Spectres & Souls

The following essay was drafted in the first days of September 2021 and revised on 9 September, the forty fifth anniversary of the death of Mao Zedong. On 9 September 1986, the date of the tenth anniversary of Mao’s demise, I found myself in Austin, Texas, and I celebrated the occasion in the boisterous company of loved ones by drinking a margarita for every year of the post-Mao era. I had only recently met Liu Xiaobo in Beijing and, when I told him about that bibulous libation, and its aftereffects, he laughed like a drain.

As part of ‘Over One Hundred Years’, a series of essays commemorating the centenary of the Chinese Communist Party in China Heritage Annual 2021: Spectres & Souls, we offer a prescient essay by Xiaobo. It is introduced by an extended discussion of the Counter Reform ‘interregnum’ of 1989-1992 and the background to the Xi Jinping Restoration that began in 2012.

As a Joint Fellow at both the Asia Society Policy Institute and the Center on US-China Relations, I very much appreciate the conversations and intellectual exchanges I have had with staff members and colleagues. My thanks also to Chris Buckley and Reader #1 for reading the draft of this essay and offering a number of suggestions. I am also grateful to Jeremy Goldkorn of SupChina (aka The China Project) for his interest in this topic and for his support.

For more on this topic, see Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, China Heritage Annual 2022.

***

Contents

This chapter of Spectres & Souls is divided into the following sections (click on a section title to scroll down):

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

20 September 2021

***

Related Material:

- ‘Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium’, China Heritage, 1 January 2022-

- ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, SupChina, 25 August 2021

- ‘Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold’, China Heritage, 13 July 2021

- ‘Xi Jinping’s China & Stalin’s Artificial Dialectic’, China Heritage, 10 June 2021

- ‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’, a five-part series on the first years of the Xi Jinping era, published in China Heritage, 8 August to 1 October 2018

- China Story Yearbook series — 2012: Red Rising, Red Eclipse; 2013: Civilising China; &, 2014: Shared Destiny

***

Prelude to

The Xi Jinping Restoration

Geremie R. Barmé

9 September 2021

2021: Not Such a ‘Profound Transformation’

Recent moves in Beijing to crack down on ‘immoral artists’ 劣跡藝人, the exploitation of youth ‘fandom’ 飯圈 and the corrupting influences of celebrity culture; concerns about young people holding themselves back from the daily grind by ‘lying flat’ 躺平 and going ‘inverted’ 内卷; the immodest extension of the Xi Jinping personality cult via the mandated use of ideology-heavy textbooks in schools nationwide from 1 September 2021; the Communist Party’s re-iteration of its legacy policy of ‘common prosperity’; continued dire warnings about runaway corruption; the taming of select billionaires in the hi-tech and real estate sectors; attacks on global capital and local corporations alike; talk about ‘profound transformations’ being afoot, along with panegyrics that extol the triumphant ‘return of red values, of heroism and of unyielding mettle’ 紅色回歸,英雄回歸,血性回歸; and, Xi Jinping’s stern warning to Party cadres both young and old that ever-new challenges and tireless struggle lie ahead, when taken as a whole bring to mind the sound and fury of the ‘Counter Reform’, a period of economic retrenchment and ideological adjustments that dated from June 1989 to February 1992.

A ‘Second Cultural Revolution’, but in Tiananmen Square

For over two and a half years, the future of the economic reforms that the Chinese Communist Party launched in 1978 and that had, in the space of a decade, begun to transform the economy and the lives of people throughout China were thrown into confusion as revivalist, quasi-Maoist ideas held sway once more after the People’s Liberation Army, militia forces and the police had quashed the mass popular protests that had spread from the heart of Beijing to over twenty other cities in April-June 1989.

For a time following the Beijing Massacre of 4 June 1989, there was even dark talk about the possibility that the Communist Party was preparing to launch a ‘Second Cultural Revolution.’ Many people, including the present writer, appreciated the irony of such nonsense since, from April 1989, the Party had made it abundantly clear that it believed that the protesters in Tiananmen Square were the ones agitating for a second Cultural Revolution. After all, from mid April, the rabble had demanded that Party leaders like Zhao Ziyang account for the endemic corruption that blighted everyone’s lives and that they permit what, to old-timers, seemed very much like the kind of ‘mass democracy’ 大民主 that took the form of ‘mass outspokenness’ 大鳴大放 and ‘mass discussions’ 大辯論 that had characterised the early months of the Cultural Revolution in 1966. Moreover, the pamphlets distributed by student protesters in 1989 were filled with scandalous rumors, revelations of state secrets and political programs: these too had all the hallmarks of the ‘big-character posters’ 大字報 of the past (Mao had supported the ‘Four Greats’ 四大 from the late 1950s; Deng had them banned in 1980). The student call for Party leaders to reveal details of their family assets along with their connections to big business and revelations about nepotism brought to mind the furious Red Guard attacks on cadres in 1966-1967 when, having raided Party offices, they discovered the extent of the secret privileges enjoyed by bureaucrats while the rest of the country had suffered years of poverty and deprivation. The rowdy demonstration at the Xinhua Men entrance to the Zhongnanhai Party Compound in April 1989 during which thousands of students demanded that Premier Li Peng show himself was reminiscent of the ‘Ferret Out Liu Shaoqi Battle Line’ 揪劉火線 set up by tens of thousands of Red Guards in the same spot during the summer of 1967 as part of their attempt to force the country’s president, as well as Deng Xiaoping, out of hiding. Then there were all those scenes of young people drawn to the full-throated rabble-rousers who were declaiming on campuses and in Tiananmen Square, as well as all of the boisterous parades and deafening slogan-shouting. It all reminded Deng Xiaoping and his comrades of the nightmarish explosion of Red Guards, and it felt too close for comfort.

When, on April 26th, the Party issued a response to the student-led unrest in the form of an authoritative People’s Daily editorial, it described the peaceful protests as nothing less than ‘turmoil’ 動亂. It was a pointed reference to the ‘ten years of turmoil’ 十年動亂 of the Cultural Revolution. Once again, the Party leaders were telling the country, young people were being manipulated to ‘engage in sabotage and plunge the nation into chaos’.

In the wake of 4 June, anxious to sidestep personal culpability for the policy debacles of 1988 and mass outrage over the repressive policies and rampant corruption that had fed the 1989 uprising, Deng Xiaoping was quick to accuse the United States and its surrogates of taking advantage of China’s new-found openness, its reform policies and the enfeebled leadership of Party General Secretary Zhao Ziyang to advance a decades-long strategy of ‘peaceful evolution’. According to Deng, in April-June 1989, a murky but coordinated plot had duly unfolded; local advocates of so-called democracy, media freedom and human rights were not only hellbent on undermining the Communist Party, they were in cahoots with the imperialist enemies of the past and determined to make China into an economic dependency of the West.

