Hong Kong Apostasy

In late-1970s Hong Kong, if you lived in a basement apartment and worked in a subterranean editorial office, like I did, you often heard the word gaat6 zaat6, the Cantonese term for ‘cockroach’. Not surprisingly, the various ways and means of combatting the omnipresent health threat of cockroaches was a major feature of local advertising, so you also soon learned the unforgettable written form of gaat6 zaat6 — 曱甴 (alternatively 甴曱). The pronunciation of these characters is far less punchy in Standard Chinese: yuēyóu. Anyway, in the North, cockroaches are most commonly called 蟑螂 zhāngláng.

In the early 1990s, 曱甴 gaat6 zaat6 earned a ‘pet name’; they came to be known as 小強 siu2 koeng4, ‘Little Toughs’. The origin of the expression is to be found in a popular 1993 comedy starring Stephen Chow (周星馳, 1962-). In Flirting Scholar (唐伯虎點秋香 Tong4 Baak3fu2 dim2 Cau2heong1) Chow plays the eccentric late-Ming artist Tang Yin 唐寅 (aka Tang Bohu, 唐伯虎) who has a pet cockroach called ‘Little Tough’. The name resonated with Hong Kong audiences and it entered popular diction not only because it was a cute sobriquet for a ubiquitous but unpopular creature, but also because of a grudging recognition that cockroaches are indeed tough, so much so that they are all but impossible to eradicate.

***

***

During the 2019 Anti-Extradition Bill Protest Movement in Hong Kong, the local constabulary were heard to refer to protesters as ‘cockroaches’ 曱甴 gaat6 zaat6. Like those ubiquitous and tough household pests, the demonstrators proved to be ever present, always underfoot (or in your face), resilient, recalcitrant, unfailingly annoying, hazardous and, for all intents and purposes, irrepressible.

As the frequency and intensity of protests escalated, on 25 July, Lum Chi-wei 林志偉, chair of the Junior Police Officers Association 香港警察隊員佐級協會 (generally known simply as ‘The Fist Club’ 拳頭會) declared that demonstrators ‘should not be called human beings’; in fact, they were little better than ‘cockroaches’ 蟑螂 (see《譴責侮辱國家行為及暴力衝突升級》). The pro-Beijing local media preferred the colloquial Cantonese term and took to describing them as gaat6 zaat6 曱甴 and ‘locusts’. Actually, the term was ‘Yellow [Ribbon] Insects’ 黃蟲. The ‘Yellow Ribbon Faction’ 黃絲派 are supporters of the protests, while ‘Blue Ribbons’ 藍絲 support the police. ‘Yellow Insect’ was a happy homophone for ‘Locust’ 蝗蟲, an expression Hong Kong people used from around 2012 to describe Mainlanders who had swept up bulk supplies of milk powder due to fears of contaminated milk powder across the border. The use of ‘Locusts’ elicited an outraged reaction in the north and, in turn, in early 2012 Kong Qingdong 孔慶東, a Peking University academic with a sideline as a notoriously foul-mouthed media pundit, denounced Hong Kong people as post-colonial lackeys who were little better than ‘dogs’.

Such vituperation coming from a creature of autocracy known for his exaggerated self-regard and fustian rhetoric segued neatly into what is now hailed as the New Era of Xi Jinping, one that actually promotes ‘The Closing of the Chinese Mind’ (pace Allan Bloom). Kong played an early role in aiding and abetting those who would reinforce deeply ingrained cultural and political biases in service to the needs of the overweening centralised state. The language of contempt, dismissal and denigration of ‘the south’ also dovetails comfortably with ancient prejudices regarding ‘southern barbarians’ 南蠻 and imagery related to liminal territories previously deemed to be beyond the control (and supposedly ‘civilising influence’) of State Confucianism. Now, China’s southern peripheral outpost demonstrated that it was emulating Tibet and Xinjiang by rising up in its resistance to an increasingly jealous party-state. Here then is China’s true ‘clash of civilisations’; it is also an aspect of what, in reality, is a long term war of attrition, a struggle sparked by increased internal colonisation that, in the case of Hong Kong, came to a head in 2019.

***

On 22 August 2019, a police spokesperson admitted at a daily press briefing that members of the Hong Kong police did, indeed, refer to protesters as gaat6 zaat6 曱甴. While mayhem reigned in the streets, and police violence went unchecked, the spokesperson’s reassurances were inapposite and he impotently declared that local citizens should all be treated with civility and respect. He argued that his own courtesy was always on display because he made a habit of addressing the individual journalist who gathered for the briefings as ‘Mister’ and ‘Miss’ respectively (he did not evince any awareness for intersectionality).

