Watching China Watching (IX)

Stephen FitzGerald, more than many Australians involved with China over the years, is particularly aware of the unsteady history of Australia’s dealings with Asia since the nineteenth century. In his memoir, Comrade Ambassador, the story of a life and the history of an era, he speaks with unsettling clarity about what he calls Australia’s ‘litany of discoveries of Asia’, as well as recording his repeated personal efforts through diplomacy, education, policy advice and business engagement to broaden the Australian mind as it has contemplated what was once called the ‘Near North’.

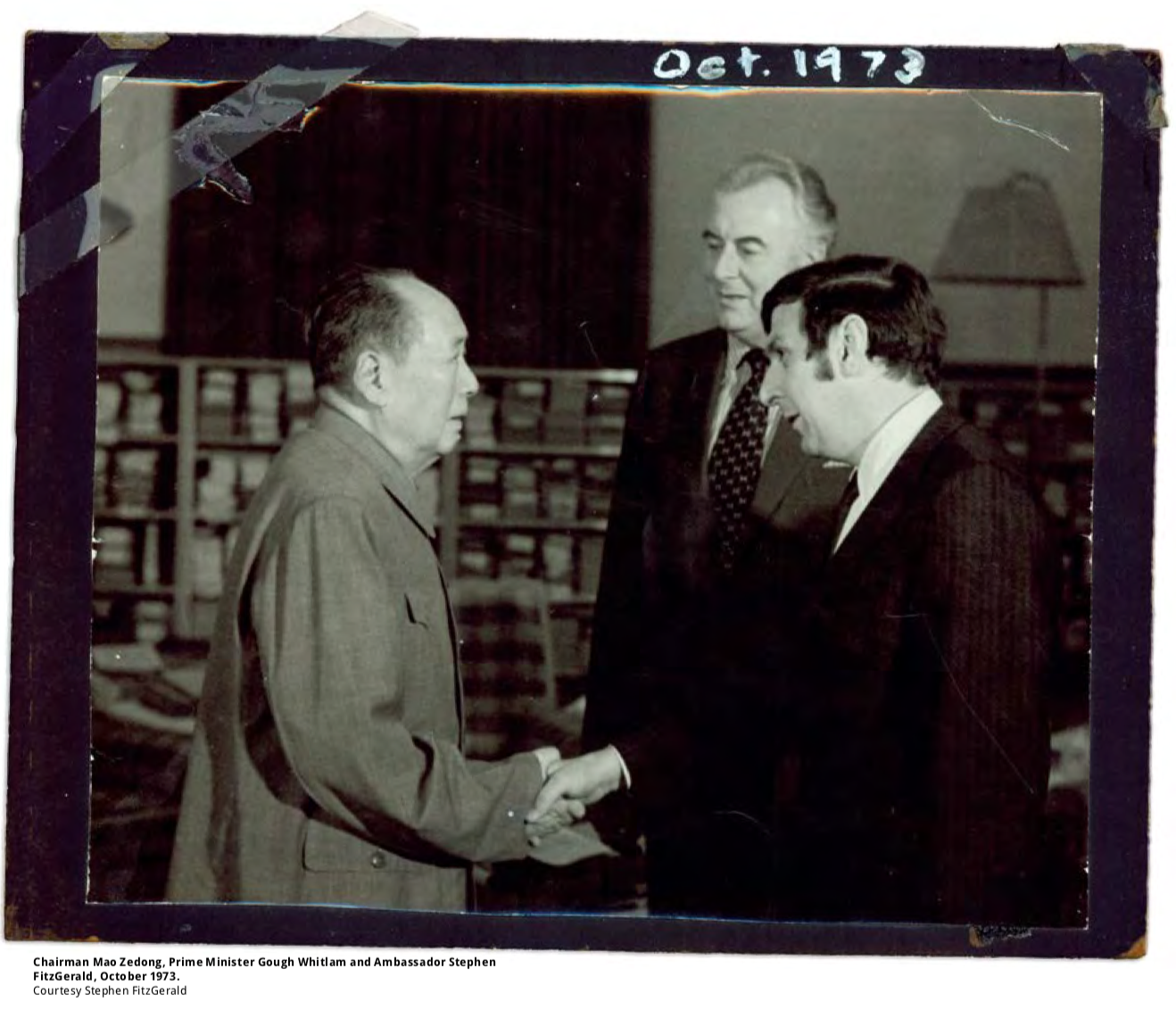

With his appointment by Prime Minister Gough Whitlam as Australia’s ambassador to the People’s Republic of China in 1973, Steve would spearhead another age of discovery. However, as he notes soberly in Comrade Ambassador:

