The following essay by Andrea Bachner is from A New Literary History of Modern China, edited by David Der-wei Wang, Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2017. We are grateful to the author, David Wang and to Belknap Press for permission to reprint this material.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

24 July 2018

***

Chapters from A New Literary History of Modern China

We are grateful to Belknap Press for permission to reprint four chapters from A New Literary History of Modern China:

- 1899: Oracle Bones, That Dangerous Supplement … , by Andrea Bachner

- 1946: On Literature and Collaboration, by Susan Daruvala

- 1965: Red Prison Files, by Jie Li 李潔

- 1983: Discursive Heat: Humanism in 1980s China, by Gloria Davies 黃樂嫣

See also Silent China & Its Enemies — Watching China Watching (XXX), China Heritage, 13 July 2018.

***

Note: Where relevant, Chinese characters and links have been added to the text. Minor stylistic modifications in keeping with the in-house style of China Heritage have also been made.

***

1899

Often, late at night, he would indulge alone, like an addict, in this secret pleasure of eating turtle flesh, quietly listening to the turtle’s speech, and making a private divination in order to test out this mysterious method. He would carve a message in oracle-bones script, seeking to recreate an ancient experience.

— Ng Kim Chew 黃錦樹, ‘Fish Bones’ 魚骸

***

Oracle Bones, That Dangerous Supplement …

Andrea Bachner

In the summer of 1899 — or so the legend goes — Wang Yirong (王懿榮, 1845-1900), a Qing dynasty official, purchased a concoction of ‘dragon bones’ 龍骨 as a treatment for malaria. Curious, Wang inspected this mysterious ingredient of traditional Chinese medicine, only to discover, to his amazement, that the ancient bone to be ground into his potion bore written marks. These marks looked like Chinese writing, though they were unlike any known Chinese script. In a scene that connects the medical and the cultural, shortly before China would surrender to the allied forces that crushed the Boxer Rebellion, China thus (re)discovered its oldest written archive: inscriptions on tortoise plastrons and ox scapulae dating from the late-Shang dynasty.

The discovery of oracle bones triggered a collecting frenzy that impelled Wang, soon followed by others, to purchase over a thousand specimens — almost as if, in the national catastrophe of the Boxer Rebellion and the impending defeat at the hands of the allied forces, the accumulation of fragments of a forgotten past served as tokens of cultural stability. After all, throughout the centuries, the act of collecting the artifacts of bygone days offered Chinese intellectuals a place within an imagined cultural continuum. We, of course, cannot know if the oracle bones actually healed Wang, or if he even ingested any after his find. What is certain, however, is that they ultimately could not ‘cure’ Wang of the effects of national humiliation, the sickness of the Chinese nation so often evoked during China’s rocky road to modernity. Not long after making his discovery, Wang would commit suicide. In the face of the impending defeat of the Qing at the hands of the allied forces, he jumped into a well, after previously attempting suicide by ingesting poison.

Intellectual infatuation with these strange bones did not cease with Wang’s death, and instead this would be merely the first act in a drama about cultural continuity in the context of China’s traumatic history. For instance, Liu E (劉鶚, 1857-1909), who was present when Wang made his discovery, later acquired a collection of about five thousand oracle bone pieces, including many of Wang’s own. In 1903, the same year Liu E began working on his famous novel The Travels of Lao Can 老殘遊記, Liu also published a partial catalogue of the oracle bones in his possession. In the form of ink rubbings, veritable analog copies of the originals, Liu E’s collection would give rise to a paper trail of catalogues, transcriptions, commentaries, and studies, and mark the beginning of a new discipline known as jiagu-ology 甲骨學, or the study of oracle bones.

Liu E’s catalogue inspired a variety of other scholars, including Luo Zhenyu (羅振玉, 1866-1940), who wrote a preface for it and went on to become one of the most eminent early voices in the field; Wang Guowei (王國維, 1877-1927), who catalogued part of Liu E’s collection for a subsequent owner and wrote several important works on oracle bones and Shang society; and Guo Moruo (郭沫若, 1892-1978), whose interest in the subject originated from reading Luo’s books in Japan. Oracle bones became the center of a radiating archive of artifacts, rubbings, and writings. In a time of uncertainty, change, and turmoil, they also knit Chinese intellectuals, often beyond the bounds of China proper, into a kind of imagined community, touched by the strange social and intellectual glue of these skeletal scraps and their mysterious inscriptions.

