Wairarapa Readings

Wairarapa Readings 清漪劄記 celebrate the variety and vibrancy of China’s literary heritage. They introduce literary texts and translations aimed at students of traditional Chinese letters who are interested in the world that lies beyond the narrow confines and demands of contemporary institutional pedagogy. They also reflect the long-term interest of The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology in ‘cultivation’ 修養.

***

In Living with Xi Dada’s China — Making Choices and Cutting Deals, I noted that:

Scholar-bureaucrats in dynastic China often found themselves working for a corrupt court or during a time of strife and contention. Rather than abandon hard-won official careers — after all they had spent long years studying and taking exams so they could become officials — they chose to submit to court rule, to tolerate the tedium of routine and to survive. Many resiled from active engagement with the politics of the day or declined to take a stand over any particular issue. Rather than retire from the world entirely 隐退, however, they took an even more passive route to survival: they became recluses at court 朝隱, hiding in full sight. This hallowed term may be relevant again in China; it may even resonate with many of you.

People from all walks of life, both in and outside China, attempt to pursue a suitable modus vivendi in what promises to be the extended era of party-state-army leader Xi Jinping. Under China’s previous Great Helmsman, Mao Zedong, some, like Zhao Hang, who is interviewed below, worked out how to survive just ‘out of range’.

The following oral history interview by Sang Ye is part of The Rings of Beijing: China’s Global Aura. This translation first appeared in China Heritage Quarterly, the precursor of China Heritage, under the title 1949-2009: Sixty Years Out of Range. It is reprinted here with minor changes and the addition of Chinese original as part of a series including:

- Contentious Friendship, China Heritage, 29 April 2018; and,

- The Possible and the Probable, China Heritage, 22 May 2018

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

25 May 2018

Out of Range

彀外遺少

An Oral History Interview by

Sang Ye 桑曄

Translated and Annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

Zhao Hang 赵珩 is a gourmand and connoisseur of traditional Chinese opera.

My humble surname is Zhao, personal name Lüjian. My literary name is Hang, as in ‘Where is the white jade ornament from the State of Chu’.[1] But there I go, off on a digression before we’ve even started. You probably think it’s odd that I have a literary name, what an antique! There’s no space marked ‘literary name’ on one’s ID card. It does indicate when you were born. I was born in December 1948. I’ve lived through one whole rotation of the jiazi 甲子, the sixty-year traditional calendar; I’ve experienced the full cycle. Sixty years is the lion’s share of a person’s life, once you’ve reached sixty you begin ‘counting off the years like rosary beads’.[2] 敝姓趙,名履堅,草字珩,以字行,楚之白珩猶在乎的珩。得,開篇就岔了吧,您說您這人兒怎麼還有字呢,這也忒古董了吧,身份證上沒這行啊。身份證上倒是有出生年月那一行,那一行我是1948年12月,六十甲子打轉身,已經活了一個大輪,經驗一個週期了。

Contemplating the transient world, it seems that sixty years is but an instant. But the ‘instant’ of history covering the last fifty odd years, has been a rather special one. In this particular instant, Chinese society changed dramatically, culture was turned on its head and people’s lifestyles have been completely transformed. 對於一個人,六十年是大半生,手挼六十花甲子,循環落落如弄珠,已經到回首前塵年歲了,對於歷史卻只不過是一瞬。可是最近半個多世紀的這一瞬還是有些特別的,是中國社會經歷了巨變,文化發生了顛覆,生活方式也隨之有了大變化的一瞬。

I’m too lazy to keep pace with the changes. A few years back, I was invited to write something about how ‘a classical sensibility might cope with modern society’. I found the topic too scary, too broad. It was hard to put my thoughts into words, to express them with any clarity. So I told them that ‘sensibility’ is an intensely personal thing. Society is always changing. A ‘classical sensibility’ boils down to identification with one’s culture. It wasn’t something I was equipped to write about; I couldn’t do it. 我是懶人,又是不大跟得上步伐的那種,所以前些年有人給我出了個如何以古典情懷面對現代社會的題目約稿子,這個題目太大,也太厲害了,很難說,很難說清楚。所以我就告訴他情懷是個人的,社會是發展的,什麼叫古典情懷啊,不過就是文化認同罷了,由我來回答這題目不合適,寫不了。

I’ve never thought of myself as the heroic sort of individual who goes against the tide and weathers all adversity. All I ever wanted was to be a mild-mannered and decent person with a rich appreciation of the art of living.[3] 我從來沒有想過要頂風傲雪做了不起的人物,我只想做平淡良善懂生活的人,活好這輩子。

