thousand Orphans and the Way Home, translated by Linda Jaivin

Tracks in the Snow

To what should we compare human life?

It should be compared to a wild goose trampling on the snow.

The snow retains for a moment the imprint of its feet;

the goose flies away no one knows where.

– Su Shi, trans. Simon Leys

人生到處知何似。

應似飛鴻踏雪泥。

泥上偶然留抓痕。

鴻飛那復計東西。

— 蘇軾

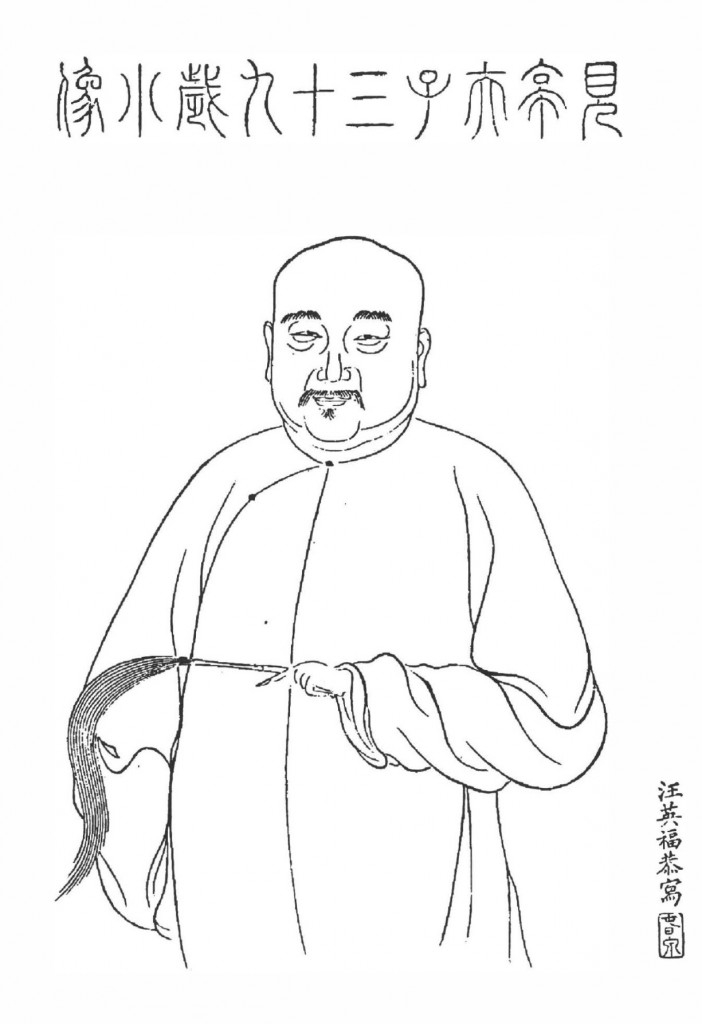

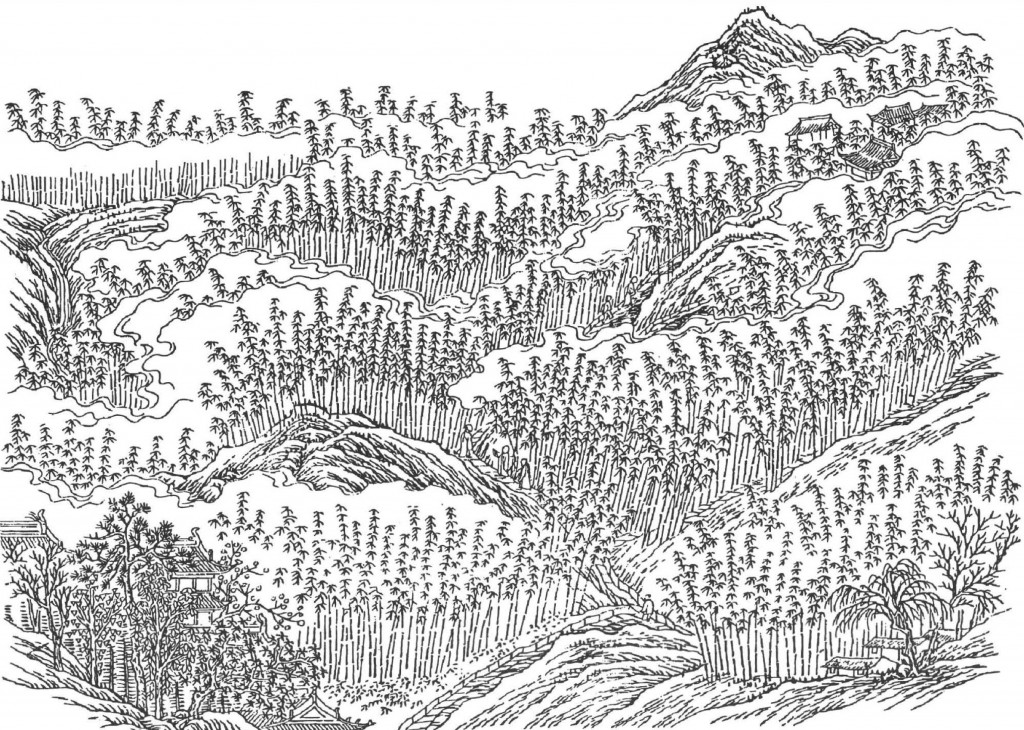

The translation of the mid-Qing-dynasty Manchu Bannerman Lincing’s (Linqing 麟慶, 1791-1846) Tracks in the Snow 鴻雪因緣圖記 was undertaken by Yang Tsung-han 楊宗翰 at the suggestion of John Minford in the 1980s. Further work was done on these translations by Rachel May. Since 2015, Christina Sanderson has been collating and revising Professor Yang’s unfinished work and translating the remaining chapters of Tracks in the Snow. This translation with annotations and explication is being undertaken with the support of an Australian Research Council grant awarded to Geremie R. Barmé and John Minford under the title ‘Manchu Rivers, Manchu Mountains’.

Links to previously published chapters from Lincing’s illustrated memoir are provided below. New work will appear as it becomes available. the full translation with illustrations will be published in book form.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

Tracks in the Snow 鴻雪因緣圖記 — Episodes from an Autobiographical Memoir by the Manchu Bannerman Lin-ch’ing 麟慶, translated by Yang Tsung-han 楊宗翰, edited by John Minford, from East Asian History, 6 (December 1993)

