Watching China Watching (X)

‘To be right too soon is the worst way of being wrong.’

— Simon Leys

Peking Duck Soup is a unique document in the annals of China-Watching. Made by a group of China specialists — Francis Deron, Jean-Paul Tchang and René Viénet — this 1977 film is also known under the title Chinois, encore un effort pour être révolutionnaires (Once again, people of China, if you really want to be revolutionaries!).

The film shares much in common with the observations, and temper, of Simon Leys (Pierre Ryckmans). In fact, some years earlier René Viénet, one of the film’s directors, introduced a few draft chapters of Leys’ Les habits neufs du président Mao: chronique de la Révolution culturelle (The Chairman’s New Clothes) to the publisher Editions Champs libre in Paris. As Leys later wrote of this controversial book, which appeared in 1971 at a time when the miasma of China’s Cultural Revolution still beclouded the French intelligentsia:

What other publisher could have envisaged a publication like that at that particular moment? The Chairman’s New Clothes denounced Mao from a left-wing point of view, exposing his regressive-feudal character: that view was obviously unacceptable to the orthodox French left, and incomprehensible on the right.

As for Viénet, Ryckmans remarked that he ‘stood out sharply from the sad, drab nest of vipers of French sinology’ (le triste et grisâtre panier de crabes de la sinologie française), and that:

One thing is certain: without him I would probably never have published anything — you could say fairly that it was Viénet who invented me. Une chose est certaine: sans lui je n’aurais probablement jamais rien publié – on pourrait dire assez littéralement que c’est Viénet qui m’a inventé.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

23 January 2018

***

Related Material:

- Watching China Watching, China Heritage, 5 January 2018-

- The China Expert and The Ten Commandments — Watching China Watching (I), China Heritage, 5 January 2018

- Non-existent Inscriptions, Invisible Ink, Blank Pages — Watching China Watching (II), China Heritage, 7 January 2018

- René Goldman, ‘Second Thoughts on Democracy and Dictatorship in China Today’, Pacific Affairs, vol.51, no.3 (Autumn, 1978): 460-481

- Paul Hollander, Political Pilgrims: Travels of Western Intellectuals to the Soviet Union, China, and Cuba 1928-1979, New York: Oxford University Press, 1981

- The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1999

- Laurent Six, Aux origines d’Ombres chinoises: une mission de six mois au service de l’ambassade de Belgique en République populaire de Chine, Textyles, no.34 (2008): 65-77

- Philippe Paquet, Simon Leys: Navigator Between Worlds, trans. Julie Rose, Melbourne: La Trobe University Press in conjunction with Black Inc., 2017, pp.230-234

***

Progress in the New Epoch

Two and two makes six, says the tyrant. Two and two make five, says the moderate tyrant. To the heroic individual who would recall, at his peril, that two and two make four, the police say: ‘All the same, you don’t want to go back to the days when two and two make six!’ So goes the crazy pressure of the lie.

Deux et deux font six, dit le tyran. Deux et deux font cinq, dit le tyran modéré. A l’individu héroïque qui rappellerait, à ses risques et périls, que deux et deux font quatre, des policiers disent : « Vous ne voudriez tout de même pas qu’on revienne à l’époque où deux et deux faisaient six ! » Ainsi va la pression hallucinée du mensonge.

— Philippe Sollers, Deux et deux font quatre,

quoted in Philippe Paquet, Simon Leys:

Navigator Between Worlds, 2017, p.373

Peking Duck Soup

a film by Francis Deron, Jean-Paul Tchang and René Viénet

Excerpt #1

Excerpt #2

Excerpt #3

Full Version

Peking Duck Soup

a review by Simon Leys

‘Comrades, you should always bear your own responsibilities. If you’ve got to shit, shit! If you’ve got to fart, fart! Don’t hold things down in your bowels, and you’ll feel easier.’ 同志們,自己的責任都要分析一下,有屎拉出來,有屁放出來,肚子就舒服了。(在廬山會議上的講話)

Thus the Great Helmsman (the red sun, brightest red, who shone in every heart — the very same man whom M. Giscard d’Estaing in one of his more playful moods affectionately dubbed ‘the beacon of human thinking’).

