From July 1941 until October 1949, the Commonwealth of Australia maintained two diplomatic legations in the Republic of China. Frederic Eggleston, then one of Australia’s leading international relations theorists and an advocate who supported closer ties with Asia, was Minister of the first legation, located in the wartime capital of Chungking, until he was recalled in March 1944, and posted thereafter to represent Australia in Washington.

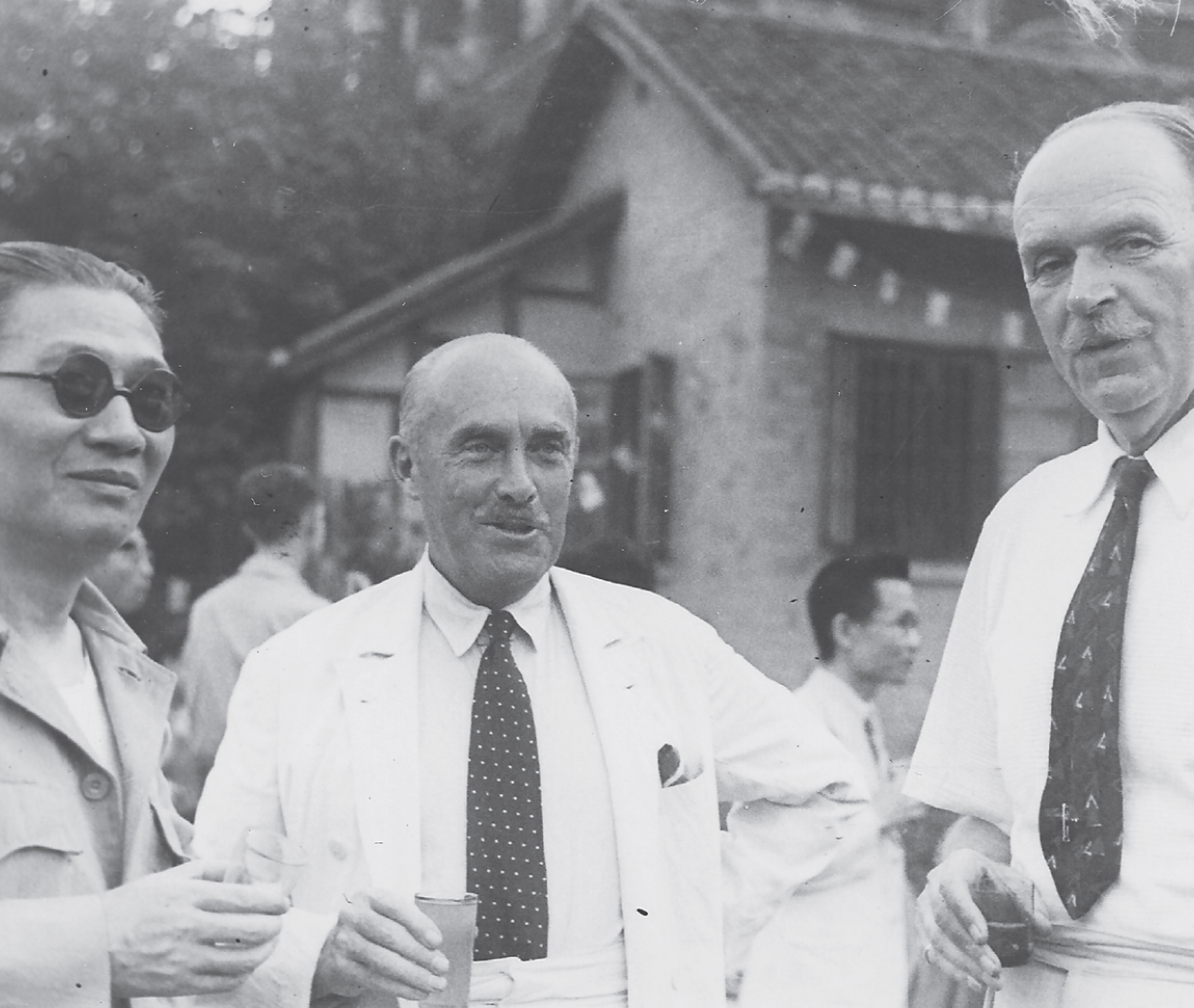

Keith Officer, a decorated veteran of the Gallipoli campaign of the Great War, took over the Chungking Legation as chargé d’affaires until October 1945, when the New Zealand-born economist Douglas Copland was formally appointed as Minister. Copland served in Nanking, the retaken capital of the Republic of China, until April 1948. He returned to Canberra to become the first vice-chancellor of the new Australian National University (ANU).

Keith Officer returned to China in June 1948, this time as Australian ambassador. This more senior diplomatic title went some way to reassuring the Chinese government that Australia treated the relationship seriously — but that would all be irrelevant in less then a year, when Communist forces crossed the Yangtze River and seized Nanking in April 1949. Australia did not recognise the People’s Republic of China until 1972.

The following selections of writing describe the fascinations and foibles of diplomatic life in Nanking during its final four years as Republican China’s capital. The first excerpt, drawn from my 2015 book China & ANU: Diplomats, Adventurers, Scholars, covers the war’s end as witnessed by Keith Officer, and Douglas Copland’s impressions of Nanking during his early months as minister. This is followed by short accounts from the third secretary Barry Hall, from the Legation’s clerk and archivist, Margaret Lundie, and the accountant William Hamilton.

The late 1940s were formative years in the diplomatic history of Australia (a country which had only belatedly established its own independent Ministry of External Affairs, separate from the Foreign Office in London, in 1936). At this time, figures like Eggleston and Copland, whose careers straddled academia, public service and diplomacy in a fashion rarely seen today, could be appointed to such pioneering overseas posts without any prior ‘experience’. Both former diplomats returned to academic life after the war: Eggleston as a lecturer at External Affairs in Canberra, and as a member of the ANU interim planning council from the moment of the university’s founding in August 1946; Copland as the ANU’s first vice-chancellor. Both men were adamant that the study of Asian languages, history, geography and diplomatic affairs should be included in the new Research School of Pacific Studies at the university, and they successful persuaded the council to include these disciplines in the school’s academic structure. In mid-1950, Copland invited the British sinologist C.P. FitzGerald, whom he had first met in Nanking, to head the university’s Department of Far Eastern History. In that role FitzGerald initiated the formidable task of starting an Asian library collection from scratch.

The Chinese Communist revolution and the Korean War swiftly consigned to obscurity this ill-fated, yet intriguing early chapter of Australian diplomatic history; more broadly, the Cold War denied almost all possibility for a nuanced view of China’s Anti-Japanese and Civil War history for decades. Noted American China scholars such as John King Fairbank and Owen Lattimore, both of whom had served in diplomatic roles in China during the war, faced censure under McCarthyism. After a gruelling decade of investigations and senate hearings tarnished his career prospects in the US, in 1962 Lattimore left for Great Britain to become the inaugural Professor of Chinese Studies at The University of Leeds (see Nicholas Loubere, ‘Inside Out: Owen Lattimore on China’). While the politics of anti-Communism were perhaps not quite so toxic in Australia, C.P. FitzGerald was frequently condemned for his public advocacy for Australian recognition of the People’s Republic.

