Hong Kong Apostasy

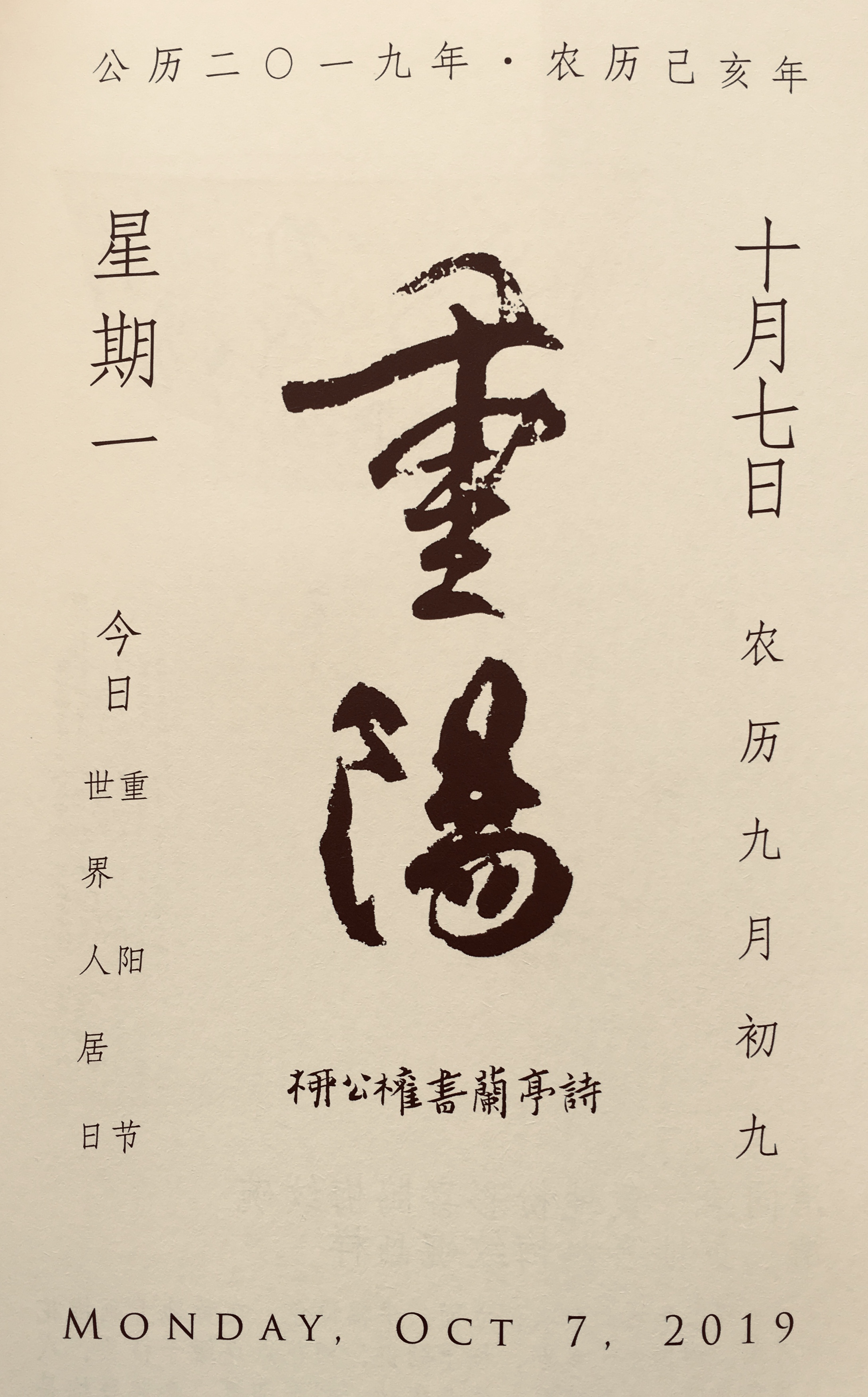

The 7th of October 2019 is the Ninth Day of the Ninth Month of the Lunar Calendar, a day that marks the Double Ninth Festival. In ‘New Sinology Jottings’ 後漢學劄記 we previously noted that the Double Ninth or Double Brightness Festival 重陽節 is a celebration of the autumn, a time of late bounty, seasonal change, lingering beauty and finality. It is also a time of encroaching darkness and death; a season during which old scores are settled.

