千里共嬋娟

The Fifteenth Day of the Eighth Month of the lunar calendar, a day that in 2017 falls on the 4th of October, marks the Mid-Autumn Festival 中秋節. A major public holiday in the People’s Republic since 2008, it is also known as 團圓節, the Festival of Reunions, a celebration of unity, togetherness, familial harmony and even conjugal felicity. In recent years the day is promoted as a ‘second Chinese Valentine’s’. Reunions were so rare and hard won in both China’s dynastic and modern eras that it is hardly surprising they are marked so frequently in the calendar.

In 2017, Mid-Autumn Festival falls within days of the 1st of October National Day (and less than a week before the 10th of October celebration of the founding of the Republic of China on the other side of the Taiwan Strait). As a result, in the People’s Republic there is an eight-day public holiday from Sunday the 1st of October until the following Sunday, the 8th. For more on this, see 1 October 2017 — The Best China.

This is latest in our series of New Sinology Jottings 後漢學劄記. We mark this autumnal festival with a famous poem by Su Dongpo of the Song-dynasty, translated by John Minford, followed by another excerpt from the Hong Kong writer Xi Xi’s Teddy Bear Chronicles 縫熊志, translated by Christina Sanderson. Zhang Dai 張岱, essayist and memorialist of the late Ming-early Qing period in the seventeenth century, recorded revelries on the Full Moon night of the Eighth Month, here we offer one account from Suzhou.

A number of chapters in the great Qing-era novel The Story of the Stone (石頭記, also known as The Dream of the Red Chamber 紅樓夢) also feature the Mid-Autumn Festival, and we have selected an episode from Chapter 1, translated by David Hawkes, to mark this day. This is followed by an account from Six Records of the Fleeting World 浮生六記, a chapter from the Manchu Bannerman Lincing’s memoirs and a famous poem by Mao Zedong in which he mourns a long-dead wife and the flight of Chang’e 嫦娥 to the moon followed by a comment on the political denouement of his last wife, Jiang Qing, and Shanghai hairy crabs. We conclude our reflections on the Harvest Festival by discussing a popular saying and an admonition from China’s party-pooper-in-chief, Xi Jinping: by all means celebrate, but not too much, not for too long and not too lavishly.

***

Our thanks to Christina Sanderson and Annie Ren for their continued contributions to our New Sinology record of Chinese festivities, and to John Minford for his translation of a poem by Su Dongpo, as well as for permission to quote from David Hawkes’ translation of The Story of the Stone.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

Fifteenth Day of the Eighth Month of the

Dingyou Year of the Rooster 2017

丁酉雞年八月十五日中秋節

Su Dongpo

Mid-Autumn,

I stayed up till dawn drinking,

and wrote this thinking of my brother

To the tune ‘Water Song’

When did such a bright moon ever shine?

Raising my goblet, I question the dark firmament:

What year is it tonight

in the Bright Palace of Heaven?

How I wish I could return home to the moon,

That I could ride the wind there,

but I fear that the cold,

high in those jade towers, in that crystal world,

might be too intense to bear.

So I’ll dance here instead

down in the mortal world,

I’ll play with my bright moonlit shadow.

Here it comes again,

moving round the vermilion mansion,

shining through the fretted casement,

in on the sleepless.

What right does it have

to be so cruel?

What right to choose

To shine so full,

So bright,

when we’re so far apart?

Mankind has its

Sorrows and joys,

Meetings and partings.

The moon waxes and wanes

in clear or cloudy skies.

Things were ever imperfect.

May we all live long,

May we all share,

though a myriad miles apart,

the same fair moon.