***

For aficionados of the 1989 Beijing Protest Movement, the militant heroism of Hong Kong protesters will recall the actions of the ‘Dare-to-Die Squads’ 敢死隊 (the best known of these was the ‘Flying Tigers’ 飛虎隊) and others determined to rage against the system to the bitter end, or 死嗑 sǐ kē. Desperation and desperate means are hardly unique to the Chinese situation. The Hong Kong protesters, however, present an historical paradox: they are protesting not simply for a better future so but also agitating in favour of a status quo ante.

We conclude this chapter of our series ‘Hong Kong Apostasy’ with ‘The Sound of Silence’, posted by Simon Shen 沈旭暉 on ‘Simon’s Glos World’. Our thanks to Reader #1 for bringing this sad meditation to our attention and to Victor Fong 方金平 for suggesting refinements to the translation.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

1 September 2019

***

Further Reading:

- 陶傑, ‘廢老和廢青’, 《蘋果日報》, 12 January 2019

- ‘曱甴 vs 甴曱’, Cantonese Museum 廣東話資料館, Facebook, 8 November 2018

- ‘警察員佐級協會強烈譴責侮辱國家行為及暴力衝突升級’, 《信報》, 26 July 2019

- 吳志森,‘巧合定夾埋 低級警員協會多次叫「抗爭者」做蟑螂 白衣人無差打人又叫趕甴曱’,YouTube, 4 August 2019

- ‘警員對講機以「曱甴」形容示威者 警方:字眼不理想’, 《立場新聞》, 22 August 2019

- ‘長期不被尊重 — 年輕人冒死抗爭的遠因’,《立場新聞》, 28 August 2019

- 伍桂麟, ‘當年輕人問我如何寫遺囑及身後安排,我心知不妙!’,《立場新聞》, 31 August 2019

- Megan K. Stack, ‘Bravery and Nihilism on the Streets of Hong Kong’, The New Yorker, 31 August 2019

***

The Dragon Slaying Brigade

An Exclusive Interview with the Armed Militant Group

Among the Bravehearts of the Resistance

專訪: 勇武派中的武鬥派

名叫「屠龍」的這群人

The Stand News

Translated and annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

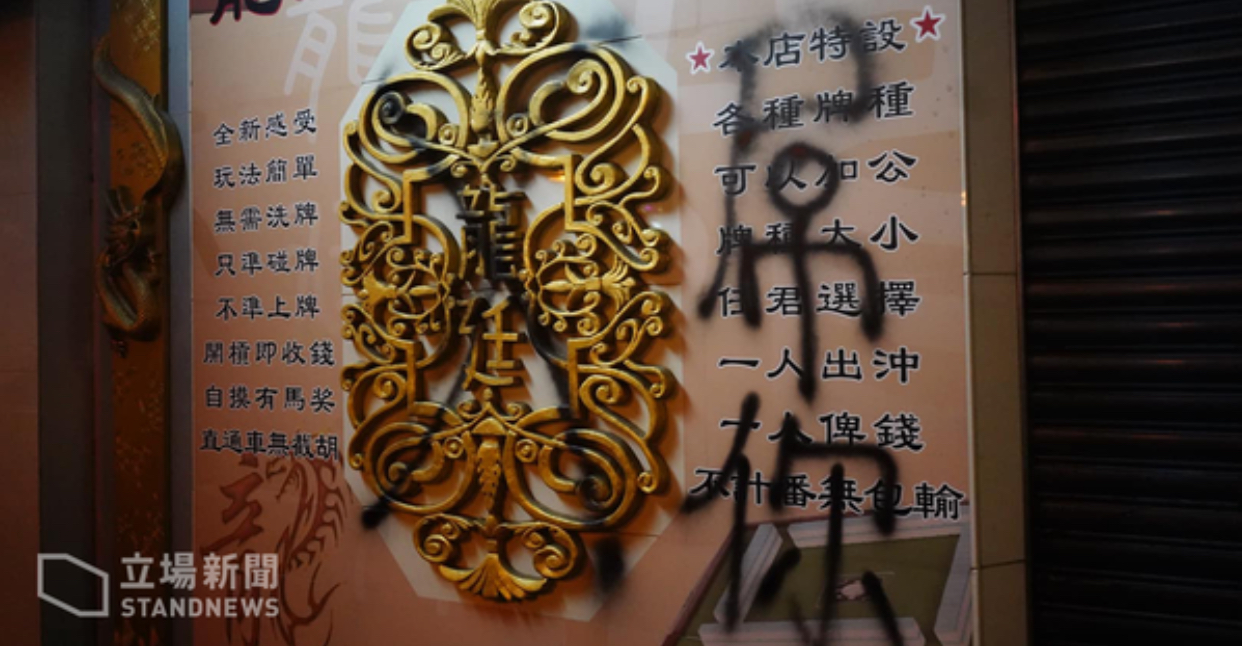

In the aftermath of the Tsuen Wan-Kwai Tsing mass demonstration on 25 August, a mahjong parlor at Yi Pei Square was trashed and the metal shutters of shops at Tai Pei Square were broken open. Police were ordered to the scene where they were greeted by a squad of young people in ‘full protest battle gear’ who used metal bars and traffic cones to shatter the windows of the police vehicles. The police commander was beaten with a metal rod and, in the ensuing mêlée, one policeman fired a live round of ammunition into the air. This was the first time during the months of protests that a hand gun had been fired.

