The Other China

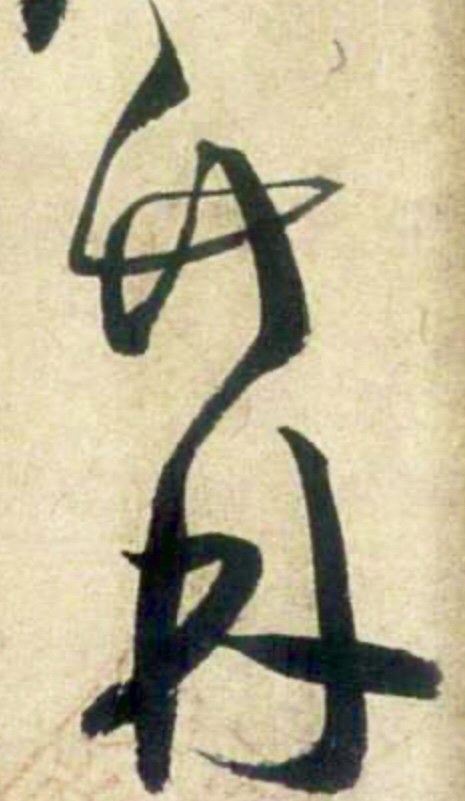

引清風

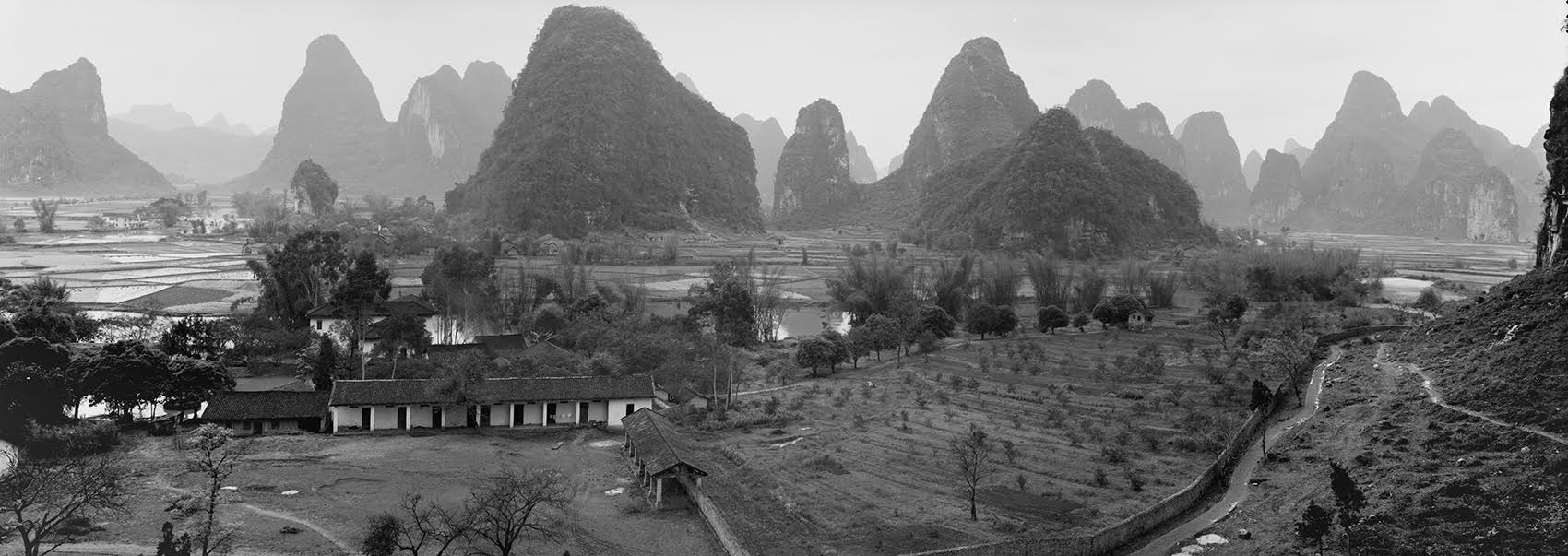

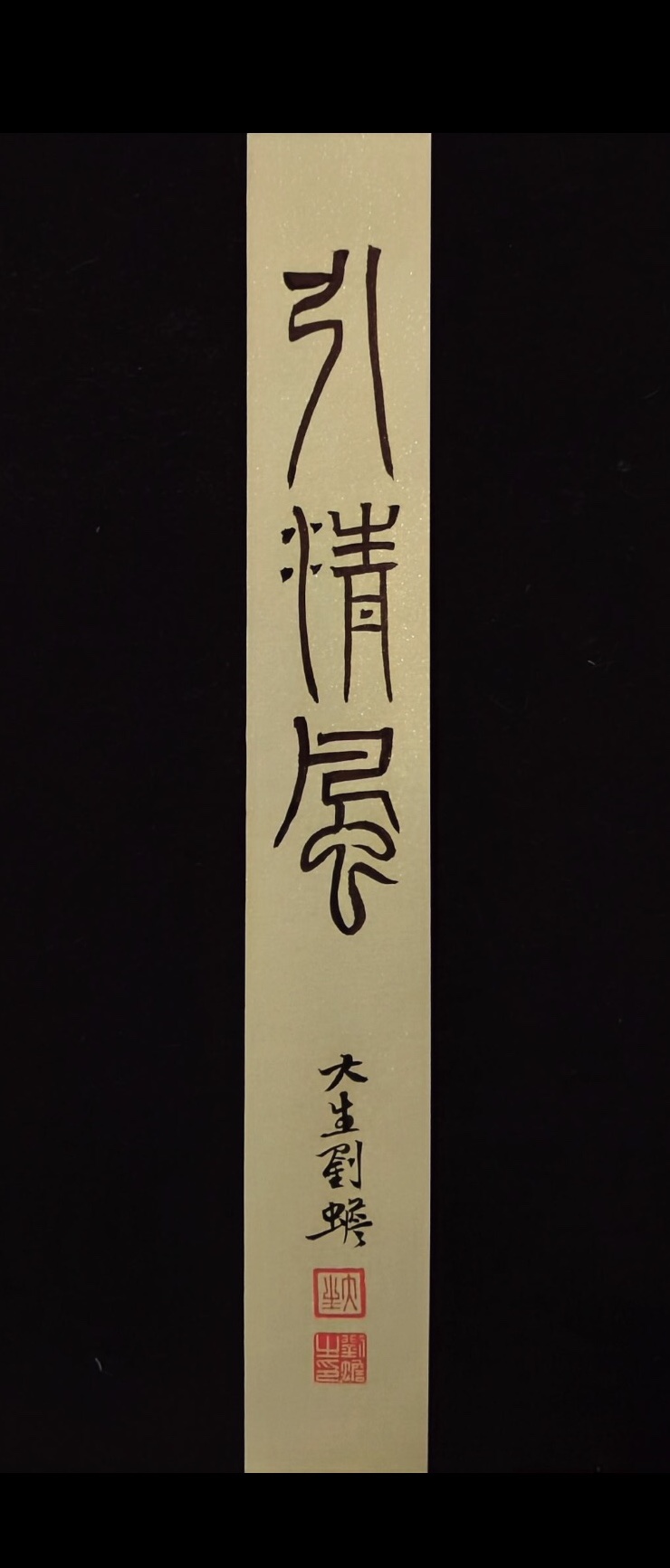

The following celebration of bamboo is inspired by the calligraphy of Liu Chan 劉蟾 and features the scholarship of Duncan Campbell as well as the art of Lois Conner.

We are grateful to Duncan for permission to quote liberally from his important study of bamboo in the Chinese garden and to Lois for allowing us to use her work.

