International Children’s Day 國際兒童節, which is marked on various dates around the globe, was first declared as a national holiday in Turkey in 1929, although it had been celebrated from 1923 following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and the founding of a modernising secular state. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk made children part of the effort of national reconstruction, just as they were to be lionised and used in various Europe nations and in Asia.

Although the origins of the day reach back to Christian America in the nineteenth century, a special day set aside to adulate children, their care, their protection, and even their service to the state, is a thing of the twentieth century. As ‘childhood’ became a category in the social sciences, family planning, culture and gendered discourse in the modern nation-state, it was also ‘weaponised’ by regimes around the world. For its part, from 1931, the Chinese Republican government marked Children’s Day on the 4th of April, and it is still celebrated on that day in Taiwan/ The Republic of China.

***

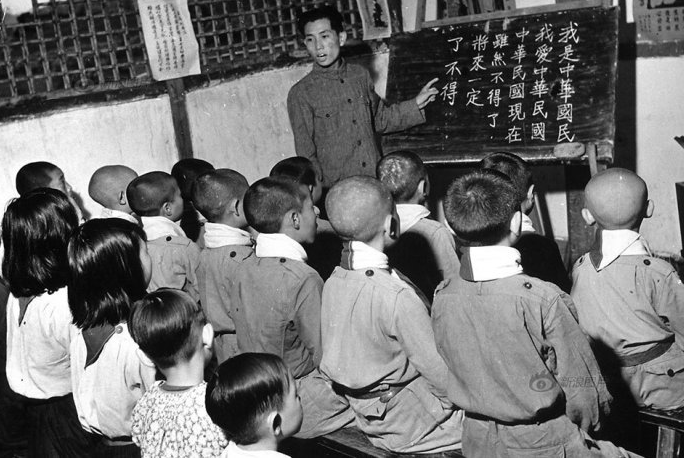

The political struggle for children has a long history in modern China, and it is one inextricably bound up with the New Culture Movement that marks its centenary this year. The education of the young, establishing new ethics, attitudes towards local and global culture, and the inculcation of a modern worldview were issues at the heart of both Chinese revolutions, republican and communist. In the 1910s the struggle was partly over the Confucian tradition and its place in Chinese life and, from as early as the 1920s, educators and parents were unsettled that the dominant Nationalist Party imposed its propaganda messages on schools, as well as local and national curricula.

Those who opposed such indoctrination looked to international and traditional exemplars in their advocacy of protecting ‘the childlike heart’ 童心, in children and in adults alike. The childlike heart, a concept known from the time of Mencius, featured in the writings of Li Zhi (李贄, 1527-1602), the late-Ming iconoclastic philosopher. Li’s ideas were now praised by writers like Lin Yutang 林語堂 and reflected in the essays and art of like Feng Zikai 豐子愷, both of whom frequently feature in China Heritage.

As Li Zhi wrote (in Lin Yutang’s translation):

The child is the chrysalis of the man; the childlike heart is the original state of mind. Yet how does it come about that the original state of the mind, the childlike heart, can be lost? It starts when one sees and hears things that come to rule over the mind. When growing up, one is told about and shown various principles which come to hold sway, and thus is the childlike heart lost. With the passing of time one sees and hears more of the principles [of the world] and one’s knowledge increases daily… . These principles take the place of one’s heart and what one says is nothing but [a repetition] of these principles; they do not issue from one’s childlike heart. No matter how clever one’s words may be they are not sincere, and so it is that false men speak falsehoods, do false things and write false words. As soon as a person has thus falsified themselves, will not everyone they do in turn be false?

In a review recommend the linguist Yuanren Chao’s 趙元任 accomplished translation of Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the essayist and translator Zhou Zuoren 周作人 observed that:

Too many adults have lost entirely their childlike heart. It is as though the caterpillar, having turned into a butterfly, has absolutely nothing to do with its former self. this is a very sorry state of affairs. They have forgotten what it is like to be a child; not only are they incapable of appreciating the sensibilities of children — they lack any desire to nurture or protect their children and instead end up doing them harm.

— both quotes are from my An Artistic Exile: a life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975), pp.139 & 142.

***

Children as the harbingers of the future have been and remain a crucial aspect of Chinese Communist propaganda which, in its early decades, was profoundly influenced by the Soviet Union and its inculcation of young successors to the revolutionary cause (see, for example, the swearing-in ceremony for Soviet Young Pioneers here). For Official China the cult of childhood, service, sacrifice and martyrdom remains central to the celebration of children. The groundwork for this was laid in the Communist base at Yan’an and in the areas under Party control during the Sino-Japanese conflict. Children were part of the revolutionary vanguard of the war and they would feature as agents for Party change in the People’s Republic after 1949. From 1950, Child’s Day was to be celebrated on 1 June and this day has marked International Children’s Day in China ever since.

