Xu Zhangrun vs. Tsinghua University

Voices of Protest & Resistance (XVI)

Tsinghua University formally celebrated its 108th anniversary on the 28th of April 2019. Grand ceremonies involving prominent government officials, local and international dignitaries and hand-picked scholars and students were hosted by the Communist Party leaders of the university. The visitors were fêted and duly impressed by the achievements, and the grandiosity, of one of the preeminent educational institutions in the People’s Republic of China.

At one controversial nook of the campus, however, a group of Tsinghua scholars, older graduates and supporters gathered to pay their respects to two of the famed Four Pre-eminent Sinologists of Tsinghua 清華國學四大導師, Wang Guowei (王國維, 1877-1927) and Chen Yinque (陳寅恪, 1890-1969, aka Chen Yinke). (The other two scholars are Liang Qichao 梁啟超 and Yuan-jen Chao 趙元任.)

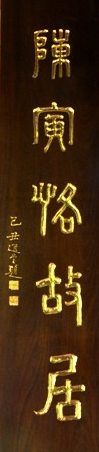

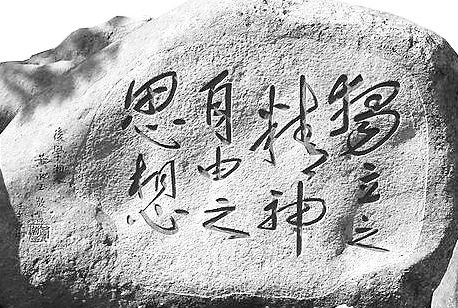

These two academics are celebrated on the Tsinghua campus in a little grove where a large stone stele was erected in 1929 to commemorate Wang Guowei, who had drowned himself two years earlier. The stele bears an epitaph composed by Chen Yinque, one of China’s most famous modern historians, who died in ignominious circumstances forty years later, in 1969.

The encomium that Chen wrote for his dead colleague remains one of the most frequently quoted pieces of writing related to the crisis of academic freedom in China today. Although Tsinghua University has boasted of the Wang Guowei Stele since it was re-erected in 1985 (toppled in the early Cultural Revolution, it was used as a laboratory bench in the faculty of science for nearly two decades), it is also an embarrassment to an administration that is active in persecuting intellectual independence and academic freedom.

Since 1949, Tsinghua University has been haunted by the spirits of long-dead scholars like Wang Guowei and Chen Yinque.

***

Below we offer a translation of the Wang Guowei Stele, Chen Yinque’s 1953 reaffirmation of the principles he articulates in the Epitaph he wrote for the Wang Stele and a simple pictorial account of the unofficial commemoration of their memory, and their spirit, held in the face of official displeasure on Sunday 28 April 2019, and the aftermath on 30 April.

My thanks to Warren Sun 孫萬國 for checking the translation of the Wang Guowei Epitaph and for offering a number of timely suggestions.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

28 April 2019

The 108th Anniversary of the

Founding of Tsinghua University

The 90th Year Since the

Wang Jingwei Stele was First Erected &

Fifty Years After the Death of Chen Yinque

Updated on 1 May 2019

***

Further Reading:

- Guo Yuhua 郭於華, ‘J’accuse, Tsinghua University!’, China Heritage, 27 March 2019

- Xu Zhangrun and Guo Yuhua speak to Voice of America 美國之音 about ‘The Death of the Tsinghua Spirit’, YouTube, 29 April 2019 (in Chinese)

- Boxun 博訊, 清华校友呼唤“独立之精神,自由之思想”, 30 April 2019

- The Xu Zhangrun Archive, China Heritage, 1 August 2018-

***

An Epitaph for Master Wang of Haining

《海寧王先生之碑銘》

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

In the summer 1929, when the Tsinghua Sinology Research Institute was closed [after only four years in existence — trans.], its teachers and students subscribed to a fund to erect this memorial stele in honour of an outstanding scholar [Wang Guowei, who committed suicide on 3 June 1927]. Professor Chen Yinque composed the following epitaph:

1929年夏,清華國學院停辦,該院師生為紀念這位傑出的學者,募款修造了這座紀念碑。碑文為陳寅恪教授所撰,其文曰:

In the two years since Master Wang Jing’an of Haining [Wang Guowei] drowned himself, the scholars of Tsinghua [Sinological] Research Institute have been at a loss as how to requite their longing. Students nurtured and trained by him over those years felt compelled to commemorate his memory in a lasting fashion and therefore determined to erect an inscribed stele that would preserve his memory for the edification of all, as well those in the future. Collectively they reasoned that it would be best to inscribe their sentiments in adamantine stone, thereby manifesting their respect to the world in perpetuity. They approached me [Yinque] with a request to compose an inscription; I repeatedly made to decline this honour. Herewith, I can touch on [but a scant few of] the achievements and aspirations of this Gentleman. In so doing, however, I hope to inspire all who come after us. Herewith my words:

海甯王靜安先生自沈後二年,清華研究院同仁咸懷思不能自已。其弟子受先生之陶冶煦育者有年,尤思有以永其念。僉曰,宜銘之貞瑉,以昭示於無竟。因以刻石之詞命寅恪,數辭不獲已,謹舉先生之志事,以普告天下後世。其詞曰:

In the pursuit of learning a True Scholar breaks the shackles of mundane values, for only thereby can he pursue the Truth. [This Man, Wang Guowei,] chose to die rather than live on with his mind imprisoned. This, then, is the heart of the matter: this spirit of sacrifice [for the sake of free thought] is shared by all Outstanding and Sagacious individuals, be they in the past or alive today. How can Common Folk hope to understand such things?

It is through his death that This Man demonstrated an independent and free mind. His act was not occasioned by mere personal grievance [rumours at the time suggested Wang had committed suicide as a result of a dispute with the scholar Luo Zhenyu, his financial patron and later relative — Wang’s son married Luo’s daughter], nor was it driven by dynastic collapse [another story in circulation held that he had pledged undying loyalty to Xuantong — Aisin Gioro Puyi, the last emperor of the defunct Qing dynasty]. It is in a mood of deep mourning that we have erected this stele near his lecture hall, expressing hereby our boundless sense of loss. And this stele represents the extraordinary qualities of this Gentleman, one whose spirit is forever vouchsafed to Vast Heaven Above.

The future cannot be known; indeed there may come a time when this Gentleman’s work no longer enjoys preeminence, just as there are aspects of his scholarship that invite disputation. Yet his was an Independent Spirit and his a Mind Unfettered — these will survive the millennia to share the longevity of Heaven and Earth, shining for eternity as do the Sun, the Moon and the very Stars themselves.

士之讀書治學,蓋將以脫心志於俗諦之桎梏,真理因得以發揚。思想而不自由,毋寧死耳。斯古今仁聖同殉之精義,夫豈庸鄙之敢望。先生以一死見其獨立自由之意志,非所論於一人之恩怨,一姓之興亡。嗚呼!樹茲石於講舍,系哀思而不忘。表哲人之奇節,訴真宰之茫茫。來世不可知者也,先生之著述,或有時而不彰。先生之學說,或有時而可商。惟此獨立之精神,自由之思想,曆千萬祀,與天壤而同久,共三光而永光。

Text by Chen Yinque of Yining [Jiangxi province]

Calligraphy by Lin Zhijun of Min county [Fujian province]

Seal script headstone by Ma Heng of Yin county [Zhejiang province]Stele design by Liang Sicheng of Xinhui [Guangdong province]

Construction overseen by Liu Nance of Wujin [Jiangsu province]

Headstone and epitaph carved by Li Guizao of Beiping [Beijing]The Teachers and Students of the Sinological Research Institute of National Tsinghua Univeristy respectfully erected this epitaph

On the Third Day of the Sixth Month of the Eighteenth Year of the Republic of China [3 June 1929]

Marking the Second Anniversary [of Wang Guowei’s demise]義寧陳寅恪撰文 閩縣林志鈞書丹 鄞縣馬衡篆額

新會梁思成擬式 武進劉南策建工 北平李桂藻刻石

中華民國十八年六月三日二週年忌日 國立清華大學研究院師生敬立

Chen Yinque — Fulfillment & Denouement

Chen Yinque went on to achieve fame both as an historian and as a gifted linguist. In the late 1940s, he was forced to decline an invitation to take up a professorship at Oxford University due to failing eyesight and general ill health. Instead he was he remained on the Mainland where he was employed at a university in Guangzhou. During the early years of the People’s Republic he witnessed the Party’s re-organisation of the nation’s universities and the Thought Re-education Campaign launched in the early 1950s that devastated — and continues to devastate — China’s intellectual life (for details, see our series Drop Your Pants! (China Heritage, 8 August-1 October 2018).

