Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter IV, Part II

義憤

My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice.

— George Orwell

It is because they had read him that the left thought they should hate Orwell; whereas by not reading Orwell, the right could convince themselves they loved him.

— Simon Leys

In Simon Leys on George Orwell in 1984 — we featured ‘Orwell: The Horror of Politics’, an essay composed by Pierre Ryckmans in 1983, and commented on its reception in Beijing in 1984. Here we pursue the topic of Leys-Orwell under the rubric of chagrin, a term that can can also translated as ‘indignant’ and ‘indignation’, 義憤 yì fèn in Chinese.

After a consideration of chagrin/indignation introduced by a quotation from The Man Who Got It Right, by Ian Buruma, we feature a video clip from an episode of Apostrophes, a prime-time weekly talk show on French TV created and hosted by Bernard Pivot. Aired on 27 May 1983, ‘Intellectuals faced with the history of communism’ — the theme of the show that night — was most memorable for the encounter between Simon Leys and Maria Antonietta Macciocchi. I first heard about their exchange shortly after taking up my doctoral studies with Pierre Ryckmans/ Simon Leys in 1983; I later learned that it was also discussed with considerable relish within a small but well-informed circle of Chinese writers and intellectuals in Beijing.

For the details of that moment in post-Mao Paris, we draw on the record provided by Phillipe Pacquet in Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds. This is followed by two further essays on George Orwell by Simon Leys, the first from 2002 and the second from 2012.

In reproducing material that straddles thirty years, from 1983 to 2012, we also recall a more recent decade — the ten years since Pierre Ryckmans passed away in August 2014. I would also like to acknowledge with gratitude Ian Buruma, who invited me to write about Phillipe Paquet’s encyclopedic account of Pierre’s life and work.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 June 2024

***

Related Material:

- Kafka, Orwell, Kundera, Apostrophes, 27 January 1984

- Philipe Paquet, Simon Leys, celui qui dénonça Mao…, TV5Monde, 14 May 2016

- One Decent Man, 28 June 2018

- 鴨架湯 — It’s Time for Another Serving of Peking Duck Soup, Appendix XXXIX in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 12 March 2023

***

Contents

(click on a section title to scroll down)

***

On Chagrin

an editorial observation by Geremie R. Barmé

One conspicuous feature of the European Maoists in the 1970s was their obliviousness to actual conditions in China. The Chinese were discussed almost as an abstraction. Leys, who cared deeply about the Chinese, became a hate figure in Paris. I remember watching him on a French television chat show. The host, Bernard Pivot, asked him why he had decided to take on what seemed like the entire Parisian intellectual establishment. Leys replied with one word: chagrin—grief, sorrow, distress.

— from Ian Buruma, The Man Who Got It Right, New York Review of Books, 15 August 2013

***

Simon Leys on George Orwell in 1984 featured ‘Orwell: The Horror of Politics’, an essay written by Pierre Ryckmans in 1983, and we commented on its reception in Beijing in 1984. Here we pursue the topic of Leys-Orwell under the rubric of chagrin, a term that can can also translated as ‘indignant’ and ‘indignation’, 義憤 yì fèn in Chinese, which also means ‘moral outrage’.

‘Indignation’ runs like a thread through the work of decades. I remember, for example, the expletive-laden verbal fireworks whenever the Hong Kong-based writer and humorist Hsiao T’ung talked about the murderous decades of Maoism or the despoliation of his native city of Peking in the late 1979s; then there was simmering outrage of the editor-activist Lee Yee who warned his fellow inhabitants of the British colony about the dire consequences they would inevitably face as a result of the Sino-British negotiations in the early 1980s. The Beijing journalist Liu Binyan repeatedly challenged official corruption and complacency and there was the famous playwright Wu Zuguang’s fury over the Communist Party’s half-hearted attempts at de-Mao-ification, as well as the bitter sarcasm with which he targeted Hu Qiaomu, the Wang Huning of his day, during the 1987 purge. The astrophysicist Fang Lizhi expressed his resistance with clear logic and liberating humour. All too soon, on the night of 4 June 1989, the renowned literary translator Yang Xianyi, in a mood of heart-broken outrage, decried the Beijing authorities as ‘fascists’ on the BBC. Or there were Liu Xiaobo’s outbursts of exasperation, mockery and disbelief — regarding the spinelessness of Chinese intellectuals, the craven titans of the arts scene, Beijing politics, PRC foreign policy, the treatment of Tibet, and so on. Liu shared the grief and ire of Ding Zilin and the Mothers of Tiananmen. It was indignation, too, that fuelled the historical muck-raking and environmental activism of Dai Qing, before, during and after her fall from grace; it similarly underpinned her steely independent political position when she faced opponents both inside or outside China.

Indignation and controlled moral fury motivated the heroic Geng Xiaonan in her tireless support, both emotional and material, for China’s shrinking community of conscience during the first years of the Xi Jinping autarky. Behind the mild manners and reasonableness of civil activists like the lawyers Xu Zhiyong and Ding Jiaxi smouldered an unrequited passion for justice. Similarly, indignation and well-honed outrage have been a constant in the life of Xu Zhangrun, a writer who is an embodiment of the old expression 義憤填膺 yì fèn tián yīng, ‘moral outrage swells in his breast’.

Professor Xu expressed his outrage with lapidary boldness:

老子不服,老子不怕

I will not submit,

I will not be cowed.

My own slow-burn fellow-feeling of chagrin is stoked by half a century in the company of these friends. It has been further renewed by my distaste for the self-serving Kumbaya smugness of others and the moral corruption of Stalino-Maoist Second Chancers — milksop Marxists and tenured radicals — in the academy, both in China and overseas. Added to that, is the vile drift of inhuman populism and folderol spouted by opportunistic conservatives about their imagined Greco-Roman/ Judeo-Christian ‘West’.

Of course, one recognises the complex, contradictory demography of the Silent Majority, as well as what I call The Other China. Swathes of everyday individuals, including writers, academics and intellectuals who, both due to necessity and as a result of personal proclivity, who persist or who choose to burnish their skill of self-preservation (see, for example, The Art of Survival in the Age of Xi Jinping). However, a quiet demeanour and soft-spoken reason often disguise a steely spirit of decency.

In Simon Leys on George Orwell in 1984, I noted Qian Zhongshu’s admiration for the outspokenness of Simon Leys, his exposé of Maoist China and his essay on George Orwell. For his part, Leys applauded Yang Jiang, Qian’s wife, and her Cultural Revolution memoir, which I had translated. Writing about it, he said:

Yang Jiang’s exquisite art certainly had no need for official recognition. Yet the Communist authorities saw fit to commend her achievement solemnly; they extolled it as an example to follow, as (in their own words) her book ‘shows a wound, yet utters no complaint’. Indeed. This last stroke brings irresistibly to mind one of the most bitterly Chinese of all political anecdotes:

In the Tang dynasty, the younger brother of an official prepares to leave for his first posting. He promises his elder brother that he will be utterly circumspect and patiently obedient in all his dealings with his superior: ‘If they spit on me, I shall simply wipe my face without a word.’ ‘Oh, no!’ replies the elder brother, terrified. ‘They might take your gesture for an impudence. Let the spittle dry by itself.’ This utterance has entered the common language as a proverb (tuo mian zi gan [唾面自乾]); it describes a reality that remains very much alive today, and Yang Jiang’s quiet smile can provide one of its latest and most heartbreaking illustrations.

[Note: For details, see June Fourth 2024 — Dai Qing, a Former Person who Refused to be Silenced, 4 June 2024.]

***

His subject-matter will be determined by the age he lives in – at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own – but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, or in some perverse mood: but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. …

The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one’s political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.

— George Orwell, Why I Write, summer 1946

An excerpt from the televised exchange between Simon Leys and Maria Antonietta Macciocchi, Paris, 27 May 1983

***

I think fools say foolish things. Just like apple trees produce apples. It’s in their nature, it’s only normal. The problem is that there are readers who take them seriously… Take the case of Madame Macciocchi, for example. I have nothing against Madame Macciocchi personally, I’ve never had the pleasure of getting to know her. When I speak of Madame Macciocchi, I’m speaking of a certain idea of China. I’m speaking about her work, not her person. Her book On China — the most charitable thing we can say [about it] is that it’s a total piece of stupidity, because if we don’t accuse it of being stupid, we’d have to say it’s a con.

