Spectres & Souls

The 12th of February 2021 marks the end of an eventful Gengzi Year of the Rat 庚子鼠年 and the first day of the Xinchou Year of the Ox 辛丑牛年 of 2021-2022. The title of China Heritage Annual 2021 is Spectres & Souls and one of the themes of the Annual will be a contestation between China (which has often figured itself as the epicenter of ‘The East’) and the United States of America. Both countries make claims that their history, society and politics somehow make them ‘exceptional’.

Since the nineteenth century, a common stereotype related to China, and ‘The East’ (a vague region stretching from the Indian subcontinent to the Japanese archipelago) more generally, is that ‘Eastern civilisation’ is somehow more attuned to nature and the spiritual in contrast to the grasping and materialist West.

We mark the start of the Xinchou Lunar Year of 2020-2021 with a modest chapter in Spectres & Souls that is devoted to one of the most popular representations of the ‘spiritual east’: the Ten Ox-herding Pictures. These images, which have been known for over a millennium in various guises, are accompanied by famous verses (gathā 偈) translated by D.T. Suzuki, one of the most famous post-WWII interpreters of ‘Eastern wisdom’ in the West. Here we have added the original Chinese text of those verses below Suzuki’s rendition.

D.T. Suzuki (Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō, 鈴木大拙貞太郎, 1870-1966) was acclaimed internationally for the long decades he devoted to popularising Buddhist philosophy and Zen practice through his writings, translations and lectures. Suzuki’s work still offers accessible accounts of Buddhist thought, even as his reputation has been tarnished by controversies surrounding his supposed sympathies for Japanese militarism and imperialism (see, for example, the work of Brian Victoria).

According to D.T. Suzuki, the Ming-dynasty monk Zhuhong of Yunqi Monastery (Yunqi Zhuhong 雲栖祩宏, 1535-1615) is associated with the verses that for centuries have accompanied the Ten Ox-herd Pictures featured below. Although a student of Chan/ Zen enlightenment and a key figure in the late-Ming Buddhist revival, Zhuhong also famously displayed a certain spiritual narrowness, something reflected in his offhand rejection of the Christian beliefs of the newly arrived Jesuit missionaries. His treatise ‘Explanation of Heaven’ 天說 Tiān shuō, published in 1615, gloomily echoed the dyspeptic temper of the Tang-dynasty Confucian Han Yu 韓愈 who, some seven hundred years earlier, had decried Buddhism and all of its practices. Both men warned against the alien creeds they feared would undermine the unique spiritual essence of their homeland, and their own authority.

***

I first encountered D.T. Suzuki’s account of the Ox-herd Pictures as a teenager in a reprint of his 1935 Manual of Zen Buddhism, a copy of which I acquired at the Adyar Bookshop of the Theosophical Society in Sydney (long since relocated). It was the mid 1960s, and my interest in Zen and Tibetan Buddhism grew in tandem with my fascination in Maoism and the Cultural Revolution, a topic which I have discussed elsewhere. (See: ‘Mangling May Fourth 2020 in Washington’, China Heritage, 14 May 2020.)

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

12 February 2021

First Day of the First Month of the

Xinchou Year of the Ox

辛丑牛年正月初一

***

Further Reading:

