Watching China Watching (XXVIII)

It was at a Communist Party enclave northeast of Beijing in October 1996. The autumnal skies, as the cliché holds, ‘went on forever and the air shimmered’ 秋高氣爽. The Asia-Australia Institute of the University of New South Wales had organised a multi-day symposium with a group of official think-tank intellectuals and policy wonks. The discussion ranged over such topics as Australia-China relations, regional affairs and Chinese society and politics.

We convened at a luxurious compound belonging to the Beijing Municipal Party Committee near the Miyun Reservoir in Huairou County. This secure and discrete locale was known among cognoscenti as the place where eighteen months earlier — in April 1995 — while facing numerous charges of corruption the vice-mayor of Beijing Wang Baosen 王寶森 had blown his brains out. The scenic Mutianyu section of the Great Wall 慕田峪長城 snaked over the hills to the west and participants in the symposium would have an afternoon of freewheeling conversation as they gamboled along a Disney-fied section of the Wall.

Over all, the bilateral discussions were civil and restrained. Our side was led by Stephen FitzGerald, Australia’s first ambassador to the People’s Republic and founder of the Asia-Australian Institute; other participants included Larry Strange, Michael Wesley, Kevin Rudd, Laurie Brereton, Jessica Rudd and me. As was usual on such occasions, I made myself unpopular by discussing June the Fourth, human rights abuses and the ongoing persecution of Liu Xiaobo, among others (The Gate of Heavenly Peace, a documentary film about 4 June 1989 that I had worked on, had been released the previous year and at the time of the symposium it was screening to sell-out audiences in Hong Kong). Our hosts chided such quibbles and, when they countered by raising the deplorable treatment of Australia’s indigenous people, few on the Australian side could mount an effective counterargument. After all, it was only weeks since the xenophobe politician Pauline Hanson’s 15 September maiden speech to the Australian parliament: the spectre of White Australia and the politics of racial discrimination loomed over us. However, we were also aware that glib moral equivalency was not a sufficient excuse to silence concerns about the egregious human rights abuses in China touted by our hosts as necessary state policy.

(On the eve of a post-4 June parliamentary human rights delegation being sent by Australia to the People’s Republic in 1991, Steve had asked me to invite a number of China scholars to offer advice to the Federal Government. In briefing members of the delegation, led by Senator Chris Schacht, and the foreign minister, Gareth Evans, we suggested ever so politely that this appeared to be a conscience-salving bilateral ‘exercise’ that would, for the most part, do little more than help pave the way towards a normalisation in relations. The foreign minister was, as was so often the case, incandescent. The delegation was duly despatched, it carried out its mission with all due diligence and it dutifully presented a formal report to parliament. From 1997, an annual behind-closed-doors Australia-China ‘human rights dialogue’ was established; the farrago went on for two decades, right up to the Nineteenth Congress of the Communist Party in late 2017.)

One particular topic of the discussion stayed with me. It was related to the concern of successive Chinese regimes that predates the Christian era; something summed up in the shorthand expression 邊患, ‘borderland threats’ or ‘troublesome frontiers’. At the time, what I would later call a major ‘historical conciliation’ was taking place in the People’s Republic; the Communist party-state was recasting its revolutionary origins in terms of a national (and nationalist) revival (see here). The dynastic era, long excoriated, was now being woven into the narrative of modern China, and issues of long-term historical concern increasingly featured in contemporary policy debates. Ethnic issues and the restive borderlands of the west — Tibet and Xinjiang — were of particular importance. (As part of its ‘on-the-ground investigations’, the 1991 parliamentary human rights delegation mentioned above congratulated itself in particular on securing permission to ‘observe’ human rights issues in the Tibetan Autonomous Region.)

Our interlocutors observed that although restive Tibet featured prominently in the international media — in particular since the 1988 anti-Beijing demonstrations in Lhasa crushed by an upcoming regional party boss by the name of Hu Jintao — they argued that, given time, natural attrition would resolve the ‘Tibet Problem’. With the demise of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama and the selection and education of his successor on Chinese soil — something that would develop in tandem with the role of the party ordained Panchen Lama — Tibetans surely would moderate their religious yearnings and dreams of independence and, in due season, come to appreciate the material benefits guaranteed by their privileged inclusion in the Chinese Motherland.

The Uyghurs in Xinjiang were an entirely different matter. This ‘new territory’ 新疆, one only incorporated into the lands of the Qing-dynasty in the eighteenth century, had ethnic, religious and political loyalties stretching far beyond the territory of the People’s Republic. Its ethnic peoples, in particular the Uyghurs were and would remain for the foreseeable future China’s preeminent ‘borderland threat’ 邊患. (Sometimes the speakers on the Chinese side were pragmatic and relatively historically aware but, by turns, they also touted the official line that all of the territory claimed by the People’s Republic today is integral to some ahistorical, numinous, indivisible and eternal Chinese ‘Holy Land’ 自古以來神聖不可分割領土的一部分).

As I have written elsewhere, the 2008 Olympic Year not only required heightened surveillance in the Chinese capital, it also offered security agencies greater scope for the policing of troublesome individuals and groups, from dissidents to ‘ethnic splittists’ (see Contentious Friendship, China Heritage, 29 April 2018). In the lead-up to August 2008 I was reminded of those discussion near the Miyun Reservour in 1996. They came back into sharp focus when Qing-dynasty historians of my acquaintance spoke in agonised tones about their recent academic and policy-related encounters with upcoming ‘Young Turk’ scholars, people who favoured more radical solutions to the ‘borderland problems’ of Tibet and Xinjiang. Some among them even argued that the millennia-old problem of ‘disquiet on the periphery’ 邊患 must now be resolutely addressed by Beijing. Meaningful, long-term solutions would, they suggested, probably have to include policies favouring the sequestration of troublesome ethnics in reservations, as well as intensified re-education, surveillance and policing. In the essay below, the historian David Brophy discusses these issues and the international context of China’s present ‘Uyghur problem’.

