— Geremie R. Barmé

January 2016

On Heritage 遺

Geremie R. Barmé

For every plain there is a slope, 無平不陂,

For every going there is a return. 無往不復。

— Hexagram XI, I Ching 周易 泰掛繫辭

The Gifts of Yí 遺

China Heritage takes the word yí and the hand-written grass-script character 遺 as its theme and motif.

Yí 遺 embraces various meanings that relate to that which is voluntarily left behind, is extant or remains in the world either by design or circumstance. It also indicates those practises and dispositions of the spirit and mind that tether the past to the present.

Yí 遺 is used in many compound terms and expressions to indicate loss, the discarded, the overlooked and missed out, as well as the forgotten and remnant. Yí 遺 also denotes the physical remains and material works left by the departed: the formal term for a corpse is yítǐ 遺體, that is ‘corporeal remains’ or, in the literary language, yíhài 遺骸. The visage of the deceased, or corpse 遺屍, is called an yíróng 遺容; although over the past century votary images of ancestors 遺像 have been replaced by photographs of the dead 遺照.

The disposition of an estate, personal possessions and properties in a will 遺囑 or 遺書, or the gift to the living of such intangible inheritances as respect for honoured practices and mores 遺風, compliance with the last wishes of the dead 遺志/遺願, as well as the recollection of edifying instructions 遺訓 and teachings 遺教/遺言 all contain the word yí 遺, as does the description of an idyllic past when ‘no one would pick up things lost by others on the roadside’ 路不拾遺.

Handwritten manuscripts 遺稿 and poems 遺詩, essays 遺文 or collectanea 遺集 by the departed also feature yí 遺, and such works might well be included as an addendum 補遺 to a book, just as some collections could bring together recondite or little known stories of the past or people 遺聞軼(逸)事. It is in such works, and because of the fear of obvilion, that the living strive not to be forgotten 遺忘. Yí 遺 is also the key element in the terms for bequests 遺產, physical objects and personal effects left behind 遺物, unfulfilled or, paradoxically, exemplary tasks 遺事, unresolved cases 遺案, legal or otherwise, historical sites and their ruins 遺址, as well as archaeological remains 遺跡: collectively they comprise a physical heritage 遺存.

Illnesses or social ructions can produce any number of after-effects 後遺症, just as history leaves in its wake problems for the present 歷史遺留下來的問題. So too the DNA of the living transmits a genetic imprint 遺傳 to future generations. Among them are the descendants 遺族 of once mighty figures to whom are bequeathed unfulfilled dreams 遺夢, sentiments of regret 遺憾 or the sense of loss 遺失 and sorrow 遺恨. A dead man may leave behind a widow 遺孀 and, in some cases, even an unborn child 遺腹子. In an obscure usage, people may waste away 遺矢, or their names be omitted 遺漏 from the record. While rare individuals are celebrated for leaving to history a ‘fragrant name’ 芳名, the odium of the notorious long outlives them 遺臭千秋.

The word yí 遺 also relates to the giving of gifts and bestowal, in which case the character 遺 is read wèi. In that sense, it can also mean ‘to bid farewell’. Generally, however, it connotes that which remains, either in positive or negative terms.

Another World 遺世

Yí 遺 is also famously used in the twentieth century to deride the ‘remnants’ or anachronistic loyalists of China’s last dynasty, the Qing (1644-1912), men and women who were scorned for living beyond their time 遺民. Others, 順民, would accommodate themselves to a cavalcade of regimes. The word yí 遺 features in an expression that sums up modern contempt for those who remained steadfast in their devotion not only to the abdicated monarch and the former imperial Manchu ruling house, the Aisin Gioro 愛新覺羅, but even to the literary achievements, cultural standards, civilised behaviours and personal integrity espoused by scholars trained in the tradition. These people were dismissed, most famously by the acerbic writer Lu Xun 魯迅, as being ‘musty relics of a bygone age both young and old’ 遺老遺少.

