Today marks the eightieth anniversary of the Rape of Nanking, now generally known as the Nanking Massacre. In The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography the historian Joshua A. Fogel writes:

The Rape of Nanjing was one of the worst atrocities committed during World War II. On December 13, 1937, the Japanese army captured the city of Nanjing, then the capital of wartime China. According to the International Military Tribunal, during the ensuing massacre 20,000 Chinese men of military age were killed and approximately 20,000 cases of rape occurred; in all, the total number of people killed in and around the city of Nanjing was about 200,000.

Since 2014, the People’s Republic of China has marked this day with a national commemoration 南京大屠殺死難者國家公祭日.

***

The city of Nanking 南京, its history and culture, is the focus of the inaugural China Heritage Annual, which was launched in Shanghai in March 2017. Material is being gradually added to the annual. This commemoration of the horror of Nanking in 1937-1938 is part of our work on the city and we are very grateful to be able to present four works of Bapo 八破 art by Li Chengren 李成忎.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston recently mounted the first exhibition of Bapo art. The result of years of painstaking research and collecting by the art historian and curator Nancy Berliner China’s 8 Brokens: Puzzles of the Treasured Past was on exhibit at the museum from 17 June to 29 October 2017. We are grateful to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston for permission to reproduce these works and we are indebted to Nancy for her extraordinary work on Bapo art and for graciously agreeing to write a short introduction to Li Chengren’s work.

My thanks to John Minford for joining me in translating the doggerel verse of Li Chengren, inscribed in various calligraphic styles on the four scrolls.

***

Over the coming days, China Heritage will introduce other aspects of the Nanking Massacre, the historical debates surrounding it and recent official Chinese views of that harrowing event.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage,