In tandem with the economic reforms launched in late 1978, Deng and his Mao-era colleagues had repeatedly attempted to re-impose harsh ideological controls on both the Party and the nation in a confounding stop-start fashion. The disconnect between the evolving economic agenda and the Party’s preferred forms of suffocating social management increased over time. Writing in late 1983 during the ‘Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign’ — the first ‘rectification movement’ launched by the Communists since Mao’s death in 1976 — I observed that:

‘To fling the doors of economics wide open and still expect to retain control of the people’s minds by using methods from the 1950s is the essential paradox of contemporary China, and the dilemma of her leaders. The Communist Party sees its main enemy in Western influences, heedless, for the moment, that China’s economic cure may well be the root-cause of her ideological disease.’

First, during the purge 1983-1984 purge, and again with the ouster of Party General Secretary Hu Yaobang in early 1987, key reform-minded thinkers, propagandists and bureaucrats had been sidelined, fatally undermining the internal debate about systemic change be it in the political, media or cultural realm. Zhao Ziyang had only reluctantly taken on the mantel of Party chief and he was undermined and stymied from the start. That weak starting position was further compromised by Deng Xiaoping’s own capricious behaviour in relation to crucial price-reform policies in 1988 making Zhao’s position all but untenable. The Counter Reformers were waiting in the wings to take advantage of whatever opportunity presented itself. The Tiananmen protests provided just such an opportunity.

From mid-1989, the Communist Party gerontocrats — Deng and his fellow Eight Elders 八老, along with the influential ideologues Hu Qiaomu 胡喬木, Deng Liqun 鄧力群 and Gao Di 高狄 — a group that, despite all the folderol about constitutional norms, collective leadership, and inner Party democracy, were the actual ruling elite of the party-state-army of China, had to contend yet again with the ‘primary contradiction’ of what, from 1978, had been hailed as ‘a new era’ 新时期, one between reformist economic imperatives and an habitual authoritarian mindset. Throughout this period, a questions of how far the reform agenda should go, and where it might lead, were topmost in the minds of China’s leaders. The clashes between individuals were ideological, personal, as well as familial. One of the central concerns of the Eight Elders was the question of who could be relied on to lead the country, and its economy, in such a way that vouchsafed their legacy, and the security (be it political or economic) of their families. As in the dynastic era, as well as during the long years of High Maoism (roughly 1957 to 1976), ‘succession’ was one of the most burning issues.

In 1987, the Party leadership summed up its ruling ethos in the slogan ‘One Center, Two Basic Points’ 一個中心,兩個基本點: the central task was to promote economic growth, but it could only be vouchsafed by managing two seemingly centrifugal forces, that is, unwavering political control (underpinning by ‘Four Cardinal Principles’) and ever-expanding economic reforms and open door policies. When, in the wake of the bloody repression of protesters in June 1989, the Party reaffirmed, and reimposed, unwavering centralised political control, the reform and open door policies had been thrown into disarray.

***

***

The Counter Reform of 1989-1992

June Fourth was followed by months of arrests, trials, investigations and denunciations. A top-down purge was launched of what, since 1986, had been dubbed ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ (Deng supposedly dropped the expression ‘Spiritual Pollution’ after learning that it was reminiscent of ‘degenerate art’ entartete Kunst, a term used by Adolf Hitler and the Nazis to condemn bourgeois and Bolshevik culture). In tandem with the attacks on ‘bourgeois liberalisation’, that is anything that challenged Party control, the authorities pursued the renewed promotion among primary and high-school students of the ‘Three Passions’ 三熱愛, that is: ‘passionate love for the Fatherland, for Socialism and for the Chinese Communist Party’, first introduced to China’s young people in 1981. (In September 2021, this threesome, originally promulgated in 1981, would be included in the core curriculum for all Chinese school students in the form of ‘Xi Jinping Thought’.)

The agenda of this ‘rectification’, or ‘recalibration’ 整頓, touched all spheres: first and foremost, the victors who had ousted Zhao Ziyang and left Deng becalmed, wanted to pursue the economic course correction that they had promoted since 1988, and various innocuous targets of the renewed anticorruption push had to be reined in. The dangers of corruption were, after all, now broadly associated with Zhao Ziyang, this included the new business ventures that were aligned with him and had supported his policies, as well as his international investor friends, including George Soros, whose Open Society foundation had played a not-insignificant role in the 1980s. However, this strategic crackdown left unscathed the families of most other Party leaders who had been carving out spheres of influence in the economy for nearly a decade. It also imposed renewed control over the media to prevent any unseemly revelations. It was in this context that the significance of the Bureau for Middle-aged and Young Cadres 中青幹部局 in the Party’s Central Personnel Department, established in 1981 at the insistence of Chen Yun 陳雲, came into focus. In what is rumoured to be his ‘last testament’ 遺訓, Chen was clear about the future: ‘Power should be handed down to our children; if not, after we’ve gone, our “ancestral graves” will be dug up’ 權力要移交給我們的孩子,不然我們以後會被挖祖墳的。If Chen was suggesting a way to address the ever-present succession problems of the Party, for decades it was less than successful.

Then there was the widespread canker of ‘cultural nihilism’ to tamp down. It was a portmanteau term that swept into its maw everything from independent journalism and unofficial history writing to free thinking and any political views that questioned or were critical of the Party. In particular, an emphasis was now placed on countering the wayward ideas of the young Tiananmen rebels who had been influenced by corrosive ‘Western values’. Widespread ignorance of China’s ‘particular national situation’ 基本国情, it was declared, had led the masses astray; in their folly, student demonstrators had mistakenly come to believe that society would benefit from such things as Western-style personal freedoms, independent workers’ unions, civil associations, an open media and electoral democracy. Post-4 June, the nation had to be re-educated, only then would people realise that the paternalistic policies of the Party offered China the only viable path to national strength and personal prosperity.

The leadership concluded that the failure to promote a ‘correct’ and uplifting interpretation of national and party history had contributed significantly to the anarchy of 1989; it was a matter of utmost urgency to confront the widespread dearth of patriotic fervor and the precipitous decline of the militant spirit of struggle among cadres. The political coherence of Party cells had been undermined by neglect and urgent action was required to reinvigorate their role in all aspects of life. Fearful of the disaffection of its members as a result of post-Zhao ideological confusion, the Party resorted to the lavish promotion of the ‘red tradition’, including the selfless Jiao Yulu 焦裕禄, a long-forgotten cadre-martyr, the red samaritan Lei Feng 雷锋 and the ‘Yan’an Spirit’ 延安精神. A new national history research institution was established along with a centre specialising in the promotion of the Yan’an Spirit, both of which have enjoyed renewed support under Xi Jinping.

Meanwhile, in the peripheral territories of the nation, the successful crushing of the 1987-1989 rebellion in Tibet provided an important lesson for the future and Hong Kong was identified as a base both for seditious activities and dangerous ideas. Furthermore, Taiwan was increasingly regarded as an existential threat: its mooted transition to democracy from the late 1980s, while promising to fulfill the original promise of the 1911 republican revolution, constituted a direct challenge to the Communist Party dogma that a united China could only prosper under its rule.