- China Heritage Annual 2021: Spectres & Souls

- China Heritage Annual 2020: Viral Alarm

- ‘Ten Verses on Oxherding’, 1278, Kamakura period, Japan, The MET

The Ten Oxherding Pictures

十牛圖

Shí niú tú / Jūgyūzu

普明

Puming / Fumyō

translated by D. T. Suzuki

鈴木大拙貞太郎

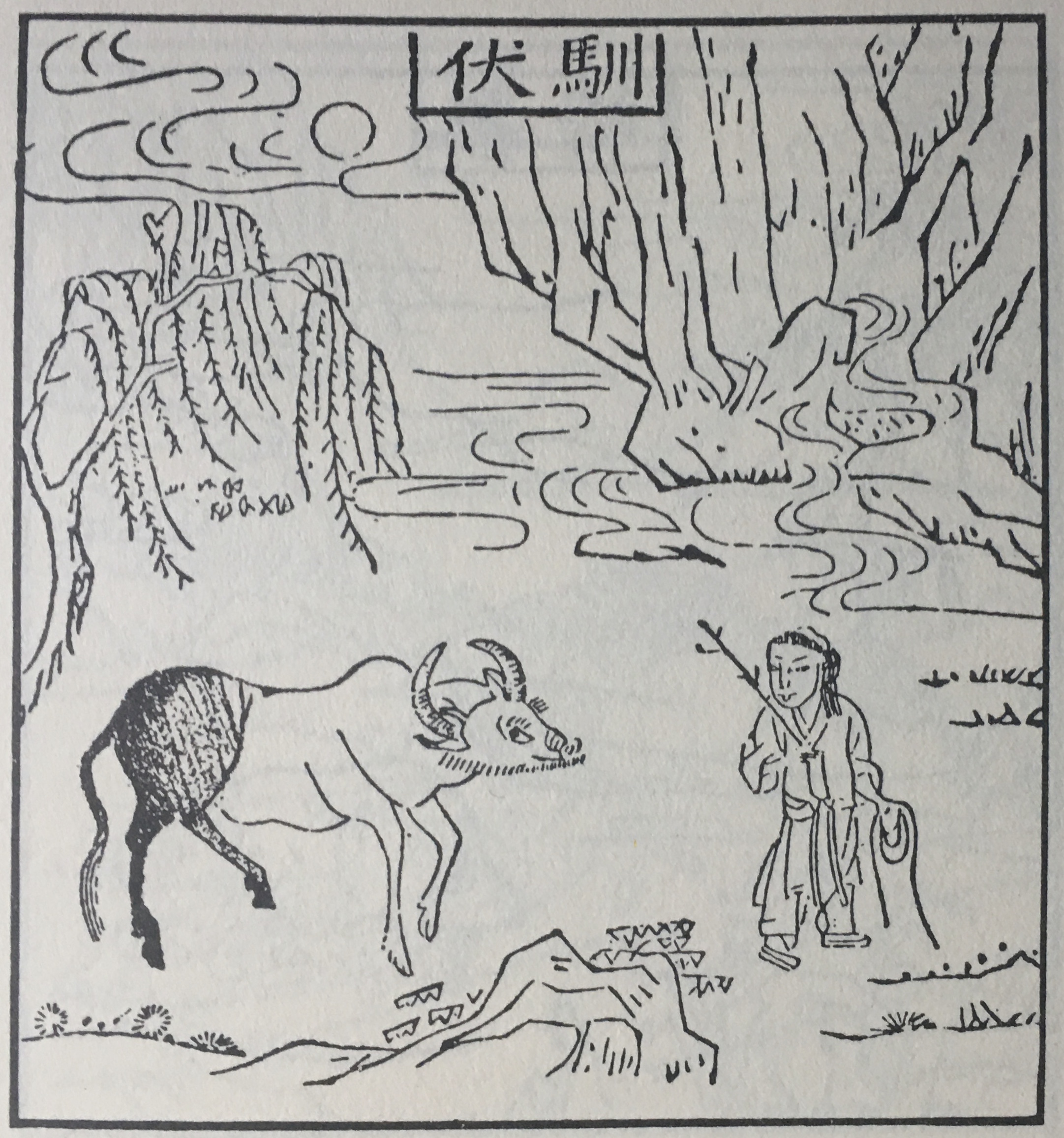

One: Undisciplined

With his horns fiercely projected in the air the beast snorts,

Madly running over the mountain paths, farther and farther he goes astray!

A dark cloud is spread across the entrance of the valley,

And who knows how much of the fine fresh herb is trampled under his wild hoofs!