This world of ours is made up of very different sorts. You can take the approach of [the Han-dynasty historian] Sima Qian and strive to ‘a thorough comprehension of the workings of affairs divine and human, and a knowledge of the historical process’.[4] Or you can bury yourself in detail like [the Northern Song writer] Meng Yuanlao who, in Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendours Past, describes in meticulous and encyclopaedic detail the capital city of Kaifeng from the Chongning to the Xuanhe years [of the Song emperor Huizong, 1102-25 CE] — its streets and marketplaces, local customs and festivals, foods and entertainments, lifestyle, livelihoods and musical and theatrical divertissements.[5] 所以呢,司馬遷究天人之際, 通古今之變是一種,孟元老寫《東京夢華錄》,把崇寧到宣和的開封街巷坊市、民風時令、飲食起居、歌舞百戲無所不包地記錄下來也是一種,不同是明擺著的,但都成就了一家學說。

But then there are people who touch the very core of your being like Xi Kang [third century, one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove]. When Xi Kang, this ‘serene and sedate’ man, was sentenced to death by the ruler Sima Zhao he requested a lute. After he had finished playing Xi Kang declared that ‘the Melody of Guangling was no more’.[6] No matter how many Xi Kangs Sima Zhao killed he could never entirely sever the threads of culture; its not that easy to destroy intangible heritage. Of course, it’s best if it passes from generation to generation like a torch. But so long as there is sufficient fuel the fire will not be extinguished. The fuel can be heaped in piles somewhere; the moment it is licked by flame, it will reignite. Cultural heritage can neither be burnt to ashes nor buried alive.[7] 那震撼人心的廣陵散於今絕矣所凸現的是嵇康凜然從容,其實司馬昭再多殺幾個嵇康也是殺不斷文化傳承的,誰想斷絕一樣好東西都沒那麼簡單。文化傳承,能直捷地薪火相傳很好,不能的話還有另外一種狀態叫積薪未燼,柴火都划拉到一塊兒了,所有細節都在,好大好大的一堆,而且也不僅是一堆啊,這是焚也焚不盡,坑也坑不完的。

In the early 1960s, my family moved to Cuiwei Street to the west of the city [near the Military Museum]. Before that we lived at Huan Yuan 幻園, the Garden of Illusion, 61 Dongzongbu Hutong. Many luminaries had visited my family there: [the opera singer] Mei Lanfang, [the artist] Chen Banding and [the politician and soldier] Zhang Xueliang. [The singer] Zhang Junqiu even lived there for a while. You could say that our garden residence played a minor role in the history of old Beijing. Time passes and the seas turn into mulberry fields. Battered by bitter autumn winds, that courtyard house decayed and collapsed. It’s like the famous gardens of the Tang dynasty capital of Chang’an described in Mr Feng’s Record of Sight and Sounds,[8] just a modern footnote to the old story about how a place can go from splendour to desolation in just a few generations. 1960年代初,我家搬到了西郊的翠微路,此前在東總布衚衕61號,幻園。幻園裡接待過梅蘭芳、陳半丁、張學良,張君秋亦曾寄寓,可以說是北京近現代歷史的一個小角。世事滄桑,那院子後來就在秋風蕭瑟中日漸頹敗,好比是《封氏聞見記》里唐代長安名園更迭變易迅速,數代化為丘墟的一個現代注腳。

My great grandfather, Zhao Erfeng, was the governor-general of Sichuan in the late-Qing era and the dynastic representative for Lhasa.[9] My great-uncle Zhao Erxun was the head of the Qing Dynastic History Office during the Republic, in charge of compiling the Draft History of the Qing Dynasty.[10] Following the establishment of New China in 1949, my father, Zhao Shouyan, was made deputy editor-in-chief of Zhonghua Books. He was put in charge of punctuating and collating the Twenty-four Dynastic Histories.[11] 我的曾祖父趙爾豐是清末的署理四川總督兼駐藏大臣,曾伯祖趙爾巽是民國時候的清史館館長,領修《清史稿》,父親趙守儼是新中國的中華書局副總編,主持過二十四史的點校。

There’s a long history of home education among ‘those raised on the fragrance of books’. I was home schooled. Traditionally, the purpose of study was self-cultivation as well as having the means to support your family, help govern the state and bring peace to the world [as it is put in the Confucian classic The Great Learning].[12] Given the times, the most I could hope for was self-cultivation. So at home I read the Book of Songs, The Songs of the South, Tang poetry, as well as Record of Discarded Dust, Eastern Capital: A Dream of Splendours Past, A Record of Dreams and The Notebooks of Yueman Studio. I particularly enjoyed reading scholar-notebooks because they had a strong narrative, and they led you off in all directions.[13] Naturally, I also learned the essential texts by heart, beginning with Confucius’ Analects and Mencius and going on to major works in the collection The Ultimate in Classical Prose.[14] I used to be able to recite the whole of Mencius, but it’s been years since I’ve done so, so I’ve forgotten a lot of it. Though, I can still recite the Analects from any line you care to mention. 所謂書香子弟、家學淵源吧,那個時候我就在家讀書。讀書要修身、齊家、治國、平天下,那時候的社會至少還能做到修身吧,我就在家讀《詩經》、《楚辭》、唐詩,還有《揮麈錄》、《東京夢華錄》、《夢梁錄》、《越縵堂讀書記》。我愛讀筆記這一塊,有故事性,而且能旁及其餘。當然還得背誦那些看家的,先是《論語》和《孟子》,然後又背了《古文觀止》各篇。《孟子》原來能通背,現在總不用就不行了,《論語》沒問題,現在也還能隨意抽句起頭背《論語》。