蘇東坡

辰中秋,

歡飲達旦,大醉。

作此篇,兼懷子由

水調歌頭

明月幾時有,

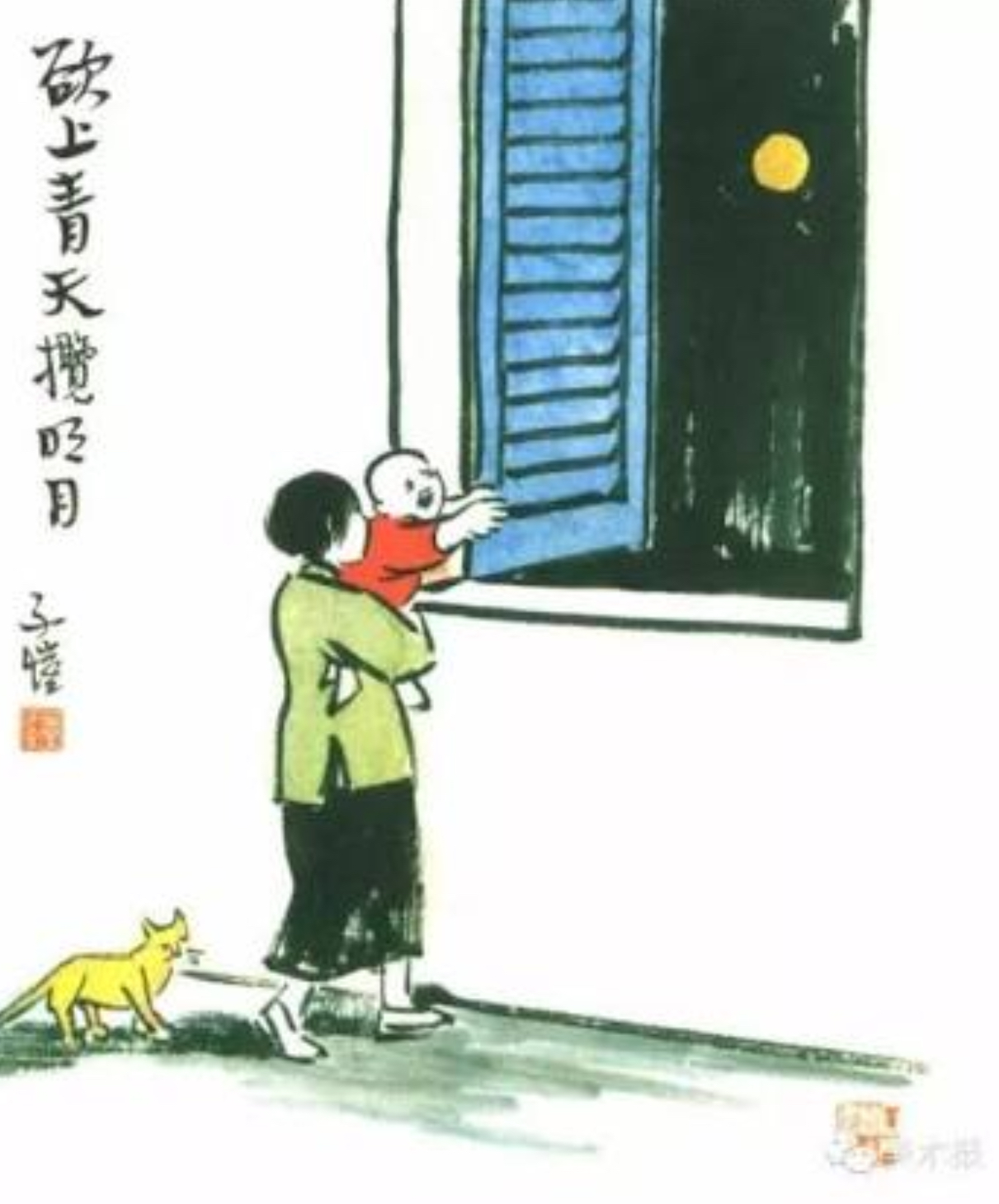

把酒問青天。

不知天上宮闕,

今夕是何年。

我欲乘風歸去,

又恐瓊樓玉宇,

高處不勝寒。

起舞弄清影,

何似在人間。

轉朱閣,

低綺戶,

照無眠。

不應有恨,

何事長向別時圓。

人有悲歡離合,

月有陰晴圓缺,

此事古難全。

但願人長久,

千里共嬋娟。

— translated by John Minford

***

The Queen Mother of the West,

Yi the Archer and Chang’e

西王母、后羿、嫦娥

Xi Xi

Translated by Christina Sanderson, from The Teddy Bear Chronicles

The Queen Mother of the West is a legendary figure in Chinese mythology. She lives in the Kunlun Mountains and was visited there by King Mu of the Zhou Kingdom. Famous peaches of longevity grow in her garden. It’s said they ripen only once in 3000 years and can bestow immortality on those who eat them. Later tradition speaks of her having a husband: Royal Lord of the East.

Hou Yi, or simply Yi, is the famed heroic archer who rescued humanity from annihilation by shooting down nine (or, according to some sources, ten) extra suns which appeared together scorching the earth. As a reward he received the elixir of immortality from the Queen Mother of the West, but his wife, Chang’e, stole it and fled to the moon. She become the spirit of the moon. from the Legendary Past (c. 2100-c. 1600 B.C.)

— Christina Sanderson

based on Herbert Giles,

A Chinese Biographical Dictionary; and,

Yang Lihui and An Deming,

Handbook of Chinese Mythology.

According to the ancient Classic of Maintains and Seas, The Queen Mother of the West is a half-goddess, half-beast mountain sprite dwelling in the Kunlun Mountains, with tiger teeth and a leopard tail, who could issue a sound like a long whistle. That’s how the Queen Mother of the West was depicted in the Warring States period. Famous writers like Qu Yuan, Zhuangzi and Xunzi all mention her. Xunzi went so far as to claim that she was the teacher of Yu the Great. By the Han dynasty she was transformed into a beauty with an impressive entourage. Texts from that time claimed that she met King Mu of the Kingdom of Zhou at Magical Jasper Lake, where they sang ritual songs to one another. By the Wei, Jin and the Six dynasties, she had taken on aspects of Taoist immortality. 《山海經》中的西王母,住在崑崙山,是個半神半獸的山精,長著老虎牙齒,豹子尾巴,很會長嘯。這是戰國時西王母的形象。屈原、莊子、荀子都提過她,荀子還說她是夏禹的老師。到了漢代,則化身美女,有些排場,還和周穆王相會於瑤池,互相唱和。最後,魏晋南北朝時,又加添了道教長生不老的色彩。

The Queen Mother of the West is famous and venerated because she is the goddess in charge of the elixir of life. Stone relief images found in Han-dynasty tombs show her with immortal Taoist priests, and a special rabbit, a creature that helped her pound up the elixir. She had two other capable followers: a three-legged bird and a nine-tailed fox. Despite the many changes to depictions of the Queen Mother over the centuries she was always easily identified by one the distinctive crown she wears. The crown came to symbolise her divine authority. Later, it became a fashion accessory for ordinary girls. It is round in the middle, with two triangles placed above and below the circle, that point in towards each another. A pair of these is set suspended at either end of a horizontal rod, which together make a complete crown. There are gold, silver, jade, silk and coloured paper crowns, as well as brocade and floral designs. On Humanity Day 人日, when human beings were said to have been created, celebrated on the seventh day of the first month during the Six Dynasties, floral crowns were exchanged as lucky talismans. The crown I fashioned for the Queen Mother of the West is a pearl variation. She is wearing a short-sleeve coat over her robe. 西王母所以出名,受人敬畏,因為她掌管了不死藥。在漢代畫像磚的圖中,她身邊除了羽人,就有搗藥的免子。她還有兩個得力的隨從,一是三足烏,一是九尾狐。她的形象,無論怎樣轉變,有一樣東西是少不了的,很易辨認;因為頭上戴勝杖。「勝」,是西王母神權的象徵。「勝」後來發展成為女子的頭飾,形狀是中間圓形,上下是相對的三角形。用一支橫杆擔起一對勝,就成勝杖。勝有金、銀、玉、絲綢、彩紙等材料,也有錦勝,華勝等。六朝時,每到人日(正月七日),大家互贈華勝,作為祝福。我做給西王母的,是珠勝。她穿衣和裙,外罩半臂。

The Han-dynasty clothes and accessories of the Queen Mother of the West reflected the fashion of that time. Classical Chinese clothing stems from two main traditions: one involves a two-piece set made up of a shirt and a skirt that first appeared in the Shang and Zhou eras. It later developed into a two-piece set comprising a short jacket with a long robe underneath. The other main tradition stemmed from a one-piece made up of a shirt or blouse sewn on to a skirt. This started to gain popularity during the Warring States period (others say these one-piece garments were already in evidence during the Zhou Kingdom) and remained in fashion up to the Han. The well-known long, unlined gowns for men, and the wrap-around dresses for women of later ages all developed down this line. Han Chinese clothing began with the shirt and skirt two-piece combination and was followed by many different kinds of one-pieces that appeared later. Every change in trend through the ages is actually attributable to the impact of external fashion on China. 不過畫像磚的西王母,衣飾、裝扮,是漢人隨時人的風尚而繪畫的,那是讓古代的人或神穿上漢人的衣服。中國古典服裝兩大傳統:一個是上衣下裳,始自商周;後來發展出襦裙等。另一個則是衣裳上下相連的深衣,戰國時開始流行(另一說則周代已有),至漢大盛,後世發展出長衫、旗袍等。漢族衣飾先有上衣下裳,然後出現各種深衣。每次產生變化,其實都由於外來的衝擊。