***

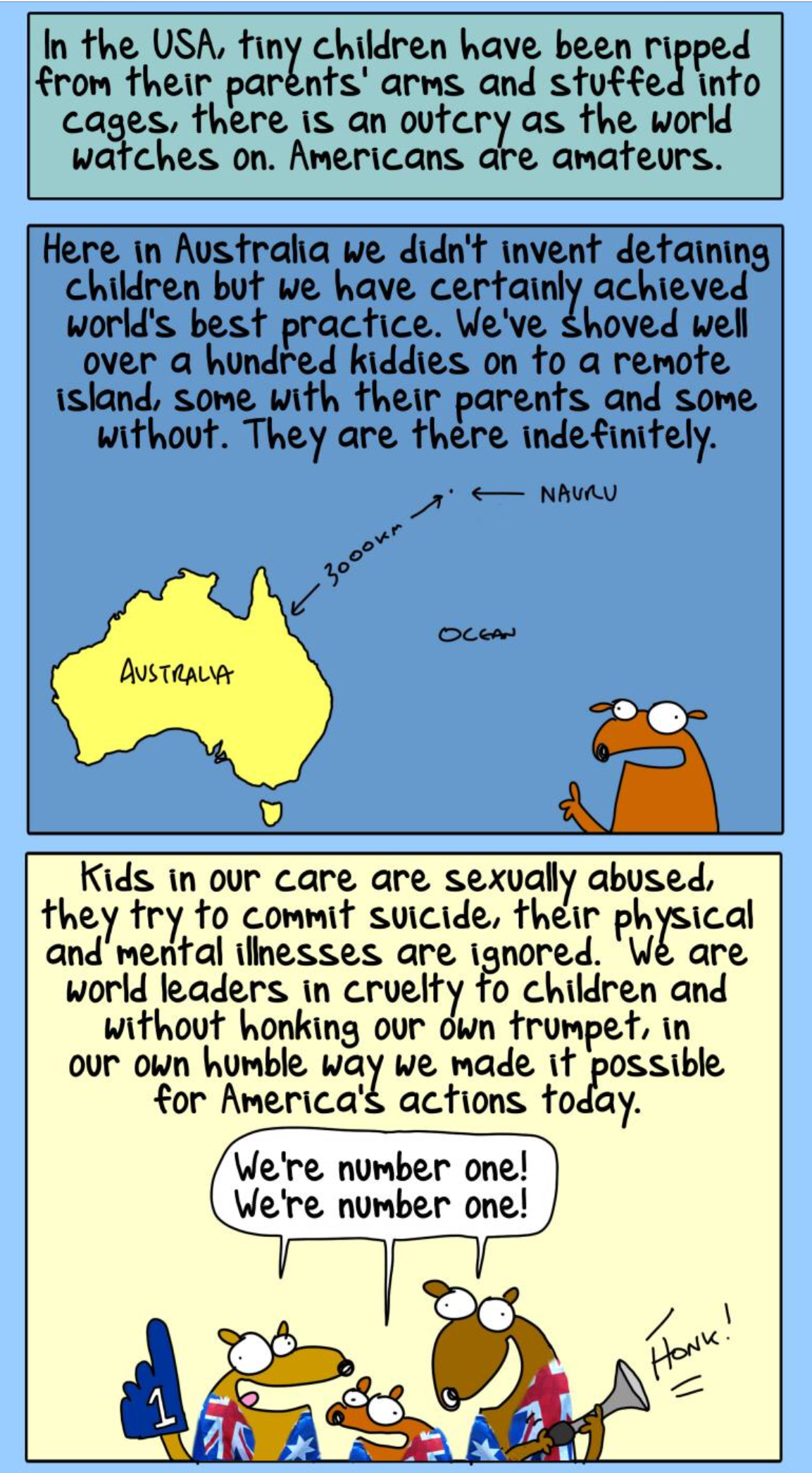

For our part, the Australian side in those October 1996 discussions had a mounting awareness of ‘borderland problems’ at home. In 1992, a strict new refugee policy had been introduced by Howard’s predecessor as Australian prime minister, Paul Keating. But in late 1996, few could imagine that the country would soon be ‘punching above its weight’ by developing tactics for repulsing and isolating the indigent, the desperate and the unwanted who sought hope in Australia (see First Dog on the Moon below).

The election of a conservative government under John Howard in March 1996 would see the revival not only of race-based politics, but also the devilish imposition of this expanded regime of homeland security, one later dubbed the Pacific Solution. This populist (and, it proved, election-winning) alarmist strategy advocated both the turning back of hapless refugees seeking asylum in Australia as well as the outsourced (that is, immensely expensive) sequestration of illegal arrivals on an isolated Pacific island in subhuman conditions. Along with these ‘policy solutions’ the government issued a diktat stating that undocumented arrivals would never be allowed to settle in Australia. A policy introduced by a conservative coalition over the years has been pursued by successor governments both right- and left-leaning.

A Humble Suggestion on

How to Deal with the Child Crisis

First Dog on the Moon

First Dog on the Moon, a celebrated Australian satirist, was quick to respond to the Trump administration’s manufactured border refugee crisis in the United States in May-June 2018. He pointed out both the avant-garde genius as well as the draconian efficacy of Australia’s off-shore internment regime. He chided Washington for its amateurish cruelty.

Inspired by Australia’s policy makers and taking a line from Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal (the full title of the 1792 tract is A Modest Proposal For preventing the Children of Poor People From being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For making them Beneficial to the Publick), First Dog offered the following:

For The First Dog’s full ‘humble suggestion’, see:

- First Dog on the Moon, A Humble Suggestion, The Guardian, 23 June 2018 (First Dog’s work also featured in an earlier essay by David Brophy. See Australia’s Asia, The China Story Journal, 31 October 2012)

***

Sixty Years Revisiting a Brave New World

In their propaganda today’s dictators rely for the most part on repetition, suppression and rationalization — the repetition of catchwords which they wish to be accepted as true, the suppression of facts which they wish to be ignored, the arousal and rationalization of passions which may be used in the interests of the Party or the State. As the art and science of manipulation come to be better understood, the dictators of the future will doubtless learn to combine these techniques with the non-stop distractions which, in the West, are now threatening to drown in a sea of irrelevance the rational propaganda essential to the maintenance of individual liberty and the survival of democratic institutions.

— Aldous Huxley, Brave New World Revisited, 1958

Why does what is happening today in China’s borderlands matter, and why link it to developments in the United States, Canada, Australia and Europe? Because such issues are not merely about one nation-state, but about the human, and political, dilemmas that confront everyone.

The People’s Republic of China fashions itself as a moral actor, a nation that champions rejigged traditional concepts such as the Rule by Virtue 德政, the Kingly Way 王道 and Humane Government 仁政. Through a panoply of hard politics and what I call Translated China (also known as ‘discourse management’), Beijing now advertises this style of judgement-laden Confucio-Marxist babble on the world stage while avowedly espousing a politics of non-interference.

As I have pointed out elsewhere (see Totalitarian Nostalgia), the New China Newspeak of Official China is a language suffused with moral-evaluative expressions that shape the way in which The China Story can be told (and thought about) both at home and abroad. As a nation of burgeoning economic and political heft, the People’s Republic has an exemplary impact on the global scene, as indeed the United States has had for many decades, be it for weal or bane. Just what that means in practice globally is a hotly contested topic (see, for example, The Battle Behind the Front, China Heritage, 25 September 2017); domestically for China the effects have been evident since the implementation of Patriotic Education indoctrination from the early 1990s and, even more so, from 2008.

In the wake of the March 2008 uprising in Tibetan China, for instance, although allowed continue operating lamaist monasteries have, in many cases, become a particular kind of state-monitored concentration camp for monastic communities: in them monks are isolated and subjected to constant surveillance and indoctrination while quite literally ‘chanting for their supper’ — permitted to pursue the religious life at the pleasure of the party-state while providing a dab of authentic local colour for the tourist industry. Exile at home and performative house-arrest are now features of China’s new frontiers of commercialised policing.

The taint or moral stain of complicity or agreement with egregious policies of racism, discrimination and xenophobia infects whole societies. It can incrementally transform and corrupt the notion of humanity itself. China’s today might not necessarily be our tomorrow, but for longer than many of us might like to think, we have been on the borderlands of this Brave New World.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

26 June 2018

Further Reading:

- Watching China Watching, China Heritage, 5 January 2018 –

- Sinopsis and Jichang Lulu, UN with Chinese Characteristics: Elite Capture and Discourse Management on a global scale, 25 June 2018 (reprinted by China Digital Times)

- Ann Kent, Between Freedom and Subsistence: China and Human Rights, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press, 1993

- Ann Kent, China, the United Nations, and Human Rights: The Limits of Compliance, Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999

- Geremie R. Barmé, Shared Values: a Sino-Australian conundrum, The China Story, 20 October 2015

Xinjiang, from The China Story Lexicon

In 2012, working with colleagues at the Australian Centre on China in the World (CIW) of which I was the founder, I launched The China Story Project 中國的故事 (for details, see Telling China Stories). The project consisted of a multi-facted website, including a frequently updated journal, a survey of Chinese intellectual life, an archive on Australia-China relations and an annual digest, The China Story Yearbook. In its early phase, the project also developed The China Story Lexicon.