未牧第一

猙獰頭角恣咆哮,奔走溪山路轉遙;

一片黑雲橫谷口,誰知步步犯佳苗。

***

Two: Discipline Begun

I am in possession of a straw rope, and I pass it through his nose,

For once he makes a frantic attempt to run away, but he is severely whipped and whipped;

The beast resists the training with all the power there is in a nature wild and ungoverned,

But the rustic oxherd never relaxes his pulling tether and ever-ready whip.

初調第二

我有芒繩驀鼻穿,一回奔競痛加鞭;

從來劣性難調製,猶得山童盡力牽。

***

Three: In Harness

Gradually getting into harness the beast is now content to be led by the nose,

Crossing the stream, walking along the mountain path, he follows every step of the leader;

The leader holds the rope tightly in his hand never letting it go,

All day long he is on the alert almost unconscious of what fatigue is.

受制第三

漸調漸伏息奔馳,渡水穿雲步步隨;

手把芒繩無少緩,牧童終日自忘疲。

***

Four: Faced Round

After long days of training the result begins to tell and the beast is faced round,

A nature so wild and ungoverned is finally broken, he has become gentler;

But the tender has not yet given him his full confidence,

He still keeps his straw rope with which the ox is now tied to a tree.

回首第四

日久功深始轉頭,顛狂心力漸調柔;

山童未肯全相許,猶把芒繩且系留。

***

Five: Tamed

Under the green willow tree and by the ancient mountain stream,

The ox is set at liberty to pursue his own pleasures;

At the eventide when a grey mist descends on the pasture,

The boy wends his homeward way with the animal quietly following.

馴伏第五

綠楊陰下古溪邊,放去收來得自然;