(Following the end of the ‘Counter Reform’ in early 1992, Deng Xiaoping started promoting a seemingly non-threatening ‘hide and bide’ strategy internationally. To skeptics, however, regardless of the rhetoric, it was patently obvious that as soon as the country’s ‘comprehensive national power‘ 綜合國力’ allowed, it would no longer be necessary either to bide one’s time or hide one’s ambitions. See, for example, Liu Xiaobo, ‘Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’.)

From late 1989, young urbanites, deflated following the merciless crushing of the carnival-like protest movement, were said to be afflicted by a new mood, one that was called a ‘gray sensibility’ 灰色情绪. It was a syndrome that combined hopelessness, uncertainty and ennui with irony, sarcasm and a large dose of fatalism. Desperate for entertainment and diversion, club-goers and ‘gray youth’ were finding solace in the music and celebrities of Hong Kong and Taiwan, many of whom had built a fanbase on the mainland. Here too lay danger, for the escapism of young people alerted the authorities to the need to staunch the corrupting influence of non-official culture and the inroads of offshore media conglomerates in China proper. In August 1989, a National Office of the Leading Group Overseeing the Rectification and Re-alignment of the Publishing Industry 全國清理整頓書報刊領導小組辦公室 was established not only to ban books and magazines guilty of propagating dangerous ideas, but also to investigate and outlaw all forms of ‘pornography’ and corrupting off-shore influences.

Already on high alert as it cleared out the publishing industry, banning numerous books, magazines and newspapers, while promoting other stalwart anti-reform print platforms like Mainstay 中流 and The Quest for Truth 真理的追求, the Party’s reinforced propaganda apparatus also turned its attention to popular culture. An official campaign was launched to ‘wipe out star-chasers’ 滅追星族, that is celebrity-besotted young people, and regulate pop-star culture. Appearances by commercial celebrities were duly limited. The authorities argued that, surely the spirits of the ‘gray youth’ would be lifted if they could only be encouraged to sing stirring pro-Party ‘red songs’ and patriotic hymns at the newly popular karaoke bars, instead of being allowed simply to parrot the effete and lovelorn tunes from Hong Kong and Taiwan. Rock ’n roll, punk and heavy metal music might have niche appeal, but stirring patriotism, realigned thinking and military bootcamp were the real cure for the debilitating youthful malaise that characterised China in years 1989-1992 .

For all of the stentorian talk issuing from on high about ‘rectification’ 整頓 from 1989, however, Party leaders were hesitant to embark on a new political purge and mass mobilisation campaign of the kind that had been common in Mao’s day. They knew that to do so could fatally undermine the hard-won achievements of the reforms, the success of which bolstered their rule (and fattened their purses), just as they were aware that the masses could no longer be whipped up into the kind of mindless political frenzy that would be required. So, even as the call went out to clean up the arts and academia, to denounce the ‘spiritual elites’ 精神精英 who had held sway in the lead up to 4 June, a new cultural and intellectual ‘flourishing’ 繁榮 was also being encouraged, but this time in the spirit of Mao Zedong’s 1942 ‘Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Art and Literature’.

In short, the Counter Reform years rather than being anti-reform represented an attempt by contending factions to shore up the core interests of the Party, further entrench the power of the gentry and corral the social forces and political aspirations unleashed during the previous decade.

In the long run, the mixed messages and clumsy efforts of officialdom during the 1989-1992 ‘interregnum’ helped usher in the ebullience of the Jiang Zemin era — Jiang having adroitly abandoned his previously ‘conservative’ stance on the economy and cannily curried favour with Deng et al as something of a ‘born-again reformist’ in the months leading up to the Fourteenth Party Congress, held in October 1992. (For details, see Tony Saich, ‘The Fourteenth Party Congress: A Programme for Authoritarian Rule’, The China Quarterly , No.132 (December 1992): 1136-1160; and my ‘The Graying of Chinese Culture’, 1992, a revised version of which was included in In the Red: contemporary Chinese culture, New York, 1999.)

***

***

A Volte-face in 1992 &

Again in 2012

By late 1991, the substantive reform was stalled and economic growth was in the doldrums. Rancorous debate over the direction and pace of change continued as the populism of the late 1980s found a new expression in nostalgia for Mao Zedong and an era that seemed simpler, more frugal and less corrupt. New forms of patriotic zealotry were developing and a broader critique of the open door policies within the Party leadership and among its thinkers was supported by neo-Marxists. Deng Xiaoping was all too aware of the fragile loyalty of the party gentry and nomenklatura, a group of a few hundred families that had enjoyed the spoils of the reforms for over a decade. He was also mindful of the role that hidebound economic policies had played in the recent collapse of the Soviet Union. Although the sclerotic policies of the Counter Reform were an inevitable short-term corrective to the Zhao debacle, and a sop to his more cautious colleagues like Chen Yun, Li Xiannian, Wang Zhen et al, they threatened to undermine the Herculean achievements of previous years, not to mention the long-term viability of Party rule.

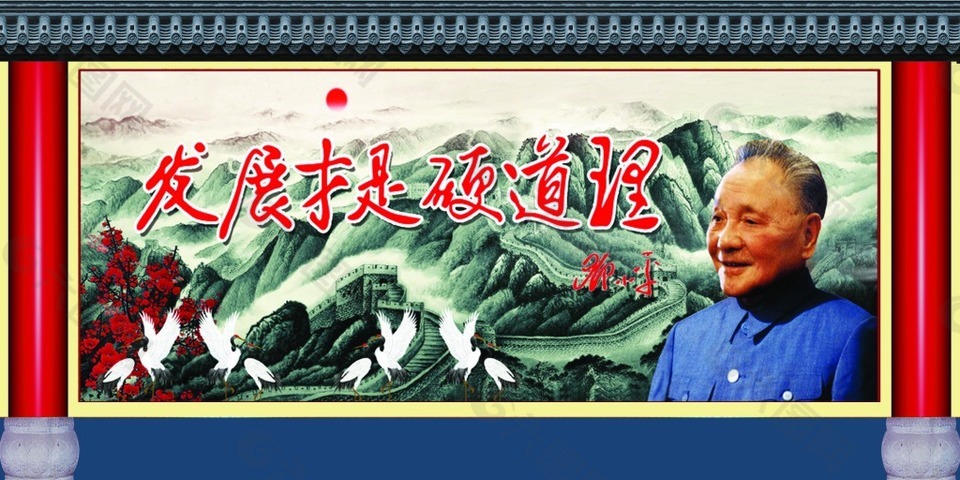

During a heavily promoted tour of key reformist sites in the south of China in January-February 1992, Deng Xiaoping used a series of talks and seemingly impromptu comments to declare that it was high time that the Party moved beyond all the debilitating nitpicking over whether the economic reform policies were by their very nature ‘capitalist’ 資 or ‘socialist’ 社. People could revisit the finer points of ideological contestation in twenty years, but for the moment bold new reforms were urgently required. ‘Development is simply an inescapable necessity’ 發展才是硬道理, Deng announced and he played a key role in engineering the Party’s return to further transformative policies. Although ideological clashes would continue in a milder form, in October 1992, the revised Party Constitution had made it clear that: ‘all erroneous “leftist” and rightist tendencies should be opposed and, although we must remain on guard against rightist deviations, the main emphasis must be on preventing “leftism”.’ In this instance, and according to this line of thinking, ‘rightist deviations’ indicated a lack of policy coherence and perseverance, as well as a tendency to betray Party principles or make questionable compromises. ‘Leftist deviations’ were more pernicious in so far as they resulted in sudden policy lurches, vicious political struggles within the Party and excessive ideological policing. Once more we are reminded of Joseph Stalin’s rejoinder to the question: ‘Which deviation is worse, the Rightist or the Leftist one?’ Stalin: ‘They are both worse!’