[Note:

‘In Tsuen Wan, an area with a high proportion of low-income mainland migrants and links to triad gangsters, where protesters had previously been attacked, a dozen men wielding metal poles and clad in white and blue tops appeared in the area, with some holding the Chinese national flag. They dispersed shortly after riot police intervened.’

— from Austin Ramzy and Raymond Zhong,‘Hong Kong Officer Fires Shot, and Police Use Water Cannons at Protest’,

The New York Times, 25 August 2019

Note: ‘full gear’, or what might be dubbed ‘riot regalia’, consists of a gas mask (‘pig’s snout’ 豬嘴), goggles 眼罩, face mask 面罩, helmet 頭盔 and an umbrella 雨傘. Ideally the protester will be dressed in black 黑衫.

On 1 September, a planned statute of ‘Lady Liberty’ 香港民主女神像 revealed a figure that would be sculpted in ‘full gear’.]

8 月 25 日荃葵青遊行過後,荃灣二陂坊麻雀館被打碎,大陂坊機舖大閘被撬開;警員奉召到場,一批 full gear 青年用鐵枝、雪榚筒,打碎等候前行警車的玻璃,用鐵枝插傷警車車長背部,混亂中,警員向天打響了反送中運動以來,第一槍實彈。

***

Since, in mid August, the police had employed underground cops disguised as protesters to enable them to arrest people, the militant protesters in Tsuen Wan on 25 August, who themselves had distinguishing insignia, were for a time regarded as ‘ghosts’ [that is, government agent provocateurs]. These popular suspicions were reinforced by the fact that their actions set them clearly apart from even the more overt Courageous-Militant Camp [or ‘Bravehearts’] — that is, they neither merely ‘held the line’ nor ‘retreated’, but employed a strategy of direct confrontation and targeted assaults.

Gradually, the activities of this shadowy group were described in greater detail and discussed online; they came to be recognised as legitimately belonging to the protests. They group came to be dubbed ‘The Dragon Slaying Brigade’.

‘Our organisation launches actions against specific targets. For example, last time (on the 12th of August), when we detected street thugs lying in wait [for protesters] with their weapons in some local shops, we reconnoitered their positions and launched a direct action against them. We don’t think of it as motivated by “revenge” so much as being a way of “striking back” at them [for their previous indiscriminate attacks on people].’

由於月中警方臥底人員混入示威者當中拉人,荃灣連串武鬥派作風的示威者,亦因身上顯著的記認,一度被思疑是「鬼」,因為他們的行動,和所謂的「勇武派」亦有顯著分別,不是「守」和「跑」,而是帶有明確目標的主動攻擊。

到後來,網上開始流傳出這小隊示威者的事,他們被稱為「屠龍小隊」。

「我哋有組織有針對性行動,上次(8 月 12 日),見到班黑社會,係喺嗰幾間舖頭潛伏拎武器,認住個位置,先會有針對性行動,唔好話報復,去打擊返佢哋。」

George (an assumed name) is a twenty-one year old member of ‘The Dragon Slaying Brigade’. He emphasises that the action their group took at Tsuen Wan that night was directed against a police force that is in cahoots with street thugs [or Triad members]. The ‘casus belli’ was the violent attacks by a thuggish mob on protesters by a thuggish mob at Yuen Long on the night of 21 July [which was condoned by the police] and the stabbings that took place at Tsuen Wan on 5 August. In our conversation, George repeatedly avoids words like ‘revenge’ and ‘payback’:

‘Last time around, the police totally ignored the situation when thugs stabbed people on our side. You could say that by initiating our actions we are, in fact, demonstrating to the police how they should really be doing their job responsibly.’

Perhaps not everyone will be comfortable about their actions or see the need to protect The Dragon Slayers. Indeed, within the Anti-Extradition Bill Movement as a whole there is considerable controversy about their tactics.

‘We hope to shock into awareness and incite more people so that they can overcome their psychological hesitation and shift their base-line judgement of just what kinds of action they are willing to accept.’

But, in saying this, does George mean that only by becoming monsters can people effectively respond effectively to the monsters they are protesting against?

‘Our opponents have shown that they have no bottomline, nor do they have any moral qualms about what they are prepared to do. Why should we tie ourselves up in knots with self-imposed limits and moral scruples?’

When discussing the strategic move from employing armed confrontation only to protect protesters against official violence to actively launching head-on attacks, George dismisses the criticisms and doubts raised by others. While he might understand that others who are fighting on the front lines like ‘The Dragon Slayers’ have suspected that they are agent provocateurs he can’t help feeling hurt by their doubts.