日暮碧雲芳草地,牧童歸去不須牽。

***

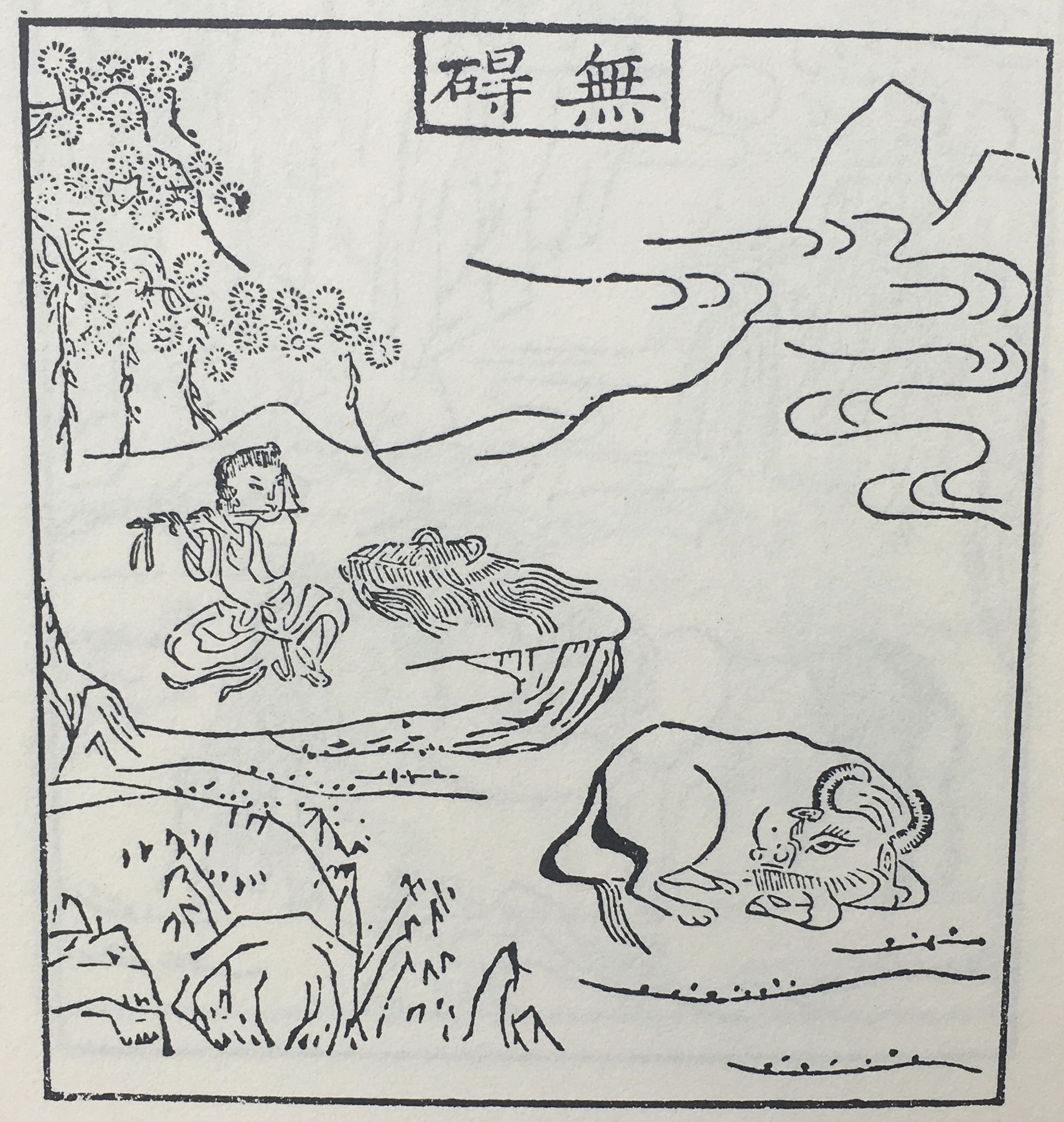

Six: Unimpeded

On the verdant field the beast contentedly lies idling his time away,

No whip is needed now, nor any kind of restraint;

The boy too sits leisurely under the pine tree,

Playing a tune of peace, overflowing with joy.