Because he was so absorbed in his work on the Twenty-four Dynastic Histories, my father didn’t really mind what I read, as long as I concentrated on classics like the Analects and Mencius. He was happy to let me follow my own interests. I enjoyed a liberal and harmonious home environment. These days many parents burden their children with their unrealised aspirations. They force them to work hard, but it shows disrespect to children. For me reading is pure enjoyment, a way of amusing myself.[15] I also like painting and ice-skating. I even made a bit of a name for myself as a skater: I was a ‘Grade Three’ athlete. I enjoy stamp collecting too, and I have something of a reputation as a philatelist. I’m on the board of the National Association of Chinese Philatelists. Looking back, when I collected stamps in my youth it was for the sheer joy of it. It’s completely different these days, and not just for stamp collectors. There’s a whole bubble market out there for all sorts of collectibles. A quiet hobby pursued for the joy of it is now akin to playing the stock or real estate markets. Everyone invests money in it and everyone talks about it, but all they’re only interested in a collection’s value — historical, artistic and scientific. It’s just a game pursued for financial gain. 那時候我父親也不大管,他忙二十四史,除了看家的《論語》和《孟子》,放任我隨興趣看自己喜歡的書,享有寬松和諧環境。現在很多父母把自己沒實現的理想寄託在小孩子身上,刻意培養,實在不尊重小孩子。在我來說讀書也是享受,也屬於玩兒,除了讀書還畫畫,還滑冰,滑冰還滑出點兒名堂,是三級運動員;還集郵,集郵也集出點兒名堂,現在還是中華全國集郵聯合會的理事呢。回想起少年時的集郵,那是一種純粹的愉悅,當下已經大變了,不僅集郵,整個收藏市場都浮躁,安安靜靜的小眾文雅事變成了和股票、基金、房地產似的大眾投資,誰都在談論,可是誰都關心藏品的歷史價值、藝術價值、科學研究價值,成了財富遊戲。

My mother graduated from the Catholic Fu-jen University,[16] but she’s never had a formal job in the new society. Instead, she stayed home and translated books like [Yung Wing’s] My Life in China and America[17] and [Mary Wollstonecraft’s] A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects. That’s why I’ve read so much fiction in translation. During the Cultural Revolution people gave me books they’d stolen from the public libraries, but one look and I realised I’d already read them: Balzac, Hugo, Goldsworthy, Gogol, Turgenev, Dickens … I’d already read nearly every novel that had been translated up to that time. 我母親是天主教的輔仁大學畢業,在新社會她也沒有正式參加工作,在家裡翻書,翻譯了《西學東漸記》和《女權辯護》。因為這個原因,我也看了不少的翻譯小說,文化大革命中有人把公家圖書館的書偷出來讓我看,我一看都是已經看過的,巴爾扎克、雨果、高爾斯華綏、果戈里、屠格涅夫、狄更斯,我發現我已經把文革前翻譯的小說基本上全都看過了。

From the start of the Cultural Revolution I stayed at home reading. I also copied Western oil paintings. Because my family was regarded as a ‘dead tiger’ [with no authority or profile], we weren’t targeted too viciously. We lost some books, that was about it. Back then, apart from big-character posters people wrote down almost nothing. As the old saying has it, trouble flows from the mouth, but to make a crime stick there had to be something in writing too. To avoid trouble people burned or pulped all calligraphy and letters. The wastepaper baskets in every house were completely empty. 文化大革命開始後,還是在家讀書,另外還臨摹西洋油畫。因為我家是死老虎,也沒受到太大的衝擊,簡單說就是損失了一些書。那時候除了大字報,社會上連字紙都少見了,禍從口出,可是能把罪名坐實了的還得是文字,所以但凡是手書墨跡、往來信函,都以火攻水淹的辦法處理掉,免得招麻煩,家家的字紙簍兒都空空如也。

I never considered reading or study a worthless pursuit. I had no idea when society might turn the corner, but I believed that eventually things would return to normal. They had to. I knew in my heart that they wouldn’t always treat traditional culture with such contempt. During those years I concentrated on reading history and scholar-notebooks like A Record of Nurturing the New from the Studio of Tireless Pursuit, Disputations on the Seventeen Histories, Notes on the Twenty-two Histories and Researches into Anomalies in the Twenty-two Histories.[18] I also read translations. I loved the details of nineteenth-century English rural life in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. I would read a section and then throw open the window and take in the air. It might be noisy and bustling outside or dead still — it was as if I was in another world. And so I was. 我當時認為讀書絕對不會沒用的,我不知道這社會會在什麼時候拐彎兒,但是相信它一定會回到正常,也必須回到正常。傳統文化不會永遠被人踐踏在腳底下,這一點在我頭腦中很清楚。這段時間我讀的主要是些關於史書的讀書筆記,比方《十駕齋養新錄》、《十七史商榷》、《廿二史剳記》、《廿二史考異》、《陔余叢考》。同時也讀翻譯,我非常喜歡《弗洛斯河上的磨坊》,裡面都是些十九世紀英國鄉下的家長里短。讀完一段兒,推開窗子透透氣,外面或者在喧囂,或者是沈寂,恍若隔世,也確實是隔世。

