Watching China Watching (XVII)

China Watching has never merely been the province of outsiders. As we have pointed out previously in Watching China Watching, those who watch, analyse and critique China with the greatest intensity are themselves often part of the Chinese, or Sinophone world. Again, as we have noted before, to watch China, one also needs to know how to listen, and to read.

Below we offer an analysis of the Chinese socio-political condition by a leading scholar — and sometime political adviser — whose ideas about the continuities between traditional and modern China have made him famous, and controversial.

Jin Guantao 金觀濤, collaborating with his fellow academic and wife, Liu Qingfeng 劉青峰, formulated the concept of China’s socio-political world as being an ‘ultrastable system’ 超穩定結構 in the 1980s. In the following essay, Jin addresses the question of China not as an being unchanging, eternal empire, but rather as being a complex structure that melds the ideological, social and political in ways that tend to sustain long-term stability. Regardless of the odeur surrounding orientalism, for Jin the issue of China’s resilient dynastic system — and its reconfiguration under the ideological, political and military hegemony of the Chinese Communist Party — raises questions long thought by superficial analysts, or those pursuing a crude globalism, to be obsolete, or at least unfashionable.

Under Xi Jinping, many students of China may well find it necessary to revisit issues, ideas, tropes and theories that were thought to be otiose due to the grand economic changes wrought in the People’s Republic. Those who have observed the party-state’s recalibration of its ideas and modus operandi in the context of change, may find the past very much alive in the present. In Jin Guantao’s essay we offer one particularly insightful perspective on the problem.

Other thinkers, like Dingxin Zhao, disagree with the Jin-Liu analysis and propose that pre-modern China was a Confucian-Legalist state, one that arguably has found a new incarnation in the twenty-first century. In a review of Zhao’s work the historian Peter Bol remarks that the book:

is a strong defense of the liberal position in China today against those scholars and politicians who claim that China’s future can be positively related to its past. The Confucian-Legalist State: A New Theory of Chinese History can be read as a warning, although not stated so explicitly, against the restoration of the Confucian-Legalist state whose values the author implies still linger in the Chinese mentality but contravene human nature.

— The American Historical Review

vol.122, no.2 (1 April 2017): 499

Although Jin Guantao ends his essay by positing, hopefully, that without thoroughgoing political reform China’s systemic crises will continue, he also makes the case that the country’s ‘deep structure’ is reflected in ‘the integrative tendency 一體化 of moral ideology and social organization in China.’ He says that:

When this form of organizational system exists in isolation from the rest of the world and has yet to encounter foreign challenges, its distinguishing feature is the cyclic rise and fall of dynasties, all of which were founded on the goal of achieving great unity 大一統. But with the challenge of the West, the system behaved differently, and the shift that it underwent could be expressed paradigmatically as “the disintegration of the traditional integrative structure—the replacement of the old ideology by the new—the establishment of a new integrative structure.”

Over the years, the Chinese Communist party-state would seem to be (or, rather, has worked hard to become) just such an integrative structure, one that that combines moral ideology with military-police might and social organisation. In the argument below, Jin follows the milestones of modern Chinese history to make his case. For those who watch China today, this history, and familiarity with it (and the debates that surround it) remain important: it is not only part of the various narratives employed in the Official China Story, it also plays a crucial role in the way the Chinese state articulates a vision for the future, in particular in the form of the Two Centennials 兩個一百年 promoted with particular enthusiasm since Xi Jinping’s accession to party-state-army power from 2012.

***

Jin Guantao’s essay is reproduced with the kind permission of Gloria Davies, who translated it for the edited volume Voicing Concerns: Contemporary Chinese Critical Inquiry (2001). Minor emendations have been made to the text, and Chinese characters have been added where necessary.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

6 February 2018

***

Further Reading:

- Watching China Watching, China Heritage, 5 January 2018-

- Gloria Davies, ed., Voicing Concerns: Contemporary Chinese Critical Inquiry, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2001

- G.R. Barmé and Sang Ye, A Beijing That Isn’t (Part I), China Heritage Quarterly, Issue 14 (June 2008)

- Gloria Davies, Worrying about China: The Language of Chinese Critical Inquiry, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2009

- Thinking China, The China Story, 2012-

- The Practice of History and China Today, The China Story, 15 August 2015

- Dingxin Zhao, The Confucian-Legalist State: A New Theory of Chinese History, New York: Oxford University Press, 2015

- Reading and Writing the Chinese Dream: introducing a project, The China Story, 16 January 2016; and, China Dream UBC

- Ideas and ideologies competing for China’s political future, Mercator Institute for China Studies, 5 October 2017

Modern Chinese History and the

Ultrastable System

Jin Guantao 金觀濤

- Introduction

- The Unity of Premodern and Modern Chinese History

- The First Surge of Modernization: The Self-Strengthening Movement and Qing Reform Policies

- The Rupture of Chinese Social Organization

- Why Have Attempts at Democracy Failed?

- The Role of the New Culture Movement

- The Politics of Ideology and the Reconstruction of Chinese Society

- Successes and Failures of the KMT

- Reasons for the Rise of the Chinese Communist Party

- A Historical Perspective

Introduction

After June Fourth 1989, the rewriting of modern Chinese history became an important new trend in Chinese intellectual circles. Chinese intellectuals could no longer be satisfied with the official explanation of “anti-imperialism and antifeudalism” as the guiding thread of modern Chinese history. Equally, they were unable to fully identify with Western scholarship on China’s “response to the Western challenge” or with Western understandings of “modernization” and “imperialism.” They sought instead to understand changes within modern Chinese society by means of a China-centered approach. The book I coauthored with Liu Qingfeng entitled The Transformation of Chinese Society (1840–1956): The Fate of Its Ultrastable Structure in Modern Times 開放中的變遷——再論中國社會超穩定結構, published by the Chinese University of Hong Kong Press in December 1993, is an example of this new investigative approach.

By means of a theory of ultrastable systems, this book offers a new explanation of the modern and recent stages of China’s history. What distinguishes this explanation from others is that it allows for the integration of China’s premodern history with its modern history by arguing for the existence of an organizational deep structure within Chinese society.[1] This deep structure has shaped both premodern and modern China and has remained unchanged for 2000 years. This deep structure is none other than the integrative tendency 一体化[2] of moral ideology and social organization in China. When this form of organizational system exists in isolation from the rest of the world and has yet to encounter foreign challenges, its distinguishing feature is the cyclic rise and fall of dynasties, all of which were founded on the goal of achieving great unity 大一统. But with the challenge of the West, the system behaved differently, and the shift that it underwent could be expressed paradigmatically as “the disintegration of the traditional integrative structure—the replacement of the old ideology by the new—the establishment of a new integrative structure.” We use this to summarize the main course of change in modern Chinese society from the disintegration of empire during the late-Qing era to the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) rise to power. Our treatise on ultrastable systems attempts to locate and determine the structural connections by which the Self-Strengthening Movement, the 1898 Hundred Day Reform, the 1911 Revolution, the New Culture Movement, the Nationalist Party, and the CCP became guiding forces in Chinese society. This essay is drawn from the argument Liu and I put forward in The Transformation of Chinese Society (1840–1956): The Fate of Its Ultrastable Structure in Modern Times.