The Lexicon featured keywords related to China and the long-term plan was to cover the major topics of popular, media and academic concern related to The China Story. Each Keyword would feature an overview of the topic in question, a survey of international scholarship as well as an introduction to the Official Chinese Story, the Academic Story in China, the Dissident View of the topic, Media Representations, as well as other relevant material. It seemed like a timely and important undertaking and we were able to publish a few entries before things fell into desuetude.

Xinjiang 新疆, an early entry in The China Story Lexicon, was developed by David Brophy, one of CIW’s inaugural postdoctoral fellows. David and I worked on this material in the hope that it would provide a model for future entries. It remains a useful reference guide. We re-present material from Xinjiang 新疆 here in order to frame a recent essay by David Brophy on the internment crisis in Xinjiang published by Jacobin Magazine. David is now a senior lecturer in modern Chinese history at The University of Sydney. He is the author of Uyghur Nation: Reform and Revolution on the Russia-China Frontier (2016).

— Geremie R. Barmé

***

Xinjiang 新疆

An Overview

David Brophy

Although not as well known outside China as the question of Tibet, the conflict over Xinjiang appears to be equally as intractable, and similarly grounded in conflicting accounts of both the past and the present.

Xinjiang is an autonomous region within the People’s Republic of China (PRC). Its immediate precursor was a product of the expansion of the Qing dynasty (1644-1912) during the eighteenth century. Xinjiang was transformed from being a dependency into an imperial province in the 1880s. It reverted to semi-independent warlord control for much of the Republican period (1912-1949), and was incorporated into the PRC by the People’s Liberation Army in 1950. At that time it was home to a large Uyghur majority, with smaller communities of other Central Asian peoples (e.g., Kazakh, Kirghiz, Mongols, Tajik), as well as Han and Hui migrants from Chinese provinces to its east. Recent immigration has seen a rapid rise in the Han Chinese population; factoring in the floating population of migrant workers, this population is now believed to exceed that of the Uyghurs.

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) dates from 1955. It comprises roughly one sixth of China’s total landmass, borders on eight neighbouring countries, and contains the largest remaining reserves of oil and gas thought to exist on Chinese soil.

Since the collapse of the Soviet Union and the declaration of a ‘War on Terror’ by the United States in 2001, Uyghur opposition has been cast by China as one wing of an international terrorist conspiracy. This manner of framing issues related to Xinjiang has helped China win endorsement for its definition of the internecine struggle in some circles. The presence of Uyghur militants in Pakistan and Afghanistan cannot be denied, however their numbers, level of organization, and their efficacy inside Xinjiang are all disputed both by Chinese and by foreign observers.

The mainstream leadership of the Uyghur diaspora has adapted to changing international conditions, eschewing talk of armed struggle and independence in favour of a human rights-based strategy. It now seeks support from governments and NGOs in Europe and the US. Recently, the emergence of Rebiya Kadeer (b.1948) has given greater unity to the fractious exile movement. Well known among Uyghurs inside and outside China, Rebiya was formerly a successful businesswoman in Xinjiang, before her detention as a political prisoner from 1999 to 2005.

On 5 July 2009, Uyghur protests in Ürümchi calling for an investigation into the beating death of Uyghur employees in a Guangzhou factory descended into bloody riots, resulting in the death of many Han Chinese, and leading to revenge attacks against Uyghurs (for more on this, see Anxieties in Tibet and Xinjiang, China Story Yearbook 2012).

Under the rubric of a ‘New Silk Road’, the PRC now projects a prosperous future for Xinjiang as a major transport hub and the dominant economic actor in Central Asia. From this official perspective, the ‘Xinjiang problem’ is a product of the main local ethnic group, the Uyghurs, claiming Xinjiang as an exclusive homeland, some advocating an independent Eastern Turkistan. Many Uyghurs feel deprived of genuine autonomy as well as being demographically threatened by Han migration from the interior; they are concerned about who will benefit in reality from increased investment in the region. Chinese official and broad-based social unease with the ‘Xinjiang problem’ is a result of a sense that despite the Beijing’s best efforts to encourage inter-ethnic harmony and development, local disquiet and rebellion continues.

— from David Brophy, Xinjiang 新疆

The China Story Lexicon, 2 August 2012

For the more material from The China Story Lexicon entry on Xinjiang, click on the following (also reproduced below):

Perspectives on Xinjiang

Sailing to Guantánamo

Detention in a handful of camp systems has been framed as protective, ostensibly guarding an unpopular group from public anger — and sometimes they really have offered protection. More commonly, detention is announced as preventative, to keep a suspect group from committing potential future crimes. Only rarely have governments publicly acknowledged the use of camps as deliberate punishment, more often promoting them as part of a civilizing mission to uplift supposedly inferior cultures and races. …

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt described concentration camps as divided into Purgatory, Hades, and Hell, moving from the netherland of internment to labor camps of the Gulag and Nazi death factories. But nearly all concentration camps share one feature: they extract people from one area to house them somewhere else. It sounds like a simple concept, but both elements are distinct and important. Camps require the removal of a population from a society with all its accompanying rights, relationships, and connections to humanity. This exclusion is followed by an involuntary assignment to some lesser condition or place, generally detention with other undesirables under armed guard. Of these afterworlds, Arendt writes,

“All three types have one thing in common: the human masses sealed off in them are treated as if they no longer existed, as if what happened to them were no longer of interest to anybody, as if they were already dead and some evil spirit gone mad were amusing himself by stopping them for a while between life and death.”

— from Andrea Pitzer, One Long Night:

A Global History of Concentration Camps,

New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2017

***

The following essay appeared under the title China’s Uyghur Repression in Jacobin on 31 May 2018. We are grateful to the author and to the editors of Jacobin for permission to reproduce it here as part of our series Watching China Watching.

— The Editor

China Heritage

Concentrating on Xinjiang

David Brophy

International attention on the question of Xinjiang, the autonomous region in the northwestern corner of China, and the oppression of its native Uyghur population by the Chinese state still lags behind the well-publicized case of Tibet. Yet in the mind of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Xinjiang, which many Uyghurs call East Turkistan, now outweighs Tibet as a policy priority.

In the name of combating Islamic extremism, the party has embarked on a massive campaign of detention and indoctrination of ethnic minorities. Its goal is to eradicate all possibility of opposition here once and for all and turn this huge territory into a stable platform from which to extend its Belt and Road Initiative and dominate Central Asia.

The emergence in Xinjiang of a new network of political reeducation camps has been a poorly kept secret for some time. But research and reporting is giving us hard evidence of the scale of this new policy. Since the middle of 2017, a major construction boom has thrown up a variety of detention centers and prisons whose inmates number in the hundreds of thousands. These camps combine many of the brute horrors of China’s earlier reeducation-through-labor system with the latest high-tech surveillance and monitoring mechanisms.

Without facing any charge, detainees (mostly Uyghurs, but some Kazakhs) find themselves cut off indefinitely from the outside world. Suspicion falls easily on those who display signs of excessive religious piety or have contacts abroad, but the sweep is much wider than this. Even speaking Chinese poorly seems enough to get you detained.