- Editor’s Remarks, by John Minford

- Foreword, ‘An Imperfect Understanding — A Memoir of Yang Tsung-han’, by Liu Ts’un-yan 柳存仁

- Preface, by P’an Shi-en 潘世恩

- Witnessing the Alchemic Orbs at Longevity Hall, 延年玩丹

- Presenting Verses to my Parents in the Gallery Ringed by Verdure 環翠呈詩

- Studying the Classics in Serenity Hall 靜存受經書

- Recollecting a Dream of the Temple of Gracious Clouds 慈雲尋夢

- Paying my Compliments to West Lake 西湖問水

- Practising Zen in the Monastry of Purity and Grace 淨慈坐禪

- Treading the Emerald Shade to Hidden Light Hermitage 韜光踏翠

- Watching the Ch’ien-t’ang Bore 錢塘觀潮

- Luring Fish at Jade Spring 魚引泉玉

More Tracks in the Snow (Renditions, Spring 1999)

- Introductory Note

- Climbing to Enjoy the Fragrance of the Garden of Good Cheer, Episode 23

- Seeking Out the Beauty of Orchid Pavilion, Episode 25

- Greeting the Crane in the Prefectural Garden, Episode 34

- Exploring the Beauty of the Sui Garden, Episode 51

- Verifying Documents in the Hall of Pomegranates, Episode 86

- Reminisces of the Past and the Tower of Lyric Incantation, Episode 137

- Enjoying the Cool in the Lotus Pavilion, Episode 145

- Sailing in the Boat ‘Green Wilderness’, Episode 153

- In Quest of Flowers at the Priory of the Twin Trees, Episode 154

- A Tea Party at the Peach Spring Fountain, Episode 155

Further Tracks in the Snow (China Heritage Quarterly)