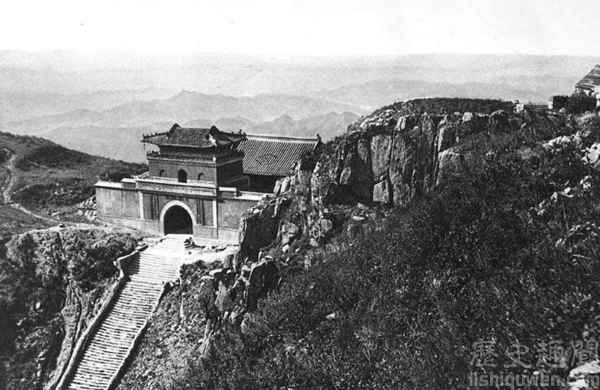

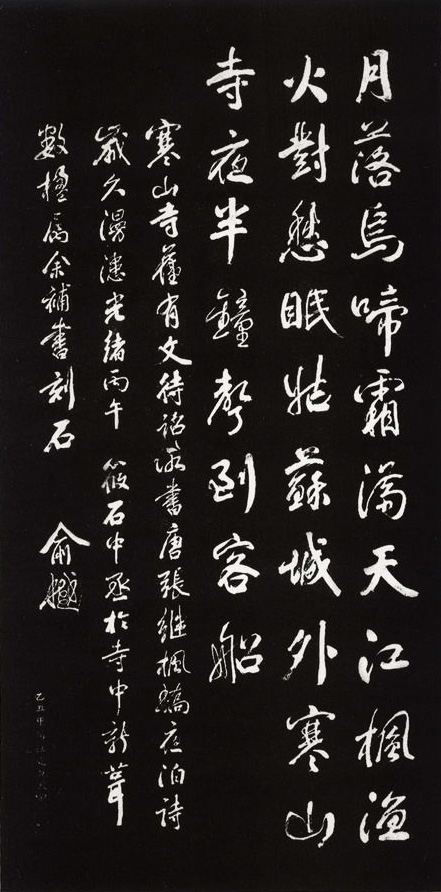

The only thing I did out of character was to get hold of a Red Guard travel permit during the Great Link-ups of the second half of 1966.[19] I used it to go sightseeing around China. I simply wanted to live that dream of the ancients; having ‘read 10,000 books’ I wanted to ‘travel 10,000 li’.[20] I never read any big-character posters — best not to pollute your eyes with that sort of language. I stayed in the hotel on the peak of Mount Tai [in Shandong] for three days. It rained for two days non-stop. When I woke on the afternoon of the third day, the sun was shining through the window and the whole mountain was bathed in shimmering green light. I felt the truth of [the Tang-dynasty poet] Du Fu’s line about ‘at a single glance … all the other mountains grow tiny beneath me’[21] and I realised that when [the Tang-dynasty artist] Li Sixun created ‘gold-and-green landscapes’ he was not exaggerating at all.[22] After that I went to Suzhou eager to take a boat up the Grand Canal to Hangzhou so that I could experience for myself that famous poetic line [by Zhang Ji of the mid-eighth century] ‘And I hear, from beyond Suzhou, from the temple on Cold Mountain,/ Ringing for me, here in my boat, the midnight bell’.[23] But I ended up going in the opposite direction — from Hangzhou to Suzhou. 文革中的出軌行動是1966年下半年我也弄了一張紅衛兵串聯證,一個人出去遊山玩水了。我純粹是想在讀萬卷書之後行萬里路,所以從來不看任何大字報,那種文字還是不入眼的好。我到泰山頂上的賓館住了三天,兩天陰雨,第三天下午一覺醒來,隔窗看到了太陽,此刻的泰山一片蔥綠,蔥綠籠罩在金光之中,體驗到了杜甫的一覽眾山小,也從此相信李思訓的金碧山水絕對沒有誇張。然後又到了蘇州,又特意坐船走大運河從蘇州到杭州,體驗姑蘇城外寒山寺,夜半鐘聲到客船的意境,但行走路徑相反。