‘There are no “Ghosts” among us,’ George states categorically. ‘During our actions on the ground at the time no one doubts our motives, in particular because we always make sure to protect other demonstrators. There is never any doubt which side we are on when we are in direct confrontation with the police.’

‘If you are so concerned or harbour such suspicions, then come out and see for yourself.’

21 歲的 George(化名),是「屠龍小隊」的一員,他表明當日荃灣的行動,針對的是警方和黑幫,起源當然是 721 元朗襲擊以及 85 荃灣刀手斬人,但他一再使用的字眼,都不是「報復」,「上次已經斬傷一個手足,警方都無理,我哋可以話係代警察去執行返個職責。」

但他們的行動和保護,未必人人接受,即使在反送中抗爭中當中亦有爭議,「我哋想喚醒更多人,可以放低內心枷鎖同底線。」那為了對抗怪物,是否就必須變成怪物?「對手已經無底線同道德,點解我哋仲要畀道德同底線鎖住?」

由「以武制暴」到主動攻擊,George 明言他無視外界的批評的質疑,但對於同路人懷疑他們是「鬼」,他既理解亦帶難過,「我哋入面無鬼。」George 回答時斬釘截鐵,「其實現場無人懷疑我哋,因為我哋一路都係保護佢哋,同警察對峙,有喺現場係絕對分到。」

「你真係咁擔心、咁疑心,不如你自己落嚟。」

***

***

George reveals that there are a few dozen people in The Dragon Slaying Brigade. It has a larger membership than that of other small protester groupings that have appeared. What’s different about the Dragon Slayers is that they don’t actually know each other; apart from their actions during protests, they are not in touch on a daily basis. That’s why they need their own secret insignia, ways of identifying themselves to each other.

Their ‘brigade’ came into being by chance. After a black-clad protester was badly wounded in a stabbing incident on 5 August, people at the scene formed a voluntary group to patrol the whole area. They systematically inspected every street and alley in Tsuen Wan. It took all night, but from that patrol involving a voluntary collective The Dragon Slaying Brigade was born.

‘Frankly,’ George explains, ‘no “Ghosts” could have been bothered to spend a whole night out on the streets like that scouring the place for hidden dangers. By that stage, we all knew that we wouldn’t find anything but still we went on the patrol from a sense of duty and responsibility to the protesters. What “Ghost” could be bothered to do that?’

Although the members of The Dragon Slaying Brigade came together by chance and in such adverse circumstances, they actually share quite a lot in common: they are all able-bodied young men. ‘We don’t accept any women’. In fact, the group has actively discouraged women from joining them because, as George explains:

‘Frankly, they would be a burden. Although I very much appreciate their determination and courage, the realities of the situation are such that they really can’t be on the front line.’

Here he touches on a stark reality confronting them: there have been repeated reports of women who have been detained by the police being sexually assaulted. This is proof enough to people like George that if female protesters are arrested they will be confronted with far more vicious punishment than their male colleagues:

‘They strip you naked and subject you to various humiliations. They show no respect for people at all’.

George 透露,「屠龍小隊」成員約數十人,比其他抗爭者的小隊人更多,但成員間彼此互不相識,日常亦不常聯絡,所以在現場必須有明確的識別方法。

而「小隊」的成立更是偶然,8 月 5 日晚,穿黑衣示威者被刀手斬至重傷後,曾有人自發在荃灣守備和巡邏,走遍荃灣大街小巷,一巡就是一個晚上,亦是「屠龍小隊」的雛形,「搜咗成晚,坦白講,鬼係做唔到,你明知搜唔到咩都要去搜。」

「屠龍小隊」成員雖然萍水相逢,但成份卻非常單一:清一色都是年輕力壯的男子,「我哋一個女仔都唔收」,他們甚至「勸退」部分女隊員,「坦白講,(女仔)反而會係負累,我欣賞佢哋決心同勇敢,但現實唔容許佢哋去得咁前。」更讓人難以接受的現實是,接連傳出女示威者被捕後遭性侵的消息後,明確反映女性一旦在抗爭現場被捕,面對的處境恐怕比男性更慘酷,「仲要除晒衫,好侮辱,完全唔 respect。」

***

***

Apart from being the same gender, there’s something else they share in common. Nearly all of them come from broken homes, or they have only tenuous links to their families. George himself is from a single-parent family and he’s been living independently for some time, rarely getting in touch with his former home.

‘People with my kind of background are pretty independent minded, mature and capable. For us family doesn’t factor in to the equation and we don’t feel any particular need for it, though maybe that’s a source of regret.’

‘But that is also why I’m ready to sacrifice myself for what I think of as being my larger family, for Hong Kong itself. This is what we can do; it’s different from all the kids and everyday young men and women [involved in the protests].’

