Lin Yutang 林語堂

Here we reproduce the first of two related travel sketches from Lin Yutang’s ‘The Little Critic’ column written for The China Critic and published on 4 December 1930. The title has been added.

— William Sima, Associate Guest Editor

Nanking is a glorious village. A few days ago, I spent there what I considered to be one of the most beautiful days in the country that I had had for two years. After walking daily on the cement pavements under the shadow of the rectilinear, disinfected and anaemic streets of the Shanghai Settlement, one was glad to be back in nature. One had heard of the water supply, the electric light and the road conditions in Nanking from friends there, one would have imagined that the city was an unbearable sort of place to live in, and I know actually many wives of the Nanking government people have refused to go to live in the capital. The last visit entirely changed my opinion, and I now consider wives who refuse to follow their husbands to Nanking, leaving them to eat at restaurants or hop from one friend’s home to another, deserve all the consequences to themselves. A man who cannot appreciate the rural beauties of the nation’s capital must be a vulgar, unpoetic soul indeed.

For, contrary to my expectations, I found an atmosphere of quaint charm, peace and repose there which nobody had told me about. I did not go to Nanking to visit the ministers, or to see the Chungshan Road or the Mausoleum, but I went to see the famous Nanking ducks. And I believe I have succeeded in doing so, in appreciating the spirit of rustic charm of the city, its breadth, its historic colour, and its true grandeur. The magnificence of its city walls, the weird, wild lakes outside the city, full of swaying reeds and lotus stems, its little hills and undulations in the city topography, its cabbage fields and poultry yards, its horse carriages plodding drowsily along narrow alley-ways, and the general appearance of desolation and extreme rusticity inside the city limits: all contribute to that soothing and broadening effect on the mind. These things at once and instinctively reconciled me to the city which no official propaganda could have done. In fact, the sight of one fat beautiful Nanking duck warbling on a cabbage field by the roadside had more propaganda value for me that a long-winded official news despatch. I saw also a man brushing his teeth outside his door on the Chungshan road—a sight one would have prayed for in vain in Shanghai that was what I called true rusticity. It suggested peace of mind.

We arrived early in the morning, with the mist still hanging over the city. As I had lost track of my colleagues, I could not avail myself of the car which was coming to meet us, and so I took a hire taxi. After a moment’s remonstrance with the engine, and a few thorough shake-ups, the chauffeur succeeded in starting the car, pressing the metallic horn energetically in order to clear a headway among the rickshaw wheels, human legs and horses’ hoofs in front of us. I noticed ours was an open car, but in fact it was a Nanking Phaeton, the hood being provided by local hands with Nanking bamboo for the cross-supports, giving peculiar squeaks as we bumped along the road. I asked whether it was a Ford, but the chauffeur proudly told me that the engine was an old Buick, the chassis a renovated Chevrolet. I figured we were going at about twenty miles an hour, and wished to form an idea of the distance of the road we travelled. I looked at the speedometer, and found the meter missing, although the board was there.

Still we made a fast, though noisy, journey. As I wanted to gain a better view of the streets, I ordered the side panes to be taken down, and the chauffeur was cursing all the way and complaining of the cold draught. Policemen stood in the middle of the road, making signals with their hands to let us pass. The mist was rapidly passing, and shops were opening. A beautiful day was ahead of us. We passed the Railway Ministry with its famous stone lions, on our left, and a huge yellow factory building on our right. I enquired from the chauffeur what it was, and he told me it was the Ministry of Justice. I told him that he was probably mistaken, that it must have been some model prison under the Ministry of Justice, but the fellow insisted that it was the Ministry itself, and the fellow seemed to know. Something began to annoy me inside my socks. Scratching brought no relief. [What] I found there was a group of red marks, arranged like Diamond Five on the cards. Later on, I was told it was the work of the famous Nanking bugs, christened by the Japanese as ‘Nanking mushi.’ I had thought they were to be found in gentlemen’s beds only.

