Spectres & Souls

‘Over One Hundred Years’ is a series of essays published by China Heritage to mark the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party. The series is included in China Heritage Annual 2021, the theme of which is ‘Vignettes, moments and meditations on China and America, 1861-2021’.

Below we reproduce an oral history interview from The Rings of Beijing, Inside Beijing’s Global Aura, an account of the People’s Republic of China compiled by Sang Ye and Geremie R. Barmé. The following translation of the interview conducted by Sang Ye 桑曄 in 2009 originally appeared in the September 2011 issue of China Heritage Quarterly, the predecessor of China Heritage, the theme of which was 1911 Xinhai Revolution and its aftermath.

This account can fruitfully be read as a companion piece to ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, published by SupChina on 24 August 2021.

I would like to acknowledge Linda Jaivin for her many helpful suggestions and I am grateful to Lois Conner for permission to reproduce her work here.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

4 September 2021

- Note: The standardization of place names in the People’s Republic means that the place known to earlier generations as the town of Bose 百色 is now Baise City (Baksaek Si in Zhuang). Here we retain the older reading. In 1929, a Communist-instigated rebellion against the local Nationalist forces at Baise was overseen at a distance by Deng Xiaoping. The Bose Uprising 百色起義 is also known as the Youjiang Riot 右江暴動.

***

Related Material:

‘Over One Hundred Years’

(essays on the centenary of the

Chinese Communist Party

in China Heritage Annual 2021)

- Liang Hongda 梁宏達, et al, ‘5.16 — Sorry, Not Sorry’, China Heritage, 16 May 2021

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, et al, ‘In Memoriam — 4 June 2021’, China Heritage, 4 June 2021

- G. Barmé, ‘Beijing Days, Beijing Nights, May 1989’, China Heritage, 4 June 2021

- Isaiah Berlin, et al, ‘Xi Jinping’s China & Stalin’s Artificial Dialectic’, China Heritage, 10 June 2021

- Lee Yee 李怡, ‘Apple Daily, “The Four Noes” & the End of Chinese Media Independence’, China Heritage, 24 June 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, A.M. Rosenthal, et al, ‘Beijing, 1st July 2021 — ‘It was a sunny day and the trees were green…’, China Heritage, 1 July 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold’, China Heritage, 13 July 2021

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, SupChina, 24 August 2021

Accounting for 111 Years

The Wang Family of Bose, Guangxi Province

An oral history interview by Sang Ye 桑晔

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Wang Dan, female, thirty-eight-years old, Nanning, Guangxi, university lecturer.

My grandfather was born into a landowning family in 1898. He had one older sister. When he was only two a plague killed both his father and his grandfather. The village was devastated: men carrying coffins one day would be carried out themselves the next. It was a cholera epidemic, originally confined to the Ganges River delta. When the British opened India up to global commerce they also broke the cordon sanitaire that had prevented the spread of cholera. India was no longer isolated and the contagion arrived here in Guangxi.

When my granddad was thirteen, the 1911 Xinhai Revolution erupted. He was studying in a private school and his queue was cut off. That’s what my uncle and father told me. They also said that when he was nineteen, he married the daughter of another landowning family; she’d lost both of her parents in the great cholera outbreak of 1900.

My paternal grandmother was raised by her uncle. He had a son, my own uncle, who joined the revolutionary troops under the command of Sun Yat-sen against the Northern Imperial Army. That led to him becoming a soldier in Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist Army. He fought in the Civil War, he fought the Japanese, and then he fought in another Civil War. My grandparents on my father’s side had four sons and four daughters. First Uncle Zhong was a good student; he became a teacher. Second Uncle Xiao wasn’t a good student so he ended up in the army. He joined the Guizhou Army of Li Zongren, a Nationalist Army that wasn’t under central command. Third Uncle Xin was regarded as solid and reliable so he stayed at home to work in the family business. After the founding of New China [in 1949], he was an accountant in a rural cooperative before getting fired. The fourth son, He, my dad, was born in 1946.