As for Yi the Archer and his wife Chang’e, their story is one we all know well. I tailored a piece of leather for Yi to wear as a skirt. The name of his skirt comes from the early period. The sides of the skirt were not supposed to be sewn up. Chang’e is wearing a knife-pleat ‘hundred-fold skirt’, with a delicate chiffon wrap around her shoulders allowing for extra movement. Skirts in the Han dynasty consisted of a single piece of material wrapped around the waist like a tube. 至於后羿和嫦娥的故事,我們都熟悉。我剪了皮革給后羿穿。早期的裙名叫「裳」,身側並不縫合。嫦娥穿百褶裙,加上飄帶,增加動感。「裙」是漢代的稱呼,由整幅布圍在腰間成筒形。

Yi is carrying a bow and arrows. The arrows were stored on his back in a quiver called a fu 菔, something usually made out of bamboo or cane. A quiver like this could hold up to ten arrows, with the arrows bundled tip down, the feathers and shafts poking out of the top. By the Tang dynasty, the fu became a hulu 胡祿: a pouch slung from a large belt around the waist. A hulu could hold thirty arrows. Hulu made from wild boar hide were used to sound out invading enemy troops. It was claimed that a scout could detect sounds of movement up to thirty li away by listening to the vibrations in the ground through a hulu placed on the ground as an amplifier. 后羿揹了弓和箭,箭放在衣背的袋囊中,箭袋名叫菔,一般用竹或籐製。一個箭菔可裝十支箭。箭簇向下,羽毛和箭杆露於袋外。到了唐代,箭箙的名字變成胡祿,垂掛在腰間鞶帶上,一個胡祿可裝三十支箭。用野豬皮做的胡祿,除了裝箭,把空胡祿放在地上,讓探子枕卧,據說可以聽到三十里外敵方人馬的動靜。

***

Mid-Autumn Festival

燕京歲時記 · 中秋

Pekinese call the festival of the eighth month the Zhongqiu 中秋, and every year at this time noble families make presents to one another of moon cakes 月餅. and various fruits. This, the fifteenth day, is the time when the moon is full, and so melons and fruits are laid out in the courtyards as offerings to her. Sacrifices are also made with yellow beans (intended for the rabbit in the moon), and cockscomb flowers (the flower of the month). At this time the white disk of the moon hangs in the void, and when the tinted clouds first begin to scatter, windups are arranged with bowls washed amidst the noisy hubbub of children. Verily it is what one may call a beautiful festival. However, at this time of making offerings to the moon, men usually do not make an obeisances, so that there is a Peking proverb which says: ‘Men do not bow to the moon. Women do not sacrifice to the God of the Kitchen’ 男不拜月,女不祭竈.

(Note: This is because the moon is supposed to belong to the yin or female principle, just as the sun is male or yang. Therefore it would be inappropriate for a man to worship the moon, whereas as the head of the household he would naturally sacrifice to the God of the Kitchen.

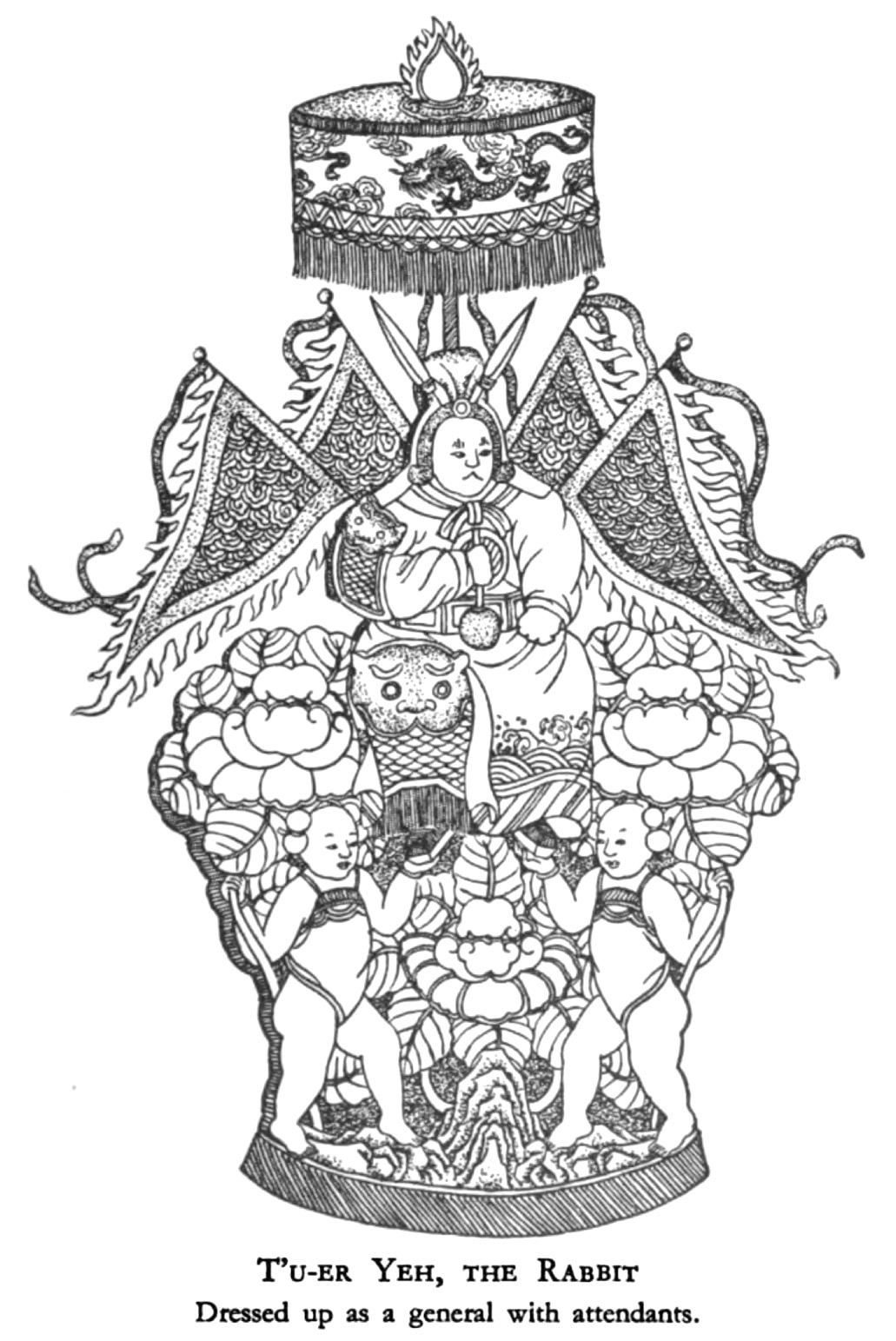

Moon Effigies 月光馬兒

Pekinese call the effigy of a deity, the deity’s ma’er 馬兒, not daring to speak directly of it itself as a deity. Moon effigies 月光馬兒 are made out of paper, on the upper part of which is painted the Goddess of the Moon 太陰星君, having the form of a Bodhisattva. Below is painted the ‘palace of the moon’ 月宮 (i.e., the moon’s disk), with the jade rabbit who pounds drugs like a man and holding a pestle. (The moon is inhabited, according to Taoist conception, by such a rabbit, who is forever busy pounding up the elixir of life.)

