In modern China (as in so many other countries), changing fashions have reflected the shifting political and cultural landscape of the country. The success of the 1911 Xinhai Revolution not only saw the abdication of the last Chinese emperor, it also ushered in the Zhongshan Suit 中山裝 (known in the international media as the Mao Jacket) designed for the revolutionary leader Sun Yat-sen (Sun Zhongshan), an item of clothing replete with revolutionary symbolism. Although other revolutions led to calls of ‘Off With Their Heads!’, in China the 1911 Revolution did bring about the End of the Queue 辮子, a hairstyle imposed by the throne in the early years of the Qing dynasty nearly three hundred years earlier.

Chinese robes, Manchu fashion, Western suits, revolutionary garb: the clash over styles, ideology and consumerism continues to this day. As early as the Yongzheng 雍正 reign of the Qing dynasty (1723-1735), the ruler felt he had to defend the animal festooned gowns of his officials against charges that they represented barbarian bestiality. Qing court attire was derided by those loyal to the fallen house of the Ming as nothing more than ‘peacock feather caps and horse-hoof sleeved robes: the vestments of birds and beasts’ 孔雀翎馬蹄袖衣冠中禽獸. Yongzheng championed the virtue of Qing rule, and its wardrobe in his Record of Awakening to Righteousness 大義覺迷錄. Two hundred and fifty years later, Chinese Communists and their foreign ideology were decried for being like a Disastrous Flood and Wild Beasts 洪水猛獸. Today the Party and its Chairman of Everything, Xi Jinping, affirm that they rule by virtue 德政; nonetheless, they still walk a cultural tightrope: defending their vision of China on one hand while espousing a heavily edited version of a tradition they originally rejected on the other.

***

In March 2014, President Xi Jinping and China’s First Lady, Peng Liyuan 彭麗媛, embarked on a series of state visits, including to Belgium. Peng, who previously enjoyed a successful career as a singer, is known for her personal style and engaging manner. She was particularly prominent during the couple’s European tour for her wardrobe.

‘First Lady Diplomacy’ and the dress of leaders’ wives have a chequered history in the People’s Republic. Wang Guangmei 王光美, wife of president Liu Shaoqi 劉少奇, attracted considerable attention when she wore a white cheong-sam/qipao and a pearl necklace during a state visit to Indonesia in April 1963. A few years later, she was subjected to cruel parody by Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution and suffered public humiliation by being dressed in a mock cheong-sam and made to wear a necklace made out of ping-pong balls during a mass denunciation rally.

Jiang Qing 江青, Mao Zedong’s wife and paragon of the Cultural Revolution, was known for her austere style of dress. She even had a hand in designing a ‘national costume’ 國服 for women in 1974 to parallel the Mao Jacket.

Peng Liyuan is the first leader’s spouse since Jiang Qing to make a fashion statement and, in the March 2014 trip to Belgium, she appeared in a heavily embroidered traditional- style ensemble. For his part, Xi Jinping wore a reimagined Zhongshan suit, the four pockets of the Mao jacket being replaced by two pockets and a concealed pocket on the chest with a Western-style pocket square. Such forays into Sino-fashion, however, are rare: generally Xi wears a business suit, unless he’s visiting the troops or making some major Party pronouncement in which case he dons revolutionary garb; and Peng Liyuan’s style is more in sync with that of Melania or Ivanka Trump than that of a Ming matriarch (see my ‘Public Appearance’, in Under One Heaven, the introduction to the 2014 China Story Yearbook: Shared Community, p.xv).

The author of the following essay, Kevin Carrico, introduces us to the unsettling world of the Han-Chinese Clothing Movement, one whose adherents feel betrayed by reality. Zealots supporting Han purity have been prominent since the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom civil war of the mid-nineteenth century when the Christian rebels launched racial attacks on the Manchus. Later in the century racist radicals like Zhang Taiyan 章太炎 helped foster a popular hysteria that, in the first decade of the Republic of China, led to bloody anti-Manchu pogroms. Now, a century later, some Han purists even discuss a Final Solution for China’s borderland peoples (extermination, internment camps, exile).