無礙第六

露地安眠意自如,不勞鞭策永無拘。

山童穩坐青松下,一曲升平樂有餘。

***

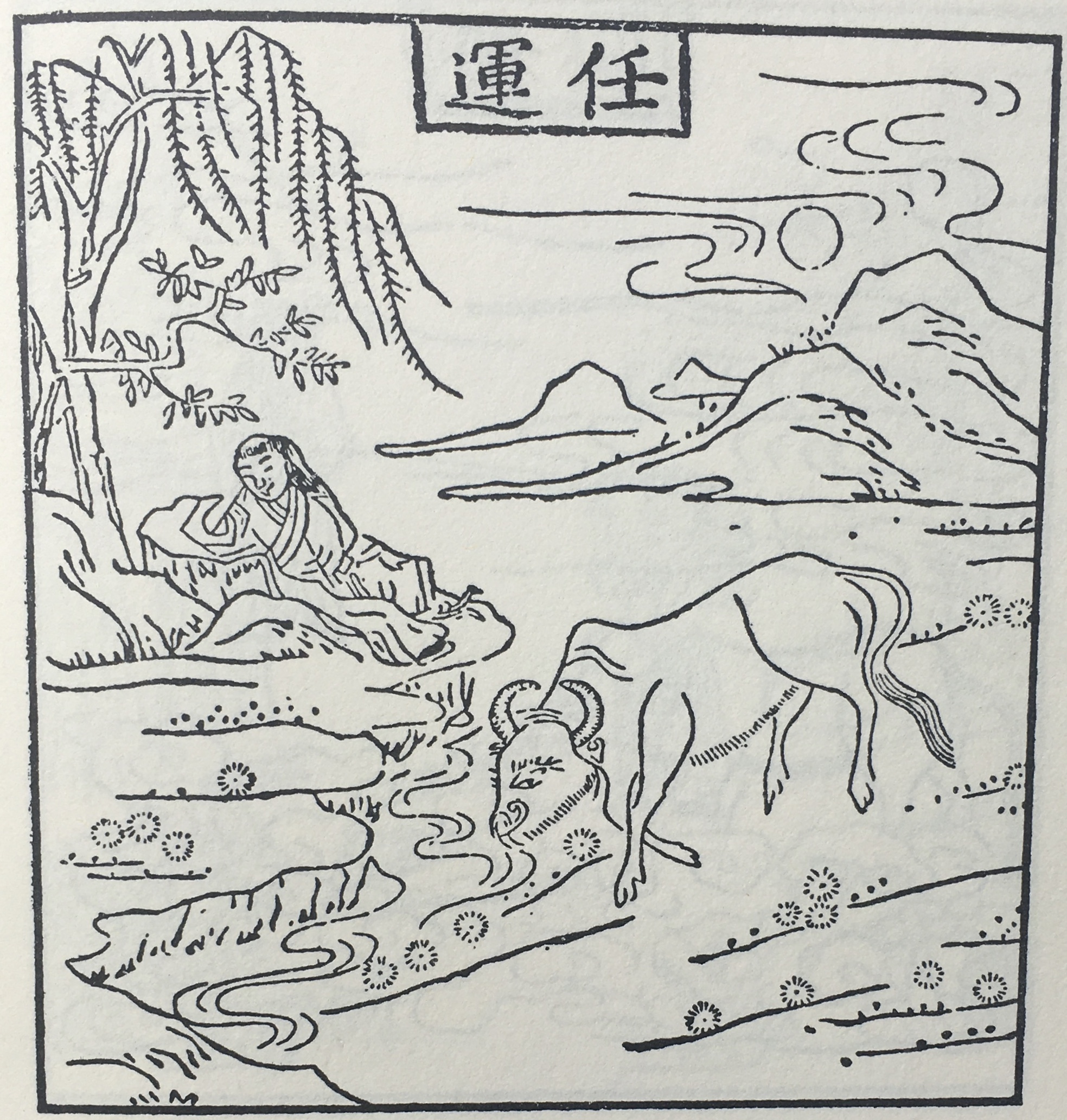

Seven: Laissez Faire

The spring stream in the evening sun flows languidly along the willow-lined bank,

In the hazy atmosphere the meadow grass is seen growing thick;

When hungry he grazes, when thirsty he quaffs, as time sweetly slides,

While the boy on the rock dozes for hours not noticing anything that goes on about him.

任運第七

柳岸春波夕照中,淡煙芳草綠葺葺;

