Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

The following essay by Xu Zhangrun has been translated with the author’s permission.

***

In His Dark Materials — a trilogy by the novelist Philip Pullman — the concept of ‘Dust’ or ‘Rubashov Particles’ is used to indicate consciousness and independent thought. The Magisterium — a joyless, inhumane and authoritarian theocracy — regards Dust as being related to Original Sin and therefore to heresy. At every turn, the Magisterium attempts to outlaw and destroy Dust. As in Pullman’s fictional world so too in real life China today: no matter how tireless the efforts of those who wield the broom, Dust can never be completely swept away.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

6 December 2019

***

Further Reading:

- Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

***

On Dust

Dust came into being when living things became conscious of themselves; but it needed some feedback system to reinforce it and make it safe, as the mulefa had their wheels and the oil from the trees. Without something like that, it would all vanish. Thought, imagination, feeling, would all wither and blow away, leaving nothing but a brutish automatism; and that brief period when life was conscious of itself would flicker out like a candle in every one of the billions of worlds where it had burned brightly.

— Philip Pullman, The Amber Spyglass, Chapter 34

***

Dust and Spring in Beijing

面對這個春天,我束手無策

The Master of Erewhon Studio

無齋先生

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

In this Jihai Year of the Dog spring arrived with its annual promise. The prospect of the season suffused the world, enticing even the most reluctant to celebrate its bounty.

Over night, parasol trees budded with new growth, branches of peach blossomed and willows trailed their tendrils. Life thus renewed, glimmers of hope even sparkled in the darkling recesses of my mind. I found myself drawn to venture out. Just then — although it was hardly unexpected — the Powers-that-Be at Tsinghua University banned me from taking on new research students. A lifetime devoted to the routine duties of pedagogy was thereby rudely terminated. It was as though a mountain had come crashing down on me. Given the season, perhaps I should compare that the severity of their ban to those vicious dust storms that pummel Beijing during the spring. Now I experienced for myself the true meaning of that expression: ‘in the twinkling of an eye warm embraces are torn asunder by frosty disregard’. But their interdiction also afforded me a new perspective. Three decades at the blackboard in a whirl of chalk dust was relegated to the past. For now, at least, I could take a breath; I had been unencumbered.

己亥春到,心意溫煦,而势必景致絡繹,怎忍耽誤。說話間,新桐初引,桃紅柳嫩,人間重又生氣遊走,誘出沉埋心底的希望星星點點。突然,但並不意外,校方下令停止我的教研招生,大半輩子起居校园,教書匠職業生涯就此告一段落。禁令如山倒,恰如春天的風沙,自北國撲殺而來。它們逼迫我不得不体味乍暖還寒之意,卻也讓我獲得了冷眼旁觀的機緣。卅載碌碌,跟黑板粉筆打交道,此刻倒仿佛松了一口氣,一身輕呢。

It had never occurred to me — indeed, how could it? — that, as I approached my sixtieth year, life would throw up this unexpected vista, and one so tenebrous. So I chose to seek solace in poetic fancy and nature while busying myself also with quotidian minutiae.

It is to You, Heavens Above, that I must express gratitude!

沒想到,想不到,年近花甲,不期然間,人世再向我展示一层风景,人性由此往幽微更掘一层。於是,沉吟風月,打理家常。

哦,上蒼,我該怎樣感恩!

***

***

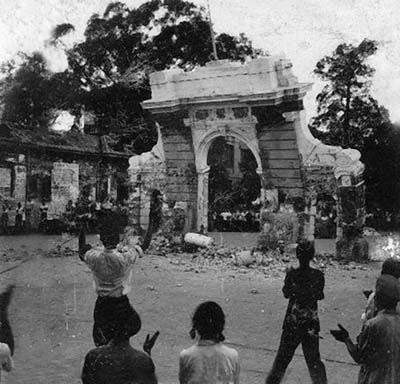

The market of Zhaolan Yuan is located on the other side of the creek just south of the original main gate of Tsinghua University. During the tumult of the Cultural Revolution, that gate — long since made redundant by the expansion of the university campus — was deemed to be one of the ‘Four Olds’: something belonging to the reactionary past. That’s why a hoard of Party Gentry Red Guards took it upon themselves to demolish it. Years on, in 1991, as part of the commemorations of the founding of the university, a new gate was built on the site of the old as a simulacrum of the original.