With that George gives a laugh; it’s a laugh that immediately reminds you that this is a very young man who, in many ways, is still on the verge of adulthood. Then you remember that he’s only twenty-one. Meeting him you’d think that he is just like all those other ‘normal young men’ that he’s been speaking about and who he regards as being so different.

‘Anyway, the real grownups have families; they have mortgages to pay, children to support. Our lot don’t have any of those things to worry about.’

Being free of such responsibilities does not mean that young people like George have not made sacrifices. George quit his job to devote himself full time to the protest movement, ‘because I felt a deep sense of shame’, he explains. One time, for example, he missed out on one of those protest film screenings due to a work commitment and the people who attended it were attacked.

‘If I’d been up to me and if I was on the spot, I would have been able to prevent that from happening.’

Does he really have that much confidence in himself?

‘Yeah, I’m in good shape and I’m pretty confident about my martial ability.’

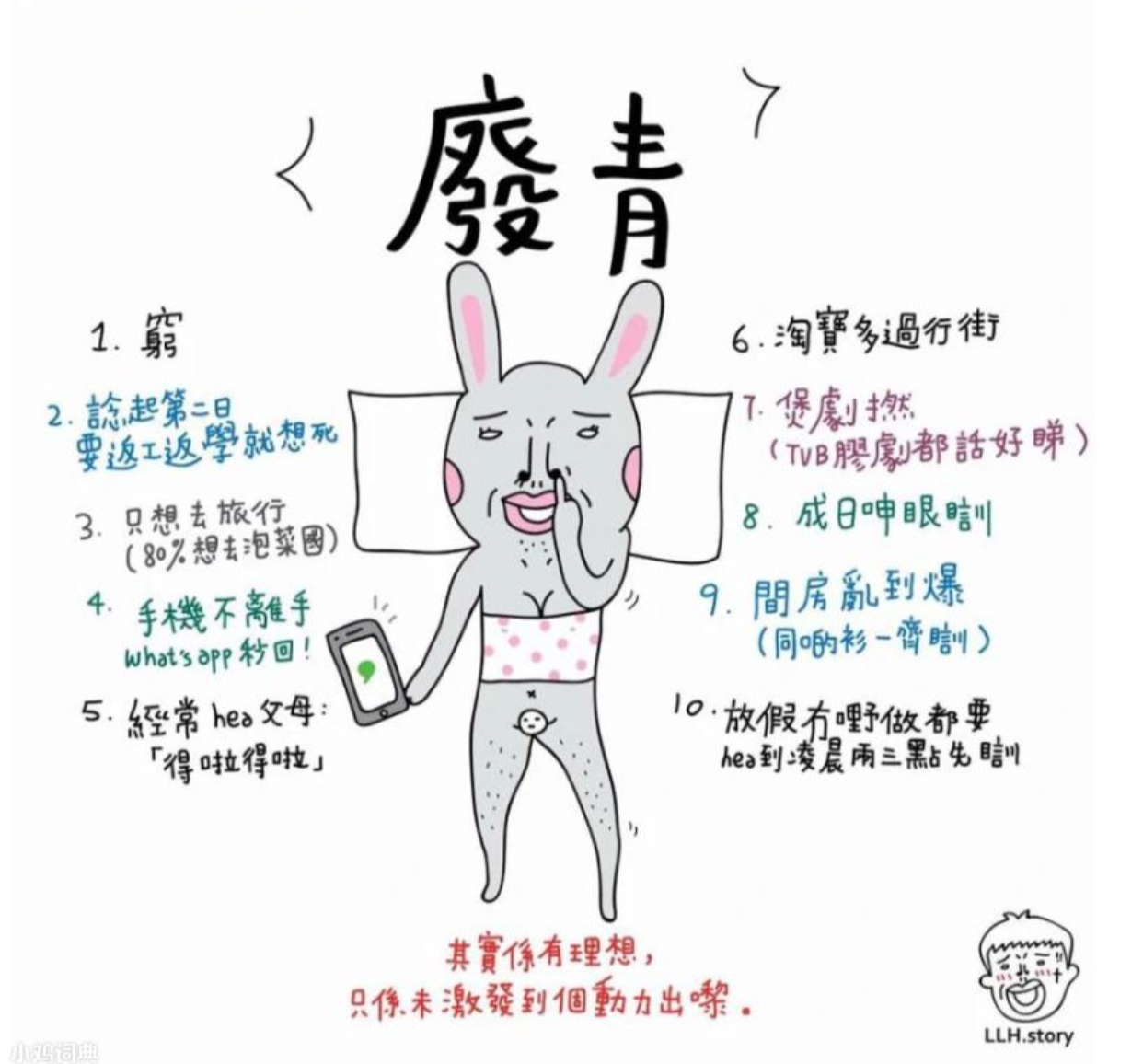

Since becoming a ‘full-time protester’, apart from taking part in violent clashes, George also participates in the kinds of ‘Peaceful Rational Protests’ advocated by moderates that include things as creating Lennon Walls and putting on film screenings. He’s there to help protect others who are participating. In the eyes of many of those who support the police [known as ‘The Blue Ribbon Faction’ 藍絲派] George conforms entirely to the ‘good-for-nothing youth’ stereotype: he’s an unemployed extremist from a broken family who spends his time roaming around Hong Kong taking part in anti-government demonstrations.

