One of the many abiding legacies of Confucius is his legendary work as an editor. The Mentor-Exemplar of Ten Thousand Ages 萬世師表 is famed for editing the classic Book of Songs 詩經, thereby creating China’s earliest work of literature while at the same time establishing a tradition of censorship: according to legend he edited some 3000 folk songs and poems down to a scant 305 for the edification of his disciples. Despite the divergent origins and context of the poems (many sexual or political), after he had finished with them Confucius praised his hand-picked collection for ‘having no depraved [or, rather, heterodox] thoughts’ 思無邪. He supposedly also applied his talents to historical records and, as we have noted elsewhere, the Master is the acknowledged creator of the ‘Spring and Autumn Style’ 春秋筆法 of didactic prose which influences Chinese writing and speaking to this day (see Totalitarian Nostalgia and New China Newspeak).

The survival, reworking and frequent destruction of local forms of culture, writing, lifestyles, ideas and practices is at the heart of China’s millennia-0ld civilisation. It is a story partly reflected in Songs of the South 楚辭. As David Hawkes says of the shamanism that produced that body of poetry:

The impression given by Confucian historians that the shamanism of Chu was an outlandish regional aberration is misleading. Shamanism was the Old Religion of China, dethroned when Confucianism became a state orthodoxy and driven into the countryside, where it fared much as paganism did in Christian Europe: sometimes tolerated and absorbed, sometimes ferociously suppressed.[1]

Successive power-holders, be they regional or dynastic, encouraged by ideas about unity and homogenisation since the Han dynasty, have probably destroyed or distorted far more than they have preserved. In China Heritage we acknowledge and introduce aspects of China’s various vital traditions, and we celebrate the genius of those not hidebound by orthodoxy and conformity.

***

From its earliest days in power in the 1950s, the Chinese Communist Party has sought to preserve acceptable elements of the tradition while sequestering, studying and censoring those things that it finds unpalatable.

In the late 1970s, I became friendly with Fan Yong 范用, the head of Joint Publishing 三聯書店 and one of the founders of the the magazine Reading 讀書 in 1979. Over the years, among other things, he told me about his role in helping collect material at second-hand bookstores throughout the country both for safekeeping and to ensure dangerous material no longer circulated within the general population. Similarly, another literary friend, the bibliophile Huang Shang 黃裳, was one of a team that collected material related to traditional theatre forms as part of the government’s aim to purge the stage of unhealthy and ideological unsound works. (The process of ‘civilising’ Chinese theatre which, during the era of High Maoism reached something of an apogee with the Revolutionary Model Operas 革命樣板戲, began in the late-Qing dynasty and continued, in fits and starts, throughout the Republican era, 1912-1949.)

In recent years, the Chinese party-state has issued a number of major pronouncements on how to best gazette, order and direct China’s heritage and traditional cultural forms. The world of the theatre has enjoyed both largesse and further decimation on the basis of what is called The Classics Project 精品工程, which ranks and rewards forms of stagecraft that are deemed to reflect appropriately the Party’s Core Socialist Values 社會主義核心價值觀. Directed culture is hardly unique to China and, in recent decades, the ideology of the Creative Industries industry has seen the marriage between state values and commercial imperatives holding sway in other climes.

***

In the People’s Republic of China film making is often referred to as ‘an art of regret’ 一門遺憾的藝術. The expression is attributed to the film-maker Xie Jin 謝晉, a Shanghai cinéaste with a celebrated career as a talented party propagandist; as such the expression ‘art of regret’ may well sum up Xie’s own frustrations, not only with the limitations of film, but with the political imperatives that dogged him, and which he served.

Andrea Cavazzuti’s work offers us other regrets: regret about a time, only ten years ago, when party-commercialisation had not entirely suffocated local creativity; regret over a revived and now fading art form; regret regarding the nature of documentary film itself; and, the ever-present regret resulting from the frustrations attendant upon those who seek independent funding to pursue their work. His then is a story of regret, the first part of which we present here.

***

Andrea Cavazzuti was born in Milan in 1959, although raised in Carpi (a town near Modena and Bologna). Originally interested in computer science, he graduated in Chinese language and literature from Ca’ Foscari University in Venice. After two years at Fudan University in Shanghai (during which time he pursued an interest in black and white photography), and military service in the Italian Alps, he worked as an area manager for a major company in Hong Kong. In 1990, Cavazzuti opened a representative office for the same company in Beijing but, in 1999, at the height of his business career, he resigned to pursue artistic endeavours. He had continued to make photographs and, in 1994, he started working with video. His first significant film was a trilogy about contemporary Beijing with the artist Olivo Barbieri, followed by Fiction Kids and another trilogy — The Fastest Museum in the World — with Carlo Laurenti. Since then he has collaborated with Chinese and international artists on numerous film and video projects. He lives in Beijing.

