The Fifteenth Day of the First Month of the New Year 正月十五 marks the first full moon of the Lunar New Year. Generally called Yuanxiao 元宵, literally ‘First Evening’, it is also the height of the Lantern Festival 燈節 which was traditionally celebrated from the Hanging of Lanterns 上燈 on the Thirteenth Day to the Taking Down of Lanterns 落燈 on the Eighteenth Day of the First Month. The First Evening is also variously called: 上元節、小正月、元夕、小年 or 春燈節.

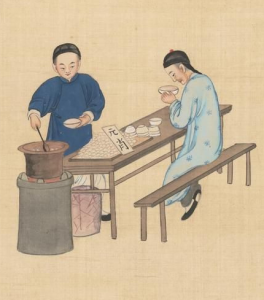

In 2017, the 11th of February marks the end of the Lunar New Year celebrations which began with the last day of the old year, New Year’s Eve 除夕, the 27th of January. The celebrations vary widely but they generally feature both domestic and public displays of lanterns 燈飾; these are supposed to mimic the full moon and symbolise the eating of Yuanxiao 元宵 (in the north) or Tangyuan 湯圓 (in the south): these are a kind of ball-shaped food made from glutinous rice flour. They are cooked and served in a soup made from the water they are boiled in. The balls can vary in colour and size depending on the region and may contain various sweet fillings such as sugary sesame or red bean paste, or indeed savoury flavours such as minced meat or vegetables. The shape and massing of Yuanxiao in a bowl is supposed to symbolise completion, togetherness and harmony.

One popular account holds that the general Yuan Shikai 袁世凱, who inveigled his way into becoming the president of the Republic of China (and would eventually, although unsuccessfully, attempt to restore dynastic rule by declaring himself emperor in 1916) favoured the term Soup Balls 湯圓, to Yuanxiao 元宵 which was a homophone for Yuan Xiao 袁消 ‘Yuan [Shikai] obliterated’.

These weeks since the Chinese New Year also mark an extraordinary period for the world since the inauguration of Donald Trump as the 45th President of the United States of America on the 20th of January. Turning modern tradition on its head, all that was new seems old again. Well indeed may one hope that the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice. What was a truism for China under the rule of the Chinese Communist Party and its Chairman of Everything Xi Jinping, now seems to hold equally for an America in the grip of Trump and the Republican Party. The ramifications of this temporal shift for The Year of the Rooster and far beyond are momentous.

For this reason, we have selected a number of episodes related to the Lantern Festival for our readers. The first features the art and life of Feng Zikai 豐子愷, a man whose creative career spanned the last years of dynastic China, the rise and fall of the Chinese Republic and the long years of High Maoism (1956-1976). He experienced, and created work, related to Lantern Festivals in all three eras.

We end with an intriguing chapter from China’s most famous novel, The Story of the Stone 石頭記 (also known as The Dream of the Red Chamber 紅樓夢). In Chapter 22, a Lantern Festival party ostensibly devoted to lighthearted games and riddles, reveals in coded form the tragic fate of key characters in the book. It also offers an insight into traditional Lantern Festival games while acting as a sombre reminder of how, all too often, dark auguries can be detected even at times of heedless celebration. Perhaps this is something that the politicians and their henchmen and women in this new Age of Authoritarians would do well to keep in mind.

This New Sinology Jotting on the Lantern Festival is the latest in a series of essays related to The Year of the Rooster previously published in China Heritage.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