In keeping with the policy volte-face of late 1991 and 1992, the ideologues who had felt vindicated by the crushing of the popular protests in 1989 now found themselves sidelined. Gao Di, editor of People’s Daily and a staunch opponent to Deng’s pro-reform message, was relieved of his duties. Deng Liqun, who had published a high-profile series of articles in which he supported the proletarian dictatorship, warned against peaceful evolution and derided the reformist agenda in 1991, was encouraged to focus his energies on a new institute devoted to the history of the Party and the People’s Republic. Hu Qiaomu, the man praised by Deng Xiaoping as ‘the Party’s wordsmith’ and a man whose baleful influence on China’s political life had lasted for over half a century, died in September 1992 having lived just long enough to see the Counter Reforms that he supported with enthusiasm undone. As the Yan’an-era revenant Maoists quit the stage, younger thinkers who were more in tune with the times jostled for influence. One of their number, an academic by the name of Wang Huning 王滬甯, soon found favour with Jiang Zemin and has has played a unique role as an ambidextrous Party thinker ever since. Having served under both Jiang and Hu Jintao, Wang’s exsanguinate mien would become a fixture in the standing committee of the Party’s Politburo under Xi Jinping.

A troubling aspect of the 1992 counter counter reform was the promotion of what looked very much like a new personality cult. Integral to the monumental effort that was required to turn the post-1989 tide, Deng was persuaded to support a propaganda push that lavished praise on his unique role in the Party as the ‘grand designer of the reforms’. The extent and tone of the adulation, however, was in scaled down to the subject’s own diminutive stature. The overblown hosannahs nevertheless contravened Deng’s own earlier warnings about the dangers of leader worship. Party Secretary Jiang Zemin, anxious now to distance himself from the failed supporters of the Counter Reform, was quick to join the sycophantic chorus, one that perhaps was hoping to distract people from the popular ‘Mao Craze’ that was sweeping the country (see Shades of Mao below).

The bid for China to join the GATT and later the World Trade Organization (which it did in 2001) benefitted directly from Deng sidestepping the ideological wrangling at the top of the party. Although the country would be transformed as a result of the new phase of marketised socialism, both in the public sphere and behind closed doors the rancorous ideological debates continued unabated. Over the years, participants not only vied for funding, influence and official approval, they also held out hopes of determining national policy.

The year 1992 ushered in what would, in effect, be a two-decade long ‘Hopium Era’, one characterised by frustrated ventures, wishful thinking, repeated disappointments and false hopes. It would culminate in what I think of as the ‘China Hopioid Crisis’ from roughly 2008 to 2013.

***

The year 2012 marked two decades since Deng Xiaoping’s notional ban on internal Party wrangling over whether the reforms were in essence socialist or capitalist. The end of that year also fortuitously coincided with the investiture of Xi Jinping as the General Secretary of the Communist Party, the first time that one of ‘our children’ 我們的孩子, to use Chen Yun’s term, took the helm of China’s party-state-army.

Within months of Xi coming to power, it was evident to those familiar both with his ideological journey, as well as with the 1989-1992 Counter Reform that, whatever was about to unfold would reflect ideas and policies that resonated with the earlier ideological wrangling, as well as with Xi’s long-term support for a more ‘canonical’ interpretation of Chinese Marxist-Leninist dogma, a body of thought that also embraced Maoism. (Anyone who had read some of the dozens of lugubrious, killjoy essays Xi published in the Zhejiang Daily from 2003 to 2007 had a pretty good idea of what to expect.) In 2020, cognoscenti of Party history would also ruefully note the reappearance of Mainstay 中流, a journal that had promoted an anti-reformist agenda from the time of its founding in 1988 right up until 2001 when it was banned for openly opposing Jiang Zemin’s policies to induct members of the new business elite into the ranks of the Party.

On the eve of the 1989 protests, the political and intellectual worlds of China had been suffused with a sense of anomie. The temper of that era was epitomised by the term yōuhuàn yìshí 憂患意識, ‘a sense of doom’, ‘existential worry’ or ‘all-encompassing anxiety’. It was an expression with ancient resonances for it expressed a kind of anxiety that compelled people of conscience to take action as they tackled seemingly impossible odds. A similar mood of national despair was pervasive also in the early 2010s; this time the premonition of disaster was expressed by people warning that the nation was in disarray due in particular to systemic and unbridled corruption, so much so that ‘the very existence of the party and the nation were imperiled’ 亡黨亡國. As Gloria Davies noted in a review of The Founding of a Republic 建國大業 released to coincide with the sixtieth anniversary of New China in 2009:

‘Mid-way through the story, as he contemplates the defeat of the Nationalists, Chiang [Kai-shek] sighs softly, more to himself than his listening son: “Corruption in the Nationalist Party is now bone-deep. If we fight it, we’ll lose the Party. If we don’t fight it, the nation will be lost, how difficult it all is.” (国民党的腐败已经到了骨子里了,反腐败,亡党;不反,亡国,难啊!). At screenings in China these words were reportedly received with resounding applause and cheers for they were taken as being nothing less than a coded warning to the Communist Party-state about its own endemic corruption.’

In many ways, the national existential worry in the years 2009 to 2012 mirrored that of 1988-1989. This time around, however, the collapse of the Soviet Union two decades earlier had an even more powerful lesson to teach, as did the egregious failures of the United States resulting from its self-inflicted disasters: an endless war on terror and the Global Financial Crisis.

***

***

Prelude to a Restoration

As I have argued elsewhere, since the mid 1990s the Chinese Communist Party, while shoring up its own position as the end point of revolutionary change in the country, had also been engaged in a process of grand historical reconciliation, the origins of which go back to the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and the founding of the Republic of China. (See, for example, ‘China’s Flat Earth: History and 8 August 2008’.) In ‘Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium’, a continuation both of the present essay and of ‘The Fog of Words: Kabul 2021, Beijing 1949’, we discuss the history and significance of Restoration in China today. For the moment, however, let us maintain a focus on the reverberations of the Counter Reform years of 1989-1992 in China today.