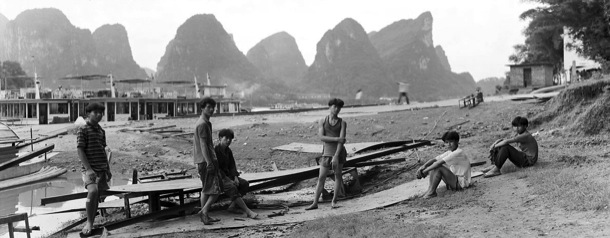

Yangshuo, Guangxi. (Photograph: Lois Conner)

As for the four girls, the first two obediently married the sons of family friends. Of the other two, one married for love and the other was sold for a bag of black beans. To be more specific, my Eldest Aunt was married at the age of thirteen to a boy from a family that wasn’t particularly well off but had close personal ties with my granddad. Second Aunt’s marriage was also arranged, but she married into a landowning family. She ended up suffering [the political consequences of owning land] along with them. Though third Aunt chose her own mate, the Anti-Rightist Campaign started soon after she was married and her husband was classified a Rightist. She divorced him and remarried, this time to a gambler. During the Great Leap Forward and the famine Fourth Aunt was married off deep into the mountains after my granddad agreed to a bride price of fifty catties of black beans.

When he was young, Granddad often stayed with his maternal grandmother. So he ended up being very close to his younger cousins. The older of them followed the Nationalists, the younger the Communists. They despise each other to this day; not even their kids will have anything to do with each other.

My mother’s situation was pretty straightforward. She was also born into a landowning family, but her dad passed away before the Land Reforms, so he was never dragged into a struggle meeting. His widow was classified as a landlord’s wife, however, and their kids were classified ‘sons of bitches’ [狗崽子].

When the People’s Republic of China was founded [on 1 October 1949], Bose was still in the hands of the Nationalists, though everyone knew they wouldn’t be able to hold out for long. The ‘Others’—the Red Army, the Communists—were on their way, fighting southwards. They say that the Others only had to let off a few cannonades and the Nationalists in Bose collapsed.

Second Uncle, the one in the Nationalist Army, was always writing home with reports of fierce fighting. Suddenly, there was no news from him. Later we learnt he’d been ‘liberated’ in Hunan province, that is, taken prisoner. They didn’t even change his uniform; they just ripped the Nationalist insignia of the White Sun against the Blue Sky off his cap and he became a People’s Liberation Army [PLA] soldier. He turned around and fought his way back south with the Others, right down to Hainan Island, fighting against his former comrades-in-arms.

Some of the villagers who’d joined the Guizhou Army were captured and became PLA; some fled into the mountains and became bandits. Others just ran straight back home. The saying has it that ‘when an army falls it’s like a mountain collapsing’. I suppose that pretty much wraps it up. My uncle reappeared around that time. He’d been an officer in the Nationalist Army; he’d backed the wrong side. He snuck back home believing he could just ‘lay down the butcher’s cleaver and instantly become a Buddha’.

Before the final takeover, my granddad was terrified by talk that the Others were going to make everything public property. He did something completely ridiculous. In reality, he didn’t own that much property by then anyway. More than half of his forty head of farm cattle had died of bovine typhus after the victory over the Japanese. There weren’t even enough left to plough the fields. Add to that high government land taxes and he’d already had to sell off a lot of his property. The family was in rapid decline. But granddad was so fearful of the Others that he lost all sense of proportion. Unbelievably, he herded his remaining dozen or so cattle into Bose township for my eldest aunt to hide along with my dad, who was very young. My aunt’s husband was a government employee. He had no idea how to look after cattle and, in any case, he had nowhere to graze them. The only thing he could do was to sell them quickly and cheaply.

After the Other’s Land Reform Team entered the village, they determined everyone’s class status and divided up land and property accordingly. All the terrible things that had bankrupted my granddad—the plague of bovine typhus, the heavy taxes, the selling off of his land, and the cheap sale of his remaining herd in Bose—are, in the end, what saved him. He was classified as a Rich Middle Peasant, a farmer whose exploitation of others was minimal, and who ‘belonged within the ranks of the People’, even if on the lowest rung. He was not a target of Land Reform; he retained his rights as a citizen.