‘I had a job that paid HK$30,000 a month. Is that typical of a “good-for-nothing youth”? What crap!’

However, George does share one thing in common with many of the young people who are denigrated as ‘good-for-nothings’ [廢青, or ‘deadbeat youth’, a pejorative term for young protesters used to dismiss the 2014 Umbrella Movement]: like them he has written a will. He gave it for safekeeping to his flatmate, a supporter of the ‘peaceful-rational’ approach to protesting who spends his time watching the action on TV. It’s hard to believe that only two months ago George, now a proud ‘extreme militant’, was himself a member of the peaceful-rational faction and that he supported the moderate approach during such mass demonstrations as those held on the 9th [when one million people took to the streets] and the 12th of June [when police fired rubber bullets and tear gas at protesters].

除了全男班外,這隊抗爭者亦有另一個「特色」,就是幾乎都來自破碎家庭,或者和家人關係本來就薄弱,George 來自單親家庭,早已自立,和家人亦很少聯絡,「我哋呢種人會比較成熟、獨立、識諗,家庭比較可有可無,無咁嘅需要,都有啲 sad 啦咁樣講。」

「亦因為咁,我更願意為香港呢個家犧牲,我哋呢啲有能力唔出嚟,唔通真係交俾班靚仔靚妹咩。」

語畢,George 笑了一下,活脫脫就是一個青澀少年的笑聲,讓人想起他才 21 歲,難道又不是很多人眼中的「靚仔靚妹」?「成年人有家室、有樓要供、有家要養, 我哋呢班人無。」

沒有包袱不代表沒有取捨,George 就為了全心投身抗爭辭去工作,「因為內疚」,例如有一次他因為工作缺席地區放映會,結果參與者遇襲,「如果當初有取捨,就可以阻止呢啲事發生,」這麼有信心?「我對自己戰鬥力、體格都有信心。」

「全職」投身運動的下半場,除了勇武抗爭,「和理非回合」如連儂牆、放映會,他同樣會到場,保護和理非,在不少「藍絲」眼中,激進、無業,來自破碎家庭,每日流連不同抗爭活動,George 就是典型的「死廢青」,「我本身做緊份工,月薪有近 3 萬,係一個廢青做到嘅野咩?亂嗡廿四。」

但有一點是肯定的,就是和很多「死廢青」一樣,走到最前的 George,早已寫好遺書,交予「喺屋企睇電視」的和理非朋友,難以想像,自翊為「極端主戰派」的 George,僅僅兩個多月前,還是一名和理非,69、612 他都在現場,和平地參與示威。

Suspended Animation

Here is the thing about the Hong Kong protesters that’s hardest to convey: to spend time with them is to immerse oneself in a world that is dreamlike, a collective exercise that is almost delusional—that would, indeed, be delusional, except for the fact that the participants are themselves aware that they are suspending disbelief. To many of them, the mainland looms as a place that is both unthinkably powerful and morally inferior; a vast, drab landscape of casual brutality. And yet, despite the fear and loathing, China remains both Hong Kong’s origin and its destiny.

Everyone knows the truth, but few like to dwell on it: Hong Kong is temporarily suspended in a transition between its past as a British colony and its future as a Chinese city that may or may not retain the liberties it now enjoys. This particular scrap of time—a fifty-year stretch built into the handover deal—will expire in 2047. When that date arrives, what will become of all the fights that have absorbed the city’s demonstrators so wholly—the fight against mainland education, mainland justice, mainland identity? The rulers in Beijing will be the ones who answer. …

When you ask the demonstrators about their endgame, they retreat to grandiose fatalism. At least we won’t go down without a fight, they say. History will reflect that we stood up. “In a sense, Hong Kong people are resisting the inevitable: a wave of repression arriving in Hong Kong,” a veteran protester named Johnson Yeung told me. At twenty-seven, he has been arrested five times for his activism. “We’re just trying to turn the doomsday clock back several minutes.”

— from Megan K. Stack, ‘Bravery and Nihilism on the

Streets of Hong Kong’, The New Yorker, 31 August 2019

***

***

It was during that protest on the 12th of June, when tear gas filled the air [police fired over one hundred canisters of tear gas that day] and they all knew that the authorities were adamant in their refusal to respond in any way to the Five Great Appeals being pressed on them by the demonstrators that George felt:

‘It was devastating to see all those people writhing on the ground in agony, gasping for breath.’