The most unfortunate find themselves subject to daily beatings and interrogations; the lucky ones endure a routine of self-criticism sessions and the mind-numbing repetition of patriotic slogans. Drumming out loyalties to religious faith and national identity features prominently in this curriculum.

The camps are only the culmination of a series of repressive policy innovations introduced by party secretary Chen Quanguo since his arrival in Xinjiang in 2016. Many of these were already evident on a trip I made to Xinjiang last year: police stations at every major intersection, ubiquitous checkpoints where Chinese sail through as Uyghurs line up for humiliating inspections, elderly men and women trudging through the streets on anti-terror drills, television and radio broadcasts haranguing the Uyghurs to love the party and blame themselves for their second-class status.

I saw machine gun-toting police stop young Uyghur men on the street to check their phones for mandatory government spyware. Some have simply ditched their smartphones, lest an “extremist” video clip or text message land them in prison. On a weekday in the Uyghur center of Kashgar, I stood and watched as the city went into lockdown, making way for divisions of PLA soldiers to march by, chanting out their determination to maintain “stability.”

More than at any point since its incorporation into the People’s Republic of China, Xinjiang today resembles occupied territory, and the party’s policies reveal an all-encompassing view of the Uyghurs as an internal enemy. The Uyghurs’ very presence in the land is an inconvenient reminder of Xinjiang’s alternative identity as the eastern fringe of the Islamic and Turkic-speaking world — one that Beijing would prefer to erase if it could. The party may not have any intention yet to physically remove the Uyghurs, but its efforts to marginalize the Uyghur language and rewrite the region’s history serve similar goals to a policy of ethnic cleansing.

Even for a region where actual ethnic relations have rarely lived up the harmonious scenes of party propaganda, this is a historic low point. How did a revolutionary state, which came to power promising to end all forms of national discrimination, end up resorting to such horrific policies? And what, if anything, can those of us outside China do to help turn things around?

An Imperial Frontier

The story of Beijing’s hold on Xinjiang begins in the 1750s, with a wave of imperial expansion during China’s last dynasty, the Qing. For more than a century, the empire’s Manchu and Mongol military caste exercised only a very indirect form of rule, one that was intermittently thrown off by local Muslim rebellions. Looking back, many Uyghur nationalists would point instead to the 1880s, when Xinjiang became a full-blown province of the empire, as the real starting point of Chinese colonialism. At this time, Chinese bureaucrats took up the reins of administration, and they clung on tight through the anti-Qing revolution of 1911–12.

Uyghurs made bids for self-rule during the Chinese Republic, from 1912 to 1949. In doing so they often sought some form of outside support. Unluckily for them, the only realistic source of such support was the Soviet Union.

In the 1920s, within the Comintern’s wider push for revolution in the Islamic world, the Bolsheviks flirted with the idea of turning Xinjiang into a Soviet Republic. But as the international revolutionary tide subsided, the Soviet Union’s own state interests in Asia came to dominate its approach to Xinjiang and prevented it from extending genuine solidarity to the Uyghurs.

In the 1930s, a large-scale revolt led to the creation of the Islamic Republic of East Turkistan in Kashgar, but Moscow preferred to side with Chinese rule and aided in crushing it. In the 1940s, Stalin gave the green light to an uprising in the west of the region, which created what is known as the Second East Turkistan Republic. This was a high point in the history of a secularist strand of Uyghur nationalism which had emerged in the Soviet Union, but Stalin’s only priority was to maintain economic and political dominance in the region. The republic was wound up when he cut a deal with Mao to allow the People’s Liberation Army to take control of Xinjiang in 1949.

By the time it reached Xinjiang in 1949, the CCP had set aside its commitment to national self-determination, offering only a diminished form of “national autonomy.” In selling this vision of a more centralized postrevolutionary China, the party had to purge those native Communists who were holding out for something more substantial like a Soviet Republic of Uyghuristan.

By the standards of the 1950s globally, the CCP’s nationality policies still had progressive aspects, among them a public renunciation of Han chauvinism, affirmative-action policies in education and employment, and the provision of native-language schooling through secondary level. Yet the party’s commitments to respecting national rights in Xinjiang often took a back seat to its development and security goals on what was still a sensitive geopolitical frontier. The Cultural Revolution helped to erode any good will toward the party that there might have been among the Uyghur population.

When a limited liberalization came in the 1980s, Uyghurs took advantage of the opportunity to test the boundaries of permissible discourse, with activists launching an embryonic student movement. By the end of the decade, though, advocates of moderation had lost the battle inside the party, and any narrow scope for organized Uyghur opposition was lost amid the nation-wide crackdown of 1989. Books were burned and prominent intellectuals jailed.

The retreat to hard-line policies was entrenched with the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, which some in the CCP leadership interpreted as a product of non-Russian nationalism on the Soviet periphery. Since that time, the only solution the party has had for Uyghur discontent has been to tighten its ideological control and engage in periodic “strike-hard” roundups.

In the wake of 9/11, China refashioned its hard-line campaign against separatism into a wing of the global “war on terror,” and in doing so reached something of an accommodation with Washington. There have been sporadic acts of terrorist violence in Xinjiang and elsewhere in China, some of which, tragically, have cost the lives of ordinary Han Chinese. But Uyghur resistance in Xinjiang is much more disorganized and demilitarized than China would like us to believe. China’s war on terror has claimed as its victims even mildly dissenting party members such as economics professor Ilham Tohti, who was given a lifelong prison sentence four years ago for criticizing the marginalization of Uyghurs in Xinjiang.

It is true that some desperate Uyghurs have found their way into the ranks of Islamist militias in Syria and Iraq, hoping to acquire the military training and international jihadist solidarity which they see as necessary for a fight in Xinjiang. But this dead-end strategy poses no threat to Beijing — and certainly not one that could justify today’s crackdown. China maintains a choke hold on Xinjiang’s entry and exit points; only the Chinese state benefits from the presence of Uyghur militants in this far-off battleground.

Many outsiders have drawn the conclusion that there is too little autonomy in the of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region: the center holds a veto on any local legislation, and provisions for cultural and linguistic rights have long been a dead letter. Yet party thinkers tend to embrace the opposite view: that the system gives minorities too much autonomy. In 2011-2012, debate arose on reforms to China’s official nationality system, with some floating the idea of abolishing autonomous regions, or even the nationality categories themselves. The proposals reflected what seems to be a widely held view in the CCP elite, that discontent is a function of the ideas in people’s heads, not policies on the ground. Change those ideas, therefore, and you change the situation.

The proposals were too iconoclastic for the party to endorse, but the approach in Xinjiang today reflects the same motivation: to end ethnic conflict by eradicating all space to make claims in the name of a Uyghur nation.

The Vicious Circle of Xinjiang Advocacy

The repression in Xinjiang is too intense to expect resistance to emerge to the new policies any time soon. Nor should we anticipate inner-party opposition to them in Beijing. Abroad, though, many ask what can be done to help the Uyghurs. The Uyghur diaspora has rallied around the world recently. Journalists and scholars have made admirable efforts to bring to light the disturbing realities.

And last month in Washington, Senator Marco Rubio brought the Uyghur question back into play in US China policy, by making a very public intervention surrounding the reeducation camps, pointing specifically to the detention of family members of Radio Free Asia journalists.

Some, possibly many Uyghurs, will welcome Rubio’s intervention. With good reason, they see themselves as victims of Communism, caught as they have been between two repressive mega-states that described themselves as Communist. Much of the international left long endorsed the idea that the Soviet Union and China were examples of living socialism, and therefore to be defended at all costs. Without any friends on the Left, Uyghurs in exile have naturally tended to gravitate towards the anticommunist right.