- Mengxiang Discoursing on the I Ching 夢薌談易, Episode 44

- Observing the Rites at the Ancient Abode of Confucius 闕里觀禮, Episode 35

- Singing with the Spring, Tracks in the Snow

- Exploring the Beauty of the Sui Garden 隨園訪勝, Episode 51

The Teddy Bear Chronicles

In 1989, the Hong Kong writer Xi Xi 西西 was diagnosed with breast cancer. Post-operative treatment damaged the nerves in her right hand, but she taught herself to write with her left and, in 1992, she published Elegy for a Breast 哀悼乳房 (adapted for the screen as 2 Become 1). Later on, in an effort to regain movement in her affected hand, Xi Xi focussed on handicrafts. Over the years, she crafted dolls houses, puppets and stuffed animals, and eventually teddy bears. Her bears started out within the familiar tradition of the Western teddy — the toy bears inspired by Theodore (Teddy) Roosevelt in the 1900s and Winnie-the-Pooh in the 1920s — but over time Xi Xi developed her own, uniquely Chinese breed.

The Teddy Bear Chronicles 縫熊志 appeared through Joint Publishing HK in 2009. It consists of short essays influenced by the biographical style, or 列傳, of Sima Qian 司馬遷 (206 BC-220 CE), the Grand Historian of the Han dynasty. Xi Xi matches her biographical sketches with images from her ursine pantheon of handmade teddies.

This Teddy Bear’s Picnic includes mythological figures such as the Queen Mother of the West 西天王母, as well as Hou Yi 后羿 and Chang’e 嫦娥, along with historical personalities like the Taoist thinker Zhuangzi 莊子, the disaffected courtier-turned-poet Qu Yuan 屈原, the historian Sima Qian himself, the calligrapher Wang Xizhi 王羲之, the recluse Tao Yuanming 陶淵明, as well as the mauruding emperor Genghis Khan 成吉思汗. Xi Xi also found inspiration in the heroes of the popular Ming-dynasty novel Water Margin 水滸傳. Some prominent figures from the West share the spotlight, too, including Julius Caesar and Cleopatra; there’s even a suave Lawrence of Arabia. All the teddies wear costumes designed and made by Xi Xi.

Xi Xi is one of those rare artists who has the genius to make the old new again. It is a talent that she has nurtured in (and that thas been nurtured by) Hong Kong.

The Teddy Bear Chronicles is an ecumenical fancy-dress ball; Xi Xi sent out all the invitations, she wrote the script and dressed the guests. It is with great pleasure that below we introduce our readers to ‘Zhuangzi’, a teddy bear tale inspired by the great philosopher who lived around the fourth century BCE, during the Warring States period.

Xi Xi is the pen name of Cheung Yin 張彥, one of Hong Kong’s most beloved and acclaimed writers. She says that the Chinese characters of her pen name, 西西, look to her like a girl playing a Chinese form of hopscotch in a skirt. Her creative work is a delicate admix of the naïve and the absurd. Regarded as a pioneer of experimental filmmaking and screenwriting in the 1960s, Xi Xi went on to publish two collections of poetry, seven novels, twenty-one short story and essay collections and one stand-alone novella. Her essays have also frequently appeared in the popular press, as have her translations.

Xi Xi is the second of five children born in 1938 to Cantonese parents in Shanghai. The family migrated to Hong Kong in 1950 shortly after the founding of the People’s Republic on the mainland. Following high school and graduate education, she worked as an English teacher at a government primary school. Living in the cultural and trading entrepôt of Hong Kong and comfortable in several languages, Xi Xi was exposed to world literature and culture from an early age and she cites the main influences on her work as being children’s writing, film and Latin American and European literature.

***

This introductory note is based on material provided by Christina Sanderson, translator of The Teddy Bear Chronicles. It also incorporates information from Jennifer Feeley’s introduction to Not Written Words 不是文字, a selection of Xi Xi’s poetry in translation.

We are grateful to Christina for sharing this new work with our readers, and to John Minford who introduced us all to Xi Xi’s panoply of bears. The translation of The Teddy Bear Chronicles will appear as a volume in a series under John’s editorship. That series is generously funded by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council.

The photographs of Xi Xi’s teddies are by Chan Kum-lok 陳錦樂 and Lum Kwok-wai 林國威.