I had a whole collection of books by or about Australians in China, mined from the shelves and catalogues of second-hand booksellers. I was conscious of this history, that we had to re-connect it with the present China, that I was not the first anything from Australia in China, not even first diplomatic envoy or first ambassador, for there’d been an Australian diplomatic mission in Chungking from 1941, headed by Sir Frederic Eggleston as minister, then Professor Douglas Copland in Chungking and Nanking, and finally Keith Officer, as ambassador, from 1948 until the communist victory in late 1949.[1]

During his time in Beijing, Stephen FitzGerald would also learn that, like his predecessors in the 1940s, diplomatic despatches sent back to the Department of Foreign Affairs in Canberra might often lie around, launguishing for attention, or end up being pointedly ignored. Sometimes, fortunately, they were taken seriously.

This is hardly a new story. Indeed, as William Sima notes inChina & ANU — Diplomats, Adventurers, Scholars, featured in Watching China Watching (VI), Australia’s first diplomat to China, Frederic Eggleston, was himself disillusioned with the lackadaisical response to his despatches from the wartime Chinese capital of Chungking (today’s Chongqing).

As Sima notes:

On one frosty morning in January 1943 he [Eggelston] confided to his diary that: ‘like children in the marketplace, I pipe unto you and you do not sing. Is it right for me to waste my sweetness on the desert air, in the vacant spaces of Australian minds.’ He would later advise Douglas Copland, Australia’s second minister to China, that: ‘there is no doubt that you can do exceedingly valuable work for Australia in China … [but] you will always have to insist on attention being given to your reports and advice. Otherwise, they will be ignored, pigeonholed or left in the kitchen piano.'[2]

Below we reproduce with the author’s kind permission material from four despatches that Steven FitzGerald composed with Australian embassy staff in Beijing in mid 1976. It was a crucial moment in modern Chinese history, and one of profound significance for China’s engagement with the world.

The despatches were written for a new prime minister, Malcolm Fraser, and his foreign minister, Andrew Peacock, on the eve of their official visit to the People’s Republic shortly after the April 1976 purge of Deng Xiaoping and not long before the death, in September that year, of Mao Zedong and the coup d’état the following month against Mao’s political supporters. Although these despatches were not ‘left in the kitchen piano’, they were, as Steve notes, hardly greeted with unalloyed delight in Canberra.

Through his work in academia (Steve studied Chinese at ANU and, following his ambassadorship to China, for a time headed the university’s Contemporary China Centre), his public service and through his personal example, Stephen FitzGerald was one of the inspirations of my 2005 manifesto On New Sinology.

In his memoir, Steve acknowledges the special atmosphere he encountered at ANU, when he took up the study of Chinese; it is an atmosphere that would suffuse also the years of my own induction into the Chinese world at ANU (1972-1974). As the observations on China Watching by Pierre Ryckmans (Simon Leys) and Lo Hui-min 駱惠敏, who also worked at ANU, Steve is worth quoting here:

I have a gentle and civilised entrée to it [that is, the study of Chinese], in the Chinese department in a converted army hut at the ANU, with fewer than a dozen students and an enthusiastic and happy teaching staff… . Bursts of laughter float along the corridor from their offices. They’re first-class teachers, and the relaxed and happy relations they have with each other and with students, and the intimacy of the small class, make this the most conducive learning environment I’ve ever experienced. I look forward to these hours at the ANU. Any uncertainty about learning Chinese dissipates and fascination and pleasure take over. Here are teachers deeply literate in the language and culture, and they encourage and coax us towards a literacy of our own. It’s another opening of the mind, a joyful experience I’d wish on anyone.[3]

In 2015, as founder of the Australian Centre on China in the World, and editor of The China Story website, I introduced readers to Comrade Ambassador, and provided a link to Stretch of the Imagination, a speech written for us in 2012. I also offered some observations of my own, Seventy Years On & Australia’s Unfinished Twentieth Century. Following excerpts from Comrade Ambassador relevant to our ongoing discussion of Watching China Watching I append the text of the speech I made to launch Comrade Ambassador on the 18th of September 2015.