***

In 1969, educated young people from the cities were packed off to the countryside to be re-educated by the poor and lower middle peasants. They sent me to Inner Mongolia. You had no choice. If you refused they just kept coming around to ‘mobilise’ you. But I snuck back to Beijing after a year and lived ‘a life of leisure’ at home. I didn’t worry about not having a residency permit. I spent my time punctuating the History of the Han dynasty. I had the cheapest Zhujian Studio edition and I punctuated and annotated it from cover to cover. Then I started working on the Records of the Historian [by Sima Qian], but didn’t manage to finish it. In the three years I remained unemployed at home, I also copied out Confucius’ Analects in formal small-script calligraphy on a long scroll, which I eventually had mounted. I still have it. I also reread all of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales and stories with my wife — ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, ‘The Flea and the Professor’, ‘The Silver Shilling’. I even wrote an appreciation of the stories as we read them. Anderson’s fairy tales aren’t just for children, after all. On Chinese New Years Eve in 1973 my family all got together, ‘trimmed the wicks of our lamp, ground some ink and made a painting together’.[24] I painted [the vanquisher of ghosts and demons] Zhong Kui, my mother added the background scenery and my dad composed a poem and wrote it in calligraphy on the painting.[25] It was to repel evil spirits big and small. We really were out of step with the times. 1969年,知識青年上山下鄉接受貧下中農再教育,就把我送到了內蒙古,不去不行,你不去就不停地動員你。一年之後我就回來了,我就自動回來了,在家賦閒,沒戶口就沒戶口吧,我在家點《漢書》。用的是最便宜的竹簡齋本,我在上面標點正文寫注釋,《漢書》點完了點《史記》,《史記》沒點完。除了點書,賦閒這三年的功課還是小楷錄《論語》,還把小楷裱成了長卷,現在還留著。此外我還和內人一起重讀了安徒生童話,皇帝的新衣,跳蚤和教授,一枚銀毫子,還寫了些讀後感,安徒生童話不僅是小孩子的最愛。1973年除夕,我家還挑燈研墨聯袂繪丹青呢,我畫了個鍾馗,母親補景,父親題詩,大鬼小鬼進不來,的確是很不合潮流。

In 1974, they reinstated my Beijing residency permit. I was allocated work in the Chinese Medicine Hospital. Everything takes you to traditional medicine, be it Buddhism, Taoism, Shamanism or even Confucianism. But I wasn’t interested in medicine so when the Open Door and Reform policies were launched [in 1978] I took the exams to get a job with a publishing house. Before retiring I was the Editor-in-Chief of Yanshan Publishers, a publishing house specialising in books on Beijing culture and history. During my years there I edited a number of books and even wrote two myself. I started out writing about food because I’m lazy and a bit of a glutton. The word ‘taste’ in English and ‘wei 味’ in Chinese have similarly complex layers of meaning. Both are very hard to pin down. You could buy my books, but I’m not sure I make sense of it… … 1974年戶口回來了,把我分配到中醫醫院,由佛入醫、由道入醫、由巫入醫,由儒入醫,這好像是專業比較相通的工作啊。可是我對醫學沒興趣,改革開放以後就考去了出版社,退休之前的位置是專出北京文史的燕山出版社的總編輯。進出版社以後的這些年,編了一批書,寫了兩本書。我先是寫了本吃的書,我是懶人,又是饞人,可是中文的味和英文的taste有異曲同工之妙,其實很難用文字詮釋,只買我的書來看,恐怕是根本不行的 ……

Though I’ve read [the Taoist] Laozi and Zhuangzi, I haven’t delved much into philosophy, and I have no particular insights to speak of. Neither have I studied broader historical problems; I’m not good at big topics. I do have my own view on various issues of course. Take the Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu of Dunhuang, for example. What was so despicable about him? I don’t think he gave away those precious scrolls to Aurel Stein for practically nothing out of sheer ignorance. After all, once he got the money he devoted himself to covering up those elegant, beautifully painted and fluent wall paintings and statues which had suffered badly from erosion over the years. In their stead, he created a pile of crude, artless and vulgar rubbish. Then there is the [anti-Manchu activist] Gu Tinglin. In his later years, he didn’t just choose his friends in accordance with his strict political principals but became close to people on the basis of shared cultural views or personality. But for the past hundred years people have always made out that he always judged his contacts rigidly as though the complex physics of emotion had no sway over him. Such a view is not that different from that which guided Qianlong’s compilation of Biographies of Those who Served Two Dynasties. [As Qian Zhongshu wrote,] ‘You don’t end up with a true account of the person or past events, for you need to empathise. You needs must place yourself in that context, imaginatively engage with the heart-mind of the past, feel it, sense it, be intimate with it.’[26]《老子》和《莊子》等等倒是也讀過,可是哲學類讀得少,更談不上有心得。至於歷史上的大問題,研究得也不多,我不研究大問題,所以只是對有些事情多少也有些看法就罷了。比方敦煌王道士的可惡之處到底是什麼,我認為並不是他由於無知以近乎於白送的價錢把經卷給了斯坦因,而是他得到錢之後很虔誠,也很辛苦地覆蓋了那些線條舒美,技法嫻熟,用筆流暢,但是因年代有所風黃雨損的壁畫和造像,給我們修復出了一大堆粗鄙、笨拙、俗艷的垃圾。比方顧亭林,他晚年擇友實際上不僅考慮政治操守,也考慮文化認同和性習相近,可是近百年來只要說到他的為人和交誼,總是用操守這把尺子比量,對複雜糾纏的人情物理乾脆視而不見,如此闡釋與乾隆朝修《貳臣傳》是殊途同歸,不合追敘真人實事,每須遙體人情,懸想事勢,設身局中,潛心腔內,忖之度之,以揣以摩之法。