We look forward to introducing more teddy bears from Xi Xi’s chronicles in the future.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Zhuangzi 莊子

Zhuangzi was a fascinating individual with more stories up his sleeve than anybody else in the world. Some of his stories are long, others are short; but they’re all interesting and superbly imaginative. They’re also full of paradoxes — to use a favourite expression of his (even though it’s become a terrible cliché). In one instance, a gigantic bird capable of flying ninety thousand li in one flap of the wing turns out to be the transformation of a miniscule fish. In another, a massive gourd that was hopeless as a water jug could well serve as a sailing boat. Then there’s that huge, useless tree, which delights in being considered useless. Since nobody wants it for anything, it can come to no harm. Why wouldn’t it be happy about that?

莊子真是世界上最多故事的妙人。他的故事大大小小,有趣,充滿想像,充滿,用他的詞匯雖然這詞匯已濫得有點肉麻:弔詭。例如有時是很大很大的鳥,一飛九萬里,可這大鳥是從一尾很小很小的魚變成的。有時是很大很大的葫蘆,可不要用來盛水,而是最好當遊船﹔有時呢是一棵沒用的大樹,你說它沒用,它可高興了,你就不會打它的主意,損害它,它豈不悠哉游哉。

Zhu Guangqian, who founded the study of aesthetics in modern China, wrote an essay discussing three ways to look at ancient pine trees. It’s interesting enough. But aeons before this, Zhuangzi had already introduced another, completely different point of view: that of the tree itself. Once we can imagine a tree with its own own point of view, then we won’t go around thinking ourselves better than trees, or imposing our will upon them. From then on, we will respect trees. Starting from a sense of respect for trees, we can go on to respect other things.

朱光潛以往寫過篇三種角度看一棵古松的文章,很有意思﹔不過三種角度都把樹木對象化,莊子老早告訴我們,其實還有另外一種角度﹕樹木自己的角度。如果想到還有這麼一個樹木本身的角度,你就不會看輕樹木,不會對樹木強加自己的主觀意志,從而尊重樹木。從尊重一棵樹木出發,你就會懂得尊重其他。

Zhuangzi is constantly teaching us how to see things differently: from the opposite angle; from the contrary point of view. The idea is to reveal how not to be stubborn, biased, or prejudiced. In one case, he asks: How can a summer-born bug whose life spans just a single season, ever hope to understand ice or snow? He goes on to explain why the summer bug has no way of understanding such things. It should be aware of its limitations, and accept the possibility of other points of view. It shouldn’t go around judging things related to other seasons from its own limited perspective, that of a summer bug. Humans perpetuate the error made by the summer-born bug, and have been doing so for more than two thousand years.

莊子總是教我們用不同的角度看物事,相反的角度,逆向的角度,不要偏執成見。試想想,生長一季的夏蟲,如何明白冰雪是什麼。這是夏蟲沒有辦法的事,但牠至少要知道自己的局限,其他角度的可能,不要死抱夏蟲之見去判斷另一個季節的物事。二千多年來,我們人類的社會,仍然犯著夏蟲的毛病。

They say that a certain monarch once offered Zhuangzi the post of Prime Minister. He refused. Now that is an earnest renouncement of fame and fortune. His stories were certainly not idle chit-chat. He practised what he preached.

據說某某國君想請他做宰相,他拒絕了,這是對名利真正的捨棄。他的故事,可不是說說就算。

Sometimes Zhuangzi himself becomes the protagonist of his stories. The most famous is about a dream he once dreamed. He dreams of a butterfly, then imagines himself as the butterfly; until he no longer knows whether he is Zhuangzi dreaming of a butterfly, or a butterfly dreaming of a man called Zhuangzi. It has to be the best dream in history. Since when did we stop having wonderful dreams like that? Since when did our dreams become nothing more than objects for psychopathology?

有時,莊子連自己也成為故事的主人翁,最著名的是他一次做夢,夢見蝴蝶,於是從蝴蝶設想,到頭來不知是莊周夢見蝴蝶,抑或是蝴蝶夢見莊周。這夢,真是人類最甜美的夢。什麼時候,我們失去了這種美夢呢?什麼時候,我們的夢,成為病態心理學分析的對象?

