Readings in New Sinology

For my own part, I can never get enough Nothing to do.

— G.K. Chesterton

閒 xian: idleness, idly. A very much used word. Thus one’s ‘hands’ and ‘mind’ can both be ‘idle,’ or the hands may be idle while the mind is busy, or the mind may be idle while one’s hands are busy.

— Lin Yutang

In his introduction to Two Letters from The Stone (China Heritage, 19 March 2018) John Minford noted that:

As part of our recently completed Wairarapa Academy Symposium ‘Dreaming of the Manchus’ 八旗夢影, which took place at Longwood Estate near Featherston in late February this year, we held a number of informal Translation Salons 竹林譯苑. For these we prepared and distributed a series of Wairarapa Readings 白水札記.

The first Wairarapa Reading published by China Heritage featured two letters addressed to Jia Bao-yu 賈寶玉 in Chapter 37 of The Story of the Stone 紅樓夢 translated by David Hawkes. ‘Occupied with Idleness’, the second Wairarapa Reading in China Heritage, continues our mediation on the theme of Idleness by introducing works by Bo Yuchan 白玉蟾 of the Song dynasty, Li Mi’an 李密庵 of the Ming and Jin Shengtan 金聖嘆 of the Qing. They are all translated by Lin Yutang 林語堂 in The Importance of Living (1937).

As we noted in the introduction to Idleness 閒 in Heritage Glossary, from the late 1920s, a number of leading writers and cultural figures, including Zhou Zuoren 周作人 and Lin Yutang, through lectures, essays and edited works (books and journals) attempted to counter the narrow cultural nationalism and propagandist tenor both of elite and of mass culture that plagued radical and conservative politics alike. Instead of the mob mentality, or class conflict, they advocated ‘self-expression’ 性靈 and a ‘leisurely’ 閒適 style of intimate essay and prose writing, one in which the individual could find a voice. They identified cultural exemplars among international writers as well as in the Chinese tradition. The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢, discussed elsewhere on this site, were also paragons. Lin Yutang in particular promoted a written language that embraced the belles lettres style of Ming and Qing prose and was able to express contemporary concerns. He called this yuluti 語錄體.

Partially preserved in post-1949 Taiwan-Chinese culture, the literature of leisure 閒適文學 and the pursuit of non-conformist self-expression eventually also found an outlet on Mainland China from the 1980s. The de-militarisation of society (but not politics) from that time, and the surge in mercantile pursuits meant that Other China — one not entirely beholden to the Communist party-state — could seek and find succour in a revival of long-forgotten literary tastes and personal styles.

Writers like Zhou Zuoren and Lin Yutang were derided for their escapism and frivolous, indulgent concern for what the artist and essayist Feng Zikai 豐子愷 called ‘protecting the heart’ 護心. Their work, once decried as ‘idle pursuits’ 閒情逸致 has outlived the furiously busy revolutionaries and the evanescent politics of their day. It resonates with readers still.

***

In ‘A Way of Living’ written in 1995, Simon Leys remarks:

From the earliest antiquity, leisure was always regarded as the condition of all civilised endeavours. Confucius said: ‘The leisure from learning should be devoted to politics and the leisure from politics should be devoted to learning.’ Government responsibility and scholarly wisdom were the twin prerogatives of a gentleman and both were rooted in leisure. The Greeks developed a similar concept — they called it scholê; this word literally means the state of a person who belongs to himself, who has free disposition of himself and therefore: rest, leisure; and therefore, also, the way in which leisure is used: study, learning; or the place where study and learning are conducted: study-room, school (actually scholê is the etymology of ‘school’). In ancient Greece, politics and wisdom were the exclusive province of the free men, who alone enjoyed leisure. Leisure was not only the indisputable attribute of ‘the good life’, it was also the defining mark of a free man. In one of Plato’s dialogues, Socrates asks rhetorically: ‘Are we slaves, or do we have leisure?’ — for there was a well-known proverb that said: ‘Slaves have no leisure.’

From Greece, the notion passed to Rome; the very concept of artes liberales again embodies the association between cultural pursuits and the condition of a free man (liber), as opposed to that of a slave, whose skills pertain to the lower sphere of practical and technical activity. …

Now the ironical paradox of our age, of course, is that the wretched lumpenproletariat is cursed with the enforced leisure of demoralising and permanent unemployment, whereas the educated elite, whose liberal professions have been turned into senseless money-making machines, are condemning themselves to the slavery of endless working hours — till they collapse like overloaded beasts of burden.

