Viral Alarm

‘But I’m not guilty,’ said K., ‘there’s been a mistake. How is it even possible for someone to be guilty? We’re all human beings here, one like the other.’

‘That is true’, said the priest, ‘but that is how the guilty speak.’

― Franz Kafka, The Trial

***

Xiaonan, We Are Just as Guilty!

瀟男,我們與你同「罪」!

Guo Yuhua

郭於華

- She ran [with her husband] a small cultural publishing house. What crime is there in that?

- She organised academic and cultural symposiums. What crime is there in that?

- She arranged intellectual salons, invited people to meals and thought up various group entertainments. What crime is there in that?

- She protested against the persecution and detention of a friend framed for having spoken out. What crime is there in that?

We have all been involved in the same activities. The only difference is that Geng Xiaonan has been more active, more creative and more successful in all respects.

Xiaonan: if you are guilty of anything, then we are just as guilty as you!

經營文化出版小公司,何罪之有?

舉辦學術文化講座討論,何罪之有?

組織沙龍、聚餐、娛樂活動,何罪之有?

為因言獲罪被污名被抓捕被迫害的朋友呼號吶喊,何罪之有?這類事我們都做了,只是瀟男做得更多、更藝術、更漂亮。

你若有罪,我們與你同罪。

To the government agencies concerned:

- By detaining Geng Xiaonan and her husband, you have broken the law!

- By willfully neglecting to notify family members, by condemning elderly parents to seek out news about what has happened to their loved ones, you have broken the law!

- By refusing to the recognise the power of attorney those detained signed with their lawyer, you have broken the law!

- By resorting to spurious excuses to prevent those detained from meeting with their legal counsel, you have broken the law!

- By denying legal counsel the right to meet those detained at a time that yourself had appointed on the sudden excuse that the detained were ‘being interrogated’, you have broken the law!

- By blocking legal counsel the right to wait until the questioning had been concluded so they could meet with the detained, you have broken the law!

Are you only there to violate the law?!

有關部門:

你們為此刑拘瀟男夫婦,你們違法!

你們不按規定通知家人、讓耄耋之人四處尋人,你們違法!

你們不承認當事人簽約的律師,你們違法!

你們百般阻撓律師會見當事人,你們違法!

你們在約定會見時間以「刑警提審」不讓會見,你們違法!

你們在律師提出等候審完見人依然不讓會見,你們違法!你們是為違法而存在的嗎?

— trans. G.R. Barmé

***

Note:

- Guo Yuhua 郭於華 is a professor of sociology at Tsinghua University. See ‘J’accuse, Tsinghua University!’, China Heritage, 27 March 2019

***

***

In the editorial introduction to ‘Geng Xiaonan, a “Chinese Decembrist”, and Professor Xu Zhangrun’, (China Heritage, 10 September 2020) we quoted Jerome A. Cohen, Faculty Director Emeritus of New York University’s U.S.-Asia Law Institute, to the effect that:

‘This week saw the detention in China of Geng Xiaonan, a well-known Beijing publisher and outspoken supporter of the famously harassed former Tsinghua University law professor Xu Zhangrun. Geng is reportedly destined for “very heavy” punishment, not the 15 day maximum in an unpleasant detention cell usually imposed for minor offenses not deemed sufficiently grave to constitute a “crime.” The initial “illegal activity” charge against her is vague enough to cover either her publishing business alone or her open support for Xu or, very likely, both. How long her husband, detained with her, will be held will depend on how important his interrogation seems to her case.’

— from ‘The Vagaries of Crime and Punishment in China’,

The Diplomat, 15 September 2020

Following the formal announcement of the detention of Geng Xiaonan and her husband, Qin Zhen, on 12 September, Franz Kafka’s shade made an appearance:

Despite the fact that Geng had signed a Power of Attorney with Shang Baojun 尚寶軍, a well-known rights lawyer in Beijing, the authorities now informed him that to be able to represent the accused he would require her in-person confirmation of his status. However, since Shang was denied access to his client — despite having been allocated a time for a formal meeting with her — Geng and her husband were cast into a legal limbo.

On 16 September 2020, Shang Baojun was informed by the police that the couple had been denied bail.

People familiar with the situation reported that, on 18 September, having now been able to meet with Geng Xiaonan’s mother and younger sister, Shang Baojun had secured a new Power of Attorney that confirmed his role in the proceedings. However, for him to see the incarcerated Geng, he still had to apply for permission online. The Haidian Public Security Bureau, where Geng and her husband are being held, placed strict limits on access to prisoners, limiting it to twelve prisoners per twenty-four hour period. Since the number of prisoners far outnumbers this small quota, the lawyer had no choice but to vie for one of the twelve places in the early hours of each new day. Competition is fierce and, for the time being, he has been unable to secure a number.

As a result, Geng Xiaonan and her husband remain without formal legal counsel or protection. At the time of writing, it is uncertain how long this absurd state of affairs would continue.