The Fifteenth Day of the First Month of the

Dingyou Year of the Rooster 丁酉年正月十五

11 February 2017

Acknowledgements

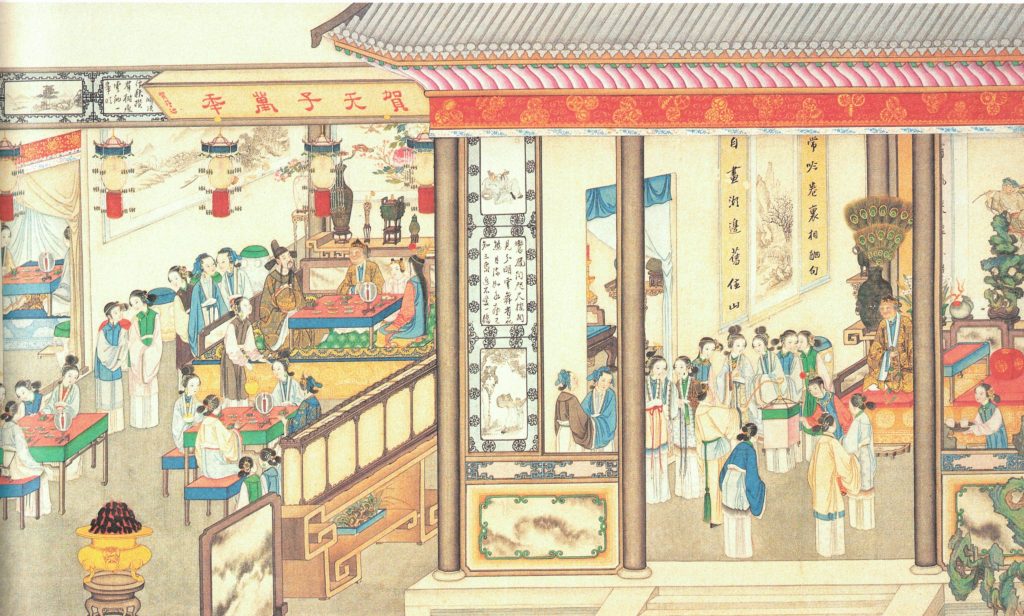

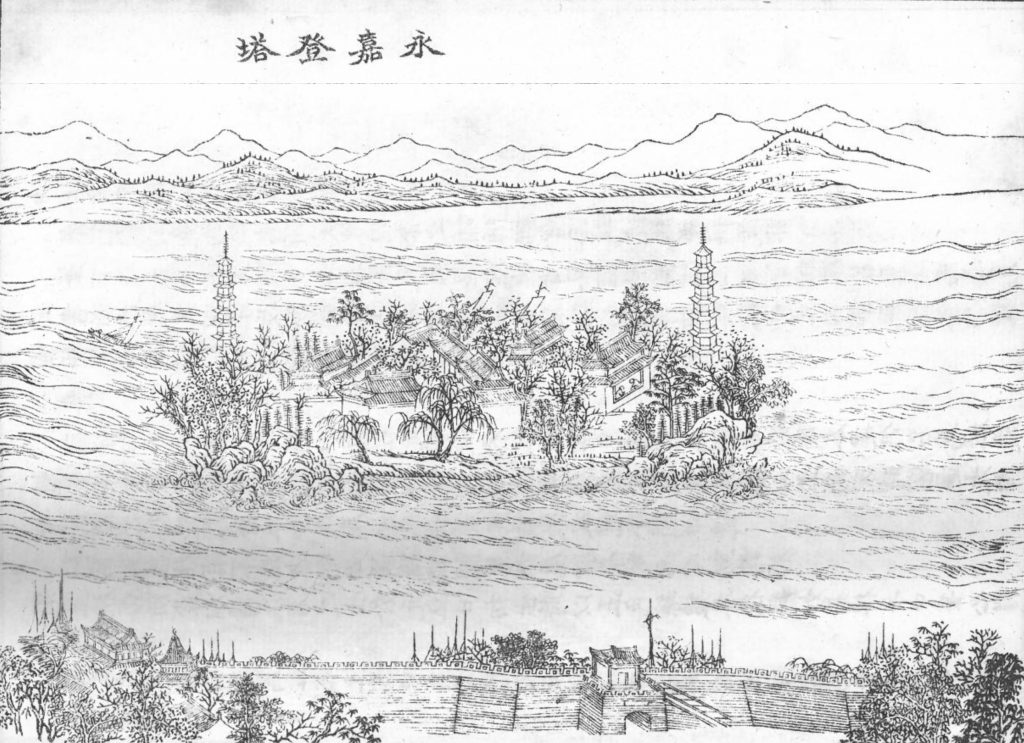

Annie Ren 任路漫, a PhD scholar working on The Story of the Stone 石頭記, checked the bilingual excerpt from Chapter 22 of the novel and added lines in Chinese from the Red Inkstone Commentaries 脂硯齋重評石頭記 found in the Gengchen version of the novel 庚辰本 (indicated by brackets, 【】). She also scanned the illustration by Sun Wen 孫溫 (1826-?) who painted scenes from The Story of the Stone over a thirty six-year period, from 1867 to 1903. Annie is working with John Minford on The Story of the Stone site that is part of China Heritage.

I am also grateful to Christina Sanderson for locating material in Linqing’s 麟慶 Tracks in the Snow 鴻雪因緣圖記 related to the Lantern Festival. Christina is finishing a translation of Linqing’s illustrated memoir with the support of an Australian Research Council grant awarded to John Minford and myself. Tracks in the Snow is one of the Projects of China Heritage.

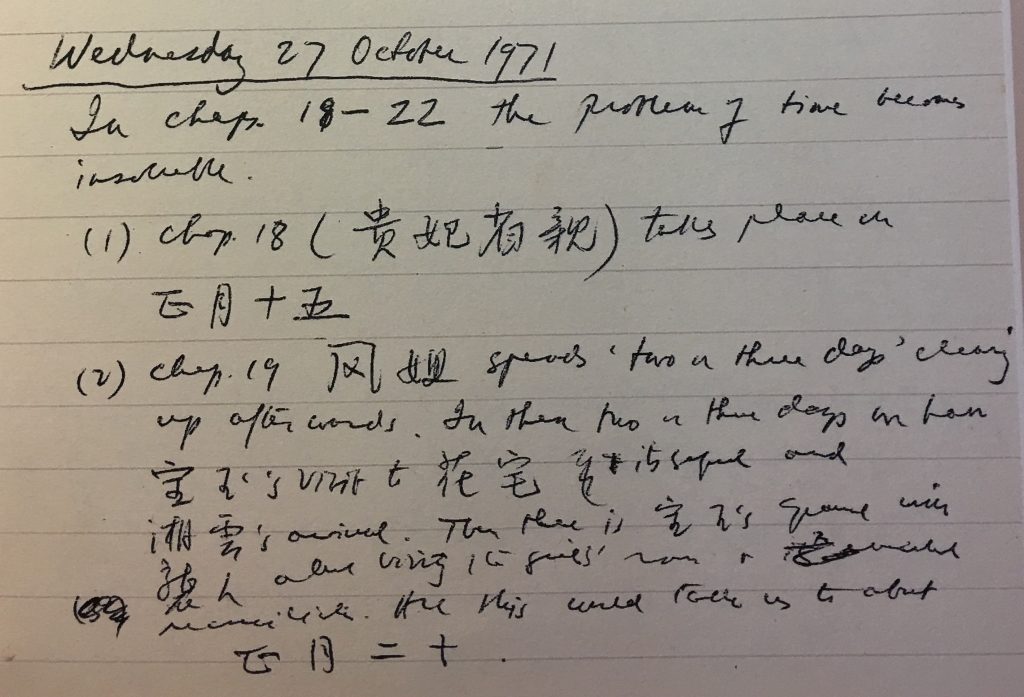

My thanks also to John Minford and the Estate of David Hawkes for permission to reproduce material from David’s translation of The Story of the Stone, Volume I, and his Translator’s Notebooks. &, as ever, I thank Lois Conner for allowing her work to grace these virtual pages.

— GRB

Palace Lanterns 宮燈 gained in popularity from the time of the Tang dynasty and were often presented to loyal ministers or those who were rewarded for valour or to favourites. The custom of making lanterns — also called 花燈、彩燈、燈籠 — gradually spread to the population at large and over time families, clans and villages made lanterns and created competitions for them, in particular around the time of Yuanxiao, or the Lantern Festival. The practice of putting riddles on lanterns outside one’s house as a test to passers-by also evolved (see more about Lantern Riddles below).

The most famous lantern/lamp is arguably the Chanxin Lamp 長信宮燈 dating from the Han dynasty, unearthed in 1968. However, since the Qing era, the city of Gaocheng 藁城 has been particularly celebrated for the manufacture of lanterns. These lanterns come in many shapes and sizes. Among the most popular are Square Official Cap Lantern 白帽方燈, Round Silk Lanterns 紗圓燈, Arhant Lanterns 羅漢燈, Galloping Horse Lanterns 走馬燈, and lanterns in the shape of butterflies 蝴蝶燈, or Two Dragons Chasing a Pearl 二龍戲珠燈. Particularly popular were images taken from ancient tales, famous novels and ghost stories, as were intricate paper cuts 剪紙 that were pasted on lanterns. Apart from Lantern Gazing 觀燈 on the streets, the week-long festivities included the exchange of gifts, Dragon Dances 舞龍, Lion Dances 舞獅, Stilt Walkers 踩高蹺, Dry-land Boat Floats 跑旱船, fireworks 放煙火, Welcoming the Purple Maiden 迎紫姑, Lantern Riddles 燈謎 (see below) and, inevitably, the eating of Yuanxiao 元宵.