13 December 2017

Li Chengren’s Piles of Brocade Ash

Nancy Berliner

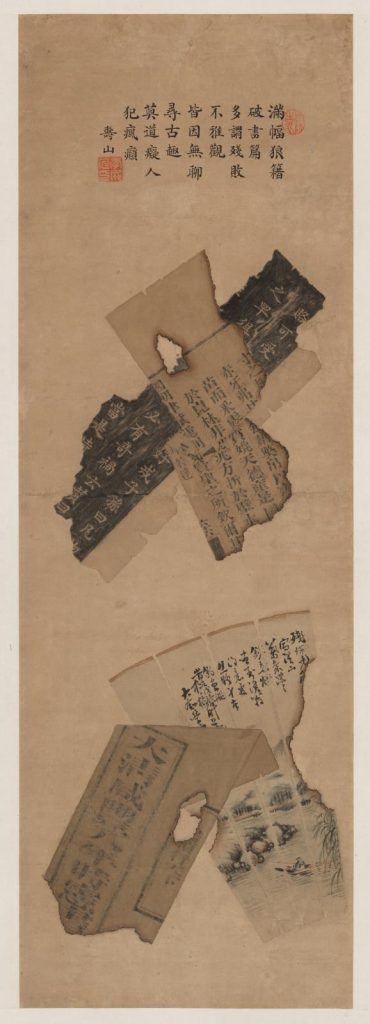

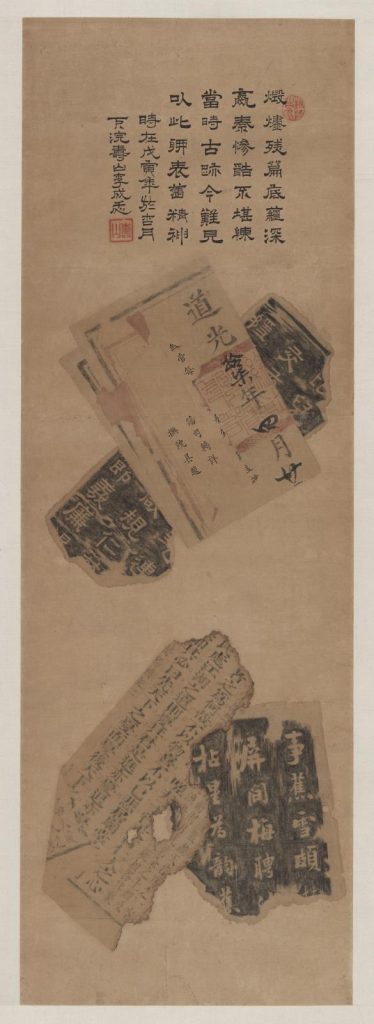

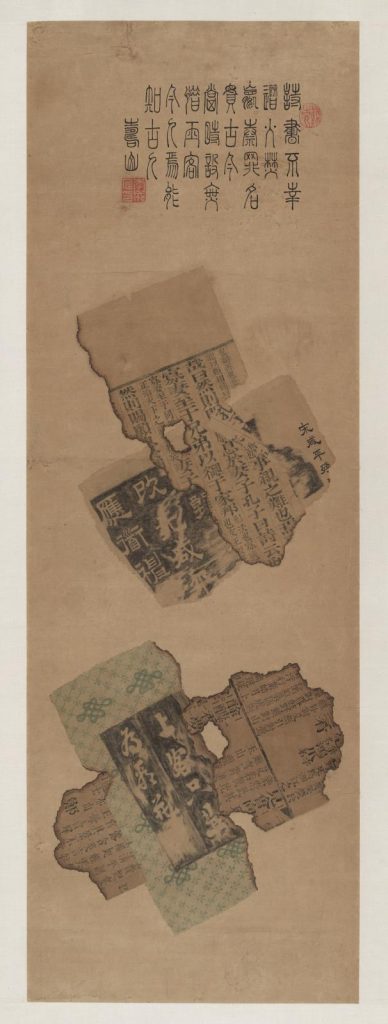

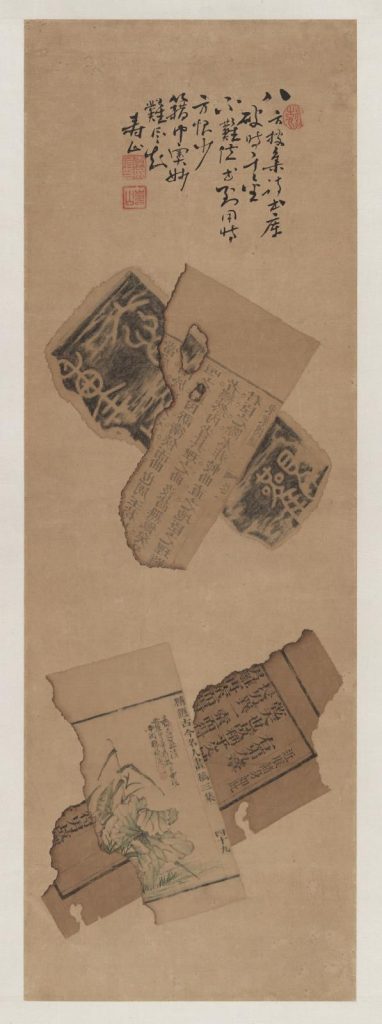

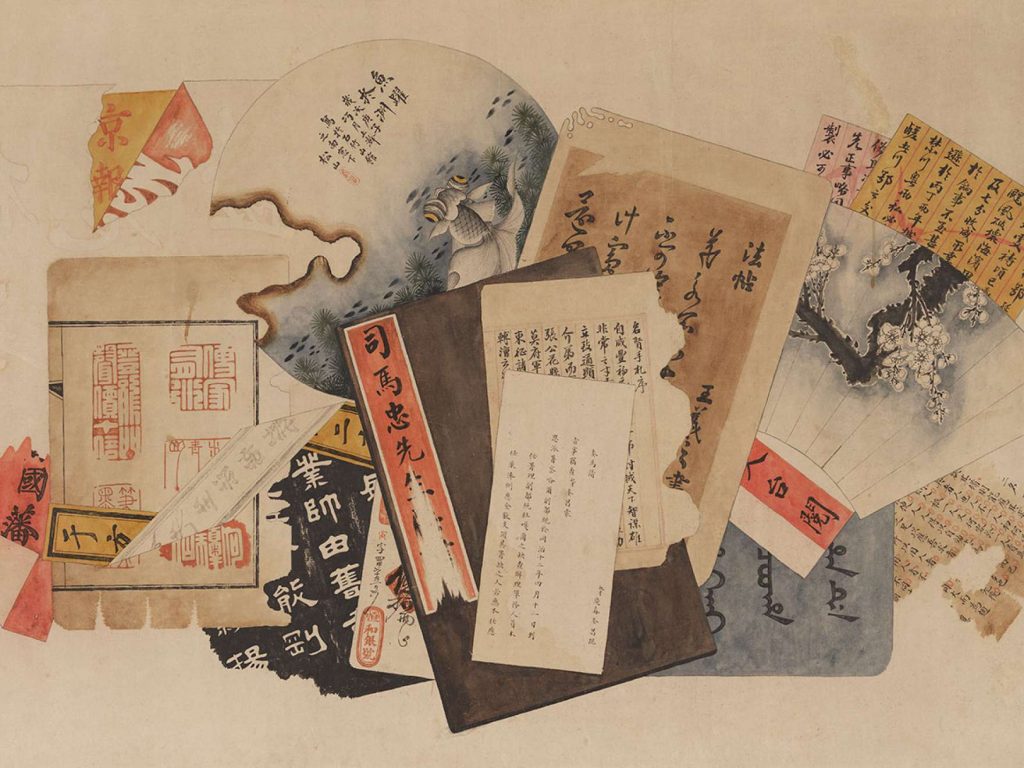

During the mid-nineteenth century, a surprising, new genre of painting emerged in small and large urban centers of China. Instead of landscapes, birds and flowers, figures or traditional narratives, a number of artists began depicting, with an exacting likeness, bricolages of texts, papers and calligraphy that appeared to have been randomly tossed on the painting’s surface. Known as bapo 八破, literally ‘eight brokens’ (in this context, eight means ‘many’), or jinhuidui 錦灰堆 (‘brocade ash piles’) — they are also variously known as 百碎圖、集破、集珍、什錦屏 — these paintings shared three characteristics:

- they were meticulously painted and not, despite appearances, a collage of papers pasted on the surface of the painting;

- they depict works, or the torn remains of works, of varying cultural significance in the Chinese tradition; and,

- the material represented is ravaged: torn, burnt, worm-eaten or discarded remains of works that are shown in varying stages of disintegration.