The Unity of Premodern and Modern Chinese History

China’s ability to realize the grandeur of imperial unity as early as the Qin and Han dynasties is due first and foremost to the implementation of a system whereby intellectuals, unified in their way of thinking under Confucianism, were selected for office within the imperial bureaucracy. For example, during the Qing dynasty, all educated men were required to take part in the county examinations from which 25,000 xiucai 秀才 (first degree holders) were selected each time. During the provincial examinations that were held every three years, 1,200 juren 舉人 (second degree holders) were picked from among the xiucai. Of these, 600 were able to obtain official positions. Three years later, the juren were required to sit for the metropolitan examinations and 200 or 300 jinshi 進士 (third degree holders) were then selected from the juren candidates.[3] The intellectuals selected by this imperial examination process thus formed a unified bureaucratic organization.From the time of the Qin and Han dynasties to the Qing epoch, a period of some two thousand years, the size of the bureaucracy did not remain constant, varying from smaller bureaucracies that were made up of officials in the tens of thousands to larger bureaucracies that had over 100 thousand officials.[4] The Qing bureaucracy, for instance, comprised some twenty thousand officials. The imperial examination system was able to obviate problems arising from regional separatism as well as attempts at political monopoly on the part of the aristocracy. Thus the form of government in imperial China was a fairly rational one and provided the means for achieving order and integration in a vast agricultural society. However, relying solely on the services of tens of thousands of bureaucrats is evidently not sufficient to govern a country like China, which extends over such a vast area and has a huge population.The number of officials in the Qing bureaucracy represented no more than a very small fraction of the overall population at the time. At best, it formed no more than the upper stratum within the overall social organizational framework. Like that of its historical predecessors, the administrative capacity of the Qing government extended only to the county level. On average there were five officials per county assigned to the task of governing an area with a population of some 250 thousand.[5]

To cope with the difficulties of administration, the imperial Chinese government relied on the cooperation of the local gentry in order to extend the functions of government. This practice constituted the self-government of the lower stratum from the county level downward. Because many of the local gentry were former government officials living in retirement, they too were intellectuals who believed in Confucian culture, and the majority of these played the three key roles of being members of the local elite, patriarchs of their lineages, and landlords simultaneously. They governed the countryside by means of their individual prestige and wealth, collecting taxes and recruiting soldiers on the government’s behalf while engaging in local charitable activities and communal projects. During the Qing dynasty, there were about 1,400,000 members of the gentry class who made up 0.3 percent of the total Chinese population.[6] This group, which was many times the size of the imperial bureaucracy, made up the middle stratum of Chinese society. It is evident that even if one should merge the upper and middle strata of premodern Chinese society, these two upper strata were but the tip of the social pyramid by comparison with the huge numbers that made up the common agricultural population.

In order to integrate China’s vast agricultural society an even more basic mode of social organization was required, one that would provide integration between the middle and upper social strata and the rest of society. This function was fulfilled by the traditional lineage system. In the history of human civilization, clans or lineages have served in the main to exclude outsiders by means of a comprehensive form of internal organization. Therefore, individual clans or lineages have not been able to merge for the purposes of forming larger organizational entities. Chinese lineages, however, not only produced internal conformity most effectively but also demonstrated a capacity for extending the reach of government into every household. The ability of Chinese lineages to complement the work of the upper and middle social strata by enabling effective governmental penetration of the lower stratum owed to the fact that they held to Confucian thought and were organized along the lines prescribed by Confucian ideology and ethics. Confucian culture emphasized the unity of lineage, society, and state, in particular the structural similitude of lineage and state, to the extent that the lineage existed as an extension of the state within the lower social stratum. In sum, the ordering of premodern Chinese society into a unified whole depended on the work of three administrative strata: the upper stratum made up of the imperial bureaucratic structure, the middle represented by local gentry government, and the lower, by the lineage household. Mutual coordination and cooperation among these three levels depended on the cultural uniformity of those in charge, namely, their common belief in Confucian ideology.Thus we can refer to this unique mode of organization in premodern Chinese society as “the integrative capacity of ideology and social organization” 意識形態和社會組織的一體化 or, in short, “an integrative structure” 一體化結構. This structure has two basic features:

- First, the countryside, not the city, forms the core of its social organization; and,

- Second, the basis of social ordering and integration takes the form of identification 認同 with a common moral ideology.

The first characteristic of this integrative structure may be described as follows:

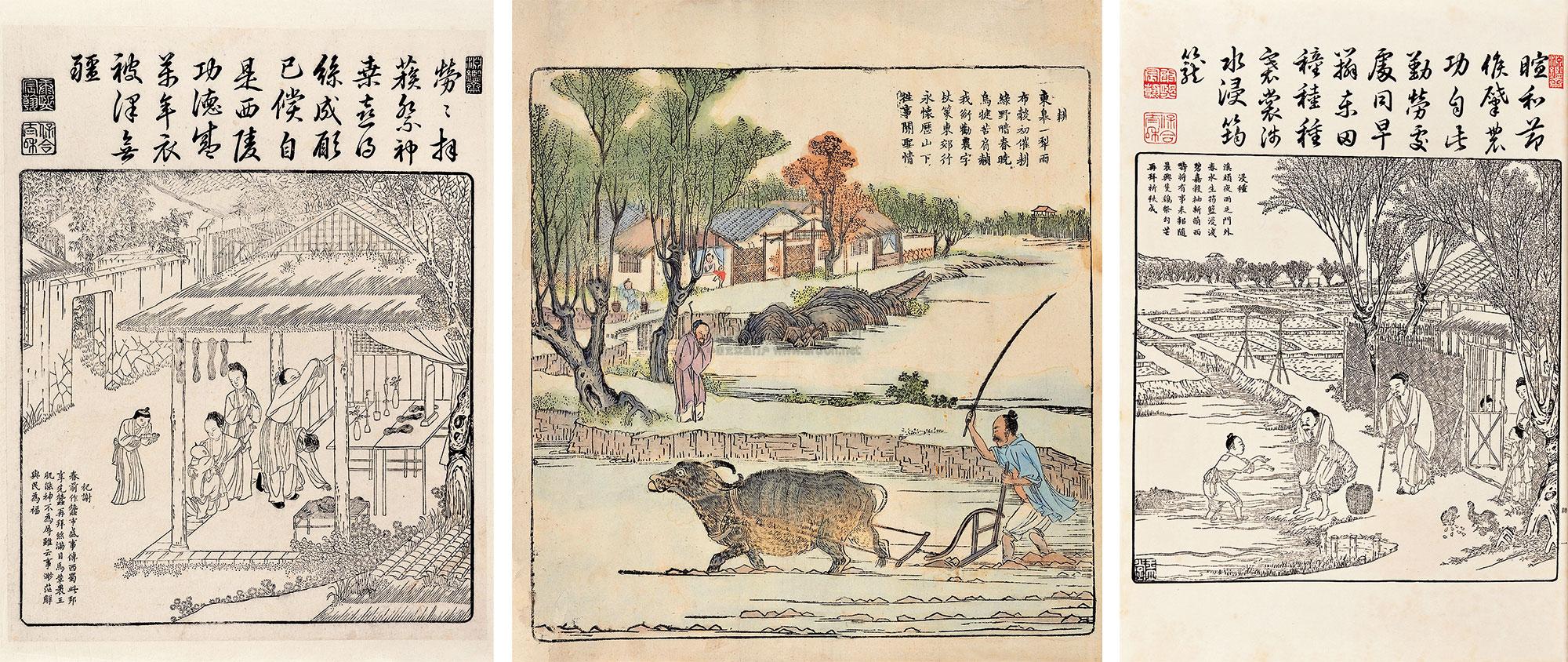

Everyone knows that the ancient Roman Empire and modern Western society were both formed around the city as their organizational core. It is not easy for a rural-based society to expand into an empire. China, however, with its unique culture, created an equally unique integrative structure and established a vast empire with a rural organizational core more than two thousand years ago. Within the integrative structure, apart from the concentration of the imperial bureaucratic upper stratum in prefectural and county cities, the other two social strata were based in the countryside. As traditional private schools 私塾 were established in rural areas, the countryside was also the base unit of the imperial examination system for determining the quota of candidates among local constituencies. The rate of literacy in premodern China was considerably higher than that of other premodern societies. Moreover, the countryside was also the core of the economy. During the Qing dynasty, revenue earned by the central authorities accounted for only approximately two percent of the gross national product, whereas the wealth controlled by the gentry accounted for some twenty-three percent of gross national revenue,[7] of which over one-third was derived from land revenue.[8]

