Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium

Chapter XXIV, Part One

楓橋

The calendar of China bristles with anniversaries marking significant historical events and political moments. Every year is one of some significance and 2023 is no different. As part of our series Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, the year 2023 is particularly noteworthy. In the first place, it marks the seventieth anniversary of the ‘socialist transformation of the economy’, the devastating consequences of which are felt to this day. It is sixty years since the Chinese Communist Party formally declared ideological war on Soviet Revisionism in the form of the ‘Nine Critiques of the Soviet Communist Party’ 九評蘇共, as well as being six decades since the canonisation of Lei Feng (雷鋒, 1940-1962), a PLA soldier who is still held up as a paragon of unquestioning loyalty and obedience to the Communist Party. It is also the sixtieth anniversary of Mao Zedong’s promotion of ‘The Maple Bridge Experience’ 楓橋經驗, something that has profound significance for social management in Xi Jinping’s surveillance state.

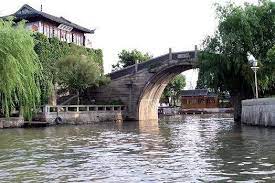

[Note: The Maple Bridge Experience, which was inspired by a series of harsh policies pursued by cadres in a township in Zhuji county in the early 1960s, should not be confused with the Maple Bridge of Suzhou immortalised in ‘Mooring at Night by Maple Bridge’ 楓橋夜泊, a poem by Zhang Ji 張繼 of the Tang dynasty.]

For decades, ‘Maple Bridge’ has shaped the Chinese party-state’s policies of social policing, surveillance and coercion, more popularly known as ‘stability maintenance’. Since 2003, Xi Jinping has demonstrated an enthusiasm for Maple Bridge that is on a par with his obsession with Jiao Yulu (焦裕祿, 1922-1964), the model Party cadre who had initially been promoted by Mao in 1964 and whose reputation was revived, first in 1990 and again in 2014.

The year 2023, also marks four decades since the Communist Party launched a three-pronged campaign to purge ideological liberalisation within the Party, to reject outside cultural influences within the society and to ‘strike hard’ against widespread criminal behaviour. Ever since, the Party’s approach has bundled together ideological control, cultural containment and law and order. Although its tripartite policies have often pursued in a haphazard fashion, under Xi Jinping a more unified approach has drawn the disparate threads of the past to weave a whole cloth. The effect is stifling. The consequences of that multifaceted moment were profound. Today China remains trapped in a vicious cycle of inhumanity that was clearly articulated by Communist Party leaders and theoreticians in 1983.

For me, the three-pronged campaign of 1983 further encouraged an approach to understanding contemporary China in terms of economics, politics, culture and social control. Eventually I would promote this multifaceted approach as New Sinology.

In celebrating the sixtieth anniversary of the Maple Bridge Experience in November 2023, Xi Jinping will again demonstrate his determination to link China’s Maoist past with its post-Mao reformist present.

***

In ‘The View from Maple Bridge’, a four-part chapter in Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, we consider the history of Maple Bridge and its abiding significance.

I am, as ever, grateful to Reader #1 for finding time to trudge through the draft of this material. All remaining errors are my own.

— Geremie R. Barmé

Editor, China Heritage

5 February 2023

Fifteenth Day of the First Month of the

Guimao Year of the Rabbit

癸卯兔年正月十五元宵節

***

Recommended Reading:

- The End of the Beginning 元宵, China Heritage, 11 February 2017

- You Should Look Back, the introduction to Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium, 1 February 2022

- Red Allure & The Crimson Blindfold, China Heritage, 13 July 2021

Contents

Click on a highlighted title to scroll down.

- Preface: What’s So Hard to Stomach?

- Upon First Crossing Maple Bridge

- Ah, Humanity!

- Alienation, Bolts, Nails and Huminerals

- Culture Clubbed: Dealing with China’s ‘Spiritual Pollution’

- A Man Misunderstood

- The Film Everyone Talked About but No One Ever Saw

- Just Another Thought?

- Making the Crime Fit the Punishment

- Public Pollutant No. 1

- China’s First ‘Non-Movement’

- The Last Word

- Further Reading

- Hu Muying’s Warning

***

A Guide for the Reader:

Following a note on contemporary events we discuss the origins of the Maple Bridge Experience. This is followed by revisiting the discussion of humanism in China in the early 1980s in which we draw on work from Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience (1986). The remainder consists features an essay written in late 1983 and published in January 1984 on the joint Strike Hard and Spiritual Pollution Campaign. We conclude with a short bibliography.

***

What’s So Hard to Stomach?

On 14 January 2023, Jiang Yunzhong, a leading educator and senior party official at Tsinghua University, used his social media account to comment on the impact of the government’s post-zero-Covid policy u-turn:

I’ve repeatedly done the sums over the last six months, so in the wake of opening up I was psychologically prepared to see a few million deaths. In retrospect, and as the epidemic approaches its denouement, I’d point out that not all that many have actually died. In fact, the numbers are entirely within acceptable parameters and they certainly won’t be in the millions. This is not blind self-confidence, I’m speaking on the basis of facts. My observation is based on the figures that I have to hand at present. Then again, so what if a few million died? Ten million people died in China in 2021. If you add another five million to the total it would still only be an increase of fifty percent. That’s to say, instead of two people having died, three had died. The death rate hasn’t increased exponentially. What’s so hard to stomach?

等比例計算,這半年我已經演算過多次了,早就做好了放開後死幾百萬人的準備。只是這波疫情接近尾聲後回過頭來看,死的人並不是很多,還在可以接受的範圍之內,也不會出現死幾百萬這樣的情況了。我是根據我掌握的數據說話的。這不是什麼自信,而是實際情況。話說回來,就算死幾百萬人又怎麼樣?中國 2021年死了1000萬,再多死500萬,也就是增加了50%的死亡人數,就是原來死2個,現在死3個的區別,死亡率並沒有成倍提高。為什麼不能接受呢?

Jiang’s post sparked an online furore and Internet censors quickly moved to shut down debate about a man who was being widely decried as inhumane ‘scum’ 人渣 rénzhā. For many, Jiang’s heartless calculation was a reminder of an observation made by Li Yi 李毅, a leading proponent of the forced integration of Taiwan with the People’s Republic of China. During a public lecture in October 2020, Li remarked that: ‘If you compare the 4000 who have died [from the coronavirus] in Wuhan to the 22,000 dead in the United States, it’s the equivalent of no one having died at all 武漢死了4000千人與美國22萬的死亡人數相比,等於一個人都沒死.’ (See 北京鷹派學者李毅口出狂言 學者批狐假虎威,亞洲自由電台,2020年11月27日.)

We preface The View from the Bridge with this anecdote because Jiang Yunzhong offers a fortuitous matrix of connections that are relevant to our discussion. Jiang is a native of Zhuji county, Zhejiang province 浙江省諸暨縣, homeland of the Maple Bridge experience (Zhuji became a directly administered provincial city in 1989) and he was born in September 1963, two months shy of Mao Zedong penning a rescript that made Maple Bridge a national model for local policing and surveillance.

Jiang Yunzhong boasts another connection to our topic. Readers of China Heritage will recall the extended note on Maple Bridge in our translation of Xu Zhangrun’s essay And Teachers, Then? They Just Do Their Thing!

(China Heritage, 10 November 2018). As the party secretary of Tsinghua University Library, Jiang Yunzhong is also charged with the ‘moral edification’ 德育 déyù of the student body of that university. In that dual capacity, Jiang personally signed off on the removal of all books and articles by, as well as references to, Xu Zhangrun from the university’s sprawling library network.

[Note: Jiang Yunzhong shares a hometown with a far more notorious Party thug: Yao Wenyuan 姚文元, of Gang of Four fame.]

Upon First Crossing Maple Bridge

It is nearly fifty years since I first saw that faded slogan on a wall of a communal pig sty: ‘Learn from the Experiences of Maple Bridge’ 學習楓橋經驗, or ‘copy the Maple Bridge model’. Large white characters were imposed on a red background. It was only one of the slogans on walls in the village where, in the early summer of 1975, my class of foreign exchange students at Fudan University in Shanghai doing a stint of working with farmers at a People’s Commune in Minhang as part of a program of ‘open door schooling’. Other slogans exhorted villagers to ‘Learn from Dazhai Commune in Agriculture’, ‘Study the Daqing Oilfields’, ‘Celebrate the May Seventh Road for Cadres’ and, above all, ‘Be on Constant Alert to Defend the Fatherland’.

Minhang 閔行 was home to the first people’s commune that had been established in greater Shanghai at the height of the move towards radical communisation during the Great Leap Forward in the late 1950s. The village, or production brigade, to which we had been allocated was a model of political rectitude, safe for a group of bourgeois exchange students from Australia, France and Britain. Regardless of the cloud of officialdom that hung over us, the local farmers and their families went out of their way to be welcoming and they tolerated our clumsy attempts at planting paddy rice with unfailing good humour.