The widespread odium attached to these ‘remnants’ has persisted since the abdication of the last emperor in 1912. For a time early last century there was good reason to be wary of such figures and to fear that the deadening hand of the past would strangle hope for the future. But, along with the heady iconoclasm of China’s revolutionary era (1912-1992), many positive mores of the previous ages, alternative traditions to state Confucianism and authoritarian thinking were also attacked. While much of the physical legacy of the past, historical sites and monuments, and ineffable practices and language have been swept aside by successive waves of zeal, the imperial mindset of dynastic China survives to this day in various guises.

Scholars of a certain generation, be they in China or elsewhere, are carelessly derided by the regnant academocrats and managerial nomenklatura for harbouring a nostalgia for the practices of yesteryear, for the pre-vocational university and educational ideas which, although far from ideal, put a premium on broad-based scholarship, reading and non-mercantile education.

China Heritage is a refuge for just such 遺老遺少: fogeys, old and young alike.

In recent times, as the perennial discussion of China’s unique history, civilisation, political disposition and place in the world is promoted as part of the Official China Story 中國的故事,[1] another hoary expression has regained currency. Some claim that because of its unique approach to politics and culture China ‘exists apart from the world’ 遺世獨立; it flourishes in a realm of its own, partaking of the global order yet all the while remaining above it. The expression originally meant ‘to cast aside worldly cares’ or ‘to leave behind the mundane world’ 遺世.

In his celebrated ‘Rhapsody on the Red Cliffs’ 赤壁賦 the eleventh-century Song-dynasty scholar-official Su Dongpo 蘇東坡 describes an autumn evening spent boating and drinking with friends. ‘We floated high on the water as if airborne,’ he wrote, ‘leaving the world behind transformed into heavenly immortals’ 飄飄乎,如遺世獨立,羽化兒登仙. The four-character expression also features in an essay by China’s great twentieth-century ‘artistic exile’, Feng Zikai 豐子愷: ‘Although I was physically sitting in a train,’ he wrote in 1935, ‘my spirit was free of worldly thoughts and remained as though sequestered in my study at home’ 那時我在形式上乘火車,而在精神上彷彿遺世獨立,依舊籠閉在自己的書齋中. (見豐子愷《車廂社會》).[2] Throughout the ages many have chosen to abandon the secular world and renounce its blandishments 遁世遺榮; and, for those who identify with alternative Chinese traditions that question or disavow the ‘dusty world’ 塵世, the expression yíshì 遺世 resonates still.

