狂人之末日

Li Ao 李敖, a famously controversial writer and media personality based in Taiwan, died on 18 March 2018. For many former admirers Li’s end really came in 2004. His passing gives us pause to consider the plangent fate of this ‘madman’.

The following essay and translation were first published by China Channel, Los Angeles Review of Books on 30 March 2018. I would like to thank the editors of China Channel for their support, their editorial suggestions and for permission to reprint this material. Minor emendations have been made to that earlier version of the text.

I’d like to think that Liu Xiaobo would appreciate the fact that ‘A Madman’s End’ is appearing in China Heritage on April Fool’s Day.

— The Editor, China Heritage

1 April 2018

***

It is impossible to describe the exhilaration I felt reading Li Ao’s A Monologue on Tradition 獨白下的傳統 when it first appeared in 1979. At the time, I was working for The Seventies Monthly 七十年代月刊, a prominent Chinese-language magazine edited by the noted Hong Kong journalist Lee Yee 李怡. After years studying in late-Maoist China where I had been immersed in the works of the Great Helmsman #1 and reams of stilted Party prose, the initial shock of Hong Kong’s cultural and linguistic richness was immense. The British Crown Colony was the entrepôt of the Chinese multiverse, one where traditions from before 1949 and the world of that ‘Other China’ Taiwan were freely accessible; they jostled with an atavistic form of capitalism as well as with a flourishing publishing industry under a colonial rule that was ever mindful of the cloaked realm of the People’s Republic of China.

And then there was Li Ao 李敖: his prose, and his ideas, were liberating, scintillating and, after my time on the Mainland, bracingly scandalous. I was soon surreptitiously ferrying copies of A Monologue on Tradition — a collection of essays on history and the Chinese national character — to friends in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Around that time I launched my own writing career as a Chinese essayist (one which lasted from the late 1970s until the early 1990s); Li Ao 李敖, among others writers, was both a challenge and an inspiration.

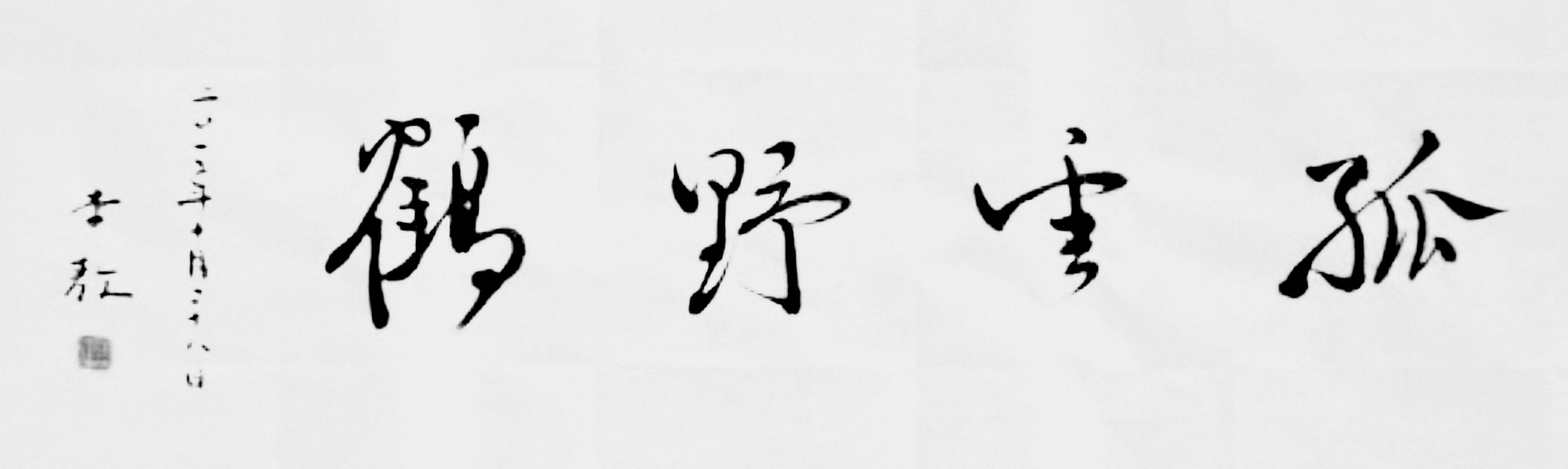

Li was notorious and he had been dubbed the ‘madman’ 狂人 of Taiwan letters. It was a reputation cemented by one of his most oft-quoted statements:

In the last fifty years, and for the last five hundred,

The three greatest writers of vernacular Chinese prose are: Li Ao, Li Ao and Li Ao.

