During the Six Dynasties [六朝, 220-589 CE] a new prose genre, the zhiguai 志怪 tale [or ‘tales of the strange and supernatural’], emerged clearly from the mass of occasional writings of China’s literati. Stimulated by the intellectual ferment of the times, chronic political instability, and a great tide of foreign influences, the growth in the writing of these tales was explosive.

— Kenneth DeWoskin

Below we have selected stories from three of the most famous collections of ‘weird accounts’:

- Searching for Spirits 搜神記

- Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異

- Jottings from the Thatch Hut for Examining Minutiae 閱微草堂筆記

Searching for Spirits 搜神記

In Search of Spirits 搜神記 by Gan Bao (乾寶, fl.315CE), historian in the court of the Eastern Jin Emperor Yuan… is a reasonably well preserved work. According to his biography in the Jin History, Gan Bao was converted to a belief in spirits when he witnessed the miraculous rebirth of his brother and the miraculous preservation of his father’s favourite maid, ten years after she was interred alive at the father’s funeral. In his own preface, Gan Bao indeed asserts that he undertook the writing of the book to document the existence of spirits and ghosts.

— Kenneth DeWoskin

Song Dingbo Sells a Ghost 宋定伯捉鬼

When Song Dingbo of Nanyang [Henan province] was a young man he was once walking at night, when he ran into a ghost. He asked, ‘Who are you?’ The ghost replied, ‘I am a ghost.’ 南陽宋定伯,年少時,夜行逢鬼。問曰:誰?鬼曰:鬼也。

Then the ghost asked, ‘Who are you?’ Dingbo lied and said, ‘I am also a ghost.’ The ghost asked him, ‘Where are you off to?’ Dingbo replied, ‘I am going to the town of Yuan.’ ‘I am also going to Yuan,’ said the ghost, and he walked along with Dingbo. 鬼曰:汝復誰?定伯誑之,言:我亦鬼。鬼問:欲至何所?答曰:欲至宛市。鬼言:我亦欲至宛市。遂行數里。

After several miles, the ghost complained, ‘Walking by foot is just too slow. What do you say we run along and take turns carrying each other?’ ‘Great,’ replied Dingbo. The ghost was first to carry Dingbo, but after several more miles he noted, ‘You are very heavy! You aren’t a ghost.’ 鬼言:步行太亟,可共遞相擔(共遞相擔:兩人交替地背著。定伯曰:大善。鬼便先擔定伯數里。鬼言:卿太重,將非鬼也?

Dingbo replied, ‘I’m a new ghost, so my body is still heavy.’ Dingbo then picked up the new ghost and found him to be almost weightless. They went back and forth like this several times, when Dingbo asked, ‘Being a new ghost, I am not clear what I should fear and avoid.’ The ghost told him, ‘The only thing we don’t like is human spittle.’ 定伯言:我新鬼,故身重耳。定伯因復擔鬼,鬼略無重。如是再三。定伯復言:我新鬼,不知鬼悉何所畏忌?鬼答言:惟不喜人唾。

So they walked along together some more. Coming to a water crossing, Dingbo asked the ghost to go first. He listened, and Lo and behold, there was not a sound. When Dingbo himself crossed, there were all sorts of gurgling noises. The ghost questioned him again, ‘How is it that you make noises?’ ‘I just died, and I am not practiced in crossing waters. Don’t distrust me!’ 於是共行。道遇水,定伯令鬼先渡,聽之,瞭然無聲音。定伯自渡,漕漼作聲。鬼復言:何以作聲?定伯曰:新鬼,不習渡水故耳,勿怪吾也。