Under the People’s Republic, the annual Lantern Festival was transformed as the Communist Party abrogated all forms of former public (and private) celebration in favour of its tireless self-congratulation (see, for example, Thirteen National Days, a retrospective). Huge Palace Lanterns were hung on Tiananmen Gate in the heart of the socialist capital, with smaller imitations bracketing the entrances to official yamen and work units, including factories of every description throughout the country (in reality, this also continued a dynastic tradition: in imperial Peking the Ministry of Works 工部, with its easy access to funds, was famous for its extravagant gate lanterns).

As life was increasingly drained from the private and individual, the bloated party-state lauded itself with every greater extravagance, as it does to this day. Red lanterns were first reclaimed by the filmmaker Zhang Yimou 張藝謀 in his 1991 film Raise the Red Lantern 大紅燈籠高高掛, and its title was soon being used, not to indicate patriarchal favouritism, as it does in the film, but to celebrate the festivities surrounding the Fifteenth Day of the First Month. Since then, local Lantern Festivals, which combine reinvented tradition, Party propaganda and commercial avarice have once more flourished, the most famous being the Qinhuai Lantern Festival 秦淮燈會 in Nanjing, which dates from 2006.

Lanterns in Three Eras

At Dynasty’s End

The local New Year’s Lantern Festival, celebrated on the full moon of the first lunar month of the traditional calendar, was of such moment the lantern would deck the town [of Shimenwan, Zhejiang province where Feng Zikai grew up] only once every few years or even few decades, unlike most other towns and districts. Writing at the age of thirty-seven (in 1935), Feng said he could only remember three occasions on which the festival had been held. One of these was in his early childhood. The family brought out a large traditional lantern from storage ready for the rare festival display. It was an old ‘coloured umbrella’ 彩傘, as the lanterns were called locally, that had been made by his father and his aunt Feng Zaohong when they were children. Adorned with felicitous images and calligraphic inscriptions on large paper strips stuck to its sides, the large hexagonal lantern was widely regarded as the finest in the town.

making my own lantern was the first time I derived a real sense of satisfaction form doing something ‘artistic’. Hanging it up inside our house after the festival, we took great pleasure in looking over it carefully and comparing it gleefully [with all the others we had seen]. Of course, it could hardly match the brilliance of the older lanterns, but by working on our own we had shared a sense of creativity, and it fired in me a desire to learn calligraphy and painting.

A Bankrupt Republic

Feng left his hometown in the 1910s to go to school in Hangzhou and Tokyo. Thereafter, he lived and worked in Shanghai as a teacher, artist and translator. For years he saved up so he and his large family could return to the countryside where he eventually designed and built a house, Yuanyuan Hall 緣緣堂, for the family, his library and his study. When he returned to Shimenwan in the 1930s, he found a town transformed:

With the passage of time and the devastation wrought on the economy by the depression, disastrous weather conditions, continued local strife, and political uncertainty, the artist stood by, a helpless witnesses the world of his youth vanished forever, the rituals and rhythms of agricultural life disrupted at every turn. After twenty years away from Shimenwan, even while delighting in his homecoming, he was sobered by the realisation that the place was much changed. Even the New Year’s celebrations were completely different from the way he remembered them. While the introduction of the Western calendar had undermined the significance of the Spring Festival for local families, bankruptcy had struck down so many once-viable commercial ventures in the town that it was impossible to hold the Lantern Festival in its traditional lavish style anymore. By now so many ‘people were living on the borderline of poverty, Zikai noted, that few even had the heart to celebrate the advent of yet another year.

Chiang Kai-shek’s New Life Movement

A few weeks earlier Feng Zikai had going the boatman onshore when they came upon a special village lantern festival, which had been organised as part of the New Life Movement. This was a military-style ethics-cum-etiquette campaign aimed at transforming the national character and improving public behaviour that had only recently been launched at the instigation of Chiang Kai-shek, the Nationalist Party leader. Mindless of the campaign’s ideological aims, the boatman was enthusiastic about the possibility of this unseasonal spectacle, a clamorous nighttime parade. Zikai was less impressed. In a guarded criticism of the propaganda crusade, Feng comments that he notice a boy with a drum on his back. A man was following behind, beating the instrument vigorously as part of the procession organised to stir up interest in the movement. Zikai thought the the boy was too young and frail to endure such an athletic evening. ‘All that beating would probably put his joints out of kilter, and his mother would have to put them back in place when he got home.’ After sketching the boy, he turns his attention to the music: ‘The beat was not as powerful or as inspiring as before, it now seemed to convey a desolate air.’

In the end, exhausted and bored, Feng remarks: ‘All I could make out was an endless array of lights the size of pingpong balls bobbing in front of my eyes …’

Mao Zedong’s People’s Republic

Feng Zikai, like so many other cultural figures and intellectuals educated before 1949, adjusted himself to the Communist regime hoping for the best but mindless of what would be the worst. Those with a more international, or US-oriented worldview were even decried for thinking that ‘The foreign moon is more round than China’s’ 美國的月亮比中國的圓.

Feng, along with a legion of others, first had to ‘wash in public’ 洗澡 by renouncing his past, and then he attempted to contribute to what all hoped would be a more peaceful and prosperous society. He was rewarded by the state for his compliance, although generally he avoided greater largesse and official blandishments, and therefore resiled from excessive sycophancy. Sometimes, however, it was impossible to avoid demands to extol the Party’s victories. One example from 1960 is particularly chilling. The country was being ravaged by the famine unleashed by Mao’s Great Leap Forward while artists and writers were called on to celebrate the new year and Lantern Festival.

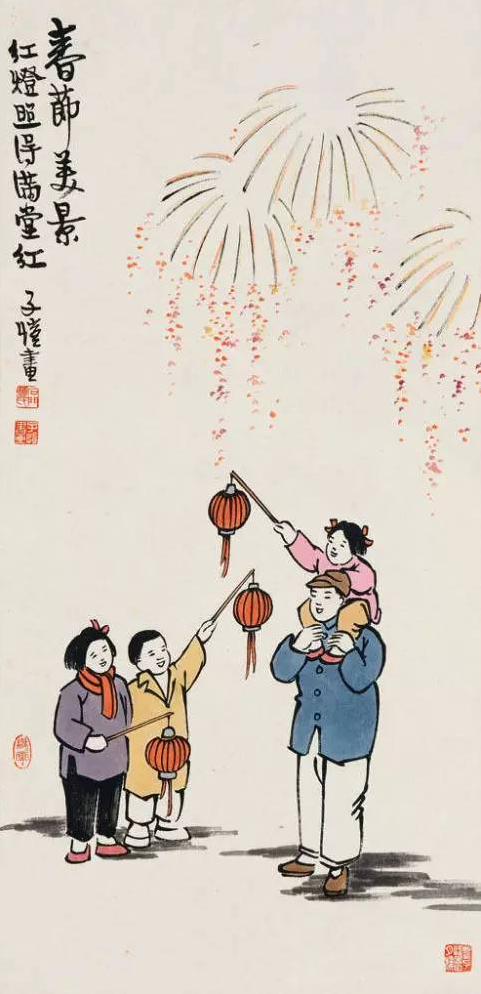

This work to the right is made the familiar style of Feng Zikai’s later paintings, even if it is a bit more stilted (the frozen faces of father and children give it away). It displays the de rigeuer bonhomie of cultural work in the first decades of the People’s Republic. Here Spring Festival and the Lantern Festival are celebrated by old and young alike, the manqué masses. In reality, at the time strict rationing meant that any celebrations were limited to a low calorie diet and muted celebrations. Regardless, ‘cultural workers’ were required to churn out hosannahs that shouted support in loud tones and bright colours. This sad picture brings to mind a famous 1935 French depiction of the depredations of the Soviet famine titled Nous sommes bien heureux, ‘We are Very Happy’.[3]