Even the people who disparage me for being boastful

Kowtow to my ancestral tablet in their hearts.五十年來和五百年內,

中國人寫白話文的前三名,是李敖、李敖、李敖。

嘴巴上說我吹牛的人,

心裡都為我供了牌位。

Another example of Li Ao’s style can be found in the introduction to A Monologue on Tradition:

Chinese intellectuals lack a very important quality: independence … the result being that there is no difference between A and B, or C and D. They say the same things, write the same bullshit, and lick the same asses. A, B, C, and D might look a little different, but they’re united in their lack of character and originality…

The tradition is unforgiving when it comes to nonconformity. In other respects Chinese society may be completely inefficient, but when it comes to dealing with the true talents and people of conscience who won’t conform, China is number one; it has a real genius for banning and killing. Individualists share a congenital disinclination to longevity. Most of them die young, and if they’re lucky to live they still find it hard to escape calamity.

It is an insight into Chinese culture made all the more poignant by the fact that Li Ao, who lived to the ripe old age of eighty three, became a caricature of himself, while one of his most pointed critics — the outspoken dissident Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波 — whose views on Li Ao feature below, passed away last year at the relatively young age of sixty two.

***

A famous student of the leading May Fourth-era writer and academic titan Hu Shi 胡適, Li Ao soon achieved notoriety on Taiwan, where he had moved with his family in 1949 (he was born in Harbin in 1935). During the era of Martial Law imposed by the Nationalist Party under Chiang Kai-shek, Li was a garrulous advocate for the freedom of expression, democracy and wholesale Westernization. Although in the United States the Republic of China was lauded as ‘Free China’, its government was quick to punish dissent. Li Ao’s work was frequently banned and he was arrested in the early 1970s for political agitation. Sentenced to ten years jail he was released after only five due to an amnesty announced following Chiang Kai-shek death in 1975.

Free once more this irrepressible ‘madman’ generated a stream of new works, some of which were collected in A Monologue on Tradition (later he churned out a book every few months; his collected works run to forty volumes). I later translated material from it for New Ghosts, Old Dreams: Chinese Voices of Conscience (New York: Times Books, 1992, from which the translations in this essay are taken), edited with Linda Jaivin in the wake of the events of Fourth June 1989.

Li’s coruscating prose read like the next stage in the evolution of the polemical style of the May Fourth Era (1917-1927) yet, despite the gradual cultural opening of the Mainland during the 1980s, it was not until 1989 that Monologue was finally published in Beijing. Years earlier, in 1986, I had met an upcoming literary critic by the name of Liu Xiaobo, he too was known for his ‘madness’ 狂 or ‘craziness’ 癲狂: it’s a term with various, often positive, connotations in the Chinese tradition, and one used by the early twentieth-century writer Lu Xun in the title of his most famous work, ‘A Madman’s Diary’ 狂人日記. Liu’s rambunctious public manner and vitriolic style of writing reminded me of Li Ao and we often discussed the famously prickly Taiwanese contrarian (later, our mutual friend Jin Zhong 金鐘, editor of the Hong Kong journal Open Magazine 開放雜誌, declared that Xiaobo was ‘the Li Ao of the Mainland’). As things unfolded, however, it turned out that in the end neither of these ‘madmen’ had a nice word to say about the other. From 2004, when Li Ao made a debut in the Communist Party controlled media, Liu Xiaobo, by then one of China’s most famous dissidents, was unstinting in his contempt. Li repaid the compliment by reportedly deriding Liu as a ‘dummy’ 笨蛋 who ‘doesn’t even qualify to criticise the Communist Party’ 連登台罵共產黨的資格都沒有!