— Simon Leys, Apostrophes, 27 May 1983

***

The Man Who Was Indignant

Phillipe Paquet

The publication in France of La Forêt en feu [The Burning Forest], but also of Yao Ming-le’s controversial book on the death of Lin Biao (Mao’s deposed heir apparent), referred to above in relation to Leys’s preface to the French edition at Robert Laffont, earned the Belgian sinologist an invitation to take part in the televised book show Apostrophes. Не received the invitation on 3 May 1983. On 23 May, he was in Paris. It was his first time on French television and Bernard Pivot, the illustrious host, announced all the more proudly that it hadn’t been easy to organise, since the author of The Chairman’s New Clothes was loath to make the long trip from Australia, especially as it meant wrestling in Paris with the followers of Maolatry, who hated him and whom he despised. Pivot wound up overcoming Leys’s reluctance, though, by arguing that as ‘the precursor’, as the one who had been the first to denounce the Maoist madness, he had ‘a duty to bear witness’. The show that went to air on 27 May 1983 left no one indifferent: not the presenter, not the participants, not the viewers — and not the publishers and booksellers either.

It was not the first time Apostrophes had looked at Mao’s China. Five years earlier, on 6 January 1978, Pivot had brought face to face, on his set, the diplomat Étienne Manac’h, who had been French ambassador to the People’s Republic of China between 1969 and 1975; the foreign correspondent for Le Monde, Alain Bouc; Claudie and Jacques Broyelle, the reformed Maoist couple back home from a second, twenty-month stint in Peking; Dr Georges Valensin, the author of a book on ‘sex life in communist China’; and Michelle Loi, the translator of Lu Xun whom Ryckmans had slated in ‘L’oie et sa farce’. The theme of that show was ‘living in China’, but after listening to such incredibly divergent testimonies, Pivot was driven to ask if all these people had really lived in the same country. Apart from Valensin’s gutter sexology and barrack-room reflections, the highlight of the evening was incontestably the clash of arms between the Broyelles and Michelle Loi. Reporting on it in Le Monde the day after, Jean de la Guérivière remarked presciently that the presence of Simon Leys would doubtless have livened up the debate even more. The May 1983 show was to prove him right.

For this new debate, which he’d called ‘Intellectuals faced with the history of communism’, in addition to Leys Pivot had invited three panellists who were as different as chalk and cheese: Jean Jérôme, otherwise known as Mikhaël Feintuch, the covert head of the French Communist Party, who had just brought out his memoirs, Jeannine Verdès-Leroux, a sociologist and historian who was promoting her monumental study Au service du Parti. Le parti communiste, les intellectuels et la culture (1944-1956), and Maria Antonietta Macciocchi, the militant passionara who had become a member of the European Parliament and who, twelve years after her famous Della Cina, a deluded and delusory account of her pilgrimage to the land of Maoism, had come to present an autobiography whose title alone, Deux mille ans de bonheur (Two Thousand Years of Happiness), already revealed itself to be particularly unfortunate.

Stupid Apple Trees

Born on 23 July 1922 into a bourgeois Roman family hostile to fascism, for twenty years Macciocchi subscribed to the Italian Communist Party (Partito Communista Italiano: PCI), which was then an underground group, while she was studying literature. After the war, she threw herself into journalism, running the women’s publications put out by the PCI, before becoming the foreign correspondent for L’Unità in Algiers, and then in Paris. Elected deputy for Naples in 1968, she soon fell out with the heavyweights in the party who didn’t particularly share her unconditional admiration for Chinese communism. A report filed for L’Unità in the middle of the Cultural Revolution provided her with the material for Della Cina, which, translated into several languages, became the cult book of European Maoists. ‘Macciocchi’s courage and lucidity in the quasi-general blindness’, was hailed by Philippe Sollers, who had persuaded Claude Durand at Le Seuil to see to its publication in French; the translation came out a few months before The Chairman’s New Clothes, and the Italian returned the favour by facilitating the famous Tel Quel trip to China in the spring of 1974. At odds with the PCI, Macciocchi moved to Paris, where she got a job at the Université de Vincennes. Elected to the European Parliament in 1979 under the banner of the radical party, she joined the socialist party — François Mitterrand gave her the Légion d’honneur in 1992. Until her death, on 15 April 2007, she led a frenetic life as a journalist and writer.

If the contributions of Jérôme and Verdès-Leroux were not lacking in interest, it was the tussle between Leys and Macciocchi on the set of public tv station Antenne 2 that was etched in people’s memories. This was the first time the two had met, but the Belgian sinologist had already said exactly how lowly he rated ‘the Italian lady of good works… complete with interpreter, Kodak, and notebook’ in Chinese Shadows. Commenting on Della Cina, he wrote:

I find her book somewhat abstract. She could have written in Europe, without leaving her room, if she had had some issues of Peking Review at her disposal; she would have gotten the same results. Her China experience was limited to a visit of a few weeks, and to three dozen interviews. You don’t discover by interviewing what people think, what they feel, what makes up the real fabric of their lives.

The first of the panel to be questioned on the show, Macciocchi didn’t seem to recall that criticism when she attempted to justify, absolutely shamelessly and without denial, her Stalinist, then Maoist, militantism. ‘Needless to say, my life was extremely chaste, all pure devotion. Saints get off on God; I got off on the people, on their redemption, which is what I was fighting for. I sacrificed myself day and night, she proclaimed, likening her political engagement to a religious vocation. Leys pitched his reply in ethical terms and, when Pivot asked him why he had suddenly given up the harmony of Chinese culture to throw himself into combative books, he answered with a single word: ‘Indignation’ [chagrin].

The rest of the debate proved that the word hadn’t been chosen at random. ‘At the precise moment that Simon Leys took the floor, I felt that something unheard of and powerful was about to happen on the set of Apostrophes that would shut us up for a good while’, Pivot noted in his ‘Carnets’ in the magazine Lire. Leys ‘spoke with the conviction and authenticity of a man who is indignant. Profoundly indignant. Longstandingly indignant. Dignifiedly indignant. And even if he’d wanted to be courteous, he wouldn’t have been able to stop his indignation from bursting out.’

“That’s the only time I’ve seen a guest indignant,’ Pivot told me some thirty years after the event. Having gone there to denounce the imposture of the Mao worshippers of the West, of whom Macciocchi was a caricatural incarnation — ‘the height of caricature’, as Gérard Chaliand was to say, and he knew what he was talking about — Leys was to show himself implacable, firing shots that hit a bullseye every time and provoked both laughter from the audience on set and complicit smiles from the presenter — notably, this memorable barb:

I think fools say foolish things. Just like apple trees produce apples. It’s in their nature, it’s only normal. The problem is that there are readers who take them seriously… Take the case of Madame Macciocchi, for example. I have nothing against Madame Macciocchi personally, I’ve never had the pleasure of getting to know her. When I speak of Madame Macciocchi, I’m speaking of a certain idea of China. I’m speaking about her work, not her person. Her book On China — the most charitable thing we can say [about it] is that it’s a total piece of stupidity, because if we don’t accuse it of being stupid, we’d have to say it’s a con.

Leys then got stuck into the book, debunking its two main theses. The first proclaimed that ‘Mao’s people is humanity without sin’. It wasn’t really clear who had saved it from sin, but presumably it was Mao. From that flowed ‘quite normally facts that Madame Macciocchi notes with wonder: in China, the workers reject wage increases and feel trade unions are superfluous; the peasants practise philosophy and Mao’s thought makes peanuts grow’. The second axiom postulated that Maoism was a break with Stalinism. Pulling out of his jacket pocket a scrap of paper on which he’d jotted down quotes from Mao, Leys demonstrated not only that the Chinese continued to praise Stalin after adopting his methods (a fact revealed by the existence in China, as in the USSR, of gulags), but they had even taken Stalinism to new heights:

In private, Mao expressed certain reservations about Stalin. He found Stalin killed too many people, he killed for the sake of it and in a way that was basically inefficient, whereas he, Mao, killed efficiently. Between 1950 and 1952, in China, the greatest specialists put the number of political executions at five million, based on extrapolations from documents belonging to the Chinese Communist Party itself.

Divine Wrath

Macciocchi couldn’t believe her ears. She had been prepared not only to have a nice time that evening, but also to enjoy fresh accolades from the media; she’d even told the other guests, with disarming arrogance, that ‘the important book, that evening, was hers’. Of course, she had been somewhat nervous at the idea of debating three authors who, given their profiles, would necessarily join forces against her. But Bernard-Henri Lévy, ‘who had looked after my book’, had set her mind at rest, reassuring her that ‘viewers are always on the side of the person under attack’. Instead of which, she would later recall taking part — under a hail of applause from the crowd — in an execution: hers.