When they were about to reach Yuan city, Dingbo again picked up the ghost. Once he had him on his shoulders, Dingbo held on tightly. The ghost yelped and yelped to be let down, but Dingbo paid no attention. When they reached the middle of the city he finally put the ghost down, and it transformed into a goat. So Dingbo sold it, but fearing further transformations, he spat on it. He got fifteen hundred cash and left. At that time, a local magnate named Shi Chong was wont to say, ‘Dingbo sold a ghost and earned fifteen hundred cash!’ 行欲至宛市,定伯便擔鬼著肩上,急執之。鬼大呼,聲咋咋然,索下,不復聽之。徑至宛市中。下著地,化為一羊,便賣之。恐其變化,唾之。得錢千五百,乃去。於時石崇言:定伯賣鬼,得錢千五百文。

— translated by Kenneth DeWoskin,

from John Minford and Joseph Lau, eds,

An Anthology of Translations of

Classical Chinese Literature, Volume I,

Columbia University Press, 2000, pp.658-659.

Note:

Mao Zedong was particularly fond of this story, and he instructed that it be included in the collection Stories About Not Being Afraid of Ghosts 不怕鬼的故事. For details, see here.

Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio 聊齋誌異

Pu Songling (蒲松齡, 1640-1715) wrote his Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio over several decades, during a life spent in obscurity in his home province of Shandong. The book amounted to nearly five hundred items of greatly varying lengths, from short anecdotes and jottings to fully fledged stories, on a wide variety of ‘strange’ themes. It was never published in his lifetime, and at first circulated in hand-copse versions. It was finally printed in 1766, in the southern city of Hangzhou, and was reprinted countless times, attracting many commentaries and imitations. It rapidly came to be considered the supreme work of fiction in the classical Chinese language, just as The Story of the Stone [aka, Dream of the Red Chamber] came to be considered the pinnacle of fiction in the vernacular.

— John Minford, trans. and ed.,

Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio,

Penguin Books, 2006.