The tragedy is that this has made it all too easy for Beijing to portray Uyghur discontent as the product of a hostile Western conspiracy. This is opportunistic and cynical, but unfortunately, it is persuasive to some Chinese. There is a vicious circle here, one that only leads us away from a just solution in Xinjiang. And as the Xinjiang question comes to international prominence once again, it risks falling back into this familiar rut.

Foreign governments naturally shouldn’t hesitate to criticize China’s mistreatment of its minorities. But Rubio, predictably, went beyond this, in explicitly linking the plight of the Uyghurs to US objectives in Asia. Writing to the US ambassador in Beijing, he asked him to look into the issue because the “crackdown in the XUAR touches on a range of interests critical to US efforts to secure a free and open Indo-Pacific region.”

Rubio is now spearheading an effort to ramp-up pressure on China across the board, a push that follows on the heels of Washington’s most hawkish foreign-policy statements on China since it officially recognized the People’s Republic in 1979.

In the wider debate surrounding China’s rise, some traditionally progressive voices now believe we have no choice but to set aside our “knee-jerk anti-Americanism” and embrace US global dominance. So objectionable is China’s authoritarian system, they argue, that as its weight increases in world affairs, we must unite to resist it.

But Western saber-rattling will not help anyone in Xinjiang. Linking the injustices there directly to Washington’s bid to shore up a declining hegemony in Asia will only strengthen the party’s resolve to clamp down, meaning that Xinjiang’s reeducation camps could very quickly turn into internment camps for the entire Uyghur population. It’s unthinkable what an actual war might bring.

Meanwhile, some on the Left might be tempted to take the opposite approach: to go quiet on China’s domestic policies and focus instead on combatting our own militaristic tendencies. But to drop any criticism of China would be to shirk a moral responsibility to speak out against oppression and a political responsibility to find solutions to it. Progressive acquiesce to the right-wing monopoly on the discourse around Xinjiang is one of the reasons we got into this vicious circle in the first place; we need to look for a way out of it.

An Alternative Approach

Most people coming to the Xinjiang question would sit somewhere between these positions of nothing but support for the US and nothing but criticism of it. Sure, Rubio’s belligerence carries its risks, you might say, but at least he’s saying the right thing about the Uyghurs.

But it’s not enough to simply criticize right-wing politicians when they get things wrong and applaud them when they get things right. We need to actively decouple the Xinjiang issue from the pursuit of Western interests in Asia, and provide it with a different framing, one that speaks in universal terms of a rejection of racism and discrimination.

It’s not just that a drive toward war will only make things worse for the Uyghurs or that being morally consistent is a good thing to do. There are pressing practical reasons why such an approach is necessary.

There’s no point talking about holding China to international norms when those norms don’t exist. If anything, Islamophobic bigotry has become the norm around the world, and with it a variety of intrusive and punitive de-radicalization programs similar in conception, if not scale, to China’s. Reading Jim Wolfreys’s recent book on France, it’s not hard to see similarities with the measures being implemented in Xinjiang: bans on forms of veiling, citizens encouraged to look out for signs of radicalization as innocuous as someone changing their eating habits. In 2015, Socialist Prime Minister Manuel Valls went so far as to consult on the constitutionality of creating detention centers for more than ten thousand people on a police watch list of suspected extremists.

This globalizing Islamophobia has dealt Uyghurs a double blow. Almost all Muslims themselves, they experience it when living in the West. It makes it more difficult for them to claim asylum and start a new, normal life outside China. But it also provides the ideal international environment for China to carry out its repression in Xinjiang.

Western leaders have no more qualms about treating Muslims as terrorists than Chinese officials in Xinjiang. This is the principle that informs Donald Trump’s Muslim ban, a policy he is still fighting for in the US courts. And it lies at the heart of Israel’s defense of its massacre in Gaza, an outrageous alibi that Trump and Australian Prime Minister Malcom Turnbull have both endorsed on the world stage. People speaking up for the Uyghurs need to take a strong stand against the dehumanizing treatment of Muslims by the West and its allies.

This approach also gives us an opening with an important constituency on this question — ordinary Han Chinese citizens of the People’s Republic of China. Migration from the interior has brought Xinjiang’s Chinese population close to parity with that of its indigenous Uyghurs, meaning that any struggle — be it for independence, greater autonomy, or simply equal rights — must of necessity draw on Chinese support. And while it’s hard for us to talk to Chinese in Xinjiang, we can talk to those in the West.

Many of these PRC citizens have mixed feelings about an issue like Xinjiang: they recognize that CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping might be heavy-handed but think he’s right about Western meddling in China’s affairs. And while acknowledging its flaws, they credit the growing strength of the party-state with reducing the amount of old-style Sinophobia they experience when they go abroad. To persuade these people to share our outrage towards the situation in Xinjiang, we have to make a convincing case to them that this outrage reflects a commitment to anti-racism and justice for all, not a campaign to undermine China.

Right now, our ability to do this is threatened by the West’s confrontational stance towards China, which borrows much from the PRC’s own paranoid view of ethnic minorities as inherently dangerous. The scare campaign surrounding Chinese interference in Western democracy has led security agencies to depict the entire Chinese immigrant community as an internal enemy of our own. Going down this path will close off the possibility of engaging with ordinary Chinese on a sensitive topic like Xinjiang.

It’s a huge ask to expect anyone from China to stand up against the racism and discrimination that exists in their community. If we’re going to ask Chinese to do that, we have to show them that we’re willing to do the same ourselves. As a US-China confrontation looms, those speaking up for the Uyghurs in China should be ready to do the same for Chinese being victimized in the West.

Obviously, turning this stance into a convincing, practical political alternative will require real work. It won’t be easy to build up a progressive alliance around the question of Xinjiang with enough weight to rival the resources and influence of the anti-China hawks. For the time being, some Uyghurs will be heartened by Washington’s tough talk against Beijing. But they also know, from bitter experience, that foreign governments who take up this issue can just as quickly drop it if their priorities shift elsewhere. That’s all the more reason to craft an approach that won’t be vulnerable to the political winds in Washington.

The defense of Chinese minorities’ rights must go hand in hand with a firm antiwar stance on Western foreign policy, a determination to end Islamophobia, and vigilance toward anti-Chinese prejudice in our own communities. Linking the question of Xinjiang to these causes is not a distraction; it’s an opportunity.

Recommended Reading:

- David Brophy, The Past and Present of Inner Asian Studies, An Australian Centre on China in the World Research Theme Workshop, 23-24 March 2012, China Heritage Quarterly, Nos. 30/31 (June/September 2012)

- David Brophy, Australia’s Asia, The China Story Journal, 31 October 2012

- David Brophy, Little Apples in Xinjiang, The China Story, 16 February 2015

- Adrian Zenz and James Leibold, Chen Quanguo: The Strongman Behind Beijing’s Securitization Strategy in Tibet and Xinjiang, China Brief, 17.12 (21 September 2017)

- Andrea Pitzer, One Long Night: a global history of concentration camps, New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2017

- Andrea Pitzer, Harbingers and Echoes of the Shoah: A Century of Concentration Camps, Cornell University video lecture, 6 November 2017

- Tom Cliff, When Not to Respect Your Elders, China Story Yearbook 2017: Prosperity 富, Jane Golley and Linda Jaivin, eds, Canberra: CIW and ANU Press, 2018, pp.64-69

- How should the world respond to increasing repression in Xinjiang?, ChinaFile, 4 June 2018

- James Leibold, Time to Denounce China’s Muslim Gulag, The Lowy Interpreter, 19 June 2018

- First Dog on the Moon cartoons

Xinjiang 新疆

The China Story Lexicon, continued

David Brophy

The Official Chinese View

China’s constitution prescribes equality for all before the law, provides effective checks against ethnic discrimination, and guarantees religious freedom for all faiths. To quote from a recent statement on ethnic policy, the cornerstones of China’s approach to Xinjiang are ‘equality, unity, regional ethnic autonomy, and common prosperity for all ethnic groups.’ Thus, Chinese officials deny any link between local discontent and prevailing ethnic and religious policies.