In the late 1980s, reformers who were fearful that mass agitation for political change would only serve to benefit the anti-reformist agenda of backward-looking Party stalwarts — leaders who had long warned of the dangers wrought by rapid economic change — promoted the idea of the ‘neo-authoritarian’ 新權威, that is a political leader who enjoyed both substantial state power and a sufficiently liberal vision. Such a figure, it was argued, would be able to guide the country along a path of further fundamental market-oriented economic reform as well as meaningful political change. Two decades later, another claque of intellectuals, this time in the guise of New Marxists who had long opposed market socialism, decentralisation and the threat of social inequality, advocated ‘statism’ 國家主義, a concept that championed the view that only under the aegis of a strong leader would China be able to maintain its economic and strategic independence from the depredations of the imperialism and the US-led neoliberal world order.

Whereas the supporters of enlightened autocracy in the late 1980s had unwisely invested their hopes in Zhao Ziyang, a man of limited political skill, in the first decade of the new millennium, before factional infighting deprived them of their hero, the ‘leftist’ advocates of neo-autocracy flocked to support Bo Xilai, a man with the kind of pedigree long supported by Chen Yun and one whose credentials as an iron-fisted, albeit charismatic, regional caporegime suggested could be the man of the hour.

Both Bo Xilai and Xi Jinping, the ultimate victor in the 2008-2012 power struggle, were preparing to confront the systemic crises that, in many ways, mirrored those of the late 1980s. The issues at stake in the first decade of the new millennium included: independent voices calling for political change, along with support for what were now called ‘universal values’ (even Premier Wen Jiabao toyed with the term!); and, grass-roots civil activism that took heart from the example of the ‘color revolutions’ that had toppled autocratic regimes. Both contenders for Party supremacy were particularly mindful of the increased pressures on China’s economic managers to become more closely enmeshed with the global order, one under the sway of the United States, its allies and their leading corporations; the burgeoning influence of members of China’s home-grown, uberwealthy business elite; the widespread concern about moral decay and endemic corruption; the diminution of the Party’s much vaunted ‘spirit of struggle’ and militancy; enervated party institutions; a faltering historical vision; a crescendo of heterodox views which were finding an outlet in an increasingly independent media; a looming open conflict with the United States; widening social inequalities that were contributing to mass unrest; forms of factionalism that made a mockery of the so-called ‘collective leadership’ of the Party; political rumour-mongering that fed public panic and individuals at all levels of society who offered a running commentary on disarray in the ranks of Party leaders. Added to all this, leaders like Xi Jinping indicated that there was a lack of serious political focus within the Party itself, something demonstrated by the fact that numerous Party cells had abandoned regular political study sessions.

In response to this broad suite of issues in the months leading up to the Eighteenth Party Congress in November 2012, political wonks, advisers and careerists flooded candidates for the top party-state jobs with advice. Yuan Peng 袁鵬, a leading analyst at a Ministry of State Security think tank, publicised his views in an advice paper that July. Yuan told his superiors that China urgently needed to take full advantage of the opportunities presented by the international malaise following the Global Financial Crisis. Under a sagacious leader the situation could well work in China’s favour. With that in mind, Yuan suggested that Beijing had a three- to five-year window of opportunity to get its house in order so as to prepare for an extended struggle with the United States. He called it the ‘Great Game’. ‘In reality,’ Yuan said, ‘the actual challenges facing China are not imminent’:

‘rather they lie five to ten years in the future. The real dilemmas are not global or even regional; rather they will be generated by internal systemic changes and our social ecology. The real threat is not military conflict; it is the problems arising in the non-military arenas of finance, society, the Internet and diplomacy.’

Of immediate concern was the threat to China internally:

‘The US will avail itself of various non-military means to delay or hinder China’s progressive rise. In so doing it will hope to gain strategic advantage, revitalise itself and consolidate its hegemonic position.’

One of the main pathways the US was utilising to pursue its agenda was:

‘In the name of “Internet freedom” transforming the traditional mode of pursuing top-down democracy and freedom. Utilising rights lawyers, underground religious activities, dissidents, Internet leaders and vulnerable groups as core constituencies with the aim of infiltrating China’s grass roots so as to carry out a bottom-up process to create thereby conditions to “transform” China.’

Once he ascended to Party leadership in late 2012, Xi Jinping had at his fingertips a veritable treasure-trove of ideas and political practices honed and refined over decades both by Mao and Deng. Since the 1930s, Party thinkers had melded Stalinist political ideas and practices with millennia of what is known as ‘the art of imperium’ 帝王之術. Xi, having long witnessed first hand the desuetude of his fellow party leaders, and evidently having mulled over his ‘when-I-get-into-power’ plans for years, was now ready to launch a revanchist program all of his own. It shared far more in common with the Counter Reform of 1989-1992 than with the Cultural Revolution. In fact, it was nothing less than a Restoration 中興.

Shortly after assuming power, Xi summed up his approach in a neat formula known as ‘Contra the Two Negations’ 兩個不能否定. In an address to a class at the Central Party School on 5 January 2013, Xi declared:

‘The era of reform must not be used to negate the historical era that preceded it. In the same token, the pre-history of the reform era cannot be used to negate it either.’

不能用改革開放後的歷史時期否定改革開放前的歷史時期,也不能用改革開放前的歷史時期否定改革開放後的歷史時期。

Whereas the early era of the reform period found negative inspiration in some of lessons of the 1950s and 1960s (as well as positive economic ideas from non-Soviet Bloc socialist countries such as Yugoslavia), Xi made it clear that no longer would the ‘first thirty years’, a shorthand for the Mao era of 1949-1978, be set in opposition to the ‘second thirty years’ of reform, that is, 1978 to 2008. He has sought to establish himself as an ideological unifier (not a conciliator), one whose ambition is to subsume and outdo Mao and Deng in ideological as well as geopolitical terms, in particular by unifying the nation’s territory through a resolution of the Taiwan question. In effect, Xi was articulating the basis for policy continuity that would embrace aspects of High Maoism as well as the Counter Reform years of 1989-1992. After all, he said:

‘The Party would not have survived if it negated Comrade Mao Zedong completely. Would our socialist system have survived? No, and if it hadn’t all would have been thrown into chaos.’

如果當時全盤否定了毛澤東同志,那我們黨還能站得住嗎?我們國家的社會主義制度還能站得住嗎?那就站不住了,站不住就會天下大亂。

Xi Jinping revealed his sweeping bureaucratic ambitions early on, something that led me to dub him China’s ‘Chairman of Everything’ in late 2013. In the introduction to the 2014 China Story Yearbook written shortly thereafter, I suggested the ten most obvious reasons why Chairman Xi was in such unseemly haste:

- Chinese leaders have long identified the first two decades of the new millennium as a period of strategic opportunity 战略机遇期 during which regional conditions and the global balance of power enable China best to advance its interests.

- Given his history as a cadre working at various local, provincial and central levels of the government Xi Jinping is more aware of the profound systemic crises facing China than those around him.