Many shops sell such objects, of which the tall ones may be seven or eight feet high, whereas the short ones are only two or three feet. On their tops are two pennants (one at each corner) which are made red, blue, or yellow. One places them facing the moon and offers them, at the same time burning incense and making obeisances. When the sacrifice is finished, they are all burned, other with such things as ‘thousand sheets’ 千張 and yuanbao 元寶 … …

(Note: These are both forms of ‘spirit money’, that is, imitation paper money to be burned for the dead. The first is cut int he form of a series of connected zigzag strips (the ‘thousand sheets’), while the second is circular like metal coins.) … …

Moon Cakes 月餅

For the Zhongqiu moon cakes, the Studio of Perfect Beauty 致美齋 at Qianmen, is the best place in the capital, whereas those of other places are not worth eating. But as for moon cakes to be used solely as moon offerings, every shop has them. The big ones are more than a foot in diameter, and have portrayed on their tops the images of the three-legged toad and the rabbit of the moon. (Note: This toad 蟾蜍 or 癞蛤蟆, like the jade rabbit 玉兔, is also an inhabitant of the moon, and some legends say that he is really the Goddess of the Moon, who was transformed into a toad.) Some people eat these cakes as soon as the sacrifices to the moon are completed, whereas other people keep them until New Year’s Even before eating them. They are called full moon cakes 團圓餅.

(Note: These cakes are of early origin, but the little paper squares stuck on them, according to a story, not found, however, in the orthodox histories, go back to the latter part of the Yuan dynasty. At this time the Chinese were very closely watched by their Mongol overlords. Mongol spies were stationed in private families; people were not permitted to gather into groups for conversation; and no weapons were permitted, even vegetable and meat choppers being restricted to one for every ten families. Finally, according to the story, someone conceived the idea of attaching papers to the moon cakes which are universally sent to one’s friends at this festival, and of writing thereon a message for uprising. The resulting midnight massacre of Mongols led to the ultimate overthrow of the dynasty.)

— from Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking,

as recorded in the Yanjing suishiji 燕京歲時記,

by Tun Li-Ch’en, translated and annotated by Derk Bodde,

Peip’ing: Henri Vetch, 1936, pp.64-67.

Romanised words have been converted to Hanyu pinyin.

***

A Mid Autumn Night at Tiger Hill

虎丘中秋夜

Zhang Dai (1597–1679)

張岱

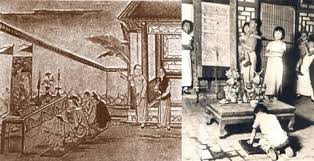

On the fifteenth of the eighth month people assemble on Tiger Hill: natives and visitors, scholar-gentry and their families, girl instrumentalists and singers, famous artistes of the ballad and dames of the stage, young wives and respectable daughters from among the common people, virile lads and pretty boys, and also drifters and profligates and young ne’er-do-wells, retainers and hangers on, serving-men and vagabonds, all cluster like scales on a fish. 虎丘八月半,土著流寓、士夫眷屬、女樂聲伎、曲中名妓戲婆、民間少婦好女、崽子孌童及游冶惡少、清客幫閒、傒僮走空之輩,無不鱗集。

The spread rugs and seat themselves wherever they can, from Shenggong’s Dais, the Thousand Men Rock, Crane Brook, the Sword-washing Pool, and the Petition Shrine, all the way down to the Sword-testing Stone and the first and second gates. Viewed from a vantage point, the scene resembles the flocking of wild geese to rest on the sand, or sunset clouds layering the river. 自生公台、千人石、鵝澗、劍池、申文定祠下,至試劍石、一二山門,皆鋪氈席地坐,登高望之,如雁落平沙,霞鋪江上。

When it grows dark and the moon appears, then sounds of pipe and drum arise from scores and hundreds of points, louder and louder, with clash of cymbal, boom of great Yuyang tympani, moving earth and reaching heaven, surging and boiling like thunder and lightning, so that one could shout at one’s neighbor and still not be heard. As the watches begin, the noise of drum and cymbal gradually subsides, to be replaced by a wealth of wind and string instruments, to which singing is joined, all major pieces for ensemble singing like ‘Brocade Sails Unfurl’ and ‘Across Lake’s Limpid Acres’.天暝月上,鼓吹百十處,大吹大擂,十番鐃鈸,漁陽摻撾,動地翻天,雷轟鼎沸,呼叫不聞。更定,鼓鐃漸歇,絲管繁興,雜以歌唱,皆錦帆開,澄湖萬頃同場大曲,蹲踏和鑼絲竹肉聲,不辨拍煞。

…更深,人漸散去,士夫眷屬皆下船水嬉,席席徵歌,人人獻技,南北雜之,管弦迭奏,聽者方辨句字,藻鑒隨之。二鼓人靜,悉屏管弦,洞蕭一縷,哀澀清綿,與肉相引,尚存三四,迭更為之。三鼓,月孤氣肅,人皆寂闃,不雜蚊虻。一夫登場,高坐石上,不簫不拍,聲出如絲,裂石穿雲,串度抑揚,一字一刻。聽者尋入針芥,心血為枯,不敢擊節,惟有點頭。然此時雁比而坐者,猶存百十人焉。使非蘇州,焉討識者。

— trans. Cyril Birch from, Scenes for Mandarins:

The Elite Theatre of the Ming.

***

As her bright wheel starts on its starry ways,

On earth ten thousand heads look up and gaze.

An Episode from The Story of the Stone

Zhen Shi-yin celebrates the full autumn moon with his friend Jia Yu-cun, a younger scholar in an episode from Chapter 1 of The Story of the Stone.