I asked about the Maple Bridge Experience and was given the shorthand account that the local cadres knew by rote. It was a policy covering governance in the context of the ongoing class struggle: keep a close eye on class enemies and disruptive elements, resolve policing issues locally rather than inviting outside intervention and put a cap on the number of people being jailed or executed for misdemeanors. Without reference works or detailed accounts of the Mao era in either Chinese or English available, I would only gradually piece together an understanding of Maple Bridge for myself.

Starting in the summer of 1977, I had a job in Hong Kong that entailed reading the official Chinese press and, one day late that year I noticed an article in the People’s Daily titled ‘Raise high the red flag of Maple Bridge set up by Chairman Mao and rely on the masses to strengthen the dictatorship of the proletariat’ 高舉毛主席樹立的楓橋紅旗 依靠群眾加強專政. During the three-pronged purge of 1983 I had learned enough about Maple Bridge to see the shadow that it continued to cast over contemporary Chinese life and I have appreciated the lasting effect it has had on Chinese politics, thought and society ever since.

***

***

Remembering Maple Bridge 楓橋經驗

Following the Great Leap Forward period (1958-1962), during which Mao’s misguided economic policies (again, all supported by the majority of his colleagues) effectively led to unprecedented mass murder through starvation and dislocation, the Chairman was forced to reassess his position. Sidelined by comrades who were anxious to salvage the Party amidst the unprecedented suffering they had engineered, Mao continued to plan a utopian future for China, one that would require him to take complete control of the party-state.

In late 1962, Mao began reasserting his ideological control by having the Party reaffirm his policy of ceaseless and uncompromising class struggle, discussed here. This was summed up at the Tenth Plenum of the Eight Party Congress in September 1962 at which the Party issued a call to the nation to ‘Never Forget Class Struggle’ 千萬不要忘記階級鬥爭. At that meeting Mao denounced ideological backsliding that supported such things as ‘the fashion of individual enterprise’ 單干風, the ‘move to overturn verdicts’ 翻案風 (about the Rightist Movement and the Great Leap) and ‘the negative talk about China having entered an era of darkness’ 黑暗風. Mao went on to tell his comrades that:

We must acknowledge that classes will continue to exist for a long time. We must also acknowledge the existence of a struggle of class against class, and admit the possibility of the restoration of reactionary classes. We must raise our vigilance and properly educate our youth as well as the cadres, the masses and the middle- and basic-level cadres. Old cadres must also study these problems and be educated. Otherwise a country like ours can still move towards its opposite. Even to move towards its opposite would not matter too much because there would still be the negation of the negation, and afterwards we might move towards our opposite yet again. If our children’s generation go in for revisionism and move towards their opposite, so that although they still nominally have socialism it is in fact capitalism, then our grandsons will certainly rise up in revolt and overthrow their fathers, because the masses will not be satisfied. Therefore, from now on we must talk about this every year, every month, every day. We will talk about it at congresses, at Party delegate conferences, at plenums, at every meeting we hold, so that we have a more enlightened Marxist-Leninist line on the problem.

要承認階級長期存在,承認階級與階級鬥爭,反動階級可能復辟。要提高警惕,要好好教育青年人,教育於部,教育群眾,教育中層和基層幹部,老幹部也要研究,教育。不然,我們這樣的國家還會走向反面。走向反面也沒有什麼要緊,還要來個否定的否定,以後又會走向反面。如果我們的兒子一代搞修正主義,走向反面,雖然名為社會主義,實際是資本主義,我們的孫子肯定會起來暴動的,推翻他們的老子,因為群眾不滿意。所以我們從現在起就必須年年講,月月講,天天講,開大會講,開黨代會講,開全會講,開一次會就講,使我們對這個問題有一條比較清醒的馬克思列寧主義的路線。

— from Mao Zedong, Speech at the Tenth Plenum of the

Eighth Central Committee, 24 September 1962

毛澤東在八屆十中全會上的講話[Note: During this notorious speech Mao avoided taking any real responsibility for the disaster of the Great Leap and, among other things, repeated one of the deathless lines of his rule:

On the question of work, comrades will please take care that the class struggle does not interfere with our work. The first Lushan Conference of 1959 was originally concerned with work. Then up jumped Peng Dehuai and said: ‘You fucked my mother for forty days, can’t I fuck your mother for twenty days?’ All this fucking messed up the conference and the work was affected. Twenty days was not long enough and we abandoned the question of work. 工作問題,還請同志們注意,階級鬥爭不要影響了我們的工作。一九五九年第一次廬山會議本來是搞工作的,後來出了彭德懷,說:「你操了我四十天娘,我操你二十天娘不行?」這一操,就被擾亂了,工作受到影響。二十天還不夠,我們把工作丟了。]

The emphasis on class struggle was part of a general push to affirm the importance role that political conflict had to play in advancing the Party’s agenda, which placed heightened ideological awareness and purity over the livelihood and welfare of normal people. This ‘lurch to the left’ was, among other things, encapsulated in late 1963 in what Mao celebrated as ‘The Practices of Maple Bridge’ 楓橋經驗, which had been developed at Maple Bridge township in Zhuji county, Zhejiang province 浙江省諸暨縣楓橋鎮.

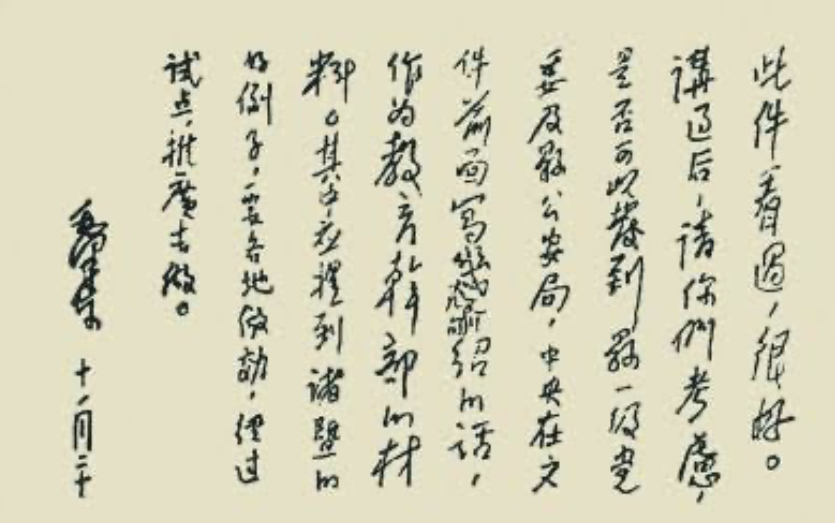

The Maple Bridge model was developed by the cadres of the township in the wake of the economic collapse of the Great Leap Forward. With limited policing resources, widespread dislocation and an impoverished population, local Party rulers developed a system of social control and repression that did not place an undue economic or administrative burden on the state. In particular, it prevented people who were in dire straits due to the Party’s economic mismanagement from protesting outside their own townships, or lodging complaints with those further up the chain of command. What was in fact a form of mutual surveillance, mass dictatorship, repression and radical social stability was summed up in the formula ‘mobilise and rely on the masses, resolve local problems without recourse to higher authorities and ensure that arrests are limited and social stability assured’ 發動和依靠群眾,堅持矛盾不上交,就地解決。實現捕人少,治安好. Supported by Xie Fuzhi (謝富治, 1909-1972), the ultra hardline Minister of Public Security, and Peng Zhen (彭真, 1902-1997), the architect of the purges and extra-judicial mass murders of the 1950s, the ‘Maple Bridge Experience’ 枫橋經驗 was endorsed by Mao, the architect of China’s rural catastrophe, in late 1963. He issued a rescript that read: ‘All local areas are to emulate [Maple Bridge], and after model areas have been consolidated the system should be launched nationwide’ 要各地仿效,經過試點,推廣去做.

The Practices of Maple Bridge helped create the basis for the ‘mass dictatorship’ during the Cultural Revolution era in the wake of the collapse of local party-state law and order bodies. Maple Bridge was reaffirmed after Mao’s death and it contributed directly to the Deng era policies of ‘Stability and Unity’ 安定團結, the practice of which evolved into the Stability Maintenance 維穩 policies of the new millennium. Maple Bridge also helped the Party formulate its repressive actions in Tibet in 1988 and 2008, and again, more recently, in Xinjiang.

In November 2003, when he was Party Secretary of Zhejiang province, home to ‘The Practices of Maple Bridge’, Xi Jinping extolled these repressive policies on the fortieth anniversary of Mao’s 1963 rescript. At that time, Xi said people must be mindful of the fact that Party policy not only champions the idea that ‘Economic Development is an Unbending Principle’ 發展是硬道理 but also that ‘Stability is an Unwavering Duty’ 穩定是硬任務. Maple Bridge was the backbone of the Peaceful Beijing Action Plan overseen by Xi Jinping during the 2008 Olympic year. On the fiftieth anniversary of Mao’s rescript in November 2013, Xi Jinping, now head of China’s party-state-army, enjoined the nation to study, enhance and expand ‘The Practices of Maple Bridge’ in order to ensure longterm social cohesion and stability.