I’m watching the stage as you do in the theatre when the curtain goes up. The sinologist, in his role as public prosecutor, his whole body shaking with a mysterious tremor caused by a sort of divine wrath (stored up for ten years) that galvanised Pivot, immediately brought accusations against me, without beating about the bush: ‘Your book on China is extremely cretinous, it’s a fraud. You are complicit in the death of untold numbers of Chinese’ … Pivot, extraordinary television animal and consummate professional that he is, looked as if he was really struck by the truth-violence conveyed by the sinologist. A sort of stupor hovered over the show. Leys gave free rein to his indignation, without even trying to tone down, as is done out of politesse, the insulting adjectives.

Macciocchi implored Pivot to put an end to the torture by demanding they talk not about a book published in 1971, but about the one that had just come out. Fatal mistake, for Leys took advantage of it to deal the death blow, singling out the peculiar place this autobiography gave precisely to the Chinese career of its author.

The chapter De la Chine (‘On China’) in Deux mille ans de bonheur deals with Paris society. There are little sexual romps, there are love affairs, there are Paris salons, etc. China vanishes from the horizon and we realise that China has never meant anything to you except as an excuse to have fashionable conversations in Paris salons. The day it goes out of fashion, well, China no longer exists, and a billion men dip over to the other side of the horizon; we don’t talk about them anymore, we don’t see them anymore. We talk only about Monsieur Sollers and other equally grotesque characters.*

[Author’s Note: * In ‘Sur la Chine’, in La Forêt en feu (p. 170), Leys wrote: ‘Were the Chinese, then merely 900 million supernumerary extras, mobilised just to lend support for a moment to the fairground parade of a few Parisian egos?’]

And in case one last banderilla needed to be thrust into the bull’s neck, Leys planted it, attacking the book’s most eloquent ‘stupidity’: its title. Macciocchi had explained the meaning of the title earlier in the show, referring to the good wishes Mao had allegedly addressed to her when he welcomed her in Peking.

Incidentally, Mao Zedong could never have wished you two thousand years of happiness, neither you nor Chinese women, because the expression doesn’t exist in the Chinese language, it doesn’t even exist in Hunan dialect [which was Mao’s dialect]. That is the most venial of your sheer fabrications compared to the whoppers to be found elsewhere in your book.**

[Author’s Note: ** Macciocchi continued to deny any misinterpretation on her part (despite the fact that the Chinese always say ‘ten thousand years’): ‘That is exactly the phrase Mao said to me, a Western woman, but more than that, those two thousand years of the title were transformed in the tale into a symbol of the shift from oriental time to the time of our Christian civilisation. During a trip to Jerusalem, I came across Mary’s traces, two thousand years old, a sort of synthesis of the history of women.’ La Femme à la valise, op. cit., p.188; the emphasis is Macciocchi’s.]

When the show was over, Macciocchi took off without further ado. And without having a drink with the other participants, unlike Jean Jérôme who, even though he’d also come in for some rough treatment, forced himself to put on a brave face till the end. The Italian never got over the humiliation which, Jeannine Verdes-Leroux estimated, ‘changed her view of the Parisian world.’

‘Thinking about it again today with a cool head, it was the sole trial celebrated live in Paris against the 1970s Maoists, the hyper-Marxist Maoists who had so resoundingly marked that era,’, Macciocchi in fact wrote in a new autobiography published in Italian four years later:

But the sad thing was that none of them were around anymore. Only a single accused remained, a woman and a foreigner. A dame italienne, as Simon Leys called me. This first phase of the operation was, however, followed indirectly by a second, which tended to deflect attention from the Maoist fury of Paris intellectuals — who had slyly turned their coats anyway. Where were — I asked myself, as I was shot down in flames — Serge July, Sartre, Glucksmann, Philippe Sollers and Kristeva, Althusser and Badiou, not to mention Alain Peyrefitte and Roland Barthes, early version? And Alberto Moravia, with his traveller’s tale, heralding the Wests intellectual love affair and translated into several languages? He, too, had disappeared. In Paris, in France, Europe, on the whole planet, at that soirée organised by Apostrophes, there was only one survivor of universal Maoism: the dame italienne… Why didn’t I get up and leave, slamming the door behind me? Why did I agree to sit there, sinking into this anguish, into a terror that turned into paralysis? Because I just couldn’t believe it, I felt like I was in a parody of one of those internal communist party trials, in the famous cell meetings (and I’d sat through more than one). And because, for me, Apostrophes represented the last bastion of cultural freedom.

An Unsellable China

Ten years after appearing on Apostrophes, Maria Antonietta Macciocchi ran into Bernard Pivot in Rome, and she told him again that that experience had annihilated her, that she’d never recovered from it, that she had unjustly paid for all the others, the Barthes, the Sollers, etc. If she is to be believed, the tape of the show was reproduced by the hundreds and sent by mysterious hands all over Europe, including to people in high places, in order to discredit and ridicule her. She, the unfortunate dame italienne, had only one weapon to use against this odious and insidious undermining, and that was ‘her one small truth: she had loved China, that society of the poor that was reaching for the skies, an evangelical China, a metaphysical entity’. For her, ‘Mao remained basically an educator, a revolutionary intellectual, the legendary liberator who had extricated China from colonialism’.

Apostrophes had unexpected and unprecedented consequences for Macciocchi and her French publisher, Grasset. The cult show, which at its peak captured some three millions viewers every Friday night, routinely catapulted sales of the books Pivot promoted so remarkably well, without the slightest hint of deference but by broadcasting his passion on set. For once, it was the reverse. In fifteen years of existence, Apostrophes had only had one memorable case of a below-par commercial performance, reports Daniel Garcia: that was the performance of Macciocchi, whose publisher ‘recorded only returns’. The book had become ‘unsellable’, Pivot confirmed. Sales had started off well, but as early as the Saturday morning, not a single copy sold, Jeannine Verdès-Leroux heard at Grasset.

The press, it’s true, were merciless after the show. Le Monde, even though it had given Deux mille ans de bonheur a positive review on its title page a few weeks earlier, published a humorous column of Bruno Frappat’s on the front page of the 29-30 May edition. ‘They tore each other to shreds, on Friday, on the show Apostrophes, over Stalinism and Maoism… The accusers, Mr Simon Leys for the Chinese side, Ms Jeannine Verdès-Leroux for the Stalinist side, had a field day, he noted, concluding: ‘Such is life for whoever lends their agile pen to the combats and certainties of the moment, which, over the course of the years, turn into mistakes that are hard to put right. There is such a thing as writers’ blunders’.

Simon Leys remembered being congratulated on the streets of Paris the day after the show by complete strangers. He was not to see the protagonists of that great moment of television again. Maria Antonietta Macciocchi, ‘guillotined’, vanished once and for all from the sinologist’s concerns. On the other hand, Pierre Ryckmans had ‘a very nice memory’ of Jeannine Verdès-Leroux, ‘an intelligent, sincere, well-informed woman’, and he kept up an exchange of letters with her for a while, before losing contact. ‘It was a stroke of luck that I had her with me in that encounter, which pitted us against two pretty unsavoury characters’, he told me. He similarly continued to feel friendly admiration for Bernard Pivot, while meeting Simon Leys made a strong and lasting impression on the latter. Twenty-eight years later, in Les Mots de ma vie, his autobiographical dictionary, the journalist made this extremely complimentary admission:

Simon Leys is the living writer I admire most in the world. His erudition, his lucidity (first intellectual to denounce the crimes of the Cultural Revolution), his courage (insulted, defamed by the numerous and influential French admirers of Mao), his talents as a sinologist, storyteller, historian, critic, translator, as a writer quite simply, his use of an elegant, precise, effective language, his modesty, his niceness, his generosity. The idea of sending a horribly banal, blatantly pointless letter to him, in Australia where he lives, paralyses me. And the idea that he might feel obliged to answer me, if he got it, makes me feel even more guilty. My silence is the most respectful form of my admiration.

***

Source:

- Philippe Paquet, Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds, 2017, pp.384-391, with minor modifications

***

Misfit by Conviction

Simon Leys

George Orwell particularly liked Hans Christian Andersen’s tale “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” but he remarked that Andersen did not have much psychological acumen: in real life, when a child has the cheek to say that the emperor is naked, he is instantly silenced with a good spanking.