‘Stories of Regret, Part I — the Zhang family of Huayin’ was edited by Andrea Cavazzuti for China Heritage from his film ‘Fest Bianche, Caos e Marionette (Breve viaggio musicale tra Shanxi e Shaanxi)’.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

30 April 2017

Stories of Regret, Part I

The Zhang Family of Huayin

華陰張家老腔樂隊

Andrea Cavazzuti

In 2007, I embarked on an ambitious project with Wu Man 吳蠻, a celebrated Chinese musician based in the United States. Wu is expert in the art of the pi’-p’a 琵琶. Our hope was to film and record living examples of local traditional Chinese music. By ‘traditional’ we meant musical forms that had been performed and transmitted over the centuries. The ‘living’ were those musical works and performers that were still vitally part of modern China, as well as being lively.

Aided in our project by various musicologists such as Stephen Jones, and others from the China Arts Research Institute 中国艺术研究所 and the Shanghai Conservatory 上海音乐学院, we identified some musical groups that were still active in Shanxi and Shaanxi, provinces in northwest China.

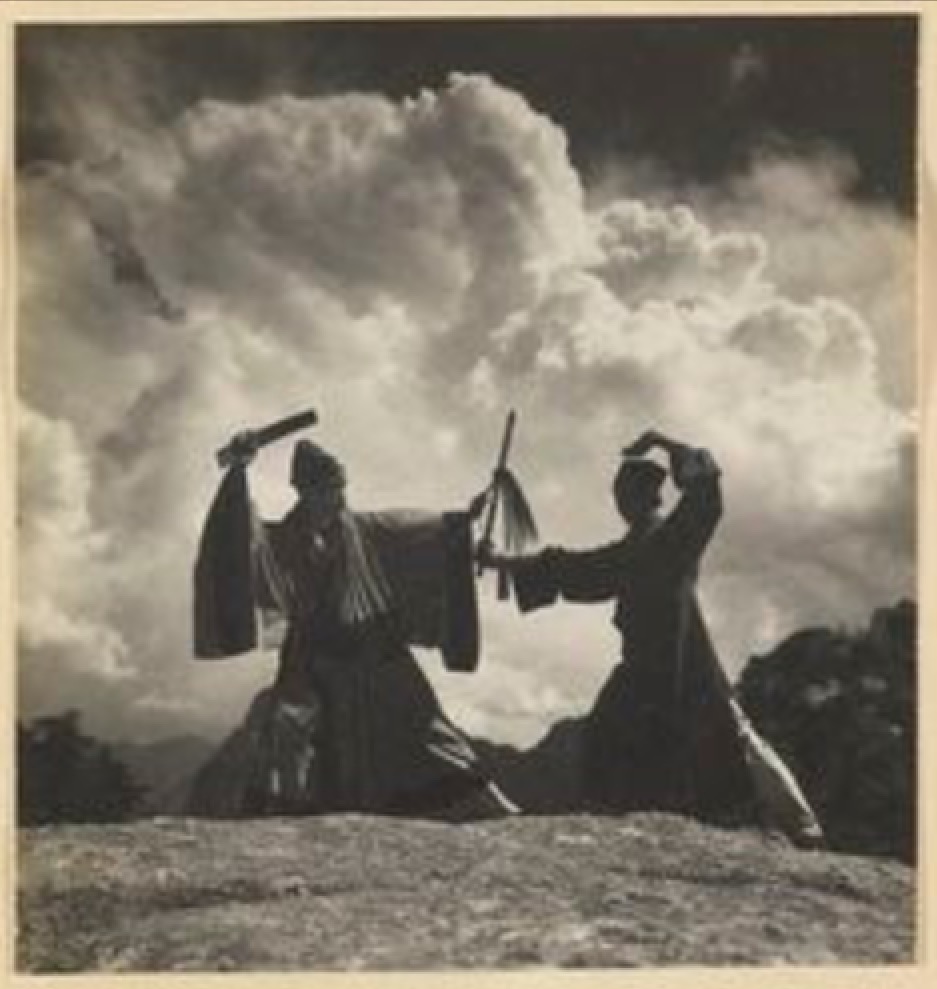

In 2008, Wu Man and I travelled to Huayin 華陰 county at the foot of Hua Mountain 華山 in north-eastern Shaanxi Province. One of China’s Five Sacred Peaks 五嶽, Mount Hua was celebrated in 1935 by the then-Beijing-based photographer Hedda Morrison in a book about the peak and the Taoist practitioners who lived there.

In the village of Quandian 泉店村 we found the Zhang family known for its laoqiang 老腔 performances.[2] The group, part of a tradition of shadow puppet performance that traced its origins back to the early Ming dynasty in the fourteenth century, made a brief appearance in To Live 活著, a film released in 1994 by the famous north-eastern director Zhang Yimou 張藝謀. They also featured in the stage version of White Deer Plain 白鹿原 by the Beijing theatre director Lin Zhaohua 林兆華. Lin encouraged them to ‘come out’ from behind the screen of shadow puppet theatre to perform their music and songs in the open. In Lin’s play they were but one group among a number of other Laoqiang and Qinqiang 秦腔 performers; they added a touch of local colour to a production set in the dying days of the Qing dynasty and the early years of the Republic of China, a century ago.