— The Angel & the Octopus, 1999, pp.276-278

***

Readings in New Sinology celebrate the variety and vivacity of China’s literary heritage while engaging with aspects of contemporary China. The readings introduces literary texts and translations that are aimed at students of traditional Chinese letters as well as modern China who are interested in the rich cultural world that lies beyond the narrow confines and demands of contemporary institutional pedagogy and media punditry. They also reflect our long-term interest in ‘cultivation’ 修養.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

23 March 2018

Note:

- Standard Chinese Hanyu pinyin romanisation is used throughout. — Ed.

The Hall of Idleness

慵庵銘

Bo Yuchan 白玉蟾

The translator Lin Yutang says this inscription is ‘a rather extravagant example of the praise for idleness’, but he writes that:

The idle life, so far from being the prerogative of the rich and powerful and successful …, was in China an achievement of high-mindedness, a high-mindedness very near to the Western conception of the dignity of the tramp who is too proud to ask favours, too independent to go to work, and too wise to take the world’s successes too seriously. This high-mindedness came from, and was inevitably associated with, a certain sense of detachment toward the drama of life; it came from the quality of being able to see through life’s ambitions and follies and the temptations of fame and wealth.

— The Importance of Living, p.158

The Hall of Idleness

I’m too lazy to read the Taoist classics,

for Tao doesn’t reside in the books;

Too lazy to look over the sutras,

for they go no deeper in Tao than its looks.

The essence of Tao consists in

a void, clear and cool,

But what is this voice except being

the whole day like a fool?

Too lazy am I to read poetry,

for when I stop, the poetry will be gone;

Too lazy to play on the ch’in,

for music dies on the string where it’s born;

Too lazy to drink wine, for beyond

the drunkard’s dream there are rivers and lakes;

Too lazy to play chess,

for besides the pawns there are other stakes;

Too lazy to look at the hills and streams,

for there is a painting within my heart’s portals;

Too lazy to face the wind and the moon,

for within me is the Isle of the Immortals;

Too lazy to attend to worldly affairs,

for inside me are my hut and possessions;

Too lazy to watch the chaining of the seasons,

for within there are heavenly processions.

Pine trees may decay and rocks may rot;

but I shall always remain what I am.

Is it not fitting that I call this

The Hall of Idleness?

