In Watching China Watching (XII) — For Truly Great Men, Look to This Age Alone (China Heritage, 27 January 2018) — we noted the work done by Jeremy Taylor on wartime Chinese political personality cults. In particular, Taylor focussed on Chiang Kai-shek and Wang Jingwei, the founder in 1940 of a regime in the occupied Nationalist capital of Nanking that collaborated with the Japanese Empire. A hero in the late-Qing era, Wang would be one of the most controversial political figures of China’s Republic, As Taylor notes in his Republican Personality Cults in Wartime China:

Only in recent years has the Wang Jingwei personality cult has been taken seriously as a subject of academic inquiry. Like the RNG [Reorganized National Government, 1940-1945] itself, it has often been dismissed as nothing more than the detritus of Japanese militarism. The postwar dismantling of the Wang cult was made easier, ironically, by the RNG’s avoidance of widespread architectural, sculptural, or nomenclatural references to its leader, and this also contributed to its erasure from public memory in China.

And he observes that:

The now burgeoning literature on the cultural history of China under Japanese occupation has started to revisit the wartime cults of other leaders,such as the much-maligned Chinese collaborationist leader Wang Jingwei. Several scholars studying Wang have moved beyond the biographical approaches that epitomized earlier studies to explore the political culture Wang fostered through his ‘Re-organized National Government (RNG) of China,’ from 1940 to 1945,including a distinct personality cult that was created around Wang himself. David P. Barrett, in the most succinct summary of this cult, described how,

‘Innumerable editions of Wang’s articles and speeches were published; Ministry [of Propaganda] journalists followed Wang on his travels…, and major dates on the regime’s calendar were celebrated in the towns and cities with meetings and march-pasts lauding the leader. Photographs of Wang in the press far eclipsed those of his subordinates.’

Yet to be fully explored is the extent to which this wartime adulation of Wang represented not merely a part of collaborationist state building, but a conscious attempt to undermine, and set Wang apart from, his primary rival Chiang Kai-shek. Much has been written about their decades-long personal rivalry. … [A]ttempts to distance Wang from Chiang not only influenced how Wang was presented but also how those around him justified his leadership of a rival government.

— from Jeremy E. Taylor,

Republican Personality Cults in Wartime China:

contradistinction and collaboration,

Comparative Studies in Society and History,

57 (3), 2015: 665-693, at pp.692 and 666 respectively

Below the historian Craig Smith introduces Wang Jingwei’s Nanking regime. Smith has followed the burgeoning scholarship on Wang, including the recent work of the Beijing-based scholar Li Zhiyu 李志毓 (《驚弦:汪精衛的政治生涯》, 香港: 牛津大學出版社, 2014年), but he has noted that research has tended to focus on Wang’s political career and much remains to be done in regard to his writings, speeches and ideas.

This is the latest addition to China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking (included under The Republic: A City Murdered). For another recent work in the Annual, see William Sima’s translation of essays by the late-Ming littérateur Gu Qiyuan 顧起元 — Superfluous Words from a Nanking Salon 客座贅語 (China Heritage, 8 April 2018) — which is also collected in Wairarapa Readings.

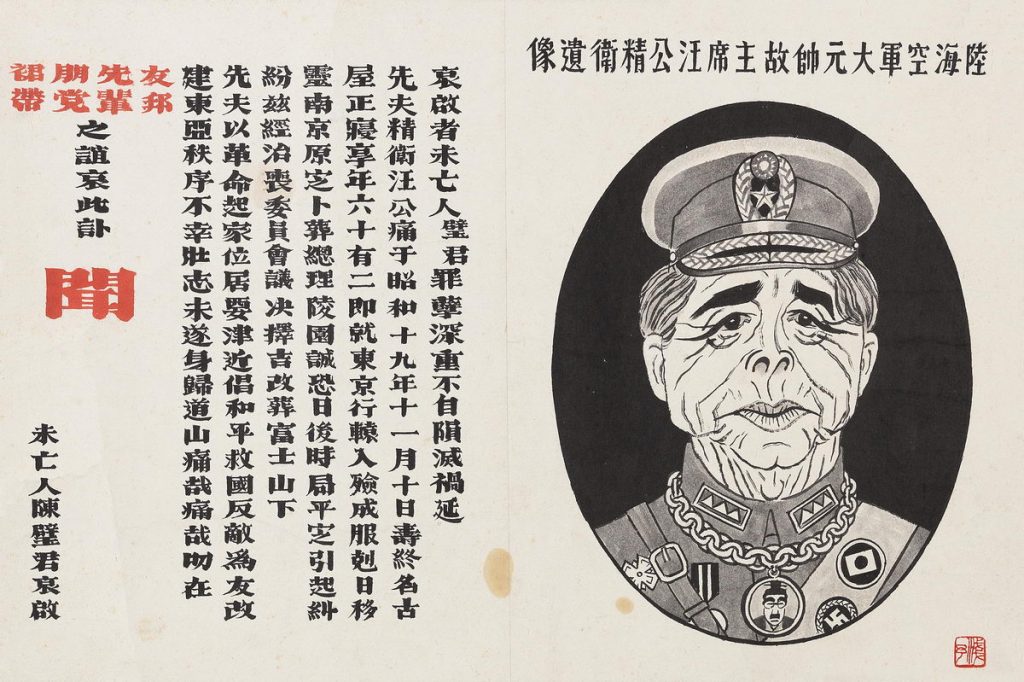

My thanks to William Sima, Associate Guest Editor of China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking, for his editorial and logistical contributions to this essay, and to Nick Stember for permission to use the image of Wang Jingwei by Ye Qianyu.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor

China Heritage Annual

15 May 2018

Further Reading:

- Frederick W. Mote, At War’s End: an academic GI in Nanking, China Heritage Annual 2017: Nanking, under ‘The Republic: A City Murdered’

- Timothy Brook, Hesitating before the Judgement of History, The Journal of Asian Studies, vol.71, no.1 (February 2012): 103–114

- Nick Stember, Saving the Nation Through Twisted Means: Zhang Yimou’s 張藝謀 Great Wall 《長城》, 27 September 2017

- Jeremy Taylor, From Traitor to Martyr: drawing lessons from the death and burial of Wang Jingwei, 1944, Journal of Chinese History, Issue 43 (2017): 1-22, published online, March 2018 (doi:10.1017/jch.2017.43)

Wang Jingwei’s

Reorganised National Government

中華民國維新政府

Craig A. Smith

From 1940 to 1945, wartime Nanking was home to one of the two Nationalist regimes. The Reorganised National Government of Wang Jingwei 汪精衛 played the role of a central government for the various regimes established by the Japanese military during its occupation of the Republic of China; it was established in opposition to the Nationalist government that had relocated to Chungking in Sichuan under Chiang Kai-shek. In the historiography both of the Republic of China on Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China this wartime period is seen as the low point in the history of Nanking, one during which a ‘puppet’ regime made use of Japanese military strength to establish sway over a large expanse of Chinese territory, albeit in name only. Wang Jingwei and the members of his regime are regarded as ‘traitors to the Chinese people’ 漢奸. However, Wang Jingwei, Chen Gongbo 陳公博, Zhou Fohai 周佛海 and many other elite Nationalist politicians, believed that their the peace movement they spearheaded was the only way to save China. Because of on the political lineage connecting them to Sun Yat-sen, the founder of the Republic of China in 1912, and to his Nationalist party they regarded theirs as a legitimate government.

Wang Jingwei had established his revolutionary credentials in the final days of the Qing dynasty when he joined Sun Yat-sen as a revolutionary intellectual who was willing to sacrifice himself for the nation. In 1910, he led a failed attempt to assassinate Prince Chun 醇親王 (載灃 1883-1951), the imperial regent and father of the emperor, Puyi 溥儀 [whose reign title was Xuantong 宣統]. Due to the chaos of the time, and because the government of the Republic of China established following the 1911 Revolution that ousted the Qing dynasty offered political prisoners amnesty, Wang avoided the death penalty and went on to hold various positions in the new government. Following Sun Yat-sen’s death in 1925, it was expected that Wang would succeed him as the political and ideological leader both of the Nationalist Party and of China. However, the party elite spilt between the scholar Wang and Chiang Kai-shek, whose position as the principal of the Whampoa Military Academy gave him control over the military. Despite a façade of unity, the divisions within the Nationalists were debilitating. Eventually, the sword bested the pen and Chiang led the Republic throughout what was known as the ‘Nanking Decade’, from 1927 to 1937, a period when the national government was based in the city of Nanking [see The Nanking Decade in China Heritage Annual 2017 — Ed.].

During the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945), Nanking was home to three different Chinese regimes. Chiang Kaishek’s Nationalist government famously abandoned the city in late 1937, immediately preceding the brutal invasion now known as the Rape of Nanking [see A City Murdered in China Heritage Annual 2017 — Ed.]. Even as Japanese troops occupied the city, the Imperial Japanese Army was planning to establish a local Chinese government, just as they had done in other areas of occupied China. In March 1938, Japanese commanders identified Liang Hongzhi 梁鴻志, a major figure in Duan Qirui’s 段祺瑞 Anhui Clique and a man who had enjoyed connections with Japan from his youth, as a suitable leader for what they dubbed the ‘Reformed Government of the Republic of China’ 中華民國維新政府. Liang’s government failed to garner popularity and it even struggled to gain support over the small area surrounding Nanking that it purportedly controlled. However, its existence set the stage for Wang Jingwei to establish a more significant regime in March 1940 which enjoyed a greater level of legitimacy.

