Hong Kong Apostasy

Tsang Chi-ho (曾志豪, 1977-) is best known for his work with Ng Chi Sum (吳志森, 1958-) on Hong Kong Headliner, previously featured in our series on the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill Protests in Hong Kong. Tsang and Ng also produce a regular show on Youtube —《志森與志豪》— that consists of a dialogue on events unfolding in the city. Tsang also writes for Apple Daily, and the following is a translation of the column he published on 20 August 2019.

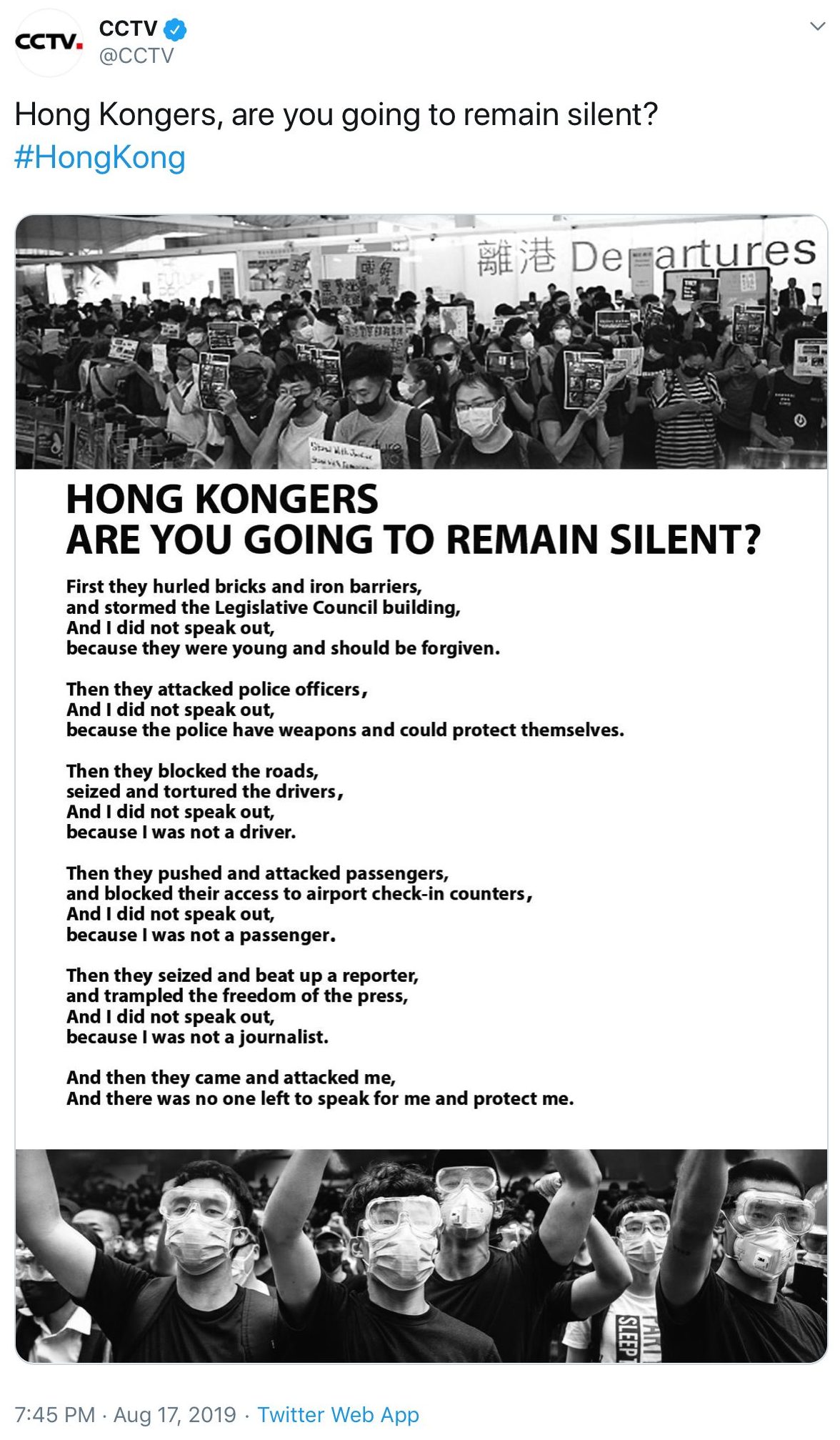

On the surface Tsang’s meditation on creeping authoritarianism in Hong Kong is slight, but for some readers it conveys a stark and urgent message; for me it has deep resonances. It also brought to mind a tweet by China Central TV in which a famous anti-Nazi poem by the Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller was twisted to serve a propaganda offensive aimed at portraying the Hong Kong protesters as violent thugs and borderline terrorists.

As The New York Times noted:

The People’s Daily version compares the persecution of Jews, socialists and trade unionists with protesters storming Hong Kong’s main legislative building, blocking roads and attacking reporters, including an accusation that demonstrators “trampled the freedom of the press.”

— Li Yuan, ‘China’s Soft-Power Failure:

Condemning Hong Kong’s Protests’

The New York Times, 20 August 2019

Note:

- For more on Niemöller and Hong Kong, see Lee Yee 李怡, ‘A Landscape Desolate and Bare’ 白茫茫大地真乾淨, China Heritage, 12 March 2018

- We would also observe with no little irony that, just as China’s propagandists were distorting Niemöller’s anti-Nazi message on behalf of a modern national-socialist state — one long derided by some independent Mainland thinkers as ‘fascist’ — the incumbent of the White House in Washington was employing anti-Semitic tropes to lambast his political enemies (see