So this was Nanking, I thought to myself. And yet I should like to warn prophets of evil and other croakers who are enamoured with their own pessimism that the national capital is still in the third year of its infancy. A distinguished American, whom I had the pleasure of talking with on the train, told me that when the United States changed its seat of government from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C., the European diplomats were equally reluctant to move their legations there because Washington was then a rustic place with chickens, geese and pigs running about. It has taken the United States several decades to make it the beautiful city that it is today. And I must say Nanking has the natural grandeur and general make-up for a future magnificent capital. No one can say what it will be like in thirty years. At the same time, I should like to warn official propagandists that there is no use denying the fact that the most beautiful things to be seen today in Nanking are its dockyards, its desolate lakes, its historic walls, and the swaying reeds and lilies of the valley to which Jesus once made an unkind reference. The most worthwhile things to see in Nanking today are emphatically not the Chungshan Road and not the Chungshan Mausoleum.

Nanking, like Peking, has the magic charm of a semi-mediaeval city. A spell of desolate loveliness hangs over it. People who live long in Shanghai are liable to forget that such things as the horse carriage still exist in the twentieth century. Well, they can go to Nanking and see the nineteenth-century relics. The street scenes strongly remind one of Peking, only infinitely more rustic and more drowsy. The houses are less well-built, less prosperous looking and certainly more straggling in many quarters. Along the Chungshan Road, whole stretches of vacant land or mulberry fields are interspersed with farm houses, poultry yards or mud huts thatched with straw. (I am recording this for the benefit of some future historian). Along some part of the city wall, some low, dismal huts of Kiangpei people nestle snugly by the side of some stagnant pond, giving a picture of wonderful calm and sadness. In the more crowded parts of the city, one sees teashops, dry-goods stores, blacksmiths’ shops, and restaurants of the old type commonly seen in Peking. Some parts of the Chungshan Road strikingly resemble the Hatamen Street of the former capital. Motor cars, with their incessant horn-tooting rush past rickshaws along the asphalt road, while on each side is a broad stretch of unpaved side-walk for more leisurely traffic. On these dusty sides, one sees hawkers of all sorts, standing rickshaws or rickshaws used for carrying pigs, travelling barbers, cobblers, knife-grinders carrying whetstones, horses having shoes put on them, donkeys for hire, cats, dogs, and, as I have repeatedly emphasized, magnificent poultry. Old Noah himself should have been satisfied with this for the Chinese section of his Ark.

I then tried to hunt out my country cousin, as I called him, in my facetious manner. Perhaps the weather had something to do with it. Anyway his home made a hit with me. The beautiful late November sun, the cool, invigorating air, the pleasant garden overlooking parts of the city, the lovely view of the purple side of the Purple-Gold Hills in the distance, and the conversation of my charming hostess in the garden all united to achieve a unique effect. I lamented only that they did not have more poultry, a few tomato plants, some melon-plants, and above all a well, of which Nanking has so many. That would have completed my idea of a perfect home, so different from our corrupted and mutilated version of the home in Shanghai, as well as in all modern cities. I cannot conceive of a home in the real sense of the word without some chickens, some rabbits, a few melon-plants and a well. A home without a well is no home at all, and if I ever had money to build a homestead of my own on Yu Yuen Road, the first thing people would catch sight of from across the gate would be a bucket hanging over a well under some date-tree and a backyard for my children to romp and play about. They would not see any of the mown lawns and fountains and geometric flower-beds of which some of my Shanghai hostesses are so proud. And they certainly would not find me living in those over-heated, cramped, subdivided apartments, with nothing but a combination of buttons, knobs, switches, plugs, wires, cabinets and burglar alarm devices which they call a home. To carry out my idea of a home presupposes that it must be possibly for the home to arrange itself commodiously in space, but modern city civilization has developed to such a point that a well is simply a luxury that no middle-class family can ever afford and no villa-owning family has ever the sense to provide. It takes good taste to appreciate the good things of life and good taste and the habit of owning villas don’t happen to come together often. Anyway I told my charming host and hostess that if they had a well in their home (as they well afford it at Nanking), I would make these periodic descents into the country more frequent.