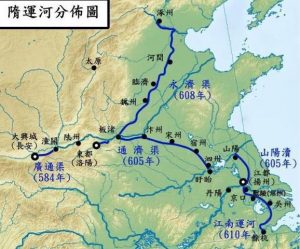

Although the countryside formed the economic and financial core of premodern Chinese society, Chinese agricultural society was integrated into a vast organic unity. Thus, despite the dispersal of wealth across many different regions, the imperial bureaucratic structure facilitated the development of China’s economic strength and amassed sufficient revenue for building the Grand Canal and the Great Wall. This also helped to create the grandeur of China’s premodern culture. These were achievements that other agricultural societies, spread out across different regions, simply could not match. The other characteristic of the integrative structure is its reliance on ideology as the basis of social ordering and integration. This helps to explain why Chinese civilization has had such a persistent life force, to the extent that it has not ruptured even once in the course of several thousand years.

In actuality, sooner or later, a superpower, however great, would have collapsed under the weight of internal corruption and social crisis. China was no exception in this regard. In Chinese history, territorial annexation and the corruption of the bureaucratic structure were major factors leading to episodic social disintegration. But because the extent of Chinese social identification with Confucian ideology was such that, as it were, “ought” could not be challenged by “is,” Confucian ideology proved immune to social crises.[9] Thus, the Confucian paradigm remained unchanged regardless of whether an already corrupt imperial regime was disintegrating or a new dynasty was being established. Accordingly, government and social order were easily restored after each great upheaval or episode of territorial annexation and corruption. This integrative mode of organization was clearly able to withstand the periodic rise and fall of dynasties. The early maturity of Chinese culture, its longevity, and the unchanging mode of its social organization over some two thousand years, not to mention the magnificence of premodern Chinese civilization, are all factors related to the unique form of Chinese social organization. Similarly, this form of social organization can provide us with insights into the changes that have taken place in modern Chinese society. It will also reveal why the process of modernization in Chinese society has been beset by many difficulties and why China’s cultural transition to modernity has been so violent.

Urbanization provided the foundation for modernization in the West and was thus a movement that saw the transformation of the countryside through the impact of cities. The mode of social organization in the West, with the city at its core, proved to be the exact opposite of the integrative structure in premodern China, where the countryside served as the organizational core. Thus, when premodern China collided with the irresistible force of Western civilization, it faced an irresolvable dilemma brought on by the contradiction between its own integrative structure and the demands of modernization. If China were to have taken stability as its guiding premise, thereby giving priority to social order and integration, its efforts to learn from the West would have shifted neither its Confucian ideological underpinnings nor its rural-centered organizational structure. As such, this would have produced only a very superficial form of modernization incapable of directing China toward developing either a modern industrial society or effective resistance to the assault of the West. Conversely, if China had given priority to modernization, then social stability would have immediately been destroyed. In other words, modernization would have led to ever increasing social problems for China in the form of regional power spills, grassroots turbulence, and disintegration of the state ideology. In reality, this structural contradiction has remained crucial to Chinese discussions on modernization from the nineteenth century to the present day.

The First Surge of Modernization:

The Self-Strengthening Movement and Qing Reform Policies

Broadly speaking, China’s rural sector in the nineteenth century was wealthier than Japan’s, but precisely because its social organizational core was in the countryside, most of the wealth was directly controlled by clan lineages. Moreover, the government was, for the most part, limited in its ability to extract revenue from the countryside. The meager tax revenue was sufficient merely for meeting the government’s own operational expenses. There was clearly nothing left over for investing in modernizing enterprises. Had tax revenue been increased, peasants would not have had the means of shouldering the additional burden because the actual tax increase would be multiplied several times as a consequence of embezzlement, a common practice among the gentry class and local government officials. The structure of the entire lower stratum of Chinese society would have collapsed under such pressure. During the Self-Strengthening Movement, both the Qing government and Chinese scholar-officials accorded the preservation of social order the utmost priority, hence the lack of adequate capital for modernization. Eighty-five percent of investments in industry and various modern undertakings were derived from customs revenue, and the rest came from regional and other forms of income. The central authorities simply had no money to invest. And as soon as the customs revenue began to be used for indemnity payments, no funds were left for engaging in modern Westernizing endeavors.[12] The state’s efforts to modernize were thus limited to the arsenal industry, but because even this part of the military enterprise was not complemented by industrial development in the nongovernment sector, it became rather like a pool of water cut off from any source. Within the integrative structure of the Chinese system, the wealth controlled by the gentry and lineages that made up the middle and lower social strata was ten times that of the government. This substantial amount of capital, however, did not flow into the cities to help initiate modernizing enterprises. Moreover, preservation of Chinese social order required continued identification with Confucian ideology at every level. It also meant that this ideology could not be changed and that the imperial examination system that it underpinned could not be abandoned. The integrative structure thus determined in advance that the only path open to China was none other than “Chinese ethical values as the foundation, Western knowledge and technology for practical application.”

Thus we can see that modernization premised on the constancy of the integrative mode of organization is not modernization at all and resulted instead in China’s inability to make modernization a reality.Conversely, if China were to have given priority to the objective of modernization, what would the outcome have been? A true modernization movement would have destroyed the existing social order; the dislocations in Chinese society after the failure of the Self-Strengthening Movement provide ample proof of this. In 1894, the Sino-Japanese War erupted, resulting in China’s defeat. In the minds of many Chinese, the outcome of the Sino-Japanese War was a test of the effectiveness of the Self-Strengthening Movement. During the movement, both the Qing court and scholar-officials had attached primary importance to maintaining social order and the integrity of the social system. They accorded only secondary importance to the modernization of the national defense system. At the time, Chinese intellectuals were by and large isolationists who viewed Western culture with total indifference. After China’s defeat, the entire country was shocked into the realization that unless modernization was given absolute priority, China would become a fallen nation. Tens of thousands of young Chinese people went to Japan to learn about Japan’s economy, law, and military affairs. The thinking of China’s intellectuals underwent a significant liberalization, and the driving force of reformist thinking that resulted from this gave rise to the 1898 Hundred Day Reform Movement. Today, when reference is made to the 1898 Hundred Day Reform of the Guangxu emperor, many believe that the conservatism of Empress Dowager Cixi led to it being aborted. They argue that, were it not for her, China might have been able to advance toward modernization at the same pace as the Meiji Reformation in Japan. In actuality, two years after the failure of the Hundred Day Reform Movement, the Qing government began reforming itself in a comprehensive way, resulting in what is now referred to as the “New Policies of the late Qing” 晚清新政. Although the Qing court did not cancel the arrest warrants it had issued for Kang Youwei and others who had been forced into exile it, nonetheless, set about adopting the specific policies that thinkers like Kang had outlined in the Hundred Day Reform Movement. Moreover, with the setting up of a new form of government administration and the moved towards constitutionalism the late-Qing court far surpassed the objectives of the original Hundred Day Reform Movement.