Orwell spoke from personal experience: the brave honesty with which he had exposed the Stalinist betrayal of the Spanish republican cause earned him the rabid enmity of the leftist intelligentsia, which ensured that his firsthand testimony, the magnificent “Homage to Catalonia,” was first slandered, then strangled by a strict and tight conspiracy of silence—and then buried off (the original 1938 edition, a modest printing of 1,500 copies, was still half-unsold 13 years later).

Meanwhile, his “Animal Farm” had fallen foul of government censors who attempted to prevent its publication (“Animal Farm” eventually appeared in 1945 after 18 months of rejections and setbacks). Indeed, immediately after the war, political opportunism even led U.S. occupation authorities in Germany to seize and destroy the Ukrainian edition of the book. (It might have offended the Soviet ally!)

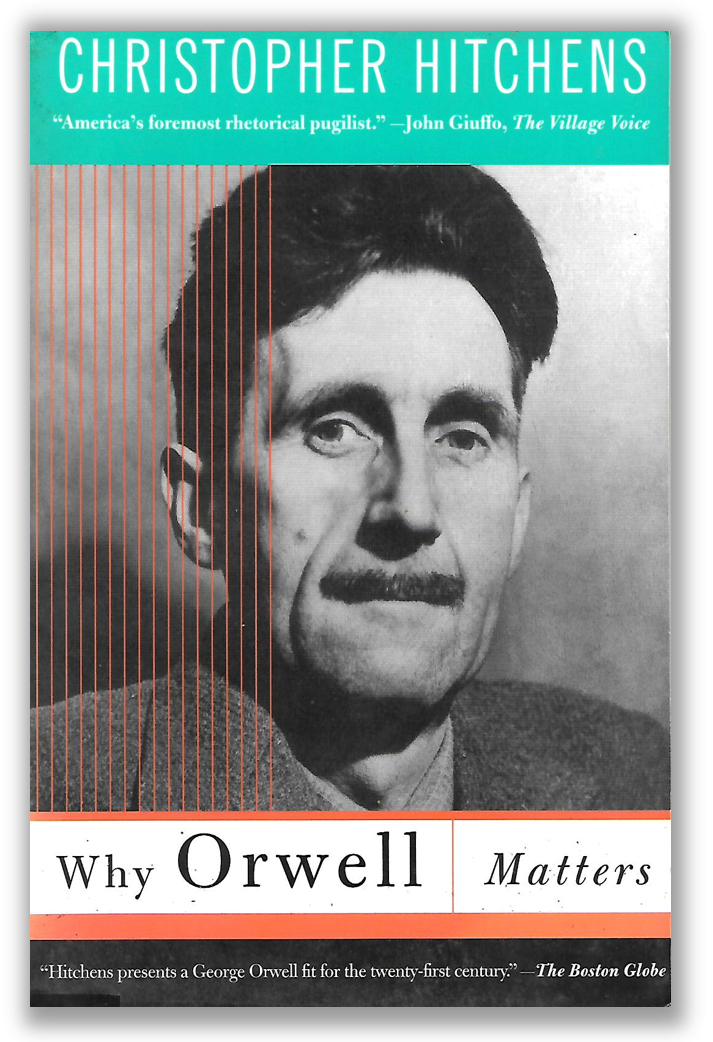

And finally—supreme indignity!—the very people against whom Orwell had battled during his journalistic career endeavored to appropriate “Nineteen Eighty-four” as ammunition for their own crusade; the stupidity of the progressive camp, which had failed to see that Orwell was in fact their greatest writer, enabled the reactionaries to press-gang his dead body under their own banner. It is because they had read him that the left thought they should hate Orwell; whereas by not reading Orwell, the right could convince themselves they loved him. The principal merit of Christopher Hitchens’ useful—though uneven and sometimes hasty—collection of articles resides in its documented examination of the paradoxes presented by Orwell’s posthumous fate.

In politics, the old divide between a brainless left and a heartless right was well captured by Emerson: “There is always a certain meanness in the arguments of the Conservatives combined with a certain superiority in their facts.” Orwell’s unique strength—and also his curse—derived from the fact that, even though his commitment to socialism remained unwavering, at the same time (and to the great distress of his comrades) he constantly maintained a certain superiority of the facts. He never allowed political dogma to encroach upon his sense of reality; this requires uncommon moral discipline, but in the end, he could truly say: “Where I feel that people like us understand the situation better than the so-called experts, it is not in any power to foretell specific events, but in the power to grasp what kind of world we are living in” (my emphasis). Naturally, such “power” was not likely to endear him to ideologues on his side of politics; as Hitchens shows, half a century later, they still have not forgiven him.

The driving force through Orwell’s adult life was his passion for justice. As a young man, he gave up his career in the Burmese Imperial Police out of disgust for all forms of bullying and oppression. This experience marked his political awakening: “I wanted to submerge myself, to get right down among the oppressed, to be one of them and on their side against their tyrants.”

It also set the pattern for his later political attitudes: though his rejection of imperialism and colonialism remained final and uncompromising, he was not blind to the complexity of their human and cultural dimensions. Witness, for instance, the rich ambivalence of his appraisal of Rudyard Kipling: “I worshipped Kipling at thirteen, loathed him at seventeen, enjoyed him at twenty, despised him at twenty-five, and now [in 1936, at the time of Kipling’s death] again rather admire him”—and he admired him for his “personal decency” and for his “sense of responsibility.”

When fighting against fascism, he retained this awareness of human ambiguity that cannot be reduced to ideological cliches. Jack London fascinated him (“Iron Heel,” which Orwell first read when he was 15, left a deep impression on his mind and, 30 years later, was to become a seminal influence upon the conception of “Nineteen Eighty-four”), but he also detected in London a strong fascistic streak.

Early in the war (1941), in a review of H.G. Wells, an author he considered “too sane to understand the modern world,” he invoked again, in contrast, the prescient intuition of “Iron Heel” (“a crude book” that is also “a truer prophecy of the future”) and, as a corrective to Wells’ myopic sanity, he again referred to Kipling, who was “only half-civilized” but, “not being deaf to the evil voices of power and military ‘glory,’ would have understood the appeal of Hitler, or for that matter, of Stalin.” Orwell was not blind to the flaws of figures such as London and Kipling, but he also saw that these very flaws afforded them “the power to grasp what kind of world we are living in.”

Human reality always transcends ideology. This perception is the key to Orwell’s integrity and originality, and it never left him, even in the heat of battle, as was well-illustrated in a memorable vignette from the Spanish front. One morning, as he went “to snipe at the Fascists in the trenches outside Huesca … a man jumped out of the trench and ran along the top of the parapet, in full view. He was half-dressed and was holding up his trousers with both hands as he ran. I refrained from shooting at him … partly because of that detail about his trousers. I had come to shoot at ‘Fascists,’ but a man who is holding his trousers isn’t a ‘Fascist,’ he is visibly a fellow creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t feel like shooting him.”

The pages Hitchens devotes to “Orwell and the Left” represent, I think, the most important chapter in his book. His inquiry into the poisonous hatreds that the memory of Orwell continues to arouse among the bien-pensants led him to unearth some very odd writings by (among others) Salman Rushdie and Edward Said. A century ago, Charles Peguy wondered what cowardly actions intellectuals would not be ready to commit out of fear of appearing insufficiently left-leaning. This observation is even more relevant today, and in its light, I guess Hitchens ought to be congratulated for his courage.

Of course, he dealt rather gently with “dear Salman,” but the fact remains: he dared to quote him and Said at great length—and one could not conceive of crueler treatment: Rushdie and Said stand in front of us, pilloried by their own prose. There is no space here to reproduce Hitchens’ lethal selection: readers should refer directly to his book. Suffice it to say, Rushdie criticized Orwell for his “quietism”; he found him guilty of following “an intrinsically conservative option,” advocating “a passivity which serves the interests of the status quo, of the people already at the top of the heap”; and he accused “Nineteen Eighty-four” of promoting “ideas that can only be of service to our masters.”

As everyone knows, Orwell risked his life for his ideas. He was grievously wounded by the fascists on the Spanish front and then narrowly escaped assassination by Stalinist thugs; he always lived off his pen, chained to the drudgery of freelance journalism in a state of permanent material insecurity. Yet Said’s criticism is even more outlandish than Rushdie’s. According to him, Orwell merely “observed” politics from the safe and cozy distance of a life spent in bourgeois comfort! And this reproach comes from a tenured American professor: Mt. Everest might as well begrudge a molehill its impudent height.