The Zhuangzi bear I’ve made is most likely dreaming of butterflies in his sleep, too. You’ll see he has a wawa pillow, with a doll’s face at either end. Where is he sleeping? Under a big tree? On the grass? Just as a butterfly would, he has perched himself on top of a hedge for a nap.

我縫的莊子在睡覺時夢見蝴蝶了吧。他枕的是「娃娃枕」,兩頭各有一張娃娃臉。他睡在哪裡?大樹下,草地上?原來他一如蝴蝶,睡在一叢樹籬的頂端。

Xi Xi in the Bamboo Grove: Xi Kang and Ruan Xian

Here we introduce two more figures in The Teddy Bear Chronicles 縫熊誌, created by the Hong Kong writer and teddy bear artist Xi Xi 西西 and translated by Christina Sanderson.

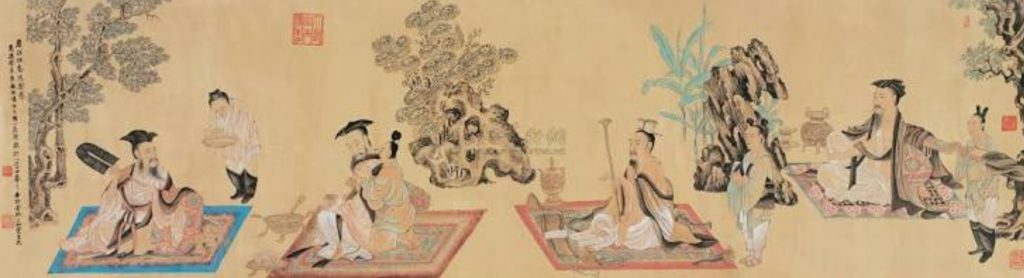

The teddies and essay below feature Xi Kang 嵇康 and Ruan Xian 阮咸, two of the famed Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢. This informal group of free-wheeling individuals flourished during the Wei-Jin period, that is, in the Fourth Century of the Common Era. That era is also a feature of our inaugural China Heritage Annual, which takes Nanking as its focus.

Xi Kang is also one of the guiding spirits of China Heritage; his personality and words inspired On Heritage 遺, an essay that offers a Rationale for The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology.

One of our China Heritage projects is to introduce Xi Xi’s Chronicles in translation and we are grateful to Christina for continuing to share her work with our readers, and to John Minford who introduced us all to Xi Xi’s panoply of bears. The full translation of The Teddy Bear Chronicles will appear as a volume in a series under John’s editorship. That series is generously funded by the Hong Kong Arts Development Council.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

The seven used to gather beneath a bamboo grove, letting their fancy free in merry revelry. For this reason the world called them the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 七人常集於竹林之下,肆意酣暢,故世謂竹林七賢。

— Liu Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444CE), New Sayings of the World 世說新語, trans. Richard B. Mather

The Six Dynasties was a period of chaotic disunion when northern China was in the hands of non-Chinese leaders and the south was ruled by a succession of weak and short-lived dynasties. The work of poets and artists of this era reflects the unease and anxiety of Chinese society at the time. Many literati tried to escape the atmosphere of corruption and intrigue by moving away to the country, where they would indulge in drinking, music and poetry. Xi Kang, (aka Ji Kang 223-262) and Ruan Xian are two of a famous group of scholars, writers and musicians said to have done just this, known as the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. They are alleged to have gathered in a bamboo grove near the house of Xi Kang in Shanyang (in present-day Henan province) where they celebrated the simple, spontaneous things in life. Although Xi Kang married into the Imperial family, and received an offiical appointment, his favourite study remained that of alchemy and forging iron (apparently, ‘to imitate the activity of the Tao, the Great Smith’). Happening to offend one of the Imperial princes, who was also a student of alchemy, he was denounced as a dangerous person and a traitor and condemned to death. Three thousand disciples offered themseleves in his place, to no avail. He met his fate with fortitude, calmly watching the shadows thrown by the sun and playing upon his zither.

