Viral Alarm

Viral Alarm is the title of China Heritage Annual 2020. That series focussed on the COVID-19/ Coronavirus/ Wuhan Influenza epi- / pandemic and its significance both in China as well as in China in the world.

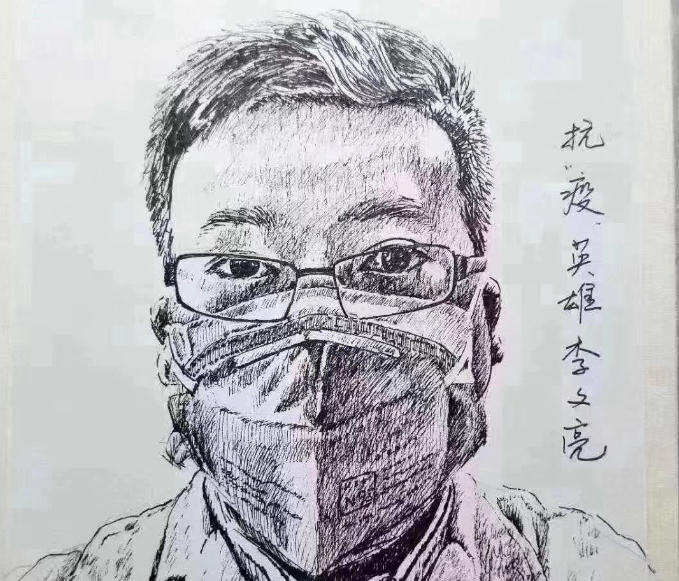

Today mark’s three years since the death of Dr Li Wenliang 李文亮 from COVID-19. We commemorate China’s famous epidemic whistleblower with an essay and a translation originally published by The China Project. We are grateful to Jeremy Goldkorn for permission to reprint this material.

— Geremie R. Barmé,

Editor, China Heritage

7 February 2023

***

Related Material:

- Viral Alarm — China Heritage Annual 2020

- Pablo Robles, Vivian Wang, and Joy Dong, In China’s Covid Fog, Death of Scholars Offer a Clue, New York Times, 5 February 2023

- Inside the Final Days of the Doctor China Tried to Silence, New York Times, 6 October 2022

Li Wenliang: The man who was wrong to have been right

Dr. Lǐ Wénliàng 李文亮 is the doctor who tried to warn his colleagues about the spread of COVID-19 in Wuhan in early 2020, was silenced by the authorities, and forced to write a self-criticism. This is a translation of that document by renowned Sinologist Geremie Barmé to mark Li’s death three years ago this week.

— Jeremy Goldkorn, 1 February 2023

***

February 1, 2023, marks three years since Dr. Lǐ Wénliàng 李文亮 posted his last message: “I got a positive nucleic-acid test today. The dust has settled, and the diagnosis has finally been confirmed.” A week later, on February 7, 2020, COVID-19 killed him.

On December 30, 2019, the same day that China’s Contagious Disease Commission circulated a memo to hospitals in Wuhan to be on the lookout for a new form of pneumonia, Li saw a patient’s report indicating the presence of a form of the SARS coronavirus. At 17:43 that day, Li told a private WeChat group of his medical school classmates, “Seven confirmed cases of SARS were reported from Huanan Seafood Market.” He also posted the patient’s examination report and CT scan image to the group. At 18:42, he added, “It has been confirmed that they are coronavirus infections, but the exact virus strain is being subtyped,” and suggested to his classmates that they alert their families.

When news of Li’s remarks spread, his superiors put him under investigation and, on January 3, 2020, he was interrogated by the Wuhan police. As a result, Li was issued with a formal warning and was censured for “publishing untrue statements.” He was also made to sign a letter of repentance. As the epidemic spread, and despite an official attack on him, unofficially, Dr. Li’s “whistle-blowing” was widely praised. Although his warning had been ignored and suppressed, Li’s confession was soon vitiated by events. On January 31, Li released details of his interrogation on social media.

When he was under investigation, Li, who was a Party member, had been required to write a self-criticism. Self-criticisms, be they in writing or in verbal form, are the lifeblood of the Communist Party. They are integral to the network of guidance, control, and censure that encompasses the education system, government operations, work life, and local policing. Formulaic and trite though they may be, self-criticisms are a key sociopolitical lubricant in the machinery of the party-state. There is a stilted artfulness to their composition, one that many people learn from an early age. A self-criticism routinely catalogs errors, interrogates personal failings, and offers an admission of guilt that invariably concludes with a solemn undertaking not to sin in the future.

The self-criticism has been a feature of Communist Party life since the Yan’an Rectification Movement starting in 1942, when all Party members at the wartime guerrilla base were required to align their thinking with a new form of Sinified Marxism that would be known as “Mao Zedong Thought.” At the time, an old Buddhist term was employed to describe what was required: Everyone had to demonstrate their unquestioning submission to the Party line “verbally, in writing, as well as in the heart” (口服、手服、心服). Since 1949, only denunciations of other people have been able to match the volume and frequency of self-criticisms and confessions as the most expansive category of China’s secretive and voluminous written culture.