Even before the origin of these bones was traced to Anyang’s Xiaotun in Henan Province 河南安陽小屯村 in 1928, supposedly the site of the Shang capital Yin 殷墟, oracle bones had already replicated themselves in textual form, reshaping the archive of Chinese culture. Oracle bones quickly became a matter of national pride: from bone pieces that locals sold for profit to coveted pieces in individual collections, they ultimately became national treasures. As objects, oracle bones straddled the old antiquarian paradigm of individual collections and the birth of modern Chinese archeology as a science with national implications. Not only did they prove that a full- fledged Chinese writing system had existed more than three thousand years ago, the bones also confirmed historical elements recorded in Sima Qian’s (司馬遷, 135?-86 BCE) Records of the Grand Historian by providing tangible proof that the Shang dynasty existed — until the discovery, the Shang civilization had remained less veritable. The bones therefore bolstered Chinese cultural confidence at a time in which China’s integrity and traditions were at risk.

The idea of Chinese intellectuals in the early decades of the twentieth century fiddling with yellowed bone fragments, transcribing esoteric characters, or poring over catalogues of rubbings might convey an image of immersion in the past and obliviousness to the present. To tarry with Chinese writing of millennia ago at a time of intense debates around the possible abolition, or at least reform, of the Chinese language and script might seem anachronistic. When Hu Yuzhi (胡愈之, 1896-1986), a promoter of Esperanto to replace the Chinese written characters, fustigated stalwart supporters of the Chinese script in his essay ‘On Poisonous Discourse’ 有毒文談 of 1937, he called them ‘young and old loyalists enamored with bones’. Indeed, Wang and Luo were such bone fetishists, remaining loyal to the Qing dynasty after its fall in 1911 and even after their return to China following several years of exile in Japan. And yet, research on oracle bones did not just mean an escape from the strictures and disappointments of the present into the remote and timeless glory of the Chinese past.

Wang, better known for his interest in Arthur Schopenhauer’s (1788-1860) philosophy and his work on the Dream of the Red Chamber than for cross-referencing the genealogy of the Shang kings, and Guo, better known for his poetry inspired by Walt Whitman (1819-1892) than for his volumes on oracle bone vocabulary, were both modern thinkers. For them, oracle bones were not a topic of the past, but of the present and future. In his 1926 talk ‘The Past and Future of Chinese Archeology’, another eminent intellectual, Liang Qichao (梁啟超, 1873-1929), even used the charged term ‘revolution’ to highlight the historical importance of the discovery of oracle bones. To Liang and many of his contemporaries, these missives from the remote past, forgotten for millennia, marked the modernity of the present, and its superiority vis-à-vis another past whose traditions impacted the present:

As for these [oracle bones], Confucius had not seen them, but we have; Confucius did not know about them, but we do; Confucius had it wrong, but we can set it right.

As newly discovered knowledge and a reason for national pride, oracle bones were very much part of the Chinese present. Insofar as studying oracle bones offered a different perspective on the past, and thus a different appreciation of the present, by turning China’s gaze backward it actually oriented it toward the future. The year 1899 marks not so much an incisive date as a strange temporal twist. Its temporality is reversed in the forward-looking optimism of Liang’s vision of China’s glorious future in his unfinished 1902 novel, The Future of New China 新中國未來記. In contrast to Liang’s leap into the future that allows for a new perspective on the past, as textual and symbolic relics, oracle bones constituted a new way of connecting with the past that allowed a leap into the future.

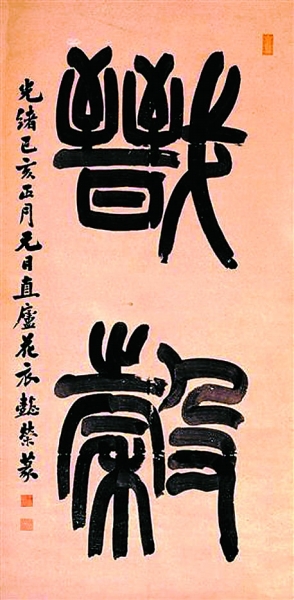

The temporal warp around oracle bones in the first decades of the twentieth century echoes their purpose for the Shang, given that, as divinatory tools, they offered the possibility of transcending the limits and strictures of time itself. Holes drilled into the bone surfaces, then exposed to a heat source, caused the scapulae or plastrons to crack with a snapping sound, the voice of the turtle — the character for divining 卜 combines the image of a crevice with the sound puk of cracking. These ‘natural’ inscriptions — supplemented by carved characters to document the context and outcome of pyromancy with bones — were communications from deities and ancestors, voices conjured up from the past that allowed glimpses into the future.