By 1903, the government had established a Department of Commerce that actively encouraged private enterprise and promulgated a law allowing honors and official positions to be conferred on merchants, depending on the amount of their capital investment. An investment of twenty million yuan was required for conferring the title of Viscount, First Class; an investment of 800,000 yuan was sufficient for an official title of the third grade; an investment of 300,000, for an official title of the fourth grade; and 100,000 yuan, for the fifth grade.[13]

The imperial examination system that had not been undermined during the Self-Strengthening Movement now became the target of reform. As early as 1901, the Qing government had begun to select officials from within the new-style institutions of learning. Modern degrees and scholarly honors were also equated with official positions. A doctoral degree holder was equivalent in rank to a imperial Hanlin academician because university degrees were now being equated with Hanlin ranks. College and secondary school certificates were accordingly equated with the jinshi (metropolitan) and juren (provincial) rankings under the old imperial examination system.[14] By 1905, when the imperial examination system was formally abolished, new-style institutions of learning took the place of the old private schools and nurtured great numbers of new Chinese intellectuals. The introduction of constitutionalism in 1905 had an even greater impact on China’s modernization. The years between 1905 and 1915 were a time when China’s economy developed with unprecedented speed. Before this time, machinery and industrial products in China were almost entirely imported. It was unthinkable at the time that foreign countries would place orders with Chinese factories. Yet, during these ten years, foreigners began to place orders with Chinese factories for the manufacture of industrial products for the first time, and the nongovernment industrial sector grew very quickly, to the extent that it overtook state-owned enterprises. Newly emergent cities flourished and developed with rapidity, and China’s modernization appeared to be on track. But the good times soon came to an abrupt halt. What the reformers who had given utmost priority to modernization did not anticipate was the disintegration of the order and coherence of their society as a consequence of their efforts at producing thoroughgoing reform.

The Rupture of Chinese Social Organization

Ba Jin’s novels, such as Family 家, Spring 春, and Autumn 秋 depict the process by which these great lineages fell into decline.It was after the New Qing Policies were implemented that this decline became widespread and the lower organizational stratum of Chinese society gradually disintegrated. Admittedly, lineage organization of any kind is bound to undergo some decline in the course of modernization. However, within an integrative mode of organization whereby the lineage represents the basic organizational unit in the Chinese countryside, the functioning of government within the lower stratum would be all the more adversely affected when the lineage system is undermined. What the disintegration of this basic organizational unit presaged was rural social chaos due to the absence of government. Consequently, there were both positive and negative outcomes to late-Qing modernization initiatives:

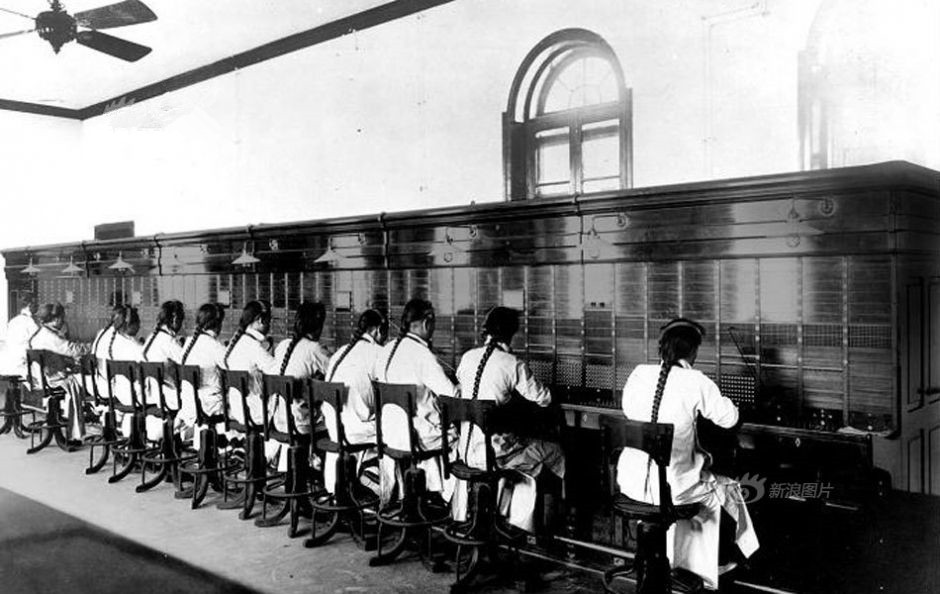

- The positive outcome was that modern cities overtook traditional cities with rapidity. Vast sums of capital and capable people with skills and talent poured into the commercial centers along the coast, making this the most developed region in modern China. For example, before 1881 the population of Shanghai was only about 500,000. By 1909 the number had increased to 1,300,000.[15] The industrial centers along China’s coastline in the twentieth century and the great metropolises all rose to prominence during this time. The annual rate of population increase in the cities was between 3.5 percent and 9.8 percent, a figure that far exceeded the annual national rate of population increase of about 0.4 percent.[16]

- The negative corollary of this development was the disruption of coherence between the upper and lower strata of the integrative structure that we have outlined. Formerly, when the gentry lived in the countryside, they were responsible for managing affairs below the county level and they constituted the essential link holding the upper and lower strata together. The urbanization of the gentry meant that the middle stratum within the structure began to shift upward, as evidenced by the decline of traditional cities, the shortage of an elite sector in the countryside, and the disintegration of the lower social stratum.

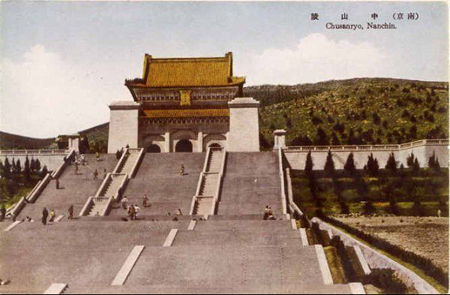

Traditional culture, likewise, was in decline. To take Xiangtan in Hunan as an example, this traditional prefectural city had a population of one million in 1870 and was even popularly known as “little Nanjing.” By 1916 its population had plummeted to 50,000.[17] The destruction of the Chinese countryside was a long-term trend, the effects of which became evident only a decade or more after it began. The rise of regionalism was the immediate outcome of this form of social dislocation.

As mentioned earlier, within the integrative structure the outermost limit of the bureaucratic machinery was county-level government, and the local gentry managed anything below that level. Originally, the middle and lower social strata were bound together through harmonious cooperation between government officials and local gentry; both groups had their own spheres of interest, and neither trespassed into the other’s sphere. As soon as the gentry entered the cities, however, their sphere of power and influence expanded to include the cities. They established Consultative Councils 諮議局 and demanded the restructuring of the political system. Thus, two centers of power emerged in the cities, with the bureaucratic institutions representing the monarchy and the consultative councils representing the interests of the urbanized gentry.

When the authority of the throne clashed with the authority of the gentry, it took the form of conflict between the center and the regions. Thus, the decade between 1905 and 1915, which saw the most rapid modernization in China through the urbanization of the gentry, was also a time that saw the sharp rise of regionalism. These developments led to the progressive distancing of local governments from the center when these proceeded to adopt an attitude of increasing independence, as was evident in events leading up to the Revolution of 1911. Whenever the Revolution of 1911 is mentioned, people immediately think of the indomitable spirit of Sun Yat-sen, who led uprising after uprising for the sake of his cause. In reality, however, the uprising at Wuchang was not directly linked to any of Sun Yat-sen’s activities. On the contrary, the year 1911 was a time when the revolutionary party 革命黨 was at its low ebb. How was it possible for the Revolution to have succeeded? In reality, it was facilitated by the expansion of regionalism.