Maple Bridge was reaffirmed yet again in November 2018, on the fifty-fifth anniversary of Mao’s rescript and it also featured in April 2020 during the first wave of the coronavirus epidemic. At the time, Xi Jinping re-iterated the importance of the Maple Bridge Experience in dealing with local governance, security and unemployment.

— see To Summon a Wandering Soul, China Heritage, 28 November 2018

Ah, Humanity!

In 1983, I was able to make sense of the three-part purge of ideas, culture and crime by recalling what I had learned about the Marxist-Leninist analysis of human nature and humanity when studying at Maoist universities in the 1970s. One of my classmates had been obsessed with the topic and at his suggestion I had read the texts that he recommended. Thanks to our classes in the ideological and cultural struggles that had riven the Chinese world since the 1920s, I was also able to follow the thread of debates concerning human nature from the 1940s. It is a long and tortuous tale summed up succinctly by Simon Leys who observed that:

… the Thoughts of Mao Zedong did present genuine originality and dared to tread a ground where Stalin himself had not ventured: Mao explicitly denounced the concept of a universal humanity; whereas the Soviet tyrant merely practiced inhumanity, Mao gave it a theoretical foundation, expounding the notion—without parallel in the other Communist countries of the world—that the proletariat alone is fully endowed with human nature. To deny the humanity of other people is the very essence of terrorism; millions of Chinese were soon to measure the actual implications of this philosophy.

From 1949 to 1978, humanism had been equated with a reactionary bourgeois worldview that threatened the very basis of Party rule. The unravelling of Maoism from the late 1970s was, at its core, an undoing of the Party’s view of class, class struggle, as well as of humanity and human nature. Over the five years from 1978 to 1983, the old debate about humanism and abstract human value was revisited.

In early 1979, Reading 讀書, the leading journal for liberal ideas published There Are No Forbidden Zones for Readers by Li Honglin 李洪林, a progressive Party ideologue who, with his comrades agitated for a reconsideration of humanism (Li was also opposed to hard liners like Hu Qiaomu who eventually won the ideological battle of the 1980s). The best-selling 1980 novel Ah, Humanity! by the Shanghai novelist Dai Houying 戴厚英 gave popular expression to ideas that were also been discussed in more theoretical terms, including, for example, ‘It’s High Time that the Sun of Humanity can Shine’ 人的太陽必然升起, a famously influential essay by Li Yihong 李以紅 published in February 1981.

To this day, despite contemporary rhetorical flourishes, the Communist Party’s evaluation of humanity and the crude materialism that is the bedrock of official ideology maintains that while the Party represents the People and their collective interests, people as individuals have no significant abstract value. The People represent an idea and an ideal; the individual is discounted.

— GRB

***

The Rebirth of My Humanity

Dai Houying

Twenty years ago I graduated from the East China Normal University in Shanghai ahead of my class, to begin a career in the tumultuous and disaster-ridden world of the Chinese arts. Blind faith and ignorance emboldened me, gave me a sense of confidence and power. I thought I had grasped the basic principles of Marxism and Leninism; I believed I had a correct understanding of society and of my fellow man. I stood up at the lectern in the university and declaimed a speech that had been painstakingly composed in accordance with the wishes of the leadership. In it I denounced my teacher’s lectures on humanism. “I love my teacher,” I announced to the world. “But I love the truth even more!” I felt intoxicated by the waves of enthusiastic applause that greeted these words; I felt proud to have become a “fighter” for the cause.

Now, twenty years later, I am writing novels. And in my novels I try to propagate the very things I so energetically decried in the past. I want to give voice to the concept of humanity in my writing, even though this is just the thing that I tried so hard to suppress and reform in myself. This is the great irony of my life.

A philosopher could sum up the change I have experienced in one simple statement: I have completed the circle of negating the negation. I am no philosopher, however, merely an average individual possessed of quite unremarkable faculties. In all of this I see the workings of fate. For I have witnessed the fate of China, her people, my loved ones, my own individual destiny. It is a fate full of blood and tears, and its meaning resounds with pain. But in it I see traced the tortuous path travelled by a whole generation of intellectuals. And such a weary and treacherous journey it has been!

When I was young, I was warm-hearted and simple-minded. All I ever thought of was the love I felt for the Party and for New China. I knew that I must study hard and serve the people. I was absolutely sincere in my devotion to the Party and socialism. This was because Liberation had provided me with the chance of a university education, a privilege that no one in my family had been able to enjoy. I was the first woman in my family to have an education, and to my young and ardent heart socialism and communism were a world of wonder and excitement. I honestly believed that our cause was just, that our future was bright and that the way ahead was clear and smooth. I didn’t have a care in the world, I was completely unselfconscious, entirely without fear. My heart brimmed over with warmth and love.

In 1957 the concept of “class struggle” was encoded in my brain. In 1966 a new programme was added to it: that of “line struggle”.

I did my best to see everything in terms of these two “struggles”. I was as involved in the front-line assault during the “big criticism” campaigns of the early Cultural Revolution: I was a “rebel soldier” under the command of the Red General. At one time I quite piously believed that everything in the world was a question of class struggle. We had to keep class struggle in mind every waking moment.

But despite all this I was still a human being. I had not been completely numbed. I too felt the tribulations of life. I could see the bloody wounds on people’s bodies, the tears on their faces. I too felt pangs of conscience. I was mindful of the cries that issued from the depths of my soul. And often I would ask in my heart of hearts: Isn’t our struggle too extreme? Haven’t we wronged innocent people? Was it really necessary to carry out class and line struggle every minute of every day throughout the breadth and width of China?

As the movement to repudiate the Gang of Four continued I came to realize many things I had not known or could not have imagined in my wildest dreams. I was shocked to the very core of my being when it finally dawned on me that the God I had enshrined in my mind was tumbling, and that the pillars of my faith were about to collapse. Nothing made sense any more. I would often sit in a dazed stupor, burst into tears for no reason or start shouting hysterically. How I wished I could take hold of the God I had worshipped for so long, and all those other deities I believed in, and give them a good shake. I wanted to ask them: Is all of this true? Why did you tell us such a different story? Did you deceive us on purpose or was it really a “process of recognition” for you too? For a time I wandered lost in the night of my soul.

Then I began to reflect, looking deep into myself as I bandaged my bleeding wounds. I read through the diary of my life page by page, straining to make out the footprints that trailed off into the lost distance of my own past.

Eventually, I came to see that I had been playing the role of a tragic dupe in what was a mammoth farce. I was a simpleton who believed herself to be the freest creature on earth, when in fact I had been robbed of the right to think. The cangue that weighed heavy on my soul had always seemed to me a beautiful garland of flowers. I had lived out half my life without having come to any understanding of myself.

I wrestled free of that role and went in search of myself. So I too was mere flesh and blood; I too could love and hate like other people; I too was possessed of all the feelings and passions of man, and I too could think for myself. I knew I had a right to believe in myself and to have a sense of my own worth, that I shouldn’t allow myself to be manipulated or made into some “submissive tool”.

Gradually a word written in blazing capitals shone before my eyes. That word was HUMANITY: The words to a much-maligned and long-forgotten song welled up in my throat: Humanity, Human Feelings, Humanism.

It was as though I had woken from a dream. Even though the cold sweat of night was still damp on my flesh and my mind was still groggy, nonetheless, I was finally awake. I wanted to tell the world that I was now a conscious human being. So I started to write . … The theme of all my works is Man. I write of the caked blood, the welling tears, the twisted souls and the agonized cries. I write of the spark of light that shines in the abyss of darkness. I cry out at the top of my voice: “You may return, oh soul; here is your home!” And I record with joy the rebirth of my humanity.

from the postscript to the novel Humanity!

August 1980, Canton

An Incorrect Interpretation of Life

The author of Humanity! has failed to interpret life accurately, and is unable to draw correct conclusions based on an overall world-view. It is quite clear from this novel that she has ignored the main political trends in China since the Gang of Four. She misleads her readers with vacuous humanistic sermonizing, as if humanism were the ideal cure-all for the ills of the age.

Obviously the author of Humanity! has tried to create in the character He Jingfu a humanistic saviour alienated from the mainstream of political life. She wishes to offer us one possible model for the future. But in doing this, she has omitted many elements which are essential for a complete and accurate picture of reality. The main forces of resistance during the Cultural Revolution — those cadres and common people who fought persistently against the erroneous line are left out of the picture: instead the foreground is occupied by this image of an idealized humanist. We can learn from this that if writers are unable to interpret life correctly, they will also be unable to describe it accurately, and thus will fail to embody its essential reality in their works.

Literary Gazette, May 1982

— from Geremie Barmé and John Minford, eds, Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, Far Eastern Economic Review: Hong Kong, 1986, pp.157-160

[Note: I met Dai Houying at a literary gathering in Shanghai in late 1986, shortly after Seeds of Fire appeared. We maintained irregular contact until the time of her murder in 1996.]