饑餐渴飲隨時過,石上山童睡正濃。

***

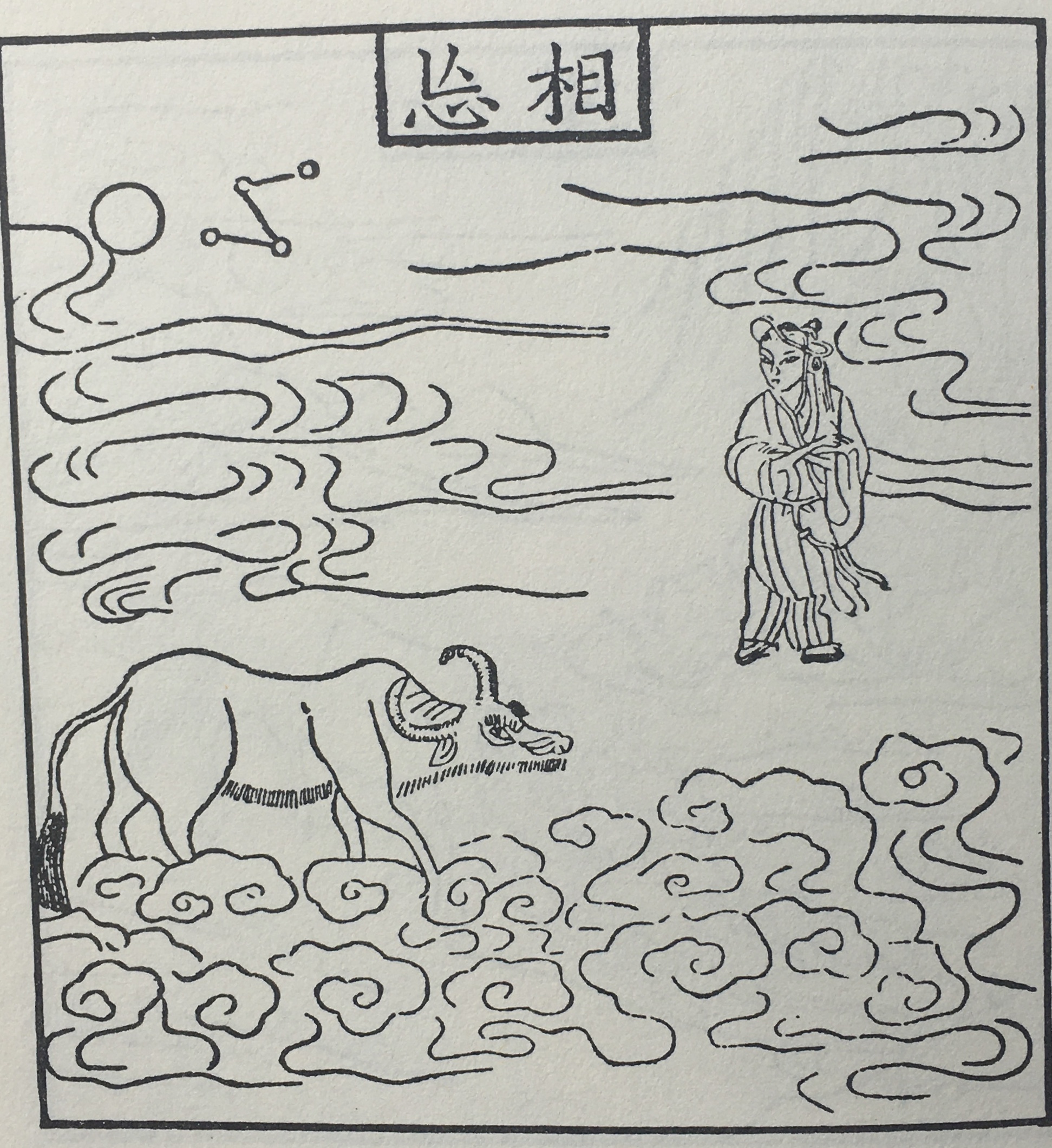

Eight: All Forgotten

The beast all in white now is surrounded by the white clouds,

The man is perfectly at his ease and care-free, so is his companion;

The white clouds penetrated by the moon-light cast their white shadows below,

The white clouds and the bright moon-light-each following its course of movement.

相忘第八

白牛常在白雲中,人自無心牛亦同;