We are surrounded by modern gadgets, so it’s even more important to preserve the world of the past in our lives. Of course, computers are good; they save time and effort. But there’s nothing like writing a letter with a calligraphic brush on traditional letter paper to an elder or friend. How could an email suffice? When I want to thank someone for their hospitality, I write out the ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems’ in my small regular calligraphic script.[27] It’s the traditional way. Inviting someone out in return is all a trifle too modern and practical, don’t you think? In short, you need to have a sense of what you are prepared to do and what you are not. It’s not hard to do what you want to do; it is difficult to avoid doing what you don’t. But even if it’s difficult, it’s not impossible. As long as you have your health you can follow the ways of the ancients. Take lodging in a temple when you are travelling, for example. It’s what the literati have done from ancient times. It might appear to be a difficult thing to do it these days. You aren’t a monk who’s allowed to stay in temples while on the road; nor are temples supposed to function as hotels. How do you get away with such a thing? In my desire to share the experience of my forebears, however, I’ve passed the night in over twenty temples. If you really want to emulate the ancients, you can find a way. 先進的東西在我們周圍已經很不少了,所以生活上還是保留些舊趣會更好。比方電腦好,省時省事,可是信件還是要用毛筆寫在八行箋上,尤其與長輩及友朋的通信,怎麼能用電子郵件呢?比方朋友間酬答我是送扇面,扇面上的字是我的小楷蘭亭序,古風交誼,應酬就是吃飯未免太先進太實在了吧。簡單說就是有所為有所不為,有所為不難,有所不為不易,雖然不易,也不是不能辦到。只要身體力行,按古人之法行事,都是能夠辦到的。比方寄寓寺廟是自古以來的一種文人風習,這事情當下好像不好辦,不是遊方掛單的和尚,寺廟又不是旅館,您憑什麼啊?可是我為了體驗古風在二十幾個寺廟寄寓過,您是躬身效法古人的實踐者,就能辦得到。

Put simply, I’ve never been in their sights; I’ve kept just out of range. That’s why my study is called the ‘Out of Range Studio’ 彀外書屋.[28] My book armoire dates from the Qing dynasty, and the bookcases are from the Republican period. On my desk I have my brushes, slabs of ink, paper and an ink stone.[29] On the wall I have a fan-face with calligraphy by Ji Xiaolan[30] and my grandfather’s hand-copied version of the ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems’. There is a curtain on the window and a reed blind on the outside. Many people are surprised that I could somehow get away with what I did during the topsy-turvy era of the Cultural Revolution and the Education Revolution. They say that ‘when the bird’s nest is overturned all the eggs inside shatter’.[31] But I never appeared on their radar. My life has been spent out of range, off the radar; it’s possible not to be a target, even in the midst of great upheaval. 簡單說也就是我這個人一直不在彀中而在彀外吧。書房就叫彀外書屋,書櫥是清的,書櫃是民國的,桌上是筆墨紙硯,牆上是紀曉嵐的扇面和我祖父臨的蘭亭序,窗戶裡面有窗簾,窗戶外面有葦簾——不少人根據覆巢之下豈有完卵的道理對一個人能夠置身於文化革命和教育革命之外有所懷疑,其實我只是在彀外而已,我的一生都不在彀中而在彀外,亂世也還是有可能置身彀外的。

Translator’s Notes:

- My thanks to Linda Jaivin for her stylistic and editorial suggestions.

[1] Hang, from bai hang 白珩 (also pronounced ‘heng‘), part of a jade ornament in pre-dynastic times, often a horizontal jade piece, though sometimes it was made in the form of a ring. The word appears in the Guoyu 國語, a collection of accounts of various states from roughly 1000 to 450 BCE compiled in the Western Han dynasty. The reference to hang occurs in an account of the State of Chu 《國語 · 楚語下》: 趙簡子 鳴玉以相,問於 王孫圉 曰:楚 之白珩猶在乎。韋昭 注:珩,珮上之橫者。

[2] The line in the original reads, 手挼六十花甲子,循環落落如弄珠。 It is a quotation from the Tang poet Zhao Mu, ‘Drinking Wine in Company’:

趙牧《對酒》

雲翁耕扶桑,種黍養日烏。

手挼六十花甲子,循環落落如弄珠。

長繩系日未是愚,有翁臨鏡捋白須。

飢魂吊骨吟古書,馮唐八十無高車。

人生如雲在須臾,何乃自苦八尺軀,

裂衣換酒且為娛,勸君朝飲一瓢,夜飲一壺。

杞天崩,雷騰騰,桀非堯是何足憑。

桐君桂父豈勝我,醉裡白龍多上升。

菖蒲花開魚尾定,金丹始可延君命。

[3] 平淡良善懂生活的人。 Pingdan 平淡 is a term with a long history related to the art of living and the individual pursuit of an untrammelled and refined existence.