***

On 16 March 2017, Stephen FitzGerald presented the an oration in honor of Prime Minister Gough Whitlam titled Managing Ourselves in a Chinese World: Australian Foreign Policy in an Age of Disruption, the video of that speech, as well as the full text, can be seen here. In that speech, FitzGerald outlined challenges facing Australia as it deals with the incumbent US president and onward march of the People’s Republic of China. In conclusion, he offers a series of recommendations to the Australian government. Daresay, these will share the fate of similar heartfelt advice to ‘be ignored, pigeonholed or left in the kitchen piano’.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

21 January 2018

China 1976: An Ambassador’s Advice

Stephen FitzGerald

How do you brief them [Fraser and Peacock]? How do you assist them to think about relations with China when you can’t even see the politics now or the other side of the watershed of Mao’s demise? One thing is to give them broader and longer context, which we’re doing in the think pieces we’ve been preparing. We work on them together, but they reflect my distillation of where we’ve got to with China over the three years I’ve been here, and what I think we’ve got to do over the next twenty to twenty-five. In the first two weeks of May [1976] four formal despatches go to [Foreign Minister] Peacock, on poliitcal, economic and cultural relations and, to address [Prime Minister] Fraser’s concerns about the Soviet Union, one on Sino-Soviet relations. …

On Politics

The first, ‘Political Relations with China: Are they too hard?’ addresses the China-sceptics. I write that no matter how hard it might seem working with China, Australia can’t walk away. After Mao dies China will rapidly pull out of the political mess it’s in and abandon Maoist fundamentalism for a position more attuned to the real problems of governing, and more reform-oriented strategic development, and this will make China a very different proposition for us. Historically, China has been the predominant political and cultural force in this region, and the ‘further extension of its power and influence will be an increasingly dominant factor in our political environment in the latter part of this century’. Given close involvement with the region is a constant for Australia, this means we have to work out how to accommodate to Chinese influence, and it provides a clear and basic justification for making the effort. To live within the orbit of Chinese influence requires a cultural leap on our part, to enable us both to live with and benefit from a predominant China and to protect our national interests and identity. We have to know China so well we’ll be able to discern when apparent benign Chinese influence might conceal intentions ultimately harmful to Australia. This also requires a long-term view of political developments across the region and a leap in our capacity to know our other Asian neighbours. The fundamental task now in our political relations is to institute a massive broadening in our approach, including in our own education, from primary school on, so we can develop an Australian community culturally adjusted to the fact of this China and a bureaucracy that can more adequately manage our adjustment.

Will the Chinese meet us half or even part way? That’s the challenge Fraser and Peacock face. I urge them to take the Chinese on, pressure them to engage, to have greater political communication. In the forthcoming visit, ‘There will be an opportunity both to press and provoke, and to begin the process of achieving greater understanding of what the Chinese are about.’ Their language isn’t always easy, but we have to accept it as the expression of thinking of this power that seems set to become dominant in the region, and try to understand it. To simply dismiss it is dangerous.

Convention requires a ministerial response to formal despatches, but the department, which has responsibility for collecting views and drafting the reply, does not acknowledge it. As the title of our despatch implied, it must be ‘too hard’.

On Economics

The despatch on economic relations also says we have to get mentally past what’s happening now and imagine the future, that if the Chinese economy, and China’s trade with Australia, were to expand in the last quarter of the twentieth century in the way the Japanese economy and trade with Australia did in the third, by the year 2000 China would have a dominant role in the expansion of the Australian economy. We write that if we can accept China’s own growth strategy as realistic, this would mean an annual growth in the vicinity of 10 per cent over a period of twenty-five years, leading to a ten-fold increase in GDP in real terms by the close of the century. Our projections assume stability in politics and commitment to economic reform, but most of all that China will rediscover for itself the dynamism we’ve seen in other Asian societies that have their roots in Chinese culture. China will still have to make ideological and institutional adjustments but this is essentially what Chinese politics is about now, and I suspect, however much pain it causes, the answer will be one that takes China away from dogmatic self-reliance and Marxist-Leninist purity towards greater economic flexibility. In so doing, the Chinese will look for inspiration both outwards towards the world for ideas, and inwards, to ideas inherent in traditional Chinese culture and society and qualities inherent in the Chinese people. The result, if successful, could mean a capacity to respond to the requirements of modern economic and technological development that might rival that of Japan.

This despatch is also met with official silence, but the loud guffaws of incredulity in Canberra can almost be heard from Beijing.