Whether it is justified, the credit enjoyed by Rushdie and Said is real enough; in compiling this amazing betisier, Hitchens accomplished a much-needed and salubrious task. His debunking of Claude Simon and of “post-modernist” critics, however, seems a waste of time and energy. As the Chinese proverb—invented by Jacques Maritain—says: “Never take stupidity too much in earnest.” (With the exception of three American scholars and seven Swedish academicians, who ever read Simon? In 1985, shortly before Simon received the Nobel Prize for literature, the French government, in a dastardly episode, sent its goons to sink the Rainbow Warrior in the port of Auckland. At the time, commenting on Simon’s award, a perceptive French literary critic wrote a piece that should remain the final word on the subject: He expressed the suspicion that, in retaliation, New Zealand had formed an axis with Sweden and just attempted to sink the French novel.)

Hitchens’ chapter on “Orwell and America” reminds me of Samuel Johnson, who once boasted that he could memorize one entire chapter from “The Natural History of Iceland,” titled “Concerning Snakes.” It went more or less like this: “There are no snakes in Iceland.” Orwell showed little interest in the U.S. and never visited the place. After the war, as England was severely rationed, he tried to obtain from America “a pair of shoes suitable for a large-footed man.” Whether or not this modest wish was granted is not known: It would have constituted one of his more significant transatlantic contacts.

On the subject of “Orwell and Englishness,” Hitchens contributes little that is new. At first, a parallelism with Philip Larkin seemed a promising theme, but Hitchens backs away from it on what seems irrelevant political grounds: “The whole repertoire of supposed Englishness and sentiments is a poor guide for questions of principle.” Yet, precisely, Englishness is not a question of principle and it has nothing to do with politics. The issue is visceral; it is perhaps the only topic on which Orwell ever comes close to waxing lyrical—or to displaying irrational feelings (such as his dislike of all things Scottish or his effusive celebrations of English cooking. Though he was not incapable of appreciating Continental cuisine, that he should still praise kippers and puddings seems to be pushing Englishness to the level of a willful perversity.) I wish I had space to quote in full the pages of poetic and emotional intensity in which he sang his love of England:

“When you come back to England from any foreign country, you have immediately the sensation of breathing a different air…. The beer is bitterer, the coins are heavier, the grass is greener …. The crowds in the big towns with their mild knobby faces, their bad teeth and gentle manners are different from a European crowd. [Note that, for Orwell, England is not in Europe.] Then the vastness of England swallows you up…. And the diversity of it, the chaos! The clatter of clogs in the Lancashire mill-towns, the to-and-fro of the lorries on the Great North Road, the queues outside the Labour Exchanges, the rattle of pintables in the Soho pubs, the old maids biking to Holy Communion through the mists of the autumn morning … , yes, there is something distinctive and recognizable in English civilization…. It is somehow bound up with solid breakfasts and gloomy Sundays, smoky towns and winding roads, green fields and red pillar-boxes. It has a flavour of its own. Moreover it is continuous, it stretches into the future and the past, there is something in it that persists, as in a living creature…. And above all it is your civilization, it is you. However much you hate it or laugh at it, you will never be happy away from it for any length of time. The suet puddings and the red pillar-boxes have entered your soul. Good or evil, it is yours, you belong to it, and this side of the grave you will never get away from the marks it has given you.”

But perhaps if Hitchens fails to appreciate the depth and significance of Orwell’s Englishness, it is because he himself is an Englishman. Fish are not in the best position to comment upon the wetness of water. (By the way—this is an irrelevant aside—when Hitchens mentions Jonathan Swift’s Houyhnhnms, why does he characterize them as “cynical and evil”? Then, would he also qualify Yahoos as sweet and peace-loving creatures? I am puzzled. Perhaps there is here some second-degree irony that, in my lack of sophistication, I remain incapable to “deconstruct.”)

“The List” is one of Hitchens’ shortest chapters but, for it alone, it would be worthwhile to buy his book. In a few incisive and well-documented pages, Hitchens sets the record straight on an ignoble episode which is still in all memories. In 1996, some indecrottables Stalinists launched a rumor that quickly spread under various versions and took root in international opinion. The object of the operation was to slander Orwell’s memory and destroy his moral credibility by creating the impression that sensational new evidence had surfaced revealing that Orwell, far from being a man of towering integrity, was a stool-pigeon who, at the beginning of the Cold War, supplied blacklists of Communists and fellow-travelers to the British Secret Service.

The impact of these “revelations” was stunning: As the Daily Telegraph put it, “it was as if Winston Smith had willingly cooperated with the Thought Police in ‘Nineteen Eighty-four.’ ” The calumny was too enormous; yet, for a while it succeeded because of its very enormity. “Keep lying, always keep lying,” Voltaire advised, “in the end something will stick.” Actually the “new evidence” was not new. The “facts” had already been evoked—without provoking scandal, for there was no cause for scandal—in Bernard Crick’s authoritative biography, published in 1990. There was no “blacklist,” since no one’s employment was ever at stake. The private information that Orwell communicated to an old friend (employed in foreign affairs) at her own request was as unimpeachable as any conscientious and honest referee report.

If Orwell’s sober and accurate assessment of a series of fellow intellectuals and writers can be deemed dishonorable, then, by the same token, any scholar who, in the normal course of his duties, comments honestly on the competence and suitability of potential appointees to academic positions in his own discipline should be considered guilty of much greater crimes.

The fact that nearly half a century after his death Orwell should again be the target of such vile attacks is a good measure of the formidable menace which, beyond the grave, he still presents for his cowardly enemies. Yet, as regards this particular maneuver, I think that Hitchens has put paid to it once and for all.

As Hitchens shows, the permanent relevance of Orwell rests on the fact that he clear-sightedly identified the issues that mattered and on each of them expressed independent, strong and sound views. Furthermore, what added weight to his ideas was his admirable capacity to vouch for them with his own life and actions.

This being said, the last page of Hitchens’ book leaves me dumbfounded. He concludes by referring to W.H. Auden’s famous verses “In Memory of W.B. Yeats”—“Time that with this strange excuse / Pardoned Kipling and his views, / And will pardon Paul Claudel / Pardons him for writing well”—lines that can be aptly applied to supreme artists who were also wretched individuals but inappropriate twice over when speaking of Orwell. For which sins indeed should Orwell be forgiven? And where does his art ever reach the sort of sublimity for which, as Auden suggests, the great sinners of literary history should be pardoned?

In order to express his ideas, Orwell developed a writing style that is supple, lucid and arresting, achieving the very perfection of journalistic readability. Yet, if we read him today, it is not for the aesthetic enjoyment of his style but for the tonic quality of his ideas.

The jarring note of Hitchens’ disconcerting conclusion is all the more surprising because he obviously knows and loves his subject. The American edition of his book carries a title which, in its straightforward simplicity, is in harmony with Orwell’s spirit. The original English edition, on the contrary, was awkwardly entitled “Orwell’s Victory.” In fact, the name Orwell and the word “victory” were once before joined in a title, but it was to convey precisely the opposite meaning. I refer to the moving memoir of Richard Rees, “George Orwell, Fugitive From the Camp of Victory.” Rees, who was one of Orwell’s few intimate friends, borrowed his superb title from Simone Weil: “… If we know in what way society is unbalanced, we must do what we can to add weight to the lighter scale and be ever ready to change sides like justice, ‘that fugitive from the camp of victory.’ ”

For Orwell, “misfit by conviction” (in the felicitous expression of John Carey), victory—like success and power and authority—was suspect by nature; he endorsed Arthur Koestler’s view that “all revolutions are failures.” He believed that “men are only decent when they are powerless”; he confessed “failure seemed to me the only virtue—every suspicion of self-advancement, even to ‘succeed’ in life to the extent of making a few hundreds a year seemed to me spiritually ugly, a species of bullying,” and again, “I never went into a jail without feeling that my place was on the other side of the bars.”

By any stretch of the imagination, I cannot picture what a triumphant Orwell should look like. Had he lived, could fame—and wealth—ever have altered him? One may doubt it. Shortly before his death, when it became obvious that “Nineteen Eighty-four” would become a major bestseller (a new experience for Orwell), he indulged for once in a luxury purchase; he never had the chance to make use of it, but it still provides us a valuable clue on how success might have affected his life: he bought a good fishing rod.