***

During my teens in the late 1960s and early 1970s, and in particular when we studied modern German history in my last years of high school,[1] I often discussed the experiences that my grandmother and other family members had during Weimar and Nazi Germany (although my great uncle’s family relocated to London soon after the 1933 election that brought the National Socialist Party to national power, my immediate family remained in Cologne until the late 1930s. My grandfather was confined to an early Konzentrationslager, or concentration camp, and released only after the payment of a hefty ransom.)[2]

My uncle Hans, a conservative accountant, would regale me in magisterial fashion with stories about the economic and political incompetence of the Weimar Republic’s leaders and the evil genius of Nazi strategy and propaganda. My grandmother, who read constantly about the Holocaust, focussed rather on the details of everyday life — the undying friendships with ‘Aryan Germans’, as well as the cruel betrayals that accompanied the inexorable erosion of the family’s social position and the unfolding precariousness of their lives during the 1930s. Together we saw The Garden of the Finzi-Continis, first screened in Australia in 1971; we held hands and wept as ‘El Malei Rachamim’, the Hebrew lament for the dead, was recited at the end of the film. We also applauded the diversion of Cabaret, the burlesque elements of which were as a balm on wounds that, for my grandmother, remained searingly fresh.

***

After studying at Maoist universities in the mid 1970s — a personal enterprise that, given their history and despite their gentle warnings, my grandmother and her family found to be absolutely baffling — I worked for some years in Hong Kong, employed by Lee Yee, whose essays frequently feature in The Best China section of China Heritage. There, among other things, I slowly learned about what I came to think of as ‘authoritarian creep’ — that gradual stripping away of rights, and the concomitant psychological collapse of individuals as an intrusive political regime extended its sway over the lives, and hearts and minds, of those whom it ruled.