In the absence of Liu Xiaobo at the time of Li Ao’s death, others stepped into the breach. Writing in his regular online newspaper column Lee Yee, the journalist mentioned above and who remains a clarion voice in Hong Kong, quoted unofficial Mainland opinion:

‘Over ten billion people have time-travelled back to the Ming dynasty [with the virtual enthronement of Xi Jinping as China’s absolute ruler] without a peep [of protest], but just look at the emotional outpourings following the demise of this Literary Lout. It reflects the true state of affairs among China’s thinking people.’ 「十多億人被穿越到明朝卻沒有任何聲音,一個流氓文人去世卻大段大段感喟,實在是自以為讀書人的群體的寫照。」

Following Li Ao’s death many comments posted on the Mainland Internet refer to him as an ‘Old Lout’. I think it’s inappropriate. Now, I’m not expressing any particular respect for the dead Li Ao, but people are complex. As Confucius said, ‘A gentleman does not approve of a person because he expresses a certain opinion, nor does he reject an opinion because it is expressed by a certain person.’ A writer’s oeuvre should be treated like ‘public property’; it shouldn’t be negated holos-bolus just because the person who authored it happens to be odious. 李敖去世,大陸網頁許多評論都以「老流氓」稱之。這不是恰當的評價。並非基於「死者為大」的觀念,而是因為人的一生是複雜的。孔子說,「君子不以人舉言,不以人廢言」。因此作家的著作應該視為「公共財」,不可因其人品而斷然否定。

But some Mainland Netizens conclude that: ‘The problem with Li Ao was that he lived too long. The first half of his life is justly celebrated because he was jailed for opposing Nationalist Party totalitarianism [in Taiwan], but in his later years he betrayed himself when he acted like a Pied Piper for totalitarianism [on the Mainland].’ Others say: ‘On Taiwan he was [like the principled writer] Lu Xun, but on the Mainland he was [like the fawning Mao-era literary lackey] Guo Moruo 郭沫若’; and, ‘Li Ao was vilified in direct proportion to the level of acceptance he enjoyed by the Chinese party-state.’ 大陸網民指他「最大的問題是活得太長了,前半生因反抗國民黨極權繫獄英名流傳,後半生又為某極權充當吹鼓手而晚節不保」;「在台灣是魯迅,在大陸是郭沫若」;「李敖晚年獲得的詛咒與他被大陸主流意識形態所容納的程度成正比。」

— 李怡, 世道人生: 鐵達尼及其他

《蘋果日報》, 2018年3月19日

As Simon Leys noted of Guo Moruo 郭沫若, who was eighty-four — one year older than Li Ao — when he died in 1978: ‘The methodical use of kowtowing is incontestably a recipe for longevity’; and thereby, Guo had acquired ‘a flexibility in his leaping about, a chilling agility in his pirouetting that the most flexible music hall contortionists would have envied him.’

The sobering truth of the matter is that, for all of his early brilliance, Li Ao was a writer-intellectual for whom China was in itself a core faith, a religion. When Taiwan matured into a modern democracy his was but one voice in the everyday din of freedom. His chagrin was palpable. Wealth and power — the century-old dream of national renewal — were in their turn seductive; the China Dream conspired to stifle Li Ao’s voice of conscience. For many illiberal intellectuals he became a reassuring paragon of complicity.

***

In 1965, Li Ao wrote ‘The Art of Survival, a User’s Guide’ 避禍學大綱. A satire about political repression and intellectual life in Taiwan, he said it summed up ‘the art of living in the chaotic world while keeping yourself in one piece’. In it he offered readers fifteen ways ‘to keep your head, stay out of jail, and remain free from the watchful eyes of the authorities’. The last strategy was to ‘be like a flea’. Over half a century later, Li Ao’s advice reads like a comment on his relationship with Liu Xiaobo:

The thing about fleas is that when they bite you it itches but it never really hurts, and they jump away immediately after biting, so the person can never be bothered to catch them. The majority of writers today are like this; they squash a few fleas and they think they’re heroes.