***

Make no mistake:

Geng Xiaonan is a hostage and her detention is a threat. The Beijing authorities arrested her on the pretense of investigating ‘business irregularities’, but their aim was to exact revenge on her, silence and punish Xu Zhangrun, and threaten those whom she has supported over the years.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

20 September 2020

***

***

Ai Xiaoming on Geng Xiaonan:

- Ai Xiaoming 艾曉明, ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Dance of Defiance’, China Heritage, 16 September 2020

Bei Ming on Geng Xiaonan:

- Bei Ming, ‘Geng Xiaonan, a “Chinese Decembrist”, and Professor Xu Zhangrun’, China Heritage, 10 September 2020

- 北明,華盛頓手記, ‘耿瀟男的閨房話’, 《自由亞洲電台》, 2020年8月11日

Geng Xiaonan on Xu Zhangrun:

- 北明,華盛頓手記, ‘耿瀟男詳說許章潤(上)’,《自由亞洲電台》, 2020年7月24日

- 北明,華盛頓手記, ‘耿瀟男詳說許章潤(下)’,《自由亞洲電台》, 2020年7月30日

Bei Ming on Xu Zhangrun:

- Bei Ming 北明, ‘Let the Record Show — an Account of Xu Zhangrun’s Protest and Resilience’, China Heritage, 30 August 2020

Bei Ming and Xu Zhangrun on Geng Xiaonan:

- ‘瀟男夫婦9月10日被失去自由,羅列經濟罪名抓捕。這是她自己預感到要被動手前的徵兆,接受亞洲自由電台北明女士的採訪,做的自述。有愛心的朋友請幫著一起傳播呼籲停止對她們的加害和恢復對她們的人生自由’, 《庚子自由談》, 2020年9月11日

Related Material:

- ‘中國民營企業出版人耿瀟男在洛杉磯和華語媒體會面’,《Amtv全美電視臺》, 2018年11月9日

- The Editor, ‘無可奈何 — So It Goes’, China Heritage, 6 July 2020

- The Editor, ‘Xu Zhangrun & China’s Former People’, China Heritage, 13 July 2020

- Xu Zhangrun 許章潤, ‘A Letter to the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University’, China Heritage, 19 August 2020

- Guo Rui, ‘China detains publisher who voiced support for Communist Party critic Xu Zhangrun’, South China Morning Post, 10 September 2020

- 狗哥, ‘耿瀟男,陳秋實背後的女士!‘, 《看中国的狗哥DogChinaShow》, 2020年9月11

- ‘美國政府對耿瀟男夫婦被捕一事表關注’, 《自由亞洲電台》, 2020年9月17日

Geng Xiaonan’s ‘Gengzi Free-range Talks’:

- 《庚子自由談》,耿瀟男主持. This series offers an eclectic range of ideas from some of China’s most prominent, if embattled, thinkers, academics and cultural commentators, curated and introduced by Geng Xiaonan

‘It is not necessary to accept everything as true, one must only accept it as necessary.’

‘A melancholy conclusion,’ said K. ‘It turns lying into a universal principle.’

— Franz Kafka, The Trial

Chronicling an Arrest Foretold —

A Personal Exchange with Geng Xiaonan

耿瀟男的閨房話

Geng Xiaonan and Bei Ming in Discussion

Washington Notes, Radio Free Asia

自由亞洲·華盛頓手記

Translated & Annotated by Geremie R. Barmé

Introduction

Bei Ming

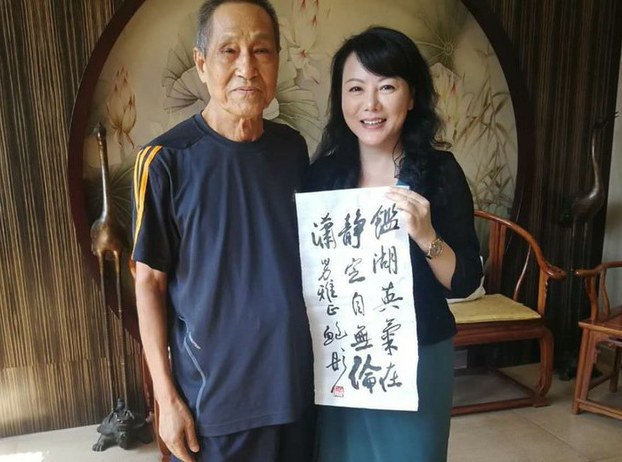

The following material is taken from an ongoing exchange that I had with Geng Xiaonan, a noted Chinese publisher and the host of a number of highly regarded independent cultural and artistic salons in the People’s Republic of China. Our ‘conversation’ (which consisted of back-and-forth voice messages) followed on from the formal interviews that I conducted with Geng regarding the status of Professor Xu Zhangrun in Beijing. As a result of the original interview listeners interested in the broader issues of freedom and justice in China today also expressed concern about Geng Xiaonan herself. Many were deeply impressed by the values that she espoused, as well as being moved by her courage and thoughtfulness. Of course, they are now also deeply concerned about her personal safety.