Guessing Riddles in The Story of the Stone

In a traditional China that was obsessed with written word and verbal dexterity, the ability to Guess Lantern Riddles 猜燈謎 was regarded as a talent no less impressive than a prowess to hunt tigers. Riddles inscribed on lanterns during the Yuanxiao Festival were referred to as ‘Lantern Tigers’ 燈虎 or ‘Literary Tigers’ 文虎 and guessing or solving riddles was known as ‘Shooting Tigers’ 射虎. To this day, people who are good at solving even the most obscure riddles are hailed as ‘Tiger-killing Generals’ 打虎將.

The style of a Riddle is as follows: Riddle 謎語 plus a Hint (often prefaced with the word 打), and the Solution 謎底. For example, from the text below:

The monkey’s tail reaches from tree-top to ground.

It’s the name of a fruit.

猴子身輕站樹梢。

—— 打一果名。

The answer being a longan berry or long’un (a long one)

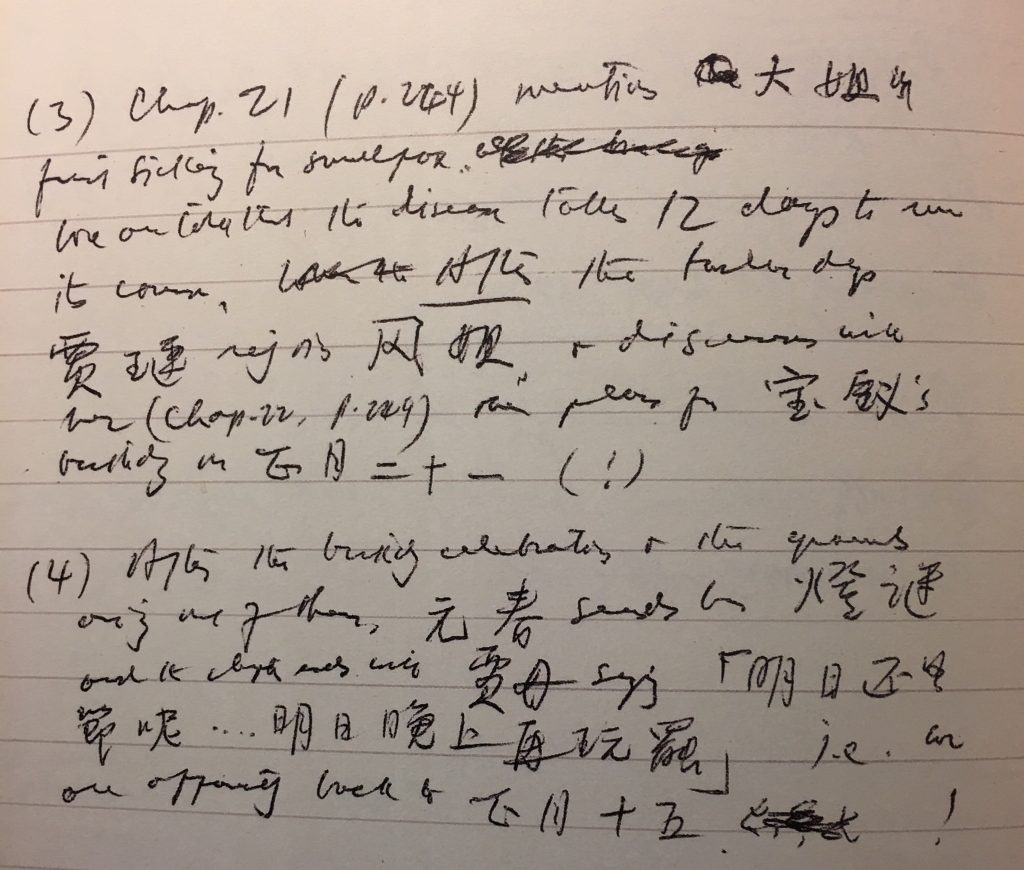

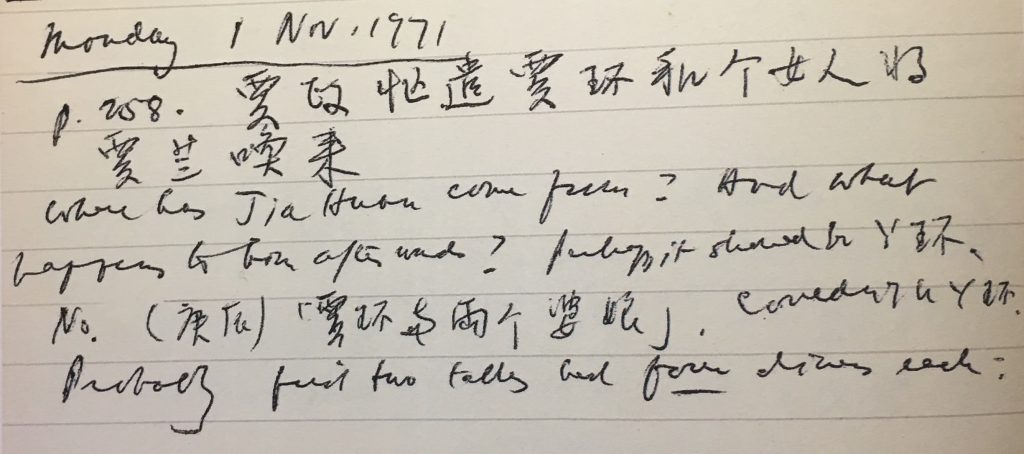

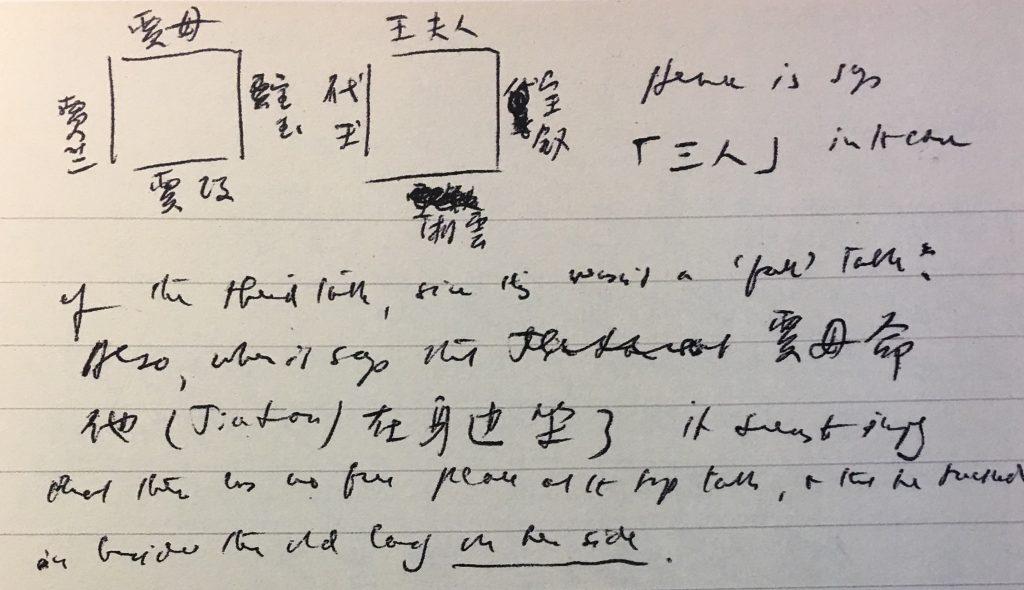

The following excerpt is from Chapter 22 of The Story of the Stone, translated by David Hawkes with illustrations from his Notebooks that touch on a few of the numerous conundrums created for the translator by different manuscript versions of the book:

Jia Zheng Sees Portents of Doom in Lantern Riddles

制燈謎賈政悲讖語

Just then it was announced that the Imperial Concubine had sent someone round from the Palace with a lantern-riddle which they were to try and guess. After they had guessed the answer, they were each to make up a riddle of their own and send it back to her. 忽然人報,娘娘差人送出一個燈謎兒,命你們大家去猜,猜著了每人也作一個進去。

As soon as they heard this, the four of them hurried to the reception room in Grandmother Jia’s apartment, where they found a young eunuch with a square, flat-topped lantern of white gauze specially made for hanging riddles on. There was one hanging on it already which they crowded round to read while the eunuch gave them their instructions: 四人聽說忙出去,至賈母上房。只見一個小太監,拿了一盞四角平頭白紗燈,專為燈謎而製,上面已有一個,眾人都爭看亂猜。小太監又下諭道:

‘When the young ladies have guessed, will they please not tell anyone the answer, but write it down secretly. The answers will be collected and taken back to the Palace in a sealed envelope so that Her Grace can see for herself who has guessed correctly.’ 眾小姐猜著了,不要說出來,每人只暗暗的寫在紙上,一齊封進宮去,娘娘自驗是否。