***

Alienation, Bolts, Nails and Huminerals

Above we noted that the year 2023 also marks the sixtieth anniversary of Mao’s exhortation to ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng’, a model PLA soldier and faithful student of Mao Thought. In our study of ‘Huminerals’ 人礦 — the exploitable masses of ‘shitizens’ 屁民 — we observed that ‘The Bolt Spirit’ 螺絲釘精神 (‘I am a willing bolt in the machinery of the nation’) exemplified by Lei Feng holds little mass appeal. Still, the Party enjoins the nation to emulate Lei Feng just as Xi Jinping repeatedly instructs Party members to work tirelessly in ‘the spirit of hammering nails’ 釘釘子精神.

[Note: To mark the twentieth anniversary of Mao’s 1963 call to study Lei Feng, in 1983 the Party declared that the nation had to ‘Learn from Comrade Lei Feng and nurture Communist ethics’ 向雷鋒同志學習,培養共產主義品德. Zhu Boru (朱伯儒, 1938-2015), a tireless PLA do-gooder, was declared to be a ‘living Lei Feng’.]

Be they as the bolts of Lei Feng or the nails of Xi Jinping, individuals are primarily seen as having a utilitarian value, a view of human worth that has been at the core of the Communist Party’s enterprise from the 1930s.

[Note: See Xi Jinping’s Harvest — from reaping Garlic Chives to exploiting Huminerals, 6 January 2023]

— GRB

***

Socialist Humanism

Wang Ruoshui

A spectre is haunting the Chinese intellectual world — the spectre of humanism. I wish to come to the defense of humanism in general, and especially of Marxist humanism. In the present period, when we are constructing socialism and modernizing our country, we need socialist humanism. What are the implications of this humanism for us?

— It means the determined rejection of the “total dictatorship” and cruel struggles of the Cultural Revolution; the abandonment of personality cults which deify one man and degrade the people; the upholding of the equality of all before truth and the law; and the sanctity of personal freedom and dignity.

— It means opposing feudal ranks and concepts of privilege, opposing capitalism, the worship of money, and the treatment of people as commodities or mere instruments; demanding that people should really be seen as people, and that individuals should be judged by what they are in themselves, and not on the basis of class origin, position or wealth.

— It means recognition that man is the goal not only of socialist production but of all work. We must establish and develop mutual respect, mutual loving care, and mutual help embodying socialist spiritual civilization; and we must oppose callous bureaucracy and extreme individualism, both of which cause harm to others.

— It means valuing the human factor in socialist construction; giving full play to the self-motivation and creativity of the working people; valuing education, the nurturing of talent and the all-round development of man. …

Is this socialist humanism not already to be found in our practice? Is it not growing around us from day to day? Why treat it as something strange, something alien?

A spectre haunts the intellectual world:

“Who are you?”

“I am Man.”

***

Humanist Poison

Hu Qiaomu

Sloganeering about humanism will only encourage all kinds of unrealistic demands for individual well-being and freedom, and create a false impression that once the socialist system is established, all personal demands will be satisfied — for otherwise, the socialist system would be proven “inhumane”. …

Some of those who preach humanism have set the value of the individual against the development of the cause of socialist construction, and have even alleged that the “human world continues to deteriorate, while the material world (including authority) continues to gather strength.”

— from On Humanism & Alienation, January 1984

— both of these excerpts are from Seeds of Fire, pp.150-151

***

[Note: For more on Hu Qiaomu’s role in modern Chinese history, see Ruling The Rivers & Mountains, China Heritage, 8 August 2018.]

Culture Clubbed, 1983, 2023

Re-introducing a Period Piece

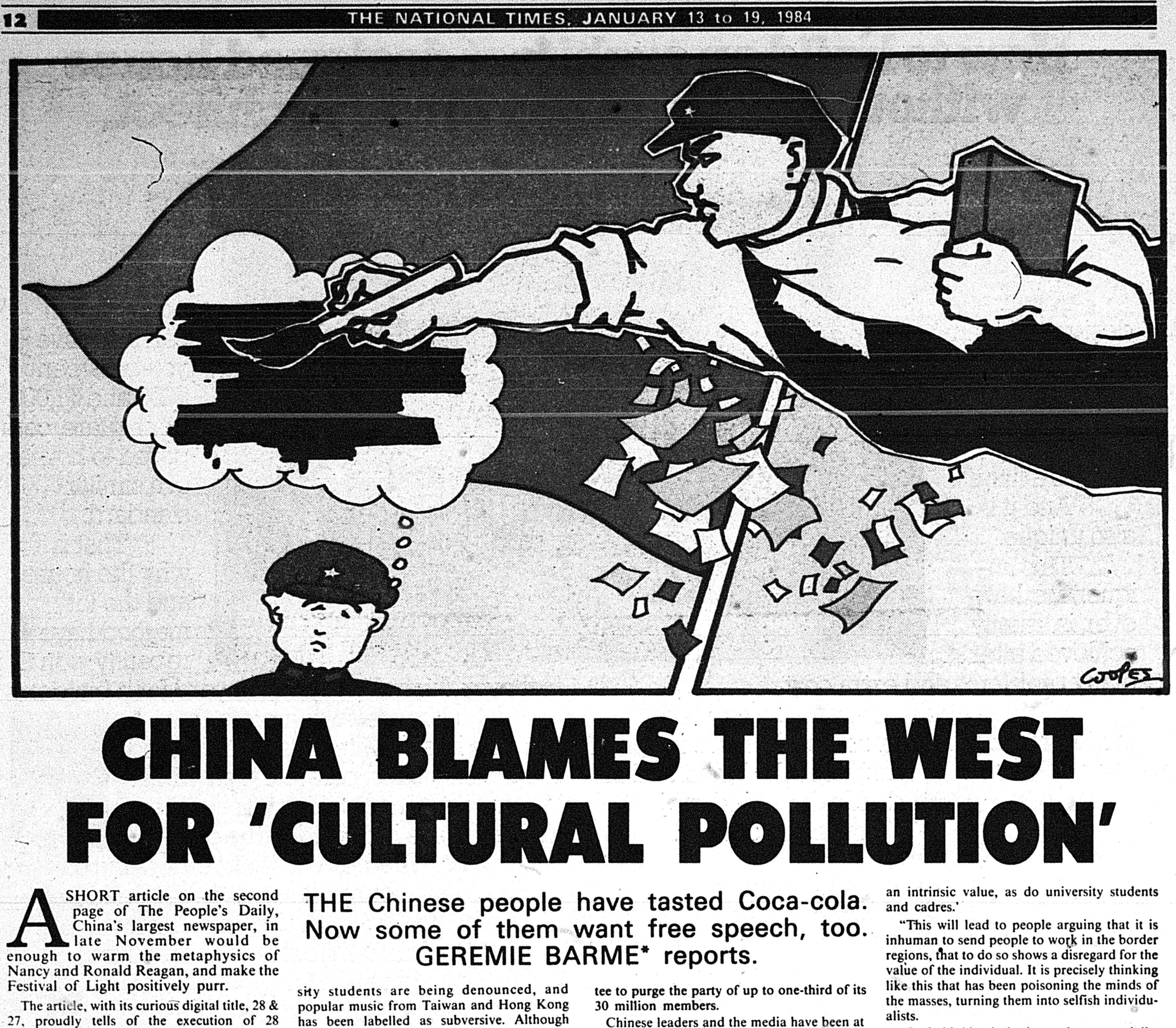

The following essay, written in November 1983, appeared in the Australian weekly The National Times in January 1984 under the title ‘China Blames the West for “Cultural Pollution” ’. It was reprinted under the titled ‘Spiritual Pollution Thirty Years On’ in The China Story Journal on 17 November 2013 and subsequently reprinted in China Heritage as a chapter in Watching China Watching.

At the time the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign 清除精神污染運動 was dismissed by many people both in China and internationally as being mere hiccup, a moment of backsliding in the unfolding process of reform and liberalisation that had little deeper significance. While the ‘Strike Hard’ crackdown on crime would continue for years, the formal ideological purge of ‘spiritual pollution’ petered out after a few months. It turned out that Party leaders were concerned that the ‘ideological red noise’ might distract from their overall reformist strategy.

[Note: For a study of the Strike Hard campaign of 1983-1986 and how it provided a template for subsequent policing activities, see Susan Trevaskes, Policing Serious Crime in China: From ‘strike hard’ to ‘kill fewer’, London and New York: Routledge, 2010, chapter 2.]

In reality, 1983 was an extension of Deng Xiaoping’s attack on ‘bourgeois liberalisation’ 資產階級自由化 in March 1979. Just like the mass campaigns of the Mao era, both the 1979 mini-purge and the movement of 1983 combined an ideological framework with a hardline rejection of non-Party cultural values and behaviour which was pursued in tandem with a crackdown on crime.