— William Sima, Associate Guest Editor

The Prof

William Sima

On 8 May 1945, Germany surrendered to the Allied Powers. By the middle of that year, US forces had succeeded in ‘island-hopping’ across the Pacific, retaking most of the territories that Japan had occupied during the Pacifc War. From Saipan the US Air Force launched devastating raids on key cities on the Japanese mainland, including Tokyo and Osaka; in July, a combined force of predominantly Chinese, British and US soldiers recaptured Burma. It was still widely anticipated that the fighting on mainland Asia, and in China in particular, would continue well into 1946 — yet it ended abruptly with the dropping of atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, on 6 and 9 August respectively.

Among those surprised at the war’s sudden end was Frank Keith Officer, a Gallipoli veteran who served at the Australian Legation in Chungking as chargé d’affaires for most of the time between Frederic Eggleston’s departure from China in March 1944 and the arrival of his successor two years later. Officer had been chargé in Tokyo when John Latham was the Australian minister to Japan and where, on 8 December 1941, he had received Japan’s formal declaration of war. ‘Having had the somewhat doubtful privilege of seeing the commencement of the war from Tokyo,’ he reflected in his despatch titled ‘Victory in the Pacific Day’, ‘it is particularly interesting to see its end from this, the wartime capital of China.’ It was a scene of jubilation:

Within a few moments, Chungking was in a state of hysteria: shouting singing, parading the streets, and, as on every possible occasion in China, le ing o strings of re crackers. A US Army camp near the Legation appeared to celebrate the occasion by the almost continuous ring of revolver shots — one hoped well into the air, but even then wondered where the spent bullets were falling! When the police guard at our gate commenced to discharge their rifles I felt the fun had gone far enough and should be checked![1]

The war with Japan might have ended, but the long-running civil conflict between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and the Chinese Communist Party led by Mao Tse-tung flared up once more. Following the Sian Incident of December 1936, during which Chiang Kai-shek was kidnapped and forced to agree to an armistice and the establishment of a ‘United Front’ between the two warring Chinese political parties against the Japanese, there had been some vague hope of a lasting accommodation. But, as Eggleston had observed in 1943, ‘the reconciliation at Sian was not in fact genuine’. Like so many others, Eggleston was of the view that Chiang Kai-shek had never forgiven Chou En-lai, the charismatic Communist envoy in Chungking, for the part he played in the incident. Eggleston had no illusions about the future of China under Communism: ‘The communists claim to be democratic but it must be remembered that they are trained in communist principles, and the gospel according to Lenin is one of dictatorship.’[2]

Now, the world watched on hopefully as new attempts to forge peace within China unfolded at breakneck speed. At the end of what was turning out to be a momentous month, Officer sent a despatch to Canberra titled ‘Events During August’. The most important development was Japan’s surrender; the second was ‘the decision of the Communist leader, Mao Tse-tung, to come to Chungking to discuss with the Generalissimo … the possibility of an agreement between the Communists and the Central Government.’[3]

On 28 August, accompanied by the American Ambassador, Patrick Hurley, Mao flew from the Communist base in Yenan to Chungking. Shortly before embarking on the trip, Mao ordered the Party’s guerrilla units to regroup into regiments and to advance on key cities and railway lines in northern and central China. He arrived in Chungking, toasted his nemesis Chiang Kai-shek, who he not seen for twenty years, saluting him as ‘elder brother’, and smiled for the cameras as forty days of negotiations to determine China’s future began. The resulting Double Tenth Agreement of 10 October 1945 pledged that both sides would strive to realise political reconciliation, create a national army under unified command and undertake elections for a National Assembly that would initiate the country’s transition to democracy.

As Australian Minister to the Chinese Republic during the war, Eggleston had been optimistic that the country would emerge as a great Paci c power, one with which Australia would need to engage, cooperate and exchange knowledge. In spite of the best efforts of the US envoy, George Marshall, who arrived in Chungking in December 1945 to broker peace between the Communists and Nationalists and establish a ‘strong, united and democratic China’, Eggleston’s successor would find a country wracked by civil war.

A successor to Eggleston, however, had yet to be appointed. Keith Officer reported to External Affairs in Canberra that the ‘main object of China’s foreign policy is to obtain and hold a position in the Council of the nations out of all proportion to its present capabilities.’ The Nationalist government was ‘intensely sensitive to criticism and to anything reflecting in the slightest degree on its prestige’, and that included the appointment and relative prominence of foreign diplomats in the republican capital. Ever since Frederic Eggleston had been sent to Washington the previous year, Officer had often encountered ‘complaint [about] the non-appointment of a new Minister’.[4]

The department would soon appoint Professor Douglas Copland, one of Australia’s most distinguished economists to the position. The New Zealand-born ‘Prof’, as friends and colleagues called him, had enjoyed a career that straddled academic life — most notably as the first Dean of the University of Melbourne’s Faculty of Commerce — and public service, as an economic policy advisor to the Commonwealth Government. Copland was the special economic advisor to all three of the country’s wartime prime ministers: Robert Menzies, Arthur Fadden and John Curtin. In September 1939, Menzies had invoked emergency powers to appoint Copland Commonwealth Prices Commissioner. By having the authority to fix the prices of certain crucial commodities, Copland frustrated the price gouging and run-away inflation characteristic of other wartime economies. To ensure compliance with the new pricing regime and to prevent profiteering, Copland was given the authority ‘to examine the books of any enterprise, to investigate the rate of gross pro t and, if necessary to fix a new one.’[5] Adelaide’s Advertiser newspaper reported that:

Almost without knowing it [Copland] became in a day one of the most important figures on the home front — an autocrat fixing by decrees not subject to Parliamentary revision the prices of goods reaching an annual turnover of over £100,000,000 a year. … No economist has ever been given such authority in any part of the world. … He is a ‘Prices Czar’ in a complete personal sense.[6]

The death of Prime Minister John Curtin on 5 July 1945, and the end of the war only weeks later, brought an effective end to both of Copland’s appointments. When the economist wrote to inform the new prime minister, Ben Chifley, of his intention to return to academic life in Melbourne, he received in reply a suggestion that he might be willing to go to China on Australia’s behalf. The conditions of this new posting were concluded by mid October and, accompanied by his secretary, Sylvia Brown, and Margaret Lundie, who would serve as the Legation’s clerk and archivist, Copland set sail for Hong Kong from Sydney on 28 January 1946 on a Danish merchant vessel, the Slesvig. After a week’s stopover in the British colony, the party flew to Canton and then on to Chungking, arriving there on 1 March.[7]

The Chinese President Chiang Kai-shek had an informal meeting with the new Australian Minister soon after his arrival, one that Copland described as ‘most cordial’. He reported that the conversation confirmed everything he had heard about the ‘very high place’ Eggleston had occupied in Chungking’s diplomatic circles. During the exchange, Chiang also suggested that Copland might ‘be able to assist in the solution of some of China’s economic problems, which he said were very serious.’[8] And it was not long before the Australian discovered how serious China’s problems were, or that endemic corruption among Chiang’s Nationalist officials was at their core.