The following essay by Liu Xiaobo was written in 2004. It is one of a number of critiques that he published about a man who was once widely admired by free thinkers in the People’s Republic. For a time in the 1980s these two extraordinary contrarians basked in the same limelight, but in the end one — Li Ao — only truly achieved the stature of a flea, while the other — Liu Xiaobo — matured into a hero of conscience. Here Liu catches the performing flea in the act.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

23 March 2018

Well-honed Hubris

— I have something to say about Li Ao

話說李敖——精明的驕狂

Liu Xiaobo 劉曉波

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

Li Ao is Taiwan’s master of self-promotion. In the 1980s, he enjoyed a period of fame on the Mainland when he was celebrated for his undeniable talent and his unsparing style, as much as for his unbridled literary wildness and vulgarity. Above all, he was appreciated on the Mainland for his unfettered panache, something that was underpinned by his experience as a prisoner of conscience. Since Taiwan evolved into a democracy a man who could enjoyed all the largesse allowed by the freedom of expression revealed that he was a spent force. Recently, he has been beguiled by a belief that Greater China Nationalism is more important than Liberalism. His opposition to Taiwan independence is wrong-headed, he spews oleaginous obfuscations, and he plays up his origins as a Mainlander as he expresses his contempt for local Taiwanese. In particular, since the election of 2000 he has heaped praise on [the Communist Party strategy for controlling Hong Kong and absorbing Taiwan known as] ‘One Country Two Systems’. He’s degenerated, and the higher he hoists the banner of Patriotism, his fall appears all the more precipitous.

最善於自吹自擂的台灣文人李敖,兼具才子的博學和尖刻、文人的狂躁和粗野,曾以良心犯的資歷和狂傲的文字,在八十年代風靡過大陸。然而,自從台灣進入民主社會以來,享受著言論自由的李敖,反而在寫作上露出江郎才盡之態。近年來,從他關於兩岸關係的言論看,他已經陷入大中華民族主義高於自由主義的魔術之中,反台獨反得顛三倒四、滿嘴流油,動不動就以外省人的傲慢貶低台灣本省人。特別是從2000年台灣大選開始,高聲贊美「一國兩制」的李敖一步步地墮落,愛國大旗舉的越高,墮落的就越快。

Like attracts like just as tribes are divided by kind. Phoenix Television is generally called the ‘Hong Kong channel of Chinese Central TV in Beijing’. Of course it is smitten with Li Ao and his support for ‘One Country, Two Systems’. They’ve given him a show all of his own called ‘Li Ao Has Something to Say’. Watching his fawning performance, you realize that in-house intelligentsia of the Chinese Communists now has some serious competition.

物以類聚,人以群分,被稱為中央電視台香港頻道的鳳凰衛視,自然會對贊成「一國兩制」的李敖情有獨鍾,專門開闢《李敖有話說》節目,看李敖的獻媚表演,還真跟中共的御用智囊有一拚。

Li Ao plays up the unfettered craziness of his reputation having declared that he’s the greatest writer China has produced in 5000 years, but he’s not so crazy as to negate everything. He has the finely honed skills of a politician and he trims his sails to the wind; he has a Fingerspitzengefühl for knowing just what to say when and how to say it with ultimate finesse. Faced with the powers-that-be on Taiwan — whether it be during the rule of the Chiang Family, or under the presidency of Lee Teng-hui [from 1988 to 2000] or Ch’en Shui-pien [from 2000 to 2008], he mercilessly trashes all politicians and celebrities, without exception and without compunction, what’s more he does it with unbridled glee, dumping shitloads of foulness on them. But when faced with the power-holders on the Mainland and high-level cadres, he’s a study in moderation and sincerity; he oozes flattery. When he does venture some criticism it is carefully honed to avoid giving offense; he’s a model of good manners and measured behavior.