***

***

The title of this chapter in The Other China — ‘When Bamboo Invites a Zeyphr’ — is a reference to Zheng Xie (鄭燮 1693-1765), a Qing-dynasty artist also known as Zheng Banqiao 鄭板橋, who declared that ‘rocks evoke soaring crags just as bamboos entice a zephyr [or, invite a gentle breeze]’ 竹引清風, 石存岳意. For more on Zheng’s celebrated obsession with bamboo, see below.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

12 May 2023

***

Related Material:

- Liu Chan, in The Other China

- Duncan Campbell Archive

- Lois Conner, website

An Invitation to the Breeze

Duncan M. Campbell

***

In the Studio of the Green Culm

綠筠軒

Su Shi 蘇軾

可使食無肉

不可居無竹

無肉令人瘦

無竹令人俗

人瘦尚可肥

俗士不可醫

Whereas one may eat a meal without meat,

One cannot live at a place without bamboo.

Without meat, one grows thin,

Without bamboo, one becomes vulgar.

A thin man may yet become fat,

A vulgar man is quite beyond cure.

— Su Shi, ‘Studio of the Green Culm of the Monk of Yuqian’

於潛僧綠筠軒

***

… The most authoritative discussion of the art of painting bamboo, that conducted between Su Shi 蘇軾 (Dongpo 東坡; 1037-1101) and his distant older cousin Wen Tong (文同, Yuke 輿可; 1019-1079).

Wen Tong’s paintings and calligraphy bulked large in the art collection that Su Shi gathered around him, and in his account of Wen Tong’s studio, ‘Record of the Hall of the Ink Gentleman’ 墨君堂記, Su Shi says of him that although everyone under heaven calls the bamboo worthy, ‘Only Yuke truly knows this gentleman in a profound way, understands why it is that he is worthy’ 然與可獨能得君之深而知君之所以賢.

The conversation between the two men about ink bamboo or mòzhú 墨竹 (conducted by means of ‘Poems on Paintings’, colophons, essays and so on) lasted almost thirty years, having continued long after the older man’s death whenever Su Shi had occasion to view an ink bamboo by him.

To Su Shi’s mind, Wen Tong and his bamboos became indistinguishable, the one from the other, particularly in terms of their moral character. Su captures this understanding in the first of a set of poems entitled ‘Three Poems Written on the Painting of Bamboo by Yuke Owned by Chao Buzhi’ 書晁補之所藏與可畫竹三首:

與可畫竹時

見竹不見人

豈獨不見人

其身與竹化

無窮出清新

莊周世無有

誰知此凝神

Whenever Yuke paints a bamboo,

He sees the bamboo but never himself.

Not only does he never see himself,

His body and the bamboo merge into one,

Producing an endless array of pure newness.

This age of ours is without its Master Zhuang,

And so who now understands this level of afflatus?

In the most famous written record of the exchange between Su Shi and Wen Tong on the topic of the painting of bamboo — ‘Record of Wen Tong’s Painting of the Bent Bamboos of the Valley of the Tall Bamboos’ 文與可畫篔簹谷偃竹記 — Su Shi argues that ‘Anyone painting bamboo must have a completed bamboo already in his chest’ 故畫竹必先得成竹於胸中 before they take up the brush.

***

***

The Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove

竹林七賢

Ruan Ji of Chenliu, Xi Kang of the Principality of Jiao, and Shan Tao of Henei were all about the same age, with Xi Kang being the youngest of the three. Joining them later on were Liu Ling of the Principality of Pei, Ruan Xian of Chenliu, Xiang Xiu of Henei, and Wang Rong of Langye. The seven of them would frequently gather within a bamboo grove, there to drink and carouse to their heart’s content. And so it was that contemporaries labelled them the ‘Seven Worthies of the Bamboo Grove’.

陳留阮籍譙國嵇康河內山濤三人年皆相比康年少亞預此契者沛國劉伶陳留阮咸河內向秀琅耶王戎七人常集於竹林之下肆意酣暢故世謂竹林七賢

— Liu Yiqing (劉義慶, 403-444 CE), A New Account of Tales of the World, 5

劉義慶,《世說新語·任誕》

***

***

The Chinese Life of Bamboo

China is home to some 620 varieties of bamboo — zhú 竹 in Standard Chinese; Bambuseae — more than half of the varieties that have so far been identified, and the bamboo bulks large in the vegetative matter of most Chinese gardens, as it does also in the poems, paintings, and essays produced in those gardens. Very frequently, the bamboo features in the names of the gardens, and in the names of the structures or scenes within those gardens.

