Watching China Watching (VII)

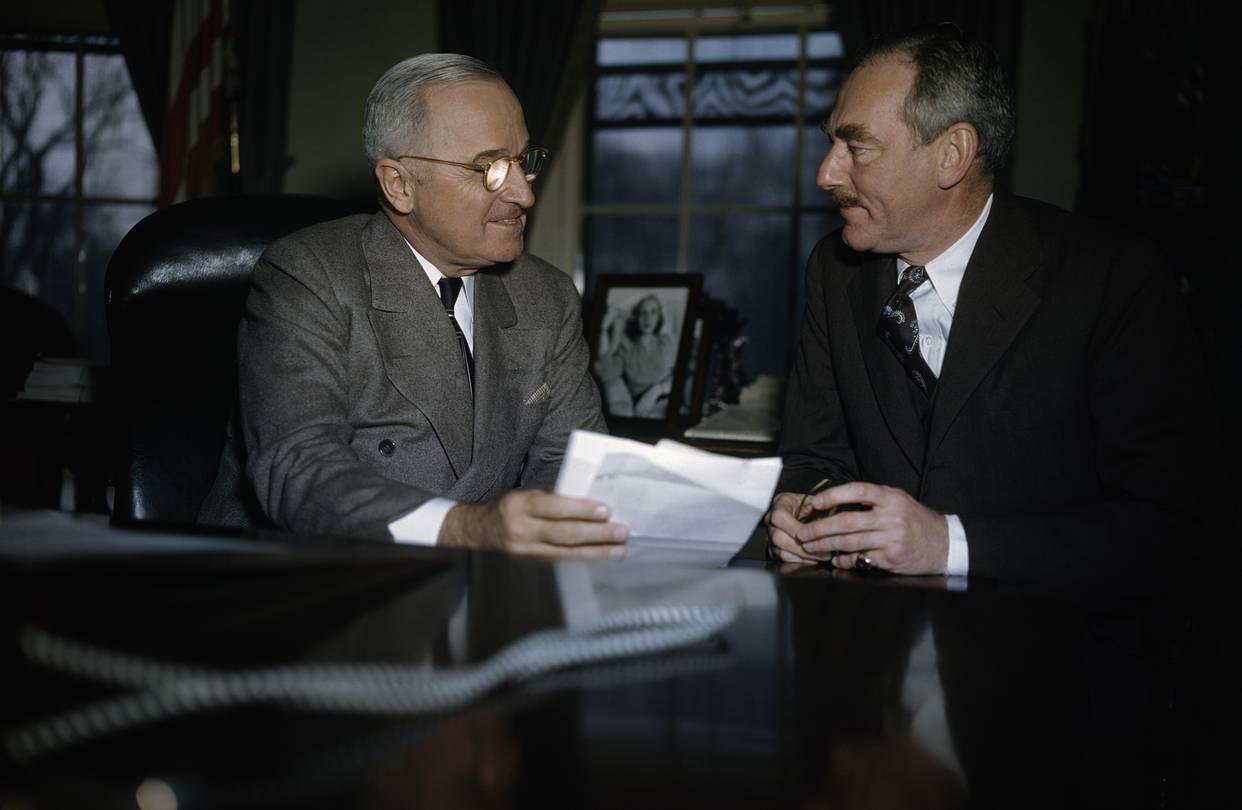

In 1949, the civil war on mainland China entered its final phase. The People’s Liberation Army under the command of the Communist Party was on the march to overthrow the Republic of China under the leadership of Chiang Kai-shek and his Nationalist Party. On 5 August 1949, the eve of the Communist victory on mainland China, the American Department of State released United States Relations With China, With Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949, known simply as the China White Paper. It was prefaced by a Letter of Transmittal (titled ‘A Summary of American-Chinese Relations’) to President Truman dated 30 July from Dean Acheson, the US Secretary of State.

As the historian Lyman Van Slyke writes in his 1967 introduction to that work:

The White Paper was … published in the midst of acrimonious controversy over United States China policy, the containment of Communism abroad, and the fear of subversion at home. … …

The directive from President Truman and Secretary Acheson to the compilers of the White Paper called for a completely objective record. Yet the Administration plainly hoped this record would show that we had done as much as we could, that our course had been basically correct, and that the impending fall of China to the Communists was in no way attributable to American policy. The White Paper was issued to counter largely Republican criticism. In Truman’s words, ‘The role of this government in its relations with China has been subject to considerable misrepresentation, distortion, and misunderstanding. Some of these attitudes arose because this government was reluctant to reveal certain facts…’ Truman believed his two goals — objectivity and justification — were compatible. His critics, as it turned out, found the White Paper neither objective nor convincing.

— Lyman P. Van Slyke, Introduction,

United States Relations With China,

With Special Reference to the Period 1944–1949

***

In the annals of ‘China Watching’, the White Paper is an extraordinary document. The immediate political and policy significance of that voluminous work (it runs to over 1000 pages) is obvious: it was written to justify American policies, and failures, in China. Yet it was also a decoction of expert China watching undertaken by policy thinkers, military men, academics and intelligence officers over many years.

In his Letter of Transmittal dated 30 July 1949, which acted as a preface to the White Paper, Dean Acheson declared that:

It must be admitted frankly that the American policy of assisting the Chinese people in resisting domination by any foreign power or powers is now confronted with the gravest of difficulties. The heart of China is now in Communist hands. The Communist leaders have fore-sworn their Chinese heritage and have publicly announced their subservience to a foreign power, Russia, which during the last 50 years, under czars and Communists alike, has been most assiduous in its efforts to extend its control in the Far East. In the recent past, attempts at foreign domination have appeared quite clearly to the Chinese people as external aggression and as such have been bitterly and in the long run successfully resisted. Our aid and encouragement have helped them to resist. In this case, however, the foreign domination has been masked behind the façade of a vast crusading movement which apparently has seemed to many Chinese to be wholly indigenous and national. Under these circumstances, our aid has been unavailing.

The unfortunate but inescapable fact is that the ominous result of the civil war in China was beyond the control of the government of the United States. Nothing that this country did or could have done within the reasonable limits of its capabilities could have changed that result; nothing that was left undone by this country has contributed to it. It was the product of internal Chinese forces, forces which this country tried to influence but could not. A decision was arrived at within China, if only a decision by default.