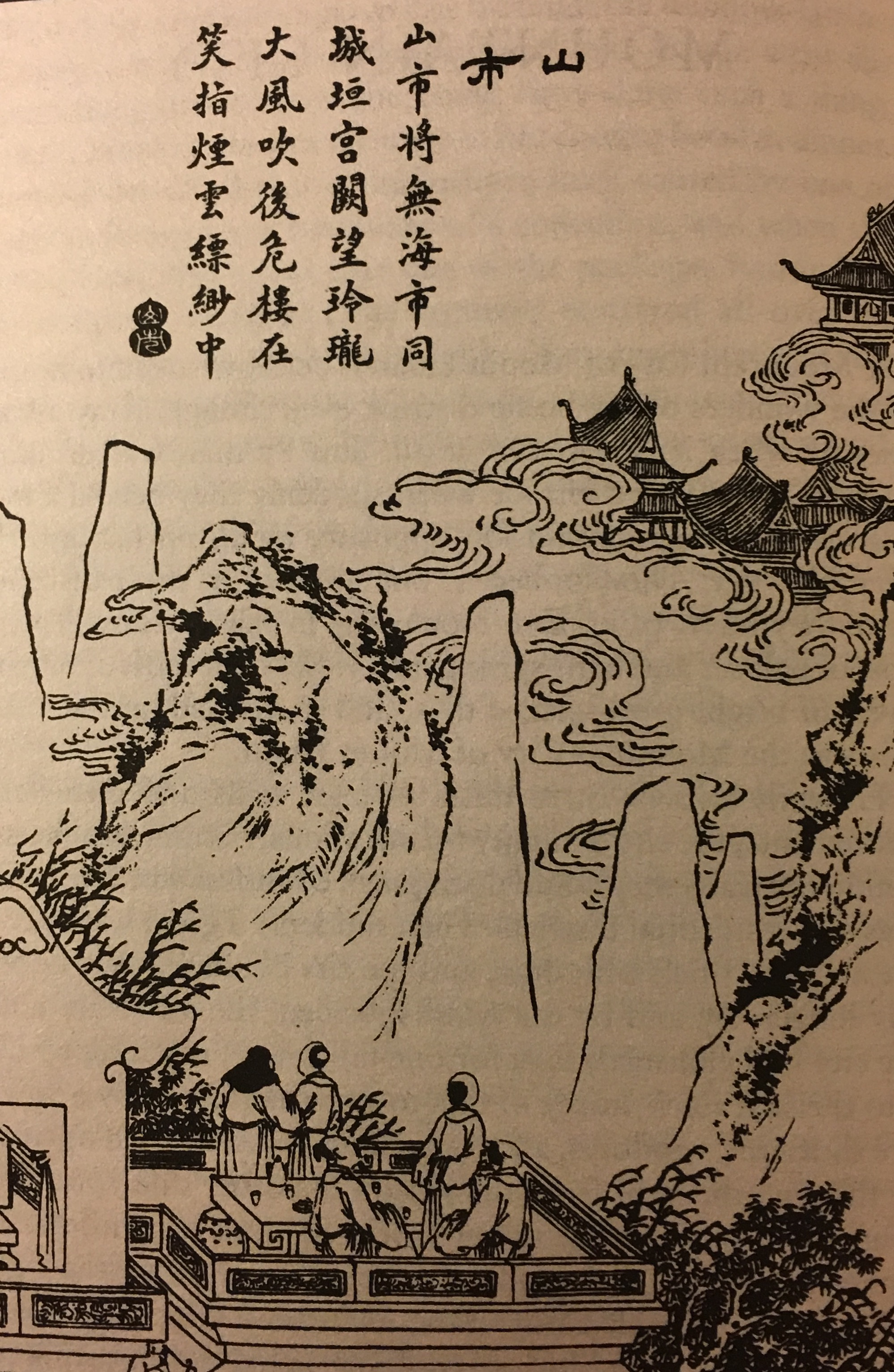

Mountain City 山市

The Mountain City of Mount Huan is acknowledged to be one of the wonders of my home district, even though may a year goes by when it is not seen at all. Sun Yu’nian was drinking with his friends on a terrace when suddenly they beheld a lone pagoda on the mountainside opposite, rising up far into the deep blue sky. They looked at one another in sheer disbelief, since they knew of no Zen monastery in that vicinity. Then a host of palaces and halls sprang into view, with roofs and flying eaves of bright green-glazed tiles, and it dawned on them that this was the Mountain City of Mount Huan. 奐山山市,邑八景之一也,然數年恆不一見。孫公子禹年與同人飲樓上,忽見山頭有孤塔聳起,高插青冥,相顧驚疑,念近中無此禪院。無何,見宮殿數十所,碧瓦飛甍,始悟爲山市。

Presently two or three miles of high walls and crenellated battlements, the city’s might fortifications, became visible, and within the walls they could distinguish countless storeyed buildings and residential districts. Then suddenly a great wind arose, the air grew thick with dust, and the city could scarcely be seen any longer. By and by the wind subsided, the air cleared, and the city had vanished, save for one tall tower, reaching up high into the sky. Each storey of this tower was pierced by a row of five shuttered windows, all of which had been thrown open and let through the light from the sky on the other side. One could count the storeys of the tower by the rows of bright dots. The higher they were, the smaller they became, until by the eight storey they resembled tiny stars, and above that they became an indistinguishable blur of twinkling lights disappearing into the heavens. It was just possible to make out figures on the tower, some hurrying about, coming and going, others leaning and standing in a variety of postures. 未幾,高垣睥睨,連亙六七裏,居然城郭矣。中有樓若者,堂若者,坊若者,歷歷在目,以億萬計。忽大風起,塵氣莽莽然,城市依稀而已。既而風定天清,一切烏有,惟危樓一座,直接霄漢。樓五架,窗扉皆洞開;一行有五點明處,樓外天也。層層指數,樓愈高,則明漸少。數至八層,裁如星點。又其上,則黯然縹緲,不可計其層次矣。而樓上人往來屑屑,或憑或立,不一狀。