The translator Yang Yi (楊苡, 1919-) — my friend Yang Xianyi’s Nanking-based sister — was among those who told me about the transformative years of the early 1950s and a process parallel to that limned by Czesław Miłosz in The Captive Mind (1953). Yang Jiang’s 1988 novel Washing in Public 洗澡 (also known in English as Baptism), described the painful process of thought reform launched by the Communists in the educational world which we featured in ‘Ruling The Rivers & Mountains’, (Part I of our series ‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’, China Heritage, 8 August 2018-1 October 2018). It is that process that unfolded anew in Tibetan China following the protests of 2008, then in Xinjiang in recent years, just as it is gradually unfolding — although not without heroic resistance — in Hong Kong today.

***

For over fifty years, Hong Kong was a safe haven. As Lee Yee has noted:

‘Most Hong Kong people came to this place to escape tyranny on the Mainland.

[Note: ‘to escape tyranny on the Mainland’ is our transition of 避秦, literally, ‘to flee the Qin’. In his depiction of an idyllic world of peace and contentment, the fourth-century writer Tao Yuanming 陶淵明 said that people had come to the Peach Blossom Spring 桃花源 ‘to flee the Qin’, that is, they sought (and found) a refuge from the harsh rule of the Qin dynasty and its infamous First Emperor 秦始皇, a figure to whom Mao Zedong compared himself.]

‘Many just wanted a place where they could enjoy the ‘Freedom From Fear’. Over time, the British system with its traditions and protections instilled in Hong Kong people a belief that freedom and the rule of law were a natural state of affairs, something that was theirs to enjoy without them having to exert any particular effort. They had grown so accustomed to this environment that it seemed as natural as breathing the air around us; they did not give it a second thought. It simply was; it was a given; it wasn’t something for which you had to fight.’

— from Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Back in the Year —

Hong Kong 1984’, 31 July 2019

This, too, takes me back to the late 1970s when I worked for Lee Yee at The Seventies Monthly. It was a time when Hong Kong friends and colleagues were trepidatious about going to the Mainland. Nearly all of them had families or relatives who had suffered extreme deprivations over the previous three decades and among them the fear, the understanding of a systemic intimidation and the lingering terror was still palpable.

As a Caucasian travelling on a foreign passport, customs inspections at Shum Chun (and, after direct Hong Kong-Beijing flights were introduced, in the Chinese capital) by all rights would have been bothersome but not nerve-racking if not for the fact that, over the fifteen odd years during which I shuttled between the British Crown Colony and the Chinese capital I always had in my luggage illicit Hong Kong publications picked up for a host of Mainland friends. As a result, customs inspections were always stressful; I was frequently waylaid, questioned and had magazines and books much sought after in the north confiscated.

***

As the end of second decade of the twentieth century approaches for those of ‘a certain age’ it is sobering to feel with each passing day that one is, in many respects, ‘living into the past’. More disturbing by far, however, is it to know that friends in Hong Kong — that unique entrepôt of Global China — are, as Tsang Chi-ho notes balefully below, also growing ever closer to crossing the Rubicon of the Shum Chun River.

The persecution of individuals, groups, peoples is abhorrent. It forms a threnody through countless lives, including my own. Here I offer readers of ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’ Tsang Chi-ho’s essay in celebration of the remarkable city about which he writes, as a sobering reminder of things in its past, as an alarming addendum to present developments and as a caliginous prediction of things to come.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

21 August 2019

***

Notes:

- Our high-school German history textbook was a volume of translated source documents covering the decades from the end of World War I to the outbreak of World War II in Europe. The documents were primarily selected from government gazettes, newspaper reports and oral histories. They included official materials produced by the National Socialists — including the texts of laws the impact of which my grandmother spoke to me about — as well as virulent anti-Semitic ‘yellow journalism’ from such publications as Julius Streicher’s Der Stürmer and Völkisher Beobachter, the infamous bile-spewing Kampfblatt, or ‘fighting paper’, of the Nazis. I was learning German by myself and so, for a time, read some of this material in the original. These first-hand sources were supplemented by histories like William L. Shirer’s The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich and literary works including Joseph Heller’s Catch-22, both recommended to us by our modern history teacher. This early exposure to clashing documentary materials, oral histories and more rigorous scholarship would influence my subsequent writing, editing and translation work.

