Duncan M. Campbell

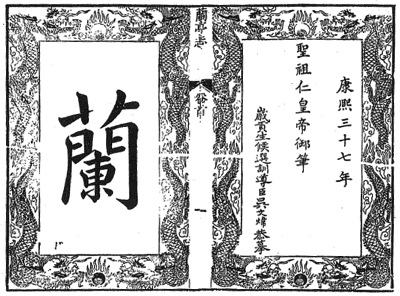

In an earlier issue of China Heritage Quarterly (Issue 17, March 2009), I discussed a proposed anthology of literary representations of Orchid Pavilion; this present translation contributes to this ongoing project by presenting for English readers a text written seventy-odd years earlier than the one translated in that issue.

Writing in 1597, shortly after visiting Orchid Pavilion in Guiji 會稽蘭亭, the late-Ming essayist Yuan Hongdao 袁宏道 (1568-1610) wrote a simple account of the celebrated site and its somewhat bleak present air:

How desolate Orchid Pavilion now appears! The Orchid Pavilion of antiquity was nestled within the hills and alongside a stream. With its many twists and turns, no more perfect spot for a meander along which our wine cups can float could possibly be imagined. At present, however, a channel has been dug out on a flat piece of land and a meander created. Such is the ignorance of the vulgar pedant 俗儒![1]

In a longer and revised version of his record, which he entitled ‘A Record of Orchid Pavilion’ 蘭亭記, Yuan engaged both with the site itself and with its fate, as well as with Wang Xizhi’s 王羲之 (309-ca. 365) ‘Preface’ to his own ‘Record of Orchid Pavilion’ 蘭亭記 of 353CE which created a mystique about the place that continued to beguile the imagination of men-of-letters so many centuries later:

Such has been the extent to which men-of-letters, from ancient times to now, have cherished the passing moment 愛念光景 that few of them have not sighed regretfully about the gulf that separates life from death. Thus on occasion have they climbed high and, looking out over the flowing waters, bemoaned the impermanence even of the hills and the valleys themselves; or, standing beside flowers at dawn or under the moon at dusk, sighed about the transience embodied in both the settling of a fall of dew and the flash of lightning. Although they may well find themselves in circumstances that bring both joy to their hearts and satisfy their fondest ambitions, nonetheless a deep-seated sense of anxiety always lurks within them and all the achievements and fame, wealth and honour that the world can offer are still insufficient to dissolve an unsettling sense of dissatisfaction. For this reason the base indulge in wine and singsong girls whilst the high-minded seek solace in brush and song pursuing immortality, or devote themselves to transcendence through the study of Buddhist and Taoist scripture. Their entanglements may be different, but their thirst for life and dread of death is a common bond. The vulgar and the foolish, however, are distracted by the meretricious surface of things and despite the evidence before their own eyes ignore the inevitability of death. And then there is the loathsome scholar who, prisoner of his own moralistic convictions, proclaims for all to hear: ‘Death is death; what is there to fear?’ Such men are ignorant in the extreme and are not worth further consideration. In his immense wisdom, Zhuangzi employed the metaphor of the hidden mountain;[2] although Confucius was a sage, he too sighed at the flow of the river.[3] Were death not something to be feared, then why was it that the sages of old placed so much importance upon hearing of the Way? 古今文士愛念光景,未嘗不感歎于死生之際。故或登高臨水,悲陵谷之不長; 花晨月夕,嗟露電之易逝。雖當快心適志之時,常若有一段隱憂埋伏胸中,世間功名富貴舉不足以消其牢騷不平之氣。於是卑者或縱情麯蘖,極意聲伎,高者或託為文章聲歌,以求不朽; 或究心仙佛與夫飛昇坐化之術。其事不同,其貪生畏死之心以也。獨庸夫俗子,耽心勢利,不信眼前有死。而一種腐儒,為道理所錮,亦云:「死郎死耳,何畏之有!」此其人皆庸下之極,無足言者。夫蒙莊達士,寄喻于藏山;尼父聖人,興歎于逝水。死如不可畏,聖賢亦何貴于聞道哉?

Wang Xizhi’s ‘Record of Orchid Pavilion’ 蘭亭記 is a profound meditation on life and death. Amongst the writings of the men of the Jin dynasty [265-420], such a work is a rarity and yet it was not included in Xiao Tong’s 蕭統 [501-531] Selections of Refined Literature 文選. Although later scholars of rhetoric have derided Wang for such formulaic expressions as ‘silk and bamboo, pipes and strings’ 絲竹管弦 and ‘the day was fine, the air was clear’ 天朗氣清,[4] such phrases do not detract at all from the sense of the piece, and should not be considered faults. 羲之蘭亭記,於死生之際,感歎尤深。晉人文字,如此者不可多得。昭明文選獨遺此篇,而後世學語之流,遂致疑于「絲竹管絃」「天朗氣清」之語,此等俱無關文理,不如於文何病?