To the contemporary eye, bapo works seem strikingly modern. It is an art form that evolved out of a confluence of several Chinese artistic traditions including:

- epigraphy, a wide-spread obsession with ancient calligraphic works;

- still-life bogu 博古 (‘multitudes of antiquities’) painting;

- the practice of creating and displaying auspicious images; and,

- the embrace of the age-old poetic motives such as huaigu 懷古 (‘yearning for the past’) and sangluan 喪亂 (‘death and destruction’).

Poems composed to mourn war-ravaged cities or palaces are a common feature of bapo art. Just as common is the use of calligraphic rubbings and pages that appear haphazardly torn from a book of poems. The term ‘brocade ash piles’ jinhuidui itself originates with a Tang-dynasty verse in which the poet records his grief upon seeing the ashes of brocade in the ruins of the women’s quarter of a palace.

The artist Li Chengren 李成忎 (literary name, Shoushan 壽山) created the following series just weeks after the Nanking Massacre of 1937-1938. Although the calligraphic inscriptions on the paintings make no mention of Nanking, the artist does refer to the infamous despoliation of China’s first, and violent, dynasty, the Qin. He also includes calligraphic work from the Yuan dynasty, when China was ruled by Mongolian invaders. Are these quiet allusions to what had just happened in Nanking?

— Nancy Berliner

Wu Tung Curator of Chinese Art

Museum of Fine Arts Boston

10 December 2017

***

Further Reading:

- Nancy Berliner, ‘The “Eight Brokens”: Chinese Trompe-l’oeil Painting’, Orientations, vol.23, no.2 (February 1992): 61-70.

- 波士顿美术馆——迄今为止首个中国八破画的博物馆展览, 2 June 2017

- Nancy Berliner, Tour of China’s 8 Brokens Exhibition, YouTube, 18 July 2017

- Claire Barliant, Getting to grips with China’s bewildering bapo paintings, Apollo Magazine, 11 September 2017

- 中式“波普”:锦灰堆, 26 December 2010

A Fragmented World

in four scroll paintings

All four works are made in ink and colour on paper and they were presented to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston as an anonymous gift in memory of William W. Mellins. The dimensions of the works are 83.6 x 28.3 cm (23 15/16 x 11 1/8 in. — Ed.

***

顛倒橫斜任意鋪,

半頁仍存半頁無。

莫通幾幅殘缺處,

描來不易得相符。

***

滿幅狼藉破書篇

多謂殘敗不雅觀

皆因無聊尋古趣

莫道痴人犯瘋癲

壽山

***

A scroll of scattered fragments, broken books.

Others may say these scraps of mine lack grace.

I have sought the flavor of the past to fill a void.

Pray take not this folly of mine for madness.

Shoushan

嬴秦殘酷不堪陳

當時古跡今難見

以此聊表舊精神時在戊寅年於杏月上浣

壽山 李成忎

***

These singed fragments contain unfathomed depths.

Words can ne’er express the cruel tyranny of Qin.

True relics of ancient times are hard to find.

These shards I use to express the spirit of the past.

Dated the last days of the Apricot Month [second month of the lunar calendar], the Year Wuyin [1938], by Shoushan, Li Chengren

詩書不幸遭火焚

嬴秦罪名貫古今

當時設無惜玉客

今人焉能知古人

壽山

***

The books were committed to the flames, alas!

The Qin tyrant’s crime has resounded through the ages.

If it were not for the connoisseurs of the past,

How could we know today the men of yore?

Shoushan

破時重金亦難得

書至用時方恨少

籍中奧妙難盡書

壽山

***

From every quarter I add to my bounty of books.

Even damaged, they cost a fortune, but are worth every penny.

And yet whenever I need something, I find I have too few.

The mystery that lies within can never be fully expressed.

Shoushan

See also:

- Nancy Berliner, A Sylvan Symposium — ‘Artful Retreat: Garden Culture of the Qing Dynasty’, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 24 (December 2010);

- Geremie R. Barmé and Sang Ye 桑曄, A Note on the ‘Qianlong Garden’ 乾隆花園, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 24 (December 2010); and,

- Nancy Berliner, Not so Abstract: Re-considering the 1981 Exhibition of Masterpieces from the Museum of Fine Arts Boston, The China Story, 8 March 2013