The makers of the film Peking Duck Soup have had the bad taste to follow the bold advice of the Great Teacher. It’s a good bet that the Maoists (if there are any left after Chairman Hua’s clean sweep), of whatever cloth or congregation, will not be very grateful for the film, since it is one of their religion’s basic precepts to show their respect for their God by never reading His writings (except in the digest cooked up by Mao’s Closet-Comrade-in-Arms) and above all to draw a modest veil over the real adventures in His career. After all, not even the most precocious little boy would have the heart to ask Father Christmas for his identity papers.

The makers of Peking Duck Soup have undertaken an indecent and scandalous task: they have traced the history of a régime which has made it its special business to proscribe history and condemn historians to suicide. The material it uses (painstakingly assembled and edited over a number of years by a group of researchers and Sinologists) is dreadfully subversive, and will assuredly elicit protests from the Peking authorities and their official and unofficial representatives in France, as well as the general disapprobation of all people of good taste. Actually, more than ninety-five per cent of their film consists of documents, photographs, newsreels originally produced and released by Peking’s own official bodies — the propaganda department, the film services of the People’s Liberation Army, etc. etc. You have to bear in mind that in Maoist China it is an unorthodox and subversive undertaking to explore even the most recent past. Do you suppose that Hua Guofeng like being reminded today about how only yesterday he was goading on the nation to pillory Deng Xiaoping? (And what about Joris Ivens, the film-goer’s best-known source of ‘information’ about China: when he is busy denouncing Madam Mao, do you think he gets any fun out of having his nose rubbed in those images which show him to have been the Empress’s ecstatic courtier in her days of splendour?) And what poor taste, to remind us that the ‘Gang of Four’ was actually the ‘Gang of Five’ (without Mao it would ever have existed), and how Lin Biao became the Great Leader’s Closest-Comrade-in-Arms, then his chosen successor, etc. etc.

‘In Maoist China it is the past which is unpredictable’, as Jean Pasqualini has remarked. [Author’s Note: Bao Ruo-wang 鮑若望 (Jean Pasqualini), Prisoner of Mao, London, 1975]. At any moment, whole slabs of history can collapse with the sudden fall of the latest batch of disgraced leaders, victims of the power struggle which rages permanently in the upper reaches of the hierarchy. These instantaneously unmentionable relics are at once spirited away behind the great word-battlements of a crack-brained ideology which is expert at ‘waving the red flag to fight the red flag’, at ‘splitting one into two and two into one’, and metamorphosing ‘left’ into ‘right’ and ‘right’ into ‘left’, not to mention the ‘crypto-left far right’ or the ‘crypto-right far left’. With a vast and dreadful zest and a cruelly accurate memory, the Peking Duck Soup team has tried to exhume a past condemned to oblivion by Peking, to unearth and strip down the machinery of the system which Li Yizhe — our most reliable guide to understanding present-day China — described with great precision as a ‘socialist-fascist régime of a feudal type’. [Author’s Note: In their famous manifesto On Socialist Democracy and Legality 關於社會主義民主與法制. Li Yi-che 李一哲 is the collective pen-name of Li Zhengtian 李正天, Chen Yiyang 陳一陽 and Wang Xizhe 王希哲.]

‘With you in charge, I feel comfortable,’ 你辦事, 我放心 Mao used to tell Hua Guofeng. ‘With them in charge, the people feel uncomfortable,’ the makers of this film retort, and with good reason. The psychology and behaviour of Peking’s ruling clique are those of gangsters. This in not just a colourful and polemical way of speaking but a sober statement of fact, and in fact it is the underworld which might find the comparison insulting — after all its members do have some sense of honour (even of a perverse variety), personal loyalty, and a warped kind of brotherhood in arms. That is a lot more than can be said for the turncoats and cut-throats of the Forbidden City, whose ceaseless intrigues and mutual waylaying round the corners of the corridors of power, as well as their cynically shifting alliances, are proof of a lack of principle which would have brought a blush to the cheeks of the members of the secret societies of the old Shanghai underworld.