In the wake of the July 2009 riots, the body charged with such matters, the State Ethnic Affairs Commission, stated that: ‘[t]he riots were not because of ethnic policies and they were not related to any religion either’ (Global Times). Instead, such opposition is attributed to outside agitation stirred up by groups and governments that seek to exploit gullible Uyghurs with the aim of destabilizing China and frustrating the nation’s global rise.

Despite superficial differences, Islamic terrorism and Western human rights discourse are in fact two sides of the same coin. Western expressions of concern for the ‘oppressed’ Uyghurs amount to sympathy for violent acts of terrorism. They are a cover for a concerted long-term strategy that would see China enfeebled. [Watching America] [Global Times]

History

China bases its claim to Xinjiang on history and an argument that says the territory has been an inalienable part of China from early dynastic times. Today, in the PRC it is required that works on Xinjiang’s history, official documents and media reports reiterate the point that Xinjiang is an integral part of China. The Chinese party-state regards an ‘objective’ or ‘correct’ understanding of Xinjiang’s history, that is the official viewpoint on all matters to do with the past and present state of the region, to be essential to the region’s harmonious development.

One of the most visible responses to the 2009 Ürümchi riots is the 2010-2011 ‘Three Histories’ education campaign. This region wide re-education movement saw lectures given on:

- the history of Xinjiang 新疆史;

- the history of the development of ethnic minorities 民族发展史; and,

- the history of the evolution of religions 宗教演变史.

A summary of the official view of Xinjiang’s history can be found in the White Paper on the History and Development of Xinjiang, released in 2003. In that document it is claimed that ’since the Han Dynasty established the Western Regions Frontier Command in Xinjiang in 60BCE, the Chinese central governments of all historical periods exercised military and administrative jurisdiction over Xinjiang.’

Nowhere in its justifications for ruling Xinjiang does the Chinese state refer to an act of conquest. The Qing dynasty’s incorporation of the territory in the eighteenth century is described in present Chinese works as a ‘re-unification’ 统一, or as a ‘recovery’ 收复 of a temporarily alienated territory. The Qing rulers were less committed to the notion of a primordial state of Chinese unity; they called the territory ‘New Frontier’ or ‘New Borderlands’ 新疆 — a designation that reflects its recent incorporation. The Qing referred to its enemies as ‘bandits’, and its own actions as being that of ‘subduing and pacifying’.

Contemporary Chinese official discourse now elaborates on this terminology to describe Qing victories as being the suppression of Mongol or Muslim ‘rebellions’, and it anachronistically applies terms such as ‘separatist’ to describe the motivations of independent Mongol chiefs in centuries past. Conversely, acts of submission to the Qing are regarded as evidence of patriotic sentiment towards China.

While recognising the errors of Nationalist (KMT; Guomindang) assimilationist policies during the Chinese Republic, aspirations that emerged at this time for an independent Eastern Turkistan 东突 are primarily seen as being the product of colonialist manipulation. The first Eastern Turkistan Republic (1933) is dismissed as illegitimate 伪. The second Eastern Turkistan Republic (1944-1949), however, was described by Mao Zedong as an important contribution to Xinjiang’s liberation from the Guomindang. Therefore today it is grudgingly endorsed, although the name ‘Eastern Turkistan Republic’ is avoided in favour of the more modest ‘Three Districts Revolution’ 三区革命.

The incorporation of Xinjiang into the PRC in 1950 came in the form of ‘peaceful liberation’ 和平解放. This does not mean that there was no violence – the People’s Liberation Army fought campaigns against local ‘bandits’ – but that the Communist forces did not have to fight the Nationalists for control. Xinjiang was initially ruled by a military command. In 1954, drawing on a long history of military colonization in China’s west, the PLA founded the Xinjiang Construction and Production Corps, a network of industrial and agricultural outposts that still occupies an important position in Xinjiang’s economy.

Ethnicity

The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region was founded in 1955. Levels of autonomy are enjoyed by all the ethnic groups of the region through a system of ‘nested autonomy’. Usually, local government bodies are headed by a non-Han, but with a Han party chief by his/her side. The system of autonomy was only codified in 1984 with the passing of The Regional Ethnic Autonomy Law [See also here]. Coming on the heels of the then Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang’s call for the ‘ethnicization’ (minzuhua 民族化) of minority regions, this legislation protects minority language and culture, and provides for a minimum level of self government (although these provisions were weakened in 2001). The law contains few concrete prescriptions and certain policies originally designed to safeguard minority languages and cultures are now seen as being barriers to integration. Uyghur-language schooling, for example, is being replaced by ‘bilingual education’, which envisages the introduction of Standard Chinese from the pre-school level.

Today: the ‘Three Inimical Forces’

Threats to Xinjiang’s stability continue to arise from the ‘Three Forces’ 三股势力, namely separatism, religious extremism, and international terrorism. Sometimes rendered in English as the ‘Three Evils’, this formulation was introduced in 2000 during meetings of the Shanghai Five, a group that evolved into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization. The 11 September 2001 attacks and the US ‘War on Terror’ let China present itself as being a victim of Islamic terrorism; subsequently, Uyghur organisations based in Afghanistan and Pakistan were listed as terrorist groups. Despite this, Chinese law stipulated no definition of terrorism until 2011, when a draft was put forward by the National People’s Congress, China’s parliament.

The best response to these threats is to increase the pace of development. High-level Party meetings held in 2010 unveiled a ‘roadmap’ to prosperity for Xinjiang, aiming to transform it into a ‘moderately prosperous society’ 小康社会 by 2020. Measures towards this objective include large construction projects, such as gas and oil pipelines to the east, and a new resource tax designed to boost local government revenues. Other recent policy innovations include a program twinning Xinjiang towns with richer cities of the coast, and another to send Uyghurs villagers to relatively high-wage factories in south China. The improvement of road and rail connections with Xinjiang’s neighbours heralds an increase in trade along a ‘new Silk Road’, and a reconstructed Kashgar now stands at the centre of a special economic zone touted as ‘the Shenzhen of the west.’

Contending Views

Dissenting views on Xinjiang policy circulate in a variety of forms.

Academics in China: First, there are critiques of official policy that are allowed to be aired widely. These can at times reflect a process of policy deliberation and rethinking inside the Party. Most prominent of these has been the open discussion of aspects of China’s ethnicity 民族 paradigm which is blamed for the country’s inability to secure lasting peace both in Xinjiang and in Tibet. Leading Chinese scholars have criticised the creation of the XUAR for linking ethnicity to specific political institutions, which they refer to as the ‘politicisation’ of ethnicity. They have called for this link to be severed, and ethnicity to be divorced from politics, thereby limiting the state’s obligations towards the Uyghurs as a group. Some go even further and argue that recognition of the Uyghurs as a separate ethnicity was itself an error, that the people in question lacked the requisite ethnic consciousness to be granted this status. The thrust of all of these criticisms is that China erred in borrowing from Soviet policy on the national question in the 1950s, and should draw on its own resources to enhance ethnic minorities’ identification with Chinese 中华 civilization.