Bao-chai went up to the lantern and looked at the riddle, which was in the form of a quatrain. It was not a particularly ingenious one, but she felt obliged to praise it, and therefore remarked that it was hard to guess’ and pretended to have to think about the answer, though in truth it had been obvious to her at a glance. Bao-yu, Dai-yu, Xiang-yun and Tan-chun had also guessed the answer and were busy writing it down. Presently Jia Huan and Jia Lan were summoned, and they too wrote something down after a good deal of puzzling. After that everyone made up a riddle about some object of their choice, wrote it out in the best kai-shu on a slip of paper, and hung it on the lantern, which was then taken away by the eunuch. 寶釵聽了,近前一看,是一首七言絕句,并無甚新奇,口中少不得稱讚,只說難猜,故意尋思,其實一見就猜著了。寶玉、黛玉、湘雲、探春四個人也都解了,各自暗暗的寫了半日。一併將賈環、賈蘭等傳來,一齊各揣機心都猜了,【庚辰雙行夾批:寫出猜謎人形景,看他偏於兩次戒機後,寫此機心機事,足見作意至深至遠。】寫在紙上。然後各人拈一物作成一謎,恭楷寫了,掛在燈上。

Towards evening the eunuch returned and reported what the Imperial Concubine had had to say about the results: 太監去了,至晚出來傳諭:

‘Her Grace’s own riddle was correctly guessed by everyone except Miss Ying and Master Huan. Her Grace has thought of answers to all the riddles sent her by the young ladies and gentlemen, but she does not know whether or not they are correct.’ 前娘娘所製,俱已猜著,惟二小姐與三爺猜的不是。小姐們作的也都猜着了,不知是否。

He showed them the answers written down. Some were right and some were wrong, but even those whose riddles had been incorrectly answered deemed it prudent to pretend that the answers they had received were the right ones. 說著,也將寫的拿出來。也有猜著的,也有猜不著的,都胡亂說猜著了。

The eunuch proceeded to distribute prizes for answering the Imperial Concubine’s riddle. Everyone who had guessed correctly received an ivory note-case made by Palace craftsmen and a bamboo tea-whisk. Ying-chun and Jia Huan were the only ones who did not receive anything. Ying-chun treated the matter as a joke and rapidly dismissed it from her mind, but Jia Huan was very much put out. To make matters worse, the eunuch went on to query Jia Huan’s own riddle: 太監又將頒賜之物送與猜著之人,每人一個宮製詩筒,一柄茶筅,獨迎春、賈環二人未得。迎春自為頑笑小事,並不介意,賈環便覺得沒趣。且又聽太監說:

‘Her Grace says that she has not answered Master Huan’s riddle because she could not make any sense of it. She told me to bring it back and ask him what it means.’ 三爺說的這個不通,娘娘也沒猜,叫我帶回問三爺是個什麼。

Intrigued, the others crowded round to look. This is what Jia Huan had written: 眾人聽了,都來看他作的什麼,寫道是:

Big brother with eight sits all day on the bed;

Little brother with two sits on the roof’s head.