***

Source:

- Simon Leys, Misfit by Conviction, Los Angeles Times, 29 September 2002

***

The Intimate Orwell

Simon Leys

The intimate Orwell? For an article dealing with a volume of his diaries and a selection of his letters, at first such a title seemed appropriate; yet it could also be misleading inasmuch as it might suggest an artificial distinction—or even an opposition—between Eric Blair, the private man, and George Orwell, the published writer. The former, it is true, was a naturally reserved, reticent, even awkward person, whereas Orwell, with pen (or gun) in hand, was a bold fighter. In fact—and this becomes even more evident after reading these two volumes—Blair’s personal life and Orwell’s public activity both reflected one powerfully single-minded personality. Blair-Orwell was made of one piece: a recurrent theme in the testimonies of all those who knew him at close range was his “terrible simplicity.” He had the “innocence of a savage.”

Contrary to what some commentators have earlier assumed (myself included), his adoption of a pen name was a mere accident and never carried any particular significance for himself. At the time of publishing his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London (1933), he simply wished to spare potential embarrassment to his parents: old Mr. and Mrs. Blair belonged to “the lower-upper-middle class” (i.e., “the upper-middle class that is short of money”) and were painfully concerned with social respectability. They could have been distressed to see it publicized that their only son had led the life of an out-of-work drifter and penniless tramp. His pen name was thus chosen at random, as an afterthought, at the last minute before publication. But afterward he kept using it for all his publications—journalism, essays, novels—and remained somehow stuck with it.

All the diaries of Orwell that are still extant (some were lost, and one was stolen in Barcelona during the Spanish civil war, by the Stalinist secret police—it may still lie today in some Moscow archive) were first published in 1998 by Peter Davison and included in his monumental edition of The Complete Works of George Orwell (twenty volumes; nine thousand pages). They are now conveniently regrouped here in one volume, excellently presented and annotated by Davison. The diaries provide a wealth of information on Orwell’s daily activities, concerns, and interests; they present considerable documentary value for scholars, but they do not exactly live up to their editor’s claim: “These diaries offer a virtual autobiography of his life and opinions for so much of his life.” This assessment would much better characterize the utterly fascinating companion volume (also edited by Peter Davison), George Orwell: A Life in Letters.

Orwell’s diaries are not confessional: here he very seldom records his emotions, impressions, moods, or feelings; hardly ever his ideas, judgments, and opinions. What he jots down is strictly and dryly factual: events happening in the outside world—or in his own little vegetable garden; his goat Muriel’s slight diarrhea may have been caused by eating wet grass; Churchill is returning to Cabinet; fighting reported in Manchukuo; rhubarb growing well; Béla Kun reported shot in Moscow; the pansies and red saxifrage are coming into flower; rat population in Britain is estimated at 4–5 million; among the hop-pickers, rhyming slang is not extinct, thus for instance, a dig in the grave means a shave; and at the end of July 1940, as the menace of a German invasion becomes very real, “constantly, as I walk down the street, I find myself looking up at the windows to see which of them would make good machine-gun nests.”

To some extent, the diaries could carry as their epigraph Orwell’s endearing words, from his 1946 essay “Why I Write”:

I am not able, and I do not want, completely to abandon the world-view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue…to love the surface of the earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information.

Very rarely the diarist does formulate a sociopsychological observation—but then it is always strikingly original and perceptive—thus, for instance this subtle remark on a specified

discomfort inseparable from a working man’s life…waiting about. If you receive a salary it is paid into your bank and you draw it out when you want it. If you receive wages, you have to go and get them on somebody else’s time and are probably left hanging about and probably expected to behave as though paying your wages at all was a favour.

Then he describes the long wait in the cold, the hassles and expenses of journeys by tram back and forth to the paying office:

The result of long training in this kind of thing is that whereas the bourgeois goes through life expecting to get what he wants, within limits, the working-man always feels himself the slave of a more or less mysterious authority. I was impressed by the fact that when I went to Sheffield Town Hall to ask for certain statistics, both Brown and Searle [his two local miner friends]—both of them people of much more forcible character than myself—were nervous, would not come into the office with me, and assumed that the Town Clerk would refuse information. They said: “he might give it to you, but he wouldn’t to us.”

The writing of the diaries is terse, detached, and impersonal. I just wish to give here some space to one example—it is typical as it expresses both the drastic limitations of the form adopted by the diarist, as well as some remarkable features of his personality. It is the entry of August 19, 1947, dealing with the Corryvreckan whirlpool accident.

On the Hebridean island of Jura, in the solitary, spartan, and beloved Scottish hermitage where, in the final years of his life, Orwell spent most of his time—at least when not in hospital, for his failing health had already reduced him to semi-invalidity—he used a small rowing boat equipped with an outboard engine both for fishing (his great passion) and for short coastal excursions. Returning from one of those excursions with his little son, nephew, and niece, he had to cross the notorious Corryvreckan whirlpool—one of the most dangerous whirlpools in all British waters. Normally, the crossing can be safely negotiated only for a brief moment, on the slack of the tide. Orwell miscalculated this—either he misread the tide chart or neglected to consult it—and the little boat reached the dangerous spot exactly at the worst time, just in the middle of a furious ebbing tide.

Orwell realized his mistake too late; the boat was already out of control, tossed about by waves and swirling currents; the outboard engine, which was not properly secured, was shaken off its sternpost and swallowed by the sea; having steadied the boat with the oars and passed twice through the whirlpool, Orwell headed toward a small rocky islet that was nearby. The boat overturned just as it was being pulled ashore by his nephew, spilling its occupants and all their gear into the waves. Orwell managed to grab his son, who had been trapped under the boat, and he and his son and niece swam safely ashore. Perchance the weather was sunny; Orwell proceeded immediately to dry his lighter and collect some fuel—grass and peat—and soon succeeded in lighting a fire by which the castaways were then able somehow to dry and warm themselves. Having gone to inspect the islet, Orwell discovered a freshwater pool that he conjectured was fed by a spring of freshwater and an abundance of nesting birds. Under his unflappably calm and thoughtful direction the little party settled down without any panic. Some hours later, by extraordinary chance in such forlorn waters, a lobster boat that was passing by noticed their presence and rescued them.

Virtually nothing of this dramatic succession of events is conveyed in Orwell’s desiccated note: half the diary entry is devoted to naturalist observations on the islet puffin burrows and young cormorants learning to fly. To get the full picture, one must read the nephew’s narrative in Orwell Remembered, edited by Audrey Coppard and Bernard Crick (1984). There, one is struck first by Orwell’s total absence of practical competence, or of simple common sense—and secondly by his calm courage and absolute self-control, which prevented the little party from panicking. And yet, at the time, he had entertained no illusions regarding their chances of survival; as he simply told his nephew afterward: “I thought we were goners.” And the nephew commented: “He almost seemed to enjoy it.”

Conclusion: if one had to go out to sea in a small boat, one would not choose Orwell to skipper. But when meeting with shipwreck, disaster, or other catastrophes, one could not dream of better company.

Orwell left explicit instructions that no biography be written of him, and he even actively discouraged one early attempt. He felt that “every life viewed from the inside would be a series of defeats too humiliating and disgraceful to contemplate.” And yet the posthumous treatment he received from his biographers and editors is truly admirable—I think in particular of the works of Bernard Crick and of Peter Davison, whose volumes are models of critical intelligence and scholarship.

In Davison’s selection of the correspondence, Orwell, unlike many other letter writers, is always himself and speaks with only one voice: reserved even with old friends; generous with complete strangers; and treating all with equal sincerity. As the director of the BBC Indian services, for which Orwell broadcast during World War II, wrote, “He is transparently honest, incapable of subterfuge and, in early days, would have either been canonized—or burnt at the stake! Either fate he would have sustained with stoical courage.”

The letters illustrate all his main concerns, interests, and passions; they also illuminate some striking aspects of his personality.

Politics

Orwell once defined himself half in jest—but only half—as a “Tory Anarchist.” Indeed, after his first youthful experience in the colonial police in Burma, he only knew that he hated imperialism and all forms of political oppression; all authority appeared suspect to him, even “mere success seemed to me a form of bullying.” Then after his inquiry into workers’ conditions in northern industrial England during the Depression he developed a broad nonpartisan commitment to “socialism”: “socialism does mean justice and liberty when the nonsense is stripped off it.” The decisive turning point in his political evolution took place in Spain, where he volunteered to fight fascism. First he was nearly killed by a fascist bullet and then narrowly escaped being murdered by the Stalinist secret police:

What I saw in Spain, and what I have seen since of the inner workings of left-wing political parties, have given me a horror of politics…. I am definitely “left,” but I believe that a writer can only remain honest if he keeps free of party labels. [My emphasis.]