Since I recorded the original interviews we stayed in touch and, because of the value of our exchanges, I sought her permission to record her comments. With her encouragement, I made a another program on the basis of our discussion, our ‘private conversation’ that she agreed could be made public. The following is my transcription of that recorded material.

In our exchanges, Geng’s responses to my observations and questions touched not only on matters of personal, even private concern, but also embraced broader social issues. With Geng Xiaonan’s kind permission, below I share a selection of her comments with my listeners. I believe that we are fortunate to be able to hear more from this powerful female voice, one that echoes through the concrete valleys of China’s capital city, Beijing. As she continues to forge a path forward, Geng Xiaonan offers us further insights into her private thoughts. Thereby we gain some glimpses of her undaunted spirit.

Our recorded exchange was not done in the usual, more formal style of ‘Washington Notes’ in which interviewees respond to well-researched questions. Rather — to use an expression from The Bible — this ‘rib of Adam’ is responding to the fate of Man. It is an informal exchange and, as such, I ask you to forgive our casual tone.

主持人(北明) :各位朋友,這次節目為您播出一次計劃之外的話語,幾段大陸民間文化學術藝術界沙龍主持人和出版人耿瀟男與北明私下聊天的語音。

自上兩次華盛頓手記播出耿瀟男詳說許章潤的正式訪談之後,中國嚮往公義的人們除了進一步關注許章潤先生其人其事,也開始關注為此接受採訪的耿瀟男,關注她的價值、她的義勇、她的思慮,以及她的安危。於是有了這些訪談之後的私下溝通,而耿瀟男回复北明的話語,其價值和意義漫出了她的閨房,超越了私人畛域,具有廣泛的社會性。經她同意,北明將這些與她私下的溝通中的部分內容與您分享,我們藉故一起看看在中國皇城北京的水泥叢林中踏步前行的這位女子,藏在自己閨閣中的她的靈魂質地和精神境界。

我強調一下,這次播出的不是一次正襟危坐的、準備好要公之於眾的媒體訪談,這是——按照聖經的說法——一根男人身上的肋骨與另一根男人身上的肋骨在閨房裡的私下聊天兒。所以,請不要對這些話語表述的精煉程度過於苛責。

***

Geng Xiaonan: Sister, lately whenever I go out I know that I’m being followed, either by car or on foot. I’m in no doubt whatsoever that they definitely have me in their sights. And they know just what they are doing. For example, no one follows me if I’m only going to do some shopping at the supermarket; or, if my husband and I go out for a meal they’ll leave us alone. But if I’m going to meet with members of the international media — just look out: there’ll definitely be a vehicle tailing me. Or, say I have arranged to meet with Professor Xu Zhangrun, the second I step out the door they’re right my tail. That’s why I say their technique is impressive.

耿瀟男:姐姐,就是我出門有車跟着、有人跟着這件事兒,就說明他們百分百的掌控我了。他們特別準確,比如說我出門去超市,沒有人跟着,我跟老公出門出去吃飯,沒有人跟着。但是如果說今天哪個外媒約我了,哎——你看,一出去就又車跟着我。如果今天我跟許先生我們約好了要見面,哇!那一出門就有人跟着我了。所以說他們非常準確。

Bei Ming: Xiaonan, I am truly concerned about your personal safety. Shouldn’t you perhaps rein it in just a little? Maybe try and avoid going out too often and keep in touch with people by phone. If you are being followed — be it by car or by some ‘shadow’ — that means that you are in a precarious situation and that they are on to you. They might not resort to some ideological sanction when it comes to dealing with you. (As Bei Ming notes: ‘that’s to say, there’s no need for overt political repression; they can simply arrange something like a “traffic accident”.’) They can always think of some other way to hurt (kill) you. That’s why I’m pleading with you not to be too ‘thick’, or ‘nerdish’. You talk about your ‘ambition to soar’. but don’t let your aspirations drag you down.

北明:瀟男我有點兒擔心你的安全,你自己是不是稍微收斂一點兒,啊?少出門兒,多打電話就行了吧?出門兒如果有車跟你,有人跟你,那很危險,他們會使壞。這個人身安全,不一定就直奔意識形態(注:意思是不一定用政治手段打壓,而會製造交通事故等),他們找一個別的(辦法),就把你那個什麼了(害死了),所以你別,你別“二”啊,你說那“而起沖天”,你自己別“二氣沖天”啊。

Geng Xiaonan: You’re right, I shouldn’t be too ‘thick’ [obdurate]. Absolutely, spot on! There truly is no reason to sacrifice oneself needlessly. Of course, I agree. But then, when you are confronted by the overwhelming power of the state, we simply have no escape. There’s nowhere to go; they control every aspect of your existence. They have sway over our families and relatives, our assets and income, our … …

耿瀟男:嗯,姐姐你說的就別犯“二”,對對,是是是,就是說我們沒有別要做無謂的犧牲,哈,這一點,肯定的。但是有的時候也確實是這個國家機器太強大了,我們也跑不到哪兒去,他們控制了我們的所有,控制了我們的親人,控制了我們的財政,控制了我們……

Bei Ming: I know, and that is the broader context of all of this: there is no escape, how could there be? But, please, I beseech you, try and play it smart, be canny about how you go about things.