大哥有角只八個,二哥有角只兩根。

大哥只在床上坐,二哥愛在房上蹲。

【庚辰雙行夾批:可發一笑,真環哥之謎。諸卿勿笑,難為了作者摹擬。】

There was a loud laugh when they had finished reading it. Jia Huan told the eunuch the answer: a head-rest and a ridge-end. The eunuch made a note of it and, after taking tea, departed once more. 眾人看了,大發一笑。賈環只得告訴太監說:一個枕頭,一個獸頭。太監記了,領茶而去。

Fired with enthusiasm by Yuan-chun’s example, old Lady Jia decided to hold a riddle party. A very elegant lantern in the form of a three-leaved screen was hurriedly constructed on her orders and set up in the hall. When that had been done, she told all the boys and girls to make up a riddle – being careful to keep the answers to themselves – write it on a slip of paper, and stick it on her lantern-screen. Then, having prepared the best fragrant tea to drink, a variety of good things to eat, and lots of little gifts to serve as prizes, she was ready to begin. Jia Zheng observed the old lady’s excitement when he got back from Court and came along himself in the evening to join in the fun. 賈母見元春這般有興,自己越發喜樂,便命速作一架小巧精緻圍屏燈來,設於當屋,命他姊妹各自暗暗的作了,寫出來粘於屏上,然後預備下香茶細果以及各色玩物,為猜著之賀。賈政朝罷,見賈母高興,況在節間,晚上也來承歡取樂。

There were three tables. Grandmother Jia, Jia Zheng, Bao-yu and Jia Huan sat at the table on the kang, while below, Lady Wang, Bao-chai, Dai-yu and Xiang-yun sat at one table and Ying-chun, Tan-chun and Xi-chun at another. The floor below the kang was thronged with old women and maids in attendance. Li Wan and Xi-feng had a table to themselves in an inner room. 上面賈母、賈政、寶玉一席,下面王夫人、寶釵、黛玉、湘雲又一席,迎、探、惜三個又一席。地下婆娘丫鬟站滿。李宮裁、王熙鳳二人在裏間又一席。

‘Where’s my little Lan?’ said Jia Zheng, not seeing Jia Lan at any of the tables. 賈政因不見賈蘭,便問:怎麼不見蘭哥﹖

One of the serving-women went into the inner room to ask Li Wan. She rose to reply out of respect for her father-in-law: 地下婆娘忙進裏間問李氏,李氏起身笑著回道:

‘He refuses to come because he says his Grandpa Zheng hasn’t invited him.’ 他說方才老爺並沒去叫他,他不肯來。

The others were much amused when the woman relayed this answer back to Jia Zheng. 婆娘回覆了賈政。

‘He’s a stubborn little chap when he’s made his mind up!’ they said. But they thought none the worse of him for that. 天生的牛心古怪。

Jia Zheng quickly sent Jia Huan with two of the old women to fetch him. When he arrived, Grandmother Jia made him squeeze up beside her on her side of the table and gave him a handful of nuts and dried fruits to eat. The little boy’s presence provided the company with something to laugh and talk about. But not for long. Bao-yu, who normally did most of the talking on occasions like this, was today reduced by his father’s presence to saying no more than ‘yes’ and ‘no’ to remarks made by other people. As for the rest: Xiang-yun, in spite of her sheltered upbringing, was normally an animated, not to say indefatigable talker, but this evening she too seemed to have been afflicted with dumbness by Jia Zheng’s presence; Dai-yu was at the best of times unwilling to say very much in company from a sort of aristocratic lethargy which was a part of her nature; and Bao-chai, whose punctilious correctness made her always sparing in the use of words, even though on this occasion she was probably the least uncomfortable of those present, said little to advance the conversation. As a consequence, what should have been a jolly, intimate family party was painfully unnatural and restrained. 賈政忙遣賈環與兩個婆娘將賈蘭喚來。賈母命他在身旁坐了,抓果品與他吃。大家說笑取樂。往常間只有寶玉長談闊論,今日賈政在這裏,便惟有唯唯而已。【庚辰雙行夾批:寫寶玉如此。非世家曾經嚴父之訓者,斷寫不出此一句。】餘者湘雲雖係閨閣弱女,卻素喜談論,今日賈政在席,也自緘口禁言語。黛玉本性懶與人共,原不肯多語。寶釵原不妄言輕動,便此時亦是坦然自若。故此一席雖是家常取樂,反見拘束不樂。

Grandmother Jia knew as well as everyone else that this state of affairs was entirely owing to Jia Zheng’s presence, and after the wine had gone round for the third time, she attempted to drive him off to bed. Jia Zheng, for his part, was perfectly well aware that he was being driven away so that the younger people could feel freer to enjoy themselves and, smiling forcedly, appealed against his banishment: 賈母亦知因賈政一人在此所致之故,酒過三巡,便攆賈政去歇息。賈政亦知賈母之意,攆了自己去後,好讓他們姊妹兄弟取樂的。賈政忙陪笑道:

‘When they told me earlier today that you were planning to give a riddle party, I specially prepared a contribution to the feast so that I might come and join you. You have so much affection for your grandchildren, Mama. Can you not spare just a tiny bit for your son?’ 今日原聽見老太太這裏大設春燈雅謎,故也備了彩禮酒席,特來入會。何疼孫子孫女之心,便不略賜以兒子半點﹖

Grandmother Jia laughed: 賈母笑道:

‘They can’t talk naturally while you are here. All you are doing is making it gloomy for me. I can’t abide it. Well, if you’ve come to answer riddles, I’ll give you a riddle. But if you can’t guess the answer, you will have to pay me a forfeit.’ 你在這裏,他們都不敢說笑,沒的倒叫我悶。你要猜謎時,我便說一個你猜,猜不著是要罰的。

‘Yes, of course,’ said Jia Zheng eagerly. ‘And if I guess right, I shall expect to be given a prize.’ 賈政忙笑道:自然要罰。若猜著了,也是要領賞的。

‘Of course,’ said Grandmother Jia. 賈母道:這個自然。說著便念道:

The monkey’s tail reaches from tree-top to ground.

It’s the name of a fruit.

猴子身輕站樹梢。

—— 打一果名。

【庚辰雙行夾批:所謂「樹倒猢猻散」是也。】

Jia Zheng knew that the answer to this hoary old chestnut was ‘a longan’ (long ’un), but pretended not to, and made all kinds of absurd guesses, each time incurring the obligation to pay his mother a forfeit, before finally giving the right answer and receiving the old lady’s prize. Then he propounded a riddle of his own for her: 賈政已知是荔枝,便故意亂猜別的,罰了許多東西;然後方猜著,也得了賈母的東西。然後也念一個與賈母猜,念道:

My body’s square,

Iron-hard am I.

I speak no word,

But words supply.

It’s a useful object.