From then on he considered that the first duty of a socialist is to fight totalitarianism, which means in practice “to denounce the Soviet myth, for there is not much difference between Fascism and Stalinism.” Inasmuch as they deal with politics, the Letters focus on the antitotalitarian fight. In this, the three salient features of Orwell’s attitude are his intuitive grasp of concrete realities, his nondoctrinaire approach to politics (accompanied with a deep distrust of left-wing intellectuals), and his sense of the absolute primacy of the human dimension. He once identified the source of his strength:

Where I feel that people like us understand the situation better than so-called experts is not in any power to foretell specific events, but in the power to grasp what kind of world we are living in.

This uncanny ability received its most eloquent confirmation when Soviet dissidents who wished to translate Animal Farm into Russian (for clandestine distribution behind the Iron Curtain) wrote to him to ask for his authorization: they wrote to him in Russian, assuming that a writer who had such a subtle and thorough understanding of the Soviet reality—in contrast with the dismal ignorance of most Western intellectuals—naturally had to be fluent in Russian!

Orwell’s revulsion toward all “the smelly little orthodoxies that compete for our souls” also explains his distrust and contempt of intellectuals: this attitude dates back a long way, as he recalls in a letter of October 1938:

What sickens me about left-wing people, especially the intellectuals, is their utter ignorance of the way things actually happen. I was always struck by this when I was in Burma and used to read anti- imperialist stuff.

If the colonial experience had taught Orwell to hate imperialism, it also made him respect (like the protagonist in a Kipling story) “men who do things.”

In the end, Orwell seems to have essentially reverted to his original position of “Tory Anarchist.” In a letter to Malcolm Muggeridge, there is a statement that seems to me of fundamental importance: “The real division is not between conservatives and revolutionaries but between authoritarians and libertarians.”

The Human Factor

Even in the heat of battle, and precisely because he distrusted ideology—ideology kills—Orwell remained always acutely aware of the primacy that must be given to human individuals over all “the smelly little orthodoxies.” His exchange of letters (and subsequent friendship) with Stephen Spender provides a splendid example of this. Orwell had lampooned Spender (“parlour Bolshevik,” “pansy poet”); then they met: the encounter was actually pleasant, which puzzled Spender, who wrote to Orwell on this very subject. Orwell, who later became a friend of Spender’s, replied:

You ask how it is that I attacked you not having met you, & on the other hand changed my mind after meeting you…. [Formerly] I was willing to use you as a symbol of the parlour Bolshie because a. your verse…did not mean very much to me, b. I looked upon you as a sort of fashionable successful person, also a Communist or Communist sympathiser, & I have been very hostile to the C.P. since about 1935, and c. because not having met you I could regard you as a type & also an abstraction. Even if, when I met you, I had happened not to like you, I should still have been bound to change my attitude, because when you meet someone in the flesh you realise immediately that he is a human being and not a sort of caricature embodying certain ideas. It is partly for this reason that I don’t mix much in literary circles, because I know from experience that once I have met & spoken with anyone I shall never again be able to show any intellectual brutality towards him, even when I feel that I ought to, like the Labour M.P.s who get patted on the back by dukes & are lost forever more.

Which immediately calls back to mind a remarkable passage of Homage to Catalonia: Orwell described how, fighting on the front line during the Spanish civil war, he saw a man jumping out of the enemy trench, half-dressed and holding his trousers with both hands as he ran:

I did not shoot partly because of that detail about the trousers. I had come here to shoot at “Fascists”; but a man who is holding up his trousers isn’t a “Fascist,” he is visibly a fellow creature, similar to yourself, and you don’t feel like shooting at him.

Literature

From the very start, literature was always Orwell’s first concern. This is constantly reflected in his correspondence: since early childhood “I always knew I wanted to write.” This statement is repeated in various forms, all through the years, till the end. But it took him a long time (and incredibly hard work) to discover what to write and how to write it. (His first literary attempt was a long poem, eventually discarded.) Writing novels became his dominant passion—and an accursed ordeal: “writing a novel is agony.” He finally concluded (some would say accurately), “I am not a real novelist.” And yet shortly before he died he was still excitedly announcing to his friend and publisher Fredric Warburg, “I have a stunning idea for a very short novel.”

As the Letters reveal, he reached a very clear-sighted assessment of his own work. Among his four “conventional” novels, he retained a certain fondness for Burmese Days, which he found faithful to his memories of the place. He felt “ashamed” of Keep the Aspidistra Flying and, even worse, of A Clergyman’s Daughter and would not allow them to be reprinted: “They were written…for money…. At that time I simply hadn’t a book in me, but I was half starved.” He was rightly pleased with Coming Up for Air, written at one go, with relative ease; and it is indeed a most remarkable book—about an insurance salesman who finds that the places he knew as a boy have been ruined—and it is quite prescient, in the light of today’s environmental concerns. Among the books worth reprinting he listed (in 1946—Nineteen Eighty-Four was not written yet) first of all, and by order of importance: Homage to Catalonia; Animal Farm; Critical Essays; Down and Out in Paris and London; Burmese Days; Coming Up for Air.

The Common Man

The extraordinary lengths to which Orwell would go in his vain attempts to turn himself into an ordinary man are well illustrated by the Wallington grocery episode, on which the Letters provides colorful information. In April 1936, Orwell started to rent and run a small village grocery, located in an old, dark, and pokey cottage—insalubrious and devoid of all basic amenities (no inside toilet, no cooking facilities, no electricity—only oil lamps for lighting). On rainy days the kitchen floor was underwater; blocked drains turned the whole place into a smelly cesspool. Davison comments: “One may say without being facetious, it suited Orwell to the ground.” And it especially suited Eileen, his wonderfully Orwellian wife. She moved in the day of their marriage, in 1936, and the way she managed this improbable home testifies both for her heroism and for her eccentric sense of humor. The income from the shop hardly ever covered the rent of the cottage. The main customers were a small bunch of local children who used to buy a few pennies’ worth of lollipops after school. By the end of the year, the grocery went out of business, but at that time it had already fulfilled its true purpose: Orwell was in Barcelona, volunteering to fight against fascism, and when he enlisted into the Anarchist militia, he could proudly sign “Eric Blair, grocer.”

Fairness

Orwell’s sense of fairness was so scrupulous, it extended even to Stalin. As Animal Farmwas going into print, at the last minute, Orwell sent a final correction—which was effected just in time. (As all readers will remember, “Napoleon” is the name of the leading pig, which, in Orwell’s fable, represented Stalin.)

In chapter VIII…when the windmill is blown up, I wrote “all the animals including Napoleon flung themselves on their faces.” I would like to alter it to “all the animals except Napoleon.” …I just thought the alteration would be fair to [Stalin] as he did stay in Moscow during the German advance.

Poverty and Ill-Health

Orwell was utterly stoic and never complained about his material and physical circumstances, however distressing they were most of the time. But from the information provided by the Letters, one realizes that his material insecurity (which, at times, reached extreme poverty) ceased only three years before his death, when he received his first royalties windfall from Animal Farm; while his health became a severe and constant problem (undiagnosed tuberculosis) virtually since his return from Burma, at age twenty-five. In later years he required frequent, prolonged, and often painful treatment in various hospitals. For the last twelve years of his short existence (he died, age forty-six, in 1950) he was in fact an invalid—yet insisted most of the time on carrying on with normal activity.

His entire writing career lasted for only sixteen years. The quantity and quality of work produced during this relatively brief span of time would be remarkable even for a healthy man of leisure; that it was achieved in his appalling state of permanent ill-health and poverty is simply stupendous.

Women

In his relations with women, Orwell seems to have been generally awkward and clumsy. He was easily attracted by them, whereas they seldom found him attractive. Still, by miraculous luck, he found in Eileen O’Shaughnessy a wife who was able not only to understand him in depth, but also to love him truly and bear with his eccentricities, without giving up any of her own originality—an originality that still shines through all her letters. If Orwell was a failed poet, Eileen for her part was pure poetry.

Her premature death in 1945 left Orwell stunned and lost for a long time. A year later he abruptly approached a talented young woman he hardly knew (they lived in the same building); with a self-pity that was utterly and painfully out of character for such a proud man, he wrote to her telling her how sick he was and offering her “to be the widow of a literary man.”