The Mid Autumn festival arrived and, after the family convivialities were over, Shi-yin had a little dinner for two laid out in his study and went in person to invite Yu-cun, walking to his temple lodgings in the moonlight. 一日,早又中秋佳節。士隱家宴已畢,乃又另具一席於書房,卻自己步月至廟中來邀雨村。

Ever since the day the Zhens’ maid had, by looking back twice over her shoulder, convinced him that she was a friend, Yu-cun had had the girl very much on his mind, and now that it was festival time, the full moon of Mid Autumn lent an inspiration to his romantic impulses which finally resulted in the following octet: 原來雨村自那日見了甄家之婢曾回顧他兩次,自謂是個知己,便時刻放在心上。今又正值中秋,不免對月有懷,因而口占五言一律云:

Ere on ambition’s path my feet are set,

Sorrow comes often this poor heart to fret.

Yet, as my brow contracted with new care,

Was there not one who, parting, turned to stare?

Dare I, that grasp at shadows in the wind,

Hope, underneath the moon, a friend to find?

Bright orb, if with my plight you sympathize,

Shine first upon the chamber where she lies.

未卜三生願,

頻添一段愁。

悶來時斂額,

行去幾回頭。

自顧風前影,

誰堪月下儔。

蟾光如有意,

先上玉人樓。

Having delivered himself of this masterpiece, Yu-cun’s thoughts began to run on his unrealized ambitions and, after much head-scratching and many heavenward glances accompanied by heavy sighs, he produced the following couplet, reciting it in a loud, ringing voice which caught the ear of Shi-yin, who chanced at that moment to be arriving: 雨村吟罷,因又思及平生抱負苦未逢時,乃又搔首對天長嘆,復高吟一聯云:

The jewel in the casket bides till one shall come to buy.

The jade pin in the drawer hides, waiting its time to fly.

玉在匱中求善價,

釵於奩內待時飛。

Shi-yin smiled. ‘You are a man of no mean ambition, Yu-cun.’ 恰值士隱走來聽見,笑道:雨村兄真抱負不淺也。

‘Oh no!’ Yu-cun smiled back deprecatingly. ‘You are too flattering. I was merely reciting at random from the lines of some old poet. But what brings you here, sir?’ 雨村忙笑道:豈敢!不過偶吟前人之句,何敢狂誕至此。因問:老先生何興至此。

‘Tonight is Mid Autumn night,’ said Shi-yin. ‘People call it the Festival of Reunion. It occurred to me that you might be feeling rather lonely here in your monastery, so I have arranged for the two of us to take a little wine together in my study. I hope you will not refuse to join me.’ 士隱笑道:今夜中秋,俗謂團圓之節,想尊兄旅寄僧房,不無寂寞之感,故特具小酌,邀兄到敝齋一飲,不知可納芹意否。

Yu-cun made no polite pretence of declining. ‘Your kindness is more than I deserve,’ he said. ‘I accept gratefully.’ And he accompanied Shi-yin back to the study next door. 雨村聽了,並不推辭,便笑道:既蒙厚愛,何敢拂此盛情。說著,便同士隱復過這邊書院中來。

Soon they had finished their tea. Wine and various choice dishes were brought in and placed on the table, already laid out with cups, plates, and so forth, and the two men took their places and began to drink. At first they were rather slow and ceremonious; but gradually, as the conversation grew more animated, their potations too became more reckless and uninhibited. The sounds of music and singing which could now be heard from every house in the neighbourhood and the full moon which shone with cold brilliance overhead seemed to increase their elation, so that the cups were emptied almost as soon as they touched their lips, and Yu-cun, who was already a sheet or so in the wind, was seized with an irrepressible excitement to which he presently gave expression in the form of a quatrain, ostensibly on the subject of the moon) but really about the ambition he had hitherto been at some pains to conceal: 須臾茶畢,早已設下杯盤,那美酒佳肴,自不必說。二人歸坐,先是款斟漫飲,次漸談至興濃,不覺飛觥限斝起來。當時街坊上家家簫管,戶戶弦歌。當頭一輪明月,飛彩凝輝,二人愈添豪興,酒到杯乾。雨村此時已有七八分酒意,狂興不禁,乃對月寓懷,口號一絕云:

In thrice five nights her perfect O is made,

Whose cold light bathes each marble balustrade.

As her bright wheel starts on its starry ways,

On earth ten thousand heads look up and gaze.

時逢三五便團圓,

滿把晴光護玉欄。

天上一輪才捧出,

人間萬姓仰頭看。

‘Bravo!’ said Shi-yin loudly. ‘I have always insisted that you were a young fellow who would go up in the world, and now, in these verses you have just recited, I see an augury of your ascent. In no time at all we shall see you up among the clouds! This calls for a drink!’ And, saying this, he poured Yu-cun a large cup of wine.士隱聽了,大叫:妙哉!吾每謂兄必非久居人下者,今所吟之句,飛騰之兆已見,不日可接履於雲霓之上矣。可賀!可賀!乃親斟一斗為賀。

Yu-cun drained the cup, then, surprisingly, sighed: 雨村因乾過,嘆道:

‘Don’t imagine the drink is making me boastful, but I really do believe that if it were just a question of having the sort of qualifications now in demand, I should stand as good a chance as any of getting myself on to the list of candidates. The trouble is that I simply have no means of laying my hands on the money that would be needed for lodgings and travel expenses. The journey to the capital is a long one, and the sort of money I can earn from my copying is not enough —’ 非晚生酒後狂言,若論時尚之學,晚生也或可去充數沽名,只是目今行囊、路費一概無措,神京路遠,非賴賣字撰文即能到者。

‘Why ever didn’t you say this before?’ said Shi-yin interrupting him. ‘I have long wanted to do something about this, but on all the occasions I have met you previously, the conversation has never got round to this subject, and I haven’t liked to broach it for fear of offending you. Well, now we know where we are. I am not a very clever man, but at least I know the right thing to do when I see it. Luckily, the next Triennial is only a few months ahead. You must go to the capital without delay. A spring examination triumph will make you feel that all your studying has been worth while. I shall take care of all your expenses. It is the least return I can make for your friendship.’ 士隱不待說完,便道:兄何不早言。愚久有此心意,但每遇兄時,兄並未談及,愚故未敢唐突。今既及此,愚雖不才,『義利』二字卻還識得。且喜明歲正當大比,兄宜作速入都,春闈一戰,方不負兄之所學也。其盤費餘事,弟自代為處置,亦不枉兄之謬識矣。

And there and then he instructed his boy to go with all speed and make up a parcel of fifty tales of the best refined silver and two suits of winter clothes. 當下即命小童進去,速封五十兩白銀,並兩套冬衣。

‘The almanac gives the nineteenth as a good day for travelling,’ he went on, addressing Yu-cun again. ‘You can set about hiring a boat for the journey straight away. How delightful it will be to meet again next winter when you have distinguished yourself by soaring to the top over all the other candidates!’ 又云:十九日乃黃道之期,兄可即買舟西上,待雄飛高舉,明冬再晤,豈非大快之事耶。

Yu-cun accepted the silver and the clothes with only the most perfunctory word of thanks and without, apparently, giving them a further moment’s thought, for he continued to drink and laugh and talk as if nothing had happened. It was well after midnight before they broke up. 雨村收了銀衣,不過略謝一語,並不介意,仍是吃酒談笑。那天已交三鼓,二人方散。

— Cao Xueqin, The Story of the Stone,

Volume 1: The Golden Days, Chapter 1,

translated by David Hawkes.