On Culture

The despatch on cultural relations brings up the really hard part. China isn’t a habit of mind for Australians, I write. The influence it wielded in its own universe for two thousand years before the Europeans arrived is unknown. The traditional culture and the political and social concepts that influence the China we deal with are uncomprehended. The historical spread of Chinese influence is a process we don’t understand. There’s intrinsic worth in understanding Chinese culture for its own value, but the purpose of this despatch is to suggest there’s a national interest in the promotion of culture, including scholarly and research exchange. Without this, our relations with China will never be more than superficial, and we’ll be damagingly ill equipped to adjust to a China dominant in our region.

My recommendation is not for an instrumentalist add-on but for grounding the whole relationship in cultural understanding and exchange, to enrich our own culture, to comprehend Chinese society and other Asian societies influenced by Chinese culture, and to remove the profound lack of understanding that stands between us and a more fruitful political relationship. I recommend funding for cultural exchanges be separated from Foreign Affairs cultural relations vote, and that we proceed now to establish a government-funded Australia-China foundation. We subtitle the despatch, ‘A case for the disproportionate effort’.

This despatch is the only one that gets an answer. In early June, I receive an intemperate letter from Renouf, which attempts to rebut everything I said, takes a swipe at the Australia Council’s CEO Jean Battersby for allegedly bypassing the department to pursue her own cultural relations policy and ends:

the burden of your argument hinges on the belief that the next 25 years will see the extension of a dominant Chinese power and influence throughout the region. Possibly you will be proved correct but your logic does not persuade me … .

Jocelyn Chey, Cultural Counsellor, Sinologist, intellectual, wit, musical talent, mainstay in scores of lunches and dinners nudging open the cultural and scientific and educational relationship, and main author with me of this despatch, threatens to resign in disgust.

On Sino-Soviet Relations

Our despatch on China-USSR relations, although not written with that intent, also gets up the nose of the department, which believes the split between China and Russia is temporary and that when Mao dies relations will revert to where they were before. They fear Soviet expansion but say it’s too strong for us to oppose, and they see China and the USSR acting in concert against our interests. Their policy is to be even-handed betweeen the two. My judgement is that reconciliation with the Soviet Union is contrary to everything we know of the Chinese view of their history, their attitude to Soviet foreign policy, and their resolute opposition to Moscow’s policy of subordinating the sovereignty of other communist powers to the interests of the Soviet state. Whoever takes over after Mao will have the same opinion. And if we believe what we say about Soviet expansionism, we should oppose it not temporise.

… The department does not acknowledge this despatch.[4]

Biographical Note:

Stephen FitzGerald began his professional career as a diplomat, studied Chinese and became a career China specialist. He was China adviser to Gough Whitlam, and Australia’s first ambassador to the People’s Republic of China, and in 1980 established the first private consultancy for Australians dealing with China, which he continues to run. Since the late 1960s, he has worked for policy reform in Australia’s relations with Asia, and for Asian Literacy for Australians. He chaired the 1980s committee of the Asian Studies Association of Australia on Asian Studies and Languages in Australian Education, and the government’s Asian Studies Council, which wrote a government strategy for the study of Asia in schools and universities. In the same year, he chaired the government’s Committee to Advise on Australia’s Immigration Policies, which wrote the landmark report, Immigration. A Commitment to Australia.

He was head of the ANU’s Department of Far Eastern History and also of its Contemporary China Centre in the 1970s. In 1990 he founded and until 2005 chaired

the UNSW’s Asia-Australia Institute, dedicated to making Australia part of the Asian region through think-tank activities and ideas-generation by regional leaders meeting in informal discussion. He has been consultant to the Queensland and Northern Territory governments on the introduction of Asian languages to the school curriculum, consultant to Monash, Melbourne and Griffith universities on mainstreaming Asia in university studies, Chair of the Griffith Asia Institute, and Research Strategy Director of UTS’s China Research Centre.

***

Source:

Notes:

[1] From Stephen FitzGerald, Comrade Ambassador: Whitlam’s China Envoy, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 2015, p.97.

[2] William Sima, China & ANU — Diplomats, Adventurers, Scholars, ANU: Australian Centre on China in the World and ANU Press, 2015, p.42.

[3] From FitzGerald, Comrade Ambassador, p.24.

[4] This material is quoted from FitzGerald, Comrade Ambassador, pp.138-142.

Further Reading:

- John Fitzgerald, Australia–China relations 1976: looking forward, Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, 2 November 2007, an analysis of archival material

Living Beyond the Past

Geremie R Barmé

18 September 2015

launching Stephen FitzGerald’s Comrade Ambassador in Canberra

Ladies and Gentlemen:

I too acknowledge the Ngunnawal people, the traditional owners and custodians of the land on which we meet. And I also acknowledge and celebrate our custodianship of this place; I do so in particular since this year, 2015, marks a decade since the animating forces that led to the creation of the Australian Centre on China in the World took more concrete form.