Just outside the old gate, two compounds — Zhaolan Yuan and the neighbouring Xinlin Yuan — had been built in the years before the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949 to house professors and their families. Both the two-story Western-style buildings of Zhaolan Yuan and the single-story Chinese courtyards of Xinlin Yuan were stand-alone structures with separate entrance ways and sequestered gardens. Even the relatively elegant names of the compounds — Zhaolan, ‘Reflected Waves’; and Xinlin, ‘New Forest’ — hinted at the temper of that earlier age, the Republic of China.

Many tales are told about the prominent academics who had lived there and the memoirs of the political historian K.C. Hsiao in particular contain accounts of that era [see 蕭公權, 《問學諫往錄》]. There’s also any number of colorfully embroidered stories about the ‘Wives’ Salons’ of faculty members; they beguile and entice China’s literary youth to this day. The original inhabitants could never have imagined that the old residential compounds of Tsinghua faculty would, over time, turn into unseemly tenements crowded with just about any and everyone other than academics. One of the more prominent buildings in the area — a jerrybuilt construction slapped together with the most mean materials — boasts a supermarket on the ground floor. The upper stories are taken up by eateries. The Zhaolan Compound Market which was destination of my outing invariably teems with activity from dawn to dusk; the endless round of consumption and replenishment means that it is little better than a public convenience.

照瀾院菜市場在二校門的南面,清華園的中心。所謂“二校門”,是老清華初建時的校門,後來校園增擴,跨疆越界,遂成虛設。“文革”潮湧,例为“四旧”,为權貴學生率眾砸毀,直至二十五年後校慶時分方始原樣複建。對門隔溪,當年老清華陸續修建起照瀾院、新林院兩處教授住宅小區。前者為西式兩層紅磚小樓,後者則為灰瓦磚石單層中式。一律獨門獨戶,前庭後院,逶迤散布。而命名雅致,一望可知是民國才有的風流。其間故事,蕭公權先生回憶錄曾有深情憶敘,更有那所謂“太太的客廳”濃墨重彩的渲染,晃兮恍兮,叫现今的文青痴绝。不料半個世紀下來,卻逐漸蛻變成大雜院,住戶也早非教書匠。就近一幢樓,形体粗陋,近些年的濫制,底層菜市場,樓上兩層餐廳,晨夕熙攘,五穀輪回,是为“照澜院菜市场”也。

On the day in question there was no hint of wind as I had strolled southwards through the campus. With my purchases from the Zhaolan Supermarket secured in my shopping bag I was retracing my steps and on my way home at a fairly leisurely pace when I happened to bump into an acquaintance. Although we both worked at Tsinghua, we were usually so busy that our paths rarely crossed. On this occasion, however, this fine gentlemen happily took the time to have a chat. For my part, I couldn’t have been more grateful for this simple kindness.

So, there we were: two middle-aged fellows exchanging commonplaces about the unfolding delights of spring and the encroaching absurdities of human design. We found comfort in the fact that the weather was excellent and, what mattered, after all, was we were both hale and hearty. There was no good reason to eschew the verdant delights of the season. Surely, it was an ideal moment to take a skiff out on the water and enjoy a libation… And so the conversation unfolded, smiles lighting up our features. We ranged over many topics and chortled loudly as we did so. Buoyed by the fortuitous encounter we bid adieu in high spirits.