For the thirteen-minute film of the

Zhang Family of Huayin,

click HERE

In the Cultural Revolution, the laoqiang performers of Quandian Village had been obliged to adapt their art to performing Revolutionary Model Operas [locally called 樣板劇兒], as they say in the film. They didn’t like it but at least it kept them active during those fallow years.

White Deer Plain was something of a turning point which gave them some artistic exposure in the capital and helped them survive as a band in China’s new consumerist ‘société du spectacle’. We met them just before this latest twist in their story. Although Huayin, with its flourishing tourist industry and a major highway nearby, the musicians still lived quite, simple lives. Their days were spent in the fields and in their spare time they made puppets and played music together. For the sake of transmitting this cultural heritage, they were also trying to write down their music scores.

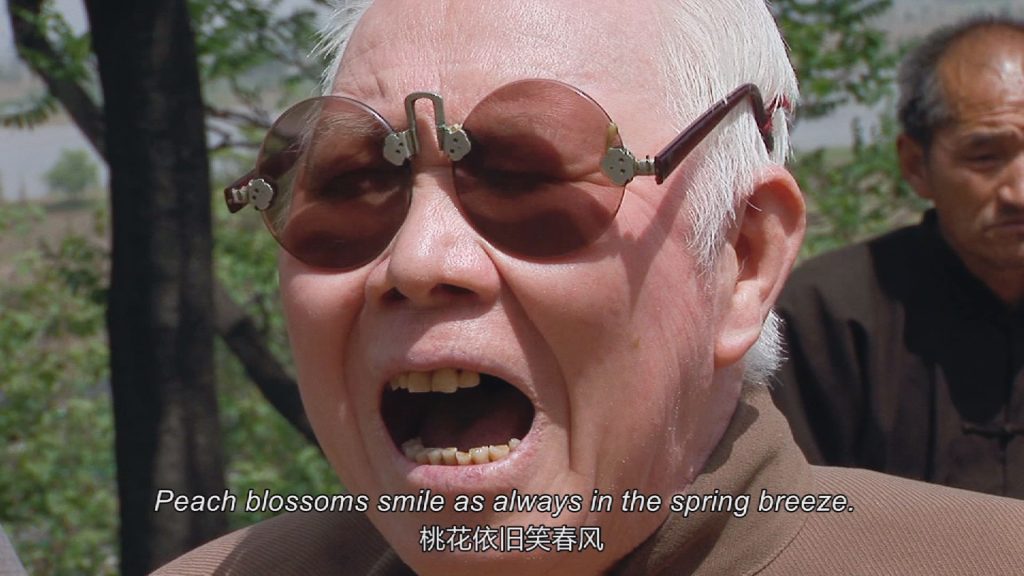

They played a few times for us and performed a short puppet play. Locally, they didn’t have many chances to perform in public: today people were busy with other things and different interests, so the band couldn’t survive on their music alone. In 2006, the Ministry of Culture in Beijing included them in the national list of Intangible Culture Heritage 非物質文化遺產, and they were rewarded with state funding. The money took years to reach them and by the time it made it to Quandian the layers of sticky-fingered bureaucracy had reduced the amount to a pittance. They had just enough to start a small training class, although the youngest applicant was a sixty year-old. The head of troupe that we interviewed was Zhang Ximin 張喜民. He is a charismatic figure and everybody in the group performed for us with energy and evident excitement.

Since Wu Man and I made this film, nearly a decade ago now, the group has been co-opted by the propaganda-showbiz-industrial complex of mainland China. One day what must be about eight years ago I went to see them backstage in a studio at China Central TV (CCTV). They had been corralled there and kept waiting for hours with no food or water. Eventually, they were herded around by a young production assistant who yelled at them for not moving fast enough. Then you would see them on national TV, cameras zooming back and forth or panning overhead as if in a drunken frenzy. The bedraggled performers looked tired and sweaty, their faces devoid of any emotion. The media celebrated the appearance as a sign of respect for a cultural tradition.

I happily remember Zhang Ximin’s proud and ecstatic smile when he was instructing his young nephew or giving Wu Man a lesson in his ancient art.

Note

[1] David Hawkes, translated and introduced, The Songs of the South, An Ancient Chinese Anthology of Poems by Qu Yuan and Other Poets, Penguin, 1985, p.19.

[2] An online encyclopaedia entry on laoqiang describes this musical form in the following terms:

其聲腔具有剛直高亢、磅礡豪邁的氣魄,聽起來頗有關西大漢詠唱大江東去之慨;落音又引進渭水船工號子曲調,採用一人唱眾人幫合的拖腔(民間俗稱為拉波);伴奏音樂不用嗩吶,獨設檀板的拍板節奏,均構成了該劇種的獨有之長,使其富有突出的歷史和文化價值,世代流傳,久演不衰。但又鑒於該劇種這一特殊情形(家族戲),目前依然處於行將消亡的瀕危狀態,迫切需要長期保護。