- He is riding a wave of support for change and popular goodwill to pursue an evolving agenda that aims to strengthen party-state rule and enhance China’s regional and global standing.

- He faces international market and political pressures that are compelling China to confront and deal with some of its most pressing economic and social problems, in particular the crucial next stage in the transformation of the Chinese economy.

- His status as a member of the Red ‘princelings’, or revolutionary nomenklatura, encourages the personal self-belief if not hubris that his mission is to restore the position of the Communist Party as China’s salvation. Believing in the theory that history is created by ‘Great Men’, he considers himself l’homme providentiel whose destiny is to lead the nation and the masses — a kind of secular Messiah complex.

- Unless he can sideline sclerotic or obstructive forces and elements of the system, he knows he will not achieve these goals.

- He is aware of the seriousness of the public crisis of confidence in the Party engendered by decades of rampant corruption.

- He is sincere in his belief in the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist worldview, which is tempered by a form of revived Confucian statecraft that is popularly known as ‘imperial thinking’ 帝王思想.

- Resistance to reform (including of corrupt practices) by the bureaucracy can only be countered by the consolidation of power.

- The consensus among his fellow leaders that China needs a strong figurehead to forge a path ahead further empowers him.

— from Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Under One Heaven’, in

Shared Destiny: China Story Yearbook 2014

(For more on the background to the Xi Jinping Restoration, see ‘Drop Your Pants! The Party Wants to Patriotise You All Over Again’, a five-part series published in China Heritage from 8 August to 1 October 2018.)

***

It is no small irony that the autocratic style of Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun and their fellow Elders — something repeatedly demonstrated by the fact that they paid mere lip service to constitutional formalities and shared an animus toward free thought, the rule of law, media independence and popular political participation — contributed not only to the rise of Xi Jinping, but also fed Xi’s own political vision and ambitions. Some measure of systemic reform might have enabled Deng and his colleagues to ‘break the cycle’ that Mao had promised to do in his Yan’an days, but barring that Party rule is captive to the swings of its own left-right pendulum. For this, the Eight Elders and their successors are collectively responsible.

We should also remember that Deng-Chen-era policies predicated, under Xi, the eventual betrayal of Hong Kong, ongoing repression in Tibet, the promotion of a monolithic account of China’s ‘spiritual civilization’, the intensification of patriotic education, as well as support for anti-foreign zealots. These areas of policy and Party sentiment enjoy a renovation and intensification today, but it should be remembered that they are also integral to the Mao-Deng legacy bequeathed to Xi Jinping in 2012.

In late 1983 I prefaced my essay ‘Culture Clubbed: dealing with China’s Spiritual Pollution’ with an adage taken from Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis:

‘He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils.’

The cage of autocracy condemns its inhabitants to apply the same old remedies to deal with contemporary problems, be they old or new. This time around, however, in 2021 Xi Jinping may have believed that he was confronted with the same knot of pressures that led Deng Xiaoping to embark on his momentous Tour of the South in 1992. What is different is that he is no Party elder but a cakravartin, one who can turn the world on its axis.

***

***

Liu Xiaobo’s Spectres

In the original editorial note to Liu Xiaobo’s 1994 essay ‘The Specter of Mao’, reproduced below, I remarked that Liu was a social and political critic of no fixed abode. Following his detention as one of the ‘black hands’ accused of instigating the unrest of 1989, Liu was denounced in the national media as a dangerous ‘cultural nihilist.’ Although he was eventually released in 1991, his academic career was over, his writings were censored and he was banned from publishing in China. In the spirit of relentless defiance that characterised his life, Liu produced a steady flow of articles, reviews and critiques for the Hong Kong press. It was interrupted only by further stints in jail and, as soon as he was free, he would continue to write and did so up until he was taken into custody that fateful last time, in November 2008.

In his essay, originally translated for Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (New York, 1996), Liu Xiaobo reserves particular contempt for He Xin 何新, an influential critic-cum-academic promoted by the leading Party ideologue Hu Qiaomu. He Xin had come to fame in the mid 1980s as a result of his colorful attacks on ‘degenerate literature’ and China’s ‘hippy’ cultural celebrities. For a short period after 4 June, He was a policy adviser to Premier Li Peng and a prominent public advocate of muscular patriotism. (See He Xin, ‘A Word of Advice to the Politburo’, 1990) Although He Xin fell from grace well before Liu published his essay in 1994, his ideas, and style, have had a long-lasting influence.

During the Counter Reform years thirty years ago, He Xin gave voice to the kind of anti-foreign conspiracy thinking and wolf warrior bellicosity that is now regarded as a hallmark of Xi Jinping’s China. He Xin also long railed against corruption in the upper echelons of the government, warning that it threatened the existence of the party-state itself. If leaders failed to confront endemic corruption in the party and the army, He argued, China’s ‘rise in the East’ as a new world power would be stymied. Even as He Xin faded from the scene in the early 1990s, a host of others eagerly took his place: they ranged from the rabid nationalists at Strategy and Management and best-selling commercial patriots of vitriolic attacks on ‘the West’, to the preening ‘new left wing’ intellectuals, many of whom not only sported Western academic credentials but also foreign passports and green cards. (For details, see ‘To Screw Foreigners is Patriotic: China’s Avant-garde Nationalists’ (1995); and, ‘The Revolution of Resistance’, 2000, rev. 2010.)

The original title of Liu Xiaobo’s ‘The Specter of Mao Zedong’ was ‘The Maoists in the Communist Party and Deng’s Dilemma—some observations on post-Deng politics’ (中共毛派與鄧的困境——後鄧時代的政局觀察, 《開放雜誌》, 1994年12月). Liu and I had known each other for nearly ten years. I sought him out in Beijing after having read his raucous critique of contemporary Chinese culture that had sent shockwaves through the arts world in the summer of 1986. He agreed to be interviewed for The Nineties Monthly, a Hong Kong journal to which I was a regular contributor. Even as he was trying to finish his doctorate from the mid 1980s, Xiaobo wrote furiously, and copiously, about Chinese culture, intellectuals and politics. From 1989, he would achieve renown as a prominent political activist, dissident and, eventually, a Nobel laureate. Detained in late 2008 for his role in promoting ‘Charter 08’ and accused of ‘inciting subversion of state power’, he was sentenced to eleven years in jail. It was his fourth, and final, prison term. Although he was awarded the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize, Xiaobo died in custody in July 2017.

Shades of Mao

I started collecting material on popular yearnings for Mao in music and literature in the mid 1980s. It was not until the fully blown popular, and commercially profitable, Mao cult appeared in the early 1990s, however, that I decided to compile a book on the subject. In ‘The Irresistible Fall and Rise of Chairman Mao’, the introduction to Shades of Mao, I observed that:

‘Deng had been able to shunt aside and move beyond the festering abscess of the Cultural Revolution and deny the legacy of Maoist extremism without ever really finding an effective treatment for the ills of Chinese political life.’