First Uncle Zhong was a teacher in town so he wasn’t assigned a class status back home, nor was he allocated any agricultural land. But a few years later he was attacked as a Rightist. Second Uncle Xiao was a ‘liberated’ member of the People’s Liberation Army, so he was classed as a Revolutionary Soldier. Later he was de-mobbed and sent home and, for some bizarre reason, classified as a Poor Peasant. Third Uncle Xin had stayed at home like my dad and he was also classified as a Rich Middle Peasant. My dad was too young to be assigned class status in his own right.

Things were worst for my maternal uncle. He was classified as a Landlord and a Counter-Revolutionary Official in the Nationalist Army. His whole family was executed. Only later did Beijing issue an order instructing local authorities to take more care and execute fewer people, as well as banning the execution of the children of reactionaries. By then it was too late: about a dozen members of the family, including grandchildren, had all been murdered. No one even dared give the bodies a decent burial. They were wiping out the enemy root and branch—if you went to retrieve the bodies you’d be eradicated as well. My paternal grandmother’s parents had died long before, so my maternal uncle was my grandmother’s only close relative. Devastated by grief, she took to her bed and within a few days she too was dead.

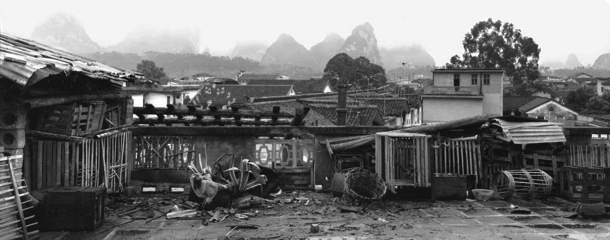

Village, Guangxi. (Photograph: Lois Conner)

Soon after that the Movement to Eliminate Counter-Revolutionaries was launched. This time around only one of my relatives was killed. My mother’s brother-in-law was teacher in a primary school. He didn’t have much experience of the world. When he saw the Others grabbing people right there in the street he was so terrified he started running in the direction of his school. The Others were carrying guns and they shot him dead on the spot. Later they had to come up with an explanation and said he’d been killed by mistake. But, they said, both parties shared responsibility. Of course, it was wrong to open fire on him, but he was wrong to have taken fright and run at the sight of counter-revolutionaries being arrested. If he hadn’t run he wouldn’t have been shot. Nothing more could be done about it now. So the mainstay of that family was suddenly taken away and they fell into ruin. My aunty was left a widow with a baby only a few months old.

He might have been the only one of our relatives killed that time, but there were many others who were purged and forced to return to our village because of their class status or counter-revolutionary history. There was my grandfather and his cousin who’d been in the Nationalist Army along with First and Second uncles. Some had been in Nanning, Liuzhou or even in the city of Bose, holding government positions or doing business—regardless of their occupation they were all fired and forced back to the village to work the fields. Even the uncle who had been ‘liberated’ and served in the People’s Liberation Army was purged, although they rewarded him with the good class status of Poor Peasant.

Something else happened during the Land Reform Movement. My mother’s aunt had married into Yuchang before the Anti-Japanese War. Her house was opposite that of the most prosperous landlord in the district. Her husband caused some sort of scandal with the landlord’s concubine, after which he died from an unspecified illness. After the Others arrived, they told her daughter that her daddy had been secretly murdered by the landlord and it was time for her to exact revenge. They had her tell her tale of woe at a public struggle session against the landlord and after she’d said her piece they handed her a gun and told her to shoot him. That girl is my aunty. At the time she was only a girl of fourteen.

From there on in we had the Anti-Rightist Movement [of 1957], the Four Cleans Campaign [of 1964] and the Cultural Revolution [1966-76]. It was like incessant channel surfing on a TV, and it left us feeling dazed and dizzy. My uncle ran into trouble during the Anti-Rightist Movement. He was teaching in Nanning and said something the Others didn’t like so they struggled him and sent him off to labor reform. He managed to survive up to the Cultural Revolution, but then they declared that besides being a Rightist, he was also a Landlord who had slipped through the net. The commune sent a group to drag him back home so that the Poor and Lower Middle Peasant Revolutionary Tribunal could put him on trial and execute him.

All the way home, they didn’t let him eat or drink. When they reached the commune, the place previously called Yuchang, they gave in to his pitiful pleading and let him kneel down to drink some stagnant water from a roadside ditch. My mother happened by and saw him there. The leader of the Cultural Revolution in the commune at the time was none other than the husband of that aunty who had shot the landlord during the Land Reform Movement. He dressed in an old army uniform and leather boots, a pistol tucked into his belt. Later he became the head of the Revolutionary Committee and lorded it over everyone for a whole ten years.