In late 1953, Chen Yinque was offered a position as head of the Second History Research Institute at the Academia Sinica, a prestigious pre-revolutionary body of scholars that the Communist Party recreated in Beijing in its own image after the original academy, along with many leading scholars, relocated to Taiwan in the late 1940s. The reasons why he declined what for the time would have seemed like an irresistible invitation were not made public until decades after his death. Although sanctioned by none other than Mao Zedong, the job offer itself came from Guo Moruo (郭沫若, 1892-1978), a noted academic and May Fourth-era literary figure who was also a notoriously sycophantic fellow traveller (he subsequently joined the Party).

***

My Reply to Academia Sinica

《對科學院的答復》

Translated by Geremie R. Barmé

In the Epitaph I composed for the Wang Guowei Commemorative Stele [at Tsinghua University in 1929] I was quite clear in stating my intellectual stance and academic approach. Following Wang Guowei’s death I had been approached by a group of students led by Liu Jie. At the time [I wrote the Epitaph] the Nationalist Party had recently unified China, and you can check the stele itself to confirm the exact date. Anyway, Luo Jialun was president of Tsinghua at the time and it was widely known that he belonged to the Central Club Clique of the Nationalists [the right-wing faction of the party close to Chiang Kai-shek], and I was only a lecturer in the Research Institute of the university. I regarded Wang Guowei to be the most important Chinese academic of his day so I wrote an encomium in the hope that I could convey a sense of this to the world at large, as well as to the future, and in particular to all students of history.

It remains my belief that the most important qualities for a scholar to possess are intellectual freedom and an independent spirit. That’s why I said in my Encomium:

In the pursuit of learning a True Scholar breaks the shackles of mundane values, for only thereby can he pursue the Truth.

My formulation ‘Mundane Values’ was a reference to Sun Yat-sen’s Three Principles of the People. One can only pursue Truth if one has broken free of such shackles. If you are bound by such shackles you will enjoy neither intellectual independence nor the sense of a free spirit; therefore, the Truth will be unobtainable nor, for that matter, will real scholarship be possible. Now, as to the actual quality of one’s scholarship that should always be open to debate, just as I observed in regard to Wang Guowei’s own achievement [where I wrote: ‘there may come a time when this Gentleman’s work no longer enjoys preeminence, just as there are aspects of his scholarship that invite disputation’]. My work contains errors and it too is open to disputation. Intellectual disagreements between people are inevitable and no one should take particular offense. Both you and I should be open to this.

In that long poem I wrote about Wang Guowei, for example, I was critical of Liang Qichao. When I showed it to Master Liang he merely chuckled and took no offense. I was also critical of Hu Shi. However, when it comes to my advocacy of intellectual independence and the need for a free spirit I am unwavering. That’s why I concluded my Epitaph with the words:

Yet his was an Independent Spirit and his a Mind Unfettered — these will survive the millennia to share the longevity of Heaven and Earth, shining for eternity as do the Sun, the Moon and the very Stars themselves.