At first, regionalism took the form of a conflict of economic interest between the center and the regions, which then triggered the events culminating in the Revolution of 1911. When the Qing New Policy initiatives were implemented, the building of railroads was accorded great importance. But because the state lacked the necessary funds, it relied solely on selling shares to the gentry to raise capital for railroad projects. This was particularly true of the Sichuan railway. At the time, any member of the gentry whose family had one or more mou 畝 of land was required to subscribe to railway shares, and thus practically every member of the Sichuan gentry ended up owning railway shares. Later, because privatization of the railway had negative outcomes, the government decided to reinstate sole control by turning the railway into a state-owned enterprise built with foreign loans. This policy directly encroached on the commercial interests of the gentry, and as soon as the news of the government’s intentions was made known, the gentry of Sichuan rose as one in opposition to it. Representatives were sent to Beijing to petition the government. Meanwhile a massive movement was launched to save the railway. In the midst of the ensuing controversy, the gentry of Sichuan decided that they would fight the government on this issue at all costs and even threatened to declare their independence from the state. The Qing government was extremely alarmed by this and sent troops from Hubei to Sichuan to crush the threat of insurrection. This greatly weakened the strength of the army in Wuhan [capital of Hubei and a strategically key city], thus enabling a small number of new-style armies to launch an uprising in Wuchang [proximate to Wuhan].

The Wuchang Uprising 武昌起義 [famed as the insurrection that led to the collapse of the Qing dynasty in 1911] was merely one episode in an already significant trend toward local claims to power. Indeed, it was only because there were already numerous declarations of independence among the various provinces that the Revolution of 1911 was successful. At the time, many of those who supported the revolutionary cause were members of the urbanized gentry, and the consultative councils representing the interests of the gentry played a significant part in the movement for independence in the provinces. Thus, the Revolution of 1911 was actually a movement toward regionalism, something that demonstrates that the old social structure had all but disintegrated. The cause of disintegration was none other than the modernization movement ushered in during the era of late-Qing reform policies. Modernization had facilitated the urbanization of the gentry, which then led the middle stratum within the integrative structure to shift upward. This caused a complete rupture of the coherence between the upper and lower social strata on the one hand and mutual conflict between the upper and (former) middle strata on the other.

Why Have Attempts at Democracy Failed?

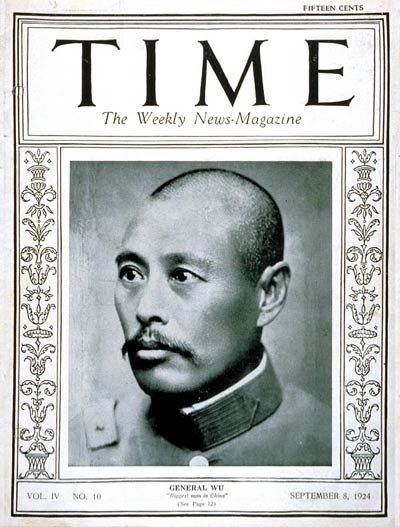

For example, in Guangdong, tax revenue in 1912 amounted to some thirty-eight million yuan, but by 1924 it had fallen sharply to 9.7 million yuan, one-quarter of what it had been twelve years earlier.[19] Soldiers once fully supported by the state now went in search of their livelihoods because the state could not afford to pay them. Between 1912 and 1922, there were more than 179 mutinies within the armed forces, the main cause being unpaid wages.[20] In order to raise funds to meet their expenses, troops merged their interests with local political forces, and this led to the development of military-cum-gentry political regimes.Another problem was the extensive degeneration of Chinese politics and Chinese culture. Statistics show that at the end of the nineteenth century, about one in every five members of the Chinese gentry (a total of some 300,000 people) had received some form of modern education.[21] They had studied either overseas or at one of the new-style institutions in China. Thus these people both upheld Chinese tradition and absorbed Western knowledge, and they constituted the life force of reform policies during the late Qing. When democracy failed in China, their leadership role in society was taken over by the warlords. The cultural standing of the warlords was considerably lower than that of the gentry. Not only were they ignorant of Western culture, they had not received an adequate traditional Chinese education either. With warlords holding the reins of government, China fell into precipitous cultural decline. For example, Zhang Zongchang, nicknamed the “Dogmeat General,” could not read even the simplest characters. As soon as he gained control of Shandong province, he merged all the universities there into a single entity, which became Jinan University, and appointed a former dux 狀元 of the imperial metropolitan examination as its president. The first thing this vice-chancellor did upon assuming office was to abolish science and to make all students memorize the Confucian classics daily [this helped fuel the radical anti-Confucianism of the following decade].Among the warlords, Wu Peifu can be considered to have been relatively well educated even though he was only a xiucai (county-level degree holder under the old imperial system). When he saw foreigners speaking their own languages, he said, “If the whole world learned Chinese, wouldn’t that make things much simpler?” Meanwhile, the constant battles the warlords waged among themselves devastated the Chinese countryside. In the decade following the Revolution of 1911, the situation in the countryside became increasingly chaotic. Because the state depended on agriculture, disruption in the countryside brought the society as a whole to the brink of acute crisis.[22]

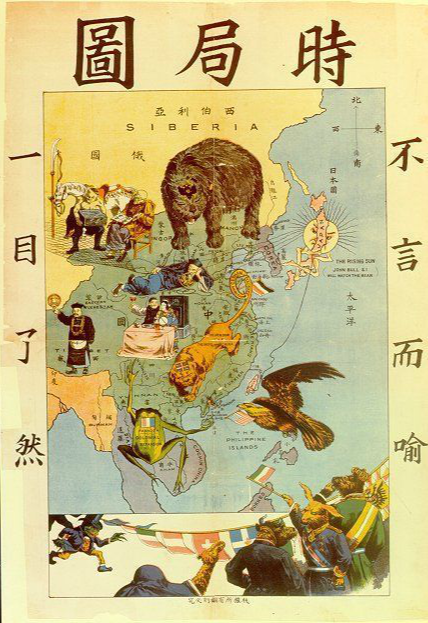

Actually, China was not a very poor nation even from the late 1890s through the 1910s. With the destruction of the countryside, however, by the 1920s, the scale of devastation was such that this former grain-exporting country now became a grain-importing country. For example, the gross output of national wheat production was 431,400,000 dan 石 (or hectoliters), but by 1923 production had fallen to 273,600,000 dan, a drop of almost 50 percent.[23] After the 1920s, the situation further deteriorated and China became “a starving nation.” After 1840, China sought mainly to find the best way to implement modernization in order to counter the impact of the West. By the 1920s, not only did this problem remain unsolved, but an even more serious and acute problem had emerged, namely, the ever worsening crisis of social order and coherence. And while the country suffered internally from increasing social chaos, externally it faced the threat of being carved up by foreign powers. China confronted difficulties unprecedented in its history. But China clearly did not disintegrate to become a colony of the West because within its ultrastable system there was a mechanism that enabled it to overcome both internal and external crises. We can think of this mechanism as “the replacement of one ideology by another.” It was put into effect by the New Culture Movement.

The Role of the New Culture Movement

- The first five-year period was dominated by antitraditionalism and was characterized by the total abandonment of Confucian thinking by the new intellectuals. The liberalization of thought that occurred during this time was historically unprecedented; this was seen as a movement toward enlightenment that would culminate in a thoroughgoing reevaluation of all values, including the creation of a modern Chinese vernacular language. Science, democracy, human rights, individualism, and so forth became the new values of Chinese intellectuals.

