Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

Voices of Protest & Resistance (XXX)

In both the May Fourth Era (1917-1927) and during the post-Mao decade (1978-1989), Chinese intellectuals hailed the country’s intellectual and cultural rebirths as an ‘Enlightenment’. The European Enlightenment is also known as The Age of Reason and 30 September 2019 marks to the day two hundred and thirty five years since the German philosopher Immanuel Kant published ‘An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?’. The term he used for Enlightenment was Aufklärung, to shed light, elucidate or to educate. Although the common Chinese translation of this term is 啟蒙 qǐ méng, one that emphasises the sense of ‘education’, it can also be rendered as 啟明 qǐ míng, ‘to make luminous’ or ‘open the way to insight’. It is also an ancient name for Venus, the Morning Star.

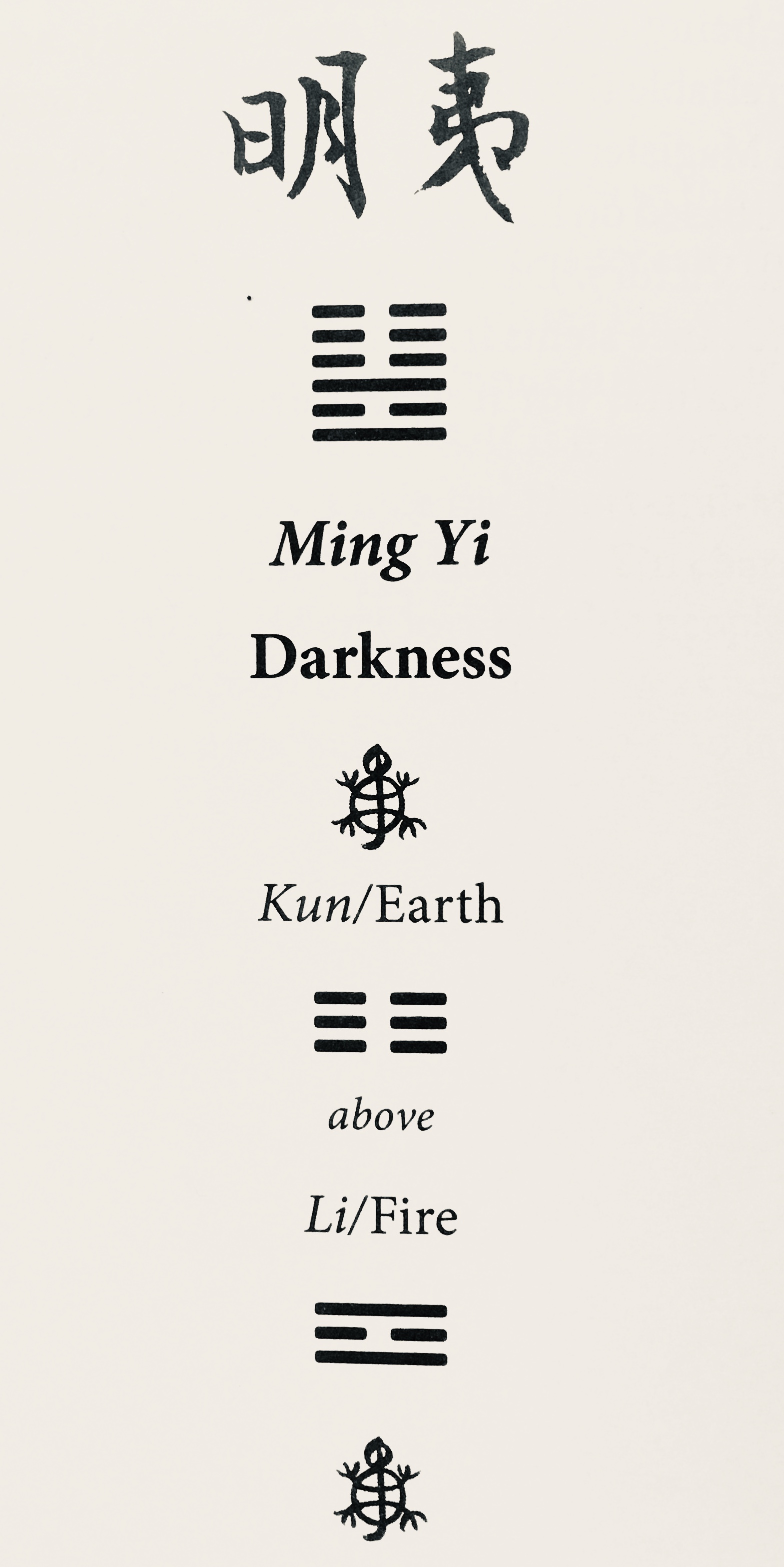

It is also three hundred and fifty years since Huang Zongxi (黃宗羲, 1610-1695) published his famous treatise on political reform titled 明夷待訪錄, or Waiting for the Dawn (明夷 míng yí, ‘Darkness’, is Hexagram Thirty-six in the I Ching — see below). This important tract condemns autocracy and is one of the first works in the Chinese tradition that advocated ideas related to constitutional law. Published in the early Qing era, it became widely discussed as dynastic rule faltered in the late-nineteenth century. Huang has been dubbed ‘Father of the Chinese Enlightenment’ 中國思想啟蒙之父. He famously declared that government ‘should be for the weal of all, not solely for the ruler; it should benefit all people, and not be the preserve of one Surname [family lineage] 為天下, 非為君也; 為萬民, 非為一姓也. Huang’s words have resonate in an era in which once more autocracy would claim that China is the preserve of only ‘one surname’, that of The Party 姓黨.

Today, on the eve of the seventieth anniversary of the founding of China’s People’s Republic, we mark the anniversary of Kant’s essay by publishing a short reflection by one of the country’s most outspoken advocates of enlightenment. During 2019, many supporters of the Tsinghua University professor Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 have spoken out in his defense. They have done so despite the lengthening shadows of China’s new Dark Age. We would note, however, others have preferred a studious silence over even the most modest gesture of valour. Their number includes some of the most famous on-paper advocates of Liberalism and the benighted history of the Chinese Enlightenment.