Oracle bones are often treated as the essence of cultural specificity by both Chinese and non-Chinese, but their temporal logic reflects a more general tendency at large in global modernities. Even as modernity began to conceive of temporality largely in linear terms, many modern thinkers, writers, and artists remained obsessed with the contemporaneity of past and present, for instance in the guise of primitivism. In a short story by contemporary Malaysian Chinese writer Ng Kim Chew (黃錦樹, 1967-), ‘Inscribed Backs’ 刻背, the semi-ironic equation of European modernism and Chinese intellectuals’ obsession with oracle bones serves as a whimsical side story. In a brothel in Singapore at the beginning of the twentieth century, a quaint Chinese intellectual (reminiscent of Wang) immersed in the project of writing a new Dream of the Red Chamber in oracle bone script on turtle shells inspires an English visitor to dream of creating a novel superior to Ulysses, tattooed onto the backs of coolie laborers. In the colonial space of Singapore evoked in Ng’s story, two writers with different cultural backgrounds equally seek literary innovation through a return to archaic inscription techniques.

In an earlier short story, ‘Fish Bones’ 魚骸, that opens with a series of quotes from famous scholars of jiagu-ology, Ng had already interrogated the symbolic charge of oracle bones for the meaning of Chinese culture in the present. The story’s protagonist, a Malaysian Chinese who teaches at a Taiwanese university, enacts nightly rituals of plastromancy: he kills, cooks, and eats turtles, then uses their shells for oracle bone divination. What might seem, at first glance, a performance of identity intended to move an individual at the margins of Chinese culture closer to its imaginary center becomes an indictment of an essentialist notion of ‘Chineseness’. Not only does the story’s protagonist identify with the turtles — inspired by research on the possible southern provenance of some of the tortoise shells — that are sacrificed to, yet also bearers of, Chinese culture, his ritual also commemorates his older brother, who died in the Communist rebellion against colonial forces in British Malaya in the 1950s.

Oracle bones, then, symbolize personal and cultural loss for the protagonist, but they are also fetishized objects of desire. Trauma and sexual awakening coincide when the protagonist, as an adolescent, chances upon the skeleton of his dead brother in the jungle, surrounded by turtle shells. In the adolescent’s act of masturbation, the dead exoskeleton — a relic from the site of his brother’s death, as well as a token of ‘Chineseness’ both coveted and despised — returns to life:

When he awoke, he removed the tortoise shell he had hidden in his bureau and, without thinking, placed it over his erect penis. In this way he was able to reach an unprecedented orgasm, as white semen spurted from his own swollen red ‘turtle head’ 龜頭.

Fuck oracle bones! Fuck ‘Chineseness’! Or so the story’s bone maneuvers seem to tell us. And yet, as the strange pharmakon of Chinese modernity, as the fetishized or desecrated symbol of Sinocentrism, oracle bones will not cease to haunt Chinese culture … as a dangerous supplement.

***

Bibliography:

- Chen Weizhan, Jiaguwen lunji (Shanghai, 2003)

- Gu Yinhai, Jiaguwen: Faxian yu yanjiu (Shanghai, 2002)

- Hu Yuzhi, ‘You du wen tan”’(1937), in Hu Yuzhi wenji (Beijing, 1996), 3: 549–555

- David N. Keightley, Sources of Shang History: The Oracle-Bone Inscriptions of Bronze Age China (Berkeley, CA, 1978)

- Liang Qichao, ‘Zhongguo kaoguxue zhi guoqu ji jianglai’ (1926), in Liang Qichao quanji (Beijing, 1999), 9: 4949-4925

- Ng Kim Chew, ‘Inscribed Backs’ and ‘Fish Bones’, in Slow Boot to China and Other Stories, ed. and trans. Carlos Rojas (New York, 2016), pp.237-304 and 97-120

***

Source:

- A New Literary History of Modern China, edited by David Der-wei Wang, Belknap Press/Harvard University Press, 2017, pp.156-161