李敖是很癲狂,自稱五百年來中文寫作第一,但他並非癲狂得目無一切,面對不同的對象,他表現出一種政客式的精明,拿捏分寸和把玩辭藻的技巧,可謂爐火純青:對台灣政權,無論是蔣家時代還是李登輝、陳水扁的時代,他罵遍了台灣的政客和名流,且罵得百無忌憚、心花怒放、臟話跌出;而一旦面對大陸政權及其高官,他馬上變得溫柔敦厚、語帶媚腔,偶有批評,也是避重就輕,很禮貌很分寸。

Li Ao has repeatedly denounced the White Terror of the Chiang era; he has decried Lee Teng-hui as a traitor, a cheat and a man who sells out his family. As for Ch’en Shui-pien [president on Taiwan at the time of writing]: he’s nothing but a ‘slave in the service of the slaves of slaves’, a ‘tooth-pick-hawking Hitler’. Although, regard to this last remark he’s quick to add: ‘Here I must apologise to Hitler since at least he was capable; after all, he nearly conquered the whole world, but here on Taiwan Ch’en Shui-pien is nothing more than a useless tramp.’ He decries Taiwan’s phony democracy: Ch’en Shui-pien got into power not by inheriting a throne or as a result of military valor; he doesn’t serve the people nor was he democratically elected; he’s nothing but a swindler: ‘All the leaders of Taiwan rely on one thing and one thing only: deception… . From Ch’en Shui-pian down, they’ve got into power through trickery.’ (from Episode 1, 8 March 2004.) What he fails to explain is just how someone like him, Li Ao, can get away with saying the most outrageous garbage without having to worry about the consequences? How come he could mount a presidential challenge in the year 2000? Nor can he explain how it is that internationally the majority of democratic nations acknowledge that Taiwan is indeed a democracy? The truth of the matter is that he calls Taiwan a ‘sham democracy’, a ‘scam’ because people didn’t vote for him and elected someone he despises instead.

他反覆抨擊蔣家政權的恐怖統治,他罵李登輝是叛徒、騙子、認賊作父,罵陳水扁是「給奴才做奴才的奴才」,把陳水扁貶為「賣牙簽的希特勒」,甚至說「我講到這裡先向希特勒抱歉。因為希特勒他是能幹的人,幾乎統治了這個世界,可是這個陳水扁在台灣像個癟三一樣,甚麼都不能做。」 他大罵台灣是假民主,說陳水扁上台,靠的不是皇權時代的繼承、不是戰功、不是為民服務、也不是民主選舉,而是靠騙:「整個台灣的領導人……他們就靠了一個字就是騙。……從陳水扁以下這批人,他們得到政權是靠一個騙字。」(第一集《我終於有一個機會在這裡拋頭露面》 3月8日)但他卻不解釋為甚麼在假民主的台灣,他李敖可以胡說八道而無後顧之憂?還可以在2000年作為總統候選人參選?也不解釋為甚麼絕大多數民主國家都承認台灣已經是民主社會?難道只因李敖選不上或他討厭的人當選,就是假民主,就是「騙」!

However, when Li Ao turns his gaze to the Chinese Communists and their privileged elite he rejects Taiwan democracy in favor of Mainland autocracy. He plays the apologist for the follies of the Mao era and extols Mao as an example of a true political leader. He even excuses the Butchers of the Fourth of June [1989] and expresses his admiration for Deng Xiaoping, a politician who weathered three falls from power and three political rehabilitations. When he speaks of the US President Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping meeting [in 1979], he calls Carter a hypocrite for saying that China doesn’t allow the freedom of movement and is lacking both in democracy and freedom; but he has nothing but praise for Deng Xiaoping’s raffish response: ‘Democracy and freedom, then. How many people do you want us to send over to you? One or two million, or I can give you 10 to 20 million: will you take them?’

然而,談到中共政權及其權貴,他卻屢屢為獨裁政權打壓台灣背書,公開為毛澤東時代的荒謬辯護,把暴君毛澤東奉為第一流政治家;他還為六四大屠殺的劊子手辯護,聲言「佩服那個三起三落的鄧小平」。他談到美國總統卡特和鄧小平見面時,說卡特是偽君子,因為他批評中國沒有遷移自由是不民主不自由;卻誇鄧小平近乎無賴的回答:「我們民主啊自由啊,你要多少人我送給你,你要一百萬兩百萬,一千萬兩千萬我送給你,你要不要?」

It was obvious that Jimmy Carter was talking about freedom of movement within China, and not immigration to the USA. Deng knew that full well, but he had no good response yet he needed to save face and that’s why he muddied the waters in that way. Li Ao’s interpretation is even more shameless: ‘Fuck it: you don’t even want one, you say what you will and expect us to suck it up, and how are we supposed to cope?’ (Episode 14)