At this time, in March 1946, Chungking was bustling with grandees, government officials, military personnel, foreign diplomats and journalists, many of whom had converged on the city to participate in or observe the Political Consultative Conference, convened as a result of the US envoy George Marshall’s efforts at mediation between the Nationalists, the Communists and China’s other minor political parties. For his first three weeks in China Copland was caught up in the whirl of diplomatic socialising afforded by this unprecedented gathering.

He found that Chinese government ministers were ‘as a whole … able’, at least in terms of their formal education and experience in politics, but that ‘it is one of the paradoxes of China that there are so many people of ability and so few who accept the broad civic responsibilities that would be found in a western nation.’[9] He discussed the success of Australia’s wartime economic austerity measures with many of the bureaucrats he encountered, including Weng Wen-hao 翁文灝, Minister for Economic Affairs, Yu Hung-chun 愈鴻鈞, Minister of Finance, Chu Chia-hua 朱家驊, Minister of Education and Wang Chung-hui 王寵惠, a prominent jurist and diplomat who was then Secretary of China’s National Defence Council. He was somewhat taken aback to find that frugality or restraint of any description ‘did not seem to interest the Chinese at all … [they] have no interest in rationing or, as far as I can see, in an equitable distribution of their own food resources.’[10]

By contrast, it was soon a ‘well-worn theme’ in Copland’s exchanges with his Chinese interlocutors that the Nationalist government expected ‘much … from America, both in regard to monetary assistance and the use of technical experts’ (it was hardly surprising that the US Army commander ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell dubbed the Nationalist leader ‘Generalissimo Cash-My-Check’)[11]. Much of the aid was delivered by the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), a body founded by the American President, Franklin Roosevelt, to provide support to countries devastated by the war. Two-thirds of Australia’s commitment to the UNRRA, amounting to some £6,563,000, went directly to China where relief supplies were frequently pilfered or sold. Throughout 1946 and 1947, the Australian press carried reports and photographs of UNRRA ships lying idle in Chinese ports, with one Labor MP telling parliament that: ‘clothes donated by Australian workers, bearing Australian trademarks, were hawked along the [Shanghai] Bund or sold openly in the shops’.[12] Just as Australian public opinion and post-war hopes for China deteriorated, so Copland’s view of China’s Nationalist government rapidly turned from cautious hope to bitter scepticism.

But what about their opponents, the Chinese Communist Party? Or, for that matter, the minor parties like the Democratic League and the Youth Party, representatives of which also took part in the Political Consultative Conference? ‘On the list of Chinese officials on whom I was expected to call’, Copland wrote, ‘no provision had been made for the leader of the Communist Party or any other Parties outside the Kuomintang’. Copland had to arrange such meetings privately. It was not that he was in any way starry-eyed about the Communists. Wary of their anti-democratic ideology and having heard reports of the brutality of their land reforms, he wrote that: ‘I would feel happier if the battle for a democratic constitution in China were being conducted by somebody other than the Communists’. Nonetheless, he managed to arrange a meeting with Chou En-lai, the Chinese Communist Party’s envoy to the peace negotiations:

[Chou] opened the conversation by paying a graceful compliment to Sir Frederic Eggleston, whom he knew well and respected highly. He then referred to the fact that Australia seemed to appoint scholars as her diplomatic representatives. This has been a constant source of amusement to me, and it has always been possible to turn it off by saying that when you are in China you must do as China does and show some respect for the scholar. … He is rather more restrained in discussion than some of the more vociferous people I have met, and has a very strong underlying sense of humour. I hope to see more of him.[13]

With the war over and the political conference under way, the next task for the Chinese government was to relocate back to its pre-war capital of Nanking. During April 1946, the Australian diplomatic mission was occupied with preparations to join the exodus. Most diplomatic representatives arrived in the old capital by 5 May, which Chiang Kai- shek declared to be a day marking the government’s ‘triumphant return to Nanking’ 凱旋南京. Copland handed responsibility for the relocation to his Third Secretary, Barry Hall, while he travelled north ‘to see China as it was in the spacious days — or at least to form some impression of life in the old concession areas, and how it has been affected by the war and the abolition of extraterritoriality.’[14] At the invitation of the British Ambassador, Horace Seymour, Copland visited the formerly Japanese-occupied cities of Tsingtao in Shantung province, Tientsin and Peiping.

As the RAF aircraft in which Copland was flying approached Tsingtao, he was struck by the sea-side city: ‘a string of American warships at anchor in the bay, green fields in and around the scattered city … wide streets with well-built modern houses’. The place ‘made a far more pleasing impression on me than has any place in China so far’; yet Copland was also aware that Tsingtao, as well as Tientsin and Peiping represented ‘pockets of government resistance’ within a Communist-dominated countryside. Only a huge US military presence — some 50,000 US marines were stationed in those three cities alone — ensured that both parties adhered to the ceasefire.[15]

In her study of the Chinese Civil War, Suzanne Pepper writes that ‘the carpetbagging [Nationalist] official from Chungking became the hallmark of the reconversion period’ — the months in which tens of thousands of government soldiers and officers, many of them travelling in American planes, were ferried ‘back east’ in the wake of the Japanese surrender. ‘According to his [the carpetbaggers’] popular image,’ she writes, ‘he had five preoccupations: gold bars, automobiles, houses, Japanese women, and face.’[16] Copland observed popular outrage at the carpetbaggers first hand. Locals in Tientsin and Peiping told him that ‘they had been better off under Japanese control’, while the behaviour of the Nationalist government — which was returning ostensibly to liberate them — evoked memories of the brutal warlords who had ruled China during the 1910s and 1920s. In the eyes of many, Chiang’s government was well on the way to ‘snatching defeat from the jaws of victory’. Many, Copland wrote, ‘[compared] their position with what it might be if the Communists were in full control’.[17] For the Australian Minister, the prospect of a Communist victory in the Civil War seemed neither unrealistic, nor too far off. On his last night in Tsingtao, Copland slept badly due to the constant crackle of gunfire coming from the outskirts of the city.