When my essay on the Anti-Spiritual Pollution Campaign appeared, I was derided both in China and overseas by those who regarded that, in the context of the ‘larger picture’ of China’s economic reforms and the presumed inevitability of ongoing positive political and cultural change, the 1983 attack on Western values, humanism and non-Party controlled culture was little more than a minor irritant.

My experiences as a student in China and as an editor in Hong Kong working with Lee Yee, and as a columnist in the Chinese language press in Hong Kong, as well as the influence of my mentor Simon Leys and the friendships of many who had suffered through the Maoist years, had taught me to be skeptical about mainstream opinion, the liberal aspirations of people in China and the media. As the 1980s unfolded, I followed the activities of hardline ideologues like Hu Qiaomu and Deng Liqun as well as those of their younger acolytes. I took them seriously, as I did Deng Xiaoping’s refusal in 1978 to revisit the calamity of the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957, or indeed many of the ‘cultural wars’ of the 1950s. They formed part of the bedrock of the state: be it the dispossession of the capitalists, the bourgeoisie, business owners and farmers; the extreme patriotism of the Korean War period; the radical rejection of the possibility of political reform; or the numerous thought reform campaigns. Deng himself remarked that they had done under Mao’s leadership from 1949 to 1958 was essentially correct. Those who failed to take that statement seriously — and they were in the majority — simply misunderstood the basic orientation of Communist Party rule during the reform era.

For me, the 1983 cultural and policing purge set the stage for the future: be it 1987, or 1989. It highlighted the fundamental nexus in Communist Party thinking between ideology, civil control, policing and cultural conservatism. Even during the most freewheeling and open phases of China’s post-Mao reform era, the Party’s struggle with Western liberal values, peaceful evolution and cultural contamination, the origins of which date back to 1948, has continued. Now, in 2023, the historically purblind continue to think that the Xi Jinping era represents a break with the past rather than its continuation.

It is in this context that the year 2023 marks another anniversary, that of the Southern Weekly incident of January 2013 when the topic of constitutionalism 憲政, a shorthand for placing legally binding limits on the Party’s power, was banned from public discussion.

— GRB, February 2023

***

Culture Clubbed:

Dealing with China’s ‘Spiritual Pollution’

Geremie Barmé

He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils.

—Francis Bacon, The New Atlantis

A Man Misunderstood

A short article secreted on the second page of the People’s Daily, China’s largest newspaper, in late November [1983] would be enough to warm the metaphysics of Nancy and Ronnie Reagan, and possibly make the Festival of Light include China in their hit-list of salvation.

The article with its curious digital title ‘28 & 27’ proudly tells of the execution of twenty-eight criminals in Fuzhou city, South China. Twenty-seven of those executed began their short slide into the abyss of perdition after having watched pornographic video tapes. One particular Production Brigade in Changle District, we are told, became a seething nest of adolescent rapists, prostitutes and robbers following the screening of porn movies over a number of nights. ‘This kind of spiritual opium undermines morals, pollutes the atmosphere and poisons the minds of the young’, the paper comments in a mood of high dudgeon.

For Chinese readers the word ‘opium’ is redolent of dark and humiliating associations, and playing on this the article goes on to remind us of the valiant action of the Imperial Commissioner Lin Zexu who, some 140 years ago, destroyed British stores of opium in Canton, thereby saving a lucky few of his fellow countrymen from certain degradation. The paper continues that present-day cultural opiates and their purveyors must be wiped out in the nationalistic spirit of Commissioner Lin.

The tone, style and even the overused historical allusions of this piece are only all too familiar to readers of the Chinese press, recalling as they do the bombastic overstated diction of Cultural Revolution propaganda. The Chinese media has been awash with such stories over the last six weeks as the country enters yet another confusing period of intellectual and cultural backtracking, this time it is a new and decisive step in the Communist Party’s protracted struggle against ‘spiritual pollution’. Although generally referred to as a new political purge in the Western press, this ‘exercise in cleaning up cultural contamination’, as one skilful translator puts it, is actually an ideological snowball that was set rolling as early as March 1979, by none other than China’s new helmsman, Deng Xiaoping.

Speeches and editorials that have appeared over the weeks warn of the need for a national effort to put an end to the complaisant and permissive attitude towards ideological deviation, cultural liberalism and the popular decadence and vulgarity that have resulted from opening up to the West. The woeful decline in Party prestige and morality is being blamed partly on the ‘impure elements’ who managed to infiltrate the ranks of the Party organization during the Cultural Revolution, but on the whole, the rampant individualism and the growth of a crude and unwholesome petit-bourgeois mass culture throughout the country is seen as being Western in origin.

Writers like Kafka and Sartre who have a tremendous following among Chinese university students are being denounced, and popular music from Taiwan and Hong Kong has been labeled subversive. Although foreigners are assured that the xenophobic attacks on Western music, fashions, literature and philosophy are not meant as a negation of Western culture in its entirety, the tenor of official pronouncements amounts to nothing less than the tired old equation that, Western = bourgeois = decadent = anti-socialist. One of the most intriguing, and to my mind persistently ignored factors of the situation in China at the present is the burgeoning class of nouveau riche farmers and city dwellers born of the new government policies that give official backing to a myriad of ‘get rich quick’ schemes for the masses, and the partial introduction of a free market economy. This is a class that is fast learning about extravagant and highly un-proletarian habits of the well-to-do, and along with an ever-increasing population of young educated sophisticates, there is an insatiable demand for a rich and varied cultural life. In a buyer’s market how can you effectively legislate against consumerism? Not surprisingly, rather than pointing the finger at their own daring economic policies, the leaders of the Communist Party have opted for the familiar and oft-used tack of dumping on the bourgeois West.

Present government concern for the wrong-headed fripperies of the masses can be traced back to the end of 1978. At that time, thousands of young people, robbed of an education, a future and their ideals in the Cultural Revolution, went into the streets of China’s major cities to agitate for the resignation of certain Party leaders, a new deal for themselves and democratic reforms. Deng Xiaoping, who was then still tussling to ensure his supremacy in the government, at first encouraged these wild demonstrations. But once his major ‘leftist’ opponents had been cowed into silence not long after, Deng, a brilliant political strategist who had even outwitted the dangerously mercurial Mao Zedong, divested himself of these young supporters. Bringing an end to the Democracy Wall in Beijing, he authorized the arrest of dozens of dissidents, especially as they were becoming increasingly critical of him and threatening the delicate balance of power within the Politburo.

Certainly, Deng had been behind the call in the press for people to ‘use your brains and liberate your thinking’, but that meant cadres should shake themselves free of the Maoist line of the Cultural Revolution. The last thing he had wanted was that willful young people would start questioning the authority of the Communist Party and go so far as to call on Jimmy Carter to support the cause of human rights in China. Enough was enough, and in March 1979, Deng made a withering speech on the ‘principle of the four sticks’ [四个坚持], in which he made it obligatory for everyone in the country to stick to: the socialist road; the dictatorship of the proletariat; the leadership of the Communist Party; and, to Marxism, Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought.That speech and its catechetical formulation of the ‘four sticks’ has become the basis for the new Chinese political orthodoxy, and the present attack on ‘spiritual pollution’ and the purge of dissenting Party members stem directly from it.

It is surely with a sense of irony that we look back at those early reports on the pragmatist hero Deng Xiaoping. In 1979 and 1980, foreign leaders and journalists alike were falling over themselves in the rush to heap laurels at Deng’s feet. We admired him not so much perhaps for his open-minded humanity in guiding China out of two decades of disasters, but more out of gratitude for his willingness to let foreign capital into China once more, to open the country’s potentially vast market to Western goods.

The newspaper photographs seem to have preserved the mood of the time better than any single written report: a shot of Mao-suited bureaucrats disco-dancing with American diplomats to celebrate the normalization of relations; beauty salons in Shanghai in which women, and even men, happily consented to having their hair linked up to electrical ganglia to get a permanent wave; young demagogues in the streets of Beijing addressing crowds of Chinese and foreign reporters; slick girls in summer frocks protecting their anonymity behind foreign sunglasses with the brand labels still attached to the lenses … And behind it all loomed the ever-present figure of Deng Xiaoping, China’s elder statesman, a symbol of reason and practicality, the realistic non-ideologue who even gave his blessing to the sale of Coca-Cola throughout the country. Overseas he allowed himself to be impressed by the munificence of a Tokyo supermarket and the pre-fab miracle of Japan. He traveled to America and donned a ten-gallon cowboy hat in Texas; and, finally, he gave the nod of approval to America’s king of Cold War comedy, Bob Hope, to wow Chinese audiences. In a guilt-ridden gesture of recognition, so typically American, Time magazine, the long-time champion of Taiwan, made Deng ‘Man of the Year’. You could almost hear Henry Luce turning over in his grave. China was entering a period of rapid change and many observers in the West were only too willing to believe that she wanted to be like us.