月透白雲雲影白,白雲明月任西東。

***

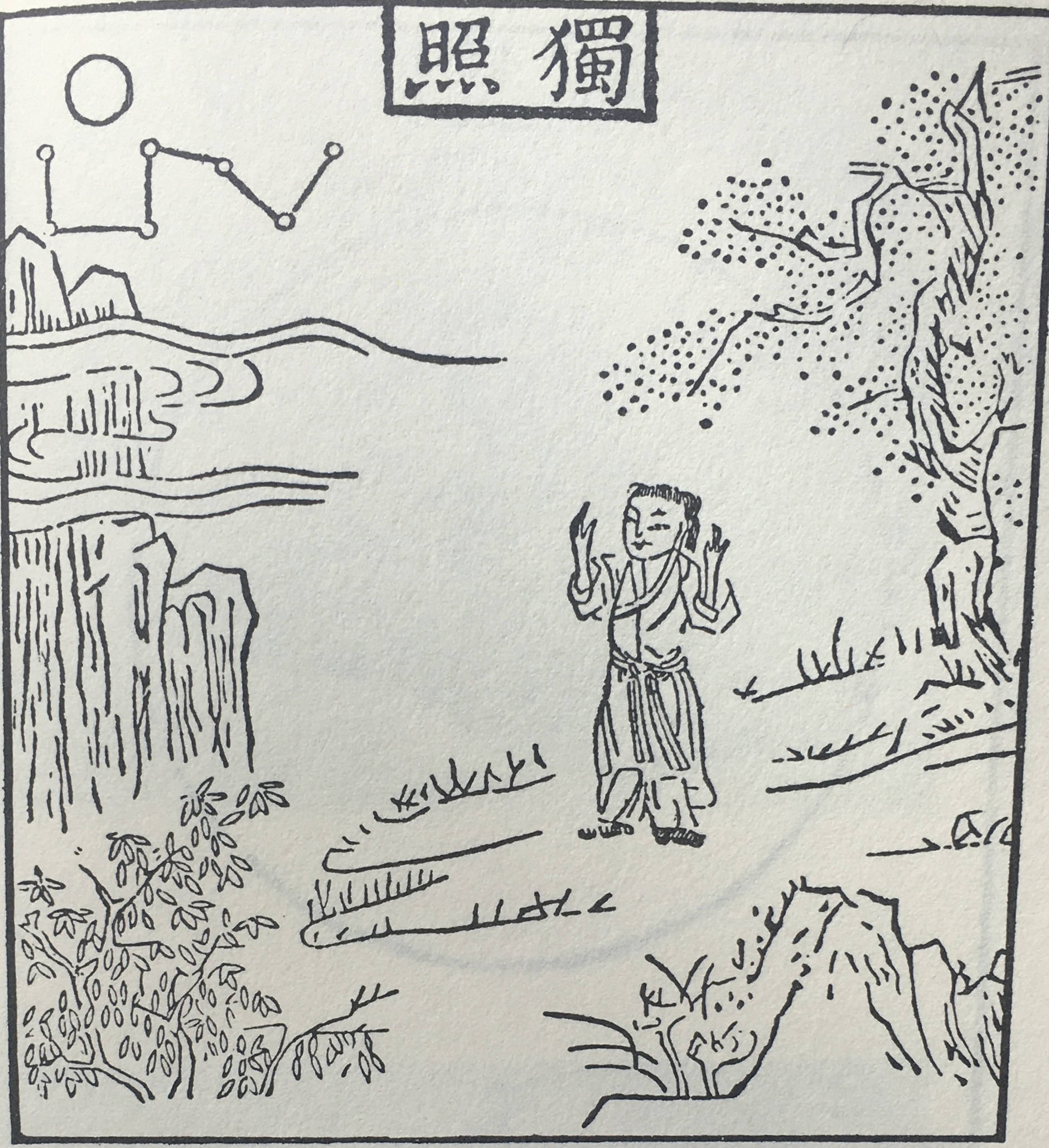

Nine: The Solitary Moon

Nowhere is the beast, and the oxherd is master of his time,

He is a solitary cloud wafting lightly along the mountain peaks;

Clapping his hands he sings joyfully in the moon-light,

But remember a last wall is still left barring his homeward walk.

獨照第九

牛兒無處牧童閑,一片孤雲碧嶂間;