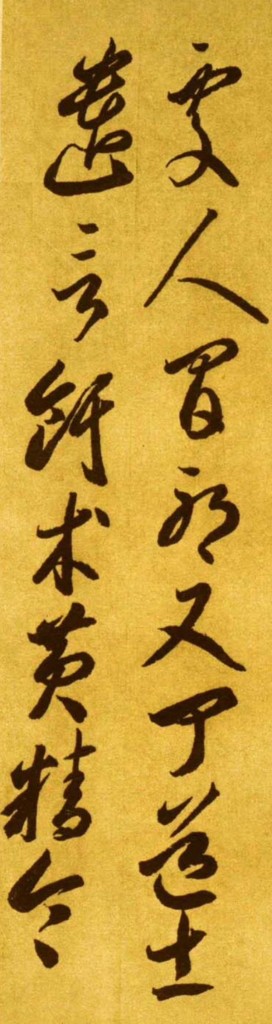

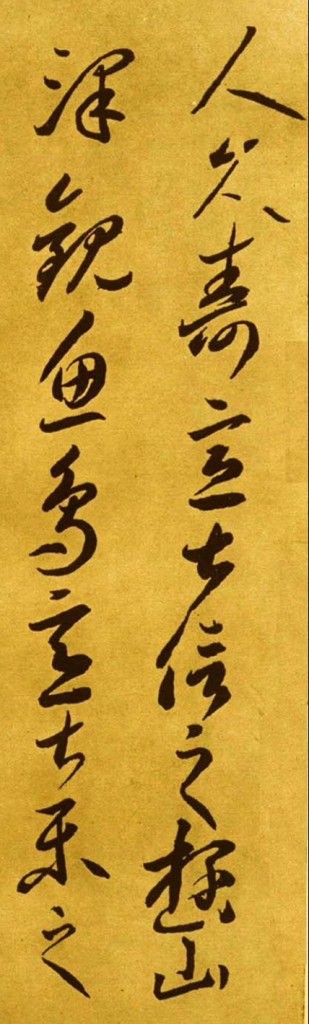

Native Woods and Rich Pasture 志在豐草

The character yí 遺 used here as our leitmotif is taken from the calligraphy 遺墨 of the Tang-dynasty artist Li Huailin 李懷琳. It occurs in Li’s grass-script 草書 version of a ‘Letter to Shan Tao’ 與山巨源絕交書, a famous epistle by Xi Kang 嵇康 (also pronounced Ji Kang), one of the celebrated Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove 竹林七賢, in which Xi ends his friendship with another member of the group.

Etienne Balazs remarks that:

In this letter, written shortly before his death, Xi Kang broke off relations with his former friend Shan Tao, who had not kept his vow of uncompromising integrity, and who, after accepting a high post, had even dared to suggest that Xi Kang should become his assistant. Xi Kang, full of violent indignation, threw the offer back in his face, saying abruptly that his aspirations were not of this world, and explaining with such eloquence what Flaubert somewhere in his letters has expressed in the lapidary formula: Les honneurs déshonorent, le titre dégrade, la fonction abrutit.[3]

In his ‘Letter to Shan Tao’, Xi Kang (223-262CE) says that the ‘wayward’ ideas of Taoist sages had long influenced his predisposition to reject worldly office:

… My taste for independence was aggravated by my reading of Zhuangzi and Laozi; as a result any desire for fame or success grew daily weaker, and my commitment to freedom increasingly firmer. In this I am like the wild deer, which captured young and reared in captivity will be docile and obedient. But if it be caught when full-grown, it will stare wildly and butt against its bonds, dashing into boiling water or fire to escape. You may dress it up with a golden bridle and feed it delicacies, and it will but long the more for its native woods and yearn for rich pasture. 又讀莊老,重增其放。故使榮進之心日穨,任實之情轉篤。此由禽鹿少見馴育,則服從教制,長而見羈,則狂顧頓纓,赴蹈湯火,雖飾以金鑣,饗以嘉肴,逾思長林,而志在豐草也。[4]

Like Xi Kang eighteen hundred years ago, our taste for independence was also aggravated early on by reading Laozi and Zhuangzi, among others; since then, the allure of golden bridles and delicacies has been but slight. We believe that through China Heritage and The Wairarapa Academy for New Sinology, and after long years spent in tertiary bonds, rather than seek release in boiling water or fire, it is time to return to native woods and rich pasture.

The Unbearable and The Unconscionable 必不堪者,甚不可者

Over the last century China’s power-holders have been tireless in their efforts to order life according to mutating political priorities and by enumerating and imposing social and ethical norms. The Chinese language is littered with the numbered slogans and exhortations imposed on the people, be they devised by the Nationalists or the Communists.

Xi Kang had a list of his own that he used to explain how unsuited he was to bureaucratic service. There were, he declared, ‘seven things I could never stand and two things which would never be condoned’ 有必不堪者七,甚不可者二:

- I am fond of lying late abed, and the herald at my door would not leave me in peace: this is the first thing I could not stand. 臥喜晚起,而當關呼之不置,一不堪也。

- I like to walk, singing, with my lute in my arms, or go fowling or fishing in the woods. But surrounded by subordinates, I would be unable to move freely—this is the second thing I could not stand. 抱琴行吟,弋釣草野,而吏卒守之,不得妄動,二不堪也。

