獨夫之心 日益驕固

The title of this essay is taken from a line in one of the most famous poems in the Chinese tradition related to the overweening autocrat and thwarted imperial ambition. ‘The Great Ch’in Palace, a Rhapsody’ was written by the Tang-dynasty poet Du Mu (杜牧, 803-852) in 825 CE. Taking as its theme the sacking of the Epang Palace 阿房宮 on the outskirts of Xianyang, the Qin capital, in 207 BCE. The vast, unfinished palace of Qin Shihuang, literally ‘the first emperor fo the Qin’, and its destruction by an army of rebels were, until the rise of the Chinese Communists in the 1930s, regarded throughout Chinese history as a symbol both of the hauteur of empire and the inevitable fate of cruel rulers. (Mao Zedong, who delighted in ‘going against the tide’ in many regards, praised the First Emperor. At the height of his powers in the late 1950s, Mao was, to use a common expression, like ‘Karl Marx plus Qin Shihuang’ 馬克思加秦始皇).

From early 2019 to early 2020, Du Mu’s poem, one written nearly 1,200 years ago, resonated in Chinese life once again, and in unexpected ways. Some of the themes of Du Mu’s poem — popular fury, frustrated ambition and the hubris of the autocrat — would link Xu Zhangrun, a famously outspoken professor of law, with Xi Jinping, and both of them to the citizen journalist Li Zehua, who disappeared on 26 February 2020.

The following essay is our latest ‘Lesson in New Sinology’, as well as being part of a modest series titled ‘Viral Alarm’ that is related to the 2020 coronavirus epidemic. It also develops our long-term theme of translatio imperii sinici, or ‘the creative adaptation of imperial Chinese traditions’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

10 March 2020

***

***

Related Material

Viral Alarm:

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘Viral Alarm: When Fury Overcomes Fear’, ChinaFile, 10 February 2020 (Chinese original: 許章潤, ‘憤怒的人民已不再恐惧’, Matters, 2020年2月4日; or, read a parallel-text version here)

- ‘2019-nCoV — A Teaching Moment, Spring Term 2020’, China Heritage, 12 February 2020

- Staff, ‘The Li Wenliang Storm’, China Media Project, 18 February 2020

- Xu Zhiyong 許志永, ‘Dear Chairman Xi, It’s Time for You to Go’, ChinaFile, 26 February 2020 (Chinese original: 許志永, ‘勸退書’, 《公民》, 2020年2月4日)

- Guo Yuhua 郭於華, ‘The Poison in China’s System’, China Heritage, 7 March 2020

- Ren Zhiqiang 任志強 (attributed), ‘Ren Zhiqiang’s “Denunciation of Xi Jinping: stripping the clothes of a clown who is determined to be emperor’ ‘任志强“讨习檄文”:剥光了衣服坚持当皇帝的小丑’,《新世纪》, 2020年3月6日 (for a partial translation, see Josh Rudolph, ‘Essay by Missing Property Tycoon Ren Zhiqiang’, China Digital Times, 13 March 2020)

- Zhao Shilin 趙士林, ‘Gengzi Memorial to the Throne’, ‘庚子上書’, 《中國數字時代》, 2020年3月9日

Chen Qiushi:

- Cindy, ‘Lawyer Chen Qiushi’s Video Diary of Hong Kong Visit’, China Digital Times, 23 August 2019

- Vivian Wang, ‘They Documented the Coronavirus Crisis in Wuhan. Then They Vanished.‘, The New York Times, 15 February 2020

- Jiayang Fan, ‘Mr Chen Goes to Wuhan’, This American Life, 28 February 2020

- S. Ling, ‘Online petition calls for White House to save two missing Chinese reporters’, The Online Citizen, 4 March 2020

Li Zehua:

- Kcriss Li 李澤華 videos on YouTube

- 視頻:公民記者李澤華在武漢被捕前45分鐘全過程 (The last 45 minutes before the citizen journalist Li Zehua was arrested 2/26), YouTube, 26 February 2020