This chapter in ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’ is included both in ‘The Best China’ and in ‘New Sinology Jottings’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

Ninth Day of the Ninth Month

Jihai Year of the Pig

己亥豬年九月初九重陽節

7 October 2019

***

Further Reading:

- Cao Xueqin and The Story of the Stone, China Heritage

- John Minford, David Hawkes (1923-2009) and the Translation of The Story of the Stone, The Wairarapa Talks

- Lee Yee 李怡 & To Kit 陶傑, ‘China, The Man-Child of Asia’, China Heritage, 26 September 2019

***

Deathly Air

The Double Ninth is the autumnal counterpart to the Qingming Festival on the Eighth Day of the Third Month (see In the Shade 庇蔭) which, apart from the commemoration of ancestors and sweeping of family graves, is also celebrated with spring outings (called 郊遊 or 踏青).

Now, in the autumn once more it is time to climb a height to enjoy the spectacle of the season, to mark the passage of time with relatives and friends and to enjoy the fruits of the season, including dogwood berries 茱萸 and chrysanthemums 菊花, the petals of which were traditionally macerated in wine to encourage longevity (or at least to help numb the pain of existence); moreover, ‘nine’ 九 is a homophone for ‘long’ or ‘continuous’ 久. This is why the day is related to longevity and the agèd; it is also known as the Chrysanthemum Festival 菊花節.

The autumn also signifies decline and the approach of winter, the end of the year. In dynastic China executions — referred to in the expression ‘beheadings following autumn’ 秋後問斬 — were carried out as the season came to an end and winter approached; it was literally a time suffused with death 肅殺之氣. In North China, with only one growing season that concluded with the autumn harvest, it was time to settle debts, or to seek a reckoning for perceived slights and injustices. The practice is neatly summed up in the expression 秋後算賬, ‘to settle scores after autumn [harvest]’.

Settling scores has also been a major feature of Chinese revolutionary life. It was the case with the violent failure of the Autumn Harvest Uprising 秋收起義 in 1927 when landlords and local officials were murdered, and, in recent times, since Communist Party congresses are convened in October, it remains so today. Each congress sees byzantine behind-the-scenes maneuvering and cloaked political payback.

In Hong Kong in 2019, the tone for the autumnal season of reckoning was set by the imposition on 5 October of a Prohibition on Face Covering Regulation (see Alan Leong Kah-kit, ‘Hong Kong’s Mask Ban Reveals Carrie Lam’s True Face’, the New York Times, 7 October 2019).

***

Fleeing The Qin 避秦

The recluse-poet Tao Yuanming (陶淵明, 365?–427 CE) has long been celebrated for his association with the chrysanthemum. A number of his poems are among the most often quoted, and over-interpreted, on the subject in the literary tradition. Famed for having given up service to the state for a life of leisure, writing, drinking, and occasional agricultural pursuits, Tao Yuanming is the archetype of a man who has rejected the onerous demands of the day to pursue instead the cultivation of the self. This quest for quietude, one also tinged with worldly concerns and fears, is recorded in poems that, for over 1600 years, have inspired artists and writers alike.

***

***

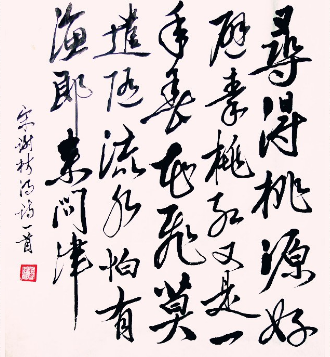

One of Tao Yuanming’s most famous essays is ‘Record of the Peach Blossom Spring’ 桃花源記, an account about a place untrammeled by the cruel uncertainties of the outside world. The narrator, an accidental visitor to the rural idyll, learns that the people there had ‘Fled The Qin and the Disorders of the Time’ 避秦時亂:

…There was a small opening in the mountain, and it seemed as though light was coming through it. The fisherman left his boat and entered the cave, which at first was extremely narrow, barely admitting his body; after a few dozen steps it suddenly opened out onto a broad and level plain where well-built houses were surrounded by rich fields and pretty ponds. Mulberry, bamboos and other trees and plants grew there, and criss-cross paths skirted the fields. The sounds of cocks crowing and dogs barking could be heard from one courtyard to the next. Men and women were coming and going about their work in the fields. The clothes they wore were like those of ordinary people. Old men and boys were carefree and happy.

… 林盡水源,便得一山,山有小口,彷彿若有光。便捨船,從口入。初極狹,才通人。復行數十步,豁然開朗。土地平曠,屋舍儼然,有良田美池桑竹之屬。阡陌交通,雞犬相聞。其中往來種作,男女衣著,悉如外人。黃發垂髫,並怡然自樂。

When they caught sight of the fisherman, they asked in surprise how he had got there. The fisherman told the whole story, and was invited to go to their house, where he was served wine while they killed a chicken for a feast, When the other villagers heard about the fisherman’s arrival they all came to pay him a visit. They told him that their ancestors had fled the disorders of Qin times and, having taken refuge here with wives and children and neighbors, had never ventured out again; they had lost all contact with the outside world. They asked what the present ruling dynasty was, for they had never heard of the Han, let alone the Wei and the Jin. They sighed unhappily as the fisherman enumerated the dynasties one by one and recounted the vicissitudes of each. The visitors all asked him to come to their houses in turn, and at every house he had wine and food. He stayed several days. As he was about to go away, the people said,

‘There’s no need to mention our existence to outsiders.’