北明:我知道,這大局是這樣,躲是躲不掉,你怎麼躲!但是千萬千萬,你還是機靈一點兒、機智一點兒啊。

Geng Xiaonan: In Beijing at the moment under the cover of responding to the coronavirus epidemic the authorities have been successful, and I would say holistically instituted what Mr Xu has described as ‘Big Data Totalitarianism’ [see Xu Zhangrun, ‘Viral Alarm — When Fury Overcomes Fear’,ChinaFile, 10 February 2020]. So, that means we are faced with a situation in which whenever we leave the house, whether it be to a café, a restaurant, a teahouse, any retail outlet at all, or an office, in fact anywhere in public at all, we need to register our movements using a ‘digital health tracer’.

That means, whenever you go out your whole itinerary will be collected in a data sweep, one that allows them to identify with frightening precision every stop you’ve made. Of course, you’re free to leave your mobile phone at home, but then all you can do is wander the streets, because you won’t be able to perform any everyday commercial or consumer activity.

耿瀟男:現在北京,他們借 著疫情,在2020年借著新冠疫情的這個借口,成功地、整個地對全民實現了——許先生的原話是——“大數據極權”,“大數據極權”。那姐姐我們現在面臨的狀況就是,我們一出門,我們要去任何咖啡廳,任何餐廳、任何茶館、任何商(業)超(市)系統、任何寫字樓,我們去到任何一個公共的地方,我們都需要用手機去進行健康碼的掃碼。那麼你出去轉一圈,你的這個整個的大數據,能夠精確的掃描到你去了哪一些地方,非常的精確。如果我不帶手機出去,也可以,那你出門就只可能在路邊兒走一走而已,你進行不了任何日常生活的購買行為呀、消費行為。

So, the coronavirus has enabled the Communists to impose a skein of Big Data Totalitarian surveillance that has all of us in its sights. We are all prey to this reality. If you enter a mall, for example, there will be a data reader set up at the entrance where you have to register using your phone and then, no matter what business you visit inside the mall — a restaurant, for example — you’ll have to register again. After that, if you happen to pop into a teahouse you’ll have to scan your phone again. That’s why there is, quite literally, no escape. You can’t run and you can’t hide.

Another aspect of the success of the Communists is that, say, although Wuhan is declared virus free, when a case is detected in Beijing then it might go from being a low-risk city to becoming a city of medium risk. Then, when the cases in Beijing go down, maybe two cases are detected in Dalian. That means within China as a whole, they have a ready-made excuse to maintain their digital surveillance at all times, everywhere. The upshot of all of this is that your basic rights, your privacy, as well as your rights as a citizen to move around, relocate, pursue job opportunities, that is to say, all of the most basic freedoms and rights, now fall prey to their control.

這次新冠疫情,執政黨更加成功的對我們進行了一個大數據極權的一種完全的掌控。整個我們目前就更加淪落到這樣一個地步。我們進到一個大mall 裡面,這個大mall 的門口,我們必須要進行掃碼,要登記,從這個大mall進去在這個Building裡面,進到某一家餐館,餐館又要進行掃碼登記。然後從餐館出來,我們要進到一個茶館裡面,又要掃碼登記。所以說真的是逃無可逃啊姐姐,目前我們真的是逃無可逃。而共黨更加成功的是,比如說今天武漢的疫情剛解,他又給你報道說,北京的疫情又從低風險地區進入到中風險地區,北京又發現一例。那也許北京的疫情下去了之後,說大連又發現了兩例。那麼全國就完全是有借口,不是這兒起疫情,就是那兒起疫情。這種對你的人權、隱私權,對你這個公民的自由的遷徙、自由流動、自由的去勞動獲得生存成本的這樣一個自由,是完全的,就完全的淪陷了!

Bei Ming (addressing the audience): Such a system whereby your phone, which has to be registered under your real name [and linked to a national digital ID card], is used to record all the details pertaining to a person’s movements. The instant the QR code on your phone is scanned everything about you is recorded: your full name, age, gender, job, home address, people you are with, as well as the time and place of your activity. What exactly is the extent of this kind of go-to-whoa monitoring? According to statistics posted by China’s own Ministry of Information and Industry, by December 2015, over 1.306 billion people of the country’s population of 1.374 billion had access to a mobile phone, that’s 95.5 percent of the country.

That was five years ago, and some 29.6 percent of those users were on the 4G network (see ‘中國手機用戶數衝破13.06億戶 4G滲透率達29.6%’, 26 January 2016). In other words, theoretically, apart from the roughly one million Uyghurs confined in ‘re-education facilities’, and people in isolated mountainous regions or in the distant plateaux, nearly everyone in China can be monitored by the electronic surveillance system. The authorities stipulate that everyone has to allow access to their private lives and movements on the grounds of preventing the spread of malware and software viruses. In effect the whole country is shackled with by personal tracking devices. Would any other normal — and here I mean modern, civilised nation — anywhere in the world impose such a system on the grounds of dealing with coronavirus?