From Herbert Giles, A Chinese Biographical Dictionary, Shanghai, 1898, with modified romanisation

Xi Kang and Ruan Xian of the Six Dynasties

Xi Xi

Translated by Christina Sanderson

Passing a music shop one day, I saw a display of several miniature musical instruments. I went in and chose two, and then went home to make teddies of some of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove. 經過樂器店的飾櫥,見到窗櫥內陳列了幾件微型樂器,進去選了兩件,回家縫竹林人物。

Xi Kang played a seven-stringed zither 琴. The body of the instrument has a wide end called the head and a narrow end called the tail. Along the side of the finger board are thirteen small white dots 徽, which mark different notes in the scale. The finest quality ones are made of jade, and the best strings are made of silk. When he was faced with imminent execution, Xi Kang played a tune on his zither called the ‘Melody of Guangling’, Guangling San 廣陵散. ‘San’ 散 is the name of this type of free melody; Guangling was a place in the present-day city of Yangzhou in Jiangsu province. The music tells the tragic tale of vengeance of Nie Zhen, who assasinated Xia Lei, the Prime Minister of the small state of Han, during the Warring States period. 嵇康彈的是七弦古琴,一般有七弦。琴身頭寬尾窄,面板外側有十三粒小白圓點,稱徽,是音階的標誌。第一等的徽用玉製,弦用蠶絲。嵇康在臨刑時彈《廣陵散》。散是曲名,廣陵是地名,即今江蘇揚州。樂曲是復仇者的頌歌,敘述戰國時聶政刺殺韓相俠累的悲劇。

During the Wei-Jin period, distinguished men of letters 名士 dressed unconventionally. They enjoyed taking their clothes off. Men wore skirts just like women and tied their hair up. Xi Kang is wearing a special sort of skirt featuring a shoulder strap. His hair is done up in a top-knot, which I fashioned according to one of the clay brick impressions of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove found near Nanjing. I think the zither in the brick impression is the wrong way around. Perhaps it was deliberately sketched that way when it was being carved so that Xi Kang could sit facing Ruan Ji. 魏晉名士衣飾不落俗套,喜坦膚裸體,男子也著裙,梳了角髻。嵇康穿攀帶裙。頭紮卯髻,我讓髮式依循漢磚壁畫《竹林七賢》的圖照。畫中的古琴我想擺錯了方向,不知是否刻蝕時圖稿故意反轉了,要配合和阮步兵相向而坐?

Ruan Xian is playing a plucked string instrument with a long neck. These are normally called ‘moon lutes’ 月琴 after the round shape of the body. Since Ruan played one, they are sometimes called ruan after him. It was the precursor of the more famous, upright lute-like instrument called the pipa 琵琶. Ruan’s moon lute had twelve frets and he used a bamboo plectrum to pluck the strings. 阮咸撥的是圓月形有長項的琴,一般叫月琴,因為阮咸奏過,琴以人傳,稱阮咸。它是琵琶的前身。阮咸的阮有回弦十二柱,他用竹片撥。

I had his hair loose, but it hung down over his face. So I just clamped it back with a peg, which looks very post-modern. Like Xi Kang, he’s wearing a skirt with a shoulder strap, too. They are both wearing a special kind of decorative shawl. 我讓阮咸披髮,額前髮絲會垂掛遮面,就用個晾衣夾咬住,十分後現代。和嵇康相同,他也著攀帶長裙。二人都披一幅特別的巾帔。

There are two famous paintings, Northern Qi Dynasty Scholars Collating Cassic Texts and Gentlemen in Retirement which feature groups of literati, all wearing skirts with shoulder straps and semi-circular chiffon shawls extending down below the waist. The shawl is draped around the back of Ruan’s shoulders, with the ends hanging in front of his chest. There is a pair of silk ribbons which can be used to tie the ends of the shawl together. It really is a very beautiful garment. It’s like the silken head scarf worn by the master strategist Zhuge Liang who was known to carry a fan made from crane feathers. After all, who’s to say head scarves have to be worn on the head? 《北齊校書圖》和《高逸圖》中有一群文士,個個穿吊帶裙,身披一幅半圓形垂到腰以下透明的紗羅披肩。披巾搭繞在肩背上,兩隻角垂在胸前,兩襟綴有一對帛帶,可繫結住巾角。這件衣物真是漂亮出眾,可能就是羽扇綸巾的巾。誰說綸巾一定是紮在頭上的呢。半個輪形的巾可不就是綸巾。輪、綸相通。