我的思想,我的主張完全見於我所寫的王國維紀念碑中。王國維死後,學生劉節等請我撰文紀念。當時正值國民黨統一時,立碑時間有年月可查。在當時,清華校長是羅家倫,他是二陳(CC)派去的,眾所周知。我當時是清華研究院導師,認為王國維是近世學術界最主要的人物,故撰文來昭示天下後世研究學問的人。特別是研究史學的人。我認為研究學術,最主要的是要具有自由的意志和獨立的精神。所以我說「士之讀書治學,蓋將以脫心志於俗諦之桎梏」。「俗諦」在當時即指三民主義而言。必須脫掉「俗諦之桎梏」,真理才能發揮,受「俗諦之桎梏」,沒有自由思想,沒有獨立精神,即不能發揚真理,即不能研究學術。學說有無錯誤,這是可以商量的,我對於王國維即是如此。王國維的學說中,也有錯的,如關於蒙古史上的一些問題,我認為就可以商量。我的學說也有錯誤,也可以商量,個人之間的爭吵,不必芥蒂。我、你都應該如此。我寫王國維的詩,中間罵了梁任公,給梁任公看,梁任公只笑了一笑,不以為芥蒂。我對胡適也罵過。但對於獨立精神,自由思想,我認為是最重要的,所以我說「唯此獨立之精神,自由之思想,歷千萬祀與天壤而同久,共三光而永光」。

I do not believe that Wang Guowei killed himself due to a personal grievance with Luo Zhenyu, nor was it about the collapse of the Manchu-Qing dynasty. Rather, I believe that he felt through his death he was offering a validation of his undaunted will. To achieve a truly independent spirit and real free will requires a struggle, it is in fact a life-and-death struggle. Again, as I wrote in the Epitaph:

[This Man, Wang Guowei,] chose to die rather than live on with his mind imprisoned. This, then, is the heart of the matter: this spirit of sacrifice [for the sake of free thought] is shared by all Outstanding and Sagacious individuals, be they in the past or alive today. How can Common Folk hope to understand such things?

Other things are of minor consequence, this, however, remains of the greatest importance. The principles I articulated in that Epitaph are ones to which I adhere steadfastly to this day.

我認為王國維之死,不關與羅振玉之恩怨,不關與滿清之滅亡,其一死,乃以見其獨立之意志。獨立精神和自由意志是必須爭的,且須以生死力爭。正如詞文所示,「思想而不自由,毋寧死耳。斯古今仁賢所同殉之精義,夫豈庸鄙之敢望。」一切都是小事,惟此是大事。碑文中所持之宗旨,至今並未改易。

I absolutely do not oppose the present political regime. However, I read Das Kapital in Switzerland during the Third Year of Xuantong [1911-1912, at the time of the collapse of the Qing dynasty and the founding of the Republic of China] and I concluded that if one accepted the Marxist-Leninist worldview it would not be possible to pursue scholastic research. [If I were to run the institute which I am being invited to head up] Everyone that I invited to work there, and all of my own students [disciples] would have to be able to feel intellectually independent and free of spirit. Otherwise, they simply cannot possibly be students of mine. I have no idea whether, in the past, you really shared my views, but [it is evident that] you definitely don’t do so now. I can no longer recognise you as a student of mine. Whether it be Zhou Yiliang or Wang Yongxing, if they share my understanding then they are indeed still my students, otherwise they simply are not. It will be the same in regard to any students I might take on in the future.

That is why I must articulate an initial condition [related to the invitation from Beijing]:

The History of the Middle Ages Research Institute must be allowed to be free of Marxism-Leninism and not be required to undertake political study [that is the imposed and regular study of Party dogma and policy].

What I mean by this is that no shackles are to be imposed upon us; you simply can’t start out with Marxism-Leninism and expect people to pursue real scholarship. Anyway, there’s no need for constant political study sessions. Naturally, I would require that this stipulation not only apply to me, it would also have to apply to everyone in my research institute. I have never engaged in political discussions and I have nothing to do with politics, let alone any political party or faction. You can investigate my history as much as you like, but I assure you that you’ll find that this is indeed the case.

我決不反對現在政權,在宣統三年時就在瑞士讀過資本論原文。但是,我認為不能先存馬列主義的見解,再研究學術。我要請的人,要帶的徒弟都要有自由思想,獨立精神。不是這樣,即不是我的學生。你以前的看法是否和我相同我不知道,但現在不同了,你已不是我的學生了。所有周一良也好,王永興也好,從我之說即是我的學生,否則即不是。將來我要帶徒弟,也是如此。因此,我又提出第一條:「允許中古史研究所不宗奉馬列主義,並不學習政治。」其意就在不要桎梏,不要先有馬列主義的見解,再研究學術,也不要學政治。不止我一人要如此,我要全部的人都如此。我從來不談政治,與政治決無連涉,和任何黨派沒有關係。怎樣調查,也只是這樣。

And this is why I have another precondition:

I formally request that Master Mao [Zedong] and Master Liu [Shaoqi] provide me with a formal, signed letter of permission which I can use to shield myself.