- When I kneel for a while I become as though paralyzed and unable to move. Being infested with lice, I am always scratching. To have to bow and kowtow to my superiors while dressed up in formal clothes—this is the third thing I could not stand. 危坐一時,痺不得搖,性復多蝨把搔無已,而當裹以章服,揖拜上官,三不堪也。

- I have never been a facile calligrapher and do not like to write letters. Business matters would pile up on my table and fill my desk. To fail to answer would be bad manners and a violation of duty, but I would not long be able to force myself to do it. This is the fourth thing I could not stand. 素不便書,又不喜作書,而人間多事,堆案盈機,不相酬答,則犯教傷義,欲自勉強,則不能久,四不堪也。

- I do not like funerals and mourning, but these are things people consider important. Far from forgiving my offence, their resentment would reach the point where they would like to see me injured. Although in alarm I might make the effort, I still could not change my nature. If I were to bend my mind to the expectations of the crowd, it would be dissembling and dishonest, and even so I would not be sure to go unblamed—this is the fifth thing I could not stand. 不喜弔喪,而人道以此為重,己為未見恕者所怨,至欲見中傷者,雖瞿然自責,然性不可化,欲降心順俗,則詭故不情,亦終不能獲無咎無譽如此,五不堪也。

- I do not care for the crowd and yet I would have to serve together with such people. Or on occasions when guests fill the table and their clamor deafens the ears, their noise and dirt contaminating the place, before my very eyes they would indulge in their double-dealings. This is the sixth thing I could not stand. 不喜俗人,而當與之共事,或賓客盈坐,鳴聲聒耳,囂塵臭處,千變百伎,在人目前,六不堪也。

- My heart cannot bear trouble, and official life is full of it. One’s mind is bound with a thousand cares, one’s thoughts are involved with worldly affairs. This is the seventh thing I could not stand. 心不耐煩,而官事鞅掌,機務纏其心,世故繁其慮,七不堪也。

‘Further’, Xi Kang continued, there were two reasons why his views and behaviour would not be tolerated:

- I am always finding fault with Tang and Wu Wang, or running down the Duke of Zhou and Confucius. If I did not stop this in society, it is clear that the religion of the times would not put up with me. This is the first thing which would never be condoned. 又每非湯武而薄周孔,在人間不止,此事會顯世教所不容,此甚不可一也。

- I am quite ruthless in my hatred of evil, and speak out without hesitation, whenever I have the occasion. This is the second thing which would never be condoned. 剛腸疾惡,輕肆直言,遇事便發,此甚不可二也。

Fearful of the prestige Xi Kang enjoyed among the learned men of his time the ruler Sima Zhao 司馬昭 had him executed. He is said to have been only forty years old.

A Heritage of Teachings 遺言

Xi Kang declared he was influenced by ‘the heritage of teachings of the Taoist masters’ 又聞道士遺言 (or, in Hightower’s translation: ‘I have studied in the esoteric lore of the Taoist masters’) about prolonging life and nurturing the pleasure of ‘wandering among the hills and streams, observing fish and birds’ 遊山澤,觀鳥魚,心甚樂之. It is from this passage in his letter that we take the word yí 遺 in the hand of Li Huailin for China Heritage (see the image above).

It is just such a sentiment, an inspiration that draws on those other traditions of China, that guides our lifelong engagement with the vast Chinese heritage. It is what led to Wairarapa.

It is the leisure of mind afforded by such a disposition and what we call New Sinology that can best equip those who would delve into the Chinese world as they embark on their own venture.

Notes

[1] Geremie R. Barmé, Telling Chinese Stories, 1 May 2012.

[2] See Geremie R. Barmé, An Artistic Exile: a life of Feng Zikai (1898-1975), Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002.

[3] Quoted in John Minford and Joseph S.M. Lau, eds, Classical Chinese Literature: An Anthology of Translations, Volume 1: From Antiquity to the Tang Dynasty, New York: Columbia University Press, 2001, p.463.

[4] James Hightower in Minford and Lau, Anthology, pp.463-467. Quotations from Xi Kang are taken from Hightower’s translation. The Chinese text has been added.