And now it is abundantly clear that we must face the situation as it exists in fact. We will not help the Chinese or ourselves by basing our policy on wishful thinking. We continue to believe that, however tragic may be the immediate future of China and however ruthlessly a major portion of this great people may be exploited by a party in the interest of a foreign imperialism, ultimately the profound civilization and the democratic individualism of China will reassert themselves and she will throw off the foreign yoke. I consider that we should encourage all developments in China which now and in the future work toward this end.

The 1949 White Paper included in its documentary coverage of the period 1944-1949 a summary of the Wedemeyer Report, submitted to President Truman two years earlier, in November 1947. Authored by a group led by General Albert C. Wedemeyer, who assumed command over US forces in China following the dismissal of Joseph Stilwell in October 1944, the report offered a clear-eyed assessment of the Chinese civil war. The preamble was eloquent in its simplicity:

Notwithstanding all the corruption and incompetence that one notes in China, it is a certainty that the bulk of the people are not disposed to a Communist political and economic structure. Some have become affiliated with Communism in indignant protest against oppressive police measures, corrupt practices and maladministration of National Government officials. Some have lost all hope for China under existing leadership and turn to the Communists in despair. Some accept a new leadership by mere inertia.

— ‘Report on China-Korea’, 1947,

Appendix VI in Albert C. Wedemeyer,

Wedemeyer Reports!, New York: Holt, 1958, p.464.

And, in the following political analysis of China, the report warns of a situation that would bedevil the authors of the 1949 White Paper:

Although the Chinese people are unanimous in their desire for peace at almost any cost, there seems to be no possibility of its realization under existing circumstances. On one side is the Kuomintang, whose reactionary leadership, repression and corruption have caused a loss of popular faith in the Government. On the other side, bound ideological to the Soviet Union, are the Chinese Communists, whose eventual aim is admittedly a Communist state in China. Some reports indicate that Communist measures of land reform have gained for them the support of the majority of peasants in areas under their control, while others indicate that their ruthless tactics of land distribution and terrorism have alienated the majority of such peasants. They have, however, successfully organized many rural areas against the National Government. Moderate groups are caught between Kuomintang misrule and repression and ruthless Communist totalitarianism. Minority parties lack dynamic leadership and sizable following. Neither the moderates, many of whom are in the Kuomintang, nor the minority parties are able to make their influence felt because of National Government repression. Existing provincial opposition leading to possible separatist movements would probably crystallize only if collapse of the Government were imminent.

Soviet actions, contrary to the letter and spirit of the Sino-Soviet Treaty of 1945 and its related documents, have strengthened the Chinese Communist position in Manchuria, with political, economic and military repercussions on the National Government’s position both in Manchuria and in China proper, and have made more difficult peace and stability in China. The present trend points toward a gradual disintegration of the National Government’s control, with the ultimate possibility of a Communist-dominated China.

— ‘Report on China-Korea’, 1947, pp.467-468

In the event, the Wedemeyer Report was not publicly released and its recommendations (including a diplomatic effort to stall Soviet expansion in Manchuria, urgent measures to shore up support for the Nationalists and a generous aid program for economic reconstruction) were not pursued.

***

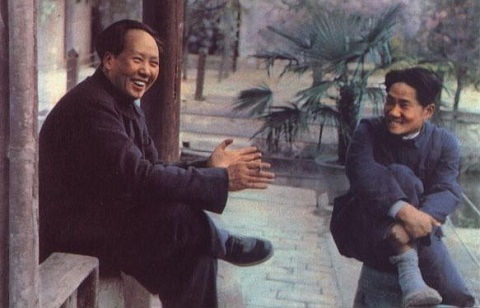

Although the 1949 White Paper came as a heavy blow to its hope of maintaining a foothold on mainland China, the Chinese Republic, in the person of Soong May-ling 宋美齡, Madame Chiang, wife of the ‘retired-but-not resigned president’ Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, continued lobbying Washington in favour of the Nationalist cause. For his part, Chiang’s opponent and leader of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao Zedong, responded to the White Paper with a series of withering, latterly ‘canonical’, essays — canonical in that these writings remain an important part of China’s foreign policy vade mecum — composed at Shuangqing Villa 雙清別墅 in the Western Hills outside Beiping 北平 (later Beijing), his redoubt for most of 1949.

In an editorial published by Xinhua News Agency and in five signed articles, Mao with the help of his chief propagandist Hu Qiaomu (see below) offered a Marxist-Leninist analysis of US China policy — and for that matter China watching. The White Paper might have been an attempt at an objective review of US-China policy, but for Mao and the Communists, it was a blatant admission of US imperial designs in China, as well as a blatant admission as to the extent Washington had bankrolled the now bankrupt Nationalist cause (over the coming decades, the Communists would observe America replicating this faulty strategy when meddling with countries as diverse as Vietnam and Iraq, to name only two). These six Maoist texts are lapidary in nature: many of Mao’s observations, formulations and comments — along with particular turns of phrase and his masterful use of sarcasm — were soon embedded in China’s evolving political discourse, what I call New China Newspeak. To this day, they continue to inflect the way that the People’s Republic speaks to and about itself. At the time, Mao was quoted ad nauseam in the media of New China. During August and September, the Communists used the tactics of mass mobilisation to launch formal denunciations of the White Paper (sight unseen) in cities under their control. The press published near-hysterical attacks the US plot to suborn China was uncovered. It was the first mass campaign of its kind in yet-to-be-born socialist China.

Mao’s words were also used prophylactically by countless individuals as they accommodated themselves to the new dispensation, straining thereby to reject the United States, its policies and ideals as obligatory performances of self-abnegation and ‘self-renewal’ were organised throughout the country.

***

For the Communist Party the White Paper was a timely ‘negative teaching example’ 反面教材; it not only offered insights into American policy (or at least the policy of key figures in both the Roosevelt and Truman administrations) and its long-term strategic thinking, but it acted as a guide as to how to counter the arguments of the Imperialist West in regard to China’s past, present and future. The editors of Mao’s Selected Works claimed that:

The White Paper and Acheson’s Letter of Transmittal are full of distortions, omissions and fabrications, and also of venomous slanders and deep hatred against the Chinese people. In the quarrel within the U.S. reactionary camp over its policy towards China, imperialists like Truman and Acheson were compelled to reveal publicly through the White Paper some of the truth about their counter-revolutionary activities in an attempt to convince their opponents. Thus, in its objective effect, the White Paper became a confession by U.S. imperialism of its crimes of aggression against China.