今日無風,穿過校園。買好菜,拎包出門,緩步當車,迎面碰上一位熟人。同校做工,各自埋頭,倒不常見。閣下依然樂意接談,在下當然感激不盡。兩個中年漢子,感喟天行有常,而人事詭譎,既然天氣晴好,身體最要緊,不妨沿坡踏春,引觴泛舟。彼此莞爾,怡怡然也。如此這般,大聲嘻哈,一陣喧阗,擊掌告別。

I had not gone five metres more when I encountered an old fellow in one of those electric mobility vehicles. As we approached each other I noticed that there was something in his mien that belied his air of seeming indifference. The old boy radiated vitality: he was a substantial figure and sported a full head of silver curls; the sole evidence of any frailty was his obvious lack of mobility. Directing himself straight at me he stopped and asked:

‘Are you the Xu Zhangrun they’re talking about?’

From the tone I was unable divine his intention, so I bent forward to confirm my identity courteously. Thereupon, he fixed me with a glare — it might only have been a few seconds, though it seemed to go on for ages. Then he recited a line at me, spitting out the words with clarion precision:

‘Everything reactionary is the same; if you don’t hit it, it won’t fall. This is also like sweeping the floor; as a rule, where the broom does not reach, the dust will not vanish of itself.’

五米開外,老者端坐電動輪椅,冷眼旁觀,仿佛無意,似乎有心。此刻扶輪驅前,以“你就是許章潤?”相問,不溫不火,有張有馳。趕緊俯身,唯唯諾諾。老人家白髮蜷曲,身板寬大,面色红润,可惜不良於行。盯著我三、五秒,或者六、七秒,然後,一字一頓,從牙縫裡吐出:

凡是反動的東西,你不打,他就不倒,如同掃地,掃帚不到,灰塵照例不會自己跑掉。

It was a well-known quotation from the ‘Great Leader Mao Zedong’, one that, back in the day, people could rattle off without hesitation. You also heard it blasted from loudspeakers day in, day out, and it was chanted stentoriously at Struggle Sessions and Denunciation Meetings alike. The chanting was usually followed by punches and kicks, or it might be accompanied by wooden clubs or steel pipes, all of which rained down on whatever hapless Reactionary was being victimised. I also well remember that it was this particular quotation — vicious mantra that it was — that was changed in shrill tones just before they ransacked a home or an apartment.

As for ‘The Dust’ — that is the people to be ‘swept away’ by Revolution — they were, quite literally, scared shitless by these words. It invariably meant a beating; many ended up black and blue, some were even killed. Would everyone live, or may everyone die — it was all in the luck of the draw. After all, a Reactionary was, by definition, beyond the pale, a non-human, and the power of life and death was in the hands of others. In that topsy-turvy world, however, the very people who attacked others as ‘Dust’ needing to be swept away, might just as easily end up as victims themselves; then they would find themselves also being treated as ‘Reactionary Dust’. That is why at the time ‘politics was not coterminous with the walls of the polis’; barbarity encroached on everything; humanity itself was despoiled; the meat-grinder chewed up everything that fell into its hungry maw. That was how China launched itself into a return to atavism. Forget that talk about the gradual unfolding of evolutionary change or the millennia of the civilising process, for in China, overnight, it all counted for naught. We regressed collectively, our behaviour undeniable evidence that we could easily submit ourselves to the law of the jungle.

Although [having been born in 1962] for the most part I avoided things at the time, nonetheless, I did see and experience enough for myself. Even now, whenever I recall that era a tremor courses through me and a baleful sigh escapes my lips. Nonetheless, it had been many long years since I had heard that particular Mao Quote; in fact, I’d all but forgotten it. Yet now, here, right in front of me, was an old boy ensconced in his electric scooter incanting those dire words with earnest malice. It was like crossing paths with a malevolent night wraith, one who had the temerity to venture out in the full glare of daylight.