慵庵銘

丹經慵讀,

道不在書。

藏教慵覽,

道之皮膚。

至道之要,

貴乎清虛。

何謂清虛,

終日如愚。

有詩慵吟,

句外腸枯。

有琴慵彈,

弦外韻孤。

有酒慵飲,

醉外江湖。

有棋慵奕,

意外干戈。

慵觀溪山,

內有畫圖。

慵對風月,

內有蓬壺。

慵陪世事,

內有田廬。

慵問寒暑,

內有神都。

松枯石爛,

我常如如。

謂之慵庵,

不亦可乎。

— translated by Lin Yutang

***

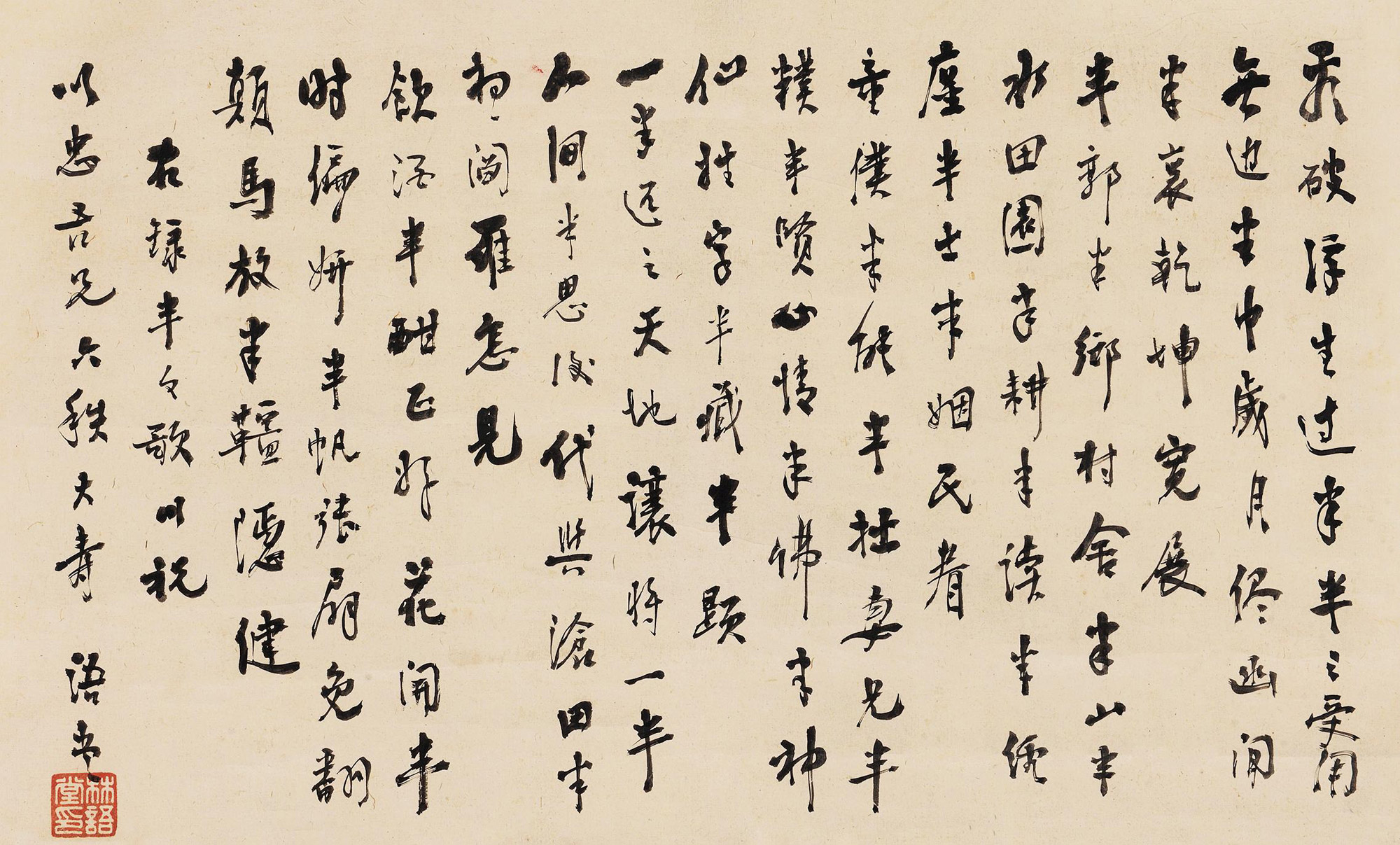

The Half-and-Half Song

半半歌

Li Mi’an 李密庵

‘The Half-and-Half Song’ by the Qing-era writer Li Mi’an was, like the poem by Bo Yuchan above, celebrated and translated by Lin Yutang in The Importance of Living. The Chinese version of Lin’s book has introduced contemporary readers to these, and other, long-forgotten works. As Lin observes when introducing Li’s poem:

We have here, then, a compounding of Taoistic cynicism with the Confucian positive outlook into a philosophy of the half-and-half. And because man is born between the real earth and the unreal heaven, I believe that, however unsatisfactory it may seem on the first look to a Westerner, with his incredibly forward-looking point of view, it is still the best philosophy, because it is the most human.

— The Importance of Living, pp.117-118

The Half-and-Half Song

By far the greater half have I seen through

This floating life — ah, there’s the magic word —

This ‘half’ — so rich in implications.

It bids us taste the joy of more than we

Can ever own. Halfway in life is man’s

Best state, when slackened pace allows him ease.

A wide world lies halfway ‘twixt heaven and earth;

To live halfway between the town and land,

Have farms halfway between the streams and hills;

Be half-a-scholar, and half-a-squire, and half

In business; half as gentry live,

And half related to the common folk;

And have a house that’s half genteel, half plain,

Half elegantly furnished and half bare;

Dresses and gowns that are half old, half new,

And food half epicure’s, half simple fare;

Have servants not too clever, nor too dull;

A wife who is not too ugly, nor too fair.

— So then, at heart, I feel I’m half a Buddha,

And almost half a Taoist fairy blest.

One half myself to Father Heaven I

Return; the other half to children leave —

Half thinking how for my posterity

To plan and provide, and yet minding how

To answer God when the body’s laid at rest.