Among the devastating consequences of the White Paper and Dean Acherson’s Letter of Transmittal is that for Mao and his fellows they confirmed in no uncertain terms the long-term danger posed to a Communist party-state by ‘democratic individualists’ 民主個人主義, that is men and women trained in or sympathetic to Western values, politics, economic thinking and scholarship. In his response to the White Paper, Mao named a few of the best known pro-West public figures, such as Hu Shi (胡適, 1891-1962), a celebrated academic and the Chinese Republic’s ambassador to Washington from 1938 to 1942.

Shortly before the White Paper appeared — in his ‘On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship’ dated 30 June 1949 and released to commemorate the twenty-eight anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party — Mao had already made it clear that everyone in China was faced with a stark choice: either to support Soviet-style socialism (to ‘lean to one side’ 一邊倒), or to shore up imperialism, represented by the United States:

‘You are leaning to one side.’ Exactly. The forty years’ experience of Sun Yat-sen and the twenty-eight years’ experience of the Communist Party have taught us to lean to one side, and we are firmly convinced that in order to win victory and consolidate it we must lean to one side. In the light of the experiences accumulated in these forty years and these twenty-eight years, all Chinese without exception must lean either to the side of imperialism or to the side of socialism. Sitting on the fence will not do, nor is there a third road. We oppose the Chiang Kai-shek reactionaries who lean to the side of imperialism, and we also oppose the illusions about a third road.

The Third Road (also known as the Third Way 第三條路線 or the Middle Line 中間路線) had been promoted by a broad spectrum of social democrats and others who advocated a political coalition under a Chinese republic that could possibly forge a path between the extremes presented by the hard-line Nationalist Party led by Chiang Kai-shek and the Stalinist socialism advocated by Mao’s communists. In the following years, advocates of moderation and democracy, as opposed to the political extremism that blighted the Chinese world, would be excoriated, both on the ‘liberated’ Chinese mainland and on Taiwan (see, for example, Dai Qing’s 2007 Morrison Lecture, 1948: How Peaceful was the Liberation of Beiping?)

Mao’s essays on the White Paper excerpted below, as well as his comments in subsequent speeches and writings, bolstered the rationale for the ideological and class-based purge of universities, publishers, the media and intellectual worlds. In the early 1950s, the effect on China’s intellectual and cultural life was devastating: during the reorganisation of universities and the ideological campaigns related to the films The Secret History of the Qing Court 清宮秘史 and The Biography of Wu Xun 武訓傳, as well as in the far-reaching 1954 cultural campaign related to the great mid-eighteenth-century novel, The Dream of the Red Chamber 紅樓夢 (aka The Story of the Stone 石頭記). But these are topics for another day.

***

Mao’s words resounded with ex cathedra authority. His observations on the White Paper, his analysis of its importance in internal American political machinations at the time, and his rejection of its core arguments on the basis of his own ideological framework of analysis are also important in understanding the China of Xi Jinping. As we have argued elsewhere, to fail to gain a rudimentary understand of Marxism and Marxist-Leninist thinking, to ignore Mao Zedong’s writings and his historical perspective — the collective work of many thinkers, ideologues and Party propagandists — restricts the would-be student of the Chinese world to current affairs or various faddish forms of essentialism. It is for this reason that China Heritage advocates New Sinology 後漢學:

an approach to contemporary China that appreciates the overculture of the dominant Chinese Communist Party and what, through ideology, its policies, the mass media, the education system and its internal and global propaganda efforts the Party promotes as Official China. It also inducts those engaged with China into the particularities of Translated China, that is the versions of China advocated by the Party authorities through their selective approach to and interpretation of the Chinese world, be it in the contemporary context or that of the tradition or the twentieth century.

***

As mentioned above, Mao’s On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship (30 June 1949) is essential background reading to his essays on the White Paper. This, along with his observations on America in ‘Friendship’ or Aggression? “友谊”, 还是侵略?, are also worth reconsidering in light of the anti-liberal campaign pursued by Xi Jinping’s government since late 2012. This on-going, 360-degree ideological and police action has focussed in particular on China’s rights lawyers, ethnic minorities, men and women of conscience, religious groups and various marginal and dispossessed individuals (see, for example, The Five Vermin 五蠹 Threatening China). Xi Jinping’s party-state is the legitimate heir of Mao’s China; its ideology is underpinned by the ideas and actions of Mao and the co-founders of the People’s Republic.

If one presumes to watch China, one should not fail to see this.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

17 January 2018

***

Related Material:

- Watching China Watching, China Heritage, 5 January 2018-

- Paul Cohen, Discovering History in China: American Historical Writing on the Recent Chinese Past, New York: Columbia University Press, 1985

- Dai Qing, 1948: How Peaceful was the Liberation of Beiping?, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 14 (June 2008)

- Qiang Zhai, 1959: Preventing Peaceful Evolution, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 18 (June 2009)

- William A. Rinze, The Failure of the China White Paper, Constructing the Past, vol.11, Issue 1 (2009): 76-84

- Geremie R. Barmé, The Harmonious Evolution of Information, originally published by China Beat, and reprinted in China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 21 (March 2010)

- Yuan Peng 袁鵬, The Five Vermin 五蠹 Threatening China, trans. G.R. Barmé, The China Story, 4 November 2012

- 沈志華, 《大國對抗》 (沈志華冷戰五書), 九州出版社, 2012年

- Xu Jilin and the Third Way, Key Intellectuals, The China Story

- John Pomfret, The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present, New York: Henry Holt & Company, 2016; and, John Pomfret in discussion with Orville Schell and Elizabeth Economy at The Asia Society, 30 November 2016

- Kevin Peraino, A Force so Swift: Mao, Truman, and the Birth of Modern China, 1949, New York: Crown, 2017

As John Pomfret notes in the Prologue to The Beautiful Country and the Middle Kingdom: America and China, 1776 to the Present (2016):

In 1937, the Japanese invasion of China knit China and America closer together than ever. Before the war there had been ten thousand Americans in China; their numbers jumped tenfold in just a few years. But as the war progressed, America came to see its Chinese ally, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, as dictatorial, incompetent and, worst of all, unwilling to fight Japan. As a result, many Americans viewed Chiang’s enemies, the Chinese Communist Party, as the true guerrilla David battling a mechanized Japanese Goliath. State Department officials were convinced of the accuracy of this perspective, and steered US policy away from providing aid to Chiang for his showdown with the Communists after the war.

We now know that the reality was more complex. Chiang’s armies fought so stalwartly that it was they, not the Communists, who sustained 90 percent of the casualties battling the Japanese. Americans at the time comforted themselves with the notion that the United States had done all it could to help Chiang Kai-shek. But countless promises of aid, weapons, and gold to his government had gone unfulfilled.