There is little question that Deng has deftly manoeuvred China away from its xenophobic, narrow and stagnant past; that he has done so with a minimum of bloodshed and with such a reassuring veneer of moderation, has possibly earned him a special place in the history of twentieth century politics. It has definitely won from him a unique position in the annals of the tangled and gory history of China. For a politician of a communist state he has been uncharacteristically discreet. Even now that he is the ultimate administrative and ideological guiding force in China he sees no need to emulate the cocky Khrushchevs and bovine Brezhnevs of the Soviet Union, pointedly foregoing all claims to lofty titles and public accolades. Be that as it may, for informed Western opinion to continue to regard Deng as a solitary voice of reason in the wilderness of Chinese newspeak, or as a capitalist in Chairman’s clothing, is surely no less a conceit than to conclude that a former head of the KGB was a closet Westernophile just because he liked listening to classical music and playing chess for relaxation.

***

***

The Film Everyone Talked About but No One Ever Saw

In early 1981, Deng Xiaoping took time out from overseeing his vast program of governmental and economic reform to put on the hat of film critic.

Over the Chinese New Year he had seen a film called Unrequited Love [苦戀]. It had just been passed by the Bureau of Cinema and was about to be publicly released. The Bureau had sent it over to the leader’s residence confident that it would provide him with a few hours of carefree holiday entertainment, and possibly earn the beleaguered film industry some much-needed praise. Their reaction to the Vice-Chairman’s suggestion that all copies of the film should be withdrawn from circulation was one of shock and disbelief. At a meeting with the political directors of the army some weeks later, Deng condemned the film in no uncertain terms and instructed the press to print a few articles criticizing the screenplay.

Unrequited Love was based on a scenario entitled The Sun and Man [太陽和人] by the army writer Bai Hua [白樺]. Bai had got the inspiration for his scenario from some interviews he had done with eccentric and multi-talented artist Huang Yongyu [黄永玉], who, by the way, visited Australia in 1981. Bai wrote a beefed up and highly dramatic version of the artist’s life during the Cultural Revolution. It was a wildly colourful exaggeration of reality for as Huang, like any other victim of political and artistic persecution will tell you, banality, not glamour and histrionics, is the trademark of evil. In the screenplay there is one poignant and explosive scene in which, after years of humiliation and anguish, the painter is given a chance to leave China. ‘But, I love my motherland!’ he protests to his daughter. ‘Sure,’ she replies bitterly, ‘but does your country love you?’

[Note: For more on Huang Yongyu, see Now What? — Greeting the Guimao Year of the Rabbit 癸卯兔年, China Heritage, 21 January 2023.]

Deng was scandalized – that a film of their own making could be openly preaching treason! ‘I’ve seen the film,’ he commented in a later speech.

I don’t care what the author’s motives were. At the end of it you’re left with one overriding impression: communism and socialism aren’t any good […] I’m told that the artistic level of the film is quite high, that makes it all the more poisonous. […] Just think of the effect the film would have if it were shown publicly. Some people say you can be patriotic without loving socialism; are you supposed to love an abstraction? […] I think the comrades involved on the ideological front should give a lot of thought to just why so many people support Unrequited Love.

As the army paper Liberation Daily dutifully damned the film, we in the West were told that the moderate Deng Xiaoping had consented to the campaign under pressure from the army!

In fact, for some years literary journals had been churning out brooding and sharp exposé literature about the Party and the society that made Bai Hua’s scenario look like a two-hour commercial for the Party. With their endless rounds of meetings and inspection tours Chinese leaders have little time for literature. As in the cave-dwelling years in Yan’an most of them still view cinema as their major cultural activity. Thus, as a result of Deng’s timely proscription, Unrequited Love was never released; however, the attention lavished on it by the media has made it the most famous film made in China since 1976.

One lesson writers and artists learnt from the ‘Bai Hua Incident’, as it became known, was that neither the government nor the literary establishment was eager to spark off another cultural purge. After a pro forma self-criticism Bai Hua was back at work, this time to produce an historical play that is a thinly-veiled attack on Mao’s dictatorship. The outspoken and fiery young poet, Ye Wenfu [叶文福], who had become a symbol of protest and conscience among the young, refused to admit his errors and has not been heard from since. So although 1981 acted as a warning to writers to tread more carefully, Bai Hua was living proof that the Cultural Revolution was truly over. Some writers concluded that they could continue to delve into the shadow territory of Modernism, the avant-garde and self-expression.

Just Another Thought?

And so it is that the tides of rightist bourgeois thought and ‘leftist’ economic and political backsliding have continued their ebb and flow in China over the last years. Even when his energies were devoted to the momentous questions of the moment Deng Xiaoping authorized and checked a volume of his own speeches and writing for publication. The Selected Writings of Deng Xiaoping appeared in bookstores throughout the country on 1 July this year, on the occasion of the sixty-second anniversary of the founding of the Communist Party. It was immediately hailed in the press as ‘a significant contemporary development of Mao Zedong Thought’, and it has been proclaimed as the guiding-light for China as the country moves into the fast-lane on the road to modernization.

The Selected Writings is by no means the first collection of Deng’s works. Some overly-zealous sycophants in Shenyang, north-east China, had produced a sample issue of a book with the unoriginal title, Quotations of Deng Xiaoping. Those concerned were sternly reprimanded for their temerity: How dare they attempt to vulgarize the spirit of Comrade Xiaoping’s policies? Truly, there is no greater mistake than doing the right thing at the wrong time.

Gone are the shiny red plastic covers of Mao’s Selected Works with their embossed gold titles; Deng’s unpretentious volume has a sedate pale lemon cover with black lettering. A casual reading of this work, as casual a reading as is possible of a dry collection of policy speeches ranging from suggested guide-lines for a retirement scheme for the revolutionary gerontocracy to an opening address made to the Twelfth National Congress of the Communist Party of China, reveals none of the pithy philosophizing or literary panache of Mao Zedong. Although he may be lacking in flair, Deng presents a set of coherent ideas that over the next years will nurture an ideologically sound and politically trustworthy generation of hard-headed technocrats whose task is to create a uniquely Chinese and modern socialist state.

It is in the breadth of vision and daring of his policy initiatives, especially in the field of economics, that Deng shows himself to be no less a revolutionary or social experimenter than Mao. He more than any other individual has set China on a course between the poverty socialism of the Eastern Bloc and the uninhibited capitalism of the West. How things will develop after his death no one can say for sure. In the meantime, Deng has obtained a consensus in the Central Committee to clean out the Party of anything up to a third of its thirty million members so as to ensure that the chilling prophecy of Wang Hongwen [王洪文], the fourth and youngest member of the Gang of Four, does not come true. In 1975, Wang had sneered at Deng’s attempts to rationalize government policy with the words, ‘We’ll know who the real winner is in ten years time.’

The prelude to the purge of the Party is the present operation to do away with ‘spiritual pollution’. The solid little compendium of Deng’s writings may be as diminutive in size as its author, but over the last few months it has become holy writ for every citizen of the People’s Republic, and it is one’s understanding and acceptance of its contents that determines whether one has achieved true ‘oneness with the government’.

It is interesting to note that the years 1975-1982 are clearly printed in brackets under the title of The Selected Writings of Deng Xiaoping. This is presumably a sign that we can expect future updates of the Vice-Chairman’s immutable remarks.

Making the Crime Fit the Punishment

Just as his book was heading for the top of the 1983 best-seller lists in mid-summer, Deng took a holiday on the beach at Beidaihe, a resort near Tianjin. It is widely rumoured that after a much publicised swim à la Mao, pictures of which even appeared in the Australian press, his car was ambushed by a gang of young rowdies. It does not take much imagination to picture the expressions of horror on the faces of these knife-toting toughs when they discovered just who it was they were trying to mug; equally, their fate leaves little room for speculation. Similar flagrant breeches of the law affecting and even endangering important public figures had occurred before, and at the time the notorious Wang brothers were still on the loose.

Wang Zongfang [王宗方] and Wang Zongwei [王宗瑋] had begun their orgy of crime and violence in the north-east of China in February. The younger of the two, Zongwei (26), had been trained as a sharp-shooter in the PLA, and when he and his brother were arrested for theft, he managed to get hold of a police gun and wipe out an entire police station with a few well-aimed shots. It was in this same month, after an alarming increase in violent crime over the last year and a half, that Peng Zhen [彭真], China’s law-maker, had authorised a law and order campaign. Even then, a mere two months later in May a small group of corrupt cadres, a member of China’s ‘mafia’ and a model worker hijacked a passenger plane and flew it to South Korea, facilitated in their efforts by the bumbling police authorities, much to the embarrassment of the government. The Wangs continued to travel the land with seeming impunity.

Rewards of unprecedented sums of money for information leading to their capture or assistance in their arrest were offered in May. Despite a flurry of internal documents on the subject and an increased police presence in the city streets, the Wangs continued their flight south, killing everyone who questioned them or even looked at them suspiciously. Such were the rumours of their marksmanship and brutality that they were able to continue their bloody rampage for another four months, even causing a major alert in Beijing and a mood of mass hysteria in early June when someone said they had spotted them at the train station. Although they were finally tracked down and shot while resisting arrest in Jiangxi Province, South China in September, government leaders were infuriated by the disgraceful inefficiency of the police. The Wangs had managed to kill over thirty people during their seven months on the run.

