Intersecting with Eternity

天籟之音

June Fourth 2024 marks the thirty-fifth anniversary of the Beijing Massacre. It was an event that had a monumental impact on the fate of China, as well as on the future of the world.

That event also had an impact on the life-trajectory of Amor Towles, a best-selling novelist who we previously encountered in Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People (13 July 2020).

***

Intersecting with Eternity is an occasional series in The Tower of Reading that features essays, poems, art works, music, video and miscellanea that speak beyond their time. Our assemblage is an idiosyncratic selection that allows the reader/ viewer to leave, even for a moment, the ‘dusty world’ of contemporary concerns to skirt the ineffable. The eternity to which these works grant access is not there and then, but here and now.

Immortality appears in three guises: that of virtue, of worldly contribution and of expression. They are immortal because time does not weary them.

太上有立德, 其次有立功,其次有立言,雖久不廢,此之謂不朽。

— 左傳·襄公二十四年

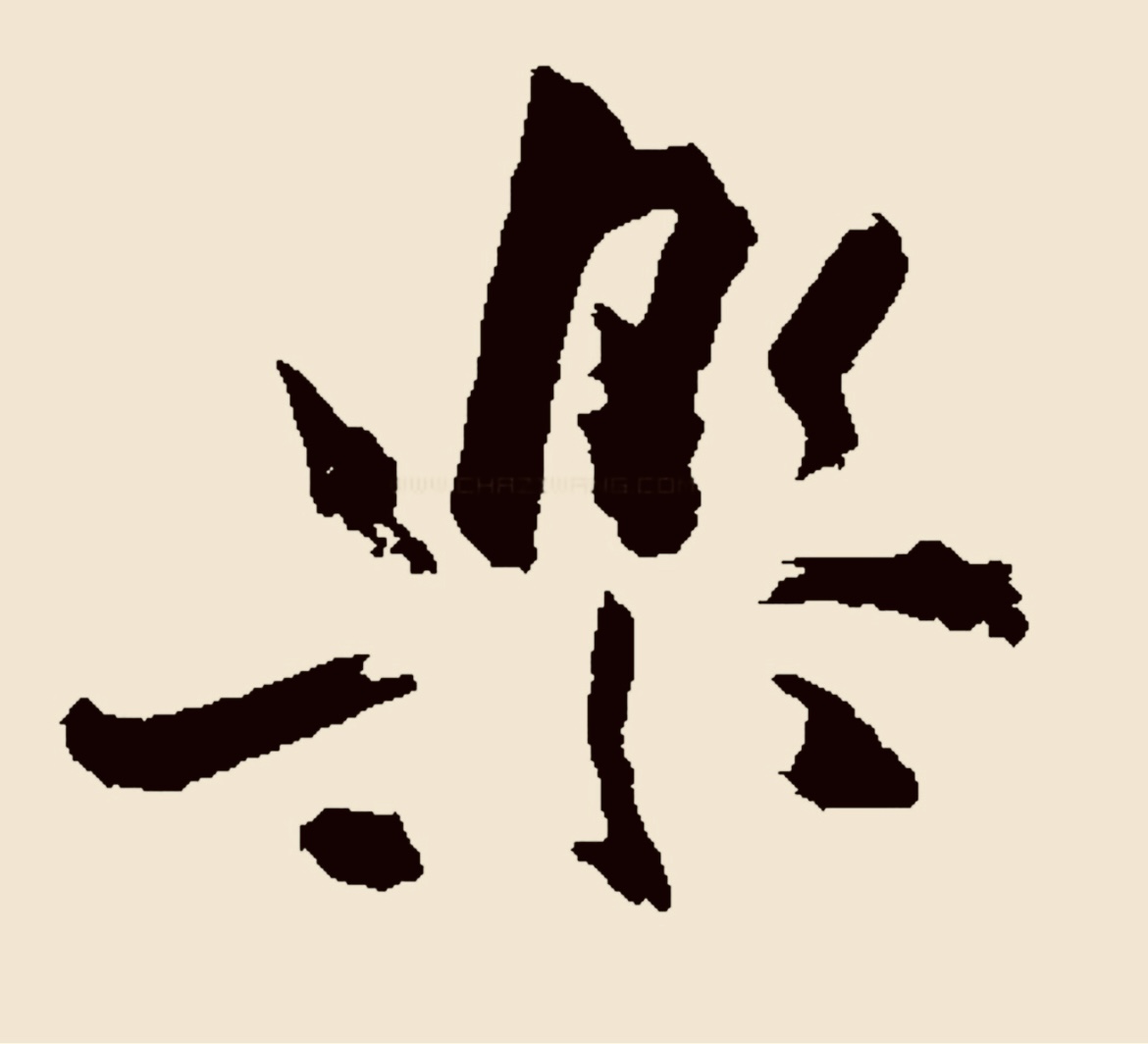

The Chinese rubric of this chapter is 天籟之音 tiān lài zhī yīn, ‘the piping of Heaven’, first occurs in Zhuangzi, ‘All Things Made Equal’ 莊子·齊物論.