Some historians have argued that after the war the United States missed a chance to forge good relations with Chairman Mao Zedong as Communism took hold. But documents from Chinese archives released in recent years show that Mao was not ready for ties with America. Mao used hatred of the US as an ideological pillar of his revolution. Even today, the legacy of Mao’s paranoia about America colors China’s relations with the United States.

***

The White Paper

United States Relations with China was published by the US State Department on 5 August 5 1949. Acheson’s Letter of Transmittal to Truman was dated 30 July 1949. The main body of the White Paper, divided into eight chapters, deals with Sino-US relations in the period from 1844, when the United States and the Qing imperial government signed the Treaty of Wanghia 望廈條約, to 1949.

The White Paper goes into particular detail about US policy following the end of the Pacific War in 1945.

***

Sources:

- Publication of China White Paper, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1949, The Far East: China, Vol.IX, Office of the Historian

- China White Paper 1949, 2 vols., Stanford University Press, 1967, full PDF text, introduced by Lyman P. Van Slyke

- Albert C. Wedemeyer, Wedemeyer Reports!, New York: Holt, 1958, especially Appendix VI, ‘Report on China-Korea’, 1947, pp.461ff.

As Qiang Zhai, a historian of the Cold War, writes:

As the CCP approached nationwide triumph, it repeatedly warned its cadres and soldiers against the danger of U.S. intervention. The party leadership believed that the threat from the United States could come either in the form of direct military invasion or by indirect meddling through secret agents, sabotage, and political infiltration. In perceiving this U.S. menace, the CCP leaders were influenced by the existing political context, by their ideological beliefs, and by historical analogies.

In the CCP-KMT struggle for power, the United States sided with Chiang Kai-shek. Ideologically, America was the number-one imperialist power, inherently antagonistic toward national liberation movements and with many imperialist interests and prerogatives in China to protect. Historically, Washington had a tradition of intervention in foreign revolutions. In this regard, the history of U.S. intervention during the Russian Revolution sensitized the CCP leadership to the danger that the Americans might react similarly against them. This point merits close attention when analyzing Chinese Communist perceptions of the U.S. threat.

… CCP leaders tended to use the past to make sense of the present. This exercise often involved dipping into the grab bag of historical experience for instances that offered instructive analogies to current problems. They were prone to envision the future either as foreshadowed by past parallels or as following a straight track from what had recently gone before. Thus, it was both easy and natural for them to apply the Soviet experience to their own situation. They believed that, because Western imperialists had opposed the Bolshevik Revolution, they would not put up with the Chinese Revolution either. Mao claimed: “Make trouble, fail, make trouble again, fail again … till their doom; that is the logic of the imperialists and all reactionaries the world over in dealing with the people’s cause, and they will never go against this logic.” Imperialists never learned from their mistakes, Mao explained; instead, they invariably repeated them.

It is important to point out that CCP leaders’ understanding of Western intervention in the Russian Revolution was both simplistic and inaccurate. For instance, when analyzing the reason for the failure of the Allied mission, Zhou Enlai argued that this was because American soldiers “could not bear hardships.” Zhou was obviously not cognizant of the complex nature of the intervention and had no idea of the lack of official determination and coordination that characterized the entire course of the action.

From their misreading of the American intervention in the Russian Revolution, CCP officials developed another misperception of the United States: American soldiers were spoiled by a rich and comfortable life in a capitalist society […]:

“If American troops really invade China, we will surround them from the countryside, forcing them to ship all military supplies, including toilet paper and ice cream, from the United States. They would be burdened by big cities… . The Americans enjoy a high standard of living and are unwilling to fight. After the Russian October Revolution, the United States once intervened, but the result was “voluntary withdrawal”? Why? This was because they could not bear hardships. We have defeated the Japanese invaders. Are we to be afraid of American troops?”

The result was ironic. Although CCP leaders were conscious of history, they also tended to misapply history. They failed to appreciate not only changes in contexts and actors over time but also variables that changed from one situation to another. Once persuaded that Western intervention in 1918-20 was repeating itself, they tended to see only factors conforming to such an image. When referring to a past lesson, they were inclined to grab the first that came to mind. They did not pause to examine the instance and test its applicability. Merely projecting a trend, they failed to dissect the forces that gave rise to it and to ask if those factors would persist with the same effect.

— Qiang Zhai, The Dragon, the Lion, and the Eagle:

Chinese-British-American Relations, 1949-1958,

Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1994, pp.30-34

Mao Zedong on the United States, 1949

Mao Zedong and his propagandists, in particular Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木 (the Chairman’s chief amanuensis, and frequent co-author), took advantage of the publication of the China White Paper in Washington to launch a nationwide attack on the United States and its relations with China. The day after the publication of the first Communist salvo — ‘A Confession of Helplessness’ 無可奈何的供狀 — written by Hu Qiaomu and revised by Mao, on 12 August 1949, Mao scribbled a note to Hu: ‘take advantage of the White Paper to expose the plots of the imperialists. Excerpted comments from the international media should also be published.’ 應利用白皮書做揭露帝國主義陰謀的宣傳。應將各國評論中摘要評介。

As Lyman Van Slyke notes in his Introduction to the China White Paper, quoted previously:

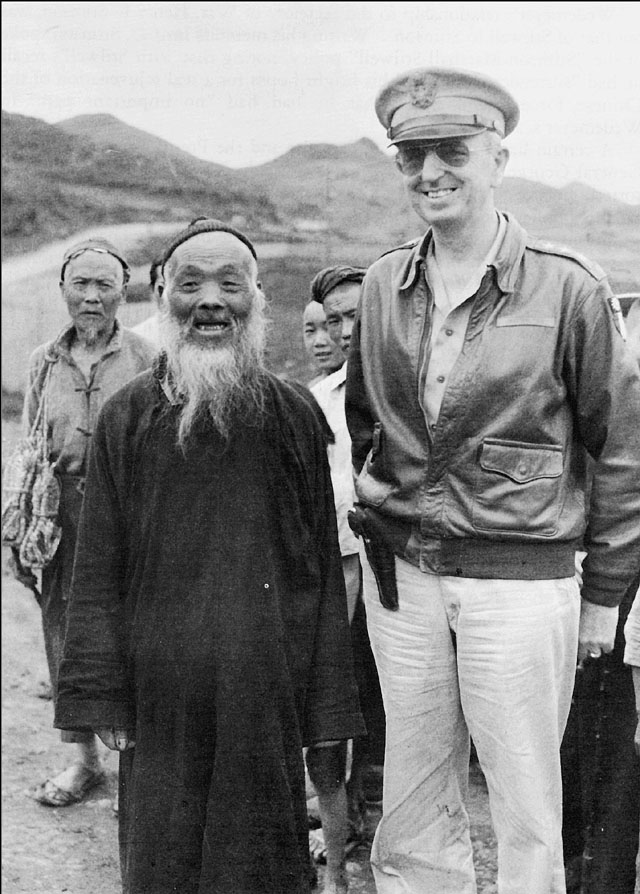

The campaign sought to discredit the United States for everything it had done in China since the Treaty of Wanghia in 1844, and especially for its recent actions. The Chinese Communists did not find it necessary, or desirable, to translate the White Paper. Instead, they concentrated almost entirely on extracts from Acheson’s Letter of Transmittal: the amount of aid given to the Nationalists; the assertion that the United States had done all it could to support Chiang; the claim that the ‘Communist leaders have foresworn their Chinese heritage’ and are subservient to Russia; and above all, the statement that the United States should encourage developments to ‘throw off the foreign yoke.’

In this campaign, John Leighton Stuart, a former president of Yen-ching University, was particularly singled out, both as our last ambassador on the mainland, and also because he represented so well all that was finest in the American philanthropic and educational tradition in China. In ‘Farewell, Leighton Stuart!’ Mao denounced him as one who ‘used to pretend to love both the United States and China.’ The article ends venomously: ‘Leighton Stuart has departed and the White Paper has arrived. Very good. Very good. Both events are worth celebrating.’

***

Sources:

-

- On the People’s Democratic Dictatorship — In Commemoration of the Twenty-eighth Anniversary of the Communist Party of China 論人民民主專政——紀念中國共產黨二十八週年, 30 June 1949

- A Confession of Helplessness — on the U.S. Relations with China White Paper 無可奈何的供狀——評美國關於中國問題的白皮書, 12 August 1949, Xinhua News Agency Editorial, drafted by Hu Qiaomu, revised by Mao

- Cast Away Illusions, Prepare for Struggle 丟掉幻想,準備鬥爭 , 14 August 1949

- Farewell, Leighton Stuart! 别了, 司徒雷登, 18 August 1949

- Why It Is Necessary to Discuss the White Paper 為什麼要討論白皮書?, 28 August 1949

- ‘Friendship’ or Aggression? “友谊”, 还是侵略?, 30 August 1949

- The Bankruptcy of the Idealist Conception of History 唯心歷史觀的破產, 16 September 1949

- 程中原, 對一篇補正文章的補說, 《百年潮》, 2006年第6期

***

Mao Zedong’s Five Critiques of the

US-China White Paper (excerpts with notes)

From ‘Cast Away Illusions, Prepare for Struggle’

All these wars of aggression, together with political, economic and cultural aggression and oppression, have caused the Chinese to hate imperialism, made them stop and think, “What is all this about?” and compelled them to bring their revolutionary spirit into full play and become united through struggle. They fought, failed, fought again, failed again and fought again and accumulated long years of experience, accumulated the experience of hundreds of struggles, great and small, military and political, economic and cultural, with bloodshed and without bloodshed — and only then won today’s basic victory. These are the moral conditions without which the revolution could not be victorious. … …

But imperialism and its running dogs, the reactionary governments of China, could control only a part of these intellectuals and finally only a handful, such as Hu Shi, Fu Sinian and Qian Mu;[Note: Hu Shi, who was formerly a university professor, university president and ambassador of the Kuomintang government to the United States, is a well-known apologist for U.S. imperialism among Chinese bourgeois intellectuals. Fu Sinian and Qian Mu, also university professors, were scholars serving the reactionary Kuomintang government.] all the rest got out of control and turned against them. Students, teachers, professors, technicians, engineers, doctors, scientists, writers, artists and government employees, all are revolting against or parting company with the Kuomintang. The Communist Party is the party of the poor and is described in the Kuomintang’s widespread, all-pervasive propaganda as a band of people who commit murder and arson, who rape and loot, who reject history and culture, renounce the motherland, have no filial piety or respect for teachers and are impervious to all reason, who practice community of property and of women and employ the military tactics of the “human sea” — in short, a horde of fiendish monsters who perpetrate every conceivable crime and are unpardonably wicked. But strangely enough, it is this very horde that has won the support of several hundred million people, including the majority of the intellectuals, and especially the student youth.

Part of the intellectuals still want to wait and see. They think: the Kuomintang is no good and the Communist Party is not necessarily good either, so we had better wait and see. Some support the Communist Party in words, but in their hearts they are waiting to see. They are the very people who have illusions about the United States. They are unwilling to draw a distinction between the U.S. imperialists, who are in power, and the American people, who are not. They are easily duped by the honeyed words of the U.S. imperialists, as though these imperialists would deal with People’s China on the basis of equality and mutual benefit without a stern, long struggle. They still have many reactionary, that is to say, anti-popular, ideas in their heads, but they are not Kuomintang reactionaries. They are the middle-of-the-roaders or the right-wingers in People’s China. They are the supporters of what Acheson calls “democratic individualism”. The deceptive manoeuvres of the Achesons still have a flimsy social base in China. … …

The slogan, “Prepare for struggle”, is addressed to those who still cherish certain illusions about the relations between China and the imperialist countries, especially between China and the United States. With regard to this question, they are still passive, their minds are still not made up, they are still not determined to wage a long struggle against U.S. (and British) imperialism because they still have illusions about the United States. There is still a very wide, or fairly wide, gap between these people and ourselves on this question. … …

The publication of the U.S. White Paper and Acheson’s Letter of Transmittal is worthy of celebration, because it is a bucket of cold water and a loss of face for those who have ideas of the old type of democracy or democratic individualism, who do not approve of, or do not quite approve of, or are dissatisfied with, or are somewhat dissatisfied with, or even resent, people’s democracy, or democratic collectivism, or democratic centralism, or collective heroism, or patriotism based on internationalism — but who still have patriotic feelings and are not Kuomintang reactionaries. It is a bucket of cold water particularly for those who believe that everything American is good and hope that China will model herself on the United States.