Be it during the initial phase of China’s socialist construction, through the heyday of High Maoism in the Cultural Revolution, as part of the educational transformation of the country during the Reform era, in the post-June 1989 indoctrination campaigns, or as part of the consumerist frenzy of recent decades, China’s children have been and remain on the front line. Once they were encouraged to report class enemies; today they are still encouraged to keep an eye out for enemy agents, as well as to resist the blandishments of ‘the West’. It is little wonder then that in the past parents with the means to do so withdrew their children from the Party-controlled education system (for example, see Sang Ye, 1949-2009: Sixty Years Out of Range, in The Rings of Beijing), or that today those with the money send their children to international schools in China, or to be educated overseas.

***

Over the months, New Sinology Jottings have focussed on traditional and revived Chinese calendrical festivals. Today, we mark the significance of International Children’s Day in China by presenting a video work by the Beijing-based artist Andrea Cavazzuti below. (See Andrea’s Stories of Regret — the Zhang Family of Huayin, which also features the artist’s biography.)

We conclude this audio-visual celebration with a translation of one of the best-known essays from late-Qing China, ‘A Pavilion for Sick Plum Trees’ by Gong Zizhen.

We will return to the topic of children, horticulture and politics on the 4th of June.

— Geremie R. Barmé, Editor, China Heritage

1st June 2017, International Children’s Day

國際兒童節

***

Fictional Kids

a video by Andrea Cavazzuti*

I started taking photographs in earnest in the late 1970s and continued to do so in China from when I moved there in the early 1980s. In 1994, I began making videos, an artistic format which I particularly liked as I thought it could best reflect my passion for images, literature and music. The videos I made were fairly much in the style of my previous photographic work: filming whatever attracted my attention or whatever I thought I might be able to turn into something interesting. No pre-ordained plot or script, just some happenstance clues and only the vaguest idea of an overall project: China.

When, in 1999, I decided to devote myself to video, I went through the huge amount of footage I had accumulated and was immediately struck by something: without realising it I had quite a collection of material on children playing in the streets. Back then kids were everywhere, enjoying unfettered moments outside.

When I was a kid in the 1960s we spent most of our free time playing in the street. There were no grown ups around telling us what to do, or interfering in our games, let alone to play with us. We were left entirely to our own devices, unless we did something that attracted attention and led to a scolding or being chased. Or, if we’d been kicking a soccer ball against a shop window despite repeated warnings and the owner managed to get a hold of our ball to slash it.

China in the 1990s was about the same. I was probably drawn to making all that footage because, although I was now an adult, I felt that I was witnessing scenes from my own childhood. I decided to edit the material into something like a visual poem, though I had no idea how to do it. I worked on it for ages, experimenting with various combinations of images and music until finally, one day, something occurred to me. I realised that I’d filmed scenes that evoked my own experiences (such is the lurking ‘autobiographical impulse’ of so much that we do), but my experiences were surely tainted by my culture, the books I had read and, most of all, by the movies I had watched. So, I thought to myself, why not push this interaction between reality, memory and fiction even further; why not create a melange: East and West, fiction and reality, memory and imagination, the past and the present?

I made a selection of soundtracks from well-known Western movies and combined them with the footage I had. Slowly, magically, things started falling into place. A vision, part reality, part imagination, started to take shape: the world of childhood clashing, interwoven or orchestrated with music, a movie of childhood, for adults. After that, the editing progressed smoothly.

My friend Carlo Laurenti saw a rough cut of the material and suggested I introduce it with an apocryphal story about Confucius encountering children during his peripatetic travels.**

This is the genesis of ‘Bambini’, or ‘Fictional Kids’:

* Author’s Note: My thanks to Geremie Barmé for his extensive editorial suggestions.