The city of Nanking had been re-envisioned by the Nationalists as a capital city based upon the transcending legitimacy of Sun Yat-sen, the ‘Father of the Nation’ [see Rudolf G. Wagner, 1925-1928: Enshrining the Father of the Republic, China Heritage Annual 2017 — Ed]. Wang’s new government worked hard to establish its legitimacy based on the existing symbolism of the Nanking Decade. Unlike the so-called ‘hotel government’ of Liang Hongzhi — one temporarily operating out of hotels with many of its officials commuting from Shanghai — which struggled to rebuild a city devastated by warfare in 1937, Wang’s government immediately set up its administrations in the buildings of the previous governments that had just been refurbished by Liang. Wang occupied Chiang Kai-shek’s former Presidential Palace, the place where Sun Yat-sen had been proclaimed provisional president of the Republic of China on 1 January 1912. The building remained symbolically important and some hint of its lasting role even beyond the Japanese defeat is portrayed by Chen Yifei 陳逸飛 and Wei Jingshan 魏景山 in their 1977 painting of the 1949 occupation of the Presidential Palace by the Communist-led People’s Liberation Army.

Sun Yat-sen had instructed that Nanking should become the capital of the Republic, and Wang was well-equipped to play the role as political leader and to that end he built on his connection to Sun’s legacy and at every opportunity employed the figure of the Father of the Nation to shore up his legitimacy. In consultation with Zhou Fohai, Wang decided to continue using the name of the republic as well as its flag and its formal ideology. Although many patriots refused to cooperate with the occupying Japanese forces — they denounced Wang as a race traitor and relocated with Chiang’s government to the wartime republican capital of Chungking, many others from all walks of life joined his government or quietly acquiesced to its authority. There were also those who superficially paid due deference to Wang’s regime, while plotted against it from within.

The history of the collaborationist government, first led by Wang Jingwei and later by Chen Gongbo (1944-1945), was marked by violence and political assassinations. Even senior leaders in the regime, including Zhou Fohai, maintained contact with the national government in Chungking or the rebellious Communist Party organisation, ever ready to abandon their unsteady ship of state if the need arose. Double agents were commonplace and they often played important roles in the administration and propaganda organisations of the Nanking regime. In recent years, they have been a feature in historical representations of the period both in film and in literature including, for example, the popular film The Message 風聲 (2009). However, films set in collaborationist Nanking have not been as numerous or as well received as those concerning the same regime in wartime Shanghai. The latter include Lust, Caution 色、戒 (2007), adapted from the work of Eileen Chang 張愛玲, and the popular TV series The Disguiser 偽裝者 (2015).

Fictional representations of the period are limited by official perimeters set by China’s propagandists. Descendants of the wartime ‘traitors’, however, have joined forces with some academics in an attempts to offer a more nuanced understanding of this complicated period [link to wangjingwei.org]. Regardless, on the whole people both on Mainland China and on Taiwan remain outraged by Wang and his Reorganised National Government’s collaboration with Japan. From the moment it was established, both the Nationalists in Chungking and their Communist Party rivals denounced the Reorganised Government as ‘Wang Jingwei’s Phony Regime’ 汪偽政權. The term is still in official use.

Nationalist depictions of this period maintain a cultural power that allows ‘puppet government’ tropes to be trotted out to scapegoat opponents (public as well as political figures) when they take a stance contrary to that of the speaker. This is not unlike evocations of Nazi Germany which is familiar to Western political discourse. However, unlike the Nazi government in Germany, little remains of the Wang regime to remind people of its existence:

- Its flag was almost identical to that of the previous government;

- Wang’s ideology had little to set it apart from Sun Yat-sen’s;

- No major works projects were completed during its reign, and;

- The personality cult of Wang Jingwei-ism only left a mountain of propaganda texts and images, easily destroyed or buried in archives. Even the thousands of lapel pins bearing Wang’s image that officials compelled Nanking residents to wear at the height of the government’s New Citizens’ Movement remain rare collector’s items today.

Wang died in 1944 just as Japan’s war effort was reaching a precarious stage. Wang did not live to see the ignominious fate of his government, not in his last years was he aware of the gravity of the mistake he had made in supporting the Japanese. He could not have imagined the infamy that would subsequently attach to his name.

***

In death, as in life, Wang Jingwei tried to insinuate himself into the history of China and the symbolic landscape of Nanking. The Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum 中山陵 has been a site of quasi-religious significance since it was completed in 1929 [Link]. Wang frequently used the site as a backdrop for ceremonies of his own government. In 1942, he even mooted the possibility of being buried there himself. When he eventually died due to complications from wounds sustained in a 1939 assassination attempt, his followers planned to construct a large mausoleum for him next to that of Sun Yat-sen. However, wartime strictures made it an impossible enterprise; instead a temporary tomb was built on Plum Blossom Mountain near Sun’s mausoleum. When Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist army re-entered Nanking less than a year later, they immediately set about destroying the tomb. Nationalist hyperbole, however, obscures the actual details: revelling in the posthumous shaming of the most hated villain of the war, troops supposedly filled the site with 150 tonnes of explosives. Regardless of how much dynamite was used to obliterate the earthly remains of Wang, the sense of revulsion about his regime were unmistakable, the resulting devastation left no trace of a history many felt was best forgotten.

***