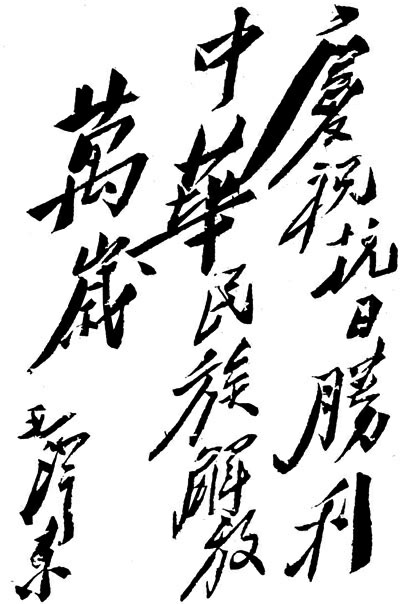

- The next five years of the New Culture Movement were dominated by new ideologies. People either put their faith in Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People or supported Marxism-Leninism and they employed these new ideological forms in their attempts to re-order and integrate society. The process of this ideological shift is none other than what is referred to earlier as the replacement of one ideology by another.

Why did intellectuals of the time choose to uphold Marxism-Leninism and the Three Principles of the People? This question cannot be answered in a few simple sentences, but it would be true nonetheless to say that the answer should be premised on the mode of organization within an ultrastable system.

For over two millennia, the Chinese had grown accustomed to the merging of moral ideology and an integrative mode of social organization. In the process of the country’s transition to modernity, a process that was not even a century old, people were not readily able to accept a new form of social organization. This is the main factor that led to the substitution of Marxism-Leninism and the Three Principles of the People for Confucian ideology. The choice of Marxism-Leninism and the Three Principles of the People was bound up with global trends in the aftermath of World War I. At the time capitalism faced a grave crisis and various forms of socialism dominated the intellectual scene. An even more fundamental factor was, as I have argued, the existence of a deep structure in Chinese culture. For instance, the matrix of ideas in Confucianism summed up by the expression “Universal Commonwealth” 大同 shares much in common with the utopian aspects of both communism and socialism, as much as the New Culture reaction against traditional Sinocentrism resonated with the notion of communist internationalism.

Thus, the replacement of the old ideology by the new during the New Culture Movement was not unlike turning a Peking Opera mask upside down. If one views an opera mask the right way up it has a particular appearance; if it is inverted, it still has the appearance of a human face, although it is a different mien. Thus, the replacement of the old ideology by the new was akin to inverting tradition by means of which some values become reversed, as is evidenced in the shift from the lineage-based family-centered moral idealism of individual cultivation to the advocacy of the moral idealism of the group and collectivism. The deep structures of both, however, are remarkably similar.

The new ideology had even greater mobilizing force than Confucian doctrine as well as a greater capacity for social organization. Marxism-Leninism is a strong ideology, while the Three Principles of the People is weak. During the New Culture Movement, the boundary between Marxism-Leninism and the Three Principles of the People was, at first, somewhat fuzzy as both were used to promote building a new China. As the old ideology was being replaced by the new, the old-style scholar-gentry were being replaced by new-style intellectuals who became the cultural elite in society. Around 1915, an essential change took place within the Chinese intellectual community. Before 1900, the Chinese intellectual elite was nurtured at traditional private schools in the villages and at old-style academies and was composed of members of the gentry and traditional scholars numbering some 1.5 million in all. After the imperial examination system was abolished, the new-style institutions in the cities became educational centers. Within the short space of ten years, the new system had trained over 4.5 million new-style students. By 1915, only some 700,000 members of the old-style gentry remained.[24]

During the New Culture Movement decade, more than ten million people — representing about ninety percent of China’s intellectuals, who were mostly young — were educated at new-style institutions. The New Culture Movement gave rise to the following historical possibility: By using a new anti-Confucian ideology as their guide, China’s new intellectuals found themselves in a situation in which they could establish an organizational system with greater mobilizing potential than had been possible under the traditional integrative structure. Because society was no longer locally managed by the gentry and lineages, it was left up to the new intellectuals to establish a colossal bureaucratic structure that could bring about social order and integration. From the start, the mission of ordering and integrating society fell on the shoulders of these new-style students, and they were a formidable generation compared with students of today. Not only were they required to be in the classroom, they had to go to the countryside as well to promote their cause and to mobilize the masses. These students believed that their responsibility extended to the whole of society and thus they became an unprecedented driving force behind the cause of modernity in Chinese society, of which the May Fourth Movement is an early and revealing example.

The China’s old society, which [as Sun Yat-sen famously observed] was like a platter of loose sand, received a sharp jolt and began regarding these well-organized students with a considerable measure of respect. Because the students took part in many different activities, such as the promotion of the workers’ movement, the organization of peasants in the countryside, and so forth, a general confusion ensued as to their proper social role and identity. Some students raised the prospect of “abolishing all examinations at school” and called for schools to be run by students themselves. Evidently, if students took on the task of organizing the upper, middle, and lower strata of society, then they would no longer be students. They would be performing the duties of military officers, politicians, and cadres instead. Within the traditional integrative structure, it was the imperial examination system that had enabled intellectuals to take on this role of social managers. However, when modern Chinese students tried to manage society, they required far more than what the imperial examination system had once provided. They required a new form of social organization that could perform the dual function that maintained a sense of shared ideological belonging through collective moral cultivation while at the same time deploying those who were ideologically unified as military personnel and politicians at all levels of society. This form of organization was established through Leninist party politics.

The Politics of Ideology and the Reconstruction of Chinese Society

The triumph of the Northern Expedition, however, also marked the breakdown of the CCP-KMT alliance and the outbreak of virulent contention between the advocates of the Three Principles of the People and the promoters of Marxism-Leninism. Although there were some ideological differences between the two parties during the first KMT-CCP alliance, they originally shared a good deal of common ground. The reason for the split was mainly the result of the dissatisfaction of landowners who felt their vested interests were imperiled by the revolution. Because many of KMT military officers were the offspring of landowners, when the Communists insisted on the overthrow of landowners and capitalists, in tandem with promoting the authority of local peasant associations after defeating the warlords, KMT cadres felt directly threatened. In order to break off from Marxism-Leninism and Communism in the aftermath of the Northern Expedition the KMT declared a purge of the CCP. It also redefined the Three Principles of the People.The KMT aimed to impose party rule over the state and to integrate its political organization with an ideology based on the Three Principles of the People. During the KMT era, party cadres played a role not dissimilar from that of the gentry and lineage leaders, reorganizing thereby the three former traditional social strata by means of a supra-bureaucratic structure. But did the KMT achieve its goal? Because the KMT had suppressed the peasant movement, it was unable to foster cadres among the peasantry to help administer the countryside. The roots of the KMT were in the city, and its members were mainly students, intellectuals, businesspeople, and workers. These urban dwellers were incapable of understanding rural life sufficiently well enough to be able administer an agricultural society. According to statistics, the task of proper reorganization and reintegration of the whole of China would have required more than ten million cadres. Before the War of Resistance against Japan (1937-1945), there were only about one million KMT members in toto. Half of these were in the military, and the remaining 500,000 were mainly based in the cities.[25] In Shanghai, for instance, there was one KMT member for every 200 people. In rural districts such as those in Shandong Province, however, there was only one KMT member for every 5,000.[26]

The KMT’s structure was like that of an inverted pyramid, with membership heavily concentrated in the urban sector and sparse in the countryside. As it was not able to penetrate effectively into the countryside, the KMT government’s mobilizing force could not properly reach the lower stratum of society. Although KMT bureaucracy, which numbered some 700,000 people, was several times larger than the former Qing imperial bureaucracy, it proved unable to extend its influence significantly beyond the latter’s reach. The Qing bureaucracy had reached its limit at the county level. The KMT further subdivided counties into districts 區 but it failed to extend its power below the district level into villages. In other words, the KMT established a government whose mobilizing capability and ability to achieve social order and integration were only slightly better than that of the former imperial government. Overall, the KMT proved itself incapable of bringing order to such a vast agricultural society, let alone being able to pursue an agenda of modernization.