I address this request to them because Master Mao is the supreme political authority in China and Liu Shaoqi is the most important person in charge of the [Communist] Party. I can only hope that these lofty figures share my understanding of matters and will be willing to comply with my suggestions, otherwise there’s no further need to discuss the pursuit of scholarship.

因此,我又提出第二條:「請毛公或劉公給一允許證明書,以作擋箭牌。」其意是毛公是政治上最高當局,劉少奇是黨的最高負責人。我認為最高當局也應有同樣看法,應從我之說,否則,就談不到學術研究。

My situation is simple: I can just as readily stay put [here in Guangzhou] instead of going to the bother of making such a move [north to Beijing]. As for the pre-conditions I have outlined here, of course Academia Sinica will face a dilemma: it won’t look good if they accept my requests nor indeed if they reject them. Life here in Guangzhou is peaceful and I can pursue my research without any such thorny issues. If I were to relocate to Beijing then there would be problems. The move itself would be a challenge since I suffer from ill health: I have high blood pressure and my wife has an enlarged heart. She was coughing up blood only yesterday.

至如實際情形,則一動不如一靜,我提出的條件,科學院接受也不好,不接受也不好。兩難。我在廣州很安靜,做我的研究工作,無此兩難。去北京則有此兩難。動也有困難。我自己身體不好,患高血壓,太太又病,心臟擴大,昨天還吐血。

I require that you convey my views to Academia Sinica exactly as I have expressed them here, with no additions or deletions. You can also take along a copy of the [Wang Guowei] Epitaph for [the head of the Communist Party’s reinvented Academia Sinica] Guo Moruo to read. [I believe that] Guo has read the poems I wrote mourning Wang Guowei, but I have no idea if the Stele still exists [at Tsinghua University]. If, in their opinion, what I wrote for it is now found to be erroneous then they can simply destroy it and Guo can come up with something himself. Perhaps that would be more suitable. After all, Guo Moruo is an Oracle Bone specialist [as was Wang Guowei], one of the ‘Four Studios’ in fact [‘Four Studios’ was a short-hand expression for the four leading Oracle Bone scholars of the Republican era: Luo Zhenyu 羅振玉, whose literary name or ‘style’ 號 was ‘Snow Studio’ 雪堂, Wang Guowei 王國維, or the ‘Studio for Observing’ 觀堂, Guo Moruo 郭沫若, known as ‘Cauldron Studio’ 鼎堂 and Dong Zuobin 董作賓 whose sobriquet was ‘Learned Studio’ 彦堂], so he may well have a more in-depth understanding of Wang Guowei’s scholarship than me. In that case, I can play [the great Tang prose master and upright Confucian] Han Yu to Guo’s God of Learning. Moreover, let me suggest that if others wish to turn their hand to writing poems [about Wang Guowei] they should by all means do so, perhaps most suitably in the manner of Li Shangyin [that is, in a highly allusive style laden with literary references].

Anyway, the Epitaph I composed is well known, nothing can bury it now.

— Oral remarks made by Chen Yinque and

recorded by Wang Jian on 1 December 1953.

A transcript is deposited in the

archives of Zhongshan University

你要把我的意見不多也不少地帶到科學院。碑文帶去給郭沫若看。郭沫若在日本曾看到我的[輓]王國維詩。碑是否還在,我不知道。如果做得不好,可以打掉,請郭沫若來做,也許更好。郭沫若是甲骨文專家,是「四堂」之一,也許更懂得王國維的學說。那麼我就做韓愈,郭沫若就做文昌,如果有人再做詩,他就做李商隱也很好。我[寫]的碑文,已經傳出去,不會湮沒。

— 陳寅恪口述,汪篯記錄

一九五三年十二月一日。

副本存中山大學檔案館

During the 1950s and early 1960s, Chen was protected both by Tao Zhu (陶鑄, 1908-1969), the solicitous Party boss of Guangdong province, as well as by various Beijing leaders who, despite everything, thought of themselves as ‘friends of the intelligentsia’, including Zhou Enlai and the prominent ideologue Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, who frequently features in the pages of China Heritage. When Tao fell from grace in the early stages of the Cultural Revolution, Chen was quickly subjected to virulent Red Guard denunciations. After three years of political torment, both he and his wife Tang Yun (唐篔, 1898-1969), life companion, scholastic support and devoted amanuensis, succumbed to prolonged illnesses in 1969.