This comparison with criminal morals and practice — underlined in the film by pertinent (but repeated to the point of tedium) cuts to images of kung-fu and karate fighting — will doubtless come as a shock to people used to plugging their ears with the daily cotton wool of Le Monde, as it will to those who attend the colloquiums organised by certain reverend fathers on the theology implications of Mao Zedong Thought, but it will certainly come as no surprise to readers of the People’s Daily, who have long since become familiar with descriptions of the plots and treason hatched by the Closest-Comrade-in-Arms and then by the Widow and her Henchmen.

Smooth tongues have virtues unknown to virtue: the linguistic propriety, which during the joint pontificate of these two was observed by soft-soaping journalists and trendy ecclesiastics, largely succeeded in censoring public awareness of the raw and bloody evidence for the great free-for-all in which the Maoist Mandarins scrambled to settle their scores with dagger, machine-gun, bomb, poisoned vial or what have you. But the commentary to Peking Duck Soup restores to this bloodthirsty carnival its original vigour, which for too long has been suppressed by upright and decent-minded conformists.

It is a measure of the intoxication and distortion of judgement suffered by quite a number of the French public that a film like this, based on impressive historical research by a team of specialists in Chinese Studies, should already have been dismissed by some people as if it were some sort of colourful hoax, whereas any old line of Mao-sympathising falsification can pass off at once without debate. The public’s ignorance makes the most brazen lies possible, and this ignorance is maintained by the phenomenon of the ‘new censorship’ so well analysed by Jean-François Revel in his latest book. [Author’s Note: The Totalitarian Temptation, London, 1977.] Even in the necessarily apolitical town of Hong Kong, Pic’s film about modern China started a genuine riot when shown on TV: what Pic had done was to use the appalling footage — sacred to all Chinese, whatever their political alignment — of the ‘Rape of Nanking’, the most notorious of the Japanese atrocities carried out in China, as an ‘example of the crimes of the Kuomintang’! This idiotic sacrilege, which no critic picked up here, did no harm at all to the film’s career in the West: lie resoundingly enough and you will be taken for a respectable historian, but as the compilers of Révo. cul. dans la Chine pop. have already learned and the makers of Peking Duck Soup are beginning to find out, you may collect a mass of precious and unimpeachable evidence but if you season your compilation with three or four barbed references offending the opinion-makers, no matter what the calibre of your work, you will see it reduced to the proportions of a ‘lavatory attendant’s joke’. [Author’s Note: This is how André Fontaine actually described Révo. cul. dans la Chine pop. in Le Monde, 12 February 1975.]

‘The action takes place in the second half of the twentieth century’, one subtitle sardonically remarks, as the film is about to plunge us back into the hysterical liturgies and medieval thaumaturgies of the Mao cult with all its greatest extravagances. Yet these images of delirium and debased intelligence — which once again are those provided by the official propaganda of the day — unbearable though they are, are never used here in such a way as to insult the Chinese people: it is the leaders who insult them, not the film-makers. On the contrary, the film establishes a masterly counterpoint between the lugubrious scenes of mandarin Grand Guignol and the great human tide surging in the foreground. Animated by epic rhythms reminiscent of Eisenstein, the camera lingers on the vast and continually renewed variety of the crowd, and becomes intoxicated with faces — faces of waiting, of hope, of anger, dumb but so eloquent faces, the faces of a whole people, who sooner or later will have the last word. The strident, mythical, unreal world of the leaders is continually contrasted with the real historical world of the masses. A striking sequence cutting between old newsreels on the people’s sorrows and struggles and the stereotyped images of the same themes as rendered by the ‘model revolutionary operas’ of Madame Mao shows how the tragedy of the Chinese revolution has been systematically blurred and turned into slushy pap by Maoist propaganda.

The focus of the film’s commentary is the basic text of Li Yizhe, ‘On Socialist Democracy and Legality’; speech is restored to the Chinese people, and we see them sitting in judgement on their masters. This is obviously intolerable for the faithful: in the two cinemas where the film has been shown, it is no coincidence that the kommandos of ‘social fascism of a feudal character’ have chosen to make their disturbances at the precise (and for them unendurable) point where we see popular anger culminating in the mass demonstrations of 5 April 1976. The fact that on this date a hundred thousand Chinese spontaneously attempted to bury the Great Helmsman before he had breathed his last — that was what our right-thinking people could not swallow, for they had already decided (in concert with the Shah of Iran, Felix Greene, Han Suyin and Shirley MacLaine) that they know what was best for the Chinese — Maoism – without actually consulting them.