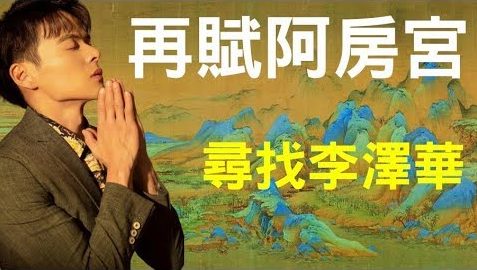

- 老北京茶館 #258, ‘再賦阿房宮——尋找李澤華陈秋實方斌’, 2020年2月28

- Staff, ‘Opening the Door’, China Media Project, 28 February 2020

***

Xi Jinping’s Scorecard

General Party Secretary Xi himself declared that:

‘Our struggle against the coronavirus epidemic is a major test both for our system of government and for our governance capabilities.’

Regretfully, I must point out that you got exactly ZERO marks for the first assignment in this major test.

習總書記說:「這次抗擊新冠肺炎疫情,是對國家治理體系和治理能力的一次大考。」

不能不遺憾地指出,這次大考第一張試卷,只能打零分。

— from Zhao Shilin’s ‘Gengzi Memorial to the Throne’

庚子上書, 《中國數字時代》, 2020年3月9日

Closed Mouths, Forbidden Speech

封口禁言

‘Silent China and its enemies’ is a topic to which we return time and again. It concerns the efforts of the Chinese state, its agencies and affiliates, be they in- or outside the People’s Republic to cow and silence outspoken critics, dissidents, professionals in all fields, citizen journalists, writers of conscience, outraged individuals, or indeed a plethora of others who resist the Communist Party’s imposed, and heavily policed, status quo.

In discussing this topic, and the problems that China’s rulers create not only for the people over whom they rule, but for themselves as well, Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, an outspoken professor of law, frequently employs the ancient term 鉗口 qián kǒu, also 箝口, to close the mouth tightly, or to have someone silenced. It is a shorthand for 鉗口結舌 (also written 箝口結舌 or 緘口結舌), that is ‘to seal the mouth and tie the tongue in a knot’. Through the ages, while some wise souls repeatedly cautioned against it, others have been enthusiastic advocates in favour of shutting people up. The medical-political-social crisis of the coronavirus in 2020 has focussed people’s attention on a subject that has obsessed the Communists since they first purged outspoken writers in their own ranks in 1943.

During the 2019-2020 coronavirus crisis, people from many parts of China and from various walks of life expressed their outrage at having their ‘mouths sealed shut’ 封口 fēng kǒu, or for being ‘forbidden to speak out’ 禁言 jìn yán. The latter term — a neologism created at the turn of the millennium to express protest against constant government interdictions of free speech online — enjoyed particular currency after the death of Li Wenliang 李文亮, one of the eight Wuhan-based ‘whistle-blower doctors’ who had first expressed concern about a mysterious new flu-like illness in late December 2019.

***

For students of New Sinology, it is of some interest that the Tang-dynasty writer Du Mu’s poem, with which we began this essay, links Xu Zhangrun, China’s most outspoken public intellectual, with Xi Jinping and the rogue CCTV presenter and independent ‘citizen journalist’ Li Zehua 李澤華. Here the issues revolve around the bugbears of modern Chinese citizenship: the right to know 知情權 and the right to speak out 發言權. Before following those connection, however, we first offer some observations by Sebastian Veg on the role of Chen Qiushi 陳秋實, a lawyer and controversial independent journalist, who disappeared while reporting from the epicentre of the coronavirus outbreak.