***

The Abiding Spirit of Wang Guowei & Chen Yinque

Tsinghua University, April 2019

A Photographic Account

‘Today, we are all Xu Zhangrun!’

‘今天我們都是許章潤!’

— a remark made to Xu Zhangrun by many of those who visited

the Wang Guowei Stele at Tsinghua Univeristy on 28 April 2019

On the eve of celebrations marking the 108th anniversary of Tsinghua, the authorities erected a barrier around the Wang Guowei Commemorative Stele, ostensibly as part of a project to pave the area. Although Professor Xu Zhangrun and other scholars and Tsinghua graduates were prevented from holding a gathering at the stele where they hoped to express their respects for the long-dead Grand Masters and present floral tributes, officials gave tacit permission for ground workers to allow the pilgrims to approach the Stele either alone or in groups of two, thus avoiding a confrontation or claims that the agèd visitors were ‘amassing a crowd to create public affray’ 聚眾鬧事.

— The Editor

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

***

Envoi

In Beijing, many people who saw this modest series of photographs observed wistfully:

只見白頭翁,不見黑髮人。

There’s grey-haired worthies aplenty,

But such a dearth of dark-haired youth!

One of the most famous monuments to freedom of thought and the independent spirit is located on the grounds of Tsinghua University, the institution where Xu Zhangrun, teaches. It is etched on a stele set up to commemorate the scholar Wang Guowei (王國維, 1877-1927), who committed suicide in 1927. The inscription on the stele was written by Chen Yinque (陳寅恪, 1890-1969), a major historian who survived into the People’s Republic only to die in the Cultural Revolution. Chen’s life itself was a monument to principled scholarship, and he remained a conscientious objector to the end.

— from the Translator’s Postscript to Xu Zhangrun 許章潤

And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!

China Heritage, 10 November 2018

Update

1 May 2019

As we have noted in the above, on 25 April 2019, the Party leaders of Tsinghua University arranged for a blue, prefabricated metal barrier to encircle the Wang Guowei Commemorative Stele with an Epitaph by Chen Yinque as a ‘political cordon sanitaire’. A reason for the unexpected barrier was readily forthcoming: ground works were urgently required to replace the brick paving around the Stele with a more burnished surface. It was merely a coincidence that the necessary ‘security structure’ also happened to prevent Tsinghua scholars, graduates and others from gathering at the Stele on the occasion of the 108th anniversary of the founding of Tsinghua, a university that, in more enlightened times, has boasted of Wang, Chen and independent scholars like them.

In the photographic album presented here we record the fact that dignified protesters bearing floral tributes for the two long-dead scholars gathered outside the Blue Wall. They were allowed in to the enclosure one or two at a time to offer their flowers and express their mourning for the lingering spectre of ‘intellectual independence and free hearts’ at Tsinghua University.

Once the authorities had calculated that the clear and present danger represented by a modest group of older academics, writers and Tsinghua graduates had passed, the Blue Wall around the Wang/ Chen Stele was dismantled. The following photographs were taken on 30 April, and they are followed by a satirical poetic couplet composed by a Tsinghua graduate:

A Poetic Door Couplet

Left vertical: Renovations, not before nor after, coinciding with the university’s commemoration. You found it brick and left it stone

上聯:早不修,晚不修,偏偏校慶期間修,地磚換石頭。

Right vertical: Boastful Confidence, it’s not here, it’s not there; even you don’t believe it. You came in pride yet end up ridiculed

下聯:這自信,那自信,說了自己也不信,早晚成笑柄。

Cross comment: Fools Create Problems for Themselves

橫批:庸人自擾

— an anonymous Tsinghua graduate

***

***