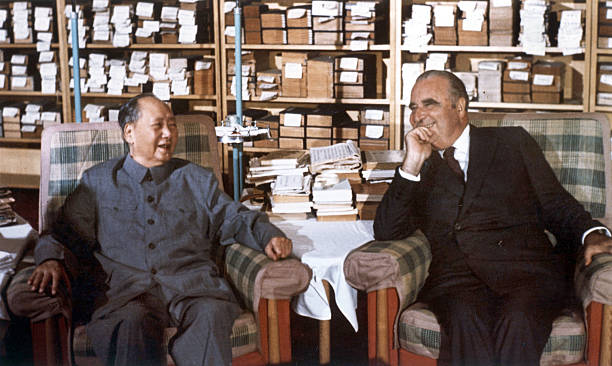

Images from the Mao-Pompidou meeting: while the screen shows us the two leaders putting their great jovial heads together for a talk, the soundtrack plays the tune of Jingle Bells barked by a clever collection of singing dogs. This vocal rendition by trained poodles, so mercifully drowning out the words of the two statesmen — if your remember, their actual exchange, conducted with the sententious wisdom of a pair of travelling salesmen in ladies’ underwear, concerned the historical evidence (and some conjecturers) on Napoleon’s stomach troubles — barely has time to ruffle the delicate good taste of all sensitive members of the audience when the real act of indecency occurs. A subtitle reminds us of the unforgivable (and carefully buried) obscenity which was perpetrated at the time of the French Foreign Ministry’s Chinese initiative, and was approved by Pompidou at the instance of his ambassador in Peking in order not to cast any cloud over the encounter between these two ancient wrecks. Do you remember (did you ever hear it mentioned?) the case of the young Chinese man who had been promised political asylum in France, only for that country to break its word and deliver him, still half-comatose, to his Maoist jailers, who dragged him from his hospital bed and flew him to Peking, to an obvious fate, with the blessing of the supreme French authorities — these tinpot Machiavellis who thought they were cultivating high diplomacy when they were simply using gutter police methods?

The film thus unites implacable precision with a triumphant bad taste, raised to the level of a critical method, that digs up everything decent people have agreed to forget. It takes a lot of courage, or lack of consciousness, to defy fashion, decency and the powers-that-be so systematically. How will the public react to this mad undertaking? One would like to hope that the recent change of direction by the French intelligentsia would work in favour of the healthy breakthrough which the film makes; nevertheless one feels anxious. To be right too soon is the worst way of being wrong: the customers of the nouveaux philosophes are likely to find it difficult to forgive the makers of Peking Duck Soup, for not falling for any of the aberrations where were after all the conversational fuel for several Paris seasons. And these philosophers, who in the quaint Seine-side dialect are known as ‘new’ (presumably because it took them only forty years to spot something which, as they say in Peking, was as ‘plain as a louse on a monk’s skull’ [和尚頭上的蝨子——明摆着。— Ed.]), appear to me to be distinguished mainly for their shrewd sense of opportunity: when it comes to sniffing which way the wind blows or forecasting changes in the weather, their sensitivity could compete with the legendary meteorological prescience of rheumatism among light-house keepers. Where Maoism is concerned, in fact, they seem to have displayed a circumspection worthier of a horse trader at a cattle fair, but the fact that it has now earned them such popularity in the ideas market augurs badly for the immediate future of Peking Duck Soup, should the film’s success have to depend on this same public.

So how should I finally sum up the liberating vigour which radiates from this film, black and ferocious though it is?

‘It is a great shame to see the proletarian masses led blindfold by rubicund priests who do not even condescend to tell them where they are going,’ said André Breton. [Author’s Note: Quoted by Claude Roy, Somme toute, Paris, 1976, p.276] It is a great delight to see these twisted manoeuvrings finally exposed to the general view in such a ruthless light.

Source:

An abridged version of ‘Peking Duck Soup’ appeared in L’Express, 14 November 1977. The full version, translated by Steve Cox, is collected in Simon Leys, Broken Images: Essays on Chinese Culture and Politics, New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1979, pp.67-73.

Chinese names have been converted to Hanyu pinyin and characters have been added where deemed appropriate.

— Ed.