[4] 究天人之際, 通古今之變。 From Sima Qian 司馬遷, ‘Letter to Ren An’ 《報任安書》 in his Records of the Historian 史記 (first century BCE), translated by J.R. Hightower and reproduced in John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, Classical Chinese Literature, An Anthology of Translations, New York: Columbia University Press/Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2000, vol.1, p.581.

[5] 孟元老撰《東京夢華錄》。

[6] Xi Kang (嵇康, also Ji Kang, 223-262 CE). One of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢 who were, as Jacques Gernet writes, ‘a little group of Bohemian literati, the best known of whom is the poet and musician Xi Kang.’ The temper of the times encouraged among the lettered men of an era of political turmoil ‘nonconformist attitudes — contempt for rites, free and easy behaviour, indifference to political life, a taste for spontaneity, love of nature.’ Indeed, ‘Independence and freedom of mind, a horror of conventions, a passion for art for art’s sake are characteristic of the whole troubled age from the third to the sixth century.’ See Gernet, A History of Chinese Civilization (1982), quoted in Minford and Lau, Classical Chinese Literature, An Anthology of Translations, vol.1, p.444. For the significance of Xi Kang to China Heritage, see Geremie R. Barmé, On Heritage 遺.

Two famous accounts of Xi Kang’s appearance, and one related to his uncompromising death, are given in Liu Yiqing’s 劉義慶 A New Account of Tales of the World《世說新語》, compiled c.430 CE:

Solitary Pine

Xi Kang’s body was seven feet eight inches tall, and his manner and appearance conspicuously outstanding. Some who saw him sighed, saying ‘Serene and sedate, fresh and transparent, pure and exalted!’ Others would say, ‘Soughing like the wind beneath the pines, high and gently blowing.’Shan Tao said, ‘As a person Xi Kang is majestically towering, like a solitary pine tree standing alone. But when he’s drunk he leans crazily like a jade mountain about to collapse.’

The Melody Is No More

On the eve of Xi Kang’s execution in the Eastern Marketplace of Luoyang (in 262), his spirit and manner showed no change. Taking out his seven-stringed zither (qin), he plucked the strings and played the ‘Melody of Guangling’. When the song was ended, he said, ‘Yuan Jun once asked to learn this melody, but I remained firm in my stubbornness, and never gave it to him. From now on the “Melody of Guangling” is no more!’ [廣陵散於今絕矣。]

— Translated by Richard Mather and quoted in

Minford and Lau, Classical Chinese Literature, vol.1, p.457.

[7] The first Qin emperor Shihuang 秦始皇 was infamous for having ‘burned books and buried scholars’ 焚書坑儒. Mao Zedong frequently referred to the Qin and jokingly observed that he and his comrades had outdone the first emperor many times over.

[8] 唐封演撰 《封氏聞見記》。

[9] Zhao Erfeng was also known as ‘Butcher Zhao’ as he ordered numerous executions during his official career. He was beheaded during the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, something Zhao Hang does not mention.

[10] 《清史稿》。 Prior to his work on Qing history in the Republican era, Zhao Erxun had been a late-Qing governor of the north-eastern three provinces. For the Qing History Project under the Communist Party today, see Zhao Ma, ‘Research Trends in Asia: “Writing History During a Prosperous Age”: The New Qing History Project’, Late Imperial China, vol.29, no.1 (June 2008): 120-145, at pp.121-122; and Geremie R. Barmé, China’s Prosperous Age (Shengshi 盛世), China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 26 (June 2011).

[11] A task carried out at the behest of Mao Zedong, who was obsessed with Chinese history. To work on the project the Zhao family was required to move to a secure residence in the compound of Zhonghua Publishers, Courtyard Number Two, Cuiwei Road, Beijing.

[12] ‘The Great Learning’ 大學 is one of the Four Books of Confucianism. As Zhao says, quoting the text, ‘讀書要修身、齊家、治國、平天下’.

[13] ‘Scholar-notebooks’ or ‘note-form literature’ 筆記, are collections of succinct, casual essays, or short records by writers and scholar-bureaucrats that cover a myriad of topics ranging from personal jottings to formal historical accounts and anecdotes. Zhao’s home schooling and taste in reading were completely at odds with the education his generation was receiving in a system dominated by the Communist Party and one which increasingly emphasized the importance of politics and class struggle.