身自端方,

體自堅硬。

雖不能言,

有言必應。

—— 一用物。

He whispered the answer to Bao-yu, who, readily understanding what was expected of him, surreptitiously passed it on to Grandmother Jia. The old lady, having thought for a bit and decided that it sounded all right, said: 說畢,便悄悄的說與寶玉。寶玉意會,又悄悄的告訴了賈母。賈母想了想,果然不差,便說:

‘An inkstone.’ 是硯臺。

‘Bravo, Mamma! Right first time!’ said Jia Zheng, and turning round to address the servants, he asked them to bring in the presents for Lady Jia. There was an answering call from the women below, and presently a number of them came forward bearing trays and boxes of various shapes and sizes which they handed up onto the kang. Grandmother Jia examined them one by one. They all contained traditional Lantern Festival presents, but in new and exquisite designs and of the very highest quality. The old lady was obviously pleased. 賈政笑道:到底是老太太,一猜就是。回頭說:快把賀彩送上來。地下婦女答應一聲,大盤小盤一齊捧上。賈母逐件看去,都是燈節下所用所頑新巧之物,甚喜,

‘Come, children!’ she commanded jovially. ‘Give the Master a drink!’ 遂命:給你老爺斟酒。

Bao-yu stood up and poured wine from the wine-kettle into a little cup and Ying-chun handed it ceremoniously to her uncle. 寶玉執壺,迎春送酒。

‘Have a look at the riddles on the screen,’ said Grandmother Jia when Jia Zheng, with equal ceremony, had drained the cup. ‘They were all made up by the children. See if you can tell me the answers.’ 賈母因說:你瞧瞧那屏上,都是他姊妹們做的,再猜一猜我聽。

Jia Zheng rose from his seat and went up to the lantern-screen. The first riddle he saw was Yuan-chun’s: 賈政答應,起身走至屏前,只見頭一個寫道是:

At my coming the devils turn pallid with wonder.

My body’s all folds and my voice is like thunder.

When, alarmed by the sound of my thunderous crash,

You look round, I have already turned into ash.

An object of amusement.

能使妖魔膽盡摧,

身如束帛氣如雷。

一聲震得人方恐,

回首相看已化灰。

——打一玩物

【庚辰雙行夾批:此元春之謎。才得僥幸,奈壽不長,可悲哉!】

‘Would that be a firework?’ said Jia Zheng. 賈政道:這是炮竹嗎。

‘Yes,’ said Bao-yu. 寶玉答道:是。

Jia Zheng looked again, this time at Ying-chun’s: 賈政又看迎春的,道:

Man’s works and heaven’s laws I execute.

Without heaven’s laws, my workings bear no fruit.

Why am I agitated all day long?

For fear my calculations may be wrong.

A useful object.

天運人功理不窮,

有功無運也難逢。

因何鎮日紛紛亂,

只為陰陽數不同。

——打一用物

【庚辰雙行夾批:此迎春一生遭際,惜不得其夫何!】

‘An abacus?’ 賈政道:是算盤。

There was a laugh from Ying-chun: 迎春笑道:

‘Yes.’ 是。

The next riddle was Tan-chun’s: 又往下看,是探春的:

In spring the little boys look up and stare

To see me ride so proudly in the air.

My strength all goes when once the bond is parted,

And on the wind I drift off broken-hearted.

An object of amusement.

階下兒童仰面時,

清明妝點最堪宜。

游絲一斷渾無力,

莫向東風怨別離。

——打一玩物

【庚辰雙行夾批:此探春遠適之讖也。使此人不遠去,將來事敗,諸子孫不致流散也,悲哉傷哉!】

‘It looks as if that ought to be a kite’, said Jia Zheng. 賈政道:好像風箏。

‘Yes,’ said Tan-chun 探春笑道:是。

The next riddle he looked at was Dai-yu’s: 贾政再往下看,是黛玉的,道:

At court levée my smoke is in your sleeve:

Music and beds to other sorts I leave.

With me, at dawn you need no watchman’s cry,

At night no maid to bring a fresh supply.

My head burns through the night and through the day,

And year by year my heart consumes away.

The precious moments I would have you spare:

But come fair, foul, or fine, I do not care.

A useful object.

朝罷誰攜兩袖煙,

琴邊衾裏總無緣。

曉籌不用雞人報,

五夜無煩侍女添。

焦首朝朝還暮暮,

煎心日日復年年。

光陰荏苒須當惜,

風雨陰晴任變遷。

——打一用物

‘That must be an incense-clock.’ 賈政道:這個莫非是更香?

Bao-yu answered for her: 寶玉代言道:‘Yes.’ 是。

Jia Zheng looked at the next riddle:

Southward you stare,

He’ll northward glare.

Grieve, and he’s sad.

Laugh, and he’s glad.

A useful object.

南面而坐,

北面而朝。

象憂亦憂,

象喜亦喜。

——打一用物

‘Very good!’ said Jia Zheng. ‘If the answer is “a mirror”, it is a very good riddle.’ 賈政道:好,好!如猜鏡子,妙極!

Bao-yu laughed: 寶玉笑回道:

‘That is the answer.’ 是。

‘Who is it by?’ said Jia Zheng. ‘There is no name on it.’ 賈政道:這一個卻無名字,是誰做的?

‘I expect that one is by Bao-yu,’ said Grandmother Jia. 賈母道:這個大約是寶玉做的?

Jia Zheng said nothing and passed on to the next one in silence. It was by Bao-chai: 賈政就不言語。往下再看寶釵的,道是:

My ‘eyes’ cannot see and I’m hollow inside.

When the lotuses surface, I’ll be by your side.

When the autumn leaves fall I shall bid you adieu,

For our marriage must end when the summer is through.

A useful object.

荷花出水喜相逢。

梧桐葉落分離別,

恩愛夫妻不到冬。

——打一用物。

Jia Zheng knew that the answer must be ‘a bamboo wife’, as they call those wickerwork cylinders which are put between the bedclothes in summertime to make them cooler; but a growing awareness that all the girls’ verses contained images of grief and loss was by now so much affecting him that he felt quite unable to go on. 賈政看完,心內自忖道:此物還倒有限,只是小小年紀,作此等言語,更覺不祥。

‘Enough is enough!’ he thought. ‘What can it be that makes these innocent young creatures all produce language that is so tragic and inauspicious? It is almost as if they were all destined to be unfortunate and short-lived and were unconsciously foretelling their destiny.’ The gloom into which this reflection plunged him was evident in the melancholy expression on his face and in his bowed and dejected stance. 看來皆非福壽之輩。想到此處,甚覺煩悶,大有悲戚之狀,只是垂頭沈思。

Grandmother Jia noticed it but attributed it to fatigue. She feared that in this melancholy mood his continued presence would place an even greater restraint on the young folk’s gaiety. 贾母见贾政如此光景,想到他身体劳乏,又恐拘束了他众姊妹,不得高兴玩耍,

‘I think you really oughtn’t to stay,’ she said. ‘Why don’t you go and lie down? The rest of us will sit up for a bit, but I don’t expect we shall go on very much longer.’ 便对贾 政道:你竟不必在这里了,歇着去罢。让我们再坐一会子,也就散了。

‘Yes,’ said Jia Zheng, roused from his reverie by her voice. ‘Yes, of course.’ 賈政一聞此言,連忙答應幾個 ‘是’,

But he forced himself to resume his former jovial manner and to drink another cup or two of wine with her before finally retiring. Back in his own apartment, he became lost in reverie once more; but whichever direction his thoughts took him in, he remained melancholy and troubled. 又勉強勸了賈母一回酒,方才退出去了。回至房中,只是思索,翻來覆去,甚覺淒惋。

Meanwhile the party he had just left was proceeding somewhat differently.