Inspired by the post-June Fourth state-nationalism orchestrated by the Communist Party (something I described at length in To Screw Foreigners is Patriotic in 1995), China Clothing advocates draw their ideas from a miscellany of sources. These include period dramas, Peking opera, kung-fu movies, Hong Kong and Taiwan culture, and so on. They meld paranoia and racism with romanticism; their views are steeped in the political quackery of the party-state, which long ago created an alternate-facts world for China. It is the world of Han supremacists like Zhai Quan’an 翟全安, interviewed in 2008 by the oral historian Sang Ye 桑曄 as part of The Rings of Beijing project.

***

Kevin Carrico is a lecturer in the Department of International Studies (Modern Languages and Cultures) at Macquarie University. He is the author of The Great Han: Race, Nationalism, and Tradition, University of California Press. The following essay was edited to accord with the style of China Heritage and it is published here as a chapter in New Sinology Jottings.

— Geremie R. Barmé,

Editor, China Heritage

24 March 2017

***

Suggested Reading

- Mark Elliott, Hushuo 胡說: The Northern Other and Han Ethnogenesis, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 19 (September 2009)

- James Leibold, In Search of Han: Early Twentieth-century Narratives on Chinese Origins and Development, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 19 (September 2009)

- Tom Mullaney, Introducing Critical Han Studies, China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 19 (September 2009)

A State of Warring Styles

Kevin Carrico

One Picture, Many Thousands of Words

In the autumn of 2001, leaders from across the Asia-Pacific gathered in Shanghai for the annual ministerial meeting of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). It was a month after September 11 and the theme of the gathering was ‘meeting new challenges in the new century’. Organizers and participants could not have guessed that this occasion would give birth to a new Chinese nationalist movement dedicated to meeting new challenges in the new century by seeking recourse to the heritage of the past. This new movement would be called the Han Clothing Movement 漢服運動.

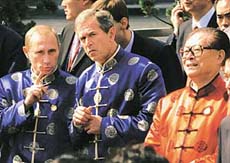

Ever since US President Bill Clinton handed out bomber jackets during the 1993 Seattle Summit, APEC leaders have been obliged to don ‘local dress’ from the host region for cringe-making photo-ops that are supposed to represent the harmony between leaders and nations.[1] In this not so time-honoured fashion, leaders at the 2001 Shanghai meeting gathered, decked out in a traditional-looking Chinoiserie jacket referred to by the hosts as ‘Tang clothing’ 唐裝. Images of US President George W. Bush, China’s party-state leader Jiang Zemin, and Russian President Vladimir Putin engaged in earnest conversation dressed in this mock-Chinese costume posing as a modern-day refraction of traditional Chinese culture soon saturated the official media, the Sinophone Internet and the world wide web.

The ‘Tang clothing’ was presented as some form of traditional Chinese costume (the word ‘Tang’ 唐 has long been used to connote Chineseness among international Chinese communities). But for eagle-eyed observers there was a problem: the APEC Chinese jackets was actually a magua 馬褂 or, in Manchu, an olbo. This form of male Manchu dress was popularised during the Manchu occupation of China from 1644.[2] Ninety years after the fall of the Qing, the denunciation of which was a hallmark of patriotism, Chineseness was being represented on the global stage by the clothes of a former oppressor, a conquest dynasty despised by Chinese patriots throughout the twentieth century for its role in the country’s previous decline and humiliation.

To recast Mao Zedong’s famous line ‘A Spark Can Start a Prairie Fire’ 星星之火可以燎原, the display of Manchu dress, Manfu 滿服, at APEC 2001 provided the spark that started a Han-Chinese prairie fire. According to accounts of the populist sartorial movement emerging in response to that well-intentioned APEC photo-op, a now untraceable post distributed on a number of BBS forums criticised the Chinese government’s decision to dress global leaders in the reviled magua. The author of the post said it would have been far more appropriate for China to promote the traditional style clothing of the Han majority, or Hanfu 漢服. In reality, Hanfu is an invented style of dress that features broad sleeves, flowing robes, belted waists and vibrant colours. Its modern-day proponents claim it was the invention of the mythical Yellow Emperor and was worn for millennia by the Chinese people.