- My father’s family were German Jewish refugees, my mother’s were immigrants to Australia from England and Scotland. My brother and I were brought up as what I’d call ‘milquetoast Protestants’, although I declined to attend any more school Bible classes from about the age of eight. As for our refugee family, they were hardly any more religious for, although we all enjoyed both Jewish holidays and Christian festivities, during their long German sojourn the family had been ‘performative Lutherans’.

— The Editor

***

Related Material:

- Tsang Chi-ho and Ng Chi Sam, 《志森與志豪》, Youtube, 7 May 2019-

- ‘第五次民間記者會:「自由倒退至內地水平」 批警將遊行集會非法化 阻律師家屬接觸被捕者’, 《立場新聞》, 2019年8月19日

- Tsang Chi-ho 曾志豪 and Ng Chi Sam 吳志森 (RTHK), ‘Hong Kong Headliner — Kill Bill’, China Heritage, 14 July 2019

- Wong Wing-sum 黃泳欣, ‘Hong Kong Headliner Makes Headlines’, China Heritage, 24 July 2019

- Tsang Chi-ho and Ng Chi Sam, ‘返大陸手機點set先安全’, 《志森與志豪》, Youtube, 2019年8月20月

The Distance Between Totalitarianism and Us is Shrinking

我們和極權的距離

Tsang Chi-ho 曾志豪

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

— ‘The best thing about taking part in demonstrations at Admiralty is that you don’t need to be worried about being knifed by Triad gang members after dark.’

— ‘That’s so true! The Triads don’t dare come to the more tony districts like Admiralty and Central.’

— ‘Though, you still have to be afraid of being set upon on the way home from Admiralty. That’s what happened when people were attacked in Kwai Fong and Tsuen Wan.’

— ‘So it’s best to head home immediately after a demo; you won’t end up being knifed.’

[Note: The author is referring to a number of unprovoked stabbings in recent days. See, for example, , ’26-year-old woman in critical condition after knife attack at Hong Kong “Lennon Wall”‘, Hong Kong Press Press, 20 August 2019]

「在金鐘遊行最大好處,是夜晚不怕黑社會斬人。」

「對,金鐘中環高尚地區,黑社會都唔敢入嚟。」

「不過最怕係由金鐘返屋企嗰陣,俾人伏擊。葵芳荃灣嗰次就係咁。」

「所以遊行完都係早D返屋企,唔係又俾人斬。」

This is a recent exchange that I had with my wife. Can you tell what’s wrong here? There’s nothing our of the ordinary in any of the above statements; and that’s just it: the situation has been normalised.

Of course, we’re right that you won’t be got at by Triads in Admiralty or Central; but it’s also true that things can also go south on the way from a protest march. Nothing wrong with any of that, right? But isn’t there, really?

What’s wrong with this picture is that we’ve grown accustomed to the situation.

這是我和老婆的對話。發現甚麼問題嗎?句句都很普通,也很正常,金鐘中環的確沒有黑社會斬人啊,遊行完回家路上的確較容易出事啊。每一句都沒有說錯,有甚麼問題?問題就是,我們已經習慣甚至適應了這些問題。

In the normal course of events — at least, in the past — you would have felt safe when you took part in a demonstration no matter where they were taking place. Yet, here we are now, worried that we’ll be knifed if we venture into certain districts in Hong Kong.

本來不論在那一區遊行都應該很安全,為甚麼我們要擔心在其他區會被人斬呢?

Sure, during the protests of the 2014 Occupy Movement, things in Mong Kok did became pretty ropy, but at most people back then were only worried about troublemakers; it didn’t occur to anyone that they might actually be knifed!

In Hong Kong 2019, we’ve become ‘accustomed’ to the fact that there are parts of the city where it’s more than likely that you’ll be attacked by knife-wielding Triads. We’ve come to think of it as a new normal; it’s been regularised.