***

Mid Autumn at the Pavilion of Surging Waves

The following episode is from Shen Fu’s Six Records of the Fleeting World 浮生六記 said to have been completed in 1808.

夫天地者,萬物之逆旅也;

光陰者,百代之過客也。

而浮生若夢,為歡幾何。

— 李白《春夜宴从弟桃李园序》

On the fifteenth of the eighth moon, or the Mid-Autumn Festival, I had just recovered from my illness. Yun had now been a bride in my home for over half a year, but still had never been to the Canglang Pavilion itself next door. 中秋日,余病初愈。以芸半年新婦,未嘗一至間壁之滄浪亭。

So I first ordered an old servant to tell the watchman not to let any visitors enter the place. Toward eventing, I went with Yun and my younger sister, supported by an amah and a maid-servant and led by an old attendant. We passed a bridge, entered a gate, turned eastwards and followed a zigzag path into the place, where we saw huge grottoes and abundant green trees. The Pavilion stood on the top of a hill. 先令老僕約守者勿放閒人,於將晚時,偕芸及余幼妹,一嫗一婢扶焉,老僕前導,過石橋,進門折東,曲徑而入。疊石成山,林木蔥翠,亭在土山之巔。

Going up by the steps to the top, one could look around for miles, where in the distance chimney smoke arose from the cottages against the background of clouds of rainbow hues. Over the bank, there was a grove called the ‘Forest by the Hill’ where the high officials used to entertain their guests. Later on, the Zhengyi College was erected on this spot, but it wasn’t there yet. 循級至亭心,周望極目可數里,炊煙四起,晚霞燦然。隔岸名近山林;為大憲行台宴集之地,時正誼書院猶未啓也。

We brought a blanket which we spread on the Pavilion floor, and then sat round together, while the watchman served us tea. 攜一毯設亭中,席地環坐,守著烹茶以進。

After a while, the moon had already arisen from behind the forest, and the breeze was playing about our sleeves, while the moon’s image sparkled in the rippling water, and all worldly cares were banished from our breasts. 少焉,一輪明月已上林梢,漸覺風生袖底,月到波心,俗慮塵懷,爽然頓釋。

‘This is the end of a perfect day,’ said Yun. ‘Wouldn’t it be fine if we could get a boat and row around the Pavilion!’ At this time, the lights were already shining from people’s homes, and thinking of the incident on the fifteenth night of the seventh moon, we left the Pavilion and hurried home. 芸曰:今日之遊樂矣!若駕一葉扁舟,往來亭下,不更快哉。時已上燈,億及七月十五夜之驚,相扶下亭而歸。

According to the custom at Suzhou, the women of all families, rich and poor, came out in groups on the Mid-Autumn night, a custom which was called ‘pacing the moonlight’. Strange to say, no one came to such a beautiful neighbourhood as the Canglang Pavilion. 吳俗,婦女是晚不拘大家小戶皆出,結隊而游,名曰走月亮。滄浪亭幽雅清曠,反無一人至者。

— from the chapter ‘On Wedded Bliss’ 閨房記樂,

trans. Lin Yutang 林語堂, with minor stylistic modification.

***

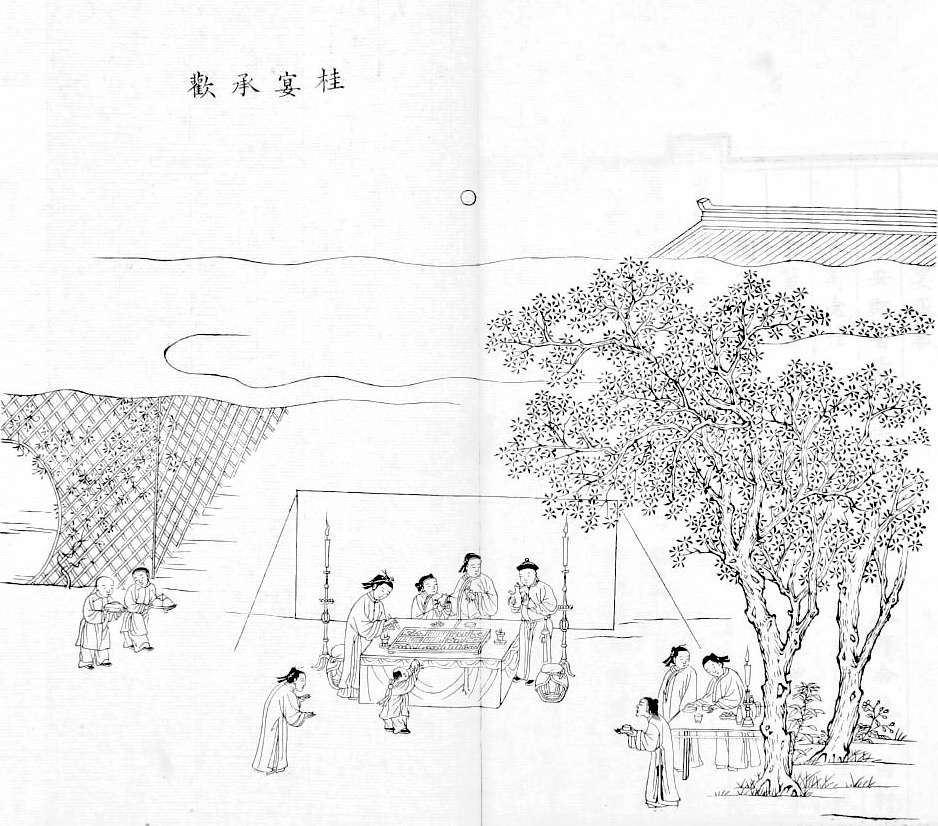

The Cassia Banquet 桂宴承歡

Wanggiyan Lincing 完顏麟慶

Translated by Yang Tsung-han 楊宗翰,

edited by Rachel May and Christina Sanderson

Titled ‘Cassia Banquet to Make Mother Happy’ 桂宴承歡 this episode is taken from the Manchu Bannerman Lincing’s (Linqing 麟慶, 1791-1846) Tracks in the Snow 鴻雪因緣圖記, the translation and annotation of which was initiated by John Minford. It is one of the Projects of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology.