這是“偉大領袖語錄”,當年人人會背,晝夜喇叭廣播。但逢“批鬥”,每場必嚎,而繼以拳打腳踢,棍棒交加。猶記抄家之際,動手前必也高聲誦唱同一咒語。灰塵們屁滾尿流,頭破血流,乃至一命嗚呼,瞬息陰陽兩隔。既屬“反動的東西”,人不人矣,則生殺操於他手,早已超出文明論域。尤有甚者,今日開口動手的,明天就可能角色反轉,同為灰塵矣。故爾,此非“城邦之外無政治”,而是野蠻複歸,人文頹敗,絞肉機反噬,演繹的是一幅活脫脫人類返祖圖景也。萬年風雨進化,千年文明馴化,不敵一夜間野蠻性發作之退化,說明我們距離叢林不遠,從來就不遠。余生也晚,卻不幸遭逢,親歷親見,每每想起,輒脊背發涼,感喟幾希。不過,確乎早已多年不曾聽聞,好像忘了,今日突自輪椅老者口中字字咬出,恍如白日見到厉鬼。

I had no idea who he was or why he had taken it upon himself to confront me with a Maoism like that. Having thus unburdened himself he seemed to relax — daresay he was pleased that, in his mind at least, that he had scored some kind of victory. For my part, the encounter left me careening between shock and perplexity; in my mind outrage and pitying contempt mixed in equal measure. As I was reeling he set off in his vehicle, though I thought I could hear him mumbling something, as if in a brume of self-approbation.

老者姓甚名誰,為何朝我口誦“領袖語錄”,在下一概不知。而一襟愁緒,陽關三疊,萬里覓精神,則一切似乎又頓時顯豁,遂了然於心。話說愕然而惘然之際,憎惡與憐憫兩頭,他已駕車轉向,悠然離去,依稀哼哼有聲,樂陶陶也。

I’ve always thought of myself as being rather naïve, as being someone with limited experience, not particularly world wise. At that moment, I found myself cast into something like a temporal daze — time and space swirled around me, the quick and the dead were confounded in a blur. Later, as the spring light faded I looked out into the distance: to think that we had all lived through similar things — sorrows authored by political strife; the heartache of broken families — and so then this endless entanglement.

章潤這娃經事有限,閱世短淺,只覺得霎那間時光錯亂,空間迷蒙,三界不分,人鬼無別矣。煙光殘照,憑欄望極,共此關山月,惟寄千絲萬縷。

Spring has arrived and with it there is a burgeoning of life. Yet here, here on this beautiful campus, I find myself to be experiencing a season that is as relentless as it is silent. So confronted, I find that I lack the wherewithal to respond.

春來了,萬物復蘇。可在這個美麗校園,面對這個聒噪而無聲的春天,我束手無策。

Drafted on the 11th of April 2019

Revised on the 29th of November

While visiting Shanghai

二零一九年四月十一日初稿,

十一月二十八日改訂於滬上旅次

***

A Note on The Master of Erewhon Studio 無齋先生

As we noted in And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing! (China Heritage, 10 November 2018), Xu Zhangrun’s studio name is 無齋 wú zhāi, literally, ‘The Studio That Isn’t’. The author has remarked that in his previously stretched circumstances, when his family lived in cramped quarters, he had no study — 齋 zhāi, ‘studio’, as such places for private creative pursuits are known — or even a settled place for his academic research and writing. Thus, when he did finally have a study, he decided to call it 無齋 wú zhāi, literally, ‘The Studio That Isn’t a Studio’, alternatively, No Study, Non-existent Studio, or even Nothingness Studio. That is to say, it was a place for study that was both nowhere and everywhere. (For more on studios in Chinese culture, see: Zhai, the Scholar’s Studio, China Heritage Quarterly, No.13, March 2008.)

I translate 無齋 wú zhāi as ‘Erewhon Studio’. ‘Erewhon’ is a garbled version of the word ‘Nowhere’, as well as being the title of a novel by Samuel Butler published in 1872. A satire of Victorian social mores, the book was about ‘nowhere in particular’; Butler’s fictional ruminations are thought to have been inspired in part by his time in New Zealand. ‘Erewhon Studio’ thus links Xu Zhangrun’s prose, with its satirical undertow and utopian aspiration, and New Zealand, a distant island nation where China Heritage is produced. Of course, Xu Zhangrun’s feuilleton, which are produced ‘no-where’, are really about ‘now-here’.