In April 2020, Li was officially recognized as a martyr. In June 2020, Fù Xuějié 付雪洁, his widow, gave birth to their second son.

As the coronavirus continues to ravage China and the world on the third anniversary of Li’s death, we offer a translation of his confession and recall the official Chinese claim that, from January 7, 2020, Xí Jìnpíng 习近平 was “personally supervising and personally directing” (亲自指挥、亲自部署) China’s COVID response. Li, like everyone else in China, was subordinated to the dialectical will (and whims) of the leader — something known as zhǎngguān yìzhì 长官意志. And, as the Sinologist Simon Leys observed:

Dialectics is the jolly art that enables the Supreme Leader never to make mistakes — for even if he did the wrong thing, he did it at the right time, which makes it right for him to have been wrong, whereas the Enemy, even if he did the right thing, did it at the wrong time, which makes it wrong for him to have been right.

Of the tens of millions of self-criticisms written over the years, Dr. Li Wenliang’s confession stands out as one of the most heartbreakingly consequential and blood-stained. More important, however, is his epitaph, a quotation attributed to Li that was shared widely on the Chinese internet following his death:

“For a society to be healthy, there needs to be more than one voice.”

一个健康的社会不应该只有一种声音。

— Geremie R. Barmé

My Reflections and Self-Criticism

— my role in the present incident regarding the leaking of inaccurate information related to the “Wuhan Pneumonia of Uncertain Origin”

2019.12.30

Li Wenliang

Despite the fact that the information I had to hand had not been verified, I nonetheless took it upon myself to tell members of the group chat of my former university classmates that “seven cases of SARS have been confirmed at the Huanan Seafood Market.” One of those classmates circulated a screenshot of my post outside of our group and that resulted in widespread public panic. This had a negative impact on the investigations being undertaken by the Hygiene Commission as well as ongoing diagnostic work. As a result of a probing self-analysis I now realize that:

- I lack the kind of political awareness required of a Party member;

- I lack an adequate understanding of contemporary internet culture and the speed with which inaccurate information can be disseminated;

- I lack knowledge of medical matters that are beyond my immediate area of specialization; and,

- I lack an ability to adequately assess information.

Having now measured my actions against the stipulations of the Party Constitution, relevant regulations and the guidance contained in key speeches [made by Xi Jinping and other leaders], I have been able to ascertain just where I have fallen short. In light of this, I have undertaken a detailed self-examined and, following deep reflection, I offer the following self-criticism:

1. In regard to my inadequate political acuity I have come to recognize that my study of the Party Constitution and relevant regulations was neither sufficiently systematic nor rigorous. Furthermore, I have failed to apply the relevant aspects of Party theory to guide my actions.

Article Three in Chapter One of the Constitution of the Chinese Communist Party stipulates that Party members must: ‘Consciously observe Party discipline, with utmost emphasis placed on the Party’s political discipline and rules, set a fine example in abiding by the laws and regulations of the state, strictly protect Party and state secrets, execute Party decisions, comply with Party decisions on job allocation, and readily fulfill the Party’s tasks.’

I failed to critically scrutinize or confirm the information that I had at hand in a timely fashion. I too readily gave credence to unverified data, which I then disseminated in a chat group of my classmates. I also failed to appreciate in a timely fashion:

- The potentially serious consequences that might result from that information being leaked;

- The ongoing sensitivity of SARS;

- The profound impact that the SARS epidemic of 2003 had on the livelihood and health of the broad masses; and,

- The devastating losses suffered by the national economy.

The state has protocols in place regarding the announcement and dissemination of information related to public health emergencies. These clearly state that, ‘In the case of an outbreak of an infectious disease, its spread or any other public health emergency within their jurisdiction, the relevant public health authorities and government of each province, autonomous region and directly administered municipality are to make a timely and accurate announcement.’

That means, therefore, that as an individual I simply have no right to provide any information, let alone information that is inaccurate. It behooves me to maintain absolute unity both in thought and in deed with the Central Committee of the Party.

2. An insufficient appreciation of the manner in which information can be disseminated online. I now appreciate that with the proliferation of digital technology, in particular smartphones, mobile internet connections are constantly evolving. Rumors concerning medical emergencies invariably result in mass panic, the undermining of the government’s credibility, and social disorder. The massive volume of images, short videos and texts on social media such as WeChat and the fragmentation of news sources can easily spark widespread popular curiosity and misunderstandings. As a result, news of a medical emergency can spread rapidly and rumors can readily gain a foothold. Within the space of a few hours, the texts and images that I had posted to my chat group had spread to other provinces and were even being reposted by the international media. This had a negative impact both on the authorities and on the relevant health and propaganda organizations. I was not mentally prepared for any of this and I feel profoundly regretful and remorseful about it.