The cassia tree, and a woodcutter, forever chopping down the tree, are legendary features of the moon. As soon as the tree is felled, it regrows as its essence is said to be life-giving.

— The Editor

In front of the Tower of Purple Verdure 紫翠樓 in the compound of the Xin’an 新安 Prefectural Office and Residence stood two cassia 桂 trees. The circumference of one of these trunks was so large it required both arms of a person to enclose it. There was also an ancient one from the days of the Six Dynasties, of which only half the trunk remained. The outer bark was cracked but the remaining trunk was substantial. In the autumn there were not many blossoms, yet their fragrance was exuberant and surpassed that of ordinary cassia flowers. In the eighth month of the year jiashen 甲申 [1824], I received a new appointment that transferred me to the Prefecture of Yingzhou 穎州. I handed over the seal of Huizhou Prefecture.

When the work of the Veritable Record of the Emperor Renzong 仁宗 Rui睿 was accomplished, all those still working in the Office were graciously rewarded whereas the officers who had left the Office already were just ‘honourably recorded’ in their Curriculum Vitae. The honorary rank of Circuit Intendant 道銜 was bestowed by edict to myself Lincing alone. Two lengths of silk were also bestowed, as well as five thin plates 鉼 of silver, which were sent down to Huizhou. On receiving these I kowtowed in the direction of the Imperial Palace and also petitioned the Governor of Anhui to beg him to present a memorial of thanksgiving and gratitude to the Sovereign on my behalf.

I presented the silk and the silver to my mother. She ordered that the silver be entrusted to the silver-smith to make spoons or other articles to be used at sacrificial rituals in our family Ancestral Temple to glorify and commemorate the Sovereign’s bestowals. She ordered that the two pieces of silk be made into a coverlet to be placed on the body of the deceased in the coffin — in substitution of a dhāraṇī quilt embroidered with lines from the Buddhist sutras — to express our gratitude to the Sovereign’s favour.

During the interval between my posts, I was unoccupied and enjoying my leisure. I therefore provided feasts and engaged players to give dramatic performances to thank my friends who had been coming to congratulate me. In the evening of the Mid-Autumn Festival — the fifteenth day of the eighth month — I provided a family feast under the two cassia trees. The moon was as radiant as water, and the flowers were more dazzling than gold. With red candles glowing, and splendid sumptuous dishes repeatedly served, I, Lincing, raised my goblet to pledge and wish my mother longevity. My wife offered chop-sticks and my daughter Miaolianbao 妙蓮保 broke open a pomegranate to offer to her grandmother while affectionately sitting at her grandmother’s knees. Presently, somebody delivered some Immortal Yellow Peaches from Huangshan 黃山仙桃, which my eldest son Chongshi 崇實 (who was then five years old, having been born in the seventh month of the year gengyin 庚寅 [1830]) took and offered to my mother, who looked upon him with delight. Mother was so glad and told us to enjoy ourselves and to drink to our hearts’ content.

Steeped in imperial favour 國恩 and family happiness 家慶, the felicity of the party guests and the brightness of the moon were both in perfect plenitude. Even the enviable felicities of the celestial immortals — I supposed — could be no greater than the blessings which we enjoyed that night.

***

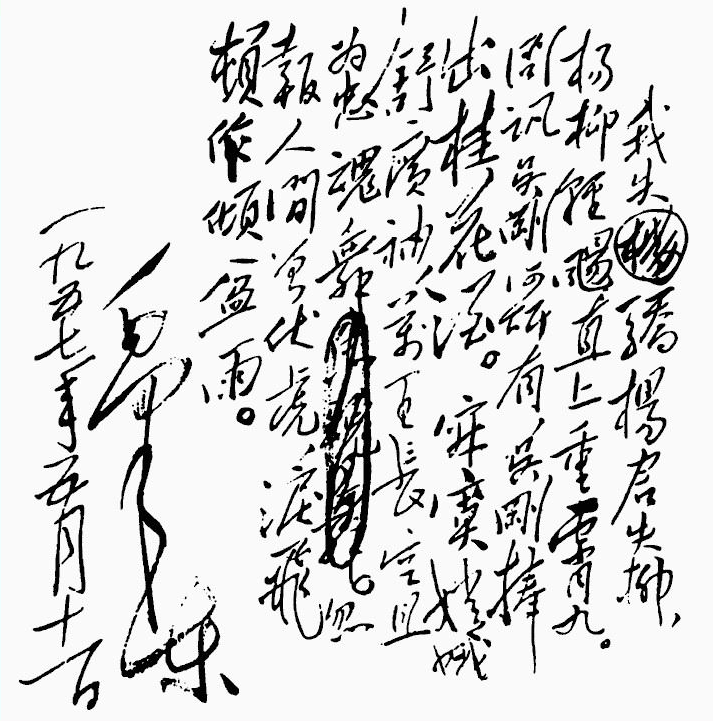

Mao Zedong’s Lonely Mood Goddess

Reply to Li Shuyi

— to the tune of Die lian hua

答李淑一

蝶戀花

Mao Zedong

毛澤東

11 May 1957

The following poem, made famous as a performance piece during the Cultural Revolution, and subsequently sung, filmed and dramatised ever since, is noteworthy as a rare expression of humanity and sentiment by the steely revolutionary. The Willow 楊 referred to is Mao’s second wife, Yang Kaihui 楊開慧, executed in 1929 after having refused to denounce her husband, and father of her three children. Mao Anying, one of the children, was said to have been forced to witness her death. Anying subsequently died during the Korean War.

— The Editor

I lost my proud Poplar and you your Willow,

Poplar and Willow soar to the Ninth Heaven.

Wu Gang, asked what he can give,

Serves them a laurel brew.

The lonely moon goddess spreads her ample sleeves

To dance for these loyal souls in infinite space.

Earth suddenly reports the tiger subdued,

Tears of joy pour forth falling as mighty rain.

我失驕楊君失柳,

楊柳輕颺直上重霄九。

問訊吳剛何所有,

吳剛捧出桂花酒。

寂寞嫦娥舒廣袖,

萬里長空且為忠魂舞。

忽報人間曾伏虎,

淚飛頓作傾盆雨。

Celebrating Victory, a poem in regulated verse

五律.喜聞捷報

This poem, also by Mao, was written during the Mid-Autumn Festival of 1947. Under pressure from the Nationalist Army following the outbreak of Civil War the previous year, Mao and his Communist forces abandoned the guerrilla base at Yan’an. Trekking through northwest China at the time of the Reunion Festival and cut off from family (Jiang Qing and their daughters, see below), Mao marks the festival by composing these lines in celebration of a military victory.

