The Tower of Reading

‘No one understands me!’ 莫我知也夫。

Confucius’s famous — and, truth be told, somewhat smug — lament is recorded in The Analects, the influential collection of observations, brief statements, short dialogues and anecdotes attributed to him.

When The Master, as Confucius is known, was asked what he meant by this exclamation, his reply was famously gnomic:

I do not accuse Heaven, nor do I blame men; here below I am learning, and there above I am being heard. If I am understood, it must be by Heaven. 不怨天,不尤人。下學而上達。知我者,其天乎。

Elsewhere, The Master summed up his lifelong pursuit of learning and influence in the following way:

At fifteen, I set my mind upon learning. At thirty, I took my stand. At forty, I had no doubts. At fifty, I knew the will of Heaven. At sixty, my ear was attuned. At seventy, I follow all the desires of my heart without breaking any rule. 吾十有五而志於學,三十而立,四十而不惑,五十而知天命,六十而耳順,七十而從心所欲不踰矩。— trans. Simon Leys.

Students, in or of China, are familiar with this famous autobiographical snapshot, just as they are with Sima Qian’s account of his work and his life 太史公自序, Tao Yuanming’s self-description as Mr Five Willows 五柳先生, as well as Liu Yuxi’s sketch of his humble dwelling 陋室銘. Huaisu, the Tang-era monk, is also renowned for the exuberant calligraphy of the account of his life 自叙帖.

A personal favourite from the late tradition is Pu Songling’s introduction 自志 to his collected ‘strange tales’. It concludes with a message from ‘the dark frontier’:

Of my flickering lamp,

Fashioning my tales

At this ice-cold table,

Vainly piecing together my sequel

To The Infernal Regions.

I drink to propel my pen,

But succeed only in venting

My spleen,

My lonely anguish.

Is it not a sad thing,

To find expression thus?

Alas! I am but

A bird

Trembling at the winter frost,

Vainly seeking shelter in the tree;

An insect

Crying at the autumn moon,

Feebly hugging the door for warmth.

Those who know me

Are in the green grove,

They are

At the dark frontier.

Written on a spring day,

in the eighteenth year

of the Kangxi reign [1679].

獨是子夜熒熒,

燈昏欲蕊;

蕭齋瑟瑟,

案冷疑冰。

集腋為裘,

妄續《幽冥》之錄;

浮白載筆,

僅成《孤憤》之書。

寄託如此,

亦足悲矣。

嗟乎。

驚霜寒雀,

抱樹無溫;

吊月秋蟲,

偎闌自熱。

知我者,

其在青林黑塞間乎。

康熙己未春日

***

Autobiographical works proliferated from the late-nineteenth century. They include Autobiography at Forty 四十自述 by the moderate Republican reformer Hu Shih and the hubristic poem ‘Snow’ 雪 by his nemesis, Mao Zedong.

From the early 1940s, as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Mao instituted a regime of compulsory self-revelation in the form of personal narratives 生平闡述, confessions 檢討/檢查, self-criticisms 自我批評 and political accounting 交代. Even after eighty years the Party continues to demand that its members ‘hand over their hearts’ 交心, still often in written (or digital) form.

***

We mark the end of the year 2023 with a more light-hearted work, a self-description by Qiao Ji (喬吉, 1280-1345), introduced, translated and annotated by Brendan O’Kane whose own self-description reads:

Scrutable Occidental, erstwhile 北漂, quondam translator, congenital Philadelphian, 明清小說 enjoyer. (See also his account on Bluesky.)

We are grateful to Brendan for permission to reprint ‘Qiao Ji Explains Himself’ from Stories from a Burning House and are delighted to include Brendan’s lighthearted yet learned essay — no dark frontier here — in our series The Tower of Reading. It is a model of artful rather than artificial translation.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 December 2023

***

Qiao Ji Explains Himself

Brendan O’Kane

28 December 2023

A demimonde valedictorian, laughingly playing Imperial Historian

I mentioned that sanqu was a verse form that the nerds never got a chance to ruin. Behind this stroke of good luck for me lies an awful lot of bad luck for everyone alive at the time, from the Mongol conquest of the Song dynasty (bummer!) to the kicking-away of what Ping-ti Ho called the “ladder of success” — the notionally meritocratic system of examinations that had allowed literate men from good families to make a stable living in the civil service:

不讀書最高,不識字最好,

不曉事倒有人誇俏。

老天不肯辨清濁,好和歹沒條道。

善的人欺,貧的人笑,讀書人都累倒。

立身則小學,修身則大學,

智和能都不及鴨青鈔。There are no readers at the top —

Illiterate? You’ll benefit. And praise

Is the prize for idiocy nowadays.