The Han had supposedly long been a relatively restrained and undecorated ethnicity, in contrast to China’s ‘colorful’ singing-and-dancing minorities. Now, the suggestion that they also had ‘traditional clothing’ that could be their own yet again created an online sensation. In the wake of APEC, discussion boards proliferated, the most prominent being www.hanminzu.net. They provided virtual gathering points for patriotic Han Clothing enthusiasts. Soon, devotees had made their own Han Clothing and were posting photos of their handiwork. Shortly thereafter, members of this spontaneous sartorial club were publishing photos of themselves wearing Han Clothing in public.

The most celebrated of these initial Warriors of the Cloth was Wang Letian 王樂天, who uploaded photographs of himself parading through the streets of Zhengzhou in Hanfu. He styled himself heroically under the rubric ‘Grand Aspiration’ 壯志凌雲. It’s a pen name that resonates with the opening line of one of Mao’s most famous late poems (the 1965 poem ‘Reascending Chingkangshan’, released in 1976: 久有凌雲志/重上井岡山, which was something of a call to arms), and it also happens to be the Chinese title of Tom Cruise’s 1986 blockbuster Top Gun. Wang’s ‘maverick’ photographs had a galvanising effect on netizens, and soon people were imitating his grandiloquent performance in cities throughout China. In this process, Han Clothing made the transition from a fantastic invented tradition to a distant image on a screen to a physical reality in the streets of China, in which one could wrap and recognise oneself.

From 2003, Han Clothing associations have sprung up, most particularly in coastal cities, but also in the interior. (Cities with one or more associations include: Shenzhen, Dongguan, Guangzhou, Foshan, Xiamen, Hangzhou, Shanghai, Suzhou, Nanjing, Wuhan, Hefei, Zhengzhou, Jinan, Beijing, Tianjin, Xi’an, Chengdu, Chongqing and Kunming.) These Associations host monthly or fortnightly gatherings, although some enthusiasts meet weekly, eagerly expanding their membership and promoting the movement’s vision of traditional Han culture. Their activities include visits to museums, temples, teahouses, or parks, the reenactment of ‘traditional’ rituals, promotional efforts aimed at greater visibility and the identification of potential converts in crowded downtown areas. They also involve participation in ethnic clothing shows, from which the Han had long been absent, traditional music concerts and self-produced variety shows.

For Han Clothing devotees, the promotion of the eternal apparel of the Han is the most natural of activities, as is the revitalisation of traditional culture more broadly. In my time spent with movement participants, however, I found that despite this focus upon the past, the movement was primarily a product of the present and its contradictions, of which Han Clothing was at once a symptom and an attempted cure.

The Land of Rites and Etiquette

Talking with participants in the Han Clothing Movement, an unabashedly nationalist group, I had at first expected to hear more of the usual talk about the unique glory of China with which I had long been familiar. Yet for a group dedicated to celebrating the idea of China, the sheer amount of time that participants spent complaining about contemporary China was surprising.

At a gathering in a Shenzhen restaurant in 2010, a Han Clothing enthusiast from rural Anhui who was in his late twenties asked: ‘How much do you know about traditional Chinese culture?’ It was a rhetorical question: he immediately highlighted for me four components of tradition, namely clothing, food, housing and transport 衣食住行. He assured me that these were the core of Han, and thus Chinese, traditional culture.

In the dynastic era, he opined, ‘clothing’ 衣 was elaborate and beautiful. Proper attire was a central, ordering component of society. Establishing a metaphorical relationship between the individual body and the social body, he said: only when clothing was in proper order could society be put in order. But nowadays, he sighed, the Chinese don Western-style apparel made from synthetic fibres. Men wear sneakers and Western suits that never quite fit their bodies, and women, he asserted, walk around exposing their breasts and buttocks; it’s in violation of appropriate dress codes and an affront to national dignity. This Han Clothing gathering, he assured me, would allow me to finally see authentic ‘Eastern clothes’.