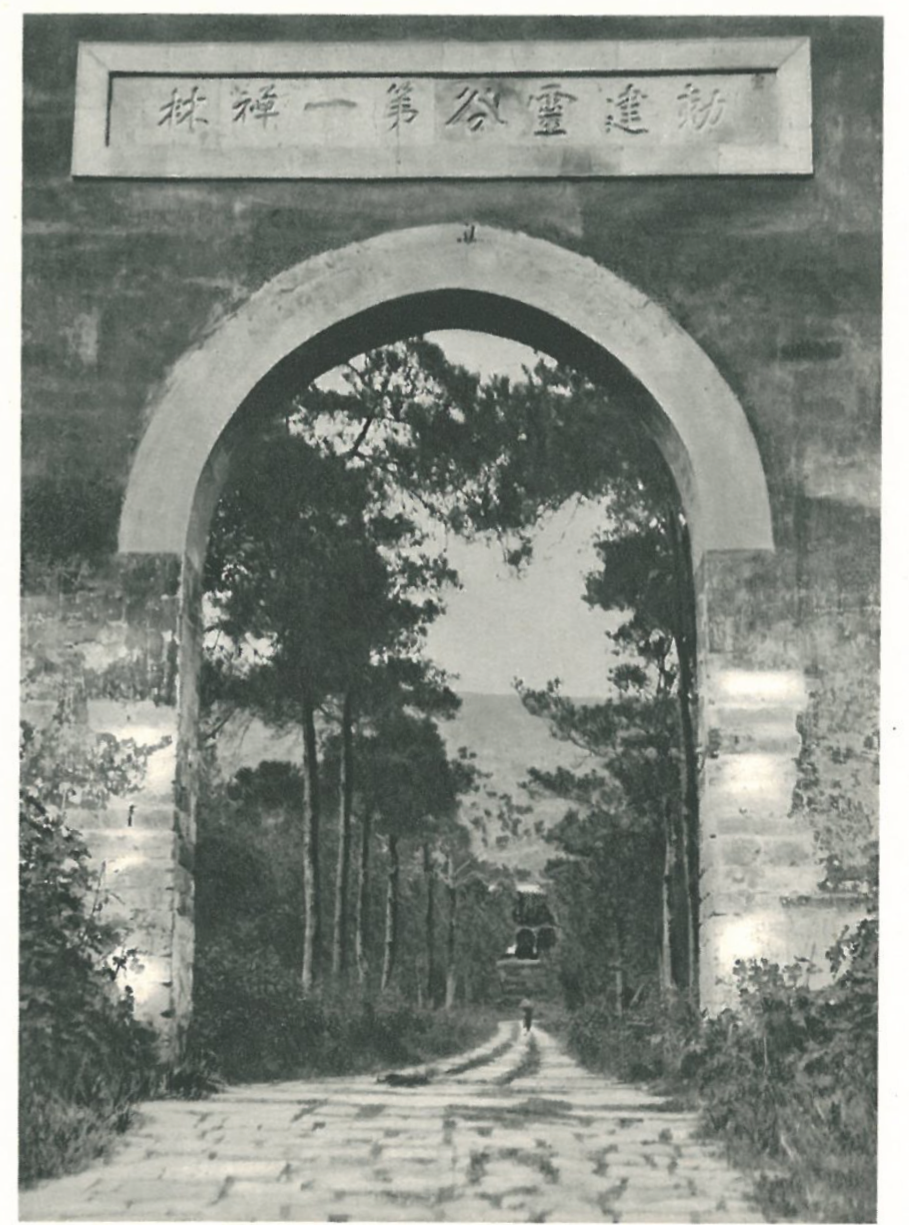

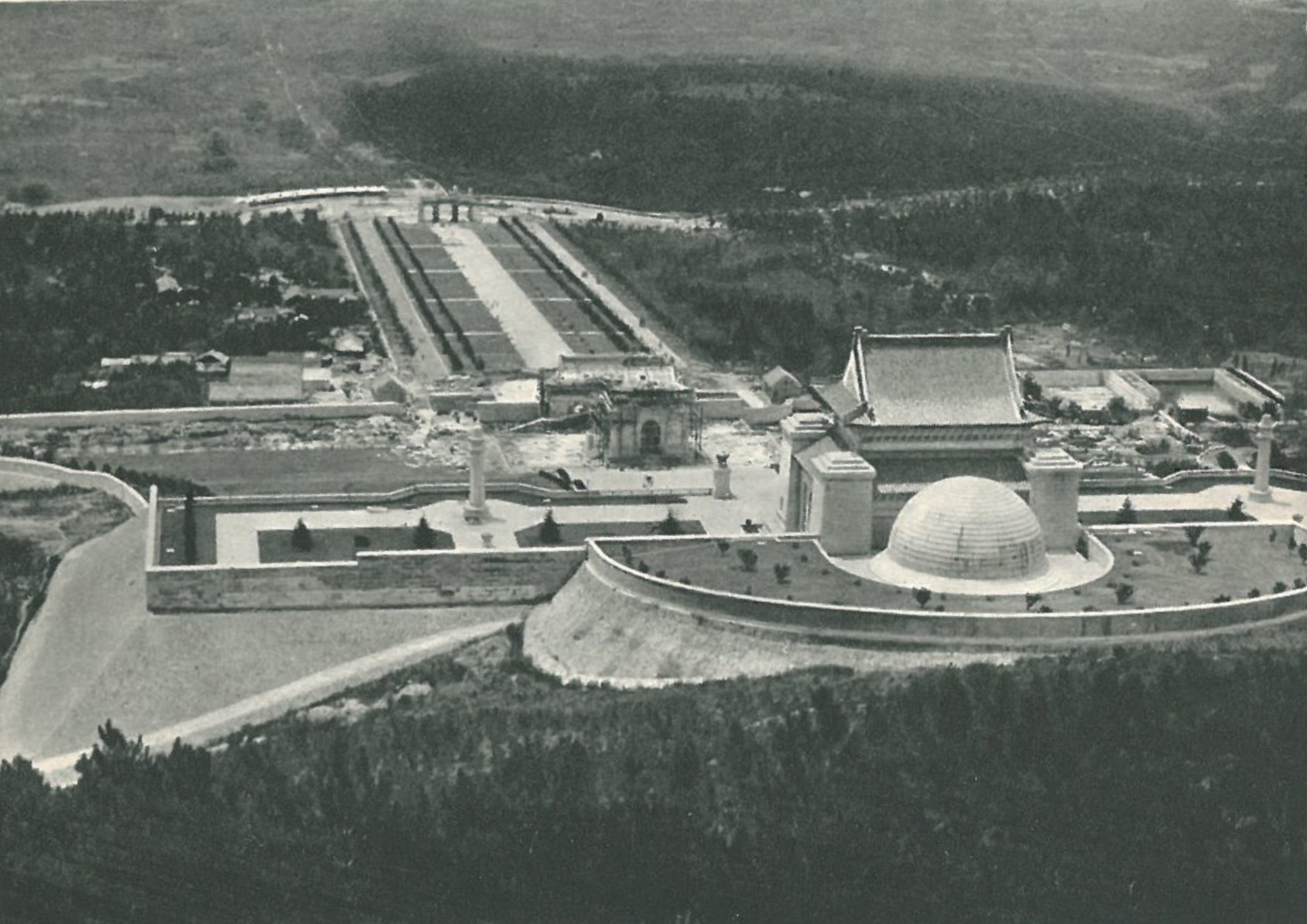

The late November sun was so cheerful and inviting that we decided to go out for a stroll to Lingkoshih. We managed to get a car to take us to the place. I remembered it was late autumn, and I expected to see some of those beautiful maple trees with their gorgeous red leaves. Later I was told we were going to pass the Mausoleum on our way. Both were situated at the foot of the Purple-Gold Hills, outside the city, on the east. And we did pass the Mausoleum. I was told that its famous designer was dead. I regretted that he did not live to see the ugliness and lack of proportion of his mental product. All of a sudden, it dawned upon me that it would be as hazardous to expect graduated and diploma’d architects to possess artistic genius as to expect any B.A. with honors in literature to write a literary masterpiece. These things are inborn and not acquired from studies. All the same, I regretted that the Chinese nation did not have an artistic genius with an artistic conception of enough simplicity, grace and grandeur worthy of our great national leader. Whatever one says, the present decade is certainly not the great epoch of China’s architecture. The Mausoleum does not have the old Chinese grand style; it lacks the broad sweep of outline, the magnificence and calm suggested by the Temple of Heaven, the graceful austerity and complete union with nature that are characteristic of the true Chinese tradition. It does not fit in with the background of nature, but