I fully realise that I’m not suited to someone like you who is young and pretty…. It is only that I feel so desperately alone…. I have…no woman who takes an interest in me and can encourage me…. Of course it’s absurd a person like me wanting to make love to someone of your age. I do want to, but…I wouldn’t be offended or even hurt if you simply say no…

The woman was flabbergasted and politely discouraged him.

Some years earlier he also made an unfortunate and unwelcome pass at another woman; this episode is documented by the editor with embarrassing precision—at which point readers might remember Orwell’s hostility toward the very concept of biography. Do biographers, however serious and scrupulous, really need or have the right to explore and disclose such intimate details? Yet we still read them. Is it right for us to do so? I honestly do not know the answer.

Solid Objects and Scraps of Useless Information—Trees, Fishes,Butterflies, and Toads

In his essay “Why I Write,” Orwell said:

I do not want completely to abandon the world-view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue…to love the surface of the earth, and to take pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information.

And in his famous “Some Thoughts on the Common Toad,” he added:

If a man cannot enjoy the return of spring, why should he be happy in a labour-saving Utopia?… I think that by retaining one’s childhood love of such things as trees, fishes, butterflies and…toads, one makes a peaceful and decent future a little more probable.

His endearing and quirky tastes, his inexhaustible and loving attention to all aspects of the natural world, crop up constantly in his correspondence. The Letters are full of disarming non sequiturs: for instance, he interrupts some reflections on the Spanish Inquisition to note the daily visit that a hedgehog pays to his bathroom. While away from home in 1939, he writes to the friend who looks after his cottage: his apprehensions regarding the looming war give way without transition to concerns for the growth of his vegetables and for the mating of his goat:

I hope Muriel’s mating went through. It is a most unedifying spectacle, by the way, if you happened to watch it…. Did my rhubarb come up, I wonder? I had a lot, & then last year the frost buggered it up.

To an anarchist friend (who became a professor of English in a Canadian university) he writes an entire page from his Scottish retreat, describing in minute detail all aspects of the life and work of local crofters: again the constant and inexhaustible interest for “men who do things” in the real world.

The End

While already lying in hospital, he married Sonia Brownell three months before his death. At that time he entertained the illusion that he might still have a couple of years to live and he was planning for the following year a book of essays that would have included a long essay on Joseph Conrad (if it was ever written, it is now lost). He also said that he still had two books on his mind—besides the “stunning idea for a very short novel” mentioned earlier.

He began drawing plans to have a pig, or preferably a sow, in his Scottish hermitage of the Hebrides. As he instructed his sister who was in charge of the place:

The only difficulty is about getting her to a hog once a year. I suppose one could buy a gravid sow in the Autumn to litter about March, but one would have to make very sure that she really was in pig the first time.

In his hospital room, at the time of his death, he kept in front of him, against the wall, a good new fishing rod, a luxury he had indulged himself with on receiving the first royalties from Nineteen Eighty-Four. He never had the chance to use it.

His first love—dating back to his adolescence and youth—who was now a middle-aged woman, wrote to him in hospital out of the blue, after an estrangement and silence of some twenty-seven years. He was surprised and overjoyed, and resumed correspondence with her. In his last letter to her, he concluded that, though he could only entertain a vague belief in some sort of afterlife, he had one certainty: “Nothing ever dies.”

***

Source:

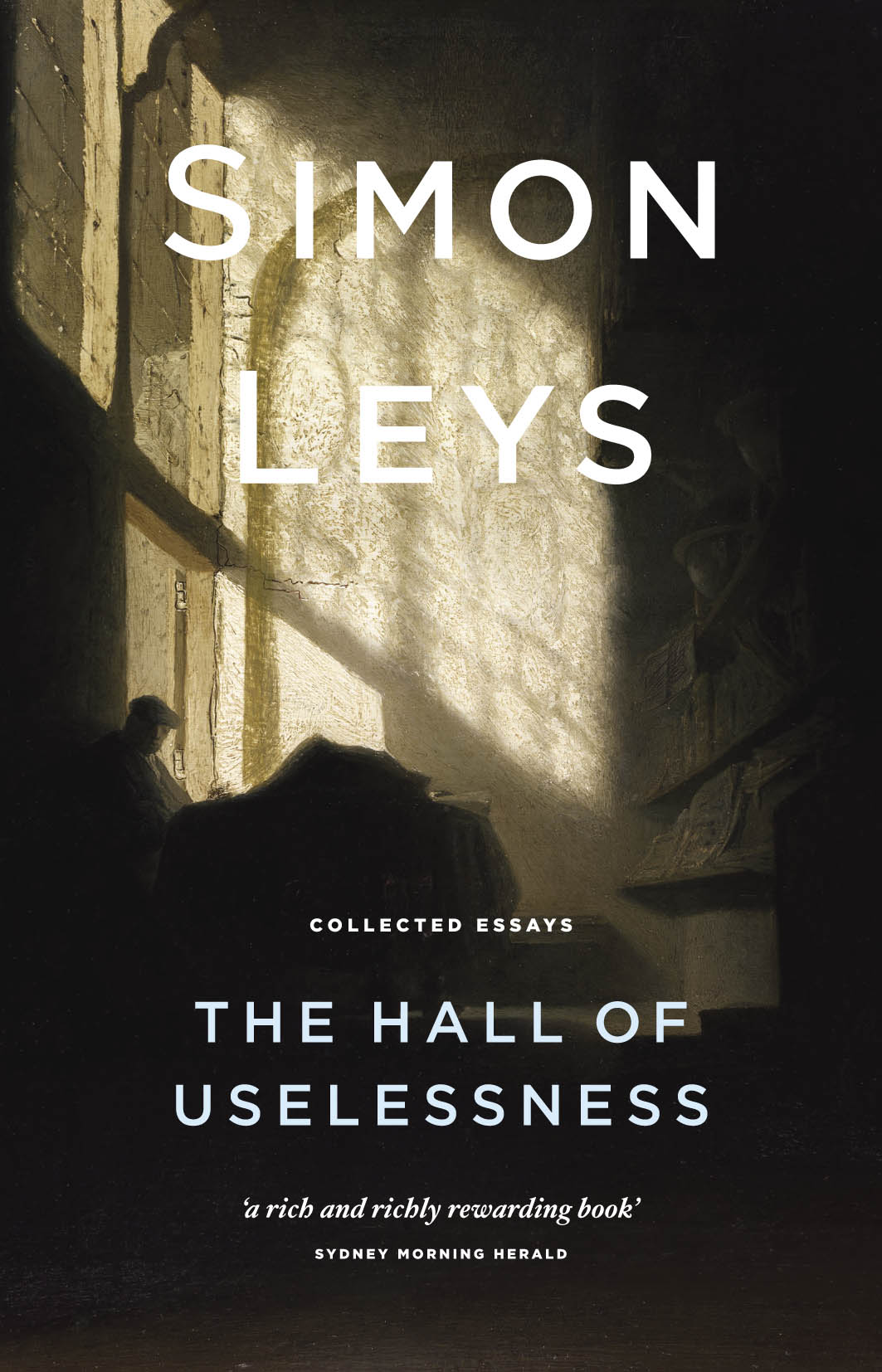

- Simon Leys, The Intimate Orwell, New York Review of Books, 26 May 2011; reprinted in The Hall of Uselessness: Collected Essays, 2012

A Happy Vicar I Might Have Been

George Orwell

A happy vicar I might have been

Two hundred years ago

To preach upon eternal doom

And watch my walnuts grow;But born, alas, in an evil time,

I missed that pleasant haven,

For the hair has grown on my upper lip

And the clergy are all clean-shaven.And later still the times were good,

We were so easy to please,

We rocked our troubled thoughts to sleep

On the bosoms of the trees.All ignorant we dared to own

The joys we now dissemble;

The greenfinch on the apple bough

Could make my enemies tremble.But girl’s bellies and apricots,

Roach in a shaded stream,

Horses, ducks in flight at dawn,

All these are a dream.It is forbidden to dream again;

We maim our joys or hide them:

Horses are made of chromium steel

And little fat men shall ride them.I am the worm who never turned,

The eunuch without a harem;

Between the priest and the commissar

I walk like Eugene Aram;And the commissar is telling my fortune

While the radio plays,

But the priest has promised an Austin Seven,

For Duggie always pays.I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls,

And woke to find it true;

I wasn’t born for an age like this;

Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?

Submitted to Adelphi magazine in 1935, this poem later appeared in Why I Write, 1946