‘Nothing could be more deeply characteristic of the Chinese scene than they,’ Joseph Needham claims in his discussion of Dai Kaizhi’s monograph on the plant, ‘or more prominent in Chinese art and technology through the ages.’

‘Bamboo is an essential component of any Chinese garden,’ Peter Valder argues: as fence or railing 竹籬 zhú lí or bali 笆籬 bā lí or trellis 竹屏 zhú píng bamboo serves to divide and to screen, as poles they provide the scaffolding for the structures of the garden, when worked, they serve to supply the tools of the garden (rakes and brooms, stakes, rainhats, walking sticks, fishing poles, fish traps, baskets, bridges, and so on), the tools of the study and bedroom (brushes, brush pots and holders, wrist rests, fans, blinds, various items of furniture and types of musical instrument, floor mats, book trunks, bookmarks or index-labels, bamboo (or Dutch) wives 竹夫人 zhú fūrén, paper, combs, and both the tools of the kitchen (chopsticks, steamers, sieves, hampers, kindling and charcoal) and a vital ingredient of Chinese cuisine.

The Qing dynasty connoisseur Li Yu (李漁, 1610-1680), for instance, declared bamboo shoots to be ‘the best of all the vegetables’ 蔬食第一品也.

The Chinese engagement with the bamboo down through the ages has also been a profoundly intellectual and emotional one; the bamboo plays a vital role in the powerful but restricted and highly moralised plant-based symbolic language and its associated iconography that the gardens of China sought to embody, what Jonathan Hay calls the ‘…established iconography of moral achievement in the form of imagery of plants, flowers, fruit, and vegetables.’

Like bamboo buffeted by the wind, in the face of powerful adversaries the gentleman may bend but he does not break; his modesty can be likened to the bamboo’s hollow heart 虛心 xū xīn, his integrity to its joints 節 jié, and his humility to the fact that the leaves of the bamboo droop downwards as if bowing in respect. In association with the pine 松 sōng and the prunus mume or flowering apricot 梅 méi, bamboo’s steadfastness in the face of adversity saw it labelled, in poetry, since the Tang dynasty, and depicted in painting since the Song, as one of the ‘Three Friends of the Winter’ 歲寒三友 suì hán sān yǒu.

Somewhat more prosaically, either placed in a vase alongside or depicted together with a spring of flowering apricot, the bamboo symbolised a husband and wife. For traditionally educated Chinese, these understandings of the moral and aesthetic properties of the bamboo, either simply present in a garden as a component of its plantings, or explicitly conjured up by means of name or quotation, serve as a form of mental or remembered paratext that lends meaning to whatever garden it is that they might find themselves within.

***

Bamboo Garden, Beijing

Bamboo Garden 竹園 in Peking, once owned by the prominent Ming official Zhou Jing (周經, 1440-1510), is an example. A party held in this garden in 1499, on the occasion of Zhou’s sixtieth birthday and at which he was joined by nine equally prominent friends, was immortalised in a series of woodblock illustrations of the event produced by the calligrapher Wu Kuan (吳寬, 1436-1504) and entitled ‘Scenes of a Birthday Gathering in Bamboo Garden’ 竹園壽集圖, with the birds drawn by Lü Ji 呂紀 and the human figures by Lü Wenying 呂文英. This title was later reproduced in the 1560s under the title Gatherings in Two Gardens 二園集, a copy of which is held in the Library on Congress, Washington D.C. and an electronic version of which is available online at the World Digital Library.

The Bamboo Garden Hotel in present-day Peking, not far from the Drum Tower 鼓樓, was said to have once belonged to the important late-Qing dynasty reformer Sheng Xuanhuai (盛宣懷, 1844-1916); later on, during the Cultural Revolution (c.1966-1976), it became the residence of Kang Sheng (康生, 1898-1975), sometime chief of internal Communist Party intelligence and security and a man who, over the course of his post-49 career, amassed (for the most part through appropriation) an extraordinary collection of paintings, calligraphy, and antiques, especially inkstones. He was posthumously disgraced.