For another chapter in Intersecting with Eternity, see In Cloudy Mountains, an Impossible Realm 絕境非凡境, 30 April 2024.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 May 2024

Q. Talk about the role of chance encounters in the book.

A. One of the central themes in the book is how chance meetings and offhand decisions in one’s twenties can define one’s life for decades to come. I think there is something universal about this dynamic; but it was certainly my experience.

In 1989, I had a fellowship to teach for Yale in China for two years. I came back from California to New Haven to spend the summer learning Chinese, but because of Tiananmen Square, Yale cancelled the program. They gave us each a few thousand dollars and sent us on our way. I had all my belongings in my car and had no idea what to do with myself. As it turned out, an old friend needed a roommate in New York to split the rent, so I moved here.

My first night in the city, I got invited to a party at the home of an acquaintance. There, I met a few people who ultimately became close friends. In retrospect, a number of careers and marriages sprang from the intersection of social circles at that party – but we certainly didn’t realize the importance of the encounters at the time. We were just meeting for drinks, making haphazard alliances and cursory decisions, shaping our futures unwittingly.

— from Amor Towles, Rules of Civility: Q & A

- See also, Book Tour: At home with Amor Towles, Washington Post, 18 May 2024

***

The arts are not a luxury. They’re how we know we’re not alone.

– W.O. Mitchell

***

***

An Ascension

Amor Towles

Here’s the ironic part:

That third Saturday in April, when Tommy opted to excuse me, excuse me, excuse me right in the middle of the performance, I was aghast.

In fact, I was so aghast, the only way I could think to stave off my embarrassment and retain the goodwill of those around me was to give 100 percent of my attention to the performance, for a change. No snowy night by a lamppost; no Gene Kelly or Jimmy Stewart; no girls in pigtails chewing Fruit Stripe gum. Just the cello, the cellist, and me.

As Tommy exited the hall, Mr. Isserlis finished the piece he was playing. Then after drawing a watch from his pocket, he joked that his accompanist must have been feeling unusually upbeat, because they had finished the first half of the program two and a half minutes early. Once the audiences laughter had died down, Mr. Isserlis said that to ensure we didn’t feel shortchanged, he would now play something not on the program – the prelude to the first of Bach’s Suites for Cello (in G Major).

Before beginning, the cellist gave a brief history of the suites, noting that for hundreds of years they were all but forgotten until they were rediscovered in the late nineteenth century by a thirteen-year-old prodigy named Pablo Casals. Apparently, Casals had happened into an old music shop near the harbor in Barcelona and found the suites buried under a stack of musical scores, crumpled and discolored with age. Years later, as a world-famous cellist, Casals championed the suites at every opportunity, bringing them the attention they so rightly deserved.

Or, so concluded Isserlis.

Once again, there were whispered remarks in the audience, then a collective silence set off by a few coughs. Once again, the cellist laid his bow across his cello, closed his eyes, and began to play.

How to describe it?

I never studied music or played an instrument. I rarely sang along in church. So, I don’t know the proper terminology. But once Isserlis was playing, within a matter of seconds, you could tell you were in the presence of some form of perfection. For not only was the music uplifting, each individual phrase seemed to follow so naturally, so inevitably upon the last that a slumbering spirit deep within you, suddenly awakened, was saying: Of course, of course, of course …

And as the music washed over the audience, Isserlis somehow conveyed the improbability of it all through his playing. For surely, it was all so improbable. To begin with you have the fact that some crumpled old sheet of music, which could have been torn or tossed or set on fire a thousand times over, had survived long enough to be discovered by a boy in an old music shop—in a harbor in Barcelona, no less. The very cello Isserlis was playing had survived two and a half centuries despite the fact that its entire essence seemed to depend upon the fragility of its construction. But the greatest improbability, the near impossibility, was that somewhere in Germany back in seventeen something something Bach had taken his deep and personal appreciation of beauty and translated it so effectively into music that here in New York, hundreds of years later and thousands of miles away, thanks to the uncanny skill of this cellist, that appreciation of beauty could be felt by every one of us.

About a minute and a half into the piece, after a series of low and almost somber notes, there was a slight pause, a near cessation, as if Bach having made an initial point was taking a breath before attempting to tell us what he had really come to say. Then from that low point, the music began to climb.

But the word climb isn’t quite right. For it wasn’t a matter of reaching one hand over the other and pulling oneself up with the occasional anxious glance at the ground. Rather than climbing, it was … it was … it was the opposite of cascading a fluid and effortless tumbling upward.

An ascension.

Yes, the music was ascending and we were ascending with it. First slowly, almost patiently, but then with greater speed and urgency, imagining now for one instant, and now for another, that we have reached the plateau, only for the music to take us higher still, beyond the realm in which climbing can occur, beyond the realm in which one looks down at the ground, beyond hope and aspiration into the realm of joy where all that is possible lies open before us.

And then, it was over.

Oh, how we applauded. First in our chairs, and then on our feet. For we were not simply applauding this virtuoso, or the composition, or Bach. We were applauding one another. Applauding the joy which vc had shared and which had become the fuller through the sharing.

As we applauded, everyone in every aisle was looking to the left and right such that suddenly I and the old man were nodding at each other with smiles on our faces in acknowledgment of what we had just witnessed, what we had been a part of.

***

Source:

- ‘The Bootlegger’ in Amor Towles, Table for Two, Penguin, 2024, pp.176-179

***