***

This stark memoir ends with a note about how Xu Zhangrun’s family once fortuitously avoided disaster. In describing that good fortune, Professor Xu uses the expression 躲過初一 duǒguò chūyī, which I translate here as ‘calamity passed us by’. It is the first part of a two-part expression that goes: 躲過初一, 躲不過十五 duǒguò chūyī, duǒbùguò shíwǔ, that is, ‘you might avoid the debt collectors when they come calling on the first of the month, but they’ll be back on the fifteenth and you won’t be able to escape them then’. In other words, you might avoid trouble when it knocks the first time, but sooner or later it’ll catch up with you.

As Professor Xu noted during our recent correspondence, it would appear that a long-delayed debt to the country’s political radicalism had finally come due, seemingly with compound interest. From the moment that Tsinghua University launched its formal persecution of him in March 2019, Xu Zhangrun has been in the clutches of the debt collectors.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

30 September 2019

Feast Day of Jerome the Hermit

Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus

Patron Saint of Translators

***

- Karl Leonhard Reinhold, ‘Thoughts on Enlightenment’, translated by Kevin Paul Geiman in James Schmidt, ed., What Is Enlightenment? — Eighteenth-Century Answers and Twentieth-Century Questions, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996

- Xu Jilin, ‘The Fate of an Enlightenment: Twenty Years in the Chinese Intellectual Sphere (1978-1998)’, trans. G.R. Barmé and Gloria Davies, East Asian History, no.20 (2000): 169-186

- Ya-pei Kuo, ed., A Century Later: New Readings of May Fourth, Twentieth-century China, vol.44, no.2 (May 2019)

- Maura Cunningham, ‘May Fourth at 100: A Reading Round-Up’, 6 May 2019

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤 Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