‘Perhaps in the future in China the Mao revival itself can be revived,’ I mused:

‘Mao, at least, will continue to be a figure whose varied legacy can be drawn on, reworked, modified, and exploited to suit the exigencies of the day. This is something Mao had perceived, albeit in narrow political terms, in the famous letter he wrote to Jiang Qing in July 1966. In it Mao speculated on his posthumous fate:

‘I predict that if there is an anti-Communist right-wing coup in China they won’t have a day of peace; it may even be very short-lived. That’s because the Revolutionaries who represent the interests of over 90 percent of the people won’t tolerate it. Then the Rightists may well use what I have said to keep in power for a time, but the Leftists will organize themselves around other things I have said and overthrow them.’ (my translation)

‘Rightists and Leftists—not to mention activists on all points along the political spectrum—have been engaged in a tussle over the legacy of Mao ever since…. we are reminded of Ryszard Kapuscinski’s observation on Iran: “A dictatorship … leaves behind itself an empty, sour field on which the tree of thought won’t grow quickly. It is not always the best people who emerge from hiding, from the corners and cracks of that farmed-out field, but often those who have proven themselves strongest.” ‘

— from Shades of Mao, pp.50-52

The title I decided to use for Liu Xiaobo’s essay — ‘The Specter of Mao Zedong’ — was inspired by ‘A Specter Prowls Our Land’ 一個幽靈在中國大地遊蕩, a poem by the Sichuan writer Sun Jingxuan 孫靜軒 published in 1980 which contains the lines:

‘Ancient China! A loathsome specter

Prowls the desolation of your land …

The specters come, the specters go,

inhabit this man’s corpse, that man’s soul.

Your vast domain breeds feudalism.’

(After having been taken to task for the poem, Sun soon published an abject, although patently insincere, self-criticism.)

In November 1988, Liu himself observed that:

‘Seen solely within the context of Chinese history, Mao Zedong was undoubtedly the most successful individual of all. Nobody understood the Chinese better; no one was more skillful at factional politics within the autocratic structure; no one was more cruel and merciless; none more chameleon-like. Certainly, no one else would have portrayed himself as a brilliant and effulgent sun.’

In 2021, perhaps it is too early to say if and when the present cascade of adulation for Xi Jinping will also come to include praise for his heliotropic leadership.

— GRB

***

Part II

The Specter of Mao Zedong

Liu Xiaobo

Translated by Geremie Barmé

The specter of Mao Zedong has continually haunted Deng Xiaoping and his Open Door and Reform policies. The specter of Mao doesn’t simply inform the attitudes of the Maoists among the Party leadership, it also has a mass following among the people. On this issue those at the top and those at the bottom [of society] are united: they deploy Mao Zedong to oppose Deng’s Reforms. The spirit of Mao is the most powerful weapon in the arsenal of Maoists in the upper echelon [of the Party]. Mao is also the symbol that the masses use to express their frustrations. It would appear that apart from the present policies pursued by the Mainland government there are no alternative, viable political resources for people to rely on apart from the heritage of Mao Zedong. This has been particularly evident since the Massacre of 4 June [1989]. Now most people feel that Western political models are, in the case of China, both impractical and dangerous. What we are presently seeing is the combination of nationalist currents of thought with a nostalgia for the Maoist past. We are being drawn back to the age of Mao Zedong.

Certainly, the Open Door and Reform policies of Deng Xiaoping took as their starting point a complete negation of the Cultural Revolution and a betrayal of the Maoist line. In the last decade or so China has experienced massive changes and the country’s fast-track economic development has astounded the world. Consumerism and hedonism have made people feel richer. It seems as though nothing can stop the ‘peaceful evolution’ that is going on in China. But nobody can afford to forget the following facts: our economic takeoff has not changed the one-party dictatorship created by Mao Zedong; the improvement in the standard of living has not led to increased human rights; the market economy is not predicated on a legal structure based on private property; every political movement strikes terror in the hearts of the new rich; the popularity of karaoke bars and the flood of violent and pornographic literature has not enhanced the status of freedom of speech; industrial reform that has led to the separation of Party and industrial management and the conversion of state industries into companies has not given the masses any greater opportunities or rights to participate in the political life of the nation. … This is the true legacy of Mao Zedong.

Rapid economic development has exacerbated various social antagonisms and brought them to the fore. It has also led to greatly increased public dissatisfaction and frustration. Once Deng Xiaoping effectively blocked any attempts at democratic political reform people increasingly turned to nostalgia as a means of expressing their unhappiness with the state of affairs. People outraged by overt corruption and the activities of official speculators who have become wealthy overnight only too readily think of how Mao Zedong overthrew Capitalist Roaders in the Party and warned of the need to purge bureaucrats from the government. They recall fondly the incorruptible Party of the Maoist past. The people who have been cast to the bottom rung of the economic ladder as disparities in income increase, as well as those who have not benefited from the redistribution of wealth that has taken place, recall with longing the egalitarianism and social justice of the past. Although poverty was the hallmark of that age, at least everyone was equally impoverished. People did not feel as lost and disenfranchised then as they do today. Nor did they feel they were the victims of such social injustice. Unemployed or semi-employed people as well as workers in state enterprises who are no longer being paid will recall their former exalted position under Mao as the masters of society. They remember the iron rice-bowl that assured them an income for life and the Party organization that took care of them from cradle to crypt. The people who witness in terror and disgust the flood of itinerant workers swelling the population of the cities will recall that under Mao there was a strict household registration system that kept the peasants bound to the land. As for the peasants who have been forced to abandon the land they look forward to another peasant leader like Mao Zedong who will lead them to overthrow the landlords and divide up their property just as Mao did. The former power-holders, from high to low, who have retired or who have been forced aside will remember how, under Mao, they were assured power for life. People dissatisfied with the increase in crime, the spread of pornography and prostitution and the production of shoddy and bogus goods think of the innocent and pure days of Mao…. In comparison to these very practical and utilitarian views, the dissidents who were purged after 4 June and who still oppose the government have little to offer the masses. Their manifestoes and petitions have little impact on the power-holders especially in comparison to workers’ strikes, peasant riots, fluctuations in the stock market and violent crime. At the slightest hint of activity the organs of the proletarian dictatorship go into operation and crush all opposition. The dissidents have absolutely no impact on the society as a whole.

We are faced with an absurd social tableau: the poverty of the Mao age emotionally satisfying and exciting, it made people sing with joy although the social ambience was stultifyingly pure. The wealth generated in the age of Deng, however, has made the Chinese feel impotent and disgruntled. The social scene is chaotic to the point of complete degradation. On one hand, we have a peasant leader who murdered tens of millions of people and turned hundreds of millions into pliant slaves, but he is still deeply missed. On the other, is the second generation leadership [Deng, et al.] which rehabilitated countless numbers of unjustly condemned people and which has given the Chinese unprecedented wealth. Yet these people are the object of mass discontent. In my opinion, the person chiefly responsible for this ridiculous situation is not Mao Zedong, nor even the Chinese, but none other than Deng Xiaoping himself.