The only reason my uncle survived was that my mother begged this revolutionary and his wife to show some mercy. Of course, he still had to be struggled and beaten. They’d made such an effort to drag him all the way from [the provincial capital] Nanning, after all. If they didn’t lock him up for a few months and give him a number of proper beatings, the revolutionary masses would have felt cheated; they would have lost face. That couldn’t be tolerated. Originally, they’d really been planning to kill him. The Poor and Lower Middle Peasant Revolutionary Tribunal consisted of the great unwashed: they’d scream out some slogans and call it a trial. By then they’d already dispatched all of the Landlords, Rich Peasants, Reactionaries, Bad Elements and Rightists. They’d sent a group to Nanning to nab my uncle because they couldn’t find any other locals to execute.

The husband of my Third Aunt was also a teacher who got into trouble during the Anti-Rightist Movement. After they’d been forced to divorce, she married a gambler, but because this lout had a good class background from then on my aunt was at least safe politically.

There was famine during the Great Leap Forward [of 1959-61]. That’s when my grandfather had my youngest aunty, Fourth Aunt, married off into the mountains. You could say that she was sold into the mountains for fifty catties of black beans. Even those beans couldn’t stave off starvation. After my cousin—the son of Third Uncle—died of starvation my dad knew he’d never survive if he stayed in the village. So he ran off to join the district dam-building brigade as a child laborer for Chairman Mao. Creating jobs on dams and for other infrastructure projects was a way to provide some relief for people. He was only a skinny-ass kid of thirteen but they gave him a food ration, which he saved up to help keep my grandfather alive.

Things in my mother’s village were even worse. Corpses were a common sight; lots of people died. My mom says the only people who survived did so by foraging in the hills outside the village for wild fruit and tree leaves. After the leaves were all gone they went deeper into the mountains. She went with them. One time, she says, she was so hungry she thought she was about to die when suddenly she found a sweet potato. It saved her. She was going through puberty during the famine, and thanks to years of undernourishment she didn’t get her first period until she was twenty. By that time, her mother, my grandmother, had forced her into two marriages. Each time, her husband’s family sent her back home because she wasn’t menstruating and couldn’t have children. My grandmother regarded boys as superior to girls; she ill-treated my mother, using her like a beast of burden so that her boys, my two maternal uncles, could get an education and secure their future. Gran often dragged my mum out of school. She beat her and cussed her and made her work in the fields to support the family.

(Photograph: Lois Conner)

The only one in our family who remained unharmed throughout all the campaigns of the new society was my granddad’s younger first cousin. He was a Communist Party member and completely loyal to the cause. He actively denounced ‘remnants of the Nationalist era’ to the Party organization: that is to say, he sold out his older brother, leading to the destruction of his whole family. These two granduncles of mine had taken different ideological paths during the split between the Communists and the Nationalists, and their different choices turned into personal enmity. Their descendants inherited this mutual hostility; neither side will have anything to do with the other. When the obituary was sent out following granddad’s death the cousins finally got in touch with my family again. My elder granduncle is an old man who’s no longer particularly engaged with the world and fairly cool towards others. His younger brother, who has retired from his job as Party secretary in a state-owned enterprise is warm and chatty and his family is very well off.

Following the Cultural Revolution, First Uncle, who had been denounced as a Rightist, was rehabilitated and sent back to teach school. But his political status meant his sons were deprived of educational opportunities. Like the children of all the other ‘Black Five Categories’ [黑五類:地富反壞右; Landlords, Rich Peasants, Reactionaries, Bad Elements and Rightists] their options for education and work were severely limited. No matter how clever they might be, they never had the opportunity to study, so they had no choice but to work in the fields. Even the children of Rich Peasants were widely discriminated against when it came to education, employment and promotion. The offspring of Landlords, Rich Peasants, Reactionaries, Bad Elements and Rightists faced worse—in some cases struggled against and killed for no other reason than that they were born into the wrong family. To this day these people have received not even one word of apology, let alone any financial compensation.