Another core component of Chinese culture, he continued, is ‘eating’ 食. Chinese cuisine is rich and diverse, extending from the delicate cuisine of Shanghai to the numbing spice of Sichuan and down to the refined gastronomy of Guangdong. And throughout history, the social experience of sharing a meal has created lasting bonds between people. Yet, he quickly added, nowadays food is not always safe; you have to be careful of what you eat. There is the infamous gutter oil 地溝油 (unclean cooking oil that is endlessly recycled in restaurants), genetically modified foods and even fake eggs. ‘Fake eggs might look better than real eggs,’ he said, ‘but below the surface they’re made of cancer-causing agents.’ We stared at the dishes before us, which had long before grown cold.

Under the rubric of ‘living’ 住, my interlocutor affirmed traditional architecture: ‘nowadays, we think that we are more advanced than the ancients. But in many ways, they were much smarter, and had answers to many questions that are now lost.’ Citing the canals supposedly created by the legendary Yu the Great 大禹 to control flooding of the Yellow River, he told me with a look of certainty that these canals and riverbeds remain strong to this day. Pointing to the skyscrapers outside, he asked: ‘How long do you think those buildings will last? These days, apartments start falling apart long before you’ve even paid off your loan.’

With a sigh, he told me ‘the China out there, the China that you are visiting, that is absolutely not the real China’ 不是真正的中國. In that moment, I was left to make sense of a member of a nationalist group telling me that his nation was not, in its current form at least, real. This confounding situation, in my analysis, revealed the fundamentally paradoxical core of the Han Clothing Movement and the nationalist experience that it represents. Beyond bland descriptions of nations as imagined communities passing through ‘homogeneous, empty time’,[3] or the not particularly adrenaline-charged idea that ‘the political and national unit should be congruent’,[4] for the nationalist nations are far more exhilarating. They are imaginary communities that embody one’s greatest aspirations. Yet as a result, as highlighted in this monologue, nations are also freighted with one’s greatest disappointments.

Such dissonance is also evident in the discourse surrounding the ‘Rise of China’. The revitalization 復興 of China is based on the idea-cum-belief that the nation should recapture a presumed preeminent place of respect and reverence in the global hierarchy. On the quotidian and human level, however, the rise of China is accompanied by rising social tensions, pollution indices, living costs, crime rates, health risks and general social anomie. The nation as an experienced geographical space is trapped at an untraversable distance from the nation as fantasy: the ‘land of rites and etiquette’ 禮儀之邦.

An Ongoing Xinhai Revolution

Academic debates over the history of race and essentialism in China are of little interest to Han Clothing enthusiasts; they are participants in a popular racial-nationalist movement. Within their worldview, ‘Han’ is a biological and racial category whose purity was maintained throughout the dynastic era via a distinction between civilisation and barbarism. When I attempted to dig a little deeper on this question of purity, participants would acknowledge that there may have been intermarriage between the civilised peoples of China’s Central Plain and invading barbarians, but it was only ever intermarriage between Han males and barbarian women — no civilised Han woman would have ever married a barbarian male. According to this narrative, the imagined dominance of male chromosomes, based on patrilineal cultural assumptions, meant that Han male DNA would erase any trace of female barbarian miscegenation within three generations. Han purity is always victorious.

In movement histories, this seemingly invincible purity suffers a radical break in China’s late-dynastic period. First there is the rise of what is denigrated as the ‘Mongolian-Yuan’ dynasty (1271-1368), which Han Clothing zealots characterise as being non-Chinese, flying in the face of the carefully crafted party-state narrative of a unified Chinese history. Although the Yuan aberration was corrected by the rise of the Han-led Ming dynasty (1368-1644), the Ming eventually fell to another invader barbarian race, the Manchus. The Qing dynasty (1644-1912), according to Han Clothing Movement advocates, was the first extended campaign in a racial war that continues to this day.