見漁人,乃大驚,問所從來。具答之。便要還家,設酒殺雞作食。村中聞有此人,咸來問訊。自云先世避秦時亂,率妻子邑人來此絕境,不復出焉,遂與外人間隔。問今是何世,乃不知有漢,無論魏晉。此人一一為具言所聞,皆嘆惋。余人各復延至其家,皆出酒食。停數日,辭去。此中人語雲:不足為外人道也。

— translated by J.R. Hightower, in Minford and Lau, eds,

Classical Chinese Literature, vol. I, 2000, pp.515-516

As Lee Yee 李怡, whose work has featured prominently in our series ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’, observed in his essay ‘Back in the Year 當年’:

Most Hong Kong people came to this place to escape tyranny on the Mainland. Many just wanted a place where they could enjoy the ‘Freedom From Fear’. Over time, the British system with its traditions and protections instilled in Hong Kong people a belief that freedom and the rule of law were a natural state of affairs, something that was theirs to enjoy without them having to exert any particular effort. They had grown so accustomed to this environment that it seemed as natural as breathing the air around us; they did not give it a second thought. It simply was; it was a given; it wasn’t something for which you had to fight.

[Translator’s Note: ‘to escape tyranny on the Mainland’ is our translation of 避秦, literally, ‘to flee The Qin’. In his depiction of an idyllic world of peace and contentment, the fourth-century writer Tao Yuanming said that people had come to the Peach Blossom Spring ‘to flee The Qin’, that is, they sought (and found) a refuge from the harsh rule of the Qin dynasty and its infamous First Emperor 秦始皇, a figure to whom Mao Zedong compared himself favourably.]

— from Lee Yee, ‘Back in the Year — Hong Kong 1984’,

China Heritage, 31 July 2019

‘Fleeing The Qin and the Disorders of the Time’ 避秦時亂 was only possible because a safe haven existed, even though Hong Kong at best was a deeply flawed Peach Blossom Spring. The 2019 uprising was the latest, and most furious, response to the relentless advance of the autocratic northern regime from which people had sought refuge for generations.

Crabs as Metaphor 以蟹為喻 in

The Story of the Stone

As we noted in our previous essay on The Double Brightness Festival, the inhabitants of Prospect Garden in Cao Xueqin’s novel The Story of the Stone (石頭記 also known as The Dream of Red Mansions 紅樓夢) founded a poetry society called the Crab-Flower Club 海棠詩社, the members of which are named after the buildings which they occupy in the garden. Our colleague, the Stone scholar Annie Ren, selected two episodes from chapters Thirty-seven and Thirty-eight of the novel to illustrate our discussion of chrysanthemums during the festival, and we quoted the inspired English translation of the relevant passages by David Hawkes in The Story of the Stone, Volume II: The Crab-flower Club.

Following the poetic contest over chrysanthemums, the novel’s protagonists set to writing poems on the theme of Eating Crabs 詠蟹詩, another delight of the season. Two of their compositions in particular — those by Lin Daiyu 林黛玉 and Xue Baochai 薛寶釵, Lin’s rival for the affections of Jia Bayou 賈寶玉 — reveal aspects of the complex psychology of, and the underlying tensions between, the two young women.

In ‘To Kit’s Lectures on Literature’ 語文陶話廊 produced by CUP Media and available on YouTube, the noted Hong Kong essayist, cultural commentator and political analyst To Kit (陶傑, 1958-) offers an engaging contemporary interpretation of those famous Crab Poems. As the introduction to To’s talk states:

There is no need for students of classical Chinese literature to focus on matters that appear impossibly divorced from lived reality; indeed, much in the tradition is within easy reach. As the autumn winds swirl around us, To Kit uses the two Crab Poems from The Story of the Stone to discuss the vastly different world views of adherents of the pro-Beijing versus non-Beijing groups in Hong Kong today.

學古文的題目,不一定要離生活千百萬丈,也可以就地取材。在秋風起的日子,陶傑以「紅樓夢」中兩首「螃蟹詠」,分別說出建制和非建制兩種不同的人生態度。

Indeed, in his talk To draws in his young listeners by analysing the poems not only merely in terms of the repressed desires of the lovelorn female protagonists of the novel, but also as a way of understanding their starkly different personalities and views of the world. The first poem is written by the passive-aggressive Lin Daiyu which, as To amusingly suggests, can also be seen to reflect the kind of stubborn rebelliousness of Young Hong Kong today; that is, it shares many things in common with the Yellow Ribbon 黃絲 protesters who, since the 2014 Umbrella Movement, have been at a standoff with the hardline Beijing-imposed rulers of their city.