A little while longer, and the tower began to diminish in size, until its roof came into sight. It continued shrinking still further to the height of an ordinary building, then to the size of a fist, then a bean, until finally it could not be seen at all. 逾時,樓漸低,可見其頂;又漸如常樓;又漸如高舍;倏忽如拳如豆,遂不可見。

There is also a story about an early morning walker who once saw the whole layout of the city — with its inhabitants, its markets, its shops. It was in no respect different from a city in our world. This is why it has also been called the City of Ghosts. 又聞有早行者,見山上人煙市肆,與世無別,故又名鬼市云。

***

Wailing Ghosts 鬼哭

At the time of the Xie Qian troubles in Shandong, the great residences of the nobility were all commandeered by the rebels. The mansion of Education Commissioner Wang Qixiang accommodated a particularly large number of them. When the government troops eventually retook the town and massacred the rebels, every porch was strewn with corpses. Blood flowed from every doorway. 謝遷之變,宦第皆為賊窟。王學使七襄之宅,盜聚尤眾。城破兵入,掃蕩群醜,屍填墀,血至充門而流。

When Commissioner Wang returned, he gave orders that all the corpses were to be removed from his home and the blood washed away, so that he could once more take up residence. In the days that followed, he frequently saw ghosts in the broad daylight, and during the night ghostly will-o’-the-wisp flickering of light beneath his bed. He heard the voices of ghosts wailing in various corners of the house. 公入城,扛屍滌血而居。往往白晝見鬼;夜則床下磷飛,牆角鬼哭。

One day, a young gentleman by the name of Wang Gaodi who had come to say with the Commissioner heard a little voice crying beneath his bed, ‘Gaodi! Gaodi!’ 一日,王生皞迪,寄宿公家,聞床底小聲連呼:皞迪!皞迪!

Then the voice grew louder. ‘I died a cruel death!’ 已而聲漸大,曰:我死得苦!

The voice began sobbing, and was soon joined by ghosts throughout the house. 因哭,滿庭皆哭。

The Commissioner himself heard it and came with his sword. 公聞,仗劍而入。

‘Do you not know who I am?’ he declared loudly. ‘I am Education Commissioner Wang.’ 大言曰:汝不識我王學院耶?

The ghostly voices merely sneered at this and laughed through their noses, whereupon the Commissioner gave orders for a lengthy ritual to be immediately performed for all departed souls on land and sea, in the course of which the Buddhist bonzes and Taoist priests prayed for the liberation of his supernatural tenants from their torments. That night they put out food for the ghosts, and will-o’-the-wisp lights could be seen flickering across the ground. 但聞百聲嗤嗤,笑之以鼻。公於是設水陸道場,命釋道懺度之。夜拋鬼飯,則見磷火營營,隨地皆出。

Now before any of these events, a gate-man, also named Wang, had fallen gravely ill, and had been lying unconscious for several days. The night of the ritual he suddenly seemed to regain consciousness, and stretched his limbs. When his wife brought him some food, he said to her, ‘The Master put some food out in the courtyard — I’ve no idea why! Anyway I was out there eating with the others, and I’ve only just finished, so I’m not that hungry.’ 先是,閽人王姓者,疾篤,昏不知人者數日矣。是夕,忽欠伸若醒。婦以食進。王曰:適主人不知何事,施飯於庭,我亦隨眾啖噉。食已方歸,故不飢耳。

From that day, the hauntings ceased. 由此鬼怪遂絕。

Does this mean that the banging of cymbals and gongs, the beating of bells and drums, and other such esoteric practices for the release of wandering souls are necessarily efficacious? 豈鈸鐃鐘鼓,焰口瑜伽,果有益耶。

Jottings from the Thatch Hut for Examining Minutiae

閱微草堂筆記

Ji Yun ( 紀昀, 1724-1805), who is perhaps better known with his sobriquets as Ji Xiaolan 紀曉嵐 or Ji Chunfan 紀春帆, was scholar-official and litterateur. He was a major figure in Qing cultural history and many anecdotes are recorded about him. These tales often feature ghosts and were almost certainly spawned by the fact that late in life he was inspired by Pu Songling’s Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio to compile his own collections of remarkable tales, many of which were held to be satirical portraits of prominent Neo-Confucian scholars.