Less that one month after he had settled in at the new Australian Legation in Nanking, Copland had come to some important conclusions about the prospects of the Nationalists and the probable effects of American intervention in Chinese politics. In a despatch to Canberra dated 4 July and marked ‘MOST SECRET’, he recounted a ‘long and frank’ conversation with Tillman Durdin, a veteran New York Times correspondent who served as an advisor to the US envoy George Marshall. Durdin wanted to ‘sound me out’, Copland wrote, ‘on a proposal he had been thinking of making to Marshall’. For his part, Copland reported:

I had been thinking a good deal about the long term implications of American intervention in China, and I was able to underline his [Durdin’s] fears that it would not produce political reform, that it would leave all the abuses of the land and financial systems practically untouched, that it was in danger of producing one of the worst systems of exploitative capitalism the world had known, that it would lead in the end to much dispute between the Chinese Government and the Americans with a new anti-foreign campaign, and that all this would be balm to the soul of the Communists and greatly to the advantage of Russia.[18]

Nanking, the ‘Glorious Village’

William Sima

The city of Nanking, a glorious centre of commerce and culture from Ming times in the late fourteenth century, had never fully recovered from the depredations of the Taiping Civil War in the mid-nineteenth century. That war — to that date the longest, and bloodiest, civil conflict in human history — left the Lower Yangtze Valley, where Nanking is situated, a depopulated Trümmerfeld, so much so that in 1930 the noted essayist Lin Yutang could describe the place as little more than a ‘glorious village’:

[I]ts little hills and undulations in the city topography, its cabbage fields and poultry yards, its horse carriages plodding drowsily along narrow alley-ways, and the general appearance of desolation and extreme rusticity inside the city limits.[19]

By the time Copland arrived in Nanking, in May 1946, swathes of land within the ancient city walls were still devoted to agriculture. The Minister’s offcial residence was located to the west of the city centre on a hill in a district known as The Hall of Returning Clouds, proximate to the Yangtze. It offered a vista of the surrounding countryside. As Copland wrote to his wife Ruth, who was at this time still in Australia:

The sun is setting on Purple Mountain and there are low hills all around to the left and in between fields and trees, still green with leaves showing the first signs of losing their colour, and the corn fields taking on a yellow hue. The peasants are working in their fields and people are wandering aimlessly on the roads, and you would think that China was really the land so often described in books.[20]

The residence (or, in official parlance, ‘the Legation’) boasted a swimming pool, where Copland’s staff spent a lot of time during the blistering summer months, and a yard large enough to host garden parties and games of cricket with members of the British Embassy. But many visitors confused the Copland residence with the Chancery — the site of official diplomatic business, which was located in the main part of the city — including once guests for a dinner party that the Minister was hosting for local university professors: ‘The four who turned up late [having gone to the Chancery by mistake] were from Ginling College, including the distinguished principal, Dr Wu Yi-feng, probably the most able woman in the land’, Copland wrote to his wife. ‘She had been here before and had had trouble [with the address] on that occasion’.[21] Copland’s own commute between the Legation and the Chancery was unproblematic as he had a driver although, as he told his close friend and former teacher, the economist Lyndhurst Giblin, on most days he preferred the two-mile walk into town: ‘it is across almost open country within the city walls and in these still Autumn days the landscapes are extraordinarily attractive.’[22]

In 1929, shortly after the Republican government had been installed in Nanking, urban planners began transforming the gracious, if down-at-heel, old town known to its residents as Chin-ling 金陵 (‘Golden Hills’) into a modern capital city, new suburbs of which were in part inspired by another planned city, Canberra. Some of the older suburbs to the west of the Drum Tower, in the heart of the old city, were demolished to make way for a ‘High-Level Residential Zone’.[23] There, grand mansions for officials, the wealthy and foreign diplomats were built in keeping with contemporary architectural trends and the latest standards of hygiene. An Australian Chancery was opened in the heart of this district at 34 Peiping Road in June 1946, before moving to a second location in early 1948, at nearby Yi Ho Road. ‘We have the British Counsel next door and the Canadians at the end of the street’, wrote Barry Hall in a letter home. It was ‘just as if a large chunk of Toorak was liberally sprinkled with foreign diplomats of all descriptions’.[24]

protected sites in the ‘Yihe Road Republican Architecture Complex’ 頤和路民國建築群. Photograph by William Sima.

The mayor of Nanking, Shen Yi 沈怡, lived in a modern stucco house at 38 Peiping Road which was mockingly referred to as ‘the White House’ due to its resemblance to the presidential residence and workplace in Washington. Shen and his wife, ‘first lady’ Inyeening Shen 沈應懿凝, would become good friends of the Coplands following Ruth Copland’s arrival in mid 1947. Inyeening Shen later wrote that she found the Australian couple ‘affable and sincere, without the hypocritical politeness … so often seen as the only social amenity of many of the other diplomats.’ Copland, she also noted, ‘frequently presented lectures in Nanking, at universities and other education institutions. He also took pleasure in going to other cities in China by invitation from local universities. We met more often in academic gatherings than at diplomatic functions.’[25]

The Australians also made friends with the university lecturer, translator and bon vivant Yang Hsien-yi 楊憲益. Yang and his English wife Gladys (the daughter of a British missionary) lived nearby and were frequent guests at legation functions, including the celebration of Australia Day in 1948.[26] Yang Hsien-yi taught English and Byzantine history at two local universities. Despite this, and as a result of rampant inflation, he only made the equivalent of eight dollars a month, an amount that could merely buy the equivalent of two sacks of flour.[27] Bill Hamilton, the mission’s accountant, who later served as Bursar, then Registrar, of ANU, recalls that on one occasion he lent money to the Yangs, which Hsien-yi repaid with a set of Japanese woodblock prints.[28]