Dr Veg is a scholar whose work on grassroots Chinese intellectuals is essential reading for those interested in understanding the history and significance of unofficial media and independent thinkers and writers in China today. In Minjian: The Rise of China’s Grassroots Intellectuals (New York: Columbia University Press, 2019) he focusses in particular on ‘intellectual spaces and networks: unofficial journals, commercial newspapers, bookstores, artist village, social media … to document a social phenomenon, which leads to a redefinition of who can be considered an intellectual in today’s China.’ Veg thus introduces a noteworthy range of thinkers, journalists and activists — ‘a new group of intellectuals sharing some combination of freelance position, unofficial status, and grassroots connections.’ In so doing, he offers a historical context to understand the evolving situation in the People’s Republic today not only by tracing free speech in the context of the (fitful) opening and closing of the media landscape and professional possibilities, but also by discussing the unsteady maturation and constant impoverishment of those who would speak out in a society that is repeatedly hobbled by Party paternalism.

We are grateful to Dr Veg for responding so generously to a request to offer his preliminary observations on Chen Qiushi and his place in contemporary Chinese media culture.

***

— Li Chengpeng 李承鵬, ‘Speaking Out:

Record of a Speech at Peking University’

說話: 北大演講錄, trans. Sebastian Veg in

Minjian (New York, 2019), p.232

***

Chen Qiushi 陳秋實 —

Rogue Reporting from the

Epicentre of a Crisis

Sebastian Veg

As the extent of the Wuhan virus outbreak became clear, a series of well-rehearsed phenomena could be observed. The public, losing trust in messages issued by the state, turned to sources of information that can be described as minjian 民間, that is, unofficial, self-organised, originating within society rather than being generated by state institutions. Two well-known forms of minjian information are: independent journalists or ‘self-media’ 自媒體; and, those possessed of professional expertise outside officialdom, an example being the retired doctor and virologist Zhong Nanshan 鐘南山, whose intervention on 19 January seems to have been the decisive factor for the breakthrough in the state’s recognition of a public health crisis. Some other professionals, in particular doctors, also spoke out to the media on the basis of their expertise, and in so doing contradicted the state narrative. As has been widely reported, eight of these ‘whistle-blowers’ were disciplined in January 2020 for having done so in late December 2019.

Hong Kong, with its expertise in infectious diseases and a free press, has also remained an important source of information, though notably less so than during SARS.

Chen Qiushi 陳秋實, a lawyer who already enjoyed something a reputation as a self-proclaimed independent investigator, in particular as a result of a fledgling attempt to cover the 2019 Hong Kong protests for Mainland viewers, travelled to Wuhan on 23 January to report on the unfolding crisis. Chen situated himself in the new tradition of the ‘citizen journalists’ that appeared and gained popular influence throughout the 2000s (the Communist Party may well now prefer to refer to that decade as the ‘Noughties’). However there are some differences between Chen’s public persona and activities and the earlier wave of non-official journalists.

In the 2000s, citizen journalists appeared within the larger context of investigative journalism that was nurtured mainly by the Southern Media Group and a few other quasi-independent news outlets. Ten years on, both that particular ecosystem, as well as the original citizen journalists themselves, have all but disappeared. Southern Weekend 南方周末 was ‘harmonised’ into oblivion by the authorities at the time of the Lunar New Year festivities of 2013. Caijing 財經, the media group that originally broke the SARS story, had fallen victim to a crackdown because of its coverage of the 2009 protests in Urumqi, although its editor, Hu Shuli 胡舒立 was able to salvage part of her team and regroup as Caixin Media. Caixin is the last holdover from that era, presumably protected by powerful financial interests within the party-state system. Once again it has proved to be instrumental in reporting on developments in Wuhan during the 2020 coronavirus crisis, including its interview with Li Wenliang 李文亮, the most famous (now deceased) member of the whistleblower doctors, and for investigating claims that many deaths that occurred early had been mis-classified as ‘ordinary pneumonia’ and therefore not included in official statistics. It also recently published a wide-ranging interview with an expert on the crisis. [See, for example, ‘對話高級別專家組成員袁國勇:我在武漢看到了什麼’,《財新網》2020年3月8日.]