But before I say more about that, I must also acknowledge, with ill-concealed, no, absolutely raw and unconcealed delight and celebration that this week marks the return of our home, Australia, to the twenty-first century. We rejoin a time-line that promises a future rather than an endless loop of backward looking boredom. This week dawned, albeit in a melée of political desperation, ego and crude calculation that followed in the wake of two benighted years of national stewardship under that shameful recidivist, the former prime minister (and never has this combination of words been so pleasing to the ear), Anthony John ‘Tony’ Abbott. This knuckle-dragger was a man who tried to remake the country to suit his miniature vision, to imprison us in a fearful world in which we denied ourselves, our region and our future. It is this narrowness of the Australian mind of the 1950s and 1960s about which, and against which, Stephen FitzGerald writes with such passion in his memoir Comrade Ambassador. It is also the insular world of ‘Asia scepticism’ about which Steve speaks in terms of derision, despair and disbelief. It is a world against which he has rebelled, and led others to rebel for over half a century.

The appearance of Comrade Ambassador is timely in another way, for it is high time we reflected on nearly twenty years of Australia’s craven Asia boom and the desperate long years of lip-service and combined Liberal-Labor Asia neglect. Many passages in Comrade Ambassador — this engaging, funny and in turns uplifting and down-casting — deal with a China that has struggled long and hard with ideological blindness, spent painful years fitfully cauterising swathes of the Maoist canker and embarked with immense difficulty on renewing that nation’s body politic and the Chinese economy.

Steve’s memoir gives us pause, for our part we must now wonder if either of our political parties could manage a similar Herculean task to that of the Chinese since the 1970s, a task which we too must surely face in Australia if not now then in the not-too-distant future. Can the ruling Liberals now realise that the Howard-era formula of radical and soulless neoliberalism married to xenophobia and cultural nationalism has or should really have a limited appeal today. Can they face the fact that this country may have actually grown out of them, or at least far beyond their faux Tea Party rump? That there is ‘another Australia’, one about which over these long months of national prime ministerial embarrassment they have shown themselves to be ignorant of and blind to? And, as for the parliamentary Labor Party, can they dig deep and find for themselves a soul, a voice and a vision? Or are they the party of hidden shallows? Okay, Big Daddy Xi, that is the Chairman of Everything Xi Jinping, in China clutches onto the flotsam and jetsam of Maoism; what’s our excuse here in Australia for cleaving to political bankruptcy?

We are standing in a place [the Auditorium of the Australian Centre on China in the World] that in terms of its immediate past began its gestation a decade ago, in 2005. It was in that year that I was awarded an Australian Research Council Federation Fellowship (I would note with a touch of glee that this honour was bestowed upon me in the same round of awards as that of our new vice-chancellor, the astronomer Brian Schmidt). But, I only had the courage to apply for that major fellowship [one that supported an independent research agenda and provided jobs for other researchers] at the urging and with the encouragement of a dear and treasured friend: the anthropologist Mandy Thomas. Mandy, who is a Vietnam specialist, had worked in the Research Council and she was at the time the pro-vice chancellor in charge of research at this university. Tonight is the first time that I’ve been able to acknowledge Mandy’s support here in this building, one that in part exists because of her crucial encouragement. It’s that support that emboldened me also to establish the e-journal China Heritage Quarterly and to write, in May 2005, the manifesto that launched that publication: On New Sinology. That essay would form the rationale and intellectual underpinning of this Centre.

I’d also like to take this opportunity to acknowledge that we are only some metres away from the old Faculty of Asian Studies building where from 1972 to 1974 I was taught Chinese (along with history, Chinese and Indian, Sanskrit, Prakrit, calligraphy, poetry, Maoism, a smattering of Tibetan, and so many other things). And I further acknowledge a previous ANU student of Chinese studies, a man who had left the university a few years earlier and who was, during my undergraduate studies, working in Beijing: Stephen FitzGerald.