***

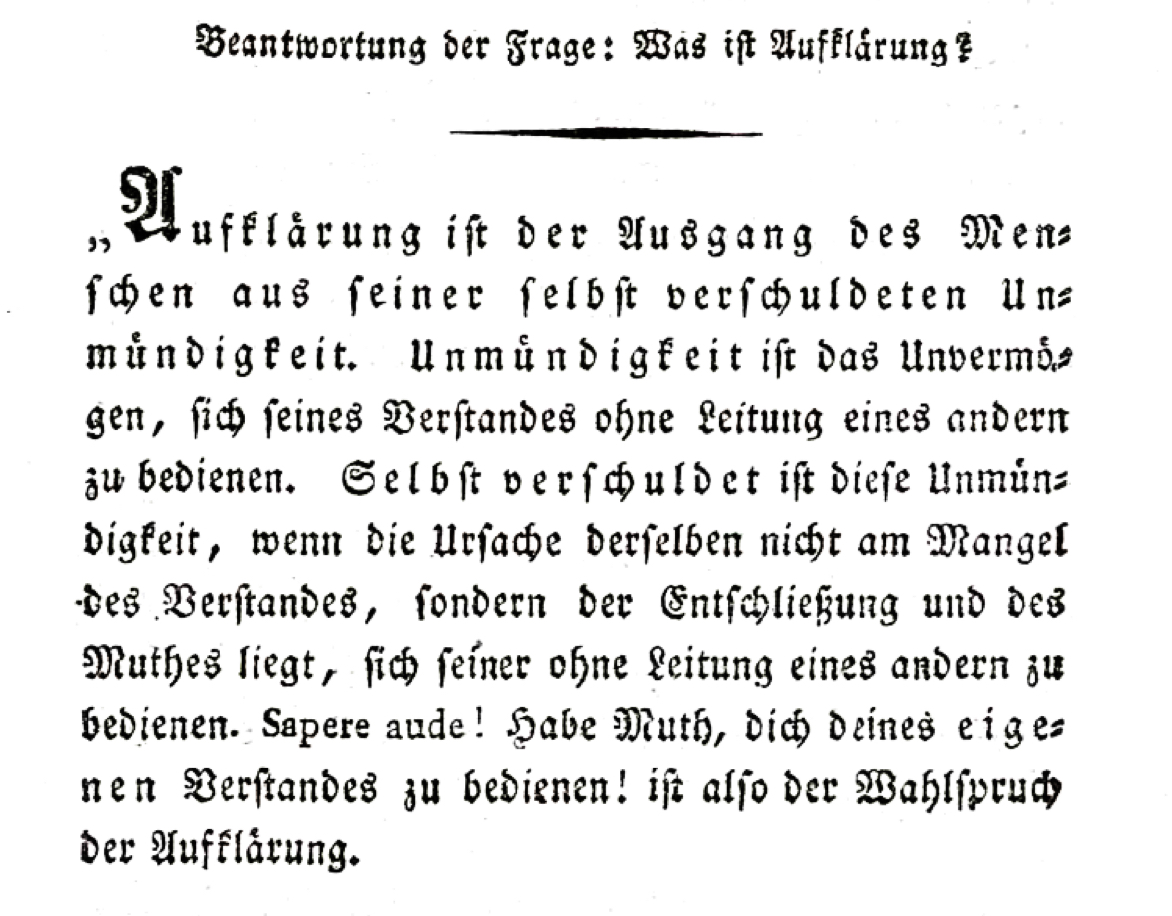

Aufklärung

Elucidation

啟明

Enlightenment is man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is the inability to use one’s own understanding without the guidance of another. This immaturity is self-incurred if its cause is not lack of understanding, but lack of resolution and courage to use it without the guidance of another. The motto of enlightenment is therefore: Sapere aude! Have courage to use your own understanding!

… …

A revolution may well put an end to autocratic despotism and to rapacious or power-seeking oppression, but it will never produce a true reform in ways of thinking. Instead, new prejudices, like the ones they replaced, will serve as a leash to control the great unthinking mass.

For enlightenment of this kind, all that is needed is freedom. And the freedom in question is the most innocuous form of all — freedom to make public use of one’s reason in all matters.

— from Immanuel Kant, ‘An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?’, Konigsberg, Prussia, 30 September 1784

***

Waiting For The Dawn

坐待天明

Xu Zhangrun

許章潤

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

My father left home when he was thirteen to pursue his studies in the city. He was particularly attracted to a normal college there that neither charged any fees nor made students pay for their accommodation. On top of that, meals were subsidised up to the equivalent of three pecks of rice [approximately 12.5 kilograms] per month.

Like my father, most of the other students were from poor families; they were all studying with a hope that, after a few years, they would be able to go home with a diploma in hand so they could make a living both for themselves and their families by teaching. That’s how it came about that my father was able to persevere with his studies in the city in a relatively unhurried fashion.