A major difference between the 2000s and the early 2010s is, as we have indicated, that the underpinnings of the old media ecosystem that once flourished, no matter how fitfully, have been severely eroded. As Chen Qiushi observed in a video posted on 30 January, there may only be around 200 investigative journalists left in China and none of them had managed to get to Wuhan. Another example of such self-organised reporting includes Fang Bin 方斌 and his ‘People’s Self-Salvation’ 全民自救 initiative, ‘a campaign to know the truth, a campaign for openness and transparency.’ [See: ‘公民記者方斌發聲懷念李文亮醫生,呼籲「全民自救」和「反抗暴政」後被失蹤’, VOA, 2020年3月5日.]

Chen Qiushi’s video reports which were followed by 430,000 YouTube subscribers — he also had 246,000 Twitter followers — were strikingly different from anything that could have appeared in the 2000s, when citizen journalists prided themselves first and foremost on reflecting through their work superior professional ethics to those practiced by state media. Could anyone imagine Chang Ping 長平 or Hu Shuli appearing seated on a bed in a hotel room wearing a singlet and with unkempt hair and addressing the camera with details of their upset stomach, as Chen Qiushi did in his video of 30 January? Setting out to Wuhan on the eve of the 2020 Lunar New Year, Chen was apparently unprepared for the arduous undertaking upon which he had embarked. A week later, racked by a cough and diarrhoea, suddenly it seems to dawn on him that he may not have taken adequate precautions to ensure his own health. Was it really such a good idea to join a queue in a hospital with people waiting to be tested because they have presented with suspicious symptoms wearing only a face mask? By so doing was it responsible to waste possibly a precious test kit, supplies of which were already under great stress? Indeed, was it responsible journalistic practice — or, for that matter, morally justifiable — to interview on camera a woman who was holding a recently deceased relative in her arms? (See Chen’s 30 January video report at minute 23:00.)

Chen reported that he had witnessed distressing scenes in areas of the hospitals that he had been allowed to enter. Perhaps things were far worse in places to which he had not been privy? Perhaps the virus is far more dangerous than he had originally thought? How much of what he was reporting could readily be verified? At this point, Chen attempted to make contact with one of the only Hong Kong journalists in the city, only to learn that she had been forbidden by her employer to leave her hotel room due to the inherent dangers of the situation. Interestingly, Chen himself addressed the questions raised by his reporting in his next video, published two days later on 1 February. In it he apologises for being ‘overly emotional’ and ‘unprofessional’, adding that journalists should at all times remain ‘objective, rational and balanced’ 客觀、理性、公正.

During his reporting venture in Wuhan, which was curtailed by his sudden disappearance on 6 February, Chen undoubtedly uncovered significant information, such as the fact that local taxi drivers had been discussing the appearance of a ‘SARS-like illness’ in December, or that the local official Chinese Red Cross was so corrupt that people were sending their donations directly to hospitals, overwhelming mail rooms as a result. Without discounting Chen’s work, it must be noted, however, that there is little doubt that its limitations reflect the fact that the present level of professional ethics to which citizen journalists hold themselves has been severely affected by the relentless media crackdown of recent years. New activists are suppressed nearly as soon as they appear, therefore there is scant opportunity or time for them to appreciate, share and transmit knowledge about the standards established by their predecessors. Still, it is remarkable that, given these straightened circumstances, someone like Chen Qiushi could appear at all. He provided important updates on the situation in Wuhan until he, like others who attempted to emulate him, were silenced.

Choked with Silent Fury

Du Mu’s famous poetic line ‘The folk of All Under Heaven/ Cannot voice their rage’ 天下之人, 不敢言而敢怒 was reformulated as 敢怒而不敢言 gǎn nù ér bù gǎn yán, that is, ‘to choke with silent fury’. These words have given voice to popular outrage protesting autocratic behaviour, corruption and misrule for centuries. It is an expression that has resonated throughout the history of the People’s Republic of China. While it all too common for people to ‘keep quiet’ 失聲 repression, there are aways those who ‘dare to speak out’ 敢言 gǎn yán.