He is most wisely drunk who is half drunk;

And flowers in half-bloom look their prettiest;

As boats at half-sail sail the steadiest,

And horses held at half-slack reins trot best.

Who half too much has, adds anxiety,

But half too little, adds possession’s zest.

Since life’s of sweet and bitter compounded,

Who tastes but half is wise and cleverest.

半半歌

看破浮生過半

半之受用無邊

半中歲月盡幽閒

半里乾坤寬展

半郭半鄉村捨

半山半水田園

半耕半讀經廛

半土半姻民眷

半雅半粗器具

半華半實庭軒

衾裳半素半輕鮮

餚饌半豐半儉

童僕半能半拙

妻兒半樸半賢

心情半佛半神仙

姓字半藏半顯

一半還之天地

讓將一半人間

半思後代與滄田

半想閻羅怎見

飲酒半酣正好

花開半時偏妍

帆張半扇免翻顛

馬放半僵穩便

半少卻饒滋味

半多反厭糾纏

百年苦樂半相參

會佔便宜只半

— translated by Lin Yutang

***

Thirty-three Happy Moments

不亦快哉三十三則

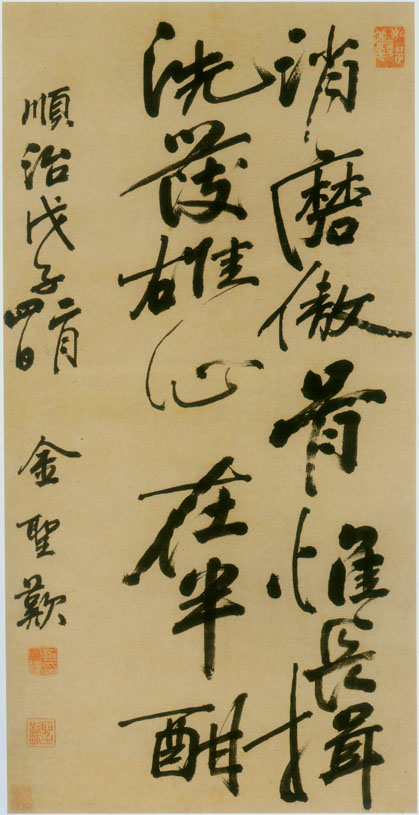

Jin Shengtan 金聖嘆

Jin Shengtan, that great impressionistic critic of the seventeenth century, has given us, between his commentaries on the play Western Chamber 西廂記, an enumeration of the happy moments which he once counted together with his friend when they were shut up in a temple for ten days on account of rainy weather. These, then, are what he considers the truly happy moments of human life, moments in which the spirit is inextricably tied up with the senses:

1. It is a hot day in June when the sun hangs still in the sky and there is not a whiff of wind in the air, nor a trace of clouds; the front and back yards are hot like an oven and not a single bird dares to fly about. Perspiration flows down my whole body in little rivulets. There is the noonday meal before me, but I cannot take it for the sheer heat. I ask for a mat to spread on the ground and lie down, but the mat is wet with moisture and flies swarm about to rest on my nose and refuse to be driven away. Just at this moment when I am completely helpless, suddenly there is a rumbling of thunder and big sheets of black clouds overcast the sky and come majestically on like a great army advancing to battle. Rain-water begins to pour down from the eaves like a cataract. The perspiration stops. The clamminess of the ground is gone. All flies disappear to hide themselves and I can eat my rice. Ah, is this not happiness?

其一:夏七月,赤日停天,亦無風,亦無雲;前後庭赫然如洪爐,無一鳥敢來飛。汗出遍身,縱橫成渠。置飯於前,不可得喫。呼簟欲臥地上,則地濕如膏,蒼蠅又來緣頸附鼻,驅之不去。正莫可如何,忽然大黑車軸,疾澍澎湃之聲,如數百萬金鼓。簷溜浩於瀑布。身汗頓收,地燥如掃,蒼蠅盡去,飯便得吃。不亦快哉。2. A friend, one I have not seen for ten years, suddenly arrives at sunset. I open the door to receive him, and without asking whether he came by boat or by land, and without bidding him to sit on the bed or the couch, I go to the inner chamber and ask my wife: ‘Have you got a gallon of wine like Su Tungp’o’s wife?’ My wife gladly takes out her gold hairpin to sell it. I calculate it will last us three days. Ah, is this not happiness?