It came as quite a surprise then when, after only one year there, the school authorities suddenly announced that all students would be required to join the Three Life League under the aegis of the Nationalist Party [that was the ruling party of the Republic of China]. Anyone who refused to join up would either have to leave the school or, if they wished to continue there, they would be required to pay tuition. This new regulation was being imposed in a manner that hijacked young people by forcing them to support the further encroachment of one-party rule at the time.

I believe that this rule was applied in schools throughout China at the time so most octogenarians alive today will probably remember it. Anyway, League membership required no formal procedure; everyone was simply signed up en masse.

And so that’s how my fourteen year-old father became a fully fledged member of the Three Principles Youth League. No one really appreciated what membership actually meant, but it was a fateful moment, for it not only determined his future fortunes, it also cast a long shadow over his family, and in particular over the lives of his children for the first three decades of Communist rule following the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949.

家父十三歲離家進城讀師範,圖的是減免學費、提供伙食外,還給每月三斗米的零花錢。讀師範的一般多為寒門子弟,希望兩三年畢業,回鄉做個教書匠,謀個養家糊口的生計。如是這般,風前雪底,清霜暖日,暫寄個輕閒時光。不料,一學年之後,校方突然宣佈所有學生必須加入三民主義青年團,否則,要麼退學,要麼自己負擔一切費用。此為新例,旨在裹挾國民,強化黨國一體,據說全國通行,如今八十歲上下的老輩過來人,可能都有印象。

無需任何手續,全校學生集體加入。

於是乎,這個十四歲少年成了一名三青團員,餘生的命運和家小的命運,在城頭換幟之後的三十年里,便都拴在這大家都不明所以的什麼團上了。

I recall one particularly bitter month in the middle of one winter — the year and date are not important. There was a piercing light reflected by the frozen water of the river that day, more dazzling because of the bright morning sun making everything particularly clear. A meeting had been called at Shengqiao Bridge — my hometown — one which Zhang Guangsheng, the Machine Shop Communist Party Branch Secretary had called. The Party Committee was mobilising as part of the larger political movement [that is, the Cultural Revolution]. Later we heard it was a ‘strategy planning meeting’ to discuss particular ‘revolutionary actions’ being launched so as to take movement to a higher level of radicalisation.

One of the key ‘actions’ they initiated was a targeted ransacking of the homes [of people identified as counter-revolutionaries who might have previously disclosed dark histories, hidden artefacts or who were engaged in underhand schemes and plots against the Party]. Young people today can, at best, get some idea of the kind of frenzy people back then worked themselves into if they watch those historical recreations on TV. But, frankly, you should thank your lucky stars that you were born too late to have had the dubious honour of witnessing in person such things with your own eyes.

Anyway, at that particular mobilisation meeting Party Secretary Zhang made a point of insisting that the homes of all former members of the Three Principles League [back in the Nationalist era] had to be included in the hit list.

某年某月某日,寒冬臘月,記得清晨河上冰凌泛光,朝霞映照之下,愈發清純。盛橋鎮,吾鄉,機械廠支書張光聖,急匆匆參加區委會召開的動員大會。據說,會上「研究部署」了幾項「掀起運動新高潮」的革命行動,抄家是重頭戲。如今的青年或許能從電視上的歷史劇中領略此項風景,但餘生也晚,卻與有榮焉,多次目睹親歷真人秀,真要感謝時代。「老三青團員」的家,在張支書的堅決要求下,榜上有名。

There is a well-worn line from the German Enlightenment [in an essay by Karl Leonhard Reinhold] that holds that:

‘The spiritual darkness of a people must often become so thick that the people bumps its head, if it gets the idea to look for the light.’

And, back in the year, China certainly had its fair share of those who were willing to crack their skulls in their dark ignorance. Though in our insignificant little town there no one was stupid enough to want to dash their head against a brick wall on purpose. Heaven-born decency can be found everywhere, and there were those who had a conscience. A senior member of our clan just happened to be at that crucial meeting. Since he couldn’t stand the thought of what was about to unfold he surreptitiously alerted our mother to the bad news. He urged her to prepare for an onslaught.