***

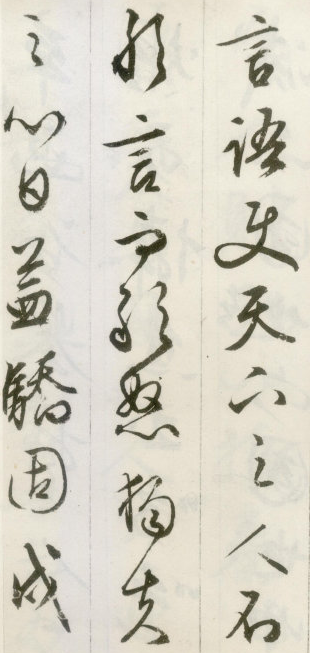

Grows ever more arrogant and proud.’ Lines from Du Mu’s rhapsody in the hand of Wen Zhengming 文徵明 of the Ming dynasty, translated by John Minford

***

Lamenting

Readers of China Heritage would have first encountered a reference to Du Mu’s ‘The Great Ch’in Palace, a Rhapsody‘ in China’s Red Empire — To Be or Not To Be (China Heritage, 16 January 2019), an essay by Xu Zhangrun, the outspoken professor of law formally ‘de-mobbed’ by his employer Tsinghua University in March 2019. Writing in December 2018, Xu warned that, under Xi Jinping, the head of China’s party-state-army, the People’s Republic was on the road to becoming a new empire, one whose global ambitions would invariably be matched by imperial folly. As part of his warning — one of many that he had issued since early 2016 — Xu pointed out that the country had only recently recovered from another era of vaunting, but failed, imperial-scale ambition. Quoting an expression from Du Mu’s poem, Xu reminded readers that:

During those decades [of Maoist rule, from 1949 to 1979] not only were the butchers themselves sacrificed on the altar of ideology, mourned in turn after others had been mourned for, but more importantly the countless multitudes of China were caught up in the maelstrom. It feels like only yesterday that bloody violence swept the land. Having barely survived that calamity you can just imagine how people must be reacting to the renewed drumbeat of war.

須知,長達三十多年里,國朝奉行殘酷鬥爭哲學,曾經連年「運動」,不僅劊子手們自己也先後走上祭壇,哀復後哀,而且,更要命的是使億萬國民輾轉溝壑。血雨腥風不過就是昨日的事,好不容易熬過這一劫,又聽鼙鼓,你想天下蒼生心裡該是何種滋味。

The words ‘mourned in turn after others had been mourned for’ 哀復後哀 āi fù hòu āi were a pointed reference to the sombre concluding lines of Du Mu’s ‘The Great Ch’in Palace’, translated by John Minford for China Heritage and the theme of the present essay:

The Rulers of Ch’in had not a moment

To lament their fate,

Those who came after

Lamented it.

When those who come after

Lament but do not learn,

Then they too will merely provide

Fresh cause for lamentation

From those who come after them.

秦人不暇自哀

而後人哀之

後人哀之

而不鑒之

亦使後人

而復哀後人也。

***

Less than a year later, Xu Zhangrun’s nemesis would himself refer to Du Mu’s poem, and quote it at length.

On 2 October, only a day after he had officiated over a grand parade celebrating the seventieth anniversary of the People’s Republic at Tiananmen Square in Beijing, China’s leader leader Xi Jinping published his latest thoughts on rulership and governance in the Communist Party’s main theory journal. Among the quotations from speeches marshaled in an article on the topic of rulership was one from remarks Xi had made on 31 October 2017 when paying a formal visit with the other members of China’s ruling Standing Committee of the Party’s Politburo to the site of the first congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai.