顯然,卡特說的遷移自由和移民美國完全是兩碼事,鄧小平自知理虧又要面子,也就只能胡攪蠻纏。李敖評論比鄧小平的回答更無賴:「他媽的你一個都不接,一個都不要,你講風涼話叫我們來承受,我們怎麼受的了呀?」(《由「棄」字識破風涼話》3月25日 第14集)

Li Ao also talks about the freedom of expression. Here he is particularly enamored by his own heroic struggles for free speech in Taiwan. However, as soon as the focus turns to the Mainland he becomes quite the sophist. He never mentions the Mainland censorship system or the frequency with which books are banned or anything about the persecution of writers. He’s positively tolerant when considering the lack of freedom of expression on the Mainland. Even when Phoenix TV censors him Li Ao’s response is one of sympathy. The contrast between this and his cutting outrage in denouncing censorship during the era of Martial Law on Taiwan couldn’t be greater.

李敖也會談到言論自由,特別愛談他當年在台灣爭取言論自由的壯舉,但一涉及大陸的言論自由問題,他就談得分外精明。他從不提及大陸的言論管制以及頻繁發生的禁書案和文字獄,他還寬容地對待大陸的言論不自由,就連鳳凰衛視刪節他的講話,他都能報以理解的態度。這與他斥責蔣家政權禁書時的尖刻和憤怒,恰成鮮明的對比。

Someone asks him: If you had stayed on the Mainland and lived during the Cultural Revolution would you dare say things like this? Why do you only attack Taiwan don’t dare cuss the Mainland? His reply is cunning, suddenly he’s no longer the self-proclaimed hero and openly admits his craven attitude:

當別人問他:如果你生在大陸、遭遇文革,你敢講這些話嗎?你為甚麼只敢罵台灣而不敢罵大陸?他的回答很狡猾,一反總是自稱英雄的習慣,公開承認自己懦弱:

There’s times when you’re just going to be a wimp. … When I recall how I dealt with my incarceration I know I’d treat everything like it was a joke, I’d transcend the moment, I’d be sly and deceptive, and I’d use trickery to avoid being caught up in the disaster. You don’t need to speculate about what I, Li Ao, would have done if I’d stayed on the Mainland: I might have done some underhanded things, or I might have done a few little surprising things. Who’s to say? You can never respond to a counter factual scenario.’ (Episode 31, 19 April 2004)

「人難免有變得無賴的時候,……我今天回想到當年我坐牛棚的時代,我記得我會用一種玩世的方法,逃世的方法,狡猾的方法,技巧的方法來躲過那一劫。所以大家不要假設,我李敖如果留在大陸我做甚麼,我可能做出一些很卑微的事情來,也能做一些小小的驚天動地的事情來,誰知道呢,這種假設的問題永遠沒有答案。」(4月19日第31集《假如問題永遠沒有答案》)

In reality, Li Ao provided an answer in ‘Li Ao Has Something to Say’ for Phoenix Television. Carefully crafted and double-faced, it was an example of how a person can tailor their speech to suit an audience. That’s also the normal state of affairs for patriots on the Mainland today.

其實,鳳凰衛視的「李敖有話說」已經給出了答案:技巧而狡猾地「見人說人話,見鬼說鬼話。」而這,正是當下大陸愛國者們的言行常態。

23 April 2004, Beijing

2004年4月23日于北京家中

Sources:

- Geremie R. Barmé and Liu Xiaobo, A Madman’s End, Los Angeles Review of Books China Channel, 30 March 2018

- 劉曉波, 話說李敖——精明的驕狂, 2004年4月23日

Further Reading:

- 劉曉波, 狂妄成精的李敖, 2005年9月20日

- 劉曉波, 李敖不過是統戰玩具, 2005年9月29日

- 李敖廈大演講 批魯迅、劉曉波, 2011年4月3日

- Geremie R. Barmé, Mourning, China Heritage, 30 June 2017

- 曹長青, 李敖是邪門之典型, 後半生只做對一件事: 死了!, 2018年3月18日