Acheson openly declares that the Chinese democratic individualists will be “encouraged” to throw off the so-called “foreign yoke”. That is to say, he calls for the overthrow of Marxism-Leninism and the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the Communist Party of China. For this “ism” and this system, it is alleged, are “foreign”, with no roots in China, imposed on the Chinese by the German, Karl Marx (who died sixty-six years ago), and the Russians, Lenin (who died twenty-five years ago) and Stalin (who is still alive); this “ism” and this system, moreover, are downright bad, because they advocate the class struggle, the overthrow of imperialism, etc.; hence they must be got rid of. In this connection, it is alleged, “the democratic individualism of China will reassert itself” with the “encouragement” of President Truman, the backstage Commander-in-Chief Marshall, Secretary of State Acheson (the charming foreign mandarin responsible for the publication of the White Paper) and Ambassador Leighton Stuart who has scampered off. Acheson and his like think they are giving “encouragement”, but those Chinese democratic individualists who still have patriotic feelings, even though they believe in the United States, may quite possibly feel this is a bucket of cold water thrown on them and a loss of face; for instead of dealing with the authorities of the Chinese people’s democratic dictatorship in the proper way, Acheson and his like are doing this filthy work and, what is more, they have openly published it. What a loss of face! What a loss of face! To those who are patriotic, Acheson’s statement is no “encouragement” but an insult.

China is in the midst of a great revolution. All China is seething with enthusiasm. The conditions are favourable for winning over and uniting with all those who do not have a bitter and deep-seated hatred for the cause of the people’s revolution, even though they have mistaken ideas. Progressives should use the White Paper to persuade all these persons.

***

From ‘Farewell, Leighton Stuart!’

Let those Chinese who believe that “victory is possible even without international help” listen. Acheson is giving you a lesson. Acheson is a good teacher, giving lessons free of charge, and he is telling the whole truth with tireless zeal and great candour. The United States refrained from dispatching large forces to attack China, not because the U.S. government didn’t want to, but because it had worries. First worry: the Chinese people would oppose it, and the U.S. government was afraid of getting hopelessly bogged down in a quagmire. Second worry: the American people would oppose it, and so the U.S. government dared not order mobilization. Third worry: the people of the Soviet Union, of Europe and of the rest of the world would oppose it, and the U.S. government would face universal condemnation. Acheson’s charming candour has its limits and he is unwilling to mention the third worry. The reason is he is afraid of losing face before the Soviet Union, he is afraid that the Marshall Plan in Europe,[Note: On June 5, 1947, U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall made a speech at Harvard University, putting forward a plan for so-called U.S. “aid” to rehabilitate Europe. The “European Recovery Programme” subsequently drawn up by the U.S. government on the basis of the speech was known as the “Marshall Plan”.] which is already a failure despite pretences to the contrary, may end dismally in total collapse.

Let those Chinese who are short-sighted, muddle-headed liberals or democratic individualists listen. Acheson is giving you a lesson; he is a good teacher for you. He has made a clean sweep of your fancied U.S. humanity, justice and virtue. Isn’t that so? Can you find a trace of humanity, justice or virtue in the White Paper or in Acheson’s Letter of Transmittal? … …

We Chinese have backbone. Many who were once liberals or democratic individualists have stood up to the U.S. imperialists and their running dogs, the Kuomintang reactionaries. Wen Yiduo rose to his full height and smote the table, angrily faced the Kuomintang pistols and died rather than submit.[Note: Wen Yiduo (1899-1946), famed Chinese poet, scholar and university professor. In 1943 he began to take an active part in the struggle for democracy out of bitter hatred for the reaction and corruption of the Chiang Kai-shek government. After the War of Resistance Against Japan, he vigorously opposed the Kuomintang’s conspiracy with U.S. imperialism to start civil war against the people. On July 15, 1946, he was assassinated in Kunming by Kuomintang thugs.] Zhu Ziqing, though seriously ill, starved to death rather than accept U.S. “relief food”.[Note: Zhu Ziqing (1898-1948) Chinese man of letters and university professor. After the War of Resistance, he actively supported the student movement against the Chiang Kai-shek regime. In June 1948 he signed a declaration protesting against the revival of Japanese militarism, which was being fostered by the United States, and rejecting “U.S. relief” flour. He was then living in great poverty. He died in Beiping on August 12, 1948, from poverty and illness, but even on his death-bed he enjoined his family not to buy the U.S. flour rationed by the Kuomintang government.] Han Yu of the Tang Dynasty wrote a “Eulogy of Bo Yi”,[Note: Han Yu (768-824) was a famous writer of the Tang Dynasty. “Eulogy of Bo Yi” was a prose piece written by him. Bo Yi, who lived towards the end of the Yin Dynasty, opposed the expedition of King Wu of Zhou against the House of Yin. After the downfall of the House of Yin, he fled to the Shouyang Mountain and starved to death rather than eat of Zhou grain.] praising a man with quite a few “democratic individualist” ideas, who shirked his duty towards the people of his own country, deserted his post and opposed the people’s war of liberation of that time, led by King Wu. He lauded the wrong man. We should write eulogies of Wen Yiduo and Zhu Ziqing who demonstrated the heroic spirit of our nation. … …

There are still some intellectuals and other people in China who have muddled ideas and illusions about the United States. Therefore we should explain things to them, win them over, educate them and unite with them, so they will come over to the side of the people and not fall into the snares set by imperialism. But the prestige of U.S. imperialism among the Chinese people is completely bankrupt, and the White Paper is a record of its bankruptcy. Progressives should make good use of the White Paper to educate the Chinese people.

Leighton Stuart has departed and the White Paper has arrived. Very good. Very good. Both events are worth celebrating.

***

From ‘Why It Is Necessary to Discuss the White Paper’

The White Paper is a counter-revolutionary document which openly demonstrates U.S. imperialist intervention in China. In this respect, imperialism has departed from its normal practice. The great, victorious Chinese revolution has compelled one section or faction of the U.S. imperialist clique to reply to attacks from another by publishing certain authentic data on its own actions against the Chinese people and drawing reactionary conclusions from the data, because otherwise it could not get by. The fact that public revelation has replaced concealment is a sign that imperialism has departed from its normal practice. Until a few weeks ago, before the publication of the White Paper, the governments of the imperialist countries, though they engaged in counter-revolutionary activities every day, had never told the truth in their statements or official documents but had filled or at least flavoured them with professions of humanity, justice and virtue. This is still true of British imperialism, an old hand at trickery and deception, as well as of several other smaller imperialist countries. Opposed by the people on the one hand and by another faction in their own camp on the other, the newly arrived, upstart and neurotic U.S. imperialist group — Truman, Marshall, Acheson, Leighton Stuart and others — have considered it necessary and practicable to reveal publicly some (but not all) of their counter-revolutionary doings in order to argue with opponents in their own camp as to which kind of counter-revolutionary tactics is the more clever. In this way they have tried to convince their opponents so that they can go on applying what they regard as the cleverer counter-revolutionary tactics. Two factions of counter-revolutionaries have been competing with each other. One said, “Ours is the best method.” The other said, “Ours is the best.” When the dispute was at its hottest, one faction suddenly laid its cards on the table and revealed many of its treasured tricks of the past — and there you have the White Paper.