其二:十年別友,抵暮忽至。開門一揖畢,不及問其船來陸來,並不及命其坐床坐榻,便自疾趨入內,卑辭叩內子:「君豈有斗酒如東坡婦乎」內子欣然拔金簪相付。計之可作三日供也。不亦快哉。3. I am sitting alone in an empty room and I am just getting annoyed at a little mouse at the head of my bed, and wondering what that little rustling sound signifies – what article of mine he is biting or what volume of my books he is eating up. While I am in this state of mind and don’t know what to do, I suddenly see a ferocious-looking cat, wagging its tail and staring with its wide-open eyes, as if it were looking at something. I hold my breath and wait a moment, keeping perfectly still, and suddenly with a little sound the mouse disappears like a whiff of wind. Ah, is this not happiness?

其三:空齋獨坐,正思夜來床頭鼠耗可惱,不知其戛戛者是損我何器,嗤嗤者是裂我何書。中心回惑,其理莫措,忽見一狻貓,注目搖尾,似有所瞷。歛聲屏息,少復待之,則疾趨如風,唧然一聲。而此物竟去矣。不亦快哉。4. I have pulled out the haitang [crab-apple] and zijing [Chinese redbud] (flowering trees) in front of my studio, and have just planted ten or twenty green banana trees there. Ah, is this not happiness?

其四:於書齋前,拔去垂絲海棠紫荊等樹,多種芭蕉一二十本。不亦快哉。5. I am drinking with some romantic friends on a spring night and am just half intoxicated, finding it difficult to stop drinking and equally difficult to go on. An understanding boy servant at the side suddenly brings in a package of big fire-crackers, about a dozen in number, and I rise from the table and go and fire them off. The smell of sulphur assails my nostrils and enters my brain and I feel comfortable all over my body. Ah, is this not happiness?

其五:春夜與諸豪士快飲,至半醉,住本難住,進則難進。旁一解意童子,忽送大紙砲可十餘枚,便自起身出席,取火放之。硫磺之香,自鼻入腦,通身怡然。不亦快哉。6. I am walking in the street and see two poor rascals engaged in a hot argument of words with their faces flushed and their eyes staring with anger as if they were mortal enemies, and yet they still pretend to be ceremonious to each other, raising their arms and bending their waists in salute, and still using the most polished language of thou and thee and wherefore and is it not so? The flow of words is interminable. Suddenly there appears a big husky fellow swinging his arms and coming up to them, and with a shout tells them to disperse. Ah, is this not happiness?

其六:街行見兩措大執爭一理,既皆目裂頸赤,如不戴天,而又高拱手,低曲腰,滿口仍用者也之乎等字。其語剌剌,勢將連年不休。忽有壯夫掉臂行來,振威從中一喝而解。不亦快哉。7. To hear our children recite the classics so fluently, like the sound of water pouring from a vase. Ah, is this not happiness?

其七:子弟背誦書爛熟,如瓶中瀉水。不亦快哉。8. Having nothing to do after a meal I go to the shops and take a fancy to a little thing. After bargaining for some time, we still haggle about a small difference, but the shop-boy still refuses to sell it. Then I take out a little thing from my sleeve, which is worth about the same thing as the difference and throw it at the boy. The boy suddenly smiles and bows courteously saying, ‘Oh, you are too generous!’ Ah, is this not happiness?

其八:飯後無事,入市閒行,見有小物,戲復買之,買亦已成矣,所差者甚少,而市兒苦爭,必不相饒。便掏袖下一件,其輕重與前直相上下者,擲而與之。市兒忽改笑容,拱手連稱不敢。不亦快哉。9. I have nothing to do after a meal and try to go through the things in some old trunks. I see there are dozens of IOUs from people who owe my family money. Some of them are dead and some still living, but in any case there is no hope of their returning the money. Behind people’s backs I put them together in a pile and make a bonfire of them, and I look up to the sky and see the last trace of smoke disappear. Ah, is this not happiness?

其九:飯後無事,翻倒敝篋。則見新舊逋欠文契不下數十百通,其人或存或亡,總之無有還理。背人取火拉雜燒淨,仰看高天,蕭然無雲。不亦快哉。10. It is a summer’s day. I go bareheaded and barefooted, holding a parasol, to watch young people singing Soochow folksongs while treading the water-wheel. The water comes up over the wheel in a gushing torrent like molten silver or melting snow. Ah, is this not happiness?