Steve’s studies here were not undertaken in such a grand building as the Faculty of Asian Studies (long ago occupied by the university’s law faculty). In Comrade Ambassador he recalls that he had:

… a gentle and civilised entrée to it [that is, Chinese], in the Chinese department in a converted army hut at the ANU, with fewer than a dozen students and an enthusiastic and happy teaching staff… . Bursts of laughter float along the corridor from their offices. They’re first-class teachers, and the relaxed and happy relations they have with each other and with students, and the intimacy of the small class, make this the most conducive learning environment I’ve ever experienced. I look forward to these hours at the ANU. Any uncertainty about learning Chinese dissipates and fascination and pleasure take over. Here are teachers deeply literate in the language and culture, and they encourage and coax us towards a literacy of our own. It’s another opening of the mind, a joyful experience I’d wish on anyone.

It was that department and its teachers, my own beloved tutor Vieta Dyer (Svetlana Rimsky-Korsakoff) — and she is here tonight — who taught Steve in the late 1950s, and worked tirelessly (and sometimes pitilessly) to ensure I acquired her crisp Northern Chinese accent and unfailing correct tones. (When she was visiting the Centre the other day to see our exhibition China & ANU, she reminded me that she still hasn’t quite forgiven me for spending a few years in Shenyang in the 1970s and, for a time, polluting my pellucid Beijing accent so painstakingly acquired from her with a North-eastern drawl, one that still freights itself into my speech when I’m A) tired or, B) drunk, oh, and speaking Chinese. Steve would think my accent was cute, and I remember him taking the piss out of me when we were all camped out around the Embassy pool following the 1976 Tangshan Earthquake, when for a time Beijing became a tent city.)