** Editor’s Note: The obstreperous young boy Confucius is said to have encountered was Xiang Tuo 向橐.

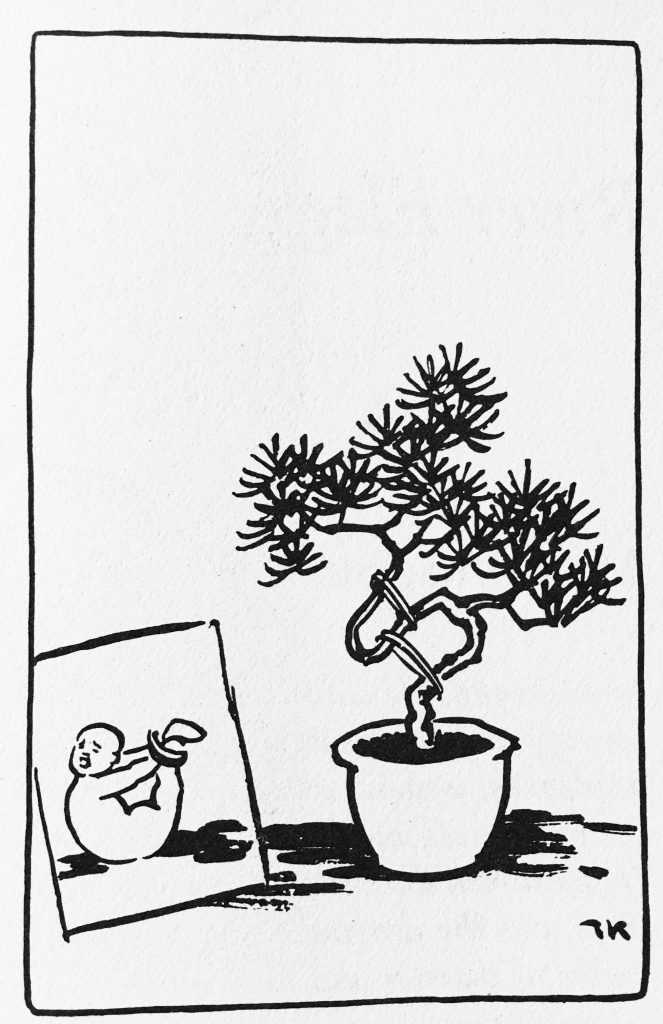

A Pavilion for Sick Plum Trees 病梅館記

Gong Zizhen 龔自珍 (1792-1841)

Longpan in Jiangsu, Dengwei in Suzhou and Xixi in Hangzhou are known for their fine plum trees. It is the accepted wisdom that the plum is at its most beautiful when its branches grow in writhen forms; for to be straight is to be graceless. The beauty and spirit of the plum manifest themselves only when the tree grows at an angle and when its branches are sparse; this is unquestioned. 江寧之龍蟠,蘇州之鄧尉,杭州之西溪,皆產梅。或曰:梅以曲為美,直則無姿;以欹為美,正則無景;以疏為美,密則無態。固也。

Yet these requisite virtues of the plum are, in fact, no more than the fancy of scholar-painters. Naturally, it is not for them to demand publicly that all plum trees be cultivated in such a fashion; nor have they been able to impose their will so that all plums are maltreated, crippled, and savaged. After all, the common man has not the cunning to fashion plums in such a manner for profit. 此文人畫士,心知其意,未可明詔大號以繩天下之梅也;又不可以使天下之民斫直,刪密,鋤正,以夭梅病梅為業以求錢也。

Still, there are those who have told nursery owners of the clandestine passion of the scholars, and thus it has come about that gardeners will cut off the hale and straight branches of the plum, encouraging deformed and twisted limbs in their place. They have cropped the thick foliage and growth of the trees, killing their tender sprays and shoots. they have crippled the life force of the plums so they may be sold for large sums. Now the plums throughout Jiangsu and Zhejiang are mutilated and sickly — such is the devastation wrought by the literati! 梅之欹之疏之曲,又非蠢蠢求錢之民能以其智力為也。有以文人畫士孤癖之隱明告鬻梅者,斫其正,養其旁條,刪其密,夭其稚枝,鋤其直,遏其生氣,以求重價,而江浙之梅皆病。文人畫士之禍之烈至此哉。

I bought three hundred plums in pots, and not one of them was whole. For many days I felt ill at heart, then I swore to cure them. I released them from their bondage, planting them in the earth, smashing their pots so they may grow as nature dictates. I will spend the next five years nursing these trees back to health; and, as I have never regarded myself as one of their number, I am prepared to suffer the derision of the scholar-painters for building my Pavilion for Sick Plums. 予購三百盆,皆病者,無一完者。既泣之三日,乃誓療之:縱之順之,毀其盆,悉埋於地,解其棕縛;以五年為期,必復之全之。予本非文人畫士,甘受詬厲,辟病梅之館以貯之。

Sad indeed is the fate of the plum! If only I had more time and land, I would devote my remaining days to the plums of Jiangsu, Suzhou and Hangzhou. 嗚呼。安得使予多暇日,又多閒田,以廣貯江寧、杭州、蘇州之病梅,窮予生之光陰以療梅也哉。

— trans. Geremie Barmé, with Linda Jaivin,

New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Rebel Voices, 1992, p.136.