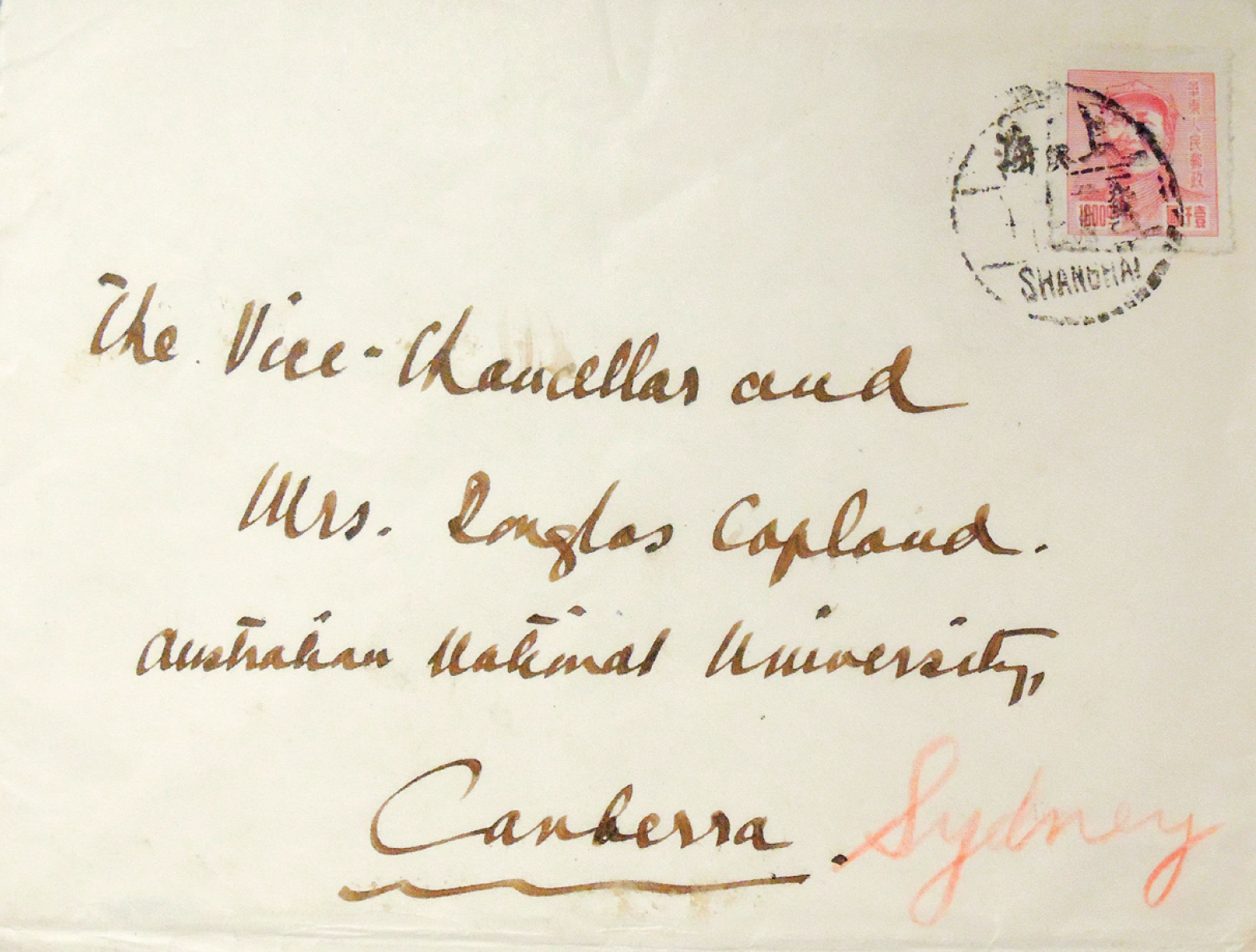

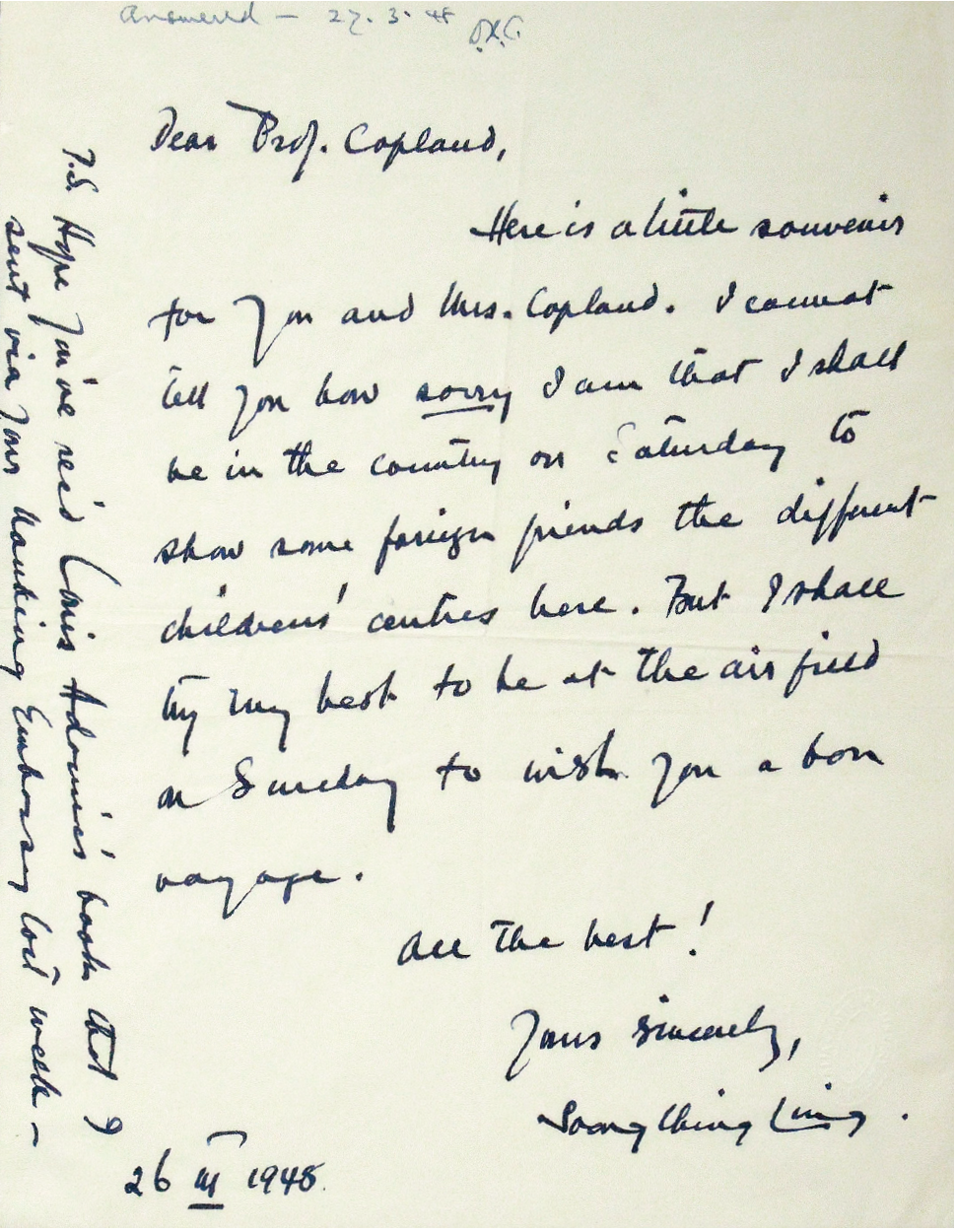

Copland was naturally cordial in his dealings with members of the country’s political establishment, but his real sympathies lay with the students and intellectuals protesting against the Civil War. Copland found the despotic and violent behaviour of the Nationalists — including the brazen assassination of the outspoken liberal poet Wen Yi-tuo 聞一多 in Kunming, in July 1946, after he likened Chiang Kai-shek to Hitler and Mussolini — as well as their corruption and lack of concern about inflation to be repugnant. One of his most prominent contacts was Soong Ching-ling 宋慶齡, the widely-respected widow of Sun Yat-sen (and sister of Chiang Kai-shek’s wife, May-ling), who the Australian diplomat met in September 1946 after lecturing at the Shanghai Rotary Club. An outspoken opponent of the Civil War, Soong — a public figure who, despite her lofty status, was under surveillance as a Communist sympathiser — admired Copland’s liberal opinions. ‘Madame Sun will welcome you here,’ Copland wrote to Ruth, shortly after that first encounter. ‘She has been reading my address at the Rotary Club & said that she was pleased that I was a liberal — we had a talk about China & agreed that progress could only come through the adoption of a liberal policy’.[29]