3. I have not studied or sufficiently appreciated the relevant laws and regulations pertaining to the use of WeChat. Starting on 8 October 2017, the ‘Administrative Provisions on the Information Services Provided through Online Chat Groups’ and ‘Administrative Provisions on the Information Services Provided through Official Accounts of Internet Users’, previously promulgated by the National Cyberspace Administration of China, went into effect. These new regulations clearly stipulated how information can and should be dealt with and disseminated by online chat groups.

Creating and spreading rumors can lead to social panic, have a negative impact on people’s daily lives and their work behaviors. The Internet is not beyond the law.

Article 25 of the ‘Public Security Administration Punishments Law of the People’s Republic of China’ stipulates that those who ‘spread rumors, make erroneous reports of incidents, viruses, or police matters or by other means purposefully undermine social order’ can be detained or fined. I am now deeply aware of the fact that WeChat is a platform with numerous users, it has a broad impact and that a negative piece of information can have an immediate and profound impact. In the future I am determined not to disseminate any information that contravenes the regulations, firmly obey all relevant laws and be sure ‘not cross the line’.

In my future work and studies I undertake to constantly reflect critically on my thoughts, words and deeds. I undertake to engage with an ongoing self-critical review of myself. I will humbly learn from the example set by the leaders of my work unit and my comrades. I will be steadfast in my support for the Party’s ideals; I will give no credence to rumors; I will not spread rumors. I will constantly measure my actions against the relevant stipulations of the Party Constitution, its regulations and the guiding spirit of the leaders’ speeches. I resolve to apply myself to the study of political theory, enhance my awareness of ‘political sensitivity’, and police my actions in every way so that I can be a Party member worthy of the name.

***

Chinese text of Dr Li’s self-criticism:

关于当前”武汉不明原因肺炎”事件中不实消息外传的反思与自我批评

我在消息来源不确切的情况下,自以为是的转发了关于“华南海鲜市场确诊了7例SARS”的不实消息到大学同学交流群,后被不明同学截图外传,造成了公众的恐慌,对卫健委及相关部门的调查、诊治工作起到了负面作用。对此我深刻反思,认识到作为一名党员我缺乏应有的政治敏說性,对互联网发达的当下信息的传播规律没有足够认识,对非自己专业的疾病认识不足,缺乏辨别信息能力等。对此,我对照觉章、党规及系列讲话精神,找差距,检视自身,做深刻反思与自我批评。

1. 缺乏应有的政治敏锐性。对党章、觉规学习不够系统全面,不能充分利用相关理论直到实践。

觉章第一章,第三条明确规定觉员必须“自觉遵守党的纪律,首先是觉的政治纪律和政治规矩,模范遵守国家的法律法规,严格保守党和国家的秘密,执行党的决定,服从组织分配,积极完成党的任务。”对相关信息未能及时辦别、核实,对外来信息轻易信以为真,并发布在同学群中,未能及时认识到信息外泄的可能及其带来的严重后果,SARS极其敏感,2003年的流行对广大人民群众生命健康造成了巨大威胁,对国家经济造成严重损失。国家对突发公共卫生事件的信息发布早有规定,对于相关信息必须由“各省、自治区、直辖市卫生行政部门对在本行政区域内发生传染病暴发、流行以及发生其他突发公共卫生事件及时、准确地发布。”作为个人,我无权发布相关信息,更不能发布不实信息。我应当在思想和行动上与党中央保持一致。

2.对突发事件互联网传播规律缺乏足够认识。随着计算机、特别是智能手机的普及,移动互联网发展日新月异,突发事件的谣言传播往往会引发群体性恐慌蔓延、政府威信降低、社会秩序混乱等问题。微信等自媒体传播的图片、视频、文字等信息量大,信息碎片化,极易引发民众的好奇心及误解。导致突发事件的关注度迅速上升,使谣言进一步扩散。短短几个小时内,我发送的相关文字及图片信息已传到外省甚至境外媒体都有转发。为政府及相关卫生、宣传部门工作造成了不利影响。这都是我所始料未及的,对造成的影响深深自责、内疚。

3. 对微信使用中应遵守的法律法规学习不足。2017.10.8日起,国家互联网信息办公室印发的 《互联网群组信息服务管理规定》和《互联网用

户公众账号信息服务管理规定》开始施行。新规明确规定应规范群组网络行为和信息发布。造谣或传谣极易引发社会恐慌,影响正常生活和工作秩序。互联网不适法外之地。《中华人民共和国治安管理处罚法》 第二十五条规定“对散步谣言,谎报险情、疫情、警情或者其他方法故意扰乱公共秩序的”可处以拘留或罚款。我深刻认识到微信平台用户基数大、传播面广,违法有害信息一旦传播影响更为恶劣,我以后一定坚决不发布涉嫌违法信息,严格遵守相关法律规定,不”越线”。

在今后的工作和学习中,我一定不断进行反思和自我批评,虚心向科室领导及其他党员同志学习,坚定理想信念,不信谣、不传谣,时时对照觉章、党规及系列讲话精神要求自己,加强政治理论学习,紧细”政治敏感性”这根弦,规范自身行为,做一名合格党员。