秋風度河上,大野入蒼穹。

佳令隨人至,明月傍雲生。

故里鴻音絕,妻兒信未通。

滿宇頻翹望,凱歌奏邊城。

***

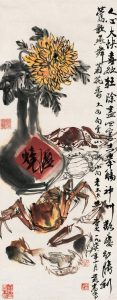

Celebrating with Crabs

Following years of warfare, from the time of the Northern Expedition of the late 1920s to the end of the Civil War on mainland China in 1949 (also known as ‘Liberation’ 解放), hard-won national unity and stable government promised a new era. Under Mao Zedong’s leadership, and with the support of his Communist Party colleagues, from the early 1950s what unfolded instead was three decades of domestic tragedy: families decimated, young pitted against old, broken friendships, lovers betrayed and country darkened by a pervasive atmosphere of suspicion and fear. Following Mao’s death in September 1976, people celebrated a ‘Second Liberation’ 第二次解放. With a ‘third age’ unfolding in China today some place their hopes in a fourth Liberation at some uncertain point in the future.

***

In the Lower Yangtze Valley, one of the gustatory delights of autumn is the eating of mitten crabs (also called ‘Shanghai hairy crabs’ 上海大閘蟹). Those from Yangcheng Lake 陽澄湖 near Suzhou are regarded as being a particular delicacy.

In October 1976, a mere month after Mao Zedong died in Beijing, a military coup led by Marshall Ye Jianying of the People’s Liberation Army and supported by Hua Guofeng, Mao’s final hand-picked successor, led to the arrest of key Cultural Revolution political figures known variously as the Gang of Four and the Shanghai Clique. These leaders — Wang Hongwen, Zhang Chunqiao, Jiang Qing (Mao’s widow) and Yao Wenyuan — were popularly despised by the party-state bureaucracy for their erratic and domineering behaviour, often described using the expression 横行霸道, to ‘run amok’ (literally, ‘walk sideways and be a hegemon controlling the roadway’). As crabs walk sideways, and the expression ‘run amok’ contains the term ‘walk sideways’ 横行, to celebrate their fall from power after ten years of chaotic misrule, people bought crabs in sets of four, three male and one female 三公一母, to eat while drinking sweet wine and cheering the end the Maoist era.

Soong Ching-ling 宋慶齡, widow of the founder of the 1912 Republic of China Sun Yat-sen, and the most famous fellow-traveller of the Communist Party (an organization she applied to join shortly before her death in 1981), is also said to have celebrated the ouster of the Gang of Four with a meal of four Shanghai hairy crabs.

***

Xi Dada’s Moons

‘Even the moon in foreign skies is rounder than that of China’ 外國的月亮比中國的圓 — this was a saying attributed to various disgruntled Republican-period (1912-1949) writers and thinkers. It reflected an ever-present sense of national inferiority, and the underlying humiliation, that had grown since the encounter of late-dynastic China with the mercantile Western Powers. Throughout much of the twentieth century, the roundest moon of all was thought to shine over the United States.

During the Maoist era (1949-1978), the saying ‘Even the moon in foreign skies is rounder than that of China’ was used to deride intellectuals and others deemed who were deemed to be ‘slaves of the West’. It was quoted with malicious intent by those party leaders, hacks and hitmen (and women) determined to stamp out support for foreign ideas and values.

As China’s People’s Republic strived to emulate all that was materially progressive about the West and Japan in the Reform era (1979-1992), the criticism of this expression, although ever-present, was more muted. In the post-1992 surge of neoliberal party-state economism, this saying has been employed more frequently; under Xi Jinping (2012-) it has taken on a menacing new tone.

In an internal speech on propaganda delivered on 19 August 2013, Xi directly addressed the issue of whether ‘the moon in foreign skies is rounder than that of China’. As Apple Daily in Hong Kong reported, when Xi discussed international news in the mass media (as opposed to China’s secretive party reporting and media system), he told his audience of official media leaders that, yes, it was important to report foreign news in an objective, thorough and realistic fashion, nonetheless, stronger leadership and Party guidance was essential. Certainly, both positive and negative stories should be reported, however, there must be strict oversight as it was crucially important that people did not get an impression that ‘even the moon in foreign skies was rounder than that of China.’

In the autumn of the first year of Xi Jinping’s ‘monarchy’, as an anti-corruption campaign was instituted throughout the party-state bureaucracy, the Chairman of Everything had mid-autumn moon cakes in his sights. At a ‘democratic lifestyle’ meeting convened by the provincial party committee of Hebei province between 23-25 September 2013, Xi Jinping declared that:

This Mid-Autumn Festival the Central Party Disciplinary Commission is focussing on moon cakes. They might appear to be a diminutive issue, but what they are after is the corruption that lurks behind moon cakes. [Cadres used gifts of moon cakes to give their superiors, clients and business people extravagant presents.] After getting our hands on Mid-Autumn, next is National Day, then New Year’s Day, then Chinese Lunar New Year, Qingming in April and on to the Double Fifth. By taking [these festivals] in hand, there will be positive results. It’ll become a habit, a fashion. 今年中秋节中央纪委抓月饼,看起来是小事,其实是抓这后面隐藏的腐败。抓了中秋节抓国庆节,抓了国庆节抓新年,抓了新年抓春节,抓了春节抓清明节、抓端午节,就这么抓下去,总会见效的,使之形成一种习惯、一种风气。

The official media went on to report that:

Following this speech by Xi Jinping, along with the ban on the giving of festive cards and well wishes, the ban on fireworks, etcetera, it became the regular practice of party committees at all levels in China to ‘issue bans on every festive occasion’. 在习近平此次讲话之后,包括贺卡禁令、爆竹禁令等等,“逢节必令”成为中国各级党政机关一种惯常举措。

Today, the moon over America, and other liberal democracies in the West, waxes and wanes erratically. Officially, China’s leaders express confidence that, even though pollution and smog-haze becloud the skies of the People’s Republic and frequently occlude Chang’e’s Lunar Palace, the moon over China will continue to wax.

***

Another, older, popular saying is: ‘The Toad Thinks it is Worthy of Eating the Flesh of a Swan’ 癩蝦蟆想吃天鵝肉. It means that unworthy people are self-deluded; the most ungainly think it their lot to enjoy rare delicacies. Since the Lunar Toad 蟾蜍, or 癞蛤蟆, is also believed to be none other than Chang’e, Goddess of the Moon, this would seem like a fitting conclusion to our Mid-Autumn New Sinology Jotting. On the eve of the Nineteenth Congress of the Chinese Communist Party scheduled to be held in Beijing from mid October 2017 perhaps this saying also addresses the overweening aspirations of China’s Chairman of Everything.