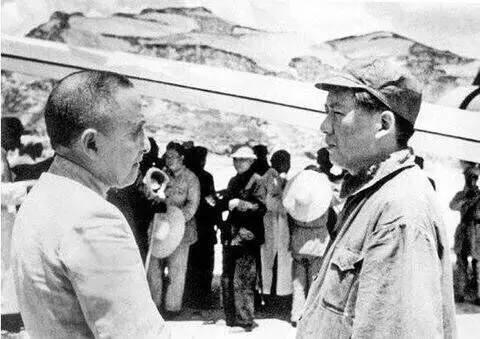

On that occasion, Xi referred to a famous claim that Mao Zedong had made in July 1945 when a delegation of independent intellectual leaders visited the Communist wartime base in Yan’an, northwest China. The group had been invited as part of the Party’s efforts to establish their legitimacy with the nation’s intelligentsia and to form a united front with patriots of various backgrounds in preparation for the ultimate conflict with the ruling Nationalist Party under Chiang Kai-shek for control over China.

On the 4th of July, Mao asked one of his visitors — the educator and progressive political activist Huang Yanpei (黃炎培, 1878-1965) — what he thought about what he had seen during his visit to the Yan’an base. Huang praised the collective, hard-working spirit evident among the Communists and their supporters, but he expressed doubts about whether such wartime frugality and solidarity could last in peacetime. He predicted that if the Communists ended up ruling China, their revolutionary ardour would eventually wane. He wondered out loud whether the corrupt and autocratic political habits of China’s past would haunt the future.

Huang saw no way out of the ‘vicious cycle’ of dynastic rise and collapse.

***

***

Mao was unequivocal in his response: ‘We have found a new path; we can break free of the cycle’, he declared:

The path is called democracy. As long as the people have oversight of the government then government will not slacken in its efforts. When everyone takes responsibility there will be no danger that things will return to how they were even if the leader has gone.

The exchange between Mao and Huang Yanpei was recalled in official propaganda in 1990 and it has been a constant feature of Communist claims that theirs is really a democracy ever since. The reprinting of Xi Jinping’s comments on the Qin empire on the seventieth anniversary of Communist rule had a particular point, for it referred to the conversation between Mao and Huang in 1946, one that has absorbed Chinese thinkers both past and present, that is the ‘endless return’ of Chinese history — the rise and inevitable fall of dynasties. It is known as the ‘theory of dynastic cycles’ 週期論.

In the article published on 2 October 2019, Xi Jinping was quoted as having said:

I often talk about ‘cyclical history’, it’s a perennial topic in Chinese history. Having unified All Under Heaven, Qin Shihuang gave license to all kinds of self-indulgence and corruption as well as allowing outlandish extravagance at the same time as stealing from the people, imposing corvée labour. [The peasant leaders] Chen Sheng and Wu Guang rose up in rebellion and attracted universal support. Following the storming of Qin lands, Xiang Yu [the rebellious leader from the former State of Chu] burnt the Epang Palace to the ground. This loss would later be written about with thoughtful regret [by Du Mu]:

我經常講到歷史週期率問題,這的確是我國歷史上封建王朝擺脫不了的宿命。秦始皇統一天下後,窮奢極欲、揮霍無度,搜刮民財、徵用民力,陳勝、吳廣揭竿而起,四方響應,函谷關被攻破,項羽放了一把火,富麗堂皇的阿房宮變成一片焦土。後人感嘆說:

The Six Kingdoms

Themselves caused their own downfall,

Not the Might of Ch’in;

Ch’in itself wiped out its own line,

Not All Under Heaven.

Alas!

If the Six Kingdoms had but loved their own folk,

They would never have fallen to the Might of Ch’in.

If Ch’in in its turn had but loved its own subjects,

Taken from the Six Kingdoms,

Ch’in could have prolonged its rule,

And no one could have destroyed it!

The Rulers of Ch’in had not a moment

To lament their fate,

Those who came after

Lamented it.

When those who come after

Lament but do not learn,

Then they too will merely provide

Fresh cause for lamentation

From those who come after them.

滅六國者,

六國也,

非秦也。

族秦者,

秦也,

非天下也。

嗟乎!

使六國各愛其人,

則足以拒秦;

使秦復愛六國之人,

則遞三世可至萬世而為君,

誰得而族滅也?