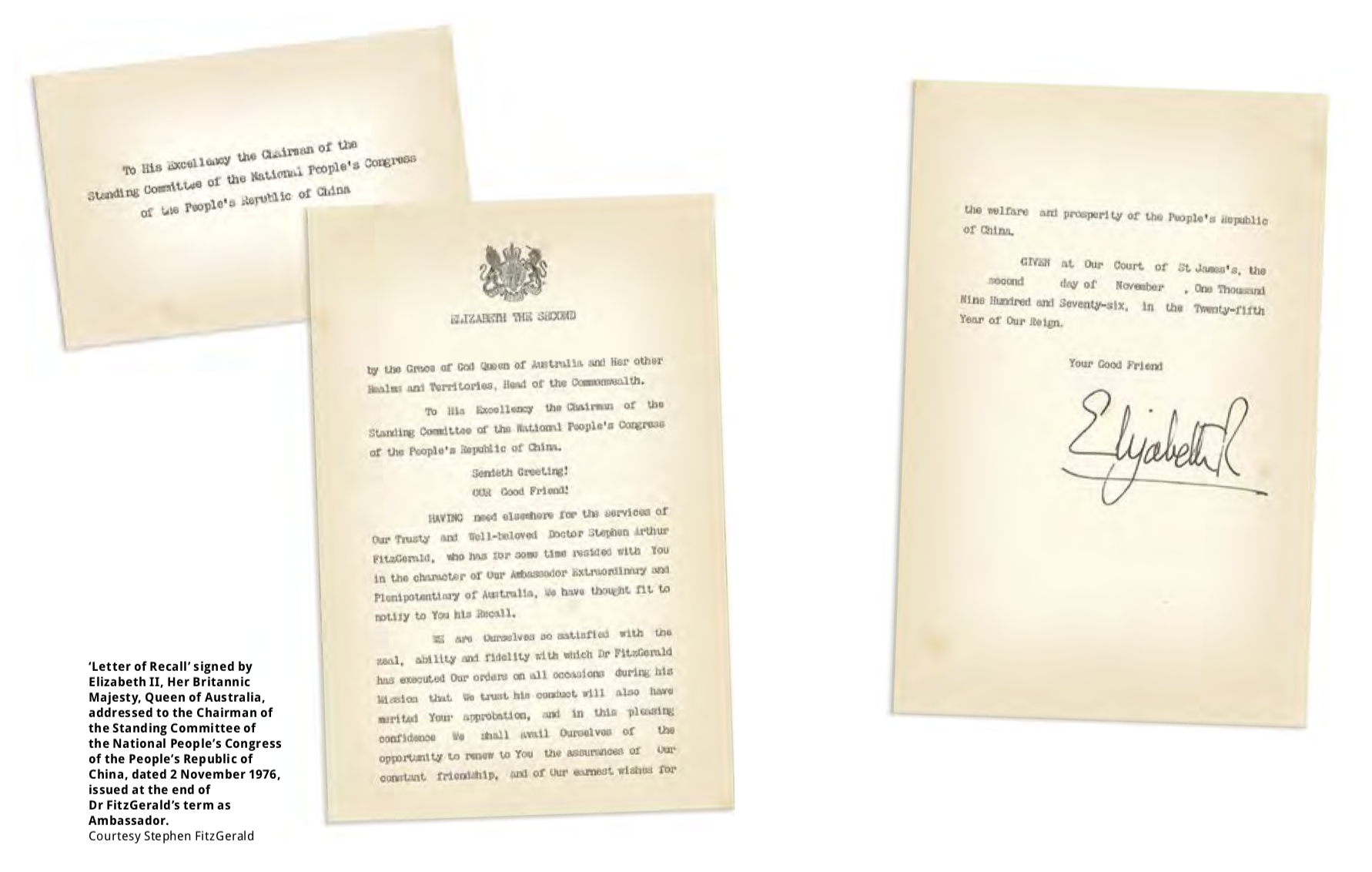

But when I was an undergraduate here, where was Steve? We’d seen him in the news, appointed as ambassador to the mysterious city of Beijing — the Pyongyang of its day — and, more so, that he was there to act as Her Majesty’s Ambassador to the People’s Republic of China. Writing in the well-worn and formulaic prose of the Court of King James in the Letter of Recall in 1976, the British monarch, our Queen, would describe Dr Stephen Arthur FitzGerald as her ‘Trusty and Well-beloved’ acting in the character of Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of Australia. He was residing in Beijing on behalf of Her Royal Highness Elizabeth Regina, Queen of Australia and her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth.

As a callow youth I did not yet realise that Steve would join my other ANU mentors and, like key figures in my intellectual and China life, including Pierre Ryckmans (known to many of you as Simon Leys, the one-year anniversary whose passing in August 2014 we marked here in the Centre only last month), Liu Ts’un-yan, Lo Hui-min and Wang Gungwu, be someone who influenced the ideas that led to the creation of this Centre and therefore helped provide the hall in which we are this evening.

It’s forty-one years ago, give or take two weeks, since the second group of Australian exchange students sent to study in the People’s Republic of China following the normalisation of bilateral relations in late 1972 walked into the office of the Australian Ambassador. Steve, wearing the de rigueur light coloured — was it baby blue, beige or coffee-coloured, Steve? — Safari Suit (the Aussie equivalent of the Mao jacket), his black locks a near leonine mane, and with a manner that was immediately affable and intimate. The five of us sat around and he perched himself on his office desk and introduced us to our new lives, and to the aspirations of a young embassy and an Australia seriously intent on its involvement with China.

Steve, and the staff of the embassy in the 1970s, some of whom are here tonight, embodied something that profoundly influenced us: serious engagement with the place they were in; an excitement about their adventure, about really embarking on a new stage in Australia’s understanding of China, a country this nation has grappled with since the nineteenth century; a raffish sense of humour; self-deprecating appreciation of the absurdity of Maoist China and, a readiness to listen to us! It was amazing: I was only twenty and had all the self-important arrogance of a youth who had but a smattering of knowledge. Over the years that I was a student in China (first in Beijing, then Shanghai, followed by gulag Shenyang), embassy staff, and I think in particular of Steve, Murray McClean, Jocelyn Chey, Ross Maddock, David Ambrose and Reg Little, were never condescending, always interested (okay, they were also collecting intelligence from kids like me who were having a different and direct China experience in universities) and light of touch in their support for and interest in us.

They would offer us meals and advice, social relief from the relentless boredom of regimented student life, escape from the droning politics of dying Maoism and its ridiculous mass campaigns (which fascinated me). Later, when I lived in the provinces, they would be a lifeline of sanity and succour. Jocelyn in particular would make it possible for me to visit Beijing, each trip involving a convoluted bureaucratic rigmarole that Jocelyn would sweep aside in her best ‘She Who Must Be Obeyed’ tones telling the Chinese educational authorities that ‘Mr Barmé’s presence is required in Beijing’.

Of course, Steve and students of China like myself work on a country and civilisation that in so many ways and in many areas has stolen a march on humanity. And China, the longest surviving bureaucratic state in world history, has much to teach us.

It must have been some time in late 1976, about a year before I took early graduation from my dungeon university in Shenyang, northeast China, that Steve invited a group of as to a meal at Tongheju 同和居 at Xidan. This ‘Residence of Community and Harmony’, was one of the more venerable and, for the time, tony establishments in still-revolutionary Beijing. The restaurant had been around since the 1820s but, like everything in China’s Maozeit it was less than even a pale shadow of its former self. For someone like me suffering from anaemia as a result of a poor diet, Tongheju in what seemed like a cosmopolitan city, Beijing, was nothing less than dining paradise.

