David Hawkes

The Chinese equivalent of the sack of Rome occurred in A.D. 311 when [the capital of the Latter Han dynasty] Luoyang fell to the barbarians. As many better-off Chinese as could get away fled south, where a Chinese court had established itself in Nanking. Thereafter, for three centuries, North China remained in the hands of foreigners, while a series of increasingly murderous native dynasties, each based in Nanking, continued to maintain a precarious hold on the South. This political Dark Age, which Western historians of China call the Age of Disunity, was, surprisingly enough, a period of remarkable cultural development. Buddhism, the religion of peace, flourished in this bloody period. Still an outlandish, exotic religion in the third century, by the fifth it numbered princes and emperors among its devotees, and distinguished men of letters not infrequently found a refuge in its monasteries. Indian Buddhism for the first time brought the Chinese in contact with a literate, highly developed foreign culture. The experience taught them many things about their own. It made them realize, for instance, that they spoke a tonal language — a discovery which was to have a profound effect on their literature, particularly their poetry. Above all it enabled them, for a time at least, to break, or at any rate crack, the narrow mould of Confucianism and arrive at a freer, more sophisticated kind of criticism.

The Liang dynasty which ruled in Nanking during the first half of the sixth century is an extreme example of the combination of political darkness and cultural splendour which characterizes this age. The history of its founder Xiao Yan and his numerous progeny reads like a Jacobean tragedy. Xiao Yan, betrayed by his own nephew to a foreign adventurer, died of hunger at the age of eighty-six, imprisoned after a siege of unprecedented awfulness in the course of which most of the inhabitants of Nanking lost their lives. His brilliant eldest son Xiao Tong having died many years previously as a result of a boating accident, the next eldest Xiao Gang was made puppet emperor by the conqueror, but deposed less than two years later in favour of Xiao Tong’s eldest son and shortly after pressed to death under sacks of earth. Xiao Gang’s ten sons were also put to death. His young nephew, the new puppet-emperor, and the young nephew’s two brothers were drowned by the deputy of another uncle when the latter recovered what remained of Nanking from the conqueror. And so on. It would be tedious to narrate the various violent ends which overtook the wicked uncle and the numerous other Liang princes. Murder and treachery so monotonously reiterated seem to belong to the annals of Roi Ubu [Note] rather than to serious human history.

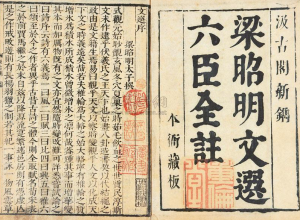

Yet if we turn from the political to the cultural history of the the time we find that Xiao Yan was both a devout Buddhist and one of the greatest ever patrons of Chinese Buddhism. He and Xiao Gang were accomplished poets and left quantities of verse which, if somewhat slight, is of very considerable charm. Xiao Gang’s protégé, the diplomat Xu Ling, compiled, at his suggestion, an anthology of lyric verse dating from the first century up to his own day (some eighty-odd poems by Xiao Gang are included in it). Xiao Tong, the Crown Prince, who died of a neglected chill at the age of thirty, complied a much larger, more ambitious anthology, including prose as well as poetry and ranging in time from the fourth century B.C. to the fifth century A.D., which still remains our principal source for the literature of half a millennium. In compiling this great anthology he may have been helped by Liu Xie, a Confucian who ended his days as a Buddhist monk and whose own Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons (literature to this Buddhist-Confucian was no childish hobby) is arguably the most important works of literary criticism in the Chinese language.

Later attitudes to the literary achievements of this age were somewhat ambivalent. It’s gongoristic, allusive, overwrought prose went out of fashion, and its poetry, particularly the ‘Palace Style’ favoured by Xiao Gang, came to be regarded as artificial, trivial and ‘decadent’. Yet poets of this period were admired by Du Fu and Li Bo, and all Tang poets were to some extent formally indebted to them. Xiao Tong’s anthology, the Wenxuan, remains to this day one of the first books that the student of Chinese literature has to invest in. During the Tang and Song dynasties (seventh to thirteenth centuries), when education was still liberal, a young man thoroughly familiar with the contents of Wenxuan was reckoned to be already half-way along the road leading to an official career.

Source

David Hawkes, ‘The Age of Exuberance’, collected in Classical, Modern and Humane, edited by John Minford and Siu-kit Wong, Hong Kong: The Chinese University Press, 1989, pp.306-308. This essay was originally a review of Wenxuan or Selections of Refined Literature: Volume One, Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals, translated by David R. Knechtges, Princeton University Press, 1982; and, New Songs from a Jade Terrace: An Anthology of Early Chinese Love Poetry, translated by Ann Birrell, Allen and Unwin, 1982, originally published in The Times Literary Supplement, 24 June. It is reprinted here with the permission of John Minford and the Hawkes Estate.