With the rise of Deng Xiaoping came another turn of the wheel. My revolutionary aunt and uncle were fired from their jobs because they were now classified as belonging to the ‘Three Categories of People’ who had built their career on rebellion [三種人:打砸搶分子; those who had been involved in leading or inciting Cultural Revolution-era mob violence, destructive activities and plunder]. Depressed and a broken man, my uncle died of cancer a few years later. My aunt was left with the children, but she had no land to till and no work. She is, however, articulate and argumentative. She lodged numerous appeals claiming that she wasn’t a bad person, that from the days of the Land Reform she’d been unfailingly loyal to the Party. Maybe the authorities got sick of the constant haranguing, or maybe they really had some sympathy: in any case, she and her children were given back their urban residency permits, as well as some money in reparation. They used it to start a small business.

That aunt has a fetish for collecting new clothes. She has chests full of brand new outfits. In her free time she lays them out on the bed so she can look at them. But she never wears them; she only ever wears old clothes.

Granddad passed away in 1981. Six months before his death he had a picture taken of himself standing beside the outdoor stove at home. He looks anxious. The picture still hangs in First Uncle’s house.

About a month after granddad died, a man who looked just like him came to our house. He said he used to work for the family; he had grown up with granddad and that they’d been like brothers. He’d been sent off at the approach of the Others. He never thought that he wouldn’t be able to see our grandfather before he passed away. When I first laid eyes on the man I thought granddad had been resurrected. They looked so much alike that it was a shock. My uncles said that the family had employed several workers in the past but they’d never seen this one before. We took him to granddad’s grave and he cried. Then he just went away without leaving an address. He hasn’t been back. Who he really was remains a mystery, one that granddad took to the grave.

It was also not long after granddad’s death that we had visitors from the Zhuang ethnic areas deep in the mountains. That’s how we learned that when my maternal grandfather’s family had been exterminated, their youngest son had managed to escape. He’d kept his identity hidden for decades. Only now did he dare come back home to see us. He’s my maternal uncle. His wife is an ethnic Zhuang. She’s illiterate and can’t speak Mandarin, nor can their children.

Not long after granddad died, his sons started bickering over the pitiful inheritance he’d left. Extreme material deprivation naturally makes people fall into a bestial state; they become deceitful and blinded by greed until any shred of decency has been shed. One day, when my dad was away at work, my aunts removed all of my granddad’s things from his little room. They then invited my elder sister to join them in dividing up the spoils. She came back with three sewing needles and an earthenware pot. My aunts also divvied up the land that was in my granddad’s name and my uncles cut down his fruit trees. My father thought it unfair and went to argue with them but their sons beat him up. Humiliated, my father took it out on my mother. You see, dad had grown up without a mother himself so, after granddad died, he thought of his brothers as his only family. He believed that underneath it all they were good people but that they’d fallen under the influence of their evil wives. The only thing wrong with his brothers was that they’d taken the side of their wives. From that point on dad lost all faith in his own wife and he became convinced that at any moment she too might turn and become like my aunts.

When my father and Second Uncle came to blows it only entrenched his prejudices against women. When we were doing renovations to our houses the plan was that our house would be connected to that of Third Uncle, while First and Second uncle would have their houses joined in a row. But First Uncle’s wife disagreed. They had more sons and her husband had always wanted to have a study, so she wanted extra land. So our house ended up being built inbetween that of First and Second uncle.

Longshan, Guangxi. (Photograph: Lois Conner)

Later, Second Uncle’s daughter-in-law had a miscarriage, for which he blamed my father. He claimed that our house was blocking the fengshui of his daughter-in-law’s bedroom, preventing it from opening out to the alleyway, therefore my dad had used fengshui to murder his unborn grandson. Second Uncle told him, ‘I deeply regret having sent money home when I was a soldier to keep you alive, because now you’ve repaid me by killing my grandson.’ ‘That’s crap’, replied my father. ‘When you came home from the wars you sent me out to herd cows all day long, it was worse than working as child laborer for Chairman Mao.’

Then they set to each other. For the most part Second Uncle beat my father with a wooden club. Fleeing back home amidst a rain of blows, my father turned on my mother: ‘Everything that goes wrong is caused by the meddling of you women!’ And that led to another massive row. They too came to blows. My family entered a long period of internecine warfare, both hot and cold. My father became increasingly irascible and, regardless of what my mother said or did, he’d scream that it was all a plot because she was a woman and women are evil.