But to Deng and his fellows these incidents and the epidemic of crime that was sweeping the country indicated something more basic and dangerous than mere police inefficiency and corruption. Incorrect thinking, a decay of Party morals and a suffocating spiritual pollution were threatening the very foundation of the State.

***

Back in 1982 numerous cases of high level corruption and ‘economic malfeasance’ had been uncovered and the offenders brought to trial, but if anything the situation has continued to deteriorate. Corruption, violence, theft, and all manner of unacceptable social behaviour are not viewed in China as inevitable social ills, but rather as a reflection of an incorrect world view, the externalization of a bourgeois mentality. Thus, while the Cultural Revolution and the anarchy lauded by Jiang Qing [江青]and her cronies are again being condemned for having set off this chain-reaction of disorder, the real culprit of China’s present ills has been positively identified as the West and her impure ways.

In August the Party ordered a massive law and order campaign that would make a decisive strike against crime throughout the country, and lay the basis for an ideological mopping up program later. The new Penal Code that had only been in force since January 1980 stipulated that criminal offenders can be sentenced to anything from three to seven years in gaol, while the most severe punishment for murderers is life imprisonment. So as to be able to deal with the exigencies of the law campaign, the Penal Code was hurriedly revised by the National People’s Congress in September, allowing the death penalty to be passed on serious criminal offenders of all types. That these post-haste revisions were made over a month after the law campaign had begun, and presumably after a considerable number of executions had already been carried out, seems to have given rise to no public outcry in China.

There is little doubt that the safety and well-being of the average citizen was gravely threatened by the mounting crime wave, and that the majority of Chinese welcomed the speedy and stern punishments meted out to criminals. However, the Chinese government’s continued predilection for the use of Blitzkrieg methods when dealing with social ills, a ‘campaign mentality’ that reveals the lack of any real system and little understanding of the concept of legality in the need for crime-prevention, continues to encourage long periods of neglect and slackness that are interspersed with spurts of uncompromising law enforcement. I daresay the draconian nature of punishments is a contributing factor in the increasingly bloody nature of even minor crimes. The exiling of hundreds of thousands of youths pronounced guilty of forming gangs and engaging in petty crime to the outlying provinces of Qinghai and Xinjiang, and the unofficial figure of over 5,000 executions in a two-month period leaves the observer with few illusions about the nature of China’s new ‘rule of law’.

***

***

Public Pollutant No. 1

During his tussle with the extreme Maoist ideologues following the Cultural Revolution, Deng Xiaoping gradually positioned a group of new and innovative theoreticians and propagandists in key media jobs. These men served the vital need to provide China’s new leaders with ideological medicine potent enough to cure the country of her post-1957 Maoist ills, as well as prescribing a method for the Party to reassess its calamitous recent history and justify its present heterodoxy. Two of the most outstanding members of this doctrinal think-tank were Hu Jiwei [胡績偉] and Wang Ruoshui [王若水]. Until October they were the directing force behind the People’s Daily, the main news organ of the Communist Party and the most influential newspaper in China.

Wang Ruoshui was very outspoken for his tender years – a middle-aged man he is little more than a callow youth in Chinese terms. He was the first Party ideologist to offer a coherent analysis of the rule of Mao Zedong and the feudal nature of his personality cult. In recent years he has concentrated on a study of Marx’s early theories of the ‘alienation of labour’ and the prickly question of humanism. Up to November free-wheeling academic discussion and artistic debate were still the order of the day, and it was in this atmosphere of ‘letting a hundred flowers blossom and a hundred schools of thought contend’ that Wang and a number of others probed into the more sensitive areas of Marxist theory.

The Cultural Revolution had left a generation of China’s young doubting and questioning the basic tenets of socialism. Some found hope and solace in the writings of Dai Houying [戴厚英], the author of a startling novel about middle-age, a work that she uses to rediscover and determine a sense of her own humanity. Or in reading the short story writer Liu Xinwu [劉心武], who until just last year was the darling of the literary establishment. Things turned sour when he published a quirky story entitled The Black Wall in which he describes a man who paints his section of a courtyard house in Beijing completely black on the spur of the moment. Naturally, his strait-laced neighbours are scandalised; and Liu has been censured for using his popularity as a writer to extol the virtues of anti-social individualism and eccentricity.

While these and similar works made a cautious debut on the literary scene, a small number of Marxist thinkers like Wang had been making an exacting study of Marx’s writings to affirm the absolute value of the individual and the importance of individual expression in society. And, for the writers who had been edging towards a literary view in favour of artistic excellence, individual expression and intellectual honesty, it was these new ideas, couched as they were in acceptable Marxist terminology that held promise for a way out of the intellectual stagnation of the past decades towards a truly contemporary Chinese culture. It was in providing those in academe and the arts with a well-argued Marxist excuse for pursuing individual and innovative interests that Wang first fell foul of his superiors.

To talk about the unique value of the individual and ‘abstract humanity’ was bad enough, but when Wang turned his considerable intellectual powers to the study of the concept of ‘socialist alienation’ all hell broke loose. The tumescent disagreements over Marxist theory finally grew to the point of explosion on the occasion of the centenary of Marx’s death last March. Zhou Yang [周揚], the grand old man of the Chinese cultural bureaucracy – who is still known in the West by his Cultural Revolution epithet ‘the Cultural Tsar’ [文化沙皇] – chose this day to give a speech on the subject. The core message of Zhou’s address was that socialist societies also create an ‘alienation of labour’ resulting in popular disaffection from the system and certain incurable social ills. In so many words Zhou had declared that after a lifetime as a Marxist – he is now 75 – he had come to the conclusion that socialist society, like its theoretical opposite capitalist society, is fatally flawed. This theory goes a long way in identifying the reasons for China’s massive social problems – ideological dissolution, Party corruption, continued political instability, widespread disillusionment, the increased crime rate, and so forth – in fact, it goes just too far. To Party leaders Zhou’s words brought back the specters of 1957 when Chinese intellectuals had called for a limitation of Party power in the wake of the ‘Prague Spring’, as well as the uneasy spirits of the ‘Beijing Spring’ of 1979 with its demand for greater democracy.

This was nothing less than a frontal assault on the underlying principles of the State. And the backbone of the speech turned out to have been written not by the ailing Zhou Yang, but by a leading Party propagandist and theoretician, Wang Ruoshui.

In early November both Wang and his superior, Hu Jiwei [胡绩伟], were dismissed from their sensitive posts in the People’s Daily. True, they were not purged – no struggle meetings or gaol, nor have they been sent to work on a state farm as would have been the norm in the past. It is certainly a sign of the enlightened and rational atmosphere that prevails in China at the moment – an atmosphere, I hasten to add, that has in no small part resulted from a political ennui after twenty years of empty-headed fanaticism – that both of these men have been given ‘promotional chastisement’: they’ve been kicked upstairs. However, no matter how laudable this present method of using ‘calm winds and fine rains’ [和风细雨], as the poetic turn of Chinese political cliché puts it, for any creative thinker or writer worth his salt, is not a ban or caveat on his work a source of spiritual and intellectual anguish no less scarifying than actual physical punishment?

For his troubles Zhou Yang, whose Cultural Revolution self-criticisms and denunciations are weighed by the kilo, has been obliged to make a public self-denunciation in which he thanks Deng Xiaoping and Chen Yun [陈云] for their timely attack on spiritual pollution and asks for forgiveness from the people. In his hollow mea culpa Zhou acknowledges that

it was neither prudent nor sufficiently humble of me to raise the question [of alienation] in such a precipitate manner on that particular occasion. It was also quite unsuitable for me to stubbornly hold to my views even after some of the comrades in charge of theoretical and propaganda work voiced their objections. […] I did not pay enough attention to making a clear distinction between [my own] ideological view and the bourgeois concept of ‘alienation’, with the result that my comments may be distorted and used by people who are ideologically or emotionally opposed to socialism for their own ends. [My comments] may have also shaken the faith of some feeble-minded individuals in socialism, or led them to lose hope in the future of communism …

I would venture a guess that Zhou, like Wang, Hu Jiwei and many, many others, is presently making a salutary study of The Selected Writings of Deng Xiaoping.

China’s First ‘Non-Movement’

In early October a plenary meeting of the Communist Party initiated a process of Party rectification aimed at ousting undesirable elements. But before this massive ‘house-cleaning’ could begin, decisive steps had to be taken to clear the cultural and intellectual air of ‘spiritual pollution’.

Spiritual what? – people in China were nearly as dumbfounded by this curious new expression as we are in the West. But in his speech at the plenum Deng Xiaoping summed up the concept in no uncertain terms:

Spiritual pollution means the dissemination of any and every type of degenerate and moribund thinking that belongs to the bourgeoisie and other exploiting classes. It is anything that encourages a lack of confidence in our socialist cause or in the leadership of the Communist Party.