rather stands out glaringly against it, like a cheap jewel of white paste on a crown. The white does not blend with the purple and hazel of the mountain sides. A little touch of pastel purple in the scheme would have achieved that desirable blending of effect. Stones of this shade are to be found on the spot, the kind from which ink-slabs are made and for sale at the Lingkoshih. And it isn’t in the best western tradition, having neither the Greek simplicity and grace, nor the Gothic sublimity, nor Indic ornateness. It is in the style of the new German school of reinforced concrete, minus its suggestion of Power. The most obvious defect is its lack of proportion. It looks like one of those caricatures of Japanese stage actors, with enormous, square, pointed shoulders and a small head. The descending steps fall into a series of graceless, ramping slovenly zigzags, resembling the Japanese actor’s mantel in folds as represented in some atrocious woodcut. And I was told the designer had forgotten to calculate the slope required for a comfortable grade in the upgoing steps. Why the whole contour of the piece of engineering should be such a perfect rectangle with pointed corners is beyond my understanding. Could not façade mount upon façade, approaching the edifice from all angles in concentric fashion and unite to pay tribute to the central edifice in holy worship and glad piety? Could not a series of balustrade terraces encircle it and gradually usher the pious visitor to a more magnificent central hall, like those which serve to uplift the Temple of Heaven and grace the Taihotien? And could not the classic sag of Chinese temple roofs, if it must be imitated here, be made to suggest a little more sweep and freedom?

But human atrocities apart, everything was all right, and even beautiful with nature. The setting sun was casting a real golden purple on the Golden-Purple Hills, reflected through an autumn foliage of variegated richness. Towards the south, the country was of the undulating type, rolling in magnificent ups and downs. Looking westwards I saw the city enveloped in a mist of hazel and blue. It was told that model settlement for the residence of the officials would be built in this region in the future, and I had no doubt that, contrary to the way of the world’s big cities, the fashionable section of the future would be on the East Side. Strolling up into the autumn woods, we saw some remnants of those red maple leaves. A light, dry breeze sent the trees shivering with cold and shedding noisy leaves down through the air. My thoughts went back to the spirits of the Ming Emperors, whose ruins I was trading at every step. … We met here a Nanking minister in riding breeches, and I began to understand what makes politics endurable in this city.

As the sun was already sinking into a cloud of blue mist at quite a distance from the horizon, and I considered we had reached the end of a perfect day in the autumn woods, we decided to come back. That night I took a night-train, and returned to civilization.

Source

The China Critic, vol.3, no.49 (4 December 1930): 1165-1168.