And so the White Paper has become material for the education of the Chinese people. For many years, a number of Chinese (at one time a great number) only half-believed what we Communists said on many questions, mainly on the nature of imperialism and of socialism, and thought, “It may not be so.” This situation has undergone a change since August 5, 1949. For Acheson gave them a lesson and he spoke in his capacity as U.S. Secretary of State. In the case of certain data and conclusions, what he said coincides with what we Communists and other progressives have been saying. Once this happened, people could not but believe us, and many had their eyes opened — “So that’s the way things really were!”

Acheson begins his Letter of Transmittal to Truman with the story of how he compiled the White Paper. His White Paper, he says, is different from all others, it is very objective and very frank:

This is a frank record of an extremely complicated and most unhappy period in the life of a great country to which the United States has long been attached by ties of closest friendship. No available item has been omitted because it contains statements critical of our policy or might be the basis of future criticism. The inherent strength of our system is the responsiveness of the Government to an informed and critical public opinion. It is precisely this informed and critical public opinion which totalitarian governments, whether Rightist or Communist, cannot endure and do not tolerate.

Certain ties do exist between the Chinese people and the American people. Through their joint efforts, these ties may develop in the future to the point of the “closest friendship”. But the obstacles placed by the Chinese and U.S. reactionaries were and still are a great hindrance to these ties. Moreover, because the reactionaries of both countries have told many lies to their peoples and played many filthy tricks, that is, spread much bad propaganda and done many bad deeds, the ties between the two peoples are far from close. What Acheson calls “ties of closest friendship” are those between the reactionaries of the two countries, not between the peoples. Here Acheson is neither objective nor frank, he confuses the relations between the two peoples with those between the reactionaries. … …

To say that a government led by the Communist Party is a “totalitarian government” is also half true. It is a government that exercises dictatorship over domestic and foreign reactionaries and does not give any of them any freedom to carry on their counter-revolutionary activities. Becoming angry, the reactionaries rail: “Totalitarian government!” Indeed, this is absolutely true so far as the power of the people’s government to suppress the reactionaries is concerned. This power is now written into our programme; it will also be written into our constitution. Like food and clothing, this power is something a victorious people cannot do without even for a moment. It is an excellent thing, a protective talisman, an heirloom, which should under no circumstances be discarded before the thorough and total abolition of imperialism abroad and of classes within the country. The more the reactionaries rail “totalitarian government”, the more obviously is it a treasure. But Acheson’s remark is also half false. For the masses of the people, a government of the people’s democratic dictatorship led by the Communist Party is not dictatorial or autocratic but democratic. It is the people’s own government. The working personnel of this government must respectfully heed the voice of the people. At the same time, they are teachers of the people, teaching the people by the method of self-education or self-criticism.

***

From ‘Friendship’ or Aggression?

Seeking to justify aggression, Dean Acheson harps on “friendship” and throws in lots of “principles”.

Acheson says:

The interest of the people and the Government of the United States in China goes far back into our history. Despite the distance and broad differences in background which separate China and the United States, our friendship for that country has always been intensified by the religious, philanthropic and cultural ties which have united the two peoples, and has been attested by many acts of good will over a period of many years, including the use of the Boxer indemnity for the education of Chinese students, the abolition of extraterritoriality during the Second World War, and our extensive aid to China during and since the close of the War. The record shows that the United States has consistently maintained and still maintains those fundamental principles of our foreign policy toward China which include the doctrine of the Open Door, respect for the administrative and territorial integrity of China, and opposition to any foreign domination of China.

Acheson is telling a bare-faced lie when he describes aggression as “friendship”.

The history of the aggression against China by U.S. imperialism, from 1840 when it helped the British in the Opium War to the time it was thrown out of China by the Chinese people, should be written into a concise textbook for the education of Chinese youth.

The United States was one of the first countries to force China to cede extraterritoriality [Note: “Extraterritoriality” here refers to consular jurisdiction. It was one of the special privileges for aggression which the imperialists wrested from China. Under the so-called consular jurisdiction, nationals of imperialist countries residing in China were not subject to the jurisdiction of Chinese law; when they committed crimes or became defendants in civil lawsuits, they could be tried only in their respective countries’ consular courts in China, and the Chinese government could not intervene.] — witness the Treaty of Wanghia [Note: The “Treaty of Wanghia” was the first unequal treaty signed as a result of U.S. aggression against China. The United States, taking advantage of China’s defeat in the Opium War, compelled the Qing Dynasty to sign this treaty, also called the “Sino-American Treaty on the Opening of Five Ports for Trade”, in Wanghia Village near Macao in July 1844. Its thirty-four articles stipulated that whatever rights and privileges, including consular jurisdiction, were gained by Britain through the Treaty of Nanking and its annexes would also accrue to the United States.] of 1844, the first treaty ever signed between China and the United States, a treaty to which the White Paper refers. In this very treaty, the United States compelled China to accept American missionary activity, in addition to imposing such terms as the opening of five ports for trade. For a very long period, U.S. imperialism laid greater stress than other imperialist countries on activities in the sphere of spiritual aggression, extending from religious to “philanthropic” and cultural undertakings. According to certain statistics, the investments of U.S. missionary and “philanthropic” organizations in China totalled 41,900,000 U.S. dollars, and 14.7 per cent of the assets of the missionary organizations were in medical service, 38.2 per cent in education and 47.1 per cent in religious activities. Many well-known educational institutions in China, such as Yenching University, Peking Union Medical College, the Huei Wen Academies, St. John’s University, the University of Nanking, Soochow University, Hangchow Christian College, Hsiangya Medical School, West China Union University and Lingnan University, were established by Americans. It was in this field that Leighton Stuart made a name for himself; that was how he became U.S. ambassador to China. Acheson and his like know what they are talking about, and there is a background for his statement that “our friendship for that country has always been intensified by the religious, philanthropic and cultural ties which have united the two peoples”. It was all for the sake of “intensifying friendship”, we are told, that the United States worked so hard and deliberately at running these undertakings for 105 years after the signing of the Treaty of 1844.