Successes and Failures of the KMT

When Japan invaded China in 1937, it launched the most destructive and the largest scale assault that China had experienced in modern times. With social order having only been newly reestablished, the burden of waging the War of Resistance exacted a very heavy toll on the KMT Republican government. The only means available to a large and backward agricultural country for resisting the invasion of a small but highly industrialized nation was the relinquishing, first, of the coastal metropolises, followed by strategic retreat into the hinterland. This process allowed the Chinese government some breathing space so as to gather sufficient strength to launch a counterattack. In Mao Zedong’s words, this was a strategy of “fighting a protracted war” 打持久戰. As Chiang Kai-shek put it, it was a case of “trading space for time” 從空間換取時間.Once the War of Resistance began, the coastal cities quickly fell to the Japanese, and the KMT retreated to the Southwest. The kind of industrialization promoted by the late-Qing government and the KMT government alike during the early twentieth century was primarily limited to the southeastern coastline. The hinterland remained extremely backward. To this day southwestern China remains largely unchanged from the 1930s because many of the existing factories are a legacy of industry shifting inland from the coastal industrial districts during the War of Resistance. Some were built as a direct result of wartime requirements. But while the War of Resistance boosted the modernization of the hinterland considerably, it also meant, more broadly, the massive destruction of China’s urban economy. Once the cities fell into the hands of the enemy, the government’s tax revenue, which had largely been derived from the cities, was lost, and this undermined the very foundations of the KMT. Thus, the Nanjing-based Republican government whose viability depended on China’s urban economic base became like an uprooted tree once it was deprived of its urban power base.Forced to turn to the countryside for its sustenance, the KMT began a desperate and wanton campaign of recruiting troops and extracting tax from villages. Given that the KMT lacked an effective organizational structure and adequate numbers of cadres to administer the countryside, it turned in many instances to profiteers and local despots to collect grain levy from the peasants and to recruit able-bodied men into the army. This led to the exploitation of ordinary people on the part of ruthless opportunists who used the government’s name to serve their own selfish ends and, in turn, to the acceleration of the countryside’s disintegration.

After eight years, China finally emerged victorious from the War of Resistance, but the price it had paid for this victory was exceedingly steep. The urban economy was bankrupt, while the very basis of KMT rule had been forfeited as a consequence of overmobilization for the war effort. The printing of currency as a response to runaway inflation is sufficient in itself as an index of the damage inflicted on the urban economy. The government had no access to rural resources at the time and was thus forced to issue more currency to cope with its various expenses. A large part of the foreign debt the Chinese government owed to the United States was used for issuing more bank notes to deal with the country’s acute financial crisis. And the results of the disastrous inflation that ensued can be seen in the following figures:

- The distribution of currency in 1945 was 700 times what it was in 1937, and the price of goods was 2,000 times higher.

- In 1937, 100 Chinese dollars would have bought two cows. By 1947 this was only enough to buy a lump of coal, and by 1949, merely a piece of paper.[29]

Moreover, the people had suffered acutely under the weight of exorbitant taxes and levies.

- By 1946, the amount of grain peasants turned over to the state amounted to some 111 million tons.

- In 1947, the number of famine refugees in China reached 100 million.[30]

Thus, social order and integration collapsed under the combined effects of overmobilization and corruption from within the KMT government. It was under these circumstances that the Chinese Communist Party rose to occupy the position of political authority forfeited by the KMT.

Reasons for the Rise of the Chinese Communist Party

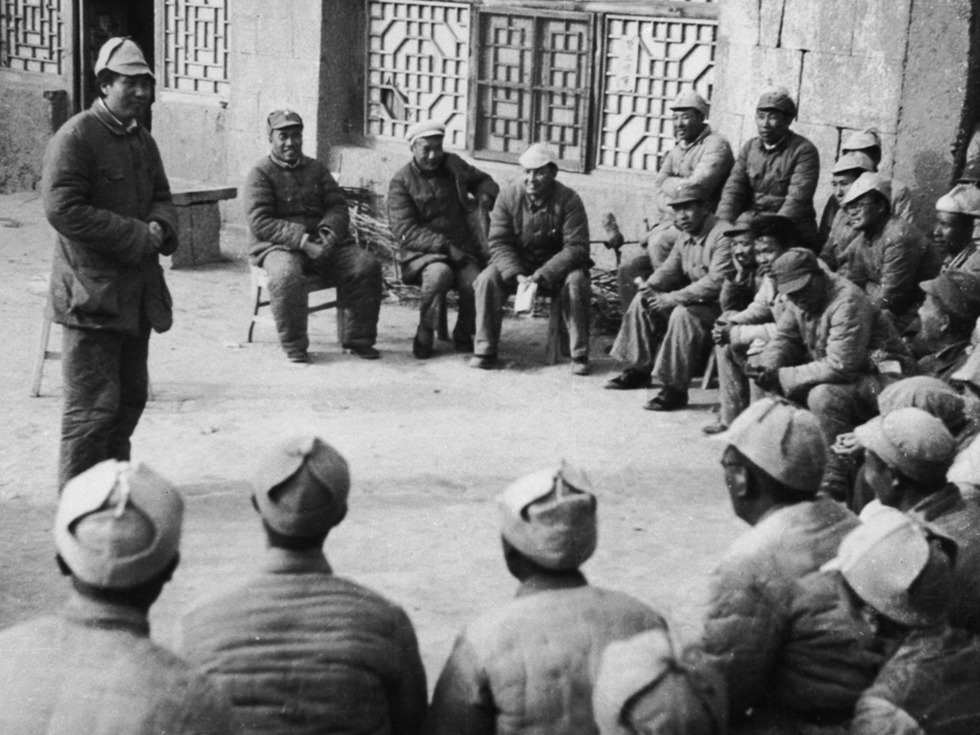

Because Marxism-Leninism originated in the West and stressed the importance of urban workers as the proletariat, some creative adaptation of Marxism-Leninism had to take place before poor Chinese peasants could be regarded as being semi-proletarian in character. Before the War of Resistance, both the right and the left wings of the CCP leadership were unable to integrate their political ideas with Chinese tradition and thus could not persuade the peasants to accept their ideas. It was not until the emergence of Mao Zedong Thought that the creative adaptation of Marxism-Leninism took place and some concordance with Chinese sociocultural conditions was achieved. It was this creative adaptation that enabled the CCP to overcome the kinds of difficulties that had bedeviled the KMT, and this process became aptly dubbed “the Sinicization of Marxism-Leninism” 馬列主義中國化. The sinicization of Marxism-Leninism entailed both rustication 農民化 and Confucianization 儒家化.Mao Zedong abandoned the Soviet theory of asserting political authority through urban revolution. Instead, he advocated the encirclement of cities by villages. Confucianization involved the merging and synthesis of Marxism-Leninism, the Confucian tradition and rural Chinese tradition. Marxism-Leninism and Chinese moral idealism originally had nothing in common, but through Mao Zedong and Liu Shaoqi’s reinterpretation of Marxist theory, both the Confucian notion of moral cultivation and the idea of proletarian sagehood became part of Chinese Marxist-Leninist thought. Chinese peasants, steeped in Confucian political culture, found it relatively easy to subscribe to such a syncretic ideology.The Yan’an Rectification campaign of 1942 saw Mao Zedong Thought assume the position of orthodoxy in the CCP and the rapid transformation of peasants into rural cadres. Membership in the CCP also increased very quickly, from 1,200,000 members in 1945, to 5,800,000 members in 1950, to twelve million members by 1957.[31] In retrospect, it would seem that the transformation of peasants into cadres was possibly the sole means of achieving social order in twentieth-century China. A most critical consequence of Chinese modernization over the last 100 years is the opposition that has emerged between the urban and rural sectors. As the elite educated youth flocked into the cities, the countryside suffered a shortage of literate and informed administrators. Integration of agricultural society and the reconstruction of the countryside could only be achieved by educating the peasants and getting them to manage their own villages. After the Yan’an Rectification campaign, the CCP effectively transformed peasants into cadres and from then on no longer suffered a shortage of cadres. Rather, it had to deal with the new problem of a surplus of cadres and the risk of a constant swelling of their numbers. As a consequence, the CCP expended considerable energies in undertaking, every now and then, “to refine and reduce the ranks” 精兵簡政 and to send surplus cadres to work within the lower social stratum while keeping active cadres on the move. The party’s rural base grew continuously from the Yan’an period onward.