‘Now, my dears, you can enjoy yourselves!’ Grandmother Jia said as soon as he had left the room; and the words were no sooner out of her mouth than Bao-yu leaped up from his seat and over to the screen and began criticizing the riddles on it — this one had a line wrong here — that one’s words didn’t suit the subject — pointing with his finger and capering about for all the world like a captive monkey that had just been let off its chain. 這裡賈母見賈政去了,便道:你們樂一樂罷。一語未了,只見寶玉跑至圍屏燈前,指手畫腳,信口批評:這個這一句不好。那個破的不恰當。如同開了鎖的猴兒一般。

‘Can’t we sit down and enjoy ourselves quietly, as we were doing just now,’ said Dai-yu, ‘instead of all this prancing about?’ 黛玉便道:還像方才大家坐著,說說笑笑,豈不斯文些兒?

Xi-feng put in a word too, emerging from the inner room to say it: 鳳姐自裏間忙出來,插口說道:

‘You ought to have Uncle Zheng with you every day and never budge an inch from his side!’ She turned to the others: ‘What a pity I didn’t think of it at the time: we ought to have got Uncle to make him compose some more riddles for us. Then we should have seen him sweat!’ 你這個人,就該老爺每日令你寸步不離方好。適才我忘了,為什麼不當著老爺,攛掇叫你也作詩謎兒。這會子不怕你不出汗呢!

Bao-yu was greatly exasperated by this remark and tried to seize hold of her. Xi-feng tried to ward him off, and the result was that the two of them became locked in a sort of playful wrestling-match. 說的寶玉急了,扯著鳳姐兒,廝纏了一會。

Grandmother Jia continued for a while to laugh and joke with Li Wan and the girls, but soon began to feel tired and sleepy. The night-drum was sounding, and when they stopped to listen they found it was already the beginning of the fourth watch. She ordered the food to be cleared away, telling the servants that they might have what was left over for themselves. 賈母又與李宮裁並眾姊妹說笑了一會,也覺有些困倦起來。聽了聽已交四鼓了,因命將食物撤去,賞給眾人,隨起身道:

‘Time for bed, children!’ she said, rising to her feet. ‘We can do this again tomorrow, if you like; but now we must have some sleep.’ 我們安歇罷。明日還是節下,該當早起。明日晚間再玩罷。

With that the party gradually broke up and they all dispersed to their rooms. 於是眾人方慢慢的散去。[4]

For those who have read this far, we include in conclusion two lists of riddles:

- First, anodyne lantern conundrums complied in the People’s Republic for the 2017 Dingyou Year of the Rooster, see here; and,

- Second, for those with a more lascivious bent of mind, and taste in language, there are a number of online collectanea of ‘yellow’ 黄色, or more accurately ‘off colour’ riddles. For example:

瘸子屁股 ——打一俗語

脫衣好迎客 ——一成語

女人撐高 ——打一髮明家

永遠的處女 ——世界著名畫家邪(斜)門兒

寬以待人

畢昇

畢加索 (B加鎖)

To read more like this, see here.

Notes

[1] The line ‘He wants to climb the heavens to inspect the shining moon’ comes from ‘A Farewell Dinner for My Uncle Li Yun, the Collator, at Xie Tiao’s Tower in Xuan Prefecture’ 宣州謝朓樓餞別校書叔 by Li Bo. The full poem, as translated by Elling Eide and quoted in John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, eds, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume 1: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, New York: Columbia University Press, 2000, pp.735-736, reads:

That which has forsaken me,

the days that were yesterday and could not be detained.

That which has confounded me,

the day that is today full of trouble and woe.

A long wind sends the autumn goose

across ten thousand miles,

Faced with this it is only right to get tipsy upon a tower.

Patterns out of Penglai, the style of Jian-an times,

Along the way, with Little Xie,

they came forth fresh and clear.

Full of soaring inspiration, man’s heroic thoughts will fly;

He wants to climb the heavens to inspect the shining moon.

Draw a knife to cut the water, the water still flows on;

Raise a cup to banish grief, is grief the more.

When a man’s life within this world does not satisfy,

Let him at dawn leave down his hair

and push his boat from the shore.

棄我去者,昨日之日不可留;

亂我心者,今日之日多煩憂。

長風萬里送秋雁,對此可以酣高樓。

蓬萊文章建安骨,中間小謝又清發。

俱懷逸興壯思飛,欲上青天覽明月。

抽刀斷水水更流,舉杯消愁愁更愁。

人生在世不稱意,明朝散髮弄扁舟。

Mao Zedong would also use Li Bo’s line in his 1965 poem Reascending Chinkangshan — to the tune of Shui Tiao Keh Tou 水調歌頭 · 重上井岡山.

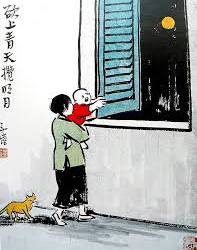

[2] This painting ‘The Moon Hangs from the Willow Branch’ is inspired by a poem about the Yuanxiao Festival by Ouyang Xiu 歐陽修 of the Song dynasty:

生查子 · 元夕

去年元夜時,花市燈如晝。

月到[上]柳梢頭,人約黃昏後。

今年元夜時,月與燈依舊。

不見去年人,淚濕春衫袖。

[3] This material is based on Geremie R. Barmé, An Artistic Exile, a life of Feng Zikai (1897-1975), Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, pp.24, 223 and 232-233, with minor modification.

[4] The Story of the Stone: A Chinese Novel by Cao Xueqin in Five Volumes, Volume 1, The Golden Days, translated by David Hawkes, pp.443-451. The Chinese text has been added and is based on Fan Shengyu’s 范聖宇 collated bilingual version of the novel published in 2012 by Shanghai Foreign Language Education Press, pp.528-539. For more Lantern Riddles and dark portents see Chapter 50, ‘Linked verse in Snowy Rushes Retreat; And lantern riddles in the Spring In Winter Room’ 蘆雪廣爭聯即景詩 暖香塢雅制春燈謎, The Story of the Stone, Volume 2: The Crab-flower Club, pp.508-511. See also the translator’s Appendix III to Volume 2, ‘Unsolved Riddles’, pp.588-594.