秦人不暇自哀,

而後人哀之;

後人哀之而不鑒之,

亦使後人而復哀後人也。

Xi had gone on to observe that:

Our Party and our nation are, by their very nature, fundamentally different from those feudal-era dynasties and peasant rebellions. One cannot make simplistic comparisons, but history can provide us with insights into the principles of [political] rise and fall [that is, longevity and failures].

我們黨和國家的性質宗旨同封建王朝、農民起義軍有著本質區別,不可簡單類比,但以史為鑒可以知興替。功成名就時做到居安思危、保持創業初期那種勵精圖治的精神狀態不容易,執掌政權後做到節儉內斂、敬終如始不容易,承平時期嚴以治吏、防腐戒奢不容易,重大變革關頭順乎潮流、順應民心不容易。

There are eighty-nine million Party members and over four and a-half million local Party cells. The only way we can lose is if we defeat ourselves. During the raid on Prospect Garden described in Chapter Seventy-four of The Dream of the Red Chamber, Jia Tanchun observes that:

‘A great household like ours is not destroyed in a day. “The beast with a thousand legs is a long time dying.” In order for the destruction to be complete, it has to begin from within.’ [trans. David Hawkes] …

我們黨有8900多萬名黨員、450多萬個基層黨組織,我看能打敗我們的只有我們自己,沒有第二人。《紅樓夢》第七十四回里,賈探春在抄檢大觀園時說過一句話:可知這樣大族人家,若從外頭殺來,一時是殺不死的,這是古人曾說的「百足之蟲,至死不僵」。…

That’s what we mean when we talk about the need for constant revolution within ourselves.

這就是為什麼我們黨要不斷進行自我革命的根本意義所在。

To appreciate this better, we must recall that when the revolution succeeded [in 1949], the Party issued three demands to all leading cadres: in the first place, they must never become divorced from the Masses of People, even for an instant, and always remain open to the surveillance of the People; secondly, to persevere with the struggle without cease never giving in to hubris and self-assured arrogance; and, thirdly, maintain one’s political purity and forever guard against the enticements of all kinds of corruption. These are the three reasons that we are still here and if we want to continue ruling we will adhere to these three points.

為瞭解決這個問題,中國革命勝利時,我們黨向領導幹部提出3點要求,一是時刻不能脫離人民群眾、自覺接受人民監督,二是永遠不能驕傲自滿、始終艱苦奮鬥,三是時刻防範糖衣炮彈、永葆政治本色。我們黨之所以能夠走到今天離不開這3點,我們黨要繼續長期執政,也離不開這3點。

China Heritage, January 2019

During the coronavirus crisis, outspoken critics of Xi Jinping like Xu Zhangrun, Xu Zhiyong, Guo Yuhua, Ren Zhiqiang, and even the more moderate Zhao Shilin, have all pointedly commented on Xi’s own failure to adhere to the principles that he has so frequently, and pompously, advocated.

Epang Palace Revisited — Searching for Li Zehua

On 28 December 2016, Li Zehua (李澤華, aka Kcriss Li, 1995-), a broadcast journalism student studying in Beijing, was awarded first prize at the annual Qi Yue Recitation Arts Festival for his rendition of Du Mu’s ‘The Great Ch’in Palace’.

Li Zehua’s Recitation of ‘The Great Ch’in Palace’

After enjoying a short-lived stint as an onscreen presenter for China Central TV, Li took up ‘self-media’ production and, in February 2020, travelled to Wuhan to report on the coronavirus crisis in the city as a citizen journalist.

Opening the Door

On Wednesday this week [26 February 2020], Li Zehua (李泽华), a journalist who recently resigned from his job as a news anchor at China’s state-run China Central Television to report as a citizen reporter on the front lines of the epidemic in Wuhan, was apparently detained by officers from state security. His whereabouts are currently unknown.