When parting, we’ve even taken to advising each other that we should be particularly careful on the way home. It’s because we now know there isn’t anyone out there who will come to our aid since there’s a new affinity between the police and the people who will most probably stab us, any of us.

2014年這麼大規模的佔領運動,旺角的確很雜,但大家也只是擔心有人踢場搞事,但不會想過「斬人」。2019年的香港,我們已經「適應」了在某些區,會被黑社會斬!我們習以為常,當成規矩。我們甚至提醒回家路上也會有危險!我們互相叮囑,因為知道無人可以幫自己,因為警察和斬人的關係太好了。

There are even warnings posted by people on Telegram like:

‘Friends — when you’re out there take extra care. Be aware that when you’re “heading home after school” the dogs might be let off the leash at every [MTR] station. Be particularly careful if you’re heading to Tsuen Wan, North Point and Yuen Long after a demonstration: gang members might be lying in wait.’

TG上甚至有人寫道「散水手足路上小心,各站可能有狗接放學。荃灣北角元朗回家特別注意放學安全小心黑社會。」

In the space of a few short months we have grown used to all of this. Formerly the safest city in Asia, Hong Kong has become its most dangerous!

短短幾個月,我們已經適應了,香港由亞洲最安全城市,變成最危險!

Here’s another exchange:

另一段對話。

— ‘Make sure you take a different phone when you are going through customs [inspection at the high-speed train terminal linking Hong Kong to Guangzhou at West Kowloon Station which is under the jurisdiction of the People’s Republic of China].

— ‘Yeah, I know. I’ve taken to backing up my WhatsApp and deleting everything on my phone beforehand.’

— ‘You can put all the photographs you’ve taken [of the events in Hong Kong] into a separate folder.’

— ‘You even need to make sure you don’t smirk when they’re carrying out their search, though.’

— ‘I’ve got business over there, so I make sure that I have pictures of cats and dogs on my phone to throw them off the scent.’

— ‘Just don’t take anything for granted; best take another phone with you entirely. It’ll be worse for you if they discover that you’ve got two phones on you.’

— ‘You’re not wrong …. Shhh, they’re coming.’

「過關嗰陣帶另一部電話。」

「我知,一早back-up WhatsApp再del晒。」

「相可以擺喺另一個folder。」

「佢搜嗰陣一定要鎮定笑笑口。」

「我上面做生意㗎,最多影兩張貓狗相頂住先。」

「唔好心存僥倖拎另一部電話過關,佢搜到2部電話仲麻煩。」

「係喎……佢地嚟啦。」

The Mainland customs people have taken to searching the luggage and checking the phones of inward bound travellers [from Hong Kong]. They’ve even detained some Hong Kong people as they go through customs.

大陸出入境都要搜查旅客背包以及手提電話,更有幾個香港人過關時直接被扣查。

The Extradition Bill hasn’t been passed, nor is it fifty years since 1997, yet here we are in Hong Kong already making necessary adjustments. It’s so bad that when someone is singled out at customs for a going-over their friends actually complain:

‘They know how sensitive things are right now. What the hell were they thinking deciding to going up there [to the Mainland]?’

And it is in these ways that we are demonstrating that totalitarianism is now closer to us than the Shum Chun River [that is, the Shenzhen River, the natural boundary between Hong Kong and the Chinese Mainland].

Hong Kong has changed and, gradually, we are accommodating ourselves to it.

未到送中,未過50年不變,但香港人已經變到這麼配合和適應,甚至有人被扣查,朋友都忍不住埋怨「明知呢輪敏感做乜返上去」。這句話已經說明,我們和極權的距離已經短過深圳河,香港變了,而我們,竟也慢慢能適應。

***

Source:

- 曾志豪, ‘我們和極權的距離’, 《蘋果日報》, 2019年8月20日