In September 1946, the British writer and historian Charles Patrick FitzGerald, who would eventually establish the Chinese Studies programme at ANU, arrived in Nanking to work for the British Council, which was also located on Peiping Road. He recalled with humour his first introduction to the Australians who lived over the road: the windows of the Australian Chancery did not have curtains, and FitzGerald caught sight of the Australians, Charles Lee, Barry Hall and Lionel Phillips, while they were undressing.[30]

FitzGerald had been fascinated with China since his school days in London and, after having found himself a job in China at the age of twenty-one, had lived and travelled in the country for over ten years. During this first China sojourn, from 1923 to 1928, he studied Chinese in Peking and worked as a depot clerk on the Peking-Mukden Railway. In 1927, while working at the International By-Products Company in Hankow — ‘the euphemistic name’, he said, for a company which turned pig guts into hot dog casings for export to America — he witnessed the siege and capture of that city by Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist forces during the Northern Expedition.[31]

FitzGerald’s formal education, which later proved to be a matter of some contention among his prospective employers at ANU, consisted of a Diploma of Mandarin from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London, which he completed in 1930 shortly after returning from his first stint in China. By the time FitzGerald met Copland and his fellow Australians in 1946, the British clerk and adventurer turned scholar had built up a formidable knowledge of the country and its history. He had also published three significant books: the first, Son of Heaven, a biography of the founder of the Tang dynasty, LiShih-min李世民, appeared in1933 through Cambridge University Press; his second, China: A Short Cultural History, was published by Cresset Press in London in 1935 and was later translated into Chinese, Russian, Polish, Italian and German (it was used as a standard introductory text in high schools and universities up until the 1980s). The year after China was published, FitzGerald was awarded a Leverhulme Fellowship to study the language and culture of the Bai, or Min-chia ethnic minority in China’s southwestern Yunnan province. He pursued this project from 1936 to 1939 and published the resulting book, The Tower of Five Glories, in 1941.

FitzGerald and his wife Sara were soon enjoying frequent contact with the Australians and, like Inyeening Shen, they appreciated the informal friendliness of Copland and his staff. Sara commented that: ‘the Australians were much better at mixing with the Chinese than most of the embassies’.[32] For his part, Patrick FitzGerald remarked many years later:

Chinese regarded Australia as in a different category from the leading nations of the West, the United States, Great Britain and France. … Australia — even more than Canada — was seen as a ‘liberated’ country, which had shaken off colonial bonds. It was therefore treated with sympathy as a potential friend, and as Sir Douglas Copland developed his policy approach, a useful intermediary between the Chinese government and the embassies of the major Western powers. The Communists, who still in 1946 had a mission, headed by Chou En-lai … also saw Australia in this light, and formed good relations with Sir Douglas.[33]

FitzGerald might have been referring to an occasion in September 1946, when Copland received Wang Ping-nan 王炳南, an emissary from Chou En-lai, at the Australian Chancery. He told his wife Ruth that the Communists were ‘actually sounding me out as to whether there was not some form of international mediation that could be adopted to stop the civil war. I must say that I sympathised with them, but I could only say that I would call on Chou early next week and have a further talk. Meanwhile I’ll have to send a message to Canberra about the talk. I don’t expect much response.’[34]

As was so often the case, Canberra was unenthusiastic.

Report on Journey by River Steamer from Chungking to Nanking

21st to 29th May, 1946

Barry Hall

Early in February we started to make enquiries in Chungking concerning the availability of air and river transport for Legation personnel and stores to Nanking, in case the move of the capital should commence within the next month or so. The Canadian Ambassador, General Victor Odlum very kindly offered to assist by including the Australian Legation with his own Embassy in negotiations he was carrying out with the Ming Sung Shipping Company in Chungking. It was then promised that we should be allotted space and passages together with the Canadian Embassy, and that the official freight rate, and not the considerably greater commercial rate, should apply to both our organisations.

At the beginning of April when the move appeared to be imminent, negotiations were recommenced with the Ming Sung Company, by myself and the First Secretary of the Canadian Embassy, Mr Ronning. It soon became apparent that the promises made by company earlier would not be so easy to fulfil, since the Chinese Government through its Ministry of Communications was enforcing rigid control over all river shipping, and had set up a Shipping Allocation Commission to administer this and issue priorities and permits for all river travel.

The Ming Sung Company, although anxious to be of assistance, became powerless to help us in this regard. Our negotiations with the Ministry of Communications were protracted and troublesome, and consisted for the most part of fruitless hunting of the whole of Chungking for the ‘right man’, who never seemed to be in his office when we called. On one fortunate occasion we were shown straight to his office and he had to listen to our story, the messenger boy however was severely reprimanded for bringing us up unannounced, to the great amusement of Mr Ronning, who understands Chinese very well. Mr Ronning, it should be mentioned, bore the brunt of these difficult negotiations. As the move commenced at the end of April and the water level of the river rose, making the resumption of shipping services possible, competition for the few precious passages increased from all sides, particularly from the Chinese Government. …

The actual loading of the ship developed early into a race for first place and we were privately advised by the shipping company to deliver our freight to the waterfront as soon as possible. Since this notice came only twenty-four hours ahead of the time for delivery, we were obliged to do a lot of work in a short space of time in order to complete packing. … The main difficulties were, first, to obtain some kind of truck which would cover the five or six miles between the Legation and the waterfront, and to remove the heavy office safe from the house and onto the truck. Transport became almost impossible to borrow or hire during the concluding stages in Chungking, but we were able through the good offices of the chauffeur, who had friends in the right places, to hire one truck. This broke down consistently, but accomplished the job of shifting both Australian and Canadian freight to the river in two days. The safe was also delivered, but it took twenty coolies most of one morning to move it out of the compound, a total distance of about eighty feet or less. I did not witness it being manhandled down the narrow steep steps leading from the motor road to the actual river, or its loading onto a sampan to go out to the ship, but I can imagine that this must have taken a great deal longer. …

We were given twenty-four hours notice by the shipping company that the ‘Ming Peng’ would leave on the afternoon of May 21st, and made plans accordingly. Our large party of men, women, children and baggage required a great deal of marshalling and keeping together in one place. By the time they had been transported to the river front, loaded onto a sampan and taken out to the ship, it was past midday and most of the passengers were already aboard. Even when viewed from a long way off, it was obvious that the ship was overflowing and that considerable effort would be needed to fight out way up the gangway, let alone find an empty space. The large quantities of furniture hung over the railings and the heaps of baggage along the decks gave the ship a particularly weird appearance. … At 3 o’clock the a Chinese General embarked and the ship left almost immediately. The General turned out to be Lung Yun, the ex-Governor of Yunnan, apparently being taken to Nanking where the official can be kept on him. He had a number of steel helmeted guards in attendance. We did not see anything of him during the voyage, except for one excursion which he made on shore later on. …

Later on a number of people left the ship at the various ports of call, but that was offset to some extent by the number who used to sneak aboard without any tickets. According to our observations these included a Major-General of the Chinese Army, who was reported to have forced his way on to the ship with a drawn revolver. …

We finally arrived at Nanking at 10am on May 29th, having made a remarkably rapid journey. The freight arrived in reasonably good order and at least dry. There were some small breakages which were to be expected with old furniture and the inevitable rough handling by the coolies. There was some delay in having it unloaded from the ship.