***

‘Just as I love bamboos and stone, they, too, love me…’

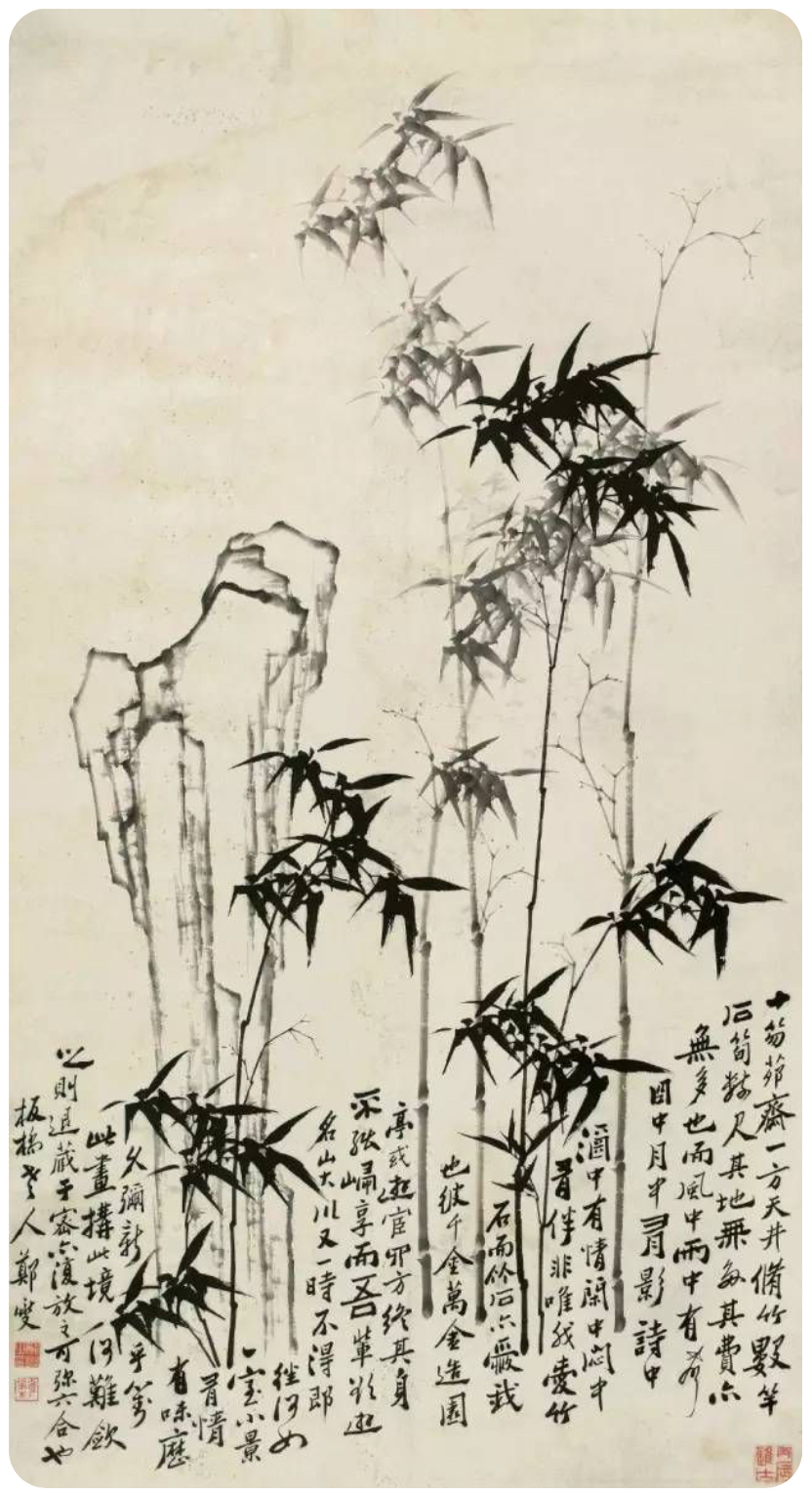

Zheng Xie (鄭燮 1693-1765), better known by his sobriquet Zheng Banqiao 鄭板橋 … appears to have been afflicted by a particular obsession for the plant. The colophon he added to a painting entitled ‘Bamboo and Rock’ 竹石圖, executed in the very last year of his life, provides the following inventory of the sensory dimensions of the bamboo’s ubiquitous presence in the gardens of China.