Ji published five collections of supernatural tales between 1789 and 1798, and in 1800 the five volumes were produced under the collective title Jottings from the Thatched Hut for Examining Minutiae 閱微草堂筆記, an obscure title for an otherwise earthy and enjoyable collection of imaginative fiction. But he is better known for what was the magnum opus of Qing editorial achievement, Siku quanshu (The Complete Library in Four Branches). From 1773 onwards, Ji Yun edited this massive work together with Lu Xixiong, in compliance with an imperial edict issued by the Qianlong Emperor.

— from A Non-Princely Mansion from Qing-dynasty Beijing,

China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 12, December 2007.

The following episodes are from Real Life in China at the Height of Empire: Revealed by the Ghosts of Ji Xiaolan, translated by David E. Pollard, Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 2014.

***

A Drunken Ghost Gives Clue to Its Constitution

LYXXL II 14

It was night time when a butcher by the name of Xu Fang set down two crocks of wine he was carrying on his shoulder pole, and took a rest under a big tree. The moon shone bring as day. From some way off there came a kind of hooting sound, and a ghost of frightening aspect emerged from the shrubbery. 屠者許方,嘗擔酒二罌夜行,倦息大樹下。月明如晝,遠遠嗚嗚聲,一鬼自叢薄中出,形狀可怖。

Xu Fang hid behind the tree, gripping his shoulder pole in readiness to defend himself. The ghost came upon the crocks, and danced in delight. It wasted no time in opening one and draining its contents. Turning to the second crock, it had only got the stopper half out before it collapsed in a heap. 乃避入樹後,持擔以自衛。鬼至罌前,躍舞大喜,遽開飲,盡一罌,尚欲開其第二罌,緘甫半啓,已頹然倒矣。

Xu Fang was beside himself with fury, and guessing the ghost was now defenceless, he attacked it with his shoulder pole: it was like striking nothingness. As he rained hefty blows on it, its recumbent body gradually dissolved into a dense pool of vapour. Fearing it might still be capable of transformation, he hammered it with another hundred blows. The vapour spread out flat on the ground and gradually began to disperse, its remnant like pale ink, like diaphanous silk, thinning all the time, until not a trace was left, doubtless marking the ghost’s total extinction. 許恨甚,目視之似無他技,突舉擔擊之,如中虛空。因連與痛擊,漸縱馳委地,化濃煙一聚。恐其變幻,更捶百餘。其煙平鋪地面,漸散漸開,痕如淡墨,如輕榖,漸愈散愈薄,以至於無。蓋已澌滅矣。

In my view, ghosts are the vestiges of a person’s vital energy. This energy dissipates with the passing of time, which is why it is stated in the Zuo Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals that new ghosts are large, old ghosts are small. We know of people seeing ghosts, but I have never heard of them seeing ghosts that date back to far antiquity: that is because their vital energy had utterly dispersed. Alcohol is in itself a dispersal agent, which is why physicians use it as a supplement in medicines for quickening the blood, inducing sweating, treating depression and chills, and suchlike purposes. As for this particular ghost, its vital energy was on the wane, and was further dispersed through drinking a whole crock of wine: the dominant yang element in the wine caused turbulence and vaporized the weak yin, so total extinction was a matter of course. It was the alcohol that caused annihilation, not the beating. 余謂鬼,人之余氣也。氣以漸而消,故《左傳》稱新鬼大,故鬼小。世有見鬼者,而不聞見羲、軒以上鬼,消已盡也。酒,散氣者也。故醫家行血發汗、開郁驅寒之藥,皆治以酒。此鬼以僅存之氣,而散以滿罌之酒,盛陽鼓蕩,蒸煉微陰,其消盡也固宜。是澌滅於醉,非澌滅於捶也。