For Heaven won’t discriminate

Between the low-down and the great,

And men have never understood

The difference between bad and good.So mock the poor. Defraud the kind.

Watch anyone with learning fall behind.

Or practice your calligraphy

and study your epigraphy: You’ll find

The learned and the competent

Are worth less than a copper cent.

Anonymous¹

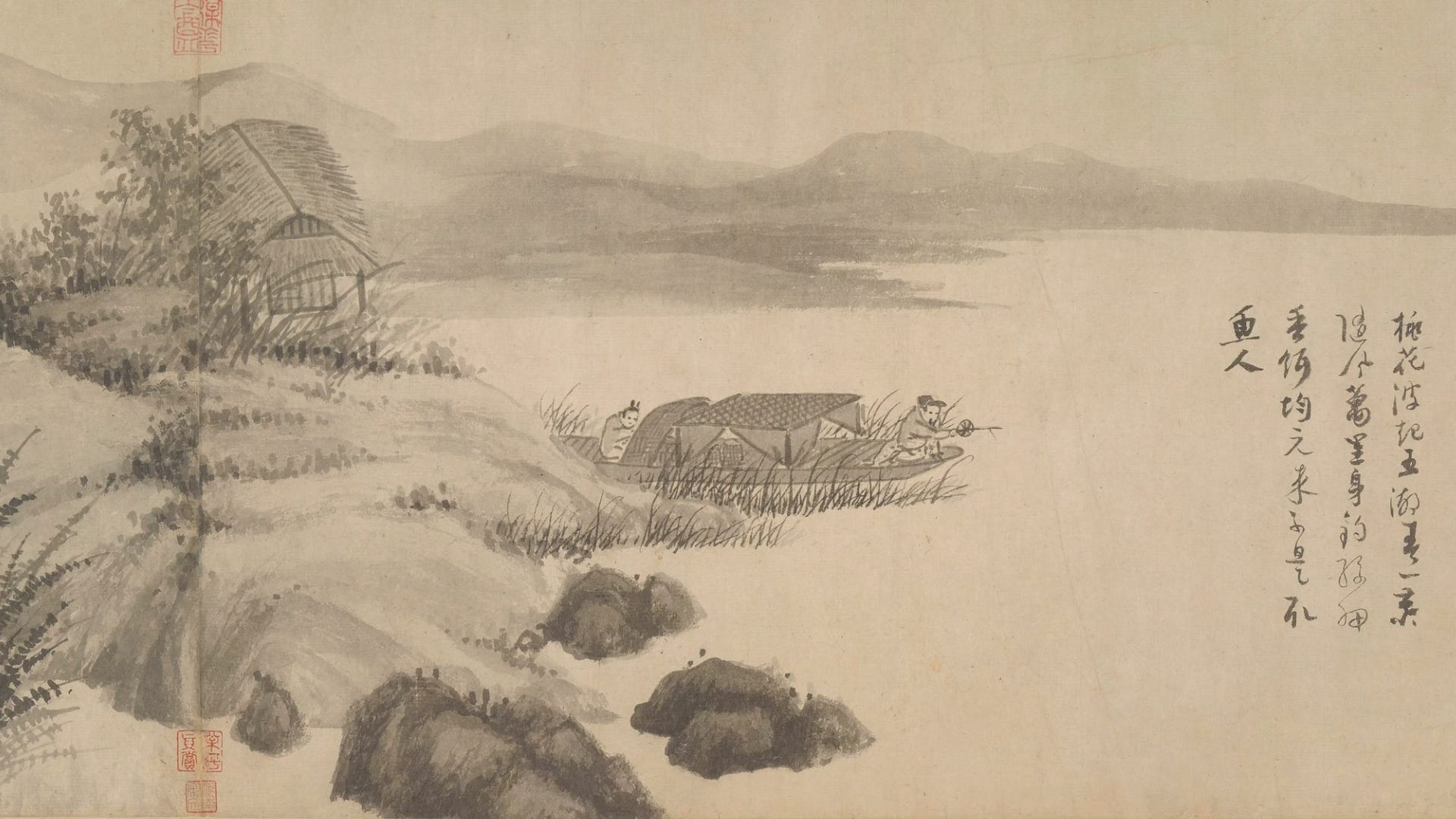

But having nothing left to lose is just another way of describing freedom, as Kris Kristofferson said if you apply the transitive property of equality. Here’s the poet and playwright Qiao Ji 喬吉 (1280-1345) to close out 2023 with one of my all-time favorite articulations of the joy and goodwill universally felt by all humans, in all places and times, upon leaving a PhD program:

自述

不占龍頭選,不入名賢傳。

時時酒聖,處處詩禪,

煙霞狀元,江湖醉仙,

笑談便是編修院。

留連,

批風抹月四十年。Explaining Myself

I didn’t ace the Examination

or make it to the Final Ten.

I won’t be up for celebration

in Biographies of Worthy Men.

But I play the Sage of Drinking now and then —

and, here and there, find inspiration

for poetic Zen.I’m a demimonde valedictorian,

transcendently boozy

and far past reformation,

Laughingly playing Imperial Historian

as I judge the world

for praise or condemnation.I roam,

My friends and peers —

Jotting comments on the wind my only occupation,

footnoting the moonlight for my poems

these forty years.

|

That’s it; that’s the poem I wanted to share, and well-adjusted people can stop reading here. But I started talking about sanqu [散曲] in the first place partly because I wanted to talk about translation — some people have expressed an interest in hearing more about my translation process; consider your bluff called.

I thought I’d add some notes on this and two other English versions by James Crump and Stephen Owen, both as a way of talking about craft and by way of pointing out where I’m playing fair and where I’m cheating a bit and why. The idea isn’t to knock anyone else’s translation or brag about my own (I do think mine is better, obviously; why would I have posted it if I didn’t?) but rather to pull back the curtain to reveal some of how the sausage is made where the rubber meets the road. It tends to be as messy as that sentence.