主持人(北明):利用私人手機和實名制登記制度,在私人在所到之處掃碼,記錄下每一個私人居家之外的行跡,包括這個人的姓名、年齡、性別、身份、住址、同行者、時間、地點等。這種從頭到腳掌控普遍到什麼程度呢?據中國工信部數據顯示,截至2015年12月底,中國手機用戶數量在當時全國13.74億人口中,衝破13.06億戶,手機用戶普及率達到95.5部/百人。這是5年前,2015年的統計(注:引自 風傳:“中國手機用戶數衝破13.06億戶 4G滲透率達29.6% “, 2016-01-26)。也就是說,理論上,除了被關在「再教育集中營」裡的一百萬新疆維吾爾族人以及極為邊遠山區、高原的少數人口,中國幾乎百分之百的人口的戶外活動均在被監控中。以防範病毒為由,利用現代高科技手段和你手中的手機,收繳你的隱私,監督你的行動,給你在監獄外面戴無形的手銬腳鐐,世界上有任何其他國家——我指的是文明國家,文明的程度不高的國家也包括在內——用這種方式控制新冠疫情的嗎?

Geng Xiaonan: What’s even more terrifying is that the average Chinese is fairly clueless when it comes to their basic rights and they are not tuned in to such things as privacy. At the moment you can see how people are simply accommodating themselves to things as they unfold without question, overall they accept that it is all part and parcel of the coronavirus emergency.

耿瀟男:而且更可怕的是,姐姐,因為中國人本來對這種人權,這種意識及淡薄,對這種隱私權的意識就淡薄,而且好像目前還這樣的一種情況安之若素,還覺得這是在防空疫情。

Bei Ming: After we broadcast that episode [in two parts, titled ‘Geng Xiaonan’s Insights Into the World of Xu Zhangrun’] there has been a strong reaction and people here at Radio Free Asia started paying attention to you. So, all in all, that’s a good thing. They even suggested that I keep on eye on your unfolding situation.

北明:這個節目(指“耿瀟男詳說許章潤”)出來以後,反響越來越多,公司裡也因為這個節目開始關注到你了。所以,算是一件好事吧。專門囑咐我,要關注你的情況。

Geng Xiaonan: Your interview really was a gift both to me and to Professor Xu, and I’m indebted to you. As you know, over the years the professor was never one of those scholars who produced easily accessible work or whose writings appealed to the general reader, unlike, say Professor He Weifang, or people who are not scholars, like Ren Zhiqiang. These gentlemen have addressed issues in a far more popular style. Mr Xu, however, focussed on writing for decades and he’s published some thirteen books and four translated volumes. On average, that’s a book a year.

He really is one of those ivory-tower scholars devoted to his research whose writing style is beyond the grasp of many. As a result, his circle of ‘fans’ is pretty much limited to the intellectual elite. In other words, he’s not a populariser or someone who panders to the public. As a result, when these troubles befell him [starting in August 2018] there’s been far less awareness or public attention paid to his situation relative to other endangered scholars. But then, he has quite an international reputation as the preeminent Chinese legal scholar. So, on balance, things haven’t been too disastrous; it’s his international reputation that has come to his rescue. Indeed, the response to the news of his persecution has been much greater internationally than in China. For the moment he’s survived [this is a reference to his detention and release in early July]. That’s why I’m particularly grateful to you for your interview. It introduced people to Mr Xu’s work. Since I don’t express myself in a particularly highfalutin way, that interview allowed your listeners — everyday people — to glean some sense of Mr Xu and what he does.

耿瀟男:姐姐,就是這次訪談真的是姐姐送給我以及送給那位大先生的一個大的禮物,瀟男心裡非常非常的感激、感恩。嗯,那位大先生說實話,這麼多年,他不是那種普及型的學者,他不像賀衛方教授,不像別的比方說任志強,這樣的人士他們的言論基本上是大眾普及類的,而許先生這麼多年,二十年內光是寫作,他十三本著作,大概是四本譯著(出版),幾乎是一年多一點點就是一本書。他真的是象牙塔里面潛心治學的那種學者。而且他的寫作,姐姐你也看到了,他的文風真的是有門檻的,所以能夠讀懂他的文章的人,並不是像能夠讀懂其他學者那種(人那麼多),所以他的粉絲,就是精英層裡面的。所以他一點都不大眾,一點都不親民。所以這也致使他,他出事兒,可能這種關注在大眾層面,中國大陸大眾層面的關注度,比別的普及的學者要少得多。但是因以為這麼多年他的國際影響力,在中國法學界裡面是第一的。所以說還好,完全靠他這麼多年的國際影響力,所以說他出事兒呢,海外的反應比國內的反應大多了。這次終於就是算暫時的度過了。所以說姐姐,這樣子回頭看,您的這次的這個節目啊姐姐,我真的心裡面非常感恩。這個節目在大眾層面,給了許先生一個——因為我的語言嘛也沒有什麼可高深的,所以您對我的這個訪談,在大眾層面給了許先生一個推廣和普及。我自己是這麼看的,所以非常非常的感激。