Xiao Tong was a particularly vile scholar, as is evident from his ‘Preface’ to the Poems of Tao Qian in which he comments that the eroticism of the poet’s ‘Rhapsody on Stilling the Emotions’ 閒情賦 represents a tiny flaw in an otherwise perfect orb of white jade 白璧微瑕. After all, are not all men addicted to sex? Were this not true then I doubt that Confucius would have employed this predilection as a metaphor in the manner in which he did.[5] 昭明,文人之腐者,觀其以閑情賦為白璧徵瑕,其陋可知。夫世果有不好色之人哉? 若果有不好色之人,尼父亦不必借之以明不欺矣。

Orchid Pavilion is situated within a disorderly outcrop of hills. The stream there twists and turns; I suspect that this is the site where the ancients did indeed float their wine cups. At present, however, a channel has been dug on a flat piece of land and a meander created thereby. It is as though it is simply some feature to be found in some worthy’s garden.[6] 蘭亭在亂山中,澗水彎環詰曲,意古人流觴之地郎在于此。今擇平地砌小渠為之,與人家園亭中物何異哉!

Related material from China Heritage Quarterly

- Orchid Pavilion: An Anthology of Literary Representations, by Duncan M. Campbell

- The Family Studio of a Ci Poet, by John Minford and Soong Shu-kong

- ‘Black Tigers’ (hei laohu 黑老虎), by Duncan M. Campbell

Notes

[1] Qian Bocheng 錢伯城, ed., The Complete Works of Yuan Hongdao: Collected and Collated 袁宏道集箋校, Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe, 1981, vol.1, p.444. As in the past, I am most grateful for the comment made on an earlier draft of this translation by the editor, Geremie Barmé.

[2] This appears to be an allusion to ‘The Great and Venerable Teacher’ chapter 大宗師 of the Zhuangzi 莊子in which there is a discussion of the nature of life and death: ‘The True Man of ancient times knew nothing of loving life, he knew nothing of hating death. He emerged without delight; he went back in without a fuss.’ The specific reference to the hidden mountain comes in a passage that, again in Burton Watson’s translation, reads: ‘The Great Clod burdens me with form, labours me with life, eases me in old age, and rests me in death. So if I think well of my life, for the same reason I must think well of my death. You hide your boat in the ravine and your [mountain] in the swamp and tell yourself that they will be safe. But in the middle of the night a strong man shoulders them and carries them off, and in your stupidity you don’t know why it happened. You think you do right to hide little things in big ones, and yet they get away from you. But if you were to hide the world in the world, so that nothing could get away, this would be the final reality of the constancy of things.’ See, Burton Watson, trans., The Complete Works of Chuang Tzu, New York: Columbia University Press, 1968, pp.78 & 80-81. In his translation, Watson accepts a suggested Qing-dynasty emendation that gives ‘fish net’ for ‘mountain’.

[3] ‘The Master stood by a river and said: “Everything flows like this, without ceasing, day and night”,’ for which, see Simon Leys, trans., The Analects of Confucius, New York & London: W.W. Norton, 1997, p.41.

[4] For a discussion of this omission, see David R. Knechtges, trans., Wen Xuan or Selections of Refined Literature: Volume One: Rhapsodies on Metropolises and Capitals, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1982, p.42. Knechtges concludes that the most likely explanation may well be that, during Xiao Tong’s day, Wang Xizhi’s ‘Preface’ was simply unavailable. More generally on Orchid Pavilion, see Knechtges’s ‘Jingu and Lanting: Two (Or Three?) Jin Dynasty Gardens’, in Christoph Anderl and Halvor Eifring, eds, Studies in Chinese Language and Culture: Festschrift in Honor of Christoph Harbsmeir on the Occasion of His 60th Birthday, Oslo: Hermes Academic Publishing, 2006, pp.395-405, where he argues, convincingly, that both words of the usual translation ‘Orchid Pavilion’ are probably anachronistic.

[5] Again the Analects reads, in Leys’s translation: ‘The Master said, “I have never seen anyone who loved virtue as much as sex.” ‘ (p.41)

[6] Qian Bocheng, ed., Yuan Hongdao ji jianjiao, vol.1, pp.443-444.