If you look at the original poem, even without knowing Chinese, you can see it’s expanded considerably on the journey. Some of this is just down to the standard 字-to-character exchange rate — written Chinese is compact — but note how 9 lines of Chinese turn into 18 lines of English, starting when I turn each of the opening two lines into a couplet. This gives me a bit of breathing room to work in, and also leaves me space for clarifying or amplifying things that require it.

Take the first two lines, 不占龍頭選,不入名賢傳: a character-by-character gloss would be “[I] don’t occupy [the] Dragon-Head List; [I] won’t [be] enter[ed in the] Famous Worthies’ Biographies.” But anyone reading this when it was written would have recognized “Dragon-Head” as referring to the top-scoring candidates on the examinations; hence “ace the Examination” and “the Final Ten.” The second line is pretty straightforward, though “up for celebration” is my probably unnecessary expansion on what it meant to have one’s name and biography added to such a list. (I also owe Stephen Owen for the title, as will be obvious in a moment.)

I’ve expanded even more in the central couplet, 煙霞狀元,江湖醉仙,笑談便是編修院, but readers of Chinese will note that everything from “demimonde valedictorian” to “laughingly playing Imperial Historian” is basically a straightforward-verging-on-literal translation.² “Judge the world for praise or condemnation” isn’t in the original, except on a closer look it sort of is, insofar as that’s the relevant part of the historian’s responsibilities — i.e., what “playing Imperial Historian” actually means.³

The last verse is where I’m really cheating. Before I explain how and why, let’s pop over and see what Crump and Owen are doing. Both are good. Here’s Crump:

State honor rolls will lack my name

As do biographies for men of fame.

I have from time to time

Found sagehood in a cup of wine;

Now and then,

Some verse of mine

Has contained one brilliant line

Enlightening as zen.

With the Drunken Sage of Lake and Stream

And the Graduate of Sunset Sky

We’ve laughed and talked and ascertained

Just whom the state should dignify.

Loitering,

For two score years here I’ve remained—

In the perfect place to criticize

The coolness of a breeze at noon,

Or add poetic luster to an evening’s moon.⁴

And Owen, whose version I saw first:

I didn’t graduate in the top ten,

I’m not in “The Lives of Famous Men.”