When I heard this tale I had with me a teetotaller. He commented: ‘A ghost’s form is volatile. It was due to the effect of alcohol that it fell down and suffered the beating. Men go in fear of ghosts, but being given to drinking, this one was subjugated by man. Wine bibbers should take note!’ 聞是事時,有戒酒者曰:鬼善幻,以酒之故,至臥而受捶。鬼本人所畏,以酒之故,反為人所困。沈湎者念哉!

A heavy drinker was also present. He said: ‘Though ghosts have no substantial form, they still have consciousness, so they are not free from the swings of emotion. In falling down dead to the world and gravitating to oblivion, this ghost was discovering its proper nature. One can look for no greater fulfilment from drinking than this. The Buddhists regard nirvana as the highest bliss: what do those who hurry and scurry know of that!’ 有耽酒者曰:鬼雖無形而有知,猶未免乎喜怒哀樂之心。今冥然醉臥,消歸烏有,反其真矣。酒中之趣,莫深於是。佛氏以涅槃為極樂,營營者惡乎知之!

I imagine this would be what Zhuangzi meant by ‘This is one way of looking at things, that is another way’! 莊子所謂此亦一是非,彼亦一是非歟。

***

Ghost Hermitage 鬼隱

LYXXL VI 10

Dai Zhen contributed this. 戴東原言。

Towards the end of the Ming dynasty a gentleman named Song penetrated deep into the mountains of She county in Anhui province while exploring for a propitious grave site. As dusk fell storm clouds gathered, and seeing a cave at the foot of an escarpment, Song made for it to seek shelter. A voice issued from inside the cave, announcing: ‘A ghost lives here, you had better keep out.’ 明季有宋某者,卜葬地,至歙縣深山中。日薄暮,風雨欲來,見崖下有洞,投之暫避,聞洞內人語曰:此中有鬼,君勿入。

‘So what are you going in there?’ Song inquired. 問:汝何以入?

‘I am a ghost!’ 曰:身即鬼也。

Song asked if they could get acquainted. The ghost responded: 宋請一見,曰:

‘Your yang aura and my yin aura will conflict if we come together, and you would be sure to suffer a nasty chill. I suggest you light a fire as a precaution, and sit at some distance from me while we talk.’ 與君相見,則陰陽氣戰,君必寒熱小不安,不如君癎火自衛,遙作隔座談也。

When they were settled, Song asked:

‘How come you live here? Surely you have a grave to go to?’ 宋問:君必有墓,何以居此?

‘I served as magistrate in the Wanli period [1573-1619]. The way my fellow officials fought over spoils and intrigued for preferment disgusted me, so I resigned from my post and stayed home for the rest of my days. On my death I pleased with the King of the Nether World to spare me from reincarnation, and was allowed to exchange the rank and salary due me in the next life for an official position down below. What would you know, the greed and rivalry there was still the same! So I resigned again, to retire to my grave. But I could not put up with the awful racket the horde of ghosts made milling about in the cemetery, and had no choice but to seek solitude here. Though cold wind and endless rain make it bleak and comfortless, it is a paradise compared to the turmoil of officaldom and the traps and pitfalls of common life. Being all by myself in these barren hills, I even forget what year it is. I couldn’t say how long ago it was I cut myself off from ghost land, and am even vaguer when I left mankind behind. I have luxuriated in being released from all worldly ties and able to immerse myself in nature. But now that humankind has made tracks to my haven, I shall have to move on again on the morrow. This peaceful sanctuary is lost to me forever!’ 曰:吾神宗時為縣令,惡仕宦者貨利相攘,進取相軋,乃棄職歸田。歿而祈於閻羅,勿輪迴人世,遂以來生祿秩,改注陰官。不虞幽冥之中,相攘相軋,亦復如此,又棄職歸墓。墓居群鬼之間,往來囂雜,不勝其煩,不得已避居於此。雖淒風苦雨,蕭索難堪,較諸宦海風波,世途機穽,則如生忉利天矣。寂歷空山,都忘甲子,與鬼相隔者,不知幾年,與人相隔者,更不知幾年。自喜解脫萬緣冥心造化,不意又通人跡,明朝當即移居。武陵漁人,勿再訪桃花源也。

