The following interview, conducted by Sang Ye 桑曄, first appeared in China Candid: the people on the People’s Republic, edited by Geremie R. Barmé with Miriam Lang, University of California Press, 2004.

…AND THE DEAD

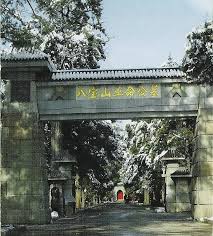

A forty-seven year-old undertaker at Babao Shan 八寶山公墓, the main crematorium and cemetery in Beijing.

The government started promoting cremation in the 1950s. Chairman Mao took the lead by signing a document requesting that his body be cremated when he died.

In practical terms, we here at the Babao Shan Public Cemetery were the first in the business in Beijing. That’s why people still refer to us as the Babao Shan Crematorium.

None of the people who originally worked here are still alive. Some made it to up to retirement age; others died before they got there. After having burned people day in day out all their professional lives, finally it was their turn. But that’s the nature of the job: the more you burn the fewer there are. To go up in flames in your own work unit, now that’s what I call a real convenience. But, in the end Chairman Mao wasn’t cremated, even though the other leaders were. And they built a memorial hall for him as well. That was really going a bit too far.

A few years before Xiaoping died [in 1997] they instituted simplified funeral procedures for the leadership. No more big send-offs, no memorial meetings, just a standard leave-taking of the corpse. Even Xiaoping’s funeral was pretty basic, so now no one can complain about discrimination. If you cut it back to a simple leave-taking you make things easier all around. If you hold a memorial service there’s always going to be a big fuss about the wording of the official memorial speech. The corpse may be lying there stone cold, but all the family members will be in a heated frenzy disputing with the deceased’s work unit about what will be in the funeral oration. All anybody really cares about is how they can make the corpse work for the living. The negotiations go back and forth. Was the deceased’s departure ‘an incalculable loss,’ ‘a severe loss,’ or just ‘a great loss’? For all they know, the work unit probably doesn’t think it was a loss at all; since they don’t have to pay them wages any more, they haven’t lost anything.

You shouldn’t make too much of yourself, that’s what I say. Don’t think you’re such a big deal when you’re alive, and don’t expect people to make a fuss over you when you’re dead.

The living come in here to have a look around and then go home again; the dead come in, spend a bit of time and then they take their leave too. It’s just that they exit as a wisp of smoke. For those of us working here life and death are all much of a muchness really. Although we actually do cremate people here, just about everything else we do here is similar to the kind of fakery you get in the society at large. There’s nothing real; it’s all ritual, procedure — it’s all a show.

It’s a good job and I like working here. There’s always plenty to do; the market’s stable, supply steady, and we always show a profit. The wages, conditions of employment and suchlike are not too bad either. Nowadays lots of work units are going bankrupt or being forced to retrench workers. But one thing’s for sure: we’re never going to go under. If we go belly up the streets’ll be full of rotting corpses.

My general impression is that there are simply too many Chinese. Nowadays even cremations are divided up according to districts. If you die in the east of the city that’s where you’ll be cremated; if it’s in the west you’ll be sent over here. You might think you’d like to go up in smoke over in Babao Shan, but if you’ve died in the wrong part of town you can forget about it. When all the fireworks are over the family is allowed to leave the ashes here on deposit for two years. After that they either have to buy a plot here or, if they can’t afford it, they have to remove the ashes.

In my line of work the only thing you really have to be careful about is to never, ever show your anger. No matter what the sons-of-bitches do you should never lose your temper. If they want to rent memorial wreaths, that’s fine by me, we’ll supply them. If they want the death march to be played, I’ll play it. If they want to buy one of our urns for the ashes, I’ll sell it to them. If it’s too expensive, fine, I’ll find a cheaper one. If they’re grief-stricken, I’ll console them; if they want to pick a fight with someone, I’ll try and calm them down. I have it all down pat. I might be thinking to myself: ‘Fuck you, asshole!’ but I’ll jolly them along and get things out of the way without a hitch.

When I returned to Beijing after having been in the countryside in 1977 I was an angry young man. But a job like this slowly wears you down; it leaches all the anger out of you. You learn that sooner or later we all go up in smoke, so why even bother saying ‘Fuck you, asshole!’ out loud?

Just before they take receipt of the ashes I have to ask the mourners whether the deceased was a Communist Party member or not. We have a regulation that says party members get a red flag on their urns, while non-party people get a piece of yellow cloth. If the family say the deceased was in the party, I’ll take them at their word. By now they’ve gone up in smoke, after all, so who cares if they’re only a pretend party member? The colors might be different, but they cost the same.

Take your pick; you can have whichever one you want.

— translated by Geremie R. Barmé