Li, who had managed to livestream his dispatches, and who also reported continued harassment from local police and security guards, arrived at Wuhan’s Baibuting Community, an area hit particularly hard by the epidemic, on February 16. He livestreamed a story on February 18 from a crematorium in the city about how porters were being hired at high wages in order to transport corpses. On February 25, he did a report in which he interviewed migrant workers who were forced to set up camp in the underground parking garage at Wuchang Railway Station.

Li’s citizen journalism in Wuhan followed in the footsteps of two other journalists, Fang Bin and Chen Qiushi, both of whom are now missing.

As state security officers caught up with him and prepared to detain him Wednesday, Li Zehua recorded a final message speaking to the men outside his door.

In this message, he talks about his belief in the importance of speaking up and the inspiration he took from Chai Jing (柴静), the celebrity CCTV anchor whose documentary “Under the Dome,” about serious air pollution in China, drew more than 300 million views online before being deleted by authorities.

Our translation of Li Zehua’s message follows.

— China Media Project

***

Li Zehua’s Message

Translated by China Media Project

OK, I’m getting ready to open the door. Can I say a few things?

First of all, I admire those of you who have hunted me down. I admire the diverse methods you employed under the light of day to track down my position so accurately. The way too that you managed to pressure my friends XX to come over.

Secondly, from the time I first arrived in Wuhan everything I have done has been in accord with the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China and with its laws. I had full protective gear for all of the places I visited that were designated as danger areas – a protective jacket, goggles, disposable gloves, disinfectant. I had plenty of all of these things, a full supply of materials. This 3M mask, this was bought for me by a friend who supported me. So right now I’m physically fine. My body is strong and healthy. If you say I have a temperature, this can only be because it’s too stuffy inside all of this gear.

Of course, the third thing is that I realize at this point that it’s highly unlikely I won’t be taken away and won’t be quarantined. I just want to make it known, though, that I have a clear conscience toward myself, a clear conscience toward my parents, a clear conscience toward my family, and also a clear conscience toward the Communication University of China from which I graduated, and toward the journalism field in which I did my studies. I also have a clear conscience toward my country, and I have done nothing to harm it. I, Li Zehua, 25 years of age, had hoped I could, like Chai Jing [the former CCTV journalist who made the documentary “Under the Dome”], work on the front lines, that I could make a film like the one she did in the environment of 2004 about the fight against SARS in Beijing. Or like “Under the Dome” in 2016, the one that was completely blocked online.

I think if you big guys outside the door went to middle school, which of course you did, and if your memories are good, you’ll definitely remember the essay we all had to read by Lu Xun, the one called, “Has China Lost It’s Confidence?” There’s a line I’ve always found inspiring where Lu Xun says: “In this China of ours there have always been those who speak for the people, who fight tenaciously, who abandon their bodies in search of the truth . . . . In these people we discover China’s spine.”

I’m not willing to disguise my voice, nor am I willing to shut my eyes and close my ears. That doesn’t mean that I can’t live a happy and comfortable life with a wife and kids. Of course I can do that. But why did I resign from CCTV? The reason is because – I hope more young people, more people like me, can stand up!

But this isn’t for the sake of uprising or anything like that, that’s not what I mean. It’s not as though we oppose the Party simply by saying a few words. I know that our idealism was already annihilated in spring and summer that year [1989], and sitting quietly [in protest] no longer accomplishes anything.

Today’s youth, who go onto Bilibili, Kuaishou and Douyin and swipe their way through social media, probably have no idea at all what happened in our past. They think the history they have now is the one they deserve.

I think everyone is like Truman, and when they discover that strange radio frequency, and when they find the exit door, they walk out and feel they can never go back.

The last thing I’ll say is, I’m sorry.

I’ll just say, I really understand you guys outside the door. I understand the mission you’ve been given. But I also sympathize with you, because when you support, without conditions and without reason, such a cruel order, the day will come when the same cruel order falls on your own heads.

OK, that’s it. I’m ready to open the door.

— China Media Project

28 February 2020

***