The ghost refused to be drawn further, and even ignored Song’s inquiry after his name. Song had brush and ink with him; before he left he wrote two big characters over the mouth of the cave: Ghost Hermitage. 語訖,不復酬對,問其姓名,亦不答。宋攜有筆硯,因濡墨大書鬼隱兩字於洞口而歸。

***

Ghost Portraits 畫鬼

LYXXL II 24

Luo Liangfeng of Yangzhou is able to see ghosts. He says: 揚州羅兩峰,目能視鬼,曰:

Everywhere there are people, there are ghosts. Grim ghosts who have died a violent death, and have been suspended in limbo for many years, are mostly found in isolated and unoccupied buildings. They should be given a wide berth, because they will attack you. The common sort of ghost who drifts about aimlessly seeks the shade of walls in the forenoon, when the yang element is in the ascendant, but in the afternoon when the yin element dominates, wanders off in all directions. They can pass through walls at will, avoiding the use of doors, and if they encounter human beings they will give way to them, being afraid of their yang aura. These ghosts are found all over the place, and are not harmful.’ 凡有人處皆有鬼。其橫亡厲鬼,多年沉滯者,率在幽房空宅中,是不可近,近則為害﹔其憧憧往來之鬼,午前陽盛,多在牆陰,午後陰盛,則四散遊行,可穿壁而過,不由門戶,遇人則避路,畏陽氣也,是隨處有之,不為害。

Luo goes on to add: 又曰:

Ghosts of the latter type congregate in densely populated places: I have rarely seen them in the wilds. They prefer to gather round kitchen stoves, presumably to enjoy the scent of food. they also favour latrines, I don’t know why — perhaps because humans don’t go near them more than necessary? 鬼所聚集,恒在人煙密簇處,僻地曠野,所見殊稀。喜圍繞廚灶,似欲近食氣。又喜入圂廁,則莫明其故。或取人跡罕到耶。

Mr Luo has published an album of Portraits from the Spectral Zone, which one suspects to have been painted from imagination. One portrait shows a spectre whose head is enormously bigger than his body, which seems particularly fanciful. Yet I remember my late father telling of a Mr Chen from Yaojing who had his window shutters hooked back when he retired to bed one summer night. The window was all of ten feet wide. Suddenly a gigantic face looking in through it, filling its whole space; where and how its body was positioned could not be seen. Chen snatched up his sword and stabbed at the apparition’s left eye. The apparition receded before this thrust, and disappeared. An old servant witnessed this incident from his room opposite: according to him, the apparition rose up from the ground under the window. They therefore dug a hole ten feet deep on that spot, but found nothing. 所畫有《鬼趣圖》,頗疑其以意造作,中有一鬼,首大於身幾十倍,尤似幻妄。然聞先姚安公言,瑤涇陳公,嘗夏夜掛窗臥。窗廣一丈,忽一巨面窺窗,闊與窗等,不知其身在何處,急掣劍刺其左目,應手而沒。對窗一老僕亦見,云從窗下地中湧出,掘地丈餘,無所睹而止。

So the existence of such a spectre was after all authenticated, but I confess I am out of my depth in this nebulous sphere: would that I knew where to turn for counsel! 是果有此種鬼矣。茫茫昧昧,吾烏乎質之。