‘You Have Taught Us This: Peaceful Protests Are Useless’. It was these words, scrawled on a pillar in the LegCo chamber by the protesters who broke into the building on the 1st of July that left a profound impression on George.

‘Breaking the glass doors of the LegCo like that… so what? People made such a crazy big deal about it. I was among those who became hardline because we knew then that the Peaceful-Rational-Non-violent approach is ineffective.’

Constant escalation is one thing, but all they have as ‘weapons’ are water bottles, umbrellas, then bricks and steel rods. They’ve progressed from self-defense and flight to actively launching sorties and attacks. Will things really go further; with they escalate further from this point?

‘Sure: that’s when the police resort to the widespread use of firearms.’

George doesn’t say it in so many words, but when he says ‘further escalation’, in particular since the events of the 25th of August in Tsuen Wan [with which this article started], we can all pretty much imagine what it means when we say that the situation will escalate even further.

‘In reality right now we are already in armed combat. It’s a battle.’

George knows all too well what that reality means; when the police start firing live ammunition the ‘battle’ will be lost.

‘Sure, but still we must fight. I’d rather be killed now than spend the next dozen or so years in jail.’

But, if there really was a choice, would blood really have to be shed like that?

‘I simply don’t think about all of that. The situation at the moment is that Hong Kong people are fighting Hong Kong people.’

This is indeed the bloody reality of every protest and site of resistance. For instance, among George’s former ‘friends’ there are some members of the police force. ‘They included one guy who was so close he asked me to be a groom at his wedding.’ But, since the outbreak of the Anti-Extradition Bill Protests these old ‘brothers’ have severed all relations.

‘He’s chosen his path. It means that when we next meet it will be on the field of battle. We simply have nothing more to say to each other.’

但 612 他看到的,是漫天紛飛的催淚彈,政府一再拒絕回應訴求,「好慘烈,好多人瞓喺地下典來典去,呼吸唔到,好辛苦。」

「是你教我和平遊行是沒用」,7 月 1 日示威者衝入立法會,這十一隻大字寫在立法會議事廳柱子上,亦早已刻在當日亦有「衝」的 George 心中,「玻璃單野,當時俾人鬧到死,但我哋都一意孤行,因為和理非真係無用」。

升級升級再升級,手中的「武器」由水樽、雨傘,到磚塊鐵枝,由防備逃跑到主動攻擊,還會再升級嗎?「會,例如警方大規模用真槍。」George 沒有明言,他所指的「再升級」的意思,但經歷過 825 荃灣,社會應該大致能想像,激進示威「再升級」的意思。

「而家其實係打緊仗。」但事實上 George 亦心知,一旦警方動用真槍,這場「仗」其實無得打,「係,都係要打,如果要坐十幾年監,我寧願死。」

但若果能選擇的話,真的一定要走到刺刀見紅的地步嗎?

「絕對唔想,而家根本係香港人打香港人。」香港人打香港人,正正是每個抗爭場面,街頭巷尾的血腥現實,例如,George 的「朋友」當中,也有警察,「去到結婚會搵佢做兄弟嗰種」,但自反送中運動以來,曾經的兄弟已割蓆,「佢已經選擇左佢嘅路,大家戰場見,都無必要再同佢講嘢。」

***

Postscript 後記

Prior to my interview, I thought George would probably regale me with a pile of grandiose and extremist statements. After all, among all the demonstrators out there at the moment, The Dragon Slaying Brigade is without doubt the most ‘extreme’ of them all. Moreover, judging from their extremist and violent actions, I had naturally expected to hear things about their contempt and searing hatred for the police.

What George revealed to me, however, was a cool and collected account based on a completely rational analysis of the situation and he presented views that were predicated on an accurate assessment of the evolving nature of the situation. In particular, he repeatedly emphasised that everything that he and the others were doing was their response to the oppressive measures of the government and born out of complete frustration.

All of this was pretty anti-climactic given their rather sensationalist sobriquet — The Dragon Slaying Brigade. It seemed pretty obvious that it was a name that mirrored the Special Tactical Squad (STS) of the police force — known colloquially as the ‘Speedy Dragon Brigade’ [also called ‘The Raptors’, an elite paramilitary group formed by the police in response to the ‘Umbrella Movement’ protests in June 2014]. In reality, nothing was quite so cut and dried.

‘Initially’, George told me, ‘it was all just bullshit bravado. Someone suggested that we call ourselves ‘Truant Fighters’ [inspired by the popular 1991 film Fight Back to School]. But, since the PoPo had their “Speedy Dragons”, we might as well call ourselves The Dragon Slayers.’

It is details like the name that people will remember. In the legalistic terms of Hong Kong’s ‘Crimes Ordinance’, George would be classified as an habitual criminal. In the eyes of the police he would most likely be regarded as a ‘rioter’ pure and simple, that is a ‘cockroach’. But, underneath his ‘armaments’, George and his fellow brigade members are just a group of young men in their early twenties.