When Hu Yaobang [胡耀邦], Secretary of the CPC, was grilled by a host of reporters during a state visit to Japan at the end of November, he was just as sweeping in his definition of the ‘spiritual pollution’ they want to clean up. ‘We want to eliminate the incorrect words and deeds which threaten our modernization program, especially those words and deeds that endanger our young people…’ Both Chinese leaders and the media have been at pains to point out that ‘this is not another movement’. We are repeatedly told that ‘Economic policies and the open policy to the West will not be affected,’ so that the filthy-rich international bourgeoisie do not get jumpy about their investments in China. I suspect the economic scene in China will continue to develop, basically untrammeled by these annoying ideological considerations. As to just what effect all of this is to have on the country’s shell-shocked intellectual and cultural life remains to be seen.

‘This is not another movement!’ No struggle sessions, no persecutions, no labour reform for thought-criminals. No, it is nothing like the two decades of pitiless campaigns that devastated the best minds of the most populous nation in the world and frittered away the energies of countless millions. Nevertheless, over the last eight weeks the Chinese media and Party organization, which together touch on every aspect of life in China, have been engaged in very definite propaganda warfare. The ideological and organizational ‘house-cleaning’ has just begun. Already there have been sackings, demotions, self-criticisms, the compilation of lists of films, plays and literature that are to be banned, restrictions on academic and artistic debate with writers attacking the works of other writers, and intellectuals denouncing the ideas of other intellectuals. And, above all, the Chinese are once more being enjoined to study the political thought of one man and to make themselves body and soul ‘at one with the policies of the Central Committee of the Communist Party’. No, perhaps this is not another one of those movements, this time it could just possibly be a grand success.

Most people seem to agree that things were getting out of hand. All the beguiling influences of Western thought; the alarming heresies of ‘abstract individualism’ and ‘alienation’. If left unchecked who knows where it would all end? As Zhou Yuanbing [周原冰], an outstanding Chinese expert on ethics recently pointed out,

The value of any individual is determined by society, and furthermore by the actual needs of that society. If you do not make any contribution to your society or are harmful to it, then you have no value, or may be said to be nothing more than a ‘negative’. If the notion of abstract humanity is encouraged there will be no end of strife. Why, people will start saying: workers have an intrinsic value, as do university students and cadres. This will lead to people arguing that it is inhuman to send people to work in the border regions, that to do so shows a disregard for the value of the individual. It is precisely thinking like this that has been poisoning the minds of the masses, turning them into selfish individualists. Such thinking is detrimental to our socialist cause, and will do nothing but harm to the (correct) development of one’s self.

—Guangming Daily 光明日報, 5 November 1983.

However, it may well be that I have given too much credence to the orchestrated ‘public opinion’ that fills the Chinese press these days. It is hard to imagine that a cleaning up of ‘spiritual pollution’ through a concerted propaganda effort and administrative restrictions, be it over a period of three months or even three years, will have much efficacy. For China is a country where thirty years of saturation propaganda denouncing bourgeois thinking and lifestyles, political study piled on mass movements, has completely failed to raise the average citizen’s awareness of the dangers of crass, popular commercialized culture. That a number of China’s writers and intellectuals have come to embrace their past ideological foes with enthusiasm is a phenomenon of considerable significance, and one that must be deeply disturbing for the country’s leaders.

A major source of Deng and his Party’s troubles is to be found in the very economic policies of which they are so proud. For in allowing a limited mixed economy – individual farming, small businesses and a gamut of private ‘entrepreneurs’ – the government has opened the Pandora’s Box of market forces. Consumerism; the raising of the standard of living; individual wealth; the desire to keep up with the Wangs next door – all of these are not only allowed but actively encouraged in the media. The government now recognizes and even acts to increase economic, educational and social inequalities – ‘Let one group prosper first’ is the slogan. There is no doubt that these policies have been warmly welcomed by the vast majority of Chinese; and even in the short period of their implementation they have wrought astounding changes throughout the country. However, even if one looks at all of this wearing Marxist blinkers, it appears as if these policies have liberated and now reinforce the rabid ‘small production’ mentality of the Chinese peasantry, as well as emboldening the petit-bourgeois man hidden deep in the Id of every urban dweller. To fling the doors of economics wide open and still expect to retain control of the people’s minds by using methods from the 1950s is the essential paradox of contemporary China, and the dilemma of her leaders. The Communist Party sees its main enemy in Western influences, heedless, for the moment, that China’s economic cure may well be the root-cause of her ideological disease.

The Last Word

Yet speculation is rife among ‘China watchers’ that Deng Xiaoping, the pragmatic moderate, is again under pressure from hard-liners in the army to carry out an ideological campaign. What better way to further confound these quizzical observers than by ending with a few words from the Vice-Chairman himself:

Won’t some people probably say that this is another ‘crackdown’? But in regard to such matters (dissent, opposition to the Party, bourgeois tendencies, etc.) we have never ‘let up’, so there’s no question of this being a ‘crackdown’.

— Deng Xiaoping, The Present Situation and Our Duties

(16 January 1980), Selected Writings, p.213

November, 1983

Murrumbateman, NSW

Australia

- Original Note to Readers: For those readers not up to date with New Wave bourgeois culture, the title of this article may require a word of explanation. ‘Culture Club’ is a British group that achieved international success during 1983. The lead singer, Boy George, bedecks himself with braids and ribbons, and it is his image of sexual ambivalence that seems best to sum up the yin-yang flip-flops of Chinese culture in the 1980s.

- Update: Culture Club reformed in 2014 and in December 2020 preformed a ‘Rainbow in the Dark’ a benefit concert live-streamed internationally organised in response to the Covid pandemic. The concert featured new ballad version of their old hit ‘Karma Chameleon’.

In November 2022, Boy George appeared as a contestant in the twenty-second UK series of I’m a Celebrity…Get Me Out of Here!. He was outspoken about his distaste for fellow contestant Matt Hancock, a former government health secretary known for his dereliction of duty during the Covid crisis in 2020. George was eliminated from the show on 22 November 2022. Hancock lasted the course to finish in third place.

***

Source:

- Geremie Barmé, ‘China Blames the West for “Cultural Pollution” ’, The National Times, 13-19 January 1984

***

Further Reading

- David Kelly, translator and editor, ‘Writings of Wang Ruoshui on Philosophy, Humanism and Alienation’, Chinese Studies in Philosophy: 16 (3), Spring 1985: 1-120

- ‘Humanity!’, in Geremie Barmé and John Minford, eds, Seeds of Fire: Chinese Voices of Conscience, Hong Kong: Far Eastern Economic Review, 1986, pp.149-166

- David Kelly, ‘The Emergence of Socialist Humanism in China: Wang Ruoshui and the Critique of Socialist Alienation,’ in Merle Goldman, Timothy Cheek and Carol Lee Hamrin, eds, China’s Intellectuals and the State, Harvard University Press, 1987, pp.159-182

- 王若水, 人道主義在中國的命運和「清污」運動, 1992

- Børge Bakken, The Exemplary Society — Human Improvement, Social Control, and the Dangers of Modernity in China, Oxford University Press, 2000

- Michael Dutton, Policing Chinese Politics, A History, Duke University Press, 2005

- Cui Weiping 崔衛平, Why Does the Spring Breeze Not Warm the Earth? The 1980s Debate on Humanism in China 為什麼沒有春風吹拂大地?中國八十年代人道主義論戰, introduced and translated by Selena Orly and David Ownby

- 張顯揚,王若水在人道主義與異化問題爭論中,《炎黄春秋》, 2008年第5期

- Susan Trevaskes, Policing Serious Crime in China: From ‘strike hard’ to ‘kill fewer’, London and New York: Routledge, 2010

- Kevin Carrico, ‘Eliminating Spiritual Pollution: A Genealogy of Closed Political Thought in China’s Era of Opening’, The China Journal 78 (1), 2017: 100-119

- Gloria Davies, Discursive Heat: Humanism in 1980s China, China Heritage, 30 July 2018

- Julian Gewirtz, Never Turn Back: China and the Forbidden History of the 1980s, Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2022, chapter 2

In Xi Jinping’s Empire of Tedium:

- Prelude to a Restoration: Xi Jinping, Deng Xiaoping, Chen Yun & the Spectre of Mao Zedong, China Heritage, 20 September 2021

- Introduction 瞽 — You Should Look Back, 1 February 2022

- Appendix XXXI 人礦 — Xi Jinping’s Harvest — from reaping Garlic Chives to exploiting Huminerals, 6 January 2023; and,

- Annexure, Xi Jinping’s Harvest — an anthem for China’s disaffected Huminerals, 7 January 2023

***

Hu Muying’s Warning

November 2014

(Hu is Hu Qiaomu’s Daughter)

[Note: see also 梨園卉, 胡木英:教育陣地的丟失不是一日之寒, 今日頭條; and, ‘The Children of Yan’an’ in Chapter Twenty-eight, Part I, 赤字 — 華表 huabiao — Red Rising, Red Eclipse, 29 December 2022.]