拍手高歌明月下,歸來猶有一重關。

***

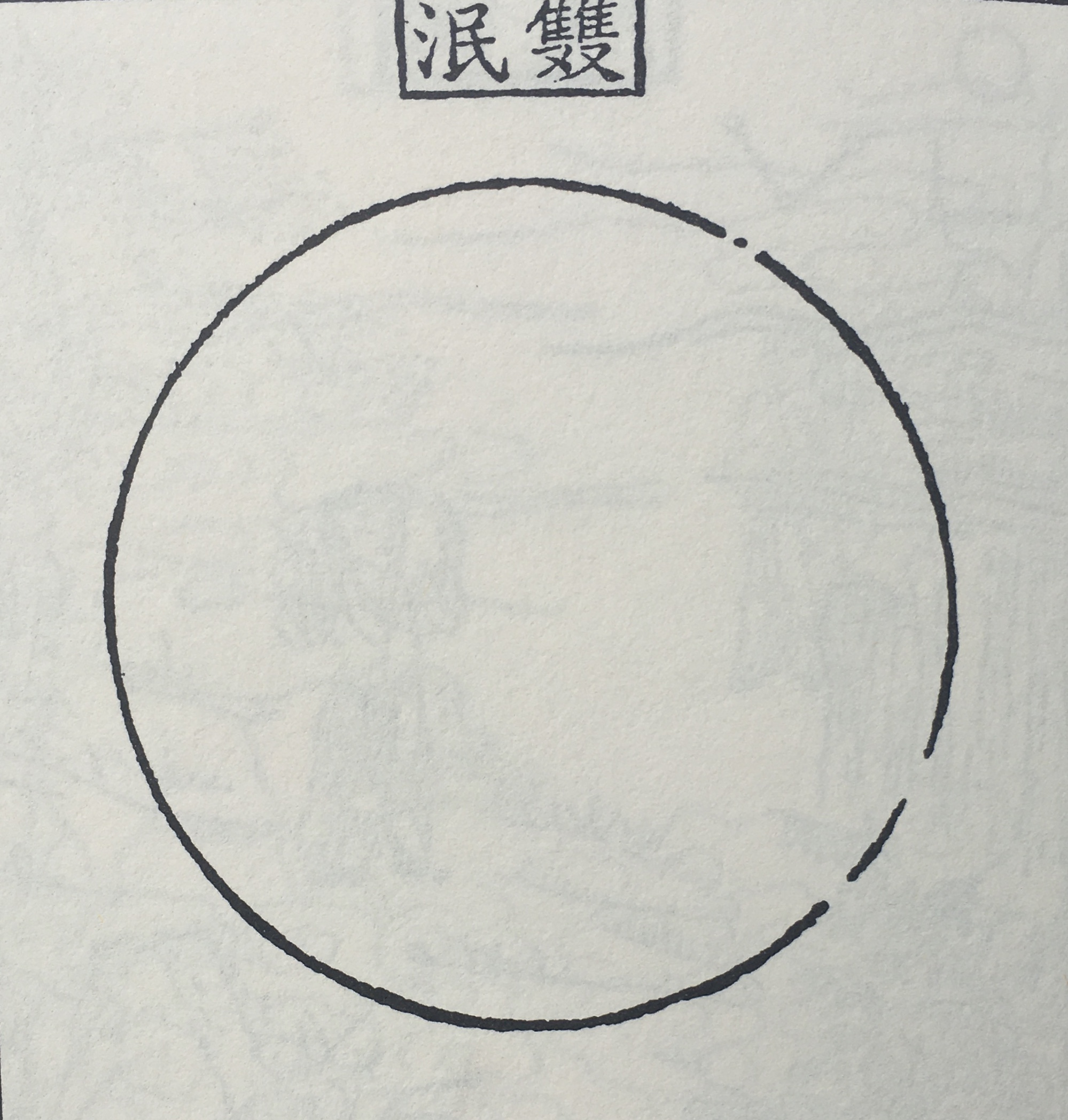

Ten: Both Vanished

Both the man and the animal have disappeared, no traces are left,

The bright moon-light is empty and shadowless with all the ten-thousand objects in it;

If anyone should ask the meaning of this,

Behold the lilies of the field and its fresh sweet-scented verdure.

雙泯第十

人牛不見杳無蹤,明月光含萬象空;

若問其中端的意,野花芳草自叢叢。

***

Source:

- ‘The Ten Oxherding Pictures’, translated by D. T. Suzuki, in Manual of Zen Buddhism, Kyoto: Eastern Buddhist Society, 1934; London: Rider & Company, 1950; and, New York: Grove Press, 1960. This version of the images and Suzuki’s translation are taken from the 1960 edition, pp.135-144