Bei Ming: You’re right. It seems that our exchange resonated among listeners and the reverberations have continued. But, I must say that, as has been the case with other popular programs that I’ve done, as soon as the number of hits goes up [that is, there has been an increased number of listeners] those ‘Fifty-cent Trolls’ get in on the act and do their best to confound things. It’s become something of a pattern. No one will troll you if what you’re doing has no impact, but as soon as you do — say when you get tens of thousands of hits — then they’re on the case. ‘Fifty-centers’ started popping up shortly after the first part of our conversation was broadcast. But, regardless of that, people are paying attention and we know that because they have been posting comments expressing concern about your safety and wellbeing.

北明:你說的是,這個節目最近好像還在發酵,而且好像發酵的速度越來越快。而且我發現了,就跟我過去做的一些訪談節目一樣,只要點擊率一上去,五毛的跟帖就開始出現,灌水的就開始來了。這是一個規律。你如果沒有影響,五毛他們也不出現,你稍微有一點影響,比方說點擊率上萬了,那個就來了。你這個(訪談)也一樣,上集現在已經開始有五毛出來了,我一看點擊量也上去了。會不斷發酵,底下跟帖也在關注你的安危情況了。

Geng Xiaonan: Of course, I understand, but none of that scares me — none of the negative postings, the insults or nasty responses matter. That doesn’t worry me at all; it’s evidence that our discussion is having an impact and that’s a good thing, despite the fact that it elicits that kind of stuff. Far worse is silence; that is, if people simply don’t listen or pay attention. Forget the bouquets and brickbats — it’s silence that scares me. Like Mr Xu, I feel that when all of that happened [when he was detained in early July], it didn’t matter that they spread lots of fake news and ridiculous stories internationally, including claims that Xu had solicited prostitutes. [Note: Here Geng uses the expression 藍金黃 lán jīn huáng, literally ‘blue-gold-yellow’. 蓝 lán signifies the efforts of the Chinese internet police (who wear blue uniforms) to censor online information; 金 jīn refers to the use of bribery to control individuals; and, 黄 huáng indicates honeypot ploys employed to ensnare victims.]

Just think about it, my profession [as a publisher and film producer] is about providing content; you could say that I’m in the media, and so I’m aware of my situation and completely mentally prepared [for what the authorities could get up to]. Rest assured. When a program like ours has an impact, even when half of the responses are negative, when you get the same number of brickbats for all the bouquets, or even when two thirds of the responses are negative, it doesn’t matter. That’s because we have already achieved our aim of getting word out about heroes [like Xu Zhangrun], not only about who they are and what they’ve done, but about what they have said and what they stand for.

耿瀟男:姐姐,姐姐,關於五毛們跟帖,有很多負面的這些辱罵呀或者各種反饋,這些不怕,不怕姐姐,絕對不怕。這就說明節目的影響出來了。正因為節目的影響出來了,才會有這些,這些東西也跳出來了。所以說,這是好事,這是好事。最壞的事就是說默默無聞,誰都不關注,無論鮮花也沒有,板兒磚也沒有,這是最壞的。所以說我們不怕。包括許先生出來這個事兒出來以後,海外的這些假的、被「藍金黃」了的這些,也有很多說他就是嫖娼了的,這些都沒關係。姐姐你想啊,就算是我的職業,一直就是所謂的內容提供商嘛,所以說也算半拉傳媒,這方面我是有充分的思想準備以及有充分的認知的,您放心。一個節目的影響力出來了,哪怕就是百分之五十對百分之五十,鮮花兒和版兒磚是百分之五十對百分之五十,都是很好很好的事了。甚至板磚拍的是三分之二,鮮花兒只有三分之一,那其實也說明咱們把這些英雄們他們的人,他們的事,他們的言論,他們的思想我們已經傳播了,我們已經達到目的了。所以說不怕,不怕姐姐。

***

Bei Ming (addressing the audience): In everyday life people of conscience all too easily fall back on a belief that ‘in the end, the public will always know the truth’. In reality, ‘public opinion’ does not necessarily accord either with the facts or with the truth. Einstein, Madam Curie and Mother Teresa were all denigrated and vilified during their lives, just as much as they enjoyed plaudits and affirmation. Or, even more striking is the case of Jesus Christ, a man condemned by his own people who ended up nailed to the cross. In the East, Confucius wandered the land, ignored for fourteen long years, and Socrates, one of the founders of Western philosophy, was condemned to drink hemlock. Or there’s Qu Yuan in the Warring States era, a loyal but disaffected minister who went into exile and eventually drowned himself … … The list goes on; it records the names of the heroic figures and people of conscience who struggled for freedom and decency, men and women who, in their quest for the public good, have ended up condemned by ‘public opinion’. Contemporary China seems to specialise in successfully marrying its particular brand of evil politics to willful public ignorance. For seventy years now, the muddled thinking of normal people has been complicit in the elimination of countless heroic figures.