During the long years of ‘war’ my eldest sister fell from a tree and damaged her eye. Even now she has to wear glasses with a prescription of over a dioptre. Second Sister left home when she was fourteen and ended up being kidnapped and sold. It was three years before she managed to escape back home.

When I went to university in Nanning my parents came after me and haggled over my fees in front of my classmates. They fought over who had put up more money. I was so mortified I wished I were dead. Their constant bickering has torn our family apart. They were determined to torment one another, to fight to the bitter end. But they refuse to get a divorce. When the arguing reaches its most vicious, all that one of them had to do is scream out ‘Divorce!’ and the other backs down immediately. The fighting would subside only to be replaced by a cold-war standoff until there was another outbreak of conflict a few days later.

Lots of girls were abducted from Bose. Most were sold off to people in eastern Guizhou and western Guangdong. Both Third Aunt and my mother’s sister had children stolen. Third Aunt’s daughter was sold in Guangdong. They say she died. My mother’s sister lost her daughter to traffickers who sold her in Qinzhou. She was then resold, and only released and allowed to come home after she’d give birth to two children.

Since the advent of the new millennium some family members have died off. The others are still living the same same way they did before; they’re just older.

Eldest Uncle Zhong is still alive. He’s nearly ninety now. Although his hearing isn’t very good, he’s in fine health. He tells me that he gets a monthly pension of 3000 yuan from the school where he taught, but since his ‘worthless sons’ all depend on him he can’t die. Returning to his hometown after retirement, his dream was to get enough money together to build himself a study. In the twenty years since, he’s never been able to save up enough.

Second Uncle Bo died of stomach cancer. He was having problems with his stomach even before he took to my father with that club. Dad had taken him to Nanning for an operation. But after their falling out, Uncle Bo even demanded back an old cotton jacket he’d given him as a present. They cut off all relations. While putting his things in order after his death, Second Uncle’s wife found his old military uniforms in a trunk—both the Nationalist and PLA uniforms. Second Uncle was a wily man.

Yangshuo, Guangxi. (Photograph: Lois Conner)

Third Uncle Xin had been an accountant in a rural cooperative, but was given the sack when some money went missing. He was a man without ambition, but his wife always put on airs. After he was fired, he had to put up with her constant scolding. It went on for three decades, right up to when he died of liver cancer. My mother thinks that he embezzled the money. His job didn’t pay much but his wife was quite a big spender back in the day.

My own father is getting on now. He’s particularly nostalgic for the happy days of his youth. None of his childhood companions made it through as well as he did. During the Great Famine he fled to work on the dam project and stayed in hydrology right up until he retired. So he has a pension, unlike all the pals of his youth who spent their lives farming the land. He’s ended up as the leader of the pack, a position bought with money and material gifts: he pays for their drinks and often gives away the clothes and food that we’ve given him. With all the alcohol in his system, his violent temper and controlling nature have only got worse. He lavishes praise on me as a way to manipulate his old childhood friends—that’s because I’m the only one of my generation in the Wang family who’s made anything of themselves.

My father’s great comrade-in-arms, my mother, avoids him at all costs. She’s a student of Chairman Mao’s dictum on guerrilla warfare [敵進我退,敵退我追,敵駐我擾,敵疲我打; ‘When the enemy attacks our forces retreat; we pursue when the enemy retreats; when the enemy rests we harass; when the enemy is exhausted our forces attack’]. When dad’s at home in the village she comes into the city to stay with me or my elder brother. When he comes to the city she heads off back home. My dad is always looking for a fight, but can’t find an adversary, so he expends his energy on bribing and controlling his old buddies. He’s tried training ‘dog slaves’ to do his bidding without bribes. The first was poisoned—he had this weird idea, as ridiculous as that time my grandfather drove his cows into town, and fed the dog washing powder to treat its worms. It died as a result. When the second dog disobeyed him, he kicked it to death right in front of all of his buddies.

So that’s the story—1898 to 2009, one hundred and eleven years of family history. You want ‘oral history’—this is oral history.