‘If you hand the Mandate of Heaven over to a bunch of barbarians,’ one participant commented, ‘what do you expect to happen?’ Han Clothing Movement narratives portray the Manchu rulers of the Qing as single-mindedly dedicated to the destruction of the Han and thus of China itself. The real violence, for example, of the Ten Days in Yangzhou 揚州十日, during which a Manchu-led massacre devastated the city of Yangzhou, or the queue edict issued by the Manchu court imposing a particular hairstyle on Manchu and Han males alike, is combined with imaginary violence of the forcible erasure of Han Clothing.[5] Through such violence, it is asserted, the Manchus fundamentally transformed Chinese society, making it into an Other of itself, and thereby shifting its essence from civilisation to barbarism. Today, Han Clothing devotees claim that such ‘uncivilised practices’ as spitting, line cutting, forcing others to drink alcohol, or corruption are the product of the Manchu taint. Thereby an historical ‘amnesty’ is declared exonerating Han people from complicity and responsibly for the state of contemporary China, a state that Hanfu enthusiasts reject.

This convenient historical amnesty keeps alive the fantasy of an eternal ‘true Han society’, one that is completely different from the present, and that can be best be realised through the programme of the Han Clothing Movement. Against the never-ending violence of the Manchus, movement participants posit a narrative of equally unyielding Han resistance: a permanent Xinhai Revolution. While 1911 was a political Xinhai Revolution 辛亥革命 that led directly to the fall of hated Manchu-Qing rule, 1945 and 1949 are characterised as military Xinhai Revolutions. The Cultural Revolution of the 1960s, in turn, is reinterpreted as a Cultural Xinhai Revolution, targeting not traditional Chinese culture, but rather insidious Manchu culture. This narrative of the ceaseless Xinhai allows movement participants to cherish their idea of traditional culture while also continuing to idolise Mao Zedong: his drive to sweep away tradition in 1966 by ‘Smashing the Four Olds’ 破四舊, for example, was in reality the work of a cunning and clandestine anti-Manchu warrior.

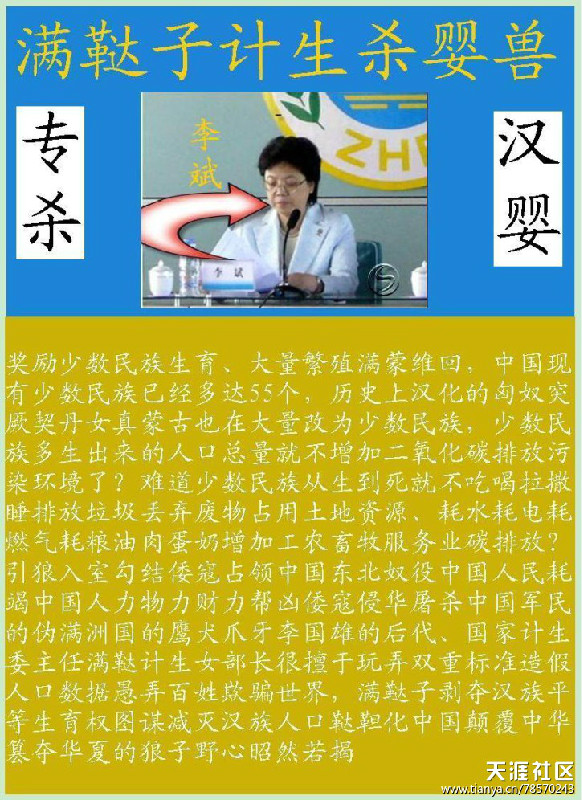

After seven decades of permanent Xinhai revolutions, however, movement participants argue that there is still a dangerous conspiracy in contemporary China; it is a secret Manchu plan for restoration that has been underway from the start of the post-1978 reform era. In meticulously documented conspiracy theory tracts traded online and shared in group meetings, Han Clothing Movement zealots argue that Manchus secretly control every important party-state institution: the People’s Liberation Army, the Party Propaganda Department, as well as the Ministry of Culture. The secretive nature of organisations like the Han Clothing Movement itself, makes them an ideal hotbed for such conspiracy theories. Denials that a certain official may in fact have a Manchu heritage, furthermore, is viewed as veiled confirmation of just such a heritage. This ensures that conspiracy theorists can detect surreptitious Manchu aggressors anywhere and everywhere.