Now and then I’m Sage of Beer,

I find zen of poetry everywhere.

A cloud and mist valedictorian,

the drunken immortal of lakes and the river.

In conversation, witty and clever —

my own kind of Royal Historian.

After forty years I still endure,

of life’s finer pleasures,

connoisseur.

Crump reads the “Drunken Sage of Lake and Stream” and “Graduate of Sunset Sky” as referring to Qiao Ji’s friends rather than the poet himself. I don’t think this is a good reading, but it’s not an indefensible one, and I like his amplification (“ascertained…”) of “Imperial Historian.” Owen reads 處處 as “everywhere” rather than “here and there,” but that’s a judgment call, as is “beer” versus “wine” for 酒. I think he misses the point with “Royal Historian,” or at least doesn’t make it as clear to his readers as he could, but on the whole I’d say all three versions are more or less in agreement so far.

The last two lines are where it all starts to break down.

Crump and I both expand, while Owen keeps to two lines, but the differences start with 留連 liúlián, a word for which the Hanyu da cidian includes the definitions “to be at a standstill,” “to wander,” “to delay,” “to linger (because unwilling to leave),” “to continue or drag out,” “to urge a guest to stay,” and “durian, if you write it wrong.”

“Untranslatable” is not a good word; it’s for lazy translators and laypeople who have never really thought about language.⁵ But there are words — way more than you’d think — for which a “literal translation” is a logical impossibility. The translator can’t shirk their responsibility here: there is no way to translate this word without making an interpretive choice. (Try to imagine any translator seriously entertaining the possibility of “durian.”)

Next: 批風抹月 pīfēng-mǒyuè, “versifying in praise of nature” or something along those lines. Crump and I both overtranslate by reading it more literally: “commentating on the wind and annotating the moon.” Owen glosses this as “of life’s finer pleasures, / connoisseur,” retaining the connotations of judgment and taste but jettisoning the image.

And finally there’s 四十年 sìshí nián, “forty years,” which means “forty years.” This was the hardest line to translate.

***

I won’t lie, I was feeling pretty pleased with myself about the alternating -ation / -en rhymes at the beginning of my first draft. I liked the rhythm; I liked the jokiness;⁶ it felt like a good reflection of the brashness of the original.

The only problem was that I couldn’t sustain it through the end of the poem. Every line in Qiao’s poem rhymes with nián, “years.” The whole thing is building up to that final flourish (“… for forty years!”) and the translation really has to end the same way. And I just couldn’t make it work: I kept having to fall back on more or less the same things that Owen and Crump fall back on in their translations, which forced the poem into an anticlimax.⁷ I could switch up the rhyme in the final couplet, but then I’d lose the connection to the rest of the poem.

So I cheated and I hoped you wouldn’t notice.

Yeah, I can try to defend “My friends and peers,” I guess; Qiao was writing for an audience of his whatevers. But no, it’s a cheap trick, a shim, a bit of folded paper jammed under the wobbly table leg of the translation. If it wasn’t offensively obvious to you before, it will be now. How I hate it!

And then there’s my overtranslation of 批風抹月 pīfēng-mǒyuè. It’s about 20% too cute for my liking. I like it a lot more than any alternative I can think of, and I love the image of “jotting comments on the wind and footnoting the moonlight for a poem” — but even though those images are in there, I can’t convince myself that they would have been quite so front-of-mind for Qiao and his readers: (Many years ago in Barcelona, a friend of my father’s was absolutely in love with the English expression “there’s no use crying over spilt milk.” When’s the last time you thought about that one?)

“Roam” for 留連 liúlián just feels like obviously the right choice.⁸ Come on. The persona from the central couplet doesn’t linger. “Loiter,” maybe, but loitering with intent. I dunno: I think reading it in the sense of 流離 liúlí, “wandering” fits better with the rest of the poem, but I can’t say for sure that reading it that way isn’t at least partly motivated by wanting a rhyme for “poem” further down.

Either way, Owen’s not as good here. We might grant “endure” for purposes of rhyming with “connoisseur” — which has a real charm to it — but I don’t think there’s any way of getting anything better than “hang around” out of liúlián. And while we’re at it, I don’t think Qiao — or the persona he’s inhabiting here — could afford “life’s finer pleasures.” (The fine pleasures of the breeze and the moon are free, of course, but they’re nowhere to be found in this translation.)