‘From day one, I never hoped or wished for casualties. I simply wanted to participate in peaceful demonstrations.’

When George speaks, the words ‘from day one’ are heavily freighted. Maybe that’s how it all started out, this particular summer for this twenty-one year old.

訪問之前,預計聽到的是激昂的陳詞,畢竟,「屠龍」幾近是目前示威者中,最「激」的一群;從他們激烈甚至暴烈的行為,會預期一份對警方切齒的痛恨。

但結果 George 展現的,是冷冷的述說、分析,對事態發展的看法,還一再重覆,這一切都不過是「迫出來」的無奈。

更「反高潮」的,莫過於殺氣騰騰的隊名「屠龍小隊」,看似衝著警方精銳的「速龍小隊」而來,但事實上卻未必是那麼一回事,「其實一開始都係鳩吹,講起隊名,有人提『逃學威龍』,既然警方有速龍,不如叫屠龍。」

也只有在這些末節,會讓人記起,雖然從現行的法律而言,George 是違反刑事罪行的慣犯,在警方眼中,他可能更是不足惜的「暴徒」、「曱甴」,但事實絕下裝備,他和他的「小隊」,都不過是一群 20 出頭的少年。

「有任何人傷亡,都唔係我一開始想見到嘅, 我本來都想和平示威。」從 George 口中說中、聽來異常沉重的「本來」兩個字,或許就總結了,這名 21 歲少年的這一個夏天。

***

Source:

-

專訪:‘勇武派中的武鬥派 名叫「屠龍」的這群人’, 《立場新聞》2019年8月31日

***

The Sound of Silence

What kind of person claims they want to engage in dialogue by first silencing you?

Allow me to invite you to engage in dialogue,

It’s just that I’ll arrest you first and let you rot in jail talking to yourself.

Allow me to invite you to engage in dialogue,

But first I’ll have you dismissed from your job, and without work you will be voiceless. And everyone around you, fearful that they too will be unemployed, will no longer speak out.

Allow me to invite you to engage in dialogue,

But I’ll launch relentless attacks on the online platforms you use for discussions and prevent you from collaborating with your fellows.

Allow me to invite you to engage in dialogue,

But first I’ll stir up the people of the whole country in hysterical response, so no matter where you go you’ll be denounced as a Traitor and they’ll find out where you live so you can be threatened at home.

Allow me to invite you to engage in dialogue,

The thing is, I’ve heard absolutely nothing you’ve been saying out in the streets for the last three months.

Because, even though two million people were in the streets loudly chanting the same slogans, that didn’t count.

Now, around an expertly appointed conference table a number of pro-government plutocrats in their sixties and some ineffectual former bureaucrats gather and reach an amicable understanding. Everything that can and should be said will be said.

True authority is established with the outspoken support of the People.

But, in this environment, you may well claim that you are even-handed when you meting out your punishment. You may well call for everyone to be in dialogue with everyone else and that’s why protesters shouldn’t throw Molotov cocktails any more, and why the police shouldn’t beat up protesters either. Everyone should just go back and sit around your conference table.

But take a good hard look:

Perhaps after all is said and done, all you’ll have at your dialogue is a number of acceptable authorities. You’ll all then take in the sights of our beautiful city beneath and survey its eerily silent streets. For what is left will be all of those people rotting in prison cells going grey.

But, the city scape will indeed be ‘peaceful’, for by then it will be without a sound, without any words, and endless …

有什麼人說要真誠對話,會首先把你滅聲?

請對話

不過我先拘捕你,讓你在牢獄中自言自語請對話

不過我先把你革職,讓你失業也失聲,讓你周邊的人因為害怕無業,不再發言請對話

但我要肆意攻擊你的討論區,讓你不能與同伴合作 請對話 但我要令我整國的人民都激進化,你走到哪裡都會有人說你是漢奸,找你的地址恐嚇請對話

但我對你三個月來在街頭上的說話充耳不聞 因為 街頭上兩百萬人說的話,異口同聲大聲呼叫的口號,沒有效用 但漂亮的談判桌上,幾個六十歲的建制富豪、過氣高官的數句和解,卻是至理名言。威權,總是在人民的歡呼聲中成立的。 你可以在這環境裡,說自己公正持平,各打五十大板。

你可以說每一個人要對話,示威者不要投燃燒彈,警察不要暴打抗爭者,大家走回談判桌。但看清楚,可能說完了這些美麗的說話,談判桌上只有威權的個個領袖,看著美妙的城景,與週遭一片寂靜的街頭。

餘下的,牢獄中漸生白髮,看著城裡的一片「和平」,無聲,無言,無盡…

— from Simon Shen 沈旭暉, ‘Simon’s Glos World’

Facebook, 1 September 2019

***