德國啓蒙時代的一句名言是,「一個民族精神上的黑暗經常必會變得如此沈重,以致它不得不撞破腦袋來尋求光明」。當年中國撞破腦袋的,不乏其人。小鎮無人犯傻撞頭,但天良自在人心,不比人少。與會的一位同族長輩,於心不忍,偷偷告訴家母這一噩耗,告誡趕緊做些準備。

We had the most basic kind of existence — a small place with the bare essentials — containers, vessels and the like, the common chattels of everyday life. It was pretty much a bare slate and so there was no need to prepare in particular for a home invasion. Nonetheless, after a lot of thought my mother decided that the only really precious things we owned were our household registration documents and our ration book [in which the monthly allocation of staple grain was recorded]. She hid them in her clothes and would guard them closely. Our father happened to be out of town and there was no way we could let him know what was about to befall us. That night we had dinner early and mother told us — my three brothers and sisters and me — to keep close by and sit there quietly as darkness fell. She didn’t even bother locking the front door.

家裡只有罈罈罐罐,四壁如洗,無須準備。想來想去,只有戶口本和糧本最為重要,母親將它們揣在懷裡。家父離家在外,不可能知情,也無法聯繫。一家早早吃了晚飯,母親帶著我們兄妹四人,靜候夜幕降臨,乾脆連門也不關。

Around midnight, we heard the tramping of feet on the street outside. Soon there was a thumping on doors, angry shouts and plaintive screams followed by a great din — people rummaging through cupboards and rifling through storage bags along with the racket made by things being moved around roughly. After that, all we could make out was the muffled sounds of walls being hacked into and ripping up of floors [in the search for proof of long-hidden plots against the party and the state].

The simple structures along our little street were built right next to a waterway and the floors were wooden planks that were cantilevered over the river on stakes. We were, quite literally, riparian dwellers. So, when the invaders set to ‘digging things up’ what they did was pull up the plank floors of the houses; as they did so we heard the scant belongings of our neighbours plonking loudly into the water below. Front doors were closed tight and there was no light anywhere; even the village dogs had been terrified into silence. But the furious sounds of plunder pierced the pitch night, just as the lamplight of the wreckers flashed around erratically casting shadows against walls like quivering phantoms.

夜半時分,街上腳步嘈雜。先是打門、呵斥和哭喊,繼為翻箱倒櫃、搬東運西的碰碰撞撞,最後只剩下鏟牆挖地的悶聲。這條小街,臨河而建,都是吊腳樓,河上架樁,樁上鋪設木板,便成河岸人家。於是,挖地連帶著撬木搬板,間或聽見家什掉落河水,咣咚,咣咚。家家大門緊閉,黑燈瞎火,好像連狗也不再叫喚。漆黑的夜幕下,只有被抄的人家,燈火忽閃,人影幢幢。

Three people killed themselves that night.

The Ou Family had been classified as Landlords [during the fixing of class status in the early 1950s]. Now, the elderly grandfather of the family simply cast himself into the river and drowned. He’d already had a near-death experience over a decade earlier at the time they repressed counter-revolutionaries [which led to millions of deaths]. They hadn’t killed him back then and, although he wasn’t directly threatened that night, he simply decided he couldn’t take it any more. I suppose he no longer had the will to live.

Another was a distant relative of ours, a member of a family that was under investigation for some ‘crime’ or other. They simply broke free of the invaders and threw themselves into a nearby well. It was freezing, so the thugs decided to make sure they were dead before pulling the corpse out of the well the following day.

The third person died just as the darkness was about to lift. No one would have ever guessed that this man — a respected old teacher who previously had instructed many local people — would simply dash his head against a wall and die.

It turned out that the invaders hadn’t found anything in his home despite spending ages rifling through all of his possessions. Then, just as they were about to withdraw, one of their number — a stern enforcer of the proletarian dictatorship — noticed a small mirror hanging on the back of the front door. He grabbed it to claim as his spoils but, upon inspection, he found there was a faded image on the back. He called the rest of the gang together to study it and one of the older people in the group was able to make it that the faded picture was of none other than ‘Baldy Chiang’ — the Enemy of the People of China, Chiang Kai-shek [head of the Nationalist Party that had lost the civil war with the Communists in 1949].