Popular Discontent: Alongside these critiques exists a more thoroughgoing dissatisfaction with the current policy, a set of views most commonly encountered in Internet discussion forums and blogs. According to this view, the Uyghurs are ungrateful recipients of generous preferential policies 优惠政策, which place them in a privileged position vis-à-vis the Han. Concern is therefore expressed for the rights of the Han in ethnic minority regions. It is not uncommon to hear Han Chinese complain that they, and not the Uyghurs, are the oppressed minority in Xinjiang. The view that Party officials were failing in their duty to protect the Han boiled over after the 5 July 2009 riots, resulting in angry Han demonstrations which were motivated as much by frustration with Xinjiang’s officialdom as by a desire for revenge against the Uyghurs. ‘We want Wang Zhen 王震, we don’t want Wang Lequan 王乐泉’ was a popular slogan, one that invoked the legendary figure behind the often violent Han opening-up of Xinjiang in the 1950s. Partly in response to this pressure, the Party Secretary Wang Lequan was removed from his post in April 2010.

Dissenting Hans: Prominent Han voices raised in public sympathy to the Uyghur point of view are relatively rare. One exception is the novelist and journalist Wang Lixiong 王力雄, a man briefly imprisoned during his 1999 trip to Xinjiang. In 2007, Wang published a meditation on Xinjiang in the form of a cell conversation with a Uyghur entitled My Western Region, Your Eastern Turkistan 我的西域你的东土. In it he expresses the hope that competing Uyghur and Han historical claims to Xinjiang can be reconciled without upsetting the nation’s territorial unity.[Review by Sebastian Veg]

Uyghur Viewpoints (Inside China): Uyghur voices that seek to contribute to debate within China find few platforms. After speaking out on economic policies implemented in Xinjiang the university professor and Communist Party member Ilham Tohti found himself under increasing pressure to keep silent. Following the 2009 Ürümchi riots, Uyghur Online, a website he had founded, was shut down. His fellow editor Gheyret Niyaz was sentenced to fifteen years in prison on charges of ‘endangering state security’.

Uyghur Viewpoints (Outside China): In its global search for sponsorship and support, the Uyghur exile movement has framed its struggle in a variety of terms. Until it was shut down in 1992, pro-GMD Uyghurs in Taiwan ran what they claimed to be the legitimate administration of Xinjiang 新疆省政府辦事處. Meanwhile, from the 1950s onwards, a rival set of Uyghur leaders based in Turkey carried on a campaign on an anti-Communist, pro-Turkic nationalist basis; these identified with the tradition of the first Eastern Turkistan Republic. While still a large community, Uyghurs in Turkey have now lost the level of political support they once enjoyed. A third wing of the movement in the Soviet Union (and independent Kazakhstan and Kirghizstan) positioned themselves as partisans of a third-world national liberation movement. As China’s relations with its Central Asian neighbours have improved over recent years, these too have lost support.

Today the most active communities of Uyghurs are in Germany (where the World Uyghur Congress is based), the US (home to Radio Free Asia and the Uyghur American Association), Australia and Canada. Debates among exile leaders mirror those among Tibetan exiles, most importantly regarding the question of whether they should seek independence or ‘high-level autonomy’ for their homelands. Led by the one-time entrepreneur Rebiya Kadeer, the present World Uyghur Congress leadership are noncommittal regarding independence. Instead they call for self-determination and the protection of human rights. They support the training of young activists who can lobby effectively in various international forums. These activities are in part funded by grants from the US National Endowment for Democracy.

The mood in the broader exile community is on the whole strongly anti-Chinese; collaboration with Chinese dissidents is not seen as a priority or necessarily relevant. An exception to this is Wuer Kaixi (Örkesh Dölet 吾尔开希), who has played a leading role in the Chinese democracy movement from a base in his adopted Taiwan, while maintaining a strong interest in his native Xinjiang.

Other Ethnicities: Caught in the middle of the Chinese-Uyghur tensions are the other ethnic minorities of Xinjiang, the largest of which are the Kazakhs, Hui, Kirghiz and Mongols. These groups have their own history of conflicts and negotiations with the Chinese state, and they do not necessarily take the Uyghur side on every issue; indeed, in some cases, relations among these groups are strained. Some would argue that China effectively pursues a ‘divide-and-rule’ strategy in Xinjiang; that by dividing up territory and resources between minorities, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has created a sense of competition among local elites. It could also be the case that by pursuing a narrow nationalist claim to Xinjiang, Uyghurs have themselves alienated these other communities. While Uyghur-Han conflict will continue to dominate the headlines, relations among non-Han groups will be an important factor in any reconfiguring of ethnic policy in Xinjiang itself.

International Scholarship

Given its cultural complexities, Xinjiang attracts scholars from fields as diverse as Turkic linguistics and Islamic Studies, as well as those with a background in the humanistic or social scientific study of China. ‘Xinjiang Studies’ is now an international field of scholastic pursuit. Pioneered by European and Russian explorers, the most active centres of Xinjiang Studies are presently in Japan and the USA.

Scholarship on twentieth century Xinjiang has reflected a tension between seeing the dynamics of Xinjiang’s history in its own terms, or as being driven by outside influences. The historian Owen Lattimore (1900-1989) spent decades studying the long-term interactions between China and its ‘barbarian’ neighbours. His work on Xinjiang culminated in the monograph Pivot of Asia: Sinkiang and the Inner Asian frontiers of China and Russia (1950). Lattimore saw Xinjiang as an ‘outer frontier’ of China, standing in relation to the ‘inner frontier’ of Gansu and the Chinese-speaking Hui Muslims. In periods of strength, China had been able to draw on the resources of such inner frontiers to control its outer frontiers. During the Qing, Lattimore felt that this dynamic had given way to a policy of Han colonialism that was not in China’s long-term interests. Lattimore’s idea of the peoples of the north and northwest as a regenerative force in a polity that otherwise tended towards stagnation were echoed by some Chinese scholars in the 1930s. Gu Jiegang 顧頡剛, for example, challenged the scholarly consensus by according China’s Muslims an important role in the anticipated revival of China.

Criticising such views as romantic, others have seen great power rivalries as the key to understanding Xinjiang’s past and present. This line of thinking includes both Sinocentric narratives of long-term Chinese control, such as Zeng Wenwu’s History of China’s Administration of the Western Regions 中国经营西域史, 1936, as well as ‘Great Game’ narratives, which position Russia/Soviet Union and Great Britain as major actors. Allen Whiting and Sheng Shicai offered an implicit critique of Lattimore in Sinkiang: Pawn or Pivot? (1958), which emphasised the extent of Soviet penetration of the region (i.e., Xinjiang as pawn). More recent work has shown a similar dichotomy: Linda Benson’s The Ili Rebellion (1990) recognised the Soviet role in the Second ETR without denigrating the genuine local militants who fought for it as pawns. In contrast, David Wang’s Under the Soviet Shadow: The Yining Incident (1999) described the whole thing as a Soviet plot.

As a historic crossroads, Xinjiang is thought of variously as part of Inner Asia, Central Asia, or Central Eurasia, though such terminology is rejected by scholars in China, who prefer scholarly boundaries to coincide with political boundaries. In China the study of Xinjiang belongs to ‘Frontier Studies’ 边疆学, which emerged as a distinct field in the Republican period, although it is one that drew on traditions of geographic and political thinking that developed during the Qing era.