But Geng Xiaonan had another concern, one distinct from that fateful marriage of malevolent power and public ignorance, something that is pressingly relevant:

主持人(北明):現實生活中,人們往往以“是非自有公論”安撫受挫的良心,但是所謂“公論”並不總是接近真理和事實,像愛因斯坦、居里夫人、特麗莎修女這樣偉大的人物在世的時候,都是遭人詬病而毀於參半。再往深看,西方聖賢耶穌是被自己的族人送上十字架的,東方聖賢孔子被迫流亡了十四年,古希臘知識奠基人蘇格拉底被判死刑飲鴆身亡,戰國時代忠君愛國的士大夫屈原被放逐鬱鬱不得志投江而死……。為尋求公義而慘遭“公論“扼殺的民族英雄、人類良知,自由的追求者遍及古今中外,名單可以列出很長。但當代中國的特產是,這樣的邪惡經常聯手愚昧,七十多年的民間愚昧,一起詆毀赤子忠良。

而在這個邪惡加愚昧的淵藪之外,瀟男另有擔憂,並非杞人憂天:

Geng Xiaonan: My greatest fear is that they will do him to death without anyone even hearing about it; that the Communists will let him die in prison.

耿瀟男:我最擔心就是他默默無聞的被整死,被共產黨關死。

***

Bei Ming (addressing the audience): Either you may be exterminated by the regnant powers, unknown and unheard of, yours an ending enveloped in silence. Or, you might achieve such dangerous notoriety that you are belittled, besmirched and befouled by the authorities. In the process, you are stripped of all credibility with the public.

To live in China and to confront its realities you’ll only be able to pursue your belief in truth and justice if you are one of those rare individuals who, profoundly aware of its dark history, and despite it all — the growing pains, the fraught celebrations, the despair and struggles — loves the place passionately. Let us hear what else Geng Xiaonan has to tell us.

主持人(北明):要么寂寂無聞,聽憑權力整肅,無聲無臭的死去,要么赫赫有名,被污化矮化髒化,徹底失去公眾信譽。生於長於歌哭於奮鬥於這樣的土地和現實,如果沒有對故國的痛愛,沒有對歷史、真理和公義的信仰,不可能堅持到最後。我們繼續聆聽耿瀟男的閨房話。

***

Geng Xiaonan: The year 2020 is indeed a crucial time and, although I’m only a minor figure in all of it, I too feel the need to answer the question: What have you contributed? So,I will do whatever I can to offer you my assistance and support. I’ll also undertake whatever ‘homework’ you might assign me. I’m not just talking about Professor Xu Zhangrun. Because of the work I have done over the years organising and participating in various discussion groups, symposiums and seminars, I’ve been in frequent contact with a range of China’s independent public intellectuals, as well as significant artist-activists. They included not only prominent champions of Chinese law and legal reform like the rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang and Professor He Weifang [of Peking University], but also many other engaged public intellectuals, both in Beijing and Shanghai. I am happy to help in any way I can regarding contacts and organising things at my end.

As I’ve said, I am particularly aware of the importance of the critical year, 2020, although my more active involvement in things actually dates from 2018 [when Xi Jinping became effectively China’s ‘ruler for life’, resulting in a widespread sense of a looming political crisis]. Moreover, the roots of my hopes for these crucial few years were sparked over ten years ago. It was then [around the lead-up to the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games], that I was more focussed in thinking and working for China in the belief that we would see some significant changes within the decade, by 2018. I thought, surely by then enough will have happened [socially, economically, politically and culturally] for the county to be ready [for significant progressive political change]. China would be on the cusp. It was inevitable. But the years passed and things simply dragged on. I have no idea how long the Chinese people are fated to go on like this. Regardless, that’s why, Dear Ms Bei Ming [Note: This is an affectionate expression that Geng used in her conversations with Bei Ming], I am well equipped to respond readily to any ‘homework’ that you might chose to assign. I’ll undertake it to the very best of my abilities.

耿瀟男:今年真的是關鍵的年。我這個小人物我經常問自己,你交的答卷是什麼?姐姐你那邊只要需要,我這邊隨時地(配合),只要您出作業,我這邊就交作業。不單單針對許教授。這麼多年,因為各種沙龍、論壇,我組織這些活動的關係,跟國內的自由派公共知識分子們,或者公共藝術家們,無論是浦志強他們還是賀(衛方)老師他們,還有北京上海的各個公知們,也都算是頗有交道。姐姐需要哪方面的資訊,或者其他的選題,我能配合的我都配合。

因為我覺得這樣的這個庚子年——我從戊戌年開始,我從早十年前就開始盼、開始盼,那麼到了戊戌年,2018年,總是覺得時間差不多了,夠了!快了!必須了!但是一直一直拖。我不知道中國人的這樣宿命還要拖多少年。所以說,在庚子年,姐姐,您那邊願意出什麼作業,我就交什麼作業,只要是在我能力範圍以內的。對,就是這樣的姐姐。