The author of the second poem, Xue Baochai 薛寶釵, To argues, can be regarded as advocating a more conventional, even conservative, ‘crab agenda’. To Kit then suggests that Xue’s attitude is not all that dissimilar from the Blue Ribbon 藍絲 stick-in-the-muds who confront feisty Young Hong Kong.

To Kit’s analysis is made in Cantonese, the lingua franca of Hong Kong. A Standard Chinese version of his comments appear as a chyron at the bottom of the screen:

***

David Hawkes translates the passage discussed by To Kit in the following way:

Poems in Praise of Crabs 詠蟹詩

Cao Xueqin 曹雪芹

Translated by David Hawkes

Discussion of the poems continued a little longer, after which they called for another lot of hot crabs and sat down at the large round table to eat them.

‘Eating crab-and admiring the cassia like this is itself a good theme for a poem,’ said Bao-yu. ‘I’ve already thought of one. Is anyone else game to have a try ?’

He quickly washed his hands and taking up a brush, wrote down the poem he had thought of. The others then read what he had written:

How delightful to sit and a crab’s claw to chew

In the cassia shade — with some ginger-sauce, too

Old Grim-chops wants wine, though he’s got no inside,

And he walks never forwards, but all to one side.

The ‘yolks’ are so tasty, who cares if we’re ill!

Though our fingers we’ve washed, they are crab-scented still.

‘O crabs,’ Dong-po said (and his words I repeat)

‘You have not lived in vain if you’re so good to eat!’持螯更喜桂陰涼,潑醋擂姜興欲狂。

饕餮王孫應有酒,橫行公子卻無腸。

臍間積冷饞忘忌,指上沾腥洗尚香。

原為世人美口腹,坡仙曾笑一生忙。‘One could churn out that sort of poem by the dozen,’ said Dai-yu.

‘You’ve used up all your inspiration,’ said Bao-yu; ‘but instead of admitting that you can’t write any more, you make rude remarks about my poem!’

Dai-yu made no reply, but tilted her head back, lifted up her eyes, and for some minutes could be observed muttering softly to herself; then, picking a brush up, she wrote out the following poem rapidly and without hesitation:

In arms and in armour they met their sad fate.

How tempting they look now, piled up on a plate!

The white flesh is tasty, the pink flesh as well —

Both the white in the claws and the pink in the shell;

And we’re glad he’s an eight- not a four-legged beast

When there’s plenty of wine to enliven the feast.

So with crab let us honour the Double Ninth Day,

While chrysanthemums bloom ’neath the cassia’s spray.鐵甲長戈死未忘,堆盤色相喜先嘗。

螯封嫩玉雙雙滿,殼凸紅脂塊塊香。

多肉更憐卿八足,助情誰勸我千觴。

對斯佳品酬佳節,桂拂清風菊帶霜。

Bao-yu had read this and was just beginning to say how good he thought it was when Dai-yu impetuously tore it up and told one of the servants to take away the pieces and burn them.

‘It’s not as good as yours,’ she said. ‘It deserves to be burnt, Actually yours is very good — better even than the chrysanthemum ones. You ought to keep it to show people.’

‘I’ve thought of one too,’ said Bao-chai. ‘It was rather a struggle, so I’m afraid it won’t be very good; but I’ll write it down anyway for a laugh.’

Then she wrote down her poem, and the others read it.

With winecups in hand, as the autumn day ends,

And with watering mouths, we await our small friends.

A straightforward breed you are certainly not,

And the goodness inside you has all gone to pot —桂靄桐陰坐舉殤,長安涎口盼重陽。

眼前道路無經緯,皮裡春秋空黑黃。

There were cries of admiration at this point.

‘That’s a very neat bit of invective!’ said Bao-yu. ‘I can see I shall have to burn my poem now!’

They read on.

For your cold humours, ginger; to cut out your smell

We’ve got wine and chrysanthemum petals as well.

As you hiss in your pot, crabs, d’ye look back with pain

On that calm moonlit cove and the fields of fat grain?酒未敵腥還用菊,性防積冷定須姜。

於今落釜成何益,月浦空餘禾黍香。

When they had finished reading, all agreed that this was the definitive poem on the subject of eating crabs.

‘It’s the sign of a real talent,’ they said, ‘to be able to see a deeper, allegorical meaning in a frivolous subject — though the social satire is a trifle on the harsh side!’

Just then Patience arrived back in the Garden.

— from Chapter Thirty-eight

The Story of the Stone, vol. II

translated by David Hawkes

***