[14] 《古文觀止》, an anthology for students first published in 1695. The expression ‘ultimate vision’ 觀止 in the title refers to an incident in the ancient text Zuo Zhuan 《左傳》 (Duke Xiang, Year 29) where the ruler says that a performance on one occasion was so superlative that no future performance would be worth looking at — this was the ‘last sight’ or ‘ultimate vision’. The Ultimate in Classical Prose is still used by teachers in the Chinese world and numerous texts from it have been translated into various European languages.

[15] 玩兒: a difficult word to translate given that it relates back to the scholar-bureaucrat tradition in which it means to pursue something seemingly with light-hearted delight while in fact finding in it the expression of an unfettered, although meticulously trained, artistic soul. Today, it generally means ‘to have fun’.

[16] Fu-jen University was built on the grounds of Prince Tao’s Mansion 濤貝勒府. For details and an aerial image of the former mansion, see Sang Ye and Barmé, Hidden Mansions: Beijing from the Air (Part I) in China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 16 (December 2008).

[17] Yung Wing (Rong Hong 容閎, 1828-1912) was the first Chinese student to graduate from an American college, Yale, after attending the Morrison School for Boys, named after Robert Morrison (1782-1834), a protestant missionary who translated with assistance and published the Bible in China. Yung worked with the Qing court to establish the Chinese Educational Mission that saw young Chinese sent to America for education from the late-Tongzhi reign period (1870s). For the full text of Yung Wing’s memoir, see the ‘Transcribed Texts’ section of the Yung Wing Project, founded by Cassandra Bates.

[18] 錢大昕撰《十駕齊養新錄》or Qian Daxin’s Record of Nurturing the New from the Studio of Tireless Pursuit and his 《廿二史考異》Researches into Anomalies in the Twenty-two Histories, 王鳴盛撰《十七史商榷》or Wang Mingsheng’s Disputations on the Seventeen Histories and 趙翼撰《廿二史剳記》 or Zhao Yi’s Notes on the Twenty-two Histories and 《陔余叢考》.

[19] 革命大串連。

[20] In the original, 讀萬卷書之后行萬里路。

[21] Tai Shan in Shandong province. For Du Fu’s poem, translated by David Hawkes, see, Minford and Lau, Classical Chinese Literature, vol.1, p.769. The original reads:

杜甫《望岳》

岱宗夫如何,齊魯青未了。

造化鐘神秀,陰陽割昏曉。

蕩胸生層雲,決眦入歸鳥。

會當凌絕頂,一覽眾山小。

[22] Li Sixun (李思訓, 651-?715) was an artists and a member of the Tang dynastic family. He is celebrated famous for landscape paintings executed in what is known as the ‘gold-and-green manner’ 金碧山水.

[23] From Zhang Ji, ‘A Night-Mooring near Maple Bridge’:

While I watch the moon go down, a crow caws through the frost;

Under the shadows of maple-trees a fisherman moves with his torch;

And I hear, from beyond Suzhou, from the temple on Cold Mountain,

Ringing for me, here in my boat, the midnight bell.

張繼《楓橋夜泊》

月落烏啼霜滿天,

江楓漁火對愁眠。

姑蘇城外寒山寺,

夜半鐘聲到客船。

— Translated by Witter Bynner. See Minford and Lau,

Classical Chinese Literature, vol.1, p.852.

[24] In the original: 挑燈研墨聯袂繪丹青。

[25] The ‘devil chaster’, Zhong Kui 鍾馗。

[26] Gu Tinglin 顧亭林, also known as Gu Yanwu (顧炎武, 1613-1682), was a philologist and famous for his resistance to the Manchu-Qing dynasty that replaced the Ming in 1644. He was also a critic of Neo-Confucianism. The quotation from Qian Zhongshu comes from his Pipe and Awl Collection 《管錐編》, first published in 1979.

[27] At a gathering of friends during which poems were exchanged at the time of the Spring Lustration Ceremony of 353 CE, Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 309-c.365) wrote a ‘Preface to the Orchid Pavilion Poems’ 《蘭亭集序》 at the Orchid Pavilion in Guiji near present-day Shaoxing, Zhejiang province. Wang is renowned as the greatest of Chinese calligraphers and his short preface, although existing only in copies, is exalted as a masterpiece of calligraphic art. See Duncan Campbell, Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations in China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 17 (March 2009) and Barmé, Spring Lustration 脩禊 — a pavilion, a calligrapher and eternity, China Heritage, 29 March 2017.

[28] 彀 means ‘target’, or ‘in the field of fire’. It can also mean a fully drawn bow.

[29] 筆墨紙硯, the ‘for precious things of the scholar’s studio’ 文房四寶, essential for literary composition, calligraphy and painting.

[30] Ji Xiaolan (紀曉嵐, Ji Yun 紀昀, 1724-1805), famous for his collections of ghost tales, and his more serious endeavour of co-editing the magnum opus of Qing collation, The Complete Library in Four Branches 《四庫全書》.

[31] 覆巢之下豈有完卵 also 覆巢無完卵. A saying from Liu Yiqing’s A New Account of Tales of the World relating to the tragic fate of Kong Rong 孔融. See Note [6] above.