— from ‘Despatch no.35’, National Archives of Australia A4231 1946/NANKING Part 2. See here for the full text of this despatch .

Notes from Old Nanking

William Stenhouse Hamilton

Three Furnaces

Nanking was stigmatised as one of the ‘Three Furnaces’ of China (along with Chungking and Wuhan). In Winter the minimum temperature rarely went below -4°C but the days were often dark and wet, and occasionally snow fell. The streets would become slippery and broken surfaces and shoulders made driving hazardous.

Summer was a real stinker. The average maximum temperature in July and August of 33°C would, in many parts of China, be regarded as a relatively cool day. Nanking was not so much a furnace as, more properly, a steam bath. The great burden was high humidity, which was unrelenting through night and day. In nearby reaches the Yangtze River was only 1,300 metres wide (though many times that during floods), but it was bordered by vast tracts of rice paddies which were under water for much of the summer.

We plain folk who did not run to the luxury of air-conditioning had recourse to the peng. At the onset of summer a team would come with bamboo poles eight to ten metres long and woven fibre mats about two by three metres. The poles were erected as scaffolding over the house and the mats were laced to it as walls and roof. In the summer of 1948 I lived in a small house which had a ground floor and two upper floors. Once fitted with the peng, it finished up looking like a brown paper parcel. The encasement beat off the sun’s rays, but it also stifled such little air movement as might come along. Still, holding the temperature down made the operation worthwhile. The rickety-looking structure had a surprising ability to withstand wild summer storms.

Our most ready recourse for respite from the heat was to take a boat out on the Lotus Lake in the afternoon or evening. The hire boats were long, low sampans with cane chairs for a dozen passengers and a striped canvas roof in the manner of a Renoir painting. They were poled around the shallow lake by a young woman or man at a pace so leisurely it was insufficient to generate any breeze; but, except in the lull before a storm, there were enough lacustrine zephyrs to delight. On evening excursions we usually embarked just before dusk. At first the course would follow the shore and we could watch people sitting by their cottages binding newly cut bamboo shoots for the morning market or gathering the huge circular leaves of the aquatic lotus which were bought by shops for wrapping food portions.

Near the Cock’s Crow Temple the boat would head out into the lake proper, our presence made known by paper lanterns strung around the canopy. Unusually for Australians, our group included good voices, notably Sylvia, Barbara and Lionel (but not me), and they had a knowledgeable repertoire. Sometimes there would be scraps of music coming from other boats. I remember still the sparse phrases of a Chinese flute, its melody plangent, rather chilling, its cadences unhurried. Soon a huge double-decked and dimly lit carnival barge tracked us briefly, then turned away to disappear along the path of the moon.

During the peak summer months we started work at the Chancery at 7am and finished at 1pm. After a very light lunch one rested through the afternoon in front of an electric fan; or, more agreeably, hied off to the swimming pool at the American Embassy. There was more: it is an unfortunate fact that the national days of many countries are in July, e.g. the United States, France, Canada, Belgium. And so, and the end of the afternoon, one showered then crawled, muttering, into an immediately sweaty suit and went off to yet another formal function. The only celebratory party with any style was that at the British Embassy to mark the King’s birthday. Our drivers hated the occasion. The cars lacked air conditioning and were best kept cool by parking under the huge trees in the Embassy compound. These, alas, were the roost of a large colony of white egrets which showered the cars with generous squirts of white and very runny cack.

During summer the climate passed through a phase called the ‘Yellow Mould’ period. It had one benefit for local shoppers by bringing the price of cigarettes down; holders of tobacco stocks sold out fast at bargain rates before the humidity and heat turned their goods mouldy. About the third week of July the Chinese calendar moved into the ‘Big Heat’ period; and worse, at the same stage of August we would suffer the ‘Tiger Heat’.

A skin rash known as prickly heat was a day and night scourge during the humid months. There was a belief that exposing the body to rain brought relief and desperation drove me to experiment in the walled garden of our compound. The alleviation was brief. The servants had undertaken to observe my wish for privacy but I think Amah peeked — our next few encounters brought on giggles, with her hand over her mouth in feigned embarrassment.

At the Australian Embassy

The Australian Embassy in China in my day occupied rented houses, Chancery and all. The Nationalist Government had moved from its wartime refuge in Chungking to Nanking in 1946; the all-conquering Communist regime set up its capital in Peking late in 1948. When I arrived, the Chancery was in a modest house in Peiping Lu and in 1948 moved to a somewhat larger but equally unprepossessing house in Yi Ho Lu.

My first Head of Mission was Professor Douglas Berry Copland, whom we addressed, except in formal circumstances, as ‘Prof’. He was born in New Zealand in 1894, the 13th of 16 children and was proud of his farming background. After graduating in economics, he took up an academic appointment in Australia in 1917 and thereafter pursued a distinguished career as an economist, bureaucrat and diplomat.

Prof had a formidable presence, he was ebullient, gregarious and conscious of his role. He was highly regarded in Nanking’s official and diplomatic circles, first because he was a scholar but also because he could carry his grog — attributes which in China were held in awe and affection in equal measure. Prof returned to Australia in March 1948 to become the first Vice-Chancellor of the new Australian National University in Canberra.

Though I have decided to give my Australian colleagues the courtesy of anonymity, I am impelled to say a little about Charles Lee, because he was an engaging character who held a unique position in Nanking. Charles was born in Darwin, of Cantonese parents and spoke only Cantonese until he was eight years of age. He was a graduate of the University of Queensland and had played in the rugby team representing that State. He was bilingual in English and Cantonese, read Chinese and had acquired fluency in Mandarin and Japanese along the way. He was a puzzle to many; here was man in China who was clearly Chinese but who represented Australia. His friendships ramified through many circles and layers. New of political events often reached Canberra before it was known in Nanking any great distance from its origin.

The local staff included three translators who worked on public material such as political, cultural and financial articles in newspapers and journals. (Australian staff who could read Chinese looked after confidential material). Then there was an office manager who operated the modest telephone switchboard, rostered the three drivers, arranged vehicle maintenance and directed the messenger/gardener.

Among these were three men all by the name of Liu: Lao Liu (‘old Liu’) who drove the Ambassador’s Cadillac, and who was probably fifty years old, personable, sedate and aware of his standing; Hsiao Liu (‘little Liu’), the driver of the general-purpose station wagon. Plain ‘Liu’, the office manager who had joined our staff in Chungking, was a treasure: he was never flustered, always cordial and helpful and not in the least servile. He looked about eighteen years of age but, when I got to know him, I learned he was thirty-two and had eight children. When I came to know him even better, he told me his household ate rice at each meal, mostly with a little soya-bean curd … some green vegetable and a few drops of soy sauce for flavour; about once a week each had a scrap of dried fish, once a month some chicken or duck, and pork only at New Year feasts. …

There is anther member of the local staff I want to mention. Fong, the messenger/gardener, was tall, skinny, snaggle-toothed, illiterate and a gentleman. He did not have any English and his Chinese was as incomprehensible to me as mind was to him, but we got happily. He was known as the t’ing chai — a term for a messenger.