That discovery reignited the passions of the invaders and they knocked the old teacher down. He was then made to kneel before them and confess. But the mirror was a meagre token of his marriage and he had only kept it safe these past forty years because it represented the deep affection he had for his wife. He had long ago forgotten about that dastardly image on the back. There was nothing more he could confess but they laid into him regardless and beat him demanding answers. He must have felt that there was nothing for it, so the old man broke free and dashed his head against a brick wall and expired.

那一夜,三人自盡。歐家,地主成分,祖父當即跳河。早在十多年前「鎮反」之際,老人家就已「陪斬」過一回,如今無此榮耀,卻反而想不開了,怕是實在沒了留戀生的慾望了。遠房親戚,查家,也是老祖,衝出家門,跳井。寒冬臘月,等待他的自然只有死亡,直到第二天家人才敢去撈上屍首。最後,拂曉時分,誰也沒想到,一位受人尊敬的私塾老先生,居然撞牆而死。原來,查抄一宿,毫無所獲,正準備鳴金收兵之際,專政人員看到門口一個小圓鏡子,順手牽牛,打算據為己有。反轉端詳,鏡後居然有一人像,影影綽綽,眾人仔細辨認,其中一位年長者發現,不是別人,竟然是人民公敵蔣光頭。頓時,士氣大振,立馬將老先生打翻,罰跪在地,責令老實交代。這小圓鏡子是老先生結婚時的信物,留存四十年,只為記著老伴的情義,早已忘掉鏡後的鬼頭。講不出所以然,再打,老人奮力衝向石牆。

That night, before launching their ‘revolutionary action’ they had gone over the hit list one last time. For some inexplicable reason one of the people in charge simply decided to cross off the name of the Xu Family — our family — from the list of suspects. It was simply by chance then that, this time around at least, we managed to avoid disaster. Many years later, only when the sulphuric stench had finally dissipated, one of the people involved in that deadly night told my father that’s how calamity passed us by.

Through those dark night hours the five of us — our mother and my siblings — sat clutched closely together fully dressed and with our bedding wrapped tight around us. And we all sat there together silently, waiting for the dawn.

When no one came and as the new day approached our mother got up and bolted the front door. We all fell asleep at once.

半夜行動之前,他們再次覈實名單,一位負責人員,不知為何,主張將許家划掉。於是,躲過了初一。多年以後,煙消雲散,當年的當事人如是告之。

那一夜,我們母子五人,和衣擁被,坐待天明。天亮了,無人上門,於是母親將門關嚴,安頓孩子們睡去。

6 September 2009

Erewhon Studio

Tsinghua University

2009年9月6日

於清華無齋

***

Source:

- 許章潤, ‘坐待天明’, 三會書坊 No.1091. This essay was included in a collection of essays published by the Guangxi Normal University Publishing House in 2013 titled Waiting for the Dawn. See 許章潤著, 《坐待天明》, 廣西師範大學出版社, 2013年

Freedom from Self-incurred Immaturity

The guardians who have kindly taken upon themselves the work of supervision will soon see to it that by far the largest part of mankind (including the entire fair sex) should consider the step forward to maturity not only as difficult but also as highly dangerous. Having first infatuated their domesticated animals, and carefully prevented the docile creatures from daring to take a single step without the leading-strings to which they are tied, they next show them the danger which threatens them if they try to walk unaided. Now this danger is not in fact so very great, for they would certainly learn to walk eventually after a few falls. But an example of this kind is intimidating, and usually frightens them off from further attempts.

Thus it is difficult for each separate individual to work his way out of the immaturity which has become almost second nature to him. He has even grown fond of it and is really incapable for the time being of using his own understanding, because he was never allowed to make the attempt. Dogmas and formulas, those mechanical instruments for rational use (or rather misuse) of his natural endowments, are the ball and chain of his permanent immaturity. And if anyone did throw them off, he would still be uncertain about jumping over even the narrowest of trenches, for he would be unaccustomed to free movement of this kind. Thus only a few, by cultivating their own minds, have succeeded in freeing themselves from immaturity and in continuing boldly on their way.

— from Immanuel Kant

‘An Answer to the Question:

What is Enlightenment?’

***

I Ching

Hexagram XXXVI

地火明夷

Judgement

In hard times,

To be steadfast

Profits

利艱貞

On the Image

Light enters Earth,

The True Gentleman

Governs the Folk.

The Light is veiled,

But it still shines.

明入地中

君子

以蒞眾

用晦而明

— trans. John Minford