Participation in the Eight-Power Allied Expedition to defeat China in 1900, the extortion of the “Boxer Indemnity” and the later use of this fund “for the education of Chinese students” for purposes of spiritual aggression — this too counts as an expression of “friendship”.

Despite the “abolition” of extraterritoriality, the culprit in the raping of Shen Chung was declared not guilty and released by the U.S. Navy Department on his return to the United States — this counts as another expression of “friendship”.

“Aid to China during and since the close of the War”, totalling over 4,500 million U.S. dollars according to the White Paper, but over 5,914 million U.S. dollars according to our computation, was given to help Chiang Kai-shek slaughter several million Chinese — this counts as yet another expression of “friendship”.

All the “friendship” shown to China by U.S. imperialism over the past 109 years (since 1840 when the United States collaborated with Britain in the Opium War), and especially the great act of “friendship” in helping Chiang Kai-shek slaughter several million Chinese in the last few years — all this had one purpose, namely, it “consistently maintained and still maintains those fundamental principles of our foreign policy toward China which include the doctrine of the Open Door, respect for the administrative and territorial integrity of China, and opposition to any foreign domination of China”.

Several million Chinese were killed for no other purpose than first, to maintain the Open Door, second, to respect the administrative and territorial integrity of China and, third, to oppose any foreign domination of China.

***

From ‘The Bankruptcy of the Idealist Conception of History’

The Chinese should thank Acheson, spokesman of the U.S. bourgeoisie, not merely because he has explicitly confessed to the fact that the United States supplied the money and guns and Chiang Kai-shek the men to fight for the United States and slaughter the Chinese people and because he has thus given Chinese progressives evidence with which to convince the backward elements. You see, hasn’t Acheson himself confessed that the great, sanguinary war of the last few years, which cost the lives of millions of Chinese, was planned and organized by U.S. imperialism? The Chinese should thank Acheson, again not merely because he has openly declared that the United States intends to recruit the so-called “democratic individualists” in China, organize a U.S. fifth column and overthrow the People’s Government led by the Communist Party of China and has thus alerted the Chinese, especially those tinged with liberalism, who are promising each other not to be taken in by the Americans and are all on guard against the underhand intrigues of U.S. imperialism. The Chinese should thank Acheson also because he has fabricated wild tales about modern Chinese history; and his conception of history is precisely that shared by a section of the Chinese intellectuals, namely, the bourgeois idealist conception of history. … …

For a long time in the course of this resistance movement, that is, for over seventy years from the Opium War of 1840 to the eve of the May 4th Movement of 1919, the Chinese had no ideological weapon with which to defend themselves against imperialism. The ideological weapons of the old die-hard feudalism were defeated, had to give way and were declared bankrupt. Having no other choice, the Chinese were compelled to arm themselves with such ideological weapons and political formulas as the theory of evolution, the theory of natural rights and of the bourgeois republic, which were all borrowed from the arsenal of the revolutionary period of the bourgeoisie in the West, the native home of imperialism. The Chinese organized political parties and made revolutions, believing that they could thus resist foreign powers and build a republic. However, all these ideological weapons, like those of feudalism, proved very feeble and in their turn had to give way and were withdrawn and declared bankrupt.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 awakened the Chinese, and they learned something new, Marxism-Leninism. In China, the Communist Party was born, an epoch-making event. Sun Yat-sen, too, advocated “learning from Russia” and “alliance with Russia and the Communist Party”. In a word, from that time China changed her orientation. … …

The reason why Marxism-Leninism has played such a great role in China since its introduction is that China’s social conditions call for it, that it has been linked with the actual practice of the Chinese people’s revolution and that the Chinese people have grasped it. Any ideology — even the very best, even Marxism-Leninism itself — is ineffective unless it is linked with objective realities, meets objectively existing needs and has been grasped by the masses of the people. We are historical materialists, opposed to historical idealism. … …

Since they learned Marxism-Leninism, the Chinese people have ceased to be passive in spirit and gained the initiative. The period of modern world history in which the Chinese and Chinese culture were looked down upon should have ended from that moment. The great, victorious Chinese People’s War of Liberation and the great people’s revolution have rejuvenated and are rejuvenating the great culture of the Chinese people. In its spiritual aspect, this culture of the Chinese people already stands higher than any in the capitalist world. Take U.S. Secretary of State Acheson and his like, for instance. The level of their understanding of modern China and of the modern world is lower than that of an ordinary soldier of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army.

Up to this point, Acheson, like a bourgeois professor lecturing on a tedious text, has pretended to trace the causes and effects of events in China. Revolution occurred in China, first, because of over-population and, second, because of the stimulus of Western ideas. You see, he appears to be a champion of the theory of causation. But in what follows, even this bit of tedious and phoney theory of causation disappears, and one finds only a mass of inexplicable events. Quite unaccountably, the Chinese fought among themselves for power and money, suspecting and hating each other. An inexplicable change took place in the relative moral strength of the two contending parties, the Kuomintang and the Communist Party; the morale of one party dropped sharply to below zero, while that of the other rose sharply to white heat. What was the reason? Nobody knows. Such is the logic inherent in the “high order of culture” of the United States as represented by Dean Acheson.

Note:

These English translations, and notes, are taken from the official Selected Works of Mao Tse-tung, vols I-IV, Peking: Foreign Languages Press, 1961. The transliteration of Chinese names has, for the most part, been changed to Hanyu pinyin.

Nixon Agonistes

It would be nearly two decades before Richard Nixon published his own insights on China, a prelude to his momentous 1972 trip to Beijing:

Taking the long view, we simply cannot afford to leave China forever outside the family of nations, there to nurture its fantasies, cherish its hates and threaten its neighbors. There is no place on this small planet for a billion of its potentially most able people to live in angry isolation.

The world cannot be safe until China changes. Thus our aim, to the extent that we can influence events, should be to induce change. They way to do this is to persuade China that it must change: that it cannot satisfy its imperial ambitions, and that its own national interest requires a turning away from foreign adventuring and a turning inward toward the solution of its own domestic problems.

— Richard M. Nixon, Asia after Viet Nam,

Foreign Affairs, vol.46 (October 1967): 121

***

Acheson’s Global View

It seems to me inevitable that we are going to live on this globe with a vast number of people who think as oppositely as we do as it is possible for human beings to think.

We must understand that for a long, long period of time we will both inhabit this spinning ball in the great void of the universe.

— Dean Acheson,

‘Remarks at the National War College’, 21 December 1949,

quoted in Kevin Peraino, A Force so Swift: Mao, Truman,

and the Birth of Modern China, 1949, 2017, p.248