A thatched studio just ten-hu-wide; a single square Heaven’s Well courtyard. A tall bamboo or two; a solitary stone bamboo shoot some several chi high. A spot not large; nor an expenditure too great. But here it is that music is to be heard whenever a zephyr gets up or the rain begins to fall; shadows dance under the light of either passing sun or rising moon; passions surge when waxing lyrical or in one’s cups; and a companion is forever to be found, whether one is idle or in a funk.

This is not just a case of me loving the bamboo and the rocks, for they too, for their part, love me.

Men there are who spend tens of thousands on building a fine garden, only to find that, travelling here and there on official business, they die without ever having been able to return home to enjoy its delights. For men such as myself who, by contrast, can only dream of visiting the famous mountains and great rivers if at all then very infrequently, what is better than a single room with a miniature vista, replete with emotion and with taste and which, over the passage of time, will constantly renew itself? Facing this scene, and having crafted such a realm, no difficulty is to be encountered when one either ‘rolls it up and withdraws into it in order to hide away in mysteriousness,’ or ‘unrolls it and thus extends oneself throughout the Six Realms of Heaven and Earth and all Four Quarters.’

— Fourth Month of the Yiyou Year (1765) of the reign of the Qianlong emperor, painted by Zheng Xie (Banqiao)

十笏茅齋一方天井修竹數竿石筍數尺其地無多其費亦無多也而風中雨中有聲日中月中有影詩中酒中有情閒中悶中有伴非唯我愛竹石即竹石亦愛我也彼千金萬金造園亭或遊宦四方終其身不能歸享而吾輩欲遊名山大川又一時不得即往何如一室小景有情有味歷久彌新乎對此畫構此境何難斂之則退藏於密亦復放之可彌六合也乾隆乙酉清和月板橋鄭燮畫 …

In another colophon, Zheng Banqiao details his method as a painter of bamboo.

My home includes a two-bayed thatched studio, to the south of which I had bamboos planted. When the first thickets of the summer months begin to cast their green shadow, I have a small bed placed in the studio, affording me the most pleasing manner of staying cool. During the autumn and winter, I have a bamboo trellis built surrounding the studio, but leaving the two ends of the trellis empty, into which space I install horizontal window frames. These frames are then papered over evenly with thin, pure white paper. As the room heats up, as a result of the gentle zephyr and the warm sun, the freezing flies beat drum-like on the paper windows as they try to make their way inside. Every now and then, I catch sight of the disorderly shadow cast by a branch or other of the bamboo, this approximating in my mind, surely, a ‘Natural Painting’. Whenever I paint bamboo, I follow no master, but obtain my images from their shadows cast on my whitewashed walls or paper windows in the light of the day or under the rays of the moon

余家有茅屋二間南面種竹夏日新篁初放綠陰照人置一小榻其中甚涼適也秋冬之際取圍屏骨子斷去兩頭橫安以為窗櫺用勻薄潔白之紙糊之風和日暖凍蠅觸窗紙上冬冬作小鼓聲於時一片竹影零亂豈非天然畫乎凡吾畫竹無所師承多得於紙窗粉壁日光月影中耳

***

Source:

- Duncan M. Campbell, Bamboo in the Chinese Garden, New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 23, 1 (June 2021): 37-52

***

***

On one occasion, when Wang Huizhi 王徽之 was housesitting another man’s house, he ordered that bamboos be planted. Someone taxed him on the effort:

‘Since you’re only to be living here for a short while, why bother having bamboos planted?’

Wang whistled away and chanted poems for a good while; then, abruptly, pointing to the bamboos, he replied,

‘How could I possibly live a single day without these gentlemen?’

王子猷嘗暫寄人空宅住便令種竹或問暫住何煩爾

王嘯詠良久直指竹曰何可一日無此君

— Liu Yiqing, A New Account of Tales of the World, 5

劉義慶,《世說新語·任誕》