***

Bei Ming (addressing the audience): [The Soviet-era Russian poet] Anna Akhmatova would become known as ‘the pearl’s light of Russian poetry’ following the Great Terror of Joseph Stalin [in contrast to Alexander Pushkin who, when he died, the literary critic Vissarion Belinsky said of him: ‘The sun of Russian poetry has gone down’]. In her singleminded dedication to finding out what had happened to her son [Lev Gumilev, who had been detained] she stood in line outside KGB prison headquarters [in Leningrad] day after day, through sweltering heat and bitter cold, for seventeen long months. One day, a ‘woman with lips blue with cold’ recognized her and quietly asked: ‘Could one ever describe this?’ Akhmatova replied in a whisper: ‘I can’.

Over the three decades of Stalinist rule Akhmatova was able to pass the test that she had set for herself and she did so in ‘Requiem’, a cycle of poems composed and revised from 1935 to 1940 [‘Requiem’ was published in full in the Soviet Union in 1987, until then only a partial version was in circulation. It is the best-known poetical work about the Great Terror. As Akhmatova wrote in the poem,‘my tortured mouth/ Through which one hundred million people scream’.]

Her voice of tragic power decries ‘the locks of a jail, stone, And behind them – the cells, dark and low’. [The famous, yet persecuted composer] Dmitri Shostakovich hailed that epic poem as ‘a memorial for the victims of the Great Terror’. Akhmatova’s poem was finally published in Russia fifty years after she began work on it. Over the years it was circulated in handwritten copies. … [In the recorded version of the exchange, Bei Ming plays Akhmatova: Requiem (1979-80) by the English composer John Tavener, a work which circulated in the Soviet underground during the 1980s.]

During its darkest days, China has had its own ‘Vladimir Highway’ [like the one that infamously connected Moscow to Siberia; that is, from the capital to the gulag]. It is a passage along which ‘the saints hold the hands of the geniuses; martyrs support the shoulders of the poets’. —— No one is standing behind Geng Xiaonan asking: ‘Will you be worthy of answering the challenge of the year 2020?’ But Geng offers a response anyway and in so doing she tells me that she would never forgive herself if she failed to rise to the challenge.

主持人:在苏联恶名昭著的斯大林大清洗年代,阿赫玛托娃,这位被称为“俄罗斯诗歌的月亮”的俄罗斯诗人,为打听被逮捕的亲人的下落,在克格勃门外的酷暑严寒中连续排队十七个月。一天,她被排在自己身后一位“嘴唇毫无血色”的女人认出来了,那女人突然在她的耳边低声问:“您能把这些都写出来吗?”阿赫玛托娃悄声回答说:“能”。此前此后历经三十年,阿赫玛托娃对那个暴政时代交出了自己的答卷:写出了她的组诗《安魂曲》。这是“苦役的洞穴”里的悲声,音乐家肖斯塔科维奇称其为那个“恐怖时代所有受难者的纪念碑”。此詩在蘇聯本土五十年後出版之前,以手抄本形式在地下流傳。… 在黑色的歲月裡,中國也有一條弗拉基米爾大道,在那條道路上,也是「聖徒拉著天才的手,殉道者扶著歌者的肩頭」。——沒有人站在耿瀟男身後這樣問她,你能交出庚子災變之年的答卷嗎?但是耿瀟男告訴北明,如果她不能交出一份像樣的答卷,她不會原諒自己。

Geng Xiaonan: I am grateful to you. I have been worried that I would hand in a ‘blank assignment’ during this crucial year of 2020. We are going through a major historical inflection point. If I were not to act now, I have no doubt that from the vantage point of old age, I wouldn’t be able to forgive myself.

耿潇男:我要感謝姐姐,要不是姐姐,我在庚子差點兒交白卷,不能交白卷。在這樣的一個大的歷史的時刻,不能交白卷。以後到老了,回頭想起來,就會抽自己耳光的。

***

Bei Ming (addressing the audience): Geng Xiaonan’s achievement is not a response to any particular questions or requests made of her. It is entirely of her own. This ‘intimate exchange’ between two close female friends is for me a profound reminder of the importance of people like Geng Xiaonan during an era of national despair of the kind China is presently experiencing.

In an age of unforgiving harshness, such intense and passionate dedication is like a dissolvent, it opens up a vista of possibility beyond the barren landscape that confronts and threatens to confound us.

主持人:這張答卷,當然不是北明對她的採訪交出的,而是她自己的行為成就的。而這樣的閨房話,是這個民族沈淪中的救贖之音,是這個冰冷的水泥時代最繾綣的溫情,是這片文化荒蠻之地上一道綠色的風景。

***

Source:

***

***

I have so many things to do today.

I must slaughter memory to the end,

I need for my soul to turn to stone,

I must once again relearn to live.

— from Anna Akhmatova, ‘Requiem’

trans. by Alex Cigale