The Chancery was never unattended. The Australian male staff took turns to be resident duty officer after office hours and through the weekends. There was some flow of cables, but mostly the time could be given over to reading or language study; there was occasional relief of the tedium. One Sunday morning I took a telephone call from a British Vice-consul in Canton who said he had received a cable from Canberra to the effect that Dr HV Evatt, the Australian Minister for External Affairs, would be passing through Canton that afternoon and it was assumed customary courtesies would be extended. He asked whether I could confirm the message? It was widely known that Dr Evatt was not always an easy guest, inclined to be heavy on protocol and my caller was clearly in a bit of a dither. I replied that we knew nothing of a visit to China by our Minister; indeed he was about to leave for America to attend a meeting of the United Nations (of which he had been something of a founding father and would soon commence a term as President). I said I would check and call back.

As soon as I ended the call the penny dropped. Non-stop flights between the West Coast of the United States and Australia by jet aircraft were far in the future and the piston-engine planes of the time had to make refueling stops along the way, sometimes involving overnight rests. One of these places was Canton Island, a cay in the Phoenix Group about a third of the way across the Pacific Ocean, and it seemed clear the cable had been misdirected. My Canton caller’s relief was vehemently expressed.

— from Notes from Old Nanking, 1947–1949, Canberra: Pandanus Books, 2004, pp.45-48 & 55-59.

Notes

[1] Despatch no.50, ‘VP Day’, 16 August 1945, p.1, National Archives of Australia (hereafter NAA), A4231, 1945/NANKING.

[2] Despatch no.101, ‘Communism’, 10 August 1943, p.2, NAA A4231, 1943/NANKING PART 2.

[3] Despatch no.55, ‘Events During August’, 5 September 1945, pp.1-2, NAA A4231, 1945/ NANKING.

[4] Despatch no.7, ‘Legation Report’, 27 January 1945, p.4, NAA A4231, 1945/NANKING.

[5] Marjorie Harper, Douglas Copland: Scholar, Economist, Diplomat, Carlton: Miegunyah Press, 2013, pp.225-226.

[6] ‘Canberra Gossip: Autocrat Overnight’, The Advertiser (Adelaide), 30 September 1939,p.23.

[7] Margaret Lundie, Never a Dull Moment in China: Pleasures and Problems of Legation Life, Roseville: Orana Press, 1987, p.iv.

[8] Despatch no.17, ‘Presentation of Credentials’, 26 March 1946, p.1, NAA A4231, 1946/ NANKING PART 1.

[9] Despatch no.23, ‘Discharge of Diplomatic Courtesies’, 17 April 1946, p.1; and, Annex A, ‘Discharge of Diplomatic Courtesies’, p.1, NAA A4231, 1946/NANKING PART 1.

[10] ‘Discharge of Diplomatic Courtesies’, p.4.

[11] ‘Discharge of Diplomatic Courtesies’, p.3.

[12] Henry S Albinski, Australian Policies and Attitudes Toward China, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965, pp.6-7. The UNRRA figure of £6,563,000 is approximately $450,000,000 in 2015.

[13] ‘Discharge of Diplomatic Courtesies’, Annex A, ‘Discharge of Diplomatic Courtesies’, p.4; and, Annex C, ‘Miscellaneous Notes on Further Discussions’, pp.1-2. Emphasis in the original.

[14] Despatch no.27, ‘Visit to Tsingtao and Tientsin’, 21 May 1946, Annex A, ‘The Spacious Days in China’, p.1, NAA A4231, 1946/NANKING PART 1.

[15] Despatch no.25, ‘Visit to North China’, 13 May 1946, p.1, NAA A4231, 1946/NANKING 155 PART 1.

[16] Suzanne Pepper, Civil War in China: The Political Struggle, 1945–1949, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1978, p.16.

[17] ‘Visit to Tsingtao and Tientsin’, Annex A, ‘The Spacious Days in China’, p.8.

[18] Despatch no.49, ‘The Truce Discussions: Some Reflections’, 4 July 1946, pp.1, 4, NAA A4231, 1946/NANKING PART2.

[19] Lin Yutang, ‘The Little Critic’, The China Critic, vol.III, no.49 (4 December 1930): 1165-1168, at pp.1165-1166. [Link to Lin Yutang essay in Annual]

[20] Letter, Copland to Ruth, 4 September 1946, National Library of Australia (hereafter NLA), MS3800, Box 158.

[21] Letter, Copland to Ruth, 18 September 1946, NLA MS3800, Box 158.

[22] Letter, Copland to Giblin, 12 October 1946, NAA A4144, 270/1946.

[23] For details of Nanking’s ‘Capital Plan’ 首都計畫, see Charles Musgrove, China’s Contested Capital, pp.55-88. [Link to Musgrove and Annual selections from The China Critic]

[24] Letter, Barry Hall to his mother, 31 May 1946, provided to the author by Diana Hall. Toorak, in Melbourne, was at this time and remains today one of Australia’s most affluent suburbs.

[25] Jane Shen Schopf, ed., My Years in Nanking: Reminiscences of Inyeening Shen, Bloomington (Indiana): iUniverse, pp.90-91.

[26] Despatch no.15, ‘Australia Day, 1948’, Annex B, ‘Informal Reception on Sunday, 25th January on the eve of the Australian National Day, at 26 Yi Ho Lu, From 5:30 to 7:30 PM’, p.4, NAA, A4231, 1948/NANKING PART 1. Margaret Lundie (in Never a Dull Moment in China, p.108) notes that: ‘We did get to know some Chinese well, notably Yang Hsien-yi and his China-born wife of English stock, Gladys. They lived quite close to us. In order to supplement their salaries, ravaged by infation, they used to sell pottery and miscellaneous curios.’ For an account of Yang Hsien-yi and Gladys Yang’s relationships with later generations of Australian scholars, and a tribute to Yang Hsien-yi following his death in November 2009, see China Heritage Quarterly, no.25 (March 2011).

[27] Yang Xianyi, White Tiger, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 2002, pp.152-154.

[28] Author’s interview with Bill Hamilton, 21 August 2014, Canberra.

[29] Letter, Copland to Ruth, 30 September 1946, NLA MS3800, Box 158.

[30] Stephen Foster, ‘Interview with Emeritus Professor CP FitzGerald’, 2 May 1991, ANU Oral History Archive, online at: http://www.anu.edu.au/emeritus/ohp/interviews/cp_fitzgerald.html.

[31] CP FitzGerald, Why China?: Recollections of China, 1923-1950, Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1985, p.85.

[32] Lundie, Never a Dull Moment in China, pp.99-100.

[33] CP FitzGerald, Why China?, p.211.

[34] Letter, Copland to Ruth, 18 September 1946, NLA MS3800, Box 158.