其十:夏月科頭赤足,自持涼繖遮日,看壯夫唱吳歌,踏桔槔。水一時湥湧而上,譬如翻銀滾雪。不亦快哉。11. I wake up in the morning and seem to hear someone in the house sighing and saying that last night someone died. I immediately ask to find out who it is, and learn that it is the sharpest, most calculating fellow in town. Ah, is this not happiness? 其十一:朝眠初覺,似聞家人嘆息之聲,言某人夜來已死。急呼而訊之,正是一城中第一絕有心計人。不亦快哉。

12. I get up early on a summer morning and see people sawing a large bamboo pole under a mat-shed, to be used as a water-pipe. Ah, is this not happiness? 其十二:夏月早起,看人於松棚下,鋸大竹作筩用。不亦快哉。

13. It has been raining for a whole month and I lie in bed in the morning like one drunk or ill, refusing to get up. Suddenly I hear a chorus of birds announcing a clear day. Quickly I pull aside the curtain, push open a window and see the beautiful sun shining and glistening and the forest looks like it’s having a bath. Ah, is this not happiness?

其十三:重陰匝月,如醉如病,朝眠不起。忽聞眾鳥畢作弄晴之聲,急引手搴帷,推窗視之,日光晶熒,林木如洗。不亦快哉。14. At night I seem to hear someone thinking of me in the distance. The next day I go to call on him. I enter his door and look about his room and see that this person is sitting at his desk, facing south, reading a document. He sees me, nods quietly and pulls me by the sleeve to make me sit down, saying, ‘Since you are here, come and look at this.’ And we laugh and enjoy ourselves until the shadows on the walls have disappeared. He is feeling hungry himself and slowly asks me, ‘Are you hungry, too?’ Ah, is this not happiness?

其十四:夜來似聞某人素心,明日試往看之。入其門,窺其閨,見所謂某人,方據案面南看一文書。顧客入來,默然一揖,便拉袖命坐曰:「君既來,可亦試看此書。」相與歡笑,日影盡去。既已自饑;徐問客曰:「君亦饑耶。」不亦快哉。15. Without any serious intention of building a house of my own, I happened, nevertheless, to start building one because a little sum had unexpectedly come my way. From that day on, every morning and every night, I was told that I needed to buy timber and stone and tiles and bricks and mortar and nails. And I explored and exhausted every avenue of getting some money, all on account of this house, until I got sort of resigned to this state of things. One day, finally, the house is completed, the walls have been whitewashed and the floors swept clean; the paper windows have been pasted and scrolls and paintings are hung up on the walls. All the workmen have left, and my friends have arrived, sitting on different couches in order. Ah, is this not happiness?

其十五:本不欲造屋,偶得閒錢,試造一屋。自此日為始,需木,需石,需瓦,需磚,需灰,需釘,無晨無夕,不來聒於兩耳。乃至羅雀掘鼠,無非為屋校計,而又都不得屋住,既已安之如命矣。忽然一日屋竟落成,刷牆掃地;糊窗掛畫。一切匠作出門畢去,同人乃來分榻列坐。不亦快哉。16. I am drinking on a winter’s night, and suddenly note that the night has turned extremely cold. I push open the window and see that snowflakes come down the size of a palm and there are already three or four inches of snow on the ground. Ah, is this not happiness?

其十六:冬夜飲酒,轉復寒甚,推窗試看,雪大如手,已積三四寸矣。不亦快哉。17. To cut with a sharp knife a bright green water-melon on a big scarlet plate of a summer afternoon. Ah, is this not happiness?

其十七:夏日於朱紅盤中,自拔快刀,切綠沉西瓜。不亦快哉。18. I have long wanted to become a monk, but was worried because I would not be permitted to eat meat. If, then, I could be permitted to eat meat publicly, why, then I could heat a basin of hot water, and with the help of a sharper razor, shave my head clean in a summer month! Ah, is this not happiness?

其十八:久欲為比邱,苦不得公然喫肉。若許為比邱,又得公然喫肉,則夏月以熱湯快刀,淨割頭髮。不亦快哉。19. To keep three or four spots of eczema in a private part of my body and now and then to scald or bathe it with hot water behind closed doors. Ah, is this not happiness?