With a few exceptions, most scholars outside China approach the ongoing conflict in Xinjiang from a position of sympathy with the Uyghurs. The failings of Chinese policy are seen by some as directly to blame for discontent (an ‘internal colonialism’ model); others regard it as being the unintended by-product of the system of autonomy and China’s radical developmentalist priorities. More recently, the focus has turned to issues of language and education policy. Much work on Xinjiang touches on the origins, strength, and prospects of Uyghur national identity. This interest in explaining the reasons for Uyghur discontent in terms other than outside manipulation or religious fanaticism has not been well received in China. With the publication of the edited volume Xinjiang: China’s Muslim Borderland in 2004, a series of bureaucratic twists and turns led to the banning from China of all contributing scholars, who became known as the ‘Xinjiang Thirteen.’ The blacklisting has now been lifted for most contributors to that volume, although for many entry to China remains subject to constraints. The episode has had a negative impact on the free-flowing dialogue and exchange between Chinese and Western scholars [see here]. Research inside Xinjiang remains difficult for outsiders, with archives generally off limits and field researchers closely monitored. Despite this, the possibilities for working in what is still a sparsely populated discipline continue to attract researchers to Xinjiang, and the field is growing.

Historical Background

A small group of European and Russian orientalists took an interest in Xinjiang in the nineteenth century, but the beginnings of the study of Xinjiang properly date to the archaeological and geographical expeditions of the early twentieth century, led by explorers such as Aurel Stein and Sven Hedin. These men were primarily seeking evidence of Silk Road civilizations in Xinjiang’s deserts and Dunhuang’s caves, and found little of interest in contemporary Xinjiang society. Turkologists such as Gunnar Jarring were the first to investigate the cultures and languages of the region’s living Turkic-speaking peoples. Given its disconnect from China during the Republic, few Sinologists took a serious interest in Xinjiang. At the same time, the need to work with Chinese sources deterred Turkologists and Islamic specialists from historical research. It was therefore Japanese scholars who produced the first works on Xinjiang in the Qing and Republican periods, and the tradition of scholarship on Xinjiang in Japan is still strong.

In the West, Harvard’s Joseph Fletcher played an important role in establishing Xinjiang as an object of scholarly enquiry, though he himself regarded it as a ‘backwater’. Fletcher saw the dynamic force in Xinjiang’s recent as past waves of Islamisation emanating from without, from the initial conversion to the arrival of Sufi brotherhoods of Samarkand and Bukhara. Fletcher thus pioneered a distinctly Western interest in the study of Sufism in Xinjiang. By contrast, Soviet scholarship cast the rise of Sufi orders as a Dark Age, and scholars in China largely dismiss them as reactionary agents of theocratic despotism. The study of Sufism in Xinjiang remains a largely European and American occupation, with recent works by Thierry Zarcone and Alexandre Papas. Fletcher’s work also initiated a turn in the study of Qing Empire’s relations with its neighbours, bringing with it the rehabilitation of Manchu as a tool for research on the Qing. At a time when Qing was still thought of as an incarnation of an unchanging China, James Millward’s influential Beyond the Pass (1998) presented the case for seeing the Qing as an early modern empire, and its actions in Xinjiang as a form of colonialism. Kim Ho-dong’s Holy War in China (2004) and Laura Newby’s The Empire and the Khanate (2005) belong to this tradition.

Media Representation

Xinjiang is no longer the remote and obscure place that it was during the early years of the PRC; major publications such as The New York Times, Christian Science Monitor, and Wall Street Journal regularly run stories on events there. Despite this, direct reporting from Xinjiang remains highly restricted, and most newsworthy events take place far from the eyes of foreign journalists.

The 2009 Riots and Beyond: After the 2009 riots in Ürümchi, Beijing was confident enough of its own position to invite reporters to tour the scene of the violence. For the first time, tweets told of spontaneous protests breaking out on Ürümchi’s streets, and photographers recorded scenes of Uyghurs braving the riot police to present their case to the world. At the same time, the flow of news in and out of Xinjiang was curtailed by the cutting of Internet and telephone communications. Journalists were strongly discouraged from travelling south to Kashgar, and some were detained. Whether or not China will adopt a similar policy towards future outbreaks of violence, or revert to outright bans on reporting (as has been the case in Tibet), remains to be seen.

In the meantime, a steady stream of accounts of a low-intensity conflict is reported internationally on the basis of Chinese accounts, which often make assertions about terrorist activities that cannot be independently verified. Certain Chinese claims about groups such as the Turkistan Islamic Party (TIP) are accepted at face value, others are treated with greater scepticism. For the most part, countries that have their own stake in the ‘terrorist threat’ story, such as India or Russia, tend to be more credulous. In response to such Chinese reports, often the only available alternative views are press releases from Uyghur organizations such as the World Uyghur Congress, or information sourced by Radio Free Asia (RFA), which has a Uyghur-language service. RFA Uyghur in particular is a focal point for the dispersed Uyghur communities living around the globe, and it regularly broadcasts interviews and news from within Xinjiang, all with a strongly anti-Chinese bias. RFA is funded by American congressional grants, and not surprisingly China regards it as a propaganda tool of the US imperium. China tries, with limited success, to jam its broadcasts into Xinjiang.

Resorting to partisan Uyghurs for commentary fuels perceptions in China that Western, as well as non-mainland Chinese and Japanese, media condones, or even tacitly encourages, anti-Chinese violence by Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Within China, Rebiya Kadeer and her colleagues are demonized to no lesser degree than Osama bin Laden was in the West. To understand Chinese attitudes, therefore, we might perhaps imagine a situation in which acts of violence in New York or London were followed by sympathetic interviews with al-Qaeda leaders on Chinese TV. In 2009, ‘angry youth’ websites such as Anti-CNN caught out the Western press in at least one embarrassing error, when Rebiya Kadeer was allowed to present a photo from a riot elsewhere in China as a scene of confrontation in Ürümchi [China Daily]. (Uyghurs countered that the photo was deliberately circulated by Chinese to induce this mix-up). News sites such as the Global Times which are overtly sympathetic to the official position now act as the mouthpiece for Chinese complaints against the Western press. A Global Times spin-off site called True Xinjiang serves a repository for much reporting on Xinjiang.

Western indulgence of Rebiya Kadeer was confirmed for many in China by the release of the documentary Ten Conditions of Love, a biopic told largely in Rebiya Kadeer’s own words. The film depicts in a highly romanticized fashion Kadeer’s struggle against the Chinese. Produced by Australia filmmakers, the documentary first screened at the Melbourne International Film Festival in August 2009. This provoked a storm of protest and led to a clumsy intervention by Chinese diplomats who sought the withdrawal of the film from the festival and who requested that the Australian government deny the ‘terrorist’ Kadeer a visa to enter the country. Such action only raised the profile of the film, and of Rebiya herself, and it led to subsequent screenings in festivals around the world – accompanied by similar PRC expressions of dismay and official expression of ‘hurt feelings’. Since this episode, China seems to have thought better of attacking Rebiya so publicly, but the documentary remains a source of controversy. Recently questions were raised in the Australian press as to why the national broadcaster (ABC), who had acquired the rights to the documentary, nevertheless had decided not to screen it on its international station, the Australia Network. Responding to this pressure, the ABC later announced that it intends to show the film.