I think Crump is trying to split the difference with “loitering.” (“Remained” is there to rhyme with “ascertained,” I think.) It’s not bad, but I don’t quite buy it. Part of our disagreement might be down to Crump’s reading of 煙霞狀元,江湖醉仙 as referring to the Qiao-persona’s friends, “the Drunken Sage of Lake and Stream and the Graduate of Sunset Sky” — maybe the idea is that he’s hanging out and kicking it with his homies. I think he’s wrong there, but he’s wrong because he knows too much: in a footnote, he notes that the Quan Yuan sanqu also contains a very similar Qiao Ji poem in which these might plausibly be nicknames:

溪友留連,笑談便是編修院,誰貴誰賢,

不應舉江湖狀元,不思凡蓑笠神仙。(By the creek, I liúlián with my friends, / Laughingly playing Imperial Historian: / Who was noble? Who was worthy? / Underworld valedictorian[s?] who never sat the Examinations, / Transcendent[s?] in rush cape and straw hat who care nothing for the world.)

I don’t think they’re nicknames.

Other than that, I like Crump’s rendering: we hit upon the same idea for handling 批風抹月 pīfēng-mǒyuè, which is always reassuring. I’m a little surprised that he didn’t try the same cheat I did for “forty years,” since it’s a trick he uses in some of his other translations, but then again it didn’t occur to me until a pretty advanced draft of this translation had matured on the shelf for about 18 months. (Shout-out to Matt T.!)

***

All in all, I’d give the latest draft a B+: good enough to show in public; good enough to dissect; good enough, all things considered, for 2023. But I think that’s enough sausage-making for one post — and enough poetry for one year.

Happy New Year, all — here’s hoping for a better 2024.

***

Notes:

1. There’s another poem in the Quan Yuan sanqu that shares the same opening to each line, which I won’t attempt to reflect in translation. Here’s the start:

不讀書有權,不識字有錢,

不曉事倒有人誇薦。The powerful don’t read,

The illiterate are loaded,

Fuck up and you’ll get promoted.

When you see a doublet like this, what you’re looking at is an invitation, received 900 years too late, to a boozy party where friends shouted lines out over cups of wine for other friends to complete, rhyme with, or outdo. I translate to keep the party going.

2. 江湖 jiānghú (“rivers and lakes” > “demimonde”) is hard to translate and you will have to come up with something different and contextually acceptable every single time. There are no good, usable all-purpose translations, though “The Game,” as used by e.g. the characters in The Wire, would be pretty close. Here I’m going with “far past reformation” and not even feeling a little bit bad about it.

Both Owen and Crump render jiānghú and its counterpart 煙霞 yānxiá literally, though for different reasons. I’m reading jiānghú in its idiomatic sense, and doing the same for yānxiá, which means both “mist and rosy clouds” and, idiomatically, the worldlier parts of the world. The latter seems a lot more plausible to me in context, especially in connection with jiānghú, but I could be wrong.

3. n.b.: If anyone feels like singing the middle verse to the bit about “go[ing] directly to your respective Valhallas” from Tom Lehrer’s “We Will All Go Together When We Go,” I cannot stop you.

4. Crump, Song-Poems from Xanadu, 93.

5. “‘Relationships’ is an untranslatable word meaning guanx—” ——BZZZZZT. You translated it!

6. As John Hollander said:

A serious effect is often killable

By rhyming with too much more than one syllable.(Rhyme’s Reason, 24.)

7. “…is all I’ve had by way of occupation” was one attempt. We don’t have to talk about it. At least “peregrination” didn’t last long enough for me to write it down.

8. The Hanyu da cidian also gives a definition of “dissolution” (指沉醉逸樂之事). This could be and probably is a gap in my knowledge, but that one feels a lot like one of the HDC’s occasional “there is exactly one case of an important person using the word this way, so we’d better include it as one of the top definitions and only give a single example” definitions. It’d be pretty tempting otherwise, though.

***

Source:

- Brendan O’Kane, ‘Qiao Ji Explains Himself’, Stories from a Burning House, 28 December 2023

***