Since coming to power Deng has been caught in a bind. The Maoists within the Party as well as the malcontents outside it have criticized him for taking the Capitalist Road. The Reformers in the Party (including people who called for political reform like Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang) as well as the dissidents in the society at large have attacked him for upholding authoritarian rule and for being a dictator. Caught in a tussle between these two forces Deng has been powerless to respond to the attacks of the Maoists. He has constantly compromised with them and been forced to do so because his Four Basic Principles are used by the Maoists to bolster and protect themselves. No matter how outrageous they become they have never been treated like the dissidents. On the contrary, there has been an escalation of the pressure Deng has brought to bear on radical reformists. First, they were named in the media and criticized, then came expulsions from the Party and dismissal from office. Finally, he resorted to using tanks and mass jailings to silence them. As Deng upped the ante in regard to the Reformers, the Maoists took advantage of the situation to increase pressure on Deng.

The Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign in 1984 and the Anti-Liberalisation Campaign of 1987 resulted in the fall of [Party General Secretary] Hu Yaobang from power and the purging of a large part of the reformist élite. [Note: The Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign was a short-lived cultural and ideological purge launched in late 1983; the Anti-Bourgeois Liberalisation Campaign of early 1987 was only marginally more effective, although it did result in the resignation of Hu Yaobang, a renewed crackdown on the media and the expulsion of a number of outspoken figures from the Communist Party.] Those purges were, for the Maoists, relatively moderate. The bloody massacre of 4 June sealed the fate of Zhao Ziyang and his plans for political reform as well as leading to the ouster of large numbers of élite intellectuals, not to mention the murder of pro-Reform citizens. What followed was a massive Maoist purge in all realms: political, economic, and ideological. People had to make self-criticisms before they could be let off the hook. China now pursued a policy of ‘preventing peaceful evolution’ and propaganda about foreign imperialists plotting to overthrow the Party not heard for many years was trotted out once more. [Note: Deng Xiaoping claimed that the activists who were supposedly behind the student demonstrations of 1989 were agents of enemy powers (that is, the U.S.) who were hoping to turn China into a bourgeois republic that would be a vassal state or commercial dependency of the West.] A ‘neo-conservatism’ led by He Xin spread throughout the nation. He Xin’s sophistry even managed to fool many university students who had experienced 4 June. [Note: He Xin was active in the first few years after 4 June and he reportedly impressed many university students when he spoke at campuses in Beijing presenting his unabashedly conservative views of contemporary events. He Xin and Liu Xiaobo had been openly hostile from the late 1980s. Regardless, He was hardly single-handedly responsible for the ‘conservative’ wave of the early 1990s.] The high-level Maoists within the Party now blamed 4 June on Deng’s capitalist policies and said they had encouraged bourgeois liberal elements within the society.

Meanwhile, among the masses, Mao badges reappeared everywhere. Old songs in praise of Mao reverberated throughout the land and books, films and tele-series related to Mao became all the rage…. Suddenly the whole nation seemed to be possessed by a desire to return to the Maoist past. Deng’s prestige was clearly under threat.

In early 1992, Deng Xiaoping responded to all of these pressures by going on his ‘tour of the south,’ reaffirming his policy that Reform policies must continue for another century. This led to a new high tide of Reform. Although the Maoists were forced into retreat they kept up the pressure in both the political and ideological arenas. While consumerism and money making swept the nation, the Maoists still issued warnings against peaceful evolution. Although the authorities published the third volume of Deng Xiaoping’s Selected Works at the time of the Mao centenary [in 1993] in an attempt to divert interest in Mao, in the hearts and minds of the masses Mao remains the greatest modern leader of China.

In 1994 the various social tensions in China became more evident and violent. Party Central took measures to strengthen its power and control over local Party organizations. About this time the book China Through the Third Eye was published and in July a conference, ‘Socialism and the Modern World,’ was held in Beijing.[Note: this book created a sensation when it appeared in the spring of 1994 and was widely discussed before eventually being banned. The conference was organized with the support of the Beijing Capital Steel Corporation.] Both were highly critical of Deng’s policies and expressed nostalgia for the Mao years. The popular impact of these two events goes without saying; but it is interesting to note that the authorities took them seriously as well. This is an indication that the types of views expressed [in both the book and at the conference] have a wide-spread appeal.

Deng’s greatest achievement may well have been that he was able to break free of the Mao era and abandon ‘class struggle’ in favour of economic development. But Deng’s greatest dilemma has resulted from the fact that he persevered with Mao’s political system and was unable to change fundamentally the nature of authoritarian rule in China. Nor could he expose the disasters that Mao’s rule created. On the contrary, by pursuing his Four Basic Principles, Deng maintained Mao as the ruling icon of the Party and the nation. Particularly, in his autumn years, Deng has re-enacted the tragedy of Mao himself.

It may well be that as a Party member who worked under Mao for decades Deng was congenitally incapable of cutting the umbilical cord to the Chairman. Despite his own suffering under Mao and the horrors wrought on the Chinese people by him Deng could not bring himself to betray him entirely. Deng’s greatest tragedy has been his inability and unwillingness to develop a Reform strategy that could supersede Mao Zedong.

China has lived under Reform for sixteen years now; still the specter of Mao haunts the land. Those who are disgruntled with the present state of affairs find resources of confidence and strength in the legacy of Mao. Every time Reform suffers a setback, whenever social tensions are exacerbated people from the highest echelons of the Party to the broad masses pay homage once more at the altar of Mao Zedong and seek to negate the policies of Deng Xiaoping. People ignore the fact that the social problems of today are, in essence, remnants of Mao’s rule. They are oblivious to the fact that any sustainable effort to transform China must negate Mao’s legacy. And still they worship him.

In reality, the reason that leftist thinking repeatedly resurfaces in China and finds support is that Deng Xiaoping has allowed it to do so. The Maoist system that he has continued to promote is the greatest enemy of the Reforms on which he embarked. The 4 June Massacre served only to entrench the contradiction between the Four Basic Principles and the Reform policies.

After Deng, it will be the banner of Mao Zedong that may be unfurled once more to stabilize China. Maoist socialist egalitarianism may well be used to pursue policies of social equality and clean government. For in these policies the authorities may find a way of dealing equitably with mass disaffection. But that will mean that China will fall back into the vicious cycle of history.

— November 1994, Beijing

***

Source:

- Geremie Barmé, Shades of Mao: The Posthumous Cult of the Great Leader (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe), 1996, pp.277-281

***

Related Material:

- ‘Confession, Redemption and Death: Liu Xiaobo and the 1989 Protest Movement’ (1990), reprinted in China Heritage Quarterly, March 2009;

- Liu Xiaobo interview in the 1995 documentary film The Gate of Heavenly Peace;

- Liu Xiaobo, ‘Bellicose and Thuggish — China Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow’ (July 2002), this translation, originally published in 2012, was reprinted by China Heritage in January 2019; and,

- Geremie R. Barmé, ‘Mourning’, China Heritage, July 2017