We finished off our meal with my then favourite dessert, ‘San Buzhan’ 三不沾 (the Three Not Stickies): an imperial era confection made out of egg yolk, mung bean powder and sugar. Globulous on the plate and Day-Glo yellow, San Buzhan got its name from the fact that it didn’t stick to the plate, didn’t stick to your chopsticks and didn’t choke you 不沾盘, 不沾匙, 不沾牙. Usually the best I could hope for in Shenyang was 油炒面 — flour and sugar fried in lard. For some reason, or maybe it’s just a trick of memory, it may well have been the comic delight of this dish that led Steve to take us on a walk south from Xidan and along Chang’an Avenue towards Tiananmen and the heart of Beijing. Together with us he pondered China’s unfolding fate. For years he had been dealing on a daily basis with the bureaucratic obfuscations, writhen rhetoric and byzantine infighting of Maoist bureaucrats. He speculated as to whether the top-heavy machinery of Communist cadres would simply sink the ship of state, or if another fate awaited the country.

Little did I then know that only months earlier he and his embassy colleagues had speculated at length on in a series of extraordinary despatches to Canberra on what post-Maoist China would look like. The content of these despatches features in Comrade Ambassador and, with Steve’s kind permission, I have published passages from them online today. The despatches were basically upbeat, they foretold tectonic shifts in China’s political and economic life; they predicted growth that over the following decades would also transform Australia and its Asian fate; they also appealed to the power that be in Canberra to make a disproportionate effort in dealing with the often arcane and always obdurate world of Chinese bureaucracy.

In the first of the despatches, titled ‘Political Relations with China: Are they too hard?’, Steve and his colleagues wrote:

After Mao dies China will rapidly pull out of the political mess it’s in and abandon Maoist fundamentalism for a position more attuned to the real problems of governing, and more reform-oriented strategic development, and this will make China a very different proposition for us. Historically, China has been the predominant political and cultural force in this region, and the ‘further extension of its power and influence will be an increasingly dominant factor in our political environment in the latter part of this century’. Given close involvement with the region is a constant for Australia, this means we have to work out how to accommodate to Chinese influence, and it provides a clear and basic justification for making the effort. To live within the orbit of Chinese influence requires a cultural leap on our part, to enable us both to live with and benefit from a predominant China and to protect our national interests and identity. We have to know China so well we’ll be able to discern when apparent benign Chinese influence might conceal intentions ultimately harmful to Australia. …

As he also recalls,

Convention requires a ministerial response to formal despatches, but the department, which has responsibility for collecting views and drafting the reply, does not acknowledge it. As the title of our despatch implied, it must be ‘too hard’.

None of this, however, prevented Steve’s ruminations on Chang’an Avenue that night. I was twenty-three and soon to start a fledgling career as an editor and translator in Hong Kong, observing at one remove what would be the momentous developments that soon unfold with the advent of what is still called China’s new era of the Open Door and Reform.

Steve would soon return to Canberra from China and, in Comrade Ambassador he records the disheartening encounter here at ANU that he would have with what I dub the Bureaucrocene. In my spoof of the fashionable concept of the Anthropocene — that is the new world-changing age or human-induced all encompassing transformation — the Bureaucrocene or the age of the bureaucrat regnant is our current epoch, one in which intellectual biodiversity is diminishing and university ecosystems around the globe become more similar to one another, thereby shaping human existence itself.

Back at ANU in the late 1970s, Steve found himself both acting head of the Department of Far Eastern History and the head the Contemporary China Centre. He soon realised, and I quote:

The ANU’s changed… . It’s more bureaucratised, and top-heavy. … Academic matters have to be talked upwards through multiple layers of committees. … You have to spend a lot of time negotiating with business managers. … I attend meetings. Sometimes I find myself running, literally, down the corridors in the Coombs building to get to the next.

He admires the faculty of Wang Gungwu, by then head of the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, who features in the exhibition in our gallery, China & ANU — Diplomats, Adventurers, Scholars, to be both an academic manager and a productive academic. He decides to leave the academy and launches a third career in business consultancy, as well as becoming a major public policy advocate for language learning and Australia’s Asian awareness.

It has been a life-long quest for Steve, it is the story told in Comrade Ambassador, and it is an account both uplifting and sobering, one that with unstinting enthusiasm I recommend to you all tonight.

Thank you.

Source:

- Geremie R. Barmé, Welcome, Comrade Ambassador!, 19 September 2015