The State Family Planning and Population Commission, for instance, is regarded as a stronghold of Manchu influence. It is believed that its one-child policy is but an escalation of the long-term Manchu genocide that targets the Han. After all, as movement participants asked me on numerous occasions: ‘Does this [the one-child policy] seem like something that one race would do to its own people?’

Re-creating Real China

The name Han Clothing Movement, Hanfu yundong 漢服運動, encapsulates the movement’s response to the dilemmas of life today. Hanfu or ‘Han Clothing’, purportedly a sartorial code passed down through the ages from the time of the Yellow Emperor, provides a seemingly concrete link to a distant yet also more genuine past. Its revival reintroduces lost grandeur and aesthetics into the dreary and distressing present. Yundong, by contrast, is a term derived from the Maoist vocabulary of political mobilisation. Here, rather than the countryside surrounding the city 農村包圍城市, the movement promotes a sacred tradition surrounding profane reality, declaring an aestheticised warfare on the dictatorship of the real.

Editorial Update

On 15 March 2017, to great online fanfare Zhou Xiaoping 周小平, a man derided in the non-official media as party-state leader Xi Jinping’s Internet courtier (in October 2014, Xi had extolled Wang’s online logorrhoea as representing pro-Party ‘positive energy’ 正能量), announced his marriage to Wang Fang 王芳, a popular songstress known for cloying renditions of revolutionary songs 紅歌. The nuptials featured a pastiche ceremony and pictures emerged of the couple swaddled in Hanfu costume.

Zhou proudly announced to his new bride (and to any media outlet that gave a damn): ‘My body belongs to the State, but my heart is yours!’ 身許國家,心許你.

For more on Zhou Xiaoping, see Zhang Lifan 章立凡, Every Emperor Needs Slavish Courtiers 每一个皇帝都需要奴才, 28 November 2014, for the English version in the New York Times Sinosphere blog, see here.

My thanks to Sang Ye for alerting me to the Zhou-Wang alliance.

In April 2018, David Bandurski of China Media Project reported on ‘Sunshine Boy’ 暖男 Zhou’s fall from grace. This seems to have been occasioned by the ouster of his patron, Lu Wei 魯煒, the head of the Cyberspace Administration of China who had been arrested on charges of corruption. See David Bandurski, Sunset for China’s ‘Sunshine Boy’, China Media Project, 5 April 2018.

Notes

[1] A series of photographs illustrating the history of this politico-sartorial practice can be found at APEC Summits: what the leaders wore — in pictures. This APEC tradition was abandoned at the 2011 APEC summit in Hawai’i. According to US President Barack Obama’s reflections on aloha shirts and APEC:

I got rid of the Hawaiian shirts because I looked at pictures of some of the previous APEC meetings and some of the garb that appeared previously and I thought this might be a tradition that we might want to break.

See Adam Taylor, APEC’s silly shirts: the awkward tradition that won’t go away, Washington Post, 10 November 2014.

[2] Hazel Clark, The Cheongsam, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

[3] Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London: Verso, 1983.

[4] Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1983.

[5] Edward J.M. Rhoads, tracing sartorial policy in the Qing Dynasty, notes that the adoption of Manchu clothing was only required of the male scholar-official elite: ‘the great majority of Han men were free to continue to dress as they had during the Ming,’ as were women. Although historically inaccurate, the movement narrative of the forced suppression of Hanfu in the early Qing conveniently helps to explain the current unfamiliarity with this invented tradition. See Edward Rhoads, Manchus and Han: Ethnic Relations and Political Power in Late Qing and Early Republican China, 1861-1928, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2000, pp.61-62.