其十九:存得三四癩瘡於私處,時呼熱湯關門澡之。不亦快哉。20. To find accidentally a handwritten letter of some old friend in a trunk. Ah, is this not happiness?

其二十:篋中無意忽檢得故人手跡。不亦快哉。21. A poor scholar comes to borrow money from me, but is shy about mentioning the topic, and so he allows the conversation to drift along on other topics. I see his uncomfortable situation, pull him aside to a place where we are alone and ask him how much he needs. Then I go inside and give him the sum and after having done this, I ask him: ‘Must you go immediately to settle this matter or can you stay awhile and have a drink with me?’ Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿一:寒士來借銀,謂不可啟齒,於是唯唯亦說他事。我窺其苦意,拉向無人處,問所需多少。急趨入內,如數給與,然而問其必當速歸料理是事耶,為尚得少留共飲酒耶。不亦快哉。22. I am sitting in a small boat. There is a beautiful wind in our favour, but our boat has no sails. Suddenly there appears a big lorcha, coming along as fast as the wind. I try to hook on to the lorcha in the hope of catching on to it, and unexpectedly the hook does catch. Then I throw over a rope and we are towed along and I begin to sing the lines of Tu Fu: ‘The green makes me feel tender towards the peaks, and the red tells me there are oranges.’ And we break out in joyous laughter. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿二:坐小船,遇利風,苦不得張帆,一快其心。忽逢艑舸,疾行如風。試伸挽鉤,聊復挽之。不意挽之便著,因取纜纜向其尾,口中高吟老杜「青惜峰巒,共知橘柚」之句;極大笑樂。不亦快哉。23. I have long been looking for a house to share with a friend but have not been able to find a suitable one. Suddenly, someone brings news that there is a house somewhere, not too big, but with only about a dozen rooms, and that it faces a big river with beautiful green trees around. I ask this man to stay for supper, and after the supper we go over together to have a look, having no idea what the house is like. Entering the gate, I see that there is a large vacant lot, and I say to myself, ‘I shall not have to worry about the supply of vegetables and melons henceforth.’ Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿三:久欲覓別居與友人共住,而苦無善地。忽一人傳來云有屋不多,可十餘間,而門臨大河,嘉樹蔥然。便與此人共喫飯畢,試走看之,都未知屋如何。入門先見空地一片,大可六七畝許,異日瓜菜不足復慮。不亦快哉。24. A traveller returns home after a long journey, and he sees the old city gate and hears the women and children on both banks of the river talking in his own dialect. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿四:久客得歸,望見郭門,兩岸童婦,皆作故鄉之聲。不亦快哉。25. When a good piece of old porcelain is broken, you know there is no hope of repairing it. The more you turn it about and look at it, the more you are exasperated. I then hand it to the cook, and give orders that he shall never let that broken porcelain bowl come within my sight again. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿五:佳磁既損,必無完理。反覆多看,徒亂人意。因宣付廚人作雜器充用,永不更令到眼。不亦快哉。26. I am not a saint, and am therefore not without sin. In the night I did something wrong and I get up in the morning and feel extremely ill at ease about it. Suddenly I remember what is taught by Buddhism, that not to cover one’s sins is the same as repentance. So then I begin to tell my sin to the entire company around, whether they are strangers or my old friends. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿六:身非聖人,安能無過。夜來不覺私作一事,早起怦怦,實不自安。忽然想到佛家有布薩之法,不自覆藏,便成懺悔,因明對生熟眾客,快然自陳其失。不亦快哉。27. To watch someone writing big characters a foot high. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿七:看人作擘窠大書,不亦快哉。28. To open the window and let a wasp out from the room. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿八:推紙窗放蜂出去,不亦快哉。29. A magistrate orders the beating of the drum and calls it a day. Ah, is this not happiness?

其廿九:作縣官,每日打鼓退堂時,不亦快哉。30. To see someone’s kite-line broken. Ah, is this not happiness?

其三十:看人風箏斷,不亦快哉。31. To see a wild prairie fire. Ah, is this not happiness?

其卅一:看野燒,不亦快哉。32. To have just finished repaying all one’s debts. Ah, is this not happiness?

其卅二:還債畢,不亦快哉。33. To read the Story of Curly-Beard (who gave up his house to a pair of eloping lovers then disappeared). Ah, is this not happiness?

其卅三:讀虯髯客傳,不亦快哉。

— Lin Yutang, The Importance of Living, pp.135-140