A Historical Perspective

Notes:

1. [Translator’s note] In Jin’s article, the word gudai 古代, translated here as “premodern,” refers to the some two thousand years of dynastic rule that preceded the founding of the Chinese republic in 1912. Throughout this essay, Jin assumes the conventional division of Chinese history into two markedly unequal periods, gudai 古代 (about 200 BCE to the 1890s) and jinxiandai 近現代 (from the 1890s to 1949).

2. [Translator’s note] Yiti hua 一體化 is a key term in Jin Guantao’s writings, and he uses it to emphasize the interdependence and inseparability of moral ideology and social organization in his analysis of Chinese society.

3. Wang Dezhao, Qingdai keju zhidu yanjiu (A Study of the Imperial Examination System during the Qing Dynasty) (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1982), pp.62–65.

4. Jin Guantao and Liu Qingfeng, Kaifang zhong de bianqian—Zailun Zhongguo shehui chaowending jiegou (The Transformation of Chinese Society [1840–1956]: The Fate of Its Ultrastable Structure in Modern Times) (Hong Kong: Chinese University Press, 1993), p.48.

5. Jin and Liu, Kaifang zhong de bianqian, p.29.

6. Zhang Zhongli (Chang Chung-li), Zhongguo shenshi (The Chinese Gentry) (Shanghai: Shanghai shehui kexue chubanshe, 1991), pp.109–11, 166 table 32.

7. Chang Chung-li, The Income of the Chinese Gentry (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1962), p.197.

8. Franz Michael, “State and Society in Nineteenth Century China,” World Politics 7, no.3 (April 1955).

9. [Translator’s note] Jin Guantao draws attention, in this instance, to the durability of Confucian ideology and the persistence of its ethical prescriptions (the “ought to’s”), which were, he argues, never under serious threat of being undermined by (the “is-ness” or fact of) actual periodic social and political upheavals in China’s premodern history. This is also Jin’s variation of the Humean maxim that “ought” cannot be derived from “is,” by which Hume meant that evaluative or prescriptive statements cannot be derived from purely factual ones. The fact that statements can have both prescriptive and empirical or descriptive content has long since undermined the cogency of this Humean maxim.

10. John K. Fairbank, Edwin O. Reischauer, and Albert M. Craig, East Asia: The Modern Transformation (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965).

11. Gilbert Rozman, ed., The Modernization of China (New York: The Free Press, 1981), pp.75-77, 96, 98. [Translator’s note] This book was translated into Chinese and published by Jiangsu renmin chubanshe, Nanjing, in 1988.

12. Jin and Liu, Kaifang zhong de bianqian, p.84.

13. Mabel Lee, “The ‘Exalt Commerce’ Movement of Late Ch’ing,” Bulletin of the Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica 3, part 1 (1972).

14. Jin and Liu, Kaifang zhong de bianqian, p.125.

15. Liu Shiji, Ming Qing shidai Jiangnan shizhen yanjiu (A Study of Townships in Southern Jiangsu) (Beijing: Zhongguo shehuikexue chubanshe, 1987), p.100.

16. Zhou Xirui, Gailiang yu geming—Xinhai Geming zai lianghu (Reform and Revolution—The 1911 Revolution in Hunan and Hubei) (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, 1980), p.144.

17. Chang Peng-yuan, “Jindai Hunan de renkou yu dushi fazhan” (“Population and City Growth in Hunan Province down to 1930”), Taiwan shifan daxue lishixue bao (Bulletin of Historical Research), no.5 (1977).

18. Jin and Liu, Kaifang zhong de bianqian, p.169.

19. Li Guoqi, “Song Ziwen dui Guangdong caizheng de gexin (1924–1926),” in Jindai Zhongguo quyi shi yantao hui lunwen ji, vol. 2 (Taipei: Zhongyang yanjiu yuan, 1986), p.498.

20. “Minguo yilai 179 ci zhi bingbian” (“179 Mutinies since the Founding of the Republic”), Dongfang zazhi (Eastern Miscellany) 20, no.1 (January 1923).

21. He Yuefu, “Wanqing shishen yu jindai Zhongguo de shehui bianqian—Jian yu Riben mumo meizhi shizu bijiao” (“Gentry during the Late Qing and Social Changes in Modern China”) (Ph.D. dissertation, Zhongshan University, Guangzhou, 1992), pp.67–68.

22. Su Yunfeng, “Minchu zhi nongcun shehui” (“Rural Society during the Early Years of the Republic),” in Zhonghua minguo chuqi lishi yantaohui (1912–1927) lunwen ji (Proceedings of the Conference on the Early History of the Republic of China 1912–1927) (Taipei: Institute of Modern History, Academia Sinica, 1984), p.646.

23. Wang Quanguan and others, Zhongguo xiandai nongmin yundong shi (A History of Modern Chinese Peasant Movements) (Henan: Zhongyuan nongmin chuban she, 1989), pp.15, 25.

24. Su Yunfeng, “Minchu zhi zhishifenzi (1912–1928),” in Diyijie lishi yu Zhongguo shehui bianqian yantao hui (The First Symposium on History and Chinese Social Change), part 2 (Taipei: Institute of the Three Principles of the People, Academia Sinica, 1982).

25. Yang Youjiong, Zhongguo zhengdang shi (A History of Political Parties in China) (Taipei: Shangwu yinshu guan, 1969), p.200.

26. Yang, Zhongguo zhengdang shi, p.396.

27. Shi Quansheng, ed., Zhonghua minguo jingji shi (An Economic History of Republican China) (Nanjing: Jiangsu renmin chubanshe, 1989), p.236.

28. Parks M. Coble Jr., Jiangzhe caifa yu guomin zhengfu (The Tycoons of Jiangsu and Zhejiang) (Tianjin: Nankai daxue chubanshe, 1987), v. See also Zhang Yufa, Zhongguo xiandai shi (Modern Chinese History) (Taipei: Zonghua shuju), p.498. [Translator’s note] The original English version of Coble’s book, The Shanghai Capitalists and the Shanghai Government 1917-1927, was published by Harvard University Press in 1980.

29. Hu Dekun, Zhong-Ri zhanzheng shi (1931-1945) (A History of the Sino-Japanese War [1931-1945]) (Wuhan: Wuhan daxue chubanshe, 1988), p.401. See also Sun Wenxue and others, Zhongguo jindai caizheng shi (A Financial History of Modern China) (Dongbei caijing daxue chubanshe, 1990), p.341.

30. Lin Dequan, “Jiefang zhanzheng shiqi guotongqu jingji weiji de tedian ji qi genyuan” (“Characteristics and Causes of Economic Crisis in KMT-held Areas during the War of Liberation”), Xiangtan daxue xuebao, no 2 (1985).

31. Zhao Shenghui, Zhongguo gongchandang zuzhi shi gangyao (An Outline of